This Instagram video with fonts talking to each other is really funny. Thanks to my law partner Mary Nix for sending it my way.

Category Archives: Legal Writing

Start the New Year out right with “Get the Last Word in an Effective Reply Brief,” which I recently co-wrote for the Bar Association of the Fifth Federal Circuit with my skillful colleague Campbell Sode – available here along with many other valuable practice pointers by members of that great bar association.

The Bar Association of the Fifth Federal Circuit is the bar association to belong to if you’re interested in the work of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. More information about member benefits is detailed on the BAFFC’s website. One of those benefits is a terrific set of short (c. 500 word) articles about appellate practice (here’s an example that I did about a year ago on oral-argument preparation).

The Bar Association of the Fifth Federal Circuit is the bar association to belong to if you’re interested in the work of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. More information about member benefits is detailed on the BAFFC’s website. One of those benefits is a terrific set of short (c. 500 word) articles about appellate practice (here’s an example that I did about a year ago on oral-argument preparation).

Please consider writing one yourself! A link will be emailed out several times to the BAFFC’s thousands of members, as part of its daily updates about recent decisions, and it’ll be available to the membership online as part of the full collection of these pieces. Contact BAFFC administrator Mary Douglas at mary@baffc.org!

Whatever your views of the remarkable civil-rights issue presented by Wilson v. Midland County (the intersection between some highly technical immunity rules and the bizarre injustice of a county employee working simultaneously for the prosecution and the courts), one can admire the deft prose of Jude Willett’s opinion:

An antitrust case in Tennessee recently produced a remarkably contentious dispute about the definition of “double spacing,” as deftly summarized in this “Above the Law” article titled “Heated Litigation Fight Over Double Spacing Ends in Judge Telling Everyone to Shut Up.” While the dispute was picayune, the discussion of just what exactly “double spacing” means is interesting background for a modern word-processing feature that we seldom stop and think about. Thanks to my law partner Chris Schwegmann for flagging this for me.

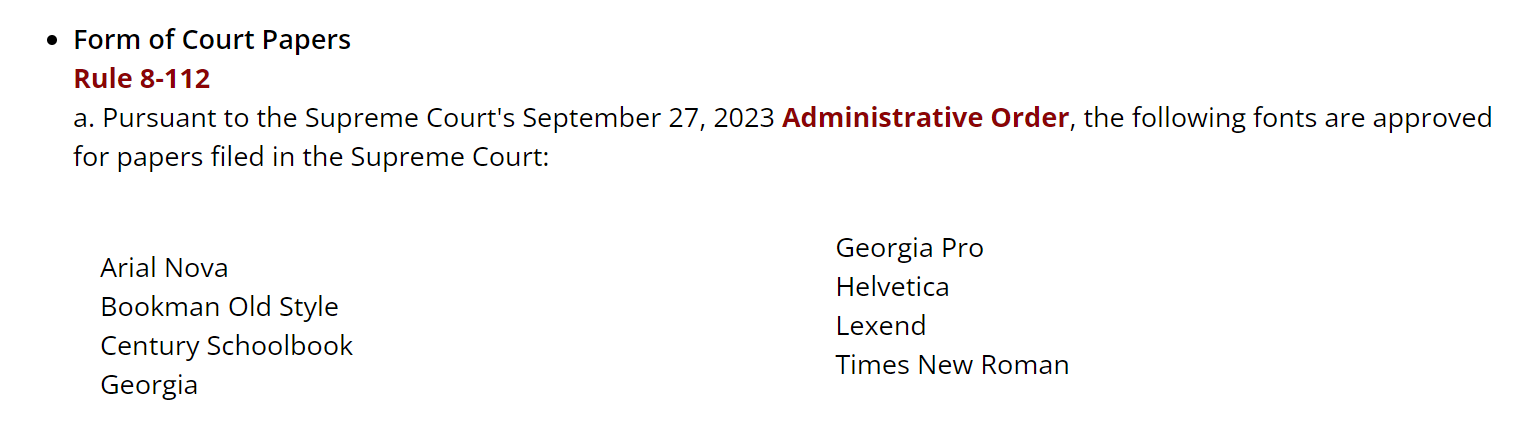

Thanks to a persuasive letter from a typographically sophisticated attorney, the Maryland Supreme Court recently recently modernized its list of acceptable fonts, as follows (omitting Palatino and Equity, however). Thanks to my law partner Greg Brassfield for drawing this to my attention!

Also of general interest, the letter links to an informative series of Tweets about the typography used in the federal courts of appeal.

Carbon Six Barrels, LLC v. Proof Research, Inc., a state-law trademark case about the design of gun barrels, turned on an Erie conclusion about Louisiana prescription law:

While true that Hogg and Crump arose in the context of damage to real property, we, like the district court, see no reason that the general principle those opinions announced should not apply here. The Louisiana Supreme Court made clear that “[t]he inquiry [as to a continuing tort] is essentially a conduct-based one, asking whether the tortfeasor perpetuates the injury through overt, persistent, and ongoing acts.” … This principle is not confined to the real property context. The district court was correct in stating that the earlier cases Carbon Six cites “are generally inconsistent with the [Louisiana] Supreme Court’s holding in Hogg,” and that “Louisiana law does not support the broad proposition that LUTPA’s prescriptive period is suspended as long as a perpetrator of fraud fails to correct his false statements.” This proposition would transform nearly every business dispute into a continuing tort.

(citations omitted). Also, I spoke about “AI and the Legal Profession” at the recent annual meeting of the Bar Association of the Fifth Federal Circuit, and used the briefs in this case to illustrate the capabilities (and deficiencies) of generative AI–here is my PowerPoint!

A recent Fifth Circuit panel produced three opinions on an organizational-standing issue in Louisiana Fair Housing Action Center, Inc. v. Azalea Garden Props., LLC.

Top-notch legal-writing expert Ross Guberman wrote an insightful LinkedIn post about Judge Elrod’s distinction of authority in her dissenting opinion – I recommend you give it a read!

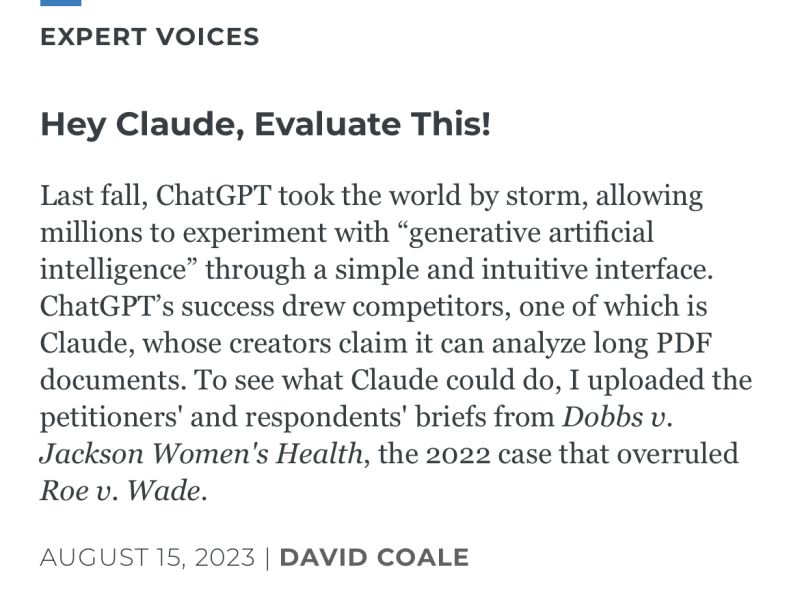

In last week’s Texas Lawbook, I reported on an experiment with an AI competitor of ChatGPT called Claude. It’s not ready to be a virtual law clerk yet, but its surprisingly powerful.

The recent en banc vote in Wearry v. Foster featured discussion of a “dubitante” opinion filed by a panel member. Unfamiliar with the term, I learned from Wikipedia that this phrase has a long and distinguished – if somewhat obscure – history in judicial opinions as a way for a judge to note his or her doubts about the rule of decision.

I then consulted my friend Brent McGuire, the pastor of Our Redeemer Lutheran Church in Dallas, who gave me further detail:

“Dubitante would literally mean ‘having doubts’ or “with a wavering [mind].’ It’s the singular participial form of the verb dubitō, dubitāre, which means to doubt or to waver. But that ‘e’ ending means it’s the ablative case, which is basically the adverbial case, that is to say, the case the noun or adjective takes when used to describe in some way a verb, adjective, or other adverb.”

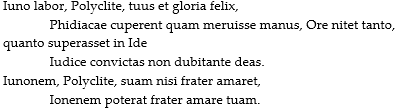

To illustrate its historical use, Pastor Maguire offered this epigram from Martial, found on the Tufts classical search engine:

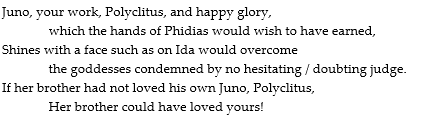

which he translates roughly as:

Pastor Maguire explains: “Martial is telling the sculptor Polyclitus that his statute of Juno is so beautiful that Paris (at that most fateful beauty pageant on Ida) would have picked it over Venus (Aphrodite) and Minerva (Athena) without hesitation. Moreover, if Jupiter had not already fallen for his actual sister Juno, he would have fallen in love for Polyclitus’s statue of her.” Conversely, then, a “dubitante” judge may have joined Paris’s conclusion, but with nagging doubts about the eternal beauty of the goddesses.

CFSA v. CFPB finds – again – that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is unconstitutionally structured, but this time because its “double insulated” funding mechanisms violated the Appropriations Clause by circumventing Congress’ “power of the purse.” The arguments about that fundamental Constitutional provision are intriguing and seem likely to draw the Supreme Court’s interest. No. 21-50826 (Oct. 19, 2022). The Fifth Circuit’s treatment creates a split with seven other federal courts, including PHH Corp. v. CFPB, 881 F.3d 75 (D.C. Cir. 2018). A recent Slate article offered criticism of the opinion.

The opinion also presents a rare appearance of the word “magisterial” to describe an earlier case on this topic:  Cf. Herman Hesse, “Magister Ludi” (1943).

Cf. Herman Hesse, “Magister Ludi” (1943).

The Onion, America’s Finest News Source, recently weighed in at SCOTUS with a brilliant amicus brief about First Amendment protection for parody; this excerpt summarizes the overall flavor:

When you next want to pose a question in your writing, and really really emphasize it, please consider . . . the Interrobang! Wikipedia suggests the below examples of when the Interrobang may be just the punctuation mark you’re looking for. (H/T to Lucy Forbes of Houston for her knowledge of unconventional punctuation marks)

When you next want to pose a question in your writing, and really really emphasize it, please consider . . . the Interrobang! Wikipedia suggests the below examples of when the Interrobang may be just the punctuation mark you’re looking for. (H/T to Lucy Forbes of Houston for her knowledge of unconventional punctuation marks)

If the details of the virgule are not obscure enough for you, then you will love this wonderful article from Smithsonian Magazine about the “pilcrow,” a/k/a the paragraph symbol.

If the details of the virgule are not obscure enough for you, then you will love this wonderful article from Smithsonian Magazine about the “pilcrow,” a/k/a the paragraph symbol.

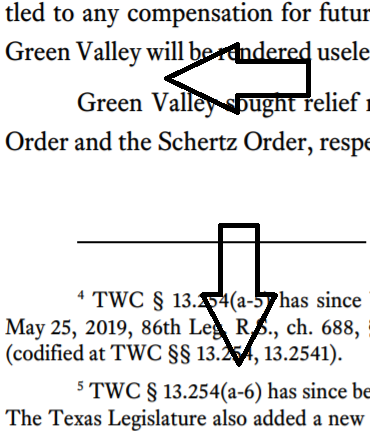

The London Underground reminds its riders to “Mind the Gap” so they do not trip when entering or exiting a train. The Fifth Circuit’s new typography places a notable gap between paragraphs and footnotes. While this sort of line-spacing does not have a technical label like “kerning,” it is nevertheless an important part of the overall look and feel of a piece of legal writing. What are your thoughts on inter-paragraph line spacing?

The London Underground reminds its riders to “Mind the Gap” so they do not trip when entering or exiting a train. The Fifth Circuit’s new typography places a notable gap between paragraphs and footnotes. While this sort of line-spacing does not have a technical label like “kerning,” it is nevertheless an important part of the overall look and feel of a piece of legal writing. What are your thoughts on inter-paragraph line spacing?

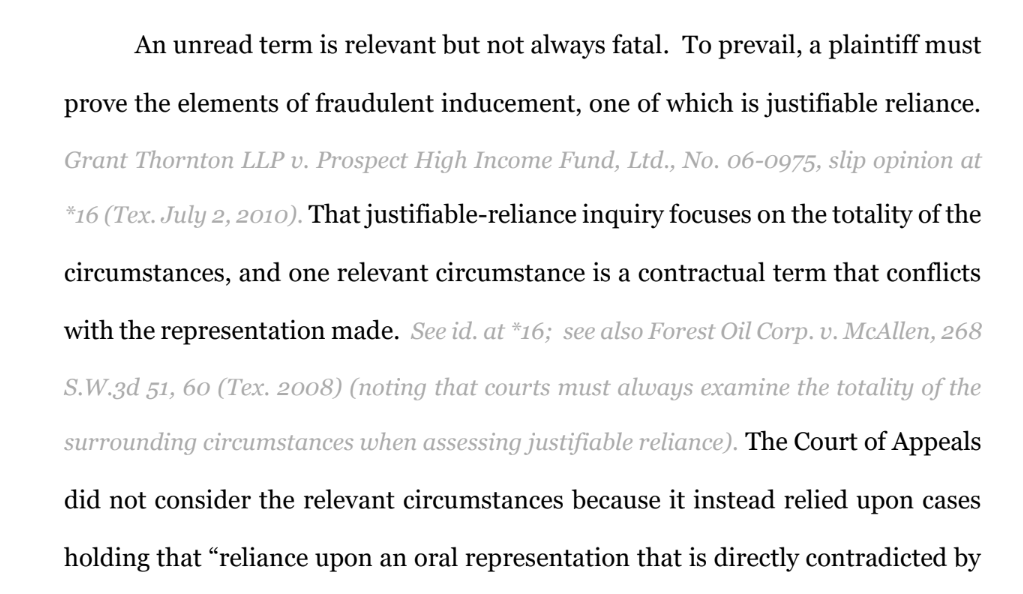

When not engaged in good-natured banter about typeface or proper spacing after periods, the appellate community often argues about the right place to put citations to authority. The traditional approach places them “inline,” along with the text of the legal argument. A contrarian viewpoint, primarily advanced by Bryan Garner, argues that citations should be placed in footnotes.

Has modern technology provided a third path? Professor Rory Ryan of Baylor Law School advocates “fadecites,” reasoning:

A brief using this approach would look like this on a first read:

(A longer example is available on Professor Ryan’s Google Drive.) The reader can quickly skim over citations while reviewing the legal argument. Additionally, assuming that the court’s technology allows it, case citations can be arranged to become more visible if the reader wants to know more information. Modern .pdf technology allows a citation to become darker and more visible if the reader places the cursor on it. A hyperlink to the cited authority could also be made available.

This idea offers an ingenious solution to a recurring challenge in writing good, accessible briefs. I’d be interested in your thoughts and Professor Ryan would be as well.

With the kids home from school because of the coronavirus, I’ve watched a lot of YouTube videos over their shoulders. In particular, this one tells the fascinating story about how post-production editing saved Star Wars, which was bloated and impossible to follow in its first rough versions. Among

With the kids home from school because of the coronavirus, I’ve watched a lot of YouTube videos over their shoulders. In particular, this one tells the fascinating story about how post-production editing saved Star Wars, which was bloated and impossible to follow in its first rough versions. Among  other changes, the start of the film was drastically simplified – from a series of back-and-forths between space and Tatooine, to a focus on the opening space battle and no shots of Tatooine until the droids landed there. This bit of editing is directly relevant to the tendency of legal writers to “define” (introduce) all characters and terms at the beginning of their work, without regard to the flow of the narrative that follows.

other changes, the start of the film was drastically simplified – from a series of back-and-forths between space and Tatooine, to a focus on the opening space battle and no shots of Tatooine until the droids landed there. This bit of editing is directly relevant to the tendency of legal writers to “define” (introduce) all characters and terms at the beginning of their work, without regard to the flow of the narrative that follows.

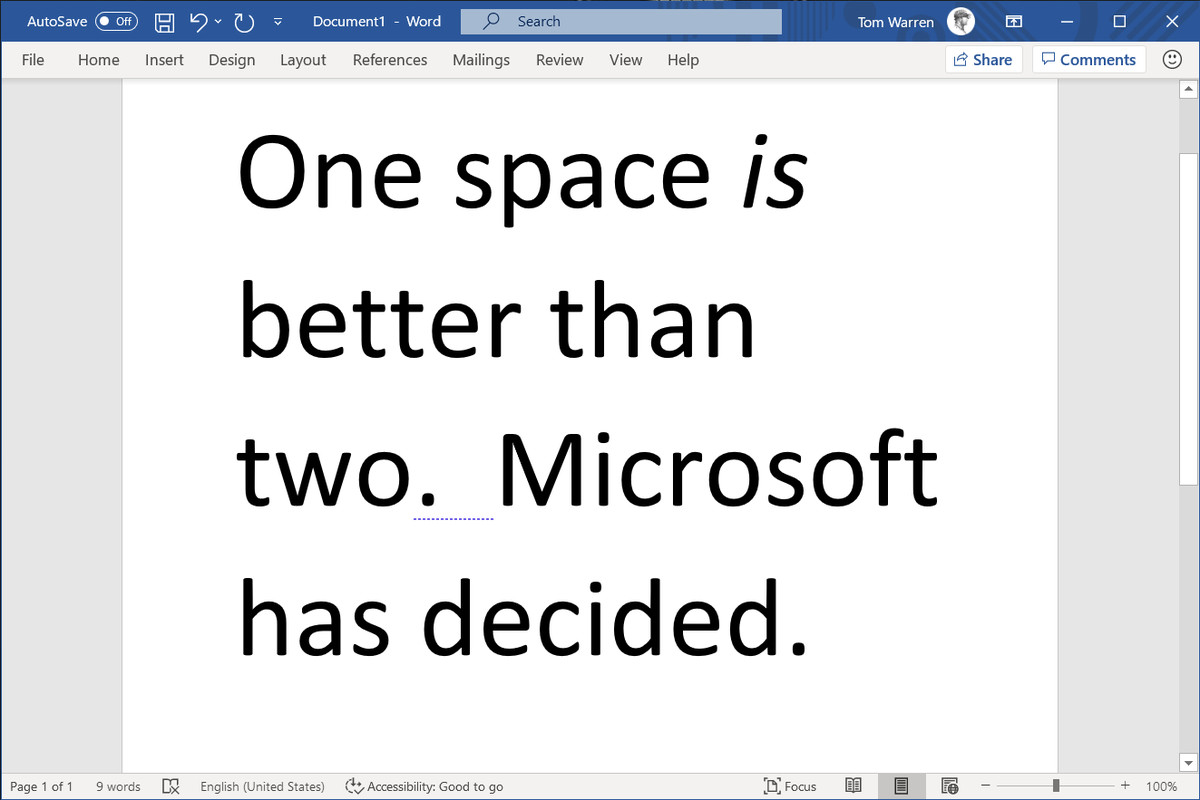

As reported by The Verge on April 24, Microsoft Word now auto-corrects the use of two spaces after a period at the end of a sentence. The battle, such as it was, should now be considered over. This influential article in Slate explains why the one-spacers – while correct during the era of typewriters, which made every letter and space the same size – have been wrong since the early 1990s and the widespread availability of proportional spacing in modern word processing software.

As reported by The Verge on April 24, Microsoft Word now auto-corrects the use of two spaces after a period at the end of a sentence. The battle, such as it was, should now be considered over. This influential article in Slate explains why the one-spacers – while correct during the era of typewriters, which made every letter and space the same size – have been wrong since the early 1990s and the widespread availability of proportional spacing in modern word processing software.