Beatriz Ball, L.L.C. v. Barballago Co., No. 21-30029 (July 12, 2022), a trade-dress case under the Lanham Act, produced a thorough concurrence by soon-to-depart Judge Costa about the distinctions between review of bench trials, and review of jury verdicts. He began by observing:

Beatriz Ball, L.L.C. v. Barballago Co., No. 21-30029 (July 12, 2022), a trade-dress case under the Lanham Act, produced a thorough concurrence by soon-to-depart Judge Costa about the distinctions between review of bench trials, and review of jury verdicts. He began by observing:

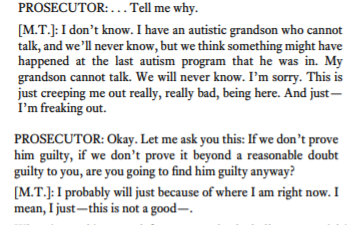

“I write separately to remark on how our remand of the trade dress claim reveals a paradox that has perplexed me about bench trials: We give a trial judge’s detailed and intensive factfinding less deference than a jury’s unexplained verdict.

If a jury had rejected Beatriz Ball’s trade dress claim—giving no more explanation than a simple ‘No’ on the verdict form—we would presumably affirm. After all, we do not hold that Beatriz Ball is entitled to judgment as a matter of law on this claim. Instead, we remand for the district court to reassess the trade dress claim because of some errors in its 33 pages explaining why it found no protectable trade dress.”

And he concluded after a review of history and social-science research: “It turns out, then, that there is good reason for the seeming anomaly of giving less deference to bench trials: Larger and more representative groups are the ones more likely to reach the correct outcome.”

In its analysis, the concurrence notes one commentator’s observation that “while the Seventh Amendment does not compel the backwards-seeming rule giving less deference to judges’ findings, it does explain it. ‘[O]ur traditional and constitutionalized reverence for jury trial’ is why we trust juries more.” An element of that “traditional reverence” may well include some indifference to whether a jury in fact reaches a “correct” result, as the mere existence of a jury has a powerful symbolic value in its own right. See generally Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 90 (1986) (“In view of the heterogeneous population of our Nation, public respect for our criminal justice system and the rule of law will be strengthened if we ensure that no citizen is disqualified from jury service because of his race.”).

In its analysis, the concurrence notes one commentator’s observation that “while the Seventh Amendment does not compel the backwards-seeming rule giving less deference to judges’ findings, it does explain it. ‘[O]ur traditional and constitutionalized reverence for jury trial’ is why we trust juries more.” An element of that “traditional reverence” may well include some indifference to whether a jury in fact reaches a “correct” result, as the mere existence of a jury has a powerful symbolic value in its own right. See generally Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 90 (1986) (“In view of the heterogeneous population of our Nation, public respect for our criminal justice system and the rule of law will be strengthened if we ensure that no citizen is disqualified from jury service because of his race.”).