“Hard cases make bad law,” says the old adage; whether that holds true for Taylor v. Riojas, will remain to be seen. The Supreme Court reversed a qualified-immunity ruling in a case involving what it saw as “shockingly unsanitary” prison cells, finding that the “extreme circumstances” of the case eliminated any dispute about whether the relevant law was clearly-established. No. 19-1261 (U.S. Nov. 2, 2020) (reversing Taylor v. Stevens, 946 F.3d 211 (5th Cir. 2019).

Monthly Archives: November 2020

Doe, a police officer, sued under Louisiana state law for injuries that he suffered when trying to clear a highway of protesters, who had been organized by McKesson. The district court dismissed the case on First Amendment grounds; a Fifth Circuit panel majority “held that a jury could plausibly find that Mckesson breached his ‘duty not to negligently precipitate the crime of a third party’ because ‘a violent confrontation with a police officer was a foreseeable effect of negligently directing a protest’ onto the highway, and the en b anc court divided -8 on whether to further review the case.

anc court divided -8 on whether to further review the case.

The Supreme Court held that the issue should be certified to the Louisiana Supreme Court, noting that “the dispute presents novel issues of state law peculiarly calling for the exercise of judgment by the state courts,” and that “certification would ensure that any conflict in this case between state law and the First Amendment is not purely hypothetical. The novelty of the claim at issue here only underscores that ‘[w]arnings against premature adjudication of constitutional questions bear heightened attention when a federal court is asked to invalidate a State’s law.'” McKesson v. Doe, No.19–1108 (U.S. Nov. 2, 2020) (citation omitted).

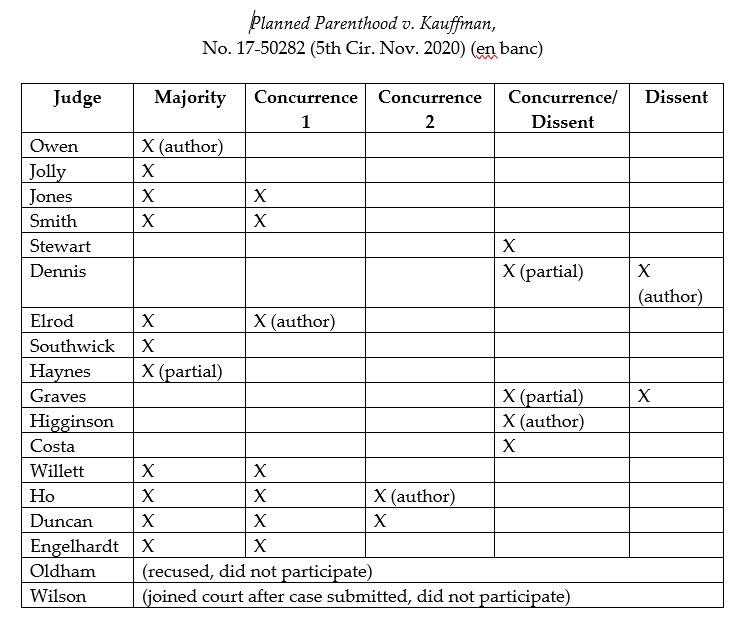

The dry-sounding issue before the en banc court in Planned Parenthood v. Kauffman, No. 17-50282 (Nov. 23, 2020), was “whether 42 U.S.C. § 1396a(a)(23) gives Medicaid patients a right to challenge, under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, a State’s determination that a health care provider is not ‘qualified’ within the meaning of § 1396a(a)(23).” The practical consequence of that issue, however, is significant–who may sue about Texas’s termination of several Planned Parenthood facilities from that state’s Medicaid program.

The majority held that under a 1980 Supreme Court case and the structure of the statute, the patients did not have the right to sue. In so doing, the Fifth Circuit joined the Eighth Circuit and split with five others. A 7-judge concurrence (2 votes shy of a majority, given the configuration of the en banc court for this case) would have reached the merits and rejected them. The opinions are illustrated in the chart below:

The Fifth Circuit recently decided to take three matters en banc:

The Fifth Circuit recently decided to take three matters en banc:

- Cochran v. SEC, 969 F.3d 507 (2020): “Judicial review of Securities and Exchange Commission proceedings lies in the courts of appeals after the agency rules. 15 U.S.C. § 78y. This appeal asks whether a party may nonetheless raise a constitutional challenge to an SEC enforcement action in federal district court before the agency proceeding ends.”

- Sanchez v. Smart Fabricators, 970 F.3d 550 (2020), in which all three panel members urged the en banc court to address Circuit precedent about the definition of a seaman; and

- Whole Woman’s Health v. Paxton, No. 17-51060 (Oct. 13, 2020), an abortion case in which the panel disagreed about the effect of June Medical Services LLC v. Russo, 140 S. Ct. 2103 (2020).

“Sharing liability is not the same as sharing an identity. As our colleagues in the Ninth Circuit explained, ‘Liability and jurisdiction are independent. . . . Regardless of their joint liability, jurisdiction over each defendant must be established individually.’ Lumping defendants together for jurisdictional purposes merely because they are solidary obligors ‘is plainly unconstitutional.'” Libersat v. Sundance Energy, No. 20-30121 (Oct. 26, 2020) (citation omitted, emphasis added).

“Sharing liability is not the same as sharing an identity. As our colleagues in the Ninth Circuit explained, ‘Liability and jurisdiction are independent. . . . Regardless of their joint liability, jurisdiction over each defendant must be established individually.’ Lumping defendants together for jurisdictional purposes merely because they are solidary obligors ‘is plainly unconstitutional.'” Libersat v. Sundance Energy, No. 20-30121 (Oct. 26, 2020) (citation omitted, emphasis added).

The novelty of the international-discovery procedure in 28 USC § 1782 intersected with the collateral-order doctrine about interlocutory appeals in Banca Pueyo SA v. Lone Star Fund: “While we readily conclude that this appeal was premature, we recognize that the unusual nature of section 1782 proceedings results in some uncertainty about when to appeal. Indeed, respondents acknowledged that this might not be the right time, but they appealed now in an abundance of caution. They also worry that an appeal may never be ripe due to the possibility of a future dispute over privilege. But appellate jurisdiction is a ‘practical’ determination, not a speculative one. Once the district court fully resolves the second motion to quash, the scope of section 1782 discovery should be definitively resolved. When that conclusive determination comes, an appeal would be appropriate.” No. 20-10049 (Oct. 27, 2020) (mem. op.).

The novelty of the international-discovery procedure in 28 USC § 1782 intersected with the collateral-order doctrine about interlocutory appeals in Banca Pueyo SA v. Lone Star Fund: “While we readily conclude that this appeal was premature, we recognize that the unusual nature of section 1782 proceedings results in some uncertainty about when to appeal. Indeed, respondents acknowledged that this might not be the right time, but they appealed now in an abundance of caution. They also worry that an appeal may never be ripe due to the possibility of a future dispute over privilege. But appellate jurisdiction is a ‘practical’ determination, not a speculative one. Once the district court fully resolves the second motion to quash, the scope of section 1782 discovery should be definitively resolved. When that conclusive determination comes, an appeal would be appropriate.” No. 20-10049 (Oct. 27, 2020) (mem. op.).

Richardson v. Flores reviewed the standards for intervention into an ongoing appeal, noting: “There is no appellate rule allowing intervention generally. Instead, the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure contemplate intervention only in

Richardson v. Flores reviewed the standards for intervention into an ongoing appeal, noting: “There is no appellate rule allowing intervention generally. Instead, the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure contemplate intervention only in

proceedings to review agency action. Fed. R. App. P. 15(d). But despite the lack of an on-point rule, we have allowed intervention in cases outside the scope of Rule 15(d). . . . Perhaps because there is no rule explicitly allowing intervention on appeal, the caselaw explicating the standards for such motions is scarce. In Bursey, when granting a similar motion to intervene, we said ‘a court of appeals may,  but only in an exceptional case for imperative reasons, permit intervention where none was sought in the district court.'” (footnote and citations omitted, emphasis in original). The Court also noted: “Motions to intervene on appeal are different from motions to intervene for purposes of appeal. Motions to intervene for purposes of appeal are used where ‘the existing parties have decided not to pursue [an appeal]’ and are filed in district courts in the first instance under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.” (citation omitted).

but only in an exceptional case for imperative reasons, permit intervention where none was sought in the district court.'” (footnote and citations omitted, emphasis in original). The Court also noted: “Motions to intervene on appeal are different from motions to intervene for purposes of appeal. Motions to intervene for purposes of appeal are used where ‘the existing parties have decided not to pursue [an appeal]’ and are filed in district courts in the first instance under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.” (citation omitted).

Who knew? The federal bench in Houston just released an inspiring rendition of “We’ll Be Back” from Hamilton, revised to reflect life in the COVID-19 pandemic. Bravo!

Who knew? The federal bench in Houston just released an inspiring rendition of “We’ll Be Back” from Hamilton, revised to reflect life in the COVID-19 pandemic. Bravo!

The defendant in Coastal Bridge Co. v. Heatec, No. 19-31030 (revised Nov. 6, 2020) made a spoliation claim about the loss of a heater involved in a fire. The Fifth Circuit reasoned:

- “As a threshold matter, Because Coastal Bridge reasonably should have anticipated litigation over the fire damage, it had a duty to preserve the equipment.”

- But bad faith was not shown: “Adherence to normal operating procedures may counter a contention of bad faith. Here, an outdoor piece of industrial equipment was stored outdoors. The record does not support the finding that Coastal Bridge acted with a culpable state of mind.”

- And as to relevance: “Heatec did not specifically request to examine the pumps at the joint inspection. As such, the pumps are of questionable relevance for the purposes of its underlying claim that poor pump maintenance can be a cause of a heater fire.”

Billy Joel disputed causation about starting the fire. So did the parties in Coastal Bridge Co. v. Heatec, in which the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment, holding: “Here, genuine disputes of material fact exist as to: (1) the significance of the heating pumps; (2) what

Billy Joel disputed causation about starting the fire. So did the parties in Coastal Bridge Co. v. Heatec, in which the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment, holding: “Here, genuine disputes of material fact exist as to: (1) the significance of the heating pumps; (2) what  equipment was disassembled and disposed of; (3) the origin of the subject fire and whether the inlet pipe moved; and (4) the extent of communication4 that occurred between the parties before the formal notice of the fire. These factual disputes cannot be resolved without weighing the evidence and making credibility determinations, which are matters for the factfinder.” No. 19-31030 (Nov. 6, 2020, revised).

equipment was disassembled and disposed of; (3) the origin of the subject fire and whether the inlet pipe moved; and (4) the extent of communication4 that occurred between the parties before the formal notice of the fire. These factual disputes cannot be resolved without weighing the evidence and making credibility determinations, which are matters for the factfinder.” No. 19-31030 (Nov. 6, 2020, revised).

Each of the four factors for a deadline extension was in play in AIG Europe, Inc. v. Caterpillar, Inc., No. 19-40934, where the Fifth Circuit observed:

Each of the four factors for a deadline extension was in play in AIG Europe, Inc. v. Caterpillar, Inc., No. 19-40934, where the Fifth Circuit observed:

- Explanation. “If AIG needed information from Caterpillar’s experts to allow Faherty to complete his expert report, AIG should have moved to compel the depositions of those experts.”

- Importance. “AIG’s claims do not turn on Faherty’s report. Despite the exclusion, AIG had experts on causation.”

- Prejudice. “Faherty’s report responded to the analysis of Caterpillar’s experts, it also contained new analyses and conclusions. Defendants were not given the opportunity to challenge these conclusions on the critical issue of causation.”

- Continuance? “Yet another continuance would have delayed summary judgment and a potential trial even further.”

An “area developer” for Pizza Inn did not timely renew his option contract related to the potential development of new stores. The Fifth Circuit reversed a judgment for the developer, finding that Texas’s doctrine of “equitable intervention” did not apply. The alleged harms from nonrenewal–“a partial forfeiture of a $1,250,000 purchase price, a forfeiture of future profits . . . , and the shuttering of a Pizza Inn franchise store”–were either within the scope of the contractual bargain or simply not unconscionable, as required by the doctrine. Pizza Inn v. Cairday, No. 19-11302 (Nov. 4, 2020).

An “area developer” for Pizza Inn did not timely renew his option contract related to the potential development of new stores. The Fifth Circuit reversed a judgment for the developer, finding that Texas’s doctrine of “equitable intervention” did not apply. The alleged harms from nonrenewal–“a partial forfeiture of a $1,250,000 purchase price, a forfeiture of future profits . . . , and the shuttering of a Pizza Inn franchise store”–were either within the scope of the contractual bargain or simply not unconscionable, as required by the doctrine. Pizza Inn v. Cairday, No. 19-11302 (Nov. 4, 2020).

The issue in 9503 Middlex, Inc. v. Continental Motors, Inc., No. 19-50361 (Nov. 2, 2020) (unpublished), was whether a commercial tenant was “holding over in possession,” and the Fifth Circuit held it was not: “Here, the district court found that the combination of (1) the retention of the keys to the gate, (2) the use of the gate as a shortcut, and (3) the use of the premises as a break area “constituted holding over.” We agree they are relevant evidence, but we do not agree that they are sufficient. Continental did not occupy the premises of Buildings E and F, nor did Continental exercise dominion over the premises. Continental surrendered the properties to the plaintiffs, though it retained a key to an outside gate. We do not see support in the caselaw that a tenant occupies or controls property when something occurs as insignificant as when employees eat lunch at picnic tables on that property.”

The issue in 9503 Middlex, Inc. v. Continental Motors, Inc., No. 19-50361 (Nov. 2, 2020) (unpublished), was whether a commercial tenant was “holding over in possession,” and the Fifth Circuit held it was not: “Here, the district court found that the combination of (1) the retention of the keys to the gate, (2) the use of the gate as a shortcut, and (3) the use of the premises as a break area “constituted holding over.” We agree they are relevant evidence, but we do not agree that they are sufficient. Continental did not occupy the premises of Buildings E and F, nor did Continental exercise dominion over the premises. Continental surrendered the properties to the plaintiffs, though it retained a key to an outside gate. We do not see support in the caselaw that a tenant occupies or controls property when something occurs as insignificant as when employees eat lunch at picnic tables on that property.”

The University of Texas’s rules about campus speech did not fare well in Speech First, Inc. v. Fenves, in which the Fifth Circuit found that a preliminary-injunction action could proceed. The Court found that the case was not moot and stated a strong claim on the merits: “Of course, not every utterance is worth protecting under the First Amendment. In our current national condition, however, in which ‘institutional leaders, in a spirit of panicked damage control, are delivering hasty and disproportionate punishment instead of considered reforms,’ courts must be especially vigilant against assaults on speech in the Constitution’s care. Otherwise, the people may not be free to generate, debate, and discuss both general and specific ideas, hopes, and experiences,’ to ‘transmit their resulting views and conclusions to their elected representatives,’ ‘to influence the public policy enacted by elected representatives,’ and thereby to realize the political and human common good.” No. 19-50529 (revised Oct. 30, 2020) (footnotes omitted).

The University of Texas’s rules about campus speech did not fare well in Speech First, Inc. v. Fenves, in which the Fifth Circuit found that a preliminary-injunction action could proceed. The Court found that the case was not moot and stated a strong claim on the merits: “Of course, not every utterance is worth protecting under the First Amendment. In our current national condition, however, in which ‘institutional leaders, in a spirit of panicked damage control, are delivering hasty and disproportionate punishment instead of considered reforms,’ courts must be especially vigilant against assaults on speech in the Constitution’s care. Otherwise, the people may not be free to generate, debate, and discuss both general and specific ideas, hopes, and experiences,’ to ‘transmit their resulting views and conclusions to their elected representatives,’ ‘to influence the public policy enacted by elected representatives,’ and thereby to realize the political and human common good.” No. 19-50529 (revised Oct. 30, 2020) (footnotes omitted).