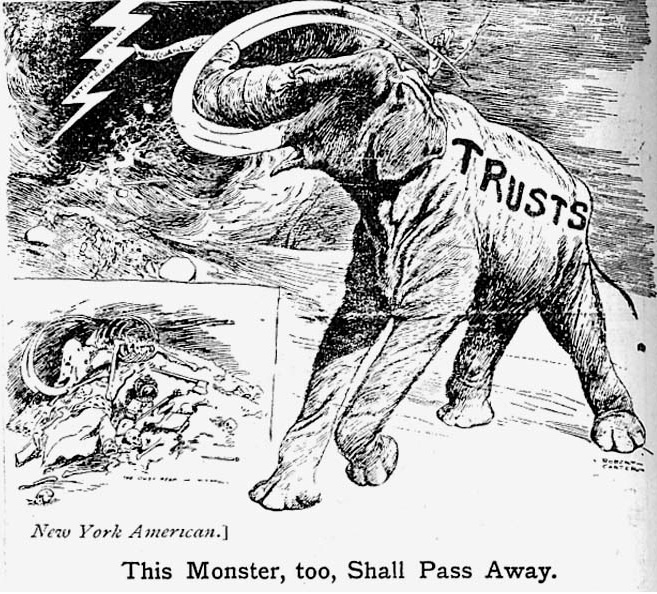

TicketNetwork, an online ticket marketplace, sued CEATS, a non-practicing IP company, for declarations that Ticket’s business did not violate CEATS’s patents or a related license agreement.

TicketNetwork, an online ticket marketplace, sued CEATS, a non-practicing IP company, for declarations that Ticket’s business did not violate CEATS’s patents or a related license agreement.

CEATS won at trial, and while its claim for attorneys fees was pending, obtained an order allowing it to see a list of Ticket’s website affiliates. That order restricted access to certain designated in-house representatives.

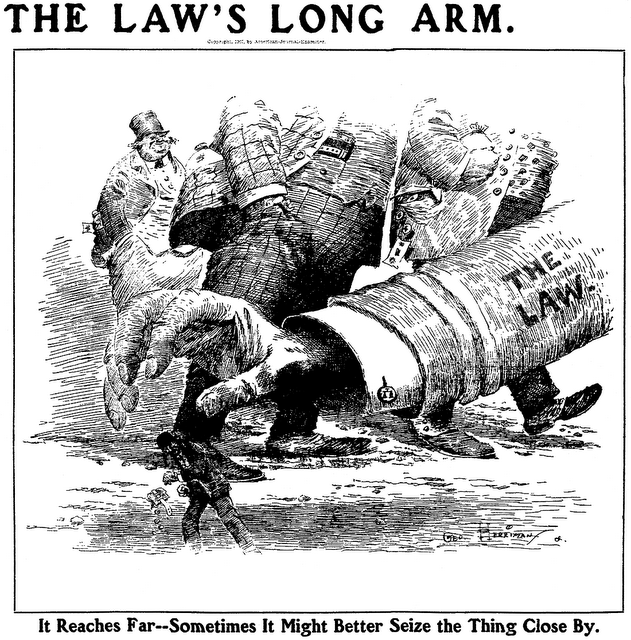

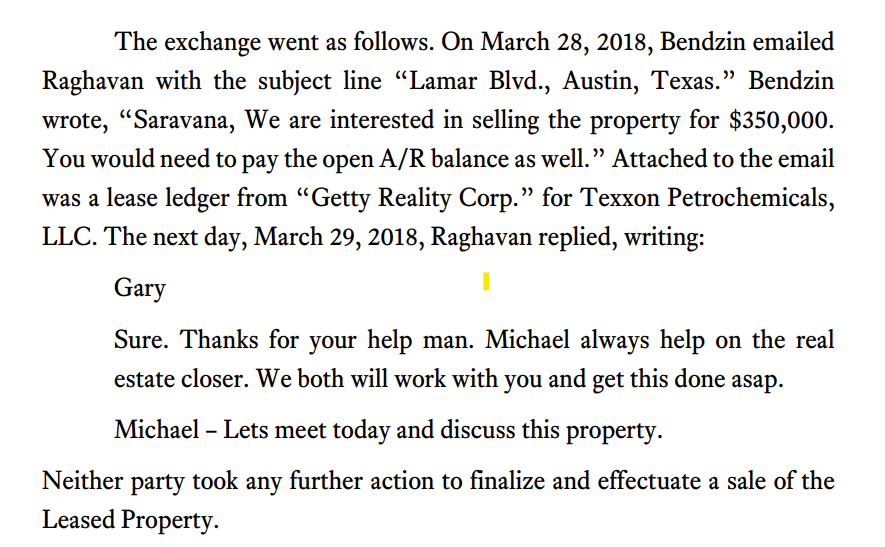

CEATS’s CEO, who was not supposed to see the list, then sent Ticket’s CEO a settlement demand–attaching the list. After significant proceedings, the district court awarded (1) a 30-month injunction against any dealings with the companies on the list and (2) $500,000 against CEATS, its CEO, and two litigation consultants.

The Fifth Circuit, inter alia:

- Vacated the award against the individuals: “The Individuals did not receive notice that monetary sanctions were pending against them, and they did not receive a pre-deprivation opportunity to defend themselves at a hearing. By the time the district court heard their response, it had already decided against them. That was an abuse of discretion.”

- Vacated the injunction: “We also agree with CEATS that the district court did not make the bad-faith finding that is a prerequisite to litigation-ending sanctions under [Fed. R. Civ. P.] 37(b). Instead, the district court found that CEATS acted recklessly, and then it equated recklessness with bad faith. We have rejected that equivalence.”

- Vacated the fee award: “[T]here was a significant disparity between the rates that the first court approved when it awarded attorney fees to CEATS (at an earlier stage of litigation) versus the rates that it approved when it awarded attorney fees to Ticket (as part of the sanction against CEATS).”

CEATS, Inc. v. TicketNetwork, Inc., No. 21-40705 (June 19, 2023). The Court aptly summarized: “We AFFIRM in (small) part, VACATE in (large) part, and REMAND for further proceedings.”