When not engaged in good-natured banter about typeface or proper spacing after periods, the appellate community often argues about the right place to put citations to authority. The traditional approach places them “inline,” along with the text of the legal argument. A contrarian viewpoint, primarily advanced by Bryan Garner, argues that citations should be placed in footnotes.

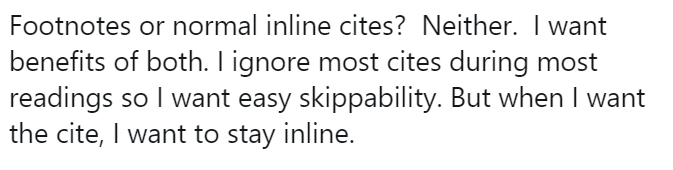

Has modern technology provided a third path? Professor Rory Ryan of Baylor Law School advocates “fadecites,” reasoning:

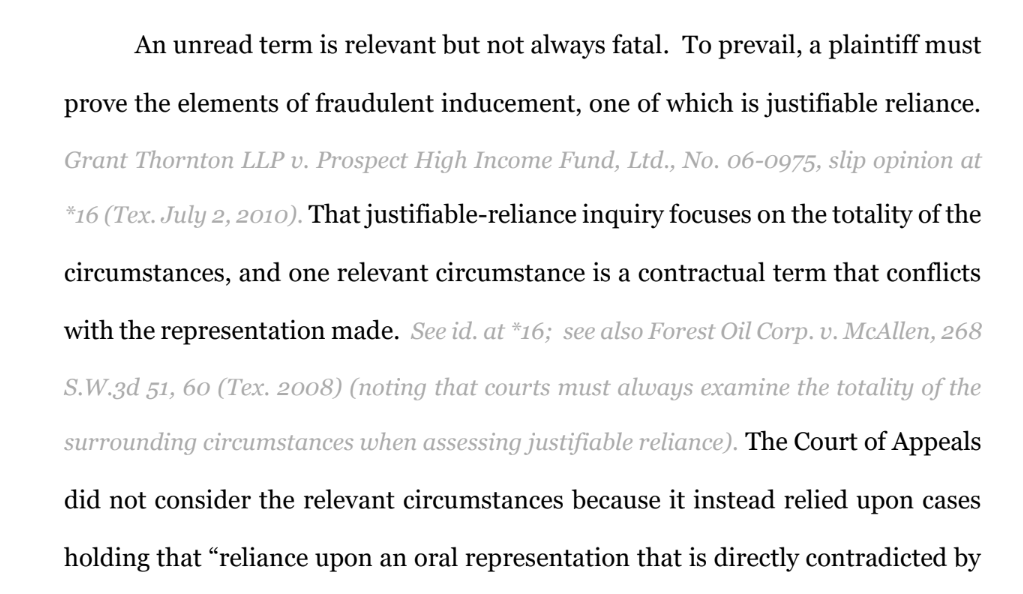

A brief using this approach would look like this on a first read:

(A longer example is available on Professor Ryan’s Google Drive.) The reader can quickly skim over citations while reviewing the legal argument. Additionally, assuming that the court’s technology allows it, case citations can be arranged to become more visible if the reader wants to know more information. Modern .pdf technology allows a citation to become darker and more visible if the reader places the cursor on it. A hyperlink to the cited authority could also be made available.

This idea offers an ingenious solution to a recurring challenge in writing good, accessible briefs. I’d be interested in your thoughts and Professor Ryan would be as well.