Appellants argued that it a securities-registration exemption plainly applied to a transaction; the Fifth Circuit observed: “While the Gleasons now argue that section 4(a)(1)’s applicability is so obvious that the district court committed a clear error of law or manifest injustice, their able lawyers went in a different direction when opposing summary judgment,” and affirmed. Gleason v. Markel Am. Ins. Co, No. 18-40850 (July 30, 2019, unpublished).

Appellants argued that it a securities-registration exemption plainly applied to a transaction; the Fifth Circuit observed: “While the Gleasons now argue that section 4(a)(1)’s applicability is so obvious that the district court committed a clear error of law or manifest injustice, their able lawyers went in a different direction when opposing summary judgment,” and affirmed. Gleason v. Markel Am. Ins. Co, No. 18-40850 (July 30, 2019, unpublished).

Monthly Archives: July 2019

Two oft-addressed topics in 2019–the wreckage of Allen Stanford’s Ponzi scheme, and the appropriate deference to district court discretion in c omplex litigation– intersected in Zacarias v. Stanford Int’l Bank, No. 17-11703-CV (July 22, 2019).

omplex litigation– intersected in Zacarias v. Stanford Int’l Bank, No. 17-11703-CV (July 22, 2019).

The panel majority affirmed the “bar orders” entered by the district court in connection with a complicated settlement, observing: “The receiver initiated suit, negotiated, and settled with the Willis Defendants and BMB while empowered to offer global peace, that is, to deal with potential investor holdouts like the Plaintiffs-Objectors. These holdouts have been content for the receiver to pursue litigation for their benefit, then to participate as receivership claimants, collecting pro rata. Now, however, they ask to jump the queue, come what may to their fellow claimants who remain within the receivership distribution process.”

The dissent countered: “I share the majority’s appreciation for this settlement’s practical value. But in my view, the district court lacked jurisdiction to grant the bar orders. The Receiver only had standing to assert the Stanford entities’ claims. It could not release other parties’ claims, or have the court do so, in exchange for a payment to the Stanford estate. For better or worse, the objecting plaintiffs’ claims were beyond the district court’s power.”

“Ordinarily, courts must refrain from interfering with arbitration proceedings. But as our sister circuits have held, and as we now hold today, class arbitration is a ‘gateway’ issue that must be decided by courts, not arbitrators—absent clear and unmistakable language in the arbitration clause to the contrary.” 20/20 Communications, Inc. v. Crawford, No. 1810260 (July 22, 2019).

“Ordinarily, courts must refrain from interfering with arbitration proceedings. But as our sister circuits have held, and as we now hold today, class arbitration is a ‘gateway’ issue that must be decided by courts, not arbitrators—absent clear and unmistakable language in the arbitration clause to the contrary.” 20/20 Communications, Inc. v. Crawford, No. 1810260 (July 22, 2019).

An insurance company drew the Fifth Circuit’s ire (“Only an insurance company could come up with the policy interpretation advanced here”) in a dispute about coverage for a collision caused by drunk driving. The insurer argued “that drunk driving collisions are not ‘accidents,’ because the decision to drink (and then later drive) was intentional—even though there was admittedly no intent to collide with another vehicle. As Cincinnati points out, a jury found that Sanchez intentionally decided to drive while intoxicated, with ‘actual, subjective awareness’ of the ‘extreme degree of risk, considering the probability and magnitude of the potential harm to others.'” The Court found this argument inconsistent with the common meaning of the term “accident,” and further noted that under this reading of the policy: “[A] collision caused by texting while driving would also not be an accident. A collision caused by eating while driving would not be an accident. And a collision caused by doing makeup while driving would not be an accident.” Frederking v. Cincinnati Ins. Co., No. 18-50536 (July 2, 2019).

An insurance company drew the Fifth Circuit’s ire (“Only an insurance company could come up with the policy interpretation advanced here”) in a dispute about coverage for a collision caused by drunk driving. The insurer argued “that drunk driving collisions are not ‘accidents,’ because the decision to drink (and then later drive) was intentional—even though there was admittedly no intent to collide with another vehicle. As Cincinnati points out, a jury found that Sanchez intentionally decided to drive while intoxicated, with ‘actual, subjective awareness’ of the ‘extreme degree of risk, considering the probability and magnitude of the potential harm to others.'” The Court found this argument inconsistent with the common meaning of the term “accident,” and further noted that under this reading of the policy: “[A] collision caused by texting while driving would also not be an accident. A collision caused by eating while driving would not be an accident. And a collision caused by doing makeup while driving would not be an accident.” Frederking v. Cincinnati Ins. Co., No. 18-50536 (July 2, 2019).

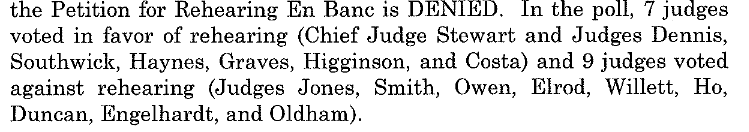

The Fifth Circuit denied en banc review of Inclusive Communities v. Lincoln Property Co., 920 F.3d 890 (5th Cir. 2019), which affirmed (over a dissent) the Rule 12 dismissal of Fair Housing Act claims against Dallas-area apartment businesses that declined to participate in the Section 8 program. The votes were as follows:

“Respect for the state system and the strictly circumscribed nature of federal jurisdiction requires our unflagging attention to these limits. We expect the same unflagging attention from litigants who invoke our jurisdiction.” Accordingly, the Fifth Circuit remanded the case of Midcap Media Finance LLC v. Pathway Data, Inc. for further review of diversity jurisdiction. “The parties in this case failed to properly allege diversity of ciizenship. First, the alleged only that Coulter was a California resident, not that he was a California citizen. Second, because MidCap is an LLC, the pleadings needed to identify MidCap’s members and allege their citizenship.” No. 18-50650 (July 9, 2019) (citations omitted).

“Respect for the state system and the strictly circumscribed nature of federal jurisdiction requires our unflagging attention to these limits. We expect the same unflagging attention from litigants who invoke our jurisdiction.” Accordingly, the Fifth Circuit remanded the case of Midcap Media Finance LLC v. Pathway Data, Inc. for further review of diversity jurisdiction. “The parties in this case failed to properly allege diversity of ciizenship. First, the alleged only that Coulter was a California resident, not that he was a California citizen. Second, because MidCap is an LLC, the pleadings needed to identify MidCap’s members and allege their citizenship.” No. 18-50650 (July 9, 2019) (citations omitted).

A concise case study in when a jury may evaluate contractual intent appears in Apache Corp. v. W&T Offshore, No. 7-20599 (July 16, 2019), in which the parties disputed how their Joint Operating Agreement about an offshore drilling project dealt with a $40 million charge associated with using a particular drilling rig.

A concise case study in when a jury may evaluate contractual intent appears in Apache Corp. v. W&T Offshore, No. 7-20599 (July 16, 2019), in which the parties disputed how their Joint Operating Agreement about an offshore drilling project dealt with a $40 million charge associated with using a particular drilling rig.

On the one hand, section 6.2 said that the operator “shall not make any single expenditure . . . costing $200,000 or more” unless an Authorization for Expenditure (“AFE”) is approved. A related provision, about accounting, says that an “acceptable reason[] for non-payment or short payment” includes the situation “when an AFE is not approved.” The defendant cited these provisions in declining to pay, arguing that it had not an AFE on the subject of the rig.

But the operator cited section 18.4, which addresses government-mandated plugging & abandonment operations, and said that the operator “[s]hall conduct” such activity as “required by a governmental authority,” with “the Costs, risks and net proceeds . . . shared by the Participating Parties in such well . . . .” It argued that the rig was necessary to carry  out such activity.

out such activity.

The Fifth Circuit agreed with the district court that “[a]pplying Section 6.2’s expenditure provision to a government-mandated P&A undertaken pursuant to Section 18.4 would lead to an absurd consequence: namely a situation is empowered to hold an operator hostage, preventing the operator from completing a legally required P&A, in order to extract a better bargain or avoid cost-sharing altogether.” Accordingly, whether section 6.2 applied to a section 18.4 undertaking “is ambiguous and was properly put to the jury.”

Tow v. Organo Gold Int’l presented a challenge, in a trade-secrets case, to a damages model based on “avoided costs” rather than “lost profits.” Specifically: “Weingust [Plaintiff’s expert] concluded that the distributor network was worth approximately $3.451 million based on the following two methodologies: the cost approach showed AmeriSciences had incurred about $6.2 million over five years to develop the distributor network, attract new distributors, and retain existing ones. The income approach considers how long income is expected from the asset and the amount of income each year. Weingust concluded the income approach dictated the network would generate $700,327 over ten years. Weingust testified that neither valuation method was better than the other, so he averaged the two to conclude the value of the distributor network was $3.451 million.” This model was consistent with – indeed, expressly allowed by – GlobeRanger Corp. v. Software AG, 836 F.3d 477, 499 (5th Cir. 2016). No. 18-20394 (July 11, 2019).

Tow v. Organo Gold Int’l presented a challenge, in a trade-secrets case, to a damages model based on “avoided costs” rather than “lost profits.” Specifically: “Weingust [Plaintiff’s expert] concluded that the distributor network was worth approximately $3.451 million based on the following two methodologies: the cost approach showed AmeriSciences had incurred about $6.2 million over five years to develop the distributor network, attract new distributors, and retain existing ones. The income approach considers how long income is expected from the asset and the amount of income each year. Weingust concluded the income approach dictated the network would generate $700,327 over ten years. Weingust testified that neither valuation method was better than the other, so he averaged the two to conclude the value of the distributor network was $3.451 million.” This model was consistent with – indeed, expressly allowed by – GlobeRanger Corp. v. Software AG, 836 F.3d 477, 499 (5th Cir. 2016). No. 18-20394 (July 11, 2019).

After a recent en banc vote, the full Fifth Circuit will engage an important limit on the power of the administrative state. The majority and dissenting opinons in Sierra Club v. Luminant Energy grappled with the “concurrent-remedies doctrine” and whether it created a limitations bar to an action for equitable relief under the Clean Air Act. No. No. 17-10235 (order issued June 10, 2019).

After a recent en banc vote, the full Fifth Circuit will engage an important limit on the power of the administrative state. The majority and dissenting opinons in Sierra Club v. Luminant Energy grappled with the “concurrent-remedies doctrine” and whether it created a limitations bar to an action for equitable relief under the Clean Air Act. No. No. 17-10235 (order issued June 10, 2019).

Hard-fought litigation about reform to Texas’s foster-care system led to an injunction, an appeal, a limited remand to revise the injunction, and a renewed appeal. The panel majority affirmed in part and reversed in part, finding, inter alia: (i) the revised injunction exceeded the mandate of the limited remand; (ii) that a requirement affirmed in the appeal was, upon further review, in fact unnecessary; and (iii) that a provision about data use required additional confidentiality safeguards.

Hard-fought litigation about reform to Texas’s foster-care system led to an injunction, an appeal, a limited remand to revise the injunction, and a renewed appeal. The panel majority affirmed in part and reversed in part, finding, inter alia: (i) the revised injunction exceeded the mandate of the limited remand; (ii) that a requirement affirmed in the appeal was, upon further review, in fact unnecessary; and (iii) that a provision about data use required additional confidentiality safeguards.

A strong dissent protested the overall lack of deference to the district court’s discretion, focusing in particular on a provision about “an integrated computer system to rationalize record keeping.” It argued that by vacating that provision, “the majority completes its walk away from the district court’s interlaced remedial scheme, taking away provisions essential to its success . . . a decision flawed by the evidence and controlling legal principles.” The dissent further observed: “[The State’s] reflexive resistance to the federal district court’s remedial orders–both direct confrontation and a refusal to cooperate or otherwise participate in the crafting of a response–bespeaks a view of our federalism inverted to look past the unchallenged finding of this court of the State’s deliberate indifference to the constitutional rights of PMC children . . . .” M.D. v. Abbott, No. 18-40057 (July 8, 2019).

“The complaint alleges that during the April and October 2016 phone calls, the defendants negligently misrepresented to Mr. Dick that ‘reinstatement was not an option’ and that ‘there was nothing [the] Plaintiff could do to stop a foreclosure.’ The plaintiff’s claim that these misrepresentations prevented her from reinstating the loan merely repackages her claim for breach of contract based on the duty to cooperate. It is therefore barred by the economic loss rule.” Dick v. Colorado Housing Enterprises LLC, No. 18-10900 (July 5, 2019) (unpublished).

“The complaint alleges that during the April and October 2016 phone calls, the defendants negligently misrepresented to Mr. Dick that ‘reinstatement was not an option’ and that ‘there was nothing [the] Plaintiff could do to stop a foreclosure.’ The plaintiff’s claim that these misrepresentations prevented her from reinstating the loan merely repackages her claim for breach of contract based on the duty to cooperate. It is therefore barred by the economic loss rule.” Dick v. Colorado Housing Enterprises LLC, No. 18-10900 (July 5, 2019) (unpublished).

Lake Eugenie Land & Devel. v. BP, the latest in the “body of federal common law in this Circuit” about the Deepwater Horizon settlement, presents both a crisp summary of the mandate rule and a dramatic tale of piracy on the high seas.

Lake Eugenie Land & Devel. v. BP, the latest in the “body of federal common law in this Circuit” about the Deepwater Horizon settlement, presents both a crisp summary of the mandate rule and a dramatic tale of piracy on the high seas.

Mandate rule. As to the mandate rule, the opinion succinctly summarizes its theoretical basis –

“The mandate rule is a subspecies of the law-of-the-case doctrine: When a court decides a question, it usually decides it once and for all ‘subsequent stages in the same case.’ This doctrine operates on a horizonal plane—constricting a later panel vis-à-vis an earlier panel of the same court. It also operates on a vertical plane—constricting a lower court vis-à-vis a higher court. The vertical variant is what we call the ‘mandate rule,’ and it’s the kind at issue here.”

(citations omitted), as well as the way to implement it: “The first step is figuring out what our mandate said. . . . The next question is whether the district court deviated from that mandate.” (citations omitted).

Piracy on the high seas. The opinion cites some 19th-Century authority about the foundations of the mandate rule; among them, Himley v. Rose, 9 U.S. (5 Cranch) 313 (1809), which involved a “decree . . . formerly rendered” about the restoration of cargo from the merchant ship Sarah. The earlier opinion, Rose v. Himley, 8 U.S. (4 Cranch) 241 (1808), presents an  amazing tale of a load of coffee, sent from the port of Santo Domingo by “brigands” during a slave revolt against the French government, which was then intercepted and seized by a French privateer and sold in Cuba.

amazing tale of a load of coffee, sent from the port of Santo Domingo by “brigands” during a slave revolt against the French government, which was then intercepted and seized by a French privateer and sold in Cuba.

Texas Capital Bank sued Zeidman for the alleged breach of a guaranty obligation. The Bank moved for summary judgment; in response, one of Zeidman’s arguments was that the Bank’s claim was barred by quasi-estoppel. He testified that “the Bank orally agreed to accept a $500,000 payment in satisfaction of the Guaranty, Zeidman wired that amount to the Bank, the Bank accepted the payment, and it later demanded additional payment under the Guaranty.” The Bank countered that this defense was barred by the statute of frauds, and the Fifth Circuit agreed that “oral modification of the Guaranty appears to be prohibited by the text of the Guaranty and the statute of frauds . . . .” But the Court found the Bank’s position about the statute of frauds to be inapplicable “because it improperly recharacterizes Zeidman’s affirmative defense as a claim that the underlying Guaranty was modified.” Texas Capital Bank N.A. v. Zeidman, No. 18-1114 (June 27, 2019) (unpubl.)

Texas Capital Bank sued Zeidman for the alleged breach of a guaranty obligation. The Bank moved for summary judgment; in response, one of Zeidman’s arguments was that the Bank’s claim was barred by quasi-estoppel. He testified that “the Bank orally agreed to accept a $500,000 payment in satisfaction of the Guaranty, Zeidman wired that amount to the Bank, the Bank accepted the payment, and it later demanded additional payment under the Guaranty.” The Bank countered that this defense was barred by the statute of frauds, and the Fifth Circuit agreed that “oral modification of the Guaranty appears to be prohibited by the text of the Guaranty and the statute of frauds . . . .” But the Court found the Bank’s position about the statute of frauds to be inapplicable “because it improperly recharacterizes Zeidman’s affirmative defense as a claim that the underlying Guaranty was modified.” Texas Capital Bank N.A. v. Zeidman, No. 18-1114 (June 27, 2019) (unpubl.)

The Fifth Circuit revised its original opinion in SEC v. Arcturus Corp., reaching the same result (reversal of a summary judgment for the SEC about whether certain investment contracts were securities), while adding significant factual and legal detail about the sophistication of the relevant investors – the issue on which the Court found summary judgment to have been inappropriate. SEC v. Arcturus Corp. (revised), No. 17-10503.

The Fifth Circuit revised its original opinion in SEC v. Arcturus Corp., reaching the same result (reversal of a summary judgment for the SEC about whether certain investment contracts were securities), while adding significant factual and legal detail about the sophistication of the relevant investors – the issue on which the Court found summary judgment to have been inappropriate. SEC v. Arcturus Corp. (revised), No. 17-10503.