The Fifth Circuit’s unfortunate Erie guess in Priester v. JPMorgan Chase Bank, 708 F.3d 667 (5th Cir. 2013), about limitations for an action to quiet title on a home-equity lien, was later rejected by the Texas Supreme Court in Wood v. HSBC Bank USA, 505 S.W.3d 542 (Tex. 2016). Meanwhile, the Priesters’ problems with their lender continued. The Fifth Circuit declined to consider their motion for reconsideration under Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b), noting a lengthy delay by the Priesters in bringing the motion, and observing: “If a ‘change in law’ automatically allowed the reopening of federal cases, then anytime the Supreme Court resolved a circuit split, the courts that had taken the view that did not prevail would have to reopen cases no matter how long ago the judgments issued. . . . [The Priesters] are worried that the earlier federal judgment against them may pose a res judicata problem. But res judicata is the ordinary result of a final judgment, not an extraordinary circumstance warranting relief from one.” Priester v. JP Morgan Chase, No. 18-40127 (re-released as published on July 1, 2019).

The Fifth Circuit’s unfortunate Erie guess in Priester v. JPMorgan Chase Bank, 708 F.3d 667 (5th Cir. 2013), about limitations for an action to quiet title on a home-equity lien, was later rejected by the Texas Supreme Court in Wood v. HSBC Bank USA, 505 S.W.3d 542 (Tex. 2016). Meanwhile, the Priesters’ problems with their lender continued. The Fifth Circuit declined to consider their motion for reconsideration under Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b), noting a lengthy delay by the Priesters in bringing the motion, and observing: “If a ‘change in law’ automatically allowed the reopening of federal cases, then anytime the Supreme Court resolved a circuit split, the courts that had taken the view that did not prevail would have to reopen cases no matter how long ago the judgments issued. . . . [The Priesters] are worried that the earlier federal judgment against them may pose a res judicata problem. But res judicata is the ordinary result of a final judgment, not an extraordinary circumstance warranting relief from one.” Priester v. JP Morgan Chase, No. 18-40127 (re-released as published on July 1, 2019).

Monthly Archives: June 2019

The federal system’s more-forgiving approach, to what Texas state practice calls “the Casteel problem,” was on display in Young v. Board of Supervisors of Humphreys County, Mississippi. After a jury trial, Young won a judgment under § 1983 for depriving him of the use of several properties. Among other appeal points, “The Board takes issue with Jury Instruction 4, which told the jury that it could find the Board liable if it found, by a preponderance of the evidence, one of three things: (1) ‘The Board of Supervisors authorized a violation of Mr. Young’s property rights,’ (2) ‘Dickie Stevens had been given the authority by the Board to take the action he took with respect to Mr. Young’s property,’ or (3) ‘The Board ratified Dickie Stevens’ actions after the fact.'” The Fifth Circuit held that as to the second theory, “[e]ven assuming that the court erred in allowing the jury to determine whether Stevens was a policymaker, there was legally sufficient evidence for a reasonable jury to hold the Board liable on a ratification [the third] theory . . . Thus, ‘any injury resulting from the erroneous instruction is

The federal system’s more-forgiving approach, to what Texas state practice calls “the Casteel problem,” was on display in Young v. Board of Supervisors of Humphreys County, Mississippi. After a jury trial, Young won a judgment under § 1983 for depriving him of the use of several properties. Among other appeal points, “The Board takes issue with Jury Instruction 4, which told the jury that it could find the Board liable if it found, by a preponderance of the evidence, one of three things: (1) ‘The Board of Supervisors authorized a violation of Mr. Young’s property rights,’ (2) ‘Dickie Stevens had been given the authority by the Board to take the action he took with respect to Mr. Young’s property,’ or (3) ‘The Board ratified Dickie Stevens’ actions after the fact.'” The Fifth Circuit held that as to the second theory, “[e]ven assuming that the court erred in allowing the jury to determine whether Stevens was a policymaker, there was legally sufficient evidence for a reasonable jury to hold the Board liable on a ratification [the third] theory . . . Thus, ‘any injury resulting from the erroneous instruction is

harmless.’“ No. 18-60618 (June 21, 2019).

Here is my PowerPoint from the recent appellate course sponsored by University of Texas CLE. I also discussed this month’s opinion in In re: City of Houston, granting mandamus relief in a privilege dispute.

Here is my PowerPoint from the recent appellate course sponsored by University of Texas CLE. I also discussed this month’s opinion in In re: City of Houston, granting mandamus relief in a privilege dispute.

In In re City of Houston, the Fifth Circuit succinctly held: “Having reviewed the submissions of the parties, the documents in dispute, which are contained in Exhibit A to the City’s motion to seal documents, and pertinent jurisprudence, we conclude that the electronic communications identified by the City in Tabs 3, 4, 5, 8 and 9 of Exhibit A fall within the attorney-client privilege and that mandamus relief is warranted with respect to such items. See In re: Itron, Inc.,883 F.3d 553, 567–69 (5th Cir. 2018); EEOC v. BDO USA L.L.P., 876 F.3d 690, 695-97 (5th Cir. 2017); Exxon Mobil Corp. v. Hill, 751 F.3d 379, 382–83 (5th Cir. 2014); In re: Avantel, S.A., 343 F.3d 311, 316–17 (5th Cir. 2003).” No. 19-20377 (June 18, 2019, unpublished).

In In re City of Houston, the Fifth Circuit succinctly held: “Having reviewed the submissions of the parties, the documents in dispute, which are contained in Exhibit A to the City’s motion to seal documents, and pertinent jurisprudence, we conclude that the electronic communications identified by the City in Tabs 3, 4, 5, 8 and 9 of Exhibit A fall within the attorney-client privilege and that mandamus relief is warranted with respect to such items. See In re: Itron, Inc.,883 F.3d 553, 567–69 (5th Cir. 2018); EEOC v. BDO USA L.L.P., 876 F.3d 690, 695-97 (5th Cir. 2017); Exxon Mobil Corp. v. Hill, 751 F.3d 379, 382–83 (5th Cir. 2014); In re: Avantel, S.A., 343 F.3d 311, 316–17 (5th Cir. 2003).” No. 19-20377 (June 18, 2019, unpublished).

In SEC v. Stanford Int’l Bank, Ltd., the Fifth Circuit reviewed an intricate, court-supervised settlement between the receiver for Stanford International Bank and several D&O carriers, and “conclude[d] the district court lacked authority to approve the Receiver’s settlement to the extent it (a) nullified the coinsureds’ claims to the policy proceeds without an alternative compensation scheme; (b) released claims the Estate did not possess; and (c) barred suits that could not result in judgments against proceeds of the Underwriters’ policies or other receivership assets.”

In SEC v. Stanford Int’l Bank, Ltd., the Fifth Circuit reviewed an intricate, court-supervised settlement between the receiver for Stanford International Bank and several D&O carriers, and “conclude[d] the district court lacked authority to approve the Receiver’s settlement to the extent it (a) nullified the coinsureds’ claims to the policy proceeds without an alternative compensation scheme; (b) released claims the Estate did not possess; and (c) barred suits that could not result in judgments against proceeds of the Underwriters’ policies or other receivership assets.”

The Court observed: “By ignoring the distinction between Appellants’ contractual and extracontractual claims against Underwriters, the district court erred legally and abused its discretion in approving the bar orders. These claims . . . lie directly against the Underwriters and do not involve proceeds from the insurance policies or other receivership assets. . . . [R]eceivership courts have no authority to dismiss claims that are unrelated to the receivership estate. That the district court was ‘looking only to the fairness of the settlement as between the debtor and the settling claimant [and ignoring third-party rights] contravenes a basic notion of fairness.'” No. 17-10663 (June 17, 2019).

The Northern District of Texas sent this message today: “The Earle Cabell Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse located at 1100 Commerce Street, Dallas, TX, will be closed to the public tomorrow [June 18]. Initial criminal proceedings that are scheduled tomorrow before a magistrate judge will be held at the Fort Worth division located at 501 W. 10th Street, Fort Worth, TX. Other proceedings scheduled for tomorrow in Dallas will be rescheduled unless you have been specifically informed of alternative arrangements by a courtroom deputy or other court personnel. Updates to this information will be provided on our website at www.txnd.uscourts.gov.”

After a 2011 amendment, the removal statute allowed a motion to remand based on diversity after a year if the “district court finds that the plaintiff has acted in bad faith in order to prevent a defendant from removing the action. 28 U.S.C. § 1441(c)(1). One of the removal-jurisdiction issues in Hoyt v. Lane Construction was the applicable legal standard to determine bad faith. The district court focused on the plaintiffs’ affidavits, which explained “why the Hoyts were reluctant to go to trial against Storm or accept Storm’s (apparently low) settlement offer,” but “do not explain why the Hoyts waited until just two days after the one-year deadline to dismiss Storm. On appeal, the plaintiffs argued for a standard based on equitable estoppel that had been developed in prior Fifth Circuit precedent, but the Court rejected those authorities as having been mooted by the 2011 amendment. No. 18-10289 (June 10, 2019).

After a 2011 amendment, the removal statute allowed a motion to remand based on diversity after a year if the “district court finds that the plaintiff has acted in bad faith in order to prevent a defendant from removing the action. 28 U.S.C. § 1441(c)(1). One of the removal-jurisdiction issues in Hoyt v. Lane Construction was the applicable legal standard to determine bad faith. The district court focused on the plaintiffs’ affidavits, which explained “why the Hoyts were reluctant to go to trial against Storm or accept Storm’s (apparently low) settlement offer,” but “do not explain why the Hoyts waited until just two days after the one-year deadline to dismiss Storm. On appeal, the plaintiffs argued for a standard based on equitable estoppel that had been developed in prior Fifth Circuit precedent, but the Court rejected those authorities as having been mooted by the 2011 amendment. No. 18-10289 (June 10, 2019).

Several parties entered an “Area of Mutual Interest” (AMI) agreement, a common feature of oil-and-gas development projects. The AMI included various interests “which were or are acquired after” the agreement’s effective date, “by a Party” to the agreement. But it excluded “all interests, leases or agreements owned by a Party prior to the Effective Date.” Thus, when a party bought interests from another party after the effective date, that sale was not within the scope of the AMI. The Fifth Circuit observed: “If Appellees sought to prohibit the type of activity in which EnerQuest engaged, they could have easily done so through the contract.” Glassell Non-Operated Interests, Ltd. v. EnerQuest Oil & Gas, LLC, No. 18-20125 (June 12, 2019).

Several parties entered an “Area of Mutual Interest” (AMI) agreement, a common feature of oil-and-gas development projects. The AMI included various interests “which were or are acquired after” the agreement’s effective date, “by a Party” to the agreement. But it excluded “all interests, leases or agreements owned by a Party prior to the Effective Date.” Thus, when a party bought interests from another party after the effective date, that sale was not within the scope of the AMI. The Fifth Circuit observed: “If Appellees sought to prohibit the type of activity in which EnerQuest engaged, they could have easily done so through the contract.” Glassell Non-Operated Interests, Ltd. v. EnerQuest Oil & Gas, LLC, No. 18-20125 (June 12, 2019).

Here is a copy of my PowerPoint from today’s presentation about business cases in the Dallas Court of Appeals during 2019. Thanks to all who came out, and to the DBA Appellate Section for the invitation!

Here is a copy of my PowerPoint from today’s presentation about business cases in the Dallas Court of Appeals during 2019. Thanks to all who came out, and to the DBA Appellate Section for the invitation!

With yesterday’s nomination of Hon. Sul Ozerden (right), who presently serves as a District Judge for the Southern District of Mississippi, the Fifth Circuit is on the cusp of having a full roster of active judges.

With yesterday’s nomination of Hon. Sul Ozerden (right), who presently serves as a District Judge for the Southern District of Mississippi, the Fifth Circuit is on the cusp of having a full roster of active judges.

Today’s post on 600Commerce hearkens back to a case covered by this blog several years ago when, literally, the ship had sailed. (The 600Commerce post goes on to note that a similar principle applies in a dispute about the right of possession (in Texas practice, a forcible detainer action), which becomes moot when “a writ of possession had been served on appellant” and thus “appellant is no longer in possession of [the] premises.” Jones v. Willems, No. 05-18-01191-CV (June 7, 2019). Longtime 600Camp readers will be interested to know that the ship in question, since reflagged as the M/V CALHOUN, is in Singapore as of the date of this post, still well away from Fifth Circuit jurisdiction.

Today’s post on 600Commerce hearkens back to a case covered by this blog several years ago when, literally, the ship had sailed. (The 600Commerce post goes on to note that a similar principle applies in a dispute about the right of possession (in Texas practice, a forcible detainer action), which becomes moot when “a writ of possession had been served on appellant” and thus “appellant is no longer in possession of [the] premises.” Jones v. Willems, No. 05-18-01191-CV (June 7, 2019). Longtime 600Camp readers will be interested to know that the ship in question, since reflagged as the M/V CALHOUN, is in Singapore as of the date of this post, still well away from Fifth Circuit jurisdiction.

AccentCare sent an arbitration agreement to Trammell’s home; “[t]he district court applied the ‘mailbox rule’ to presume that Trammell received the company’s proffered arbitration agreement even though she testified that she never received the contract and indicated to her employer that she was experiencing difficulties in receiving and sending mail.” This showing, especially given that AccentCare could not produce a signed agreement or otherwise rebut her claims about problems with mail, the Fifth Circuit reversed: “Because Trammell created a genuine issue of material fact regarding whether an arbitration agreement was formed, she is entitled to a jury trial under Section 4 of the FAA.” Trammell v. AccentCare, Inc., No 18-50872 (June 7, 2019, unpublished).

AccentCare sent an arbitration agreement to Trammell’s home; “[t]he district court applied the ‘mailbox rule’ to presume that Trammell received the company’s proffered arbitration agreement even though she testified that she never received the contract and indicated to her employer that she was experiencing difficulties in receiving and sending mail.” This showing, especially given that AccentCare could not produce a signed agreement or otherwise rebut her claims about problems with mail, the Fifth Circuit reversed: “Because Trammell created a genuine issue of material fact regarding whether an arbitration agreement was formed, she is entitled to a jury trial under Section 4 of the FAA.” Trammell v. AccentCare, Inc., No 18-50872 (June 7, 2019, unpublished).

(The specific FAA provision, often referred to but rarely used, says: “. . . the party alleged to be in default may, except in cases of admiralty, on or before the return day of the notice of application, demand a jury trial of such issue, and upon such demand the court shall make an order referring the issue or issues to a jury in the manner provided by the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, or may specially call a jury for that purpose”).

Rural electric cooperatives, created pursuant to the New Deal’s Rural Electrification Act, and that “‘act under’ and the [Rural Utilities Service]’s direction

Rural electric cooperatives, created pursuant to the New Deal’s Rural Electrification Act, and that “‘act under’ and the [Rural Utilities Service]’s direction

based on a close and detailed lending relationship and shared goal of furthering

affordable rural electricity,” sought to remove litigation about governance issues under the “federal officer” statute. The district court remanded but the Fifth Circuit reversed: “[I]t was error to conclude that the cooperatives have not presented a colorable federal defense, as required for federal officer removal jurisdiction. Again, this is not to say that the cooperatives will inevitably be successful in their preemption defense. Rather, our conclusion is a natural byproduct of the

fact that ‘one of the most important reasons for [federal officer] removal is to have the validity of the [federal defense] tried in a federal court.'” Butler v. Coast Elec. Power Assoc., No. 18-60365 (June 7, 2019).

Ekhlassi sued National Lloyds in Texas state court for a flood-insurance claim, arising out of a “Write Your Own” insurance policy issued in the carrier’s name but underwritten by the federal government. His filing may have satisfied the one-year statute of limitations for such a claim – the

Ekhlassi sued National Lloyds in Texas state court for a flood-insurance claim, arising out of a “Write Your Own” insurance policy issued in the carrier’s name but underwritten by the federal government. His filing may have satisfied the one-year statute of limitations for such a claim – the  parties disputed the trigger event – but his choice of a state forum proved fatal. The panel majority, applying Circuit precedent and authority from other Circuits, found that the grant of “original exclusive jurisdiction” in federal court by 28 U.S.C. § 4072 applied to his suit. A dissent argued that this statute, by its terms, applied only to a suit against FEMA’s Administrator and not a “WYO” carrier. Ekhlassi v. National Lloyds Ins. Co., No. 18-20228 (June 4, 2019).

parties disputed the trigger event – but his choice of a state forum proved fatal. The panel majority, applying Circuit precedent and authority from other Circuits, found that the grant of “original exclusive jurisdiction” in federal court by 28 U.S.C. § 4072 applied to his suit. A dissent argued that this statute, by its terms, applied only to a suit against FEMA’s Administrator and not a “WYO” carrier. Ekhlassi v. National Lloyds Ins. Co., No. 18-20228 (June 4, 2019).

District courts frequently “administratively close” an inactive matter, but that housekeeping measure does not create an appealable order: ‘”A ‘final decision’ generally is one which ends the litigation on the merits and leaves nothing for the court to do but execute the judgment.” In contrast, “a district court order staying and administratively closing a case lacks the finality of an outright dismissal or closure.” By administratively closing the case, the district court retains jurisdiction, meaning it can “reopen the case—either on its own or at the request of a party—at any time.” “[R]eservation of jurisdiction for the purpose of hearing substantive claims . . . precludes appellate jurisdiction because an order framed this way is not a final judgment.”’ Sentry Select Ins. Co. v. Ruiz, No. 18-50605 (May 23, 2019) (unpubl.)

District courts frequently “administratively close” an inactive matter, but that housekeeping measure does not create an appealable order: ‘”A ‘final decision’ generally is one which ends the litigation on the merits and leaves nothing for the court to do but execute the judgment.” In contrast, “a district court order staying and administratively closing a case lacks the finality of an outright dismissal or closure.” By administratively closing the case, the district court retains jurisdiction, meaning it can “reopen the case—either on its own or at the request of a party—at any time.” “[R]eservation of jurisdiction for the purpose of hearing substantive claims . . . precludes appellate jurisdiction because an order framed this way is not a final judgment.”’ Sentry Select Ins. Co. v. Ruiz, No. 18-50605 (May 23, 2019) (unpubl.)

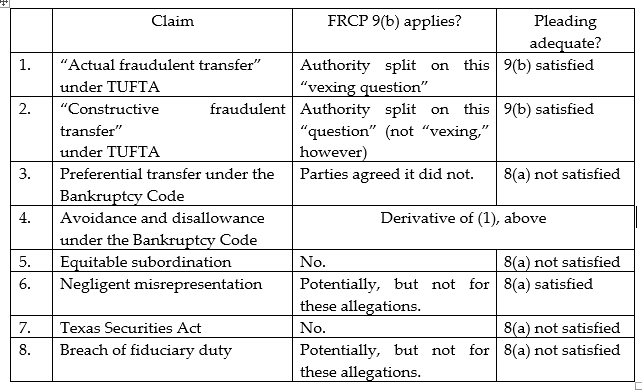

Life Partners’ Creditors’ Trust v. Cowley, No. 17-11477 (May 31, 2019), reviewed the dismissal of several highly-technical claims brought by a bankruptcy trustee about the sale of “viaticals” (investments in life insurance policies sold to third parties by the insureds). For each claim, the Fifth Circuit reviewed whether FRCP 9(b) or 8(a) applied, and then assessed the pleaded allegations, reaching these conclusions:

Sometimes, simply stating the issue gives a strong indication as to the answer. Such was the case in McGlothlin v. State Farm, which examined whether two Mississippi statutes were “repugnant” to one another (synonyms for “repugnant,” according to one online reference, include “abhorrent, revolting, repulsive, repellent, disgusting, offensive, objectionable, vile, foul, nasty, [and] loathsome . . . .” Specifically, Mississippi’s uninsured-motorist statute (1) required State Farm to pay the damages that an insured is “legally entitled to recover” from an uninsured driver, and (2) treats a fireman driving a fire truck as “uninsured,” as a result of the statute’s governmental-immunity statute. A driver who was rear-ended by a fire truck argued that these two statutes were “repugnant” and had to be read in favor of coverage; the Fifth Circuit disagreed: “The two sections’ being ‘confusing’ does not equate to repugnancy.” No. 18-60338 (May 31, 2019).

Sometimes, simply stating the issue gives a strong indication as to the answer. Such was the case in McGlothlin v. State Farm, which examined whether two Mississippi statutes were “repugnant” to one another (synonyms for “repugnant,” according to one online reference, include “abhorrent, revolting, repulsive, repellent, disgusting, offensive, objectionable, vile, foul, nasty, [and] loathsome . . . .” Specifically, Mississippi’s uninsured-motorist statute (1) required State Farm to pay the damages that an insured is “legally entitled to recover” from an uninsured driver, and (2) treats a fireman driving a fire truck as “uninsured,” as a result of the statute’s governmental-immunity statute. A driver who was rear-ended by a fire truck argued that these two statutes were “repugnant” and had to be read in favor of coverage; the Fifth Circuit disagreed: “The two sections’ being ‘confusing’ does not equate to repugnancy.” No. 18-60338 (May 31, 2019).