My thoughtful friend Arturo Ayala recently wrote this informative short article as to when partial supersedeas bonds may be allowed.

Category Archives: Appellate Procedure

State of Mississippi v. JXN Water addressed whether an order compelling the disclosure of SNAP recipient data qualifies as an appealable collateral order.

State of Mississippi v. JXN Water addressed whether an order compelling the disclosure of SNAP recipient data qualifies as an appealable collateral order.

Remininding that the requirements for a collateral order are “stingent,” the Fifth Circuit found them satisfied here. The order (1) conclusively determined a disputed question, (2) resolved an important issue separate from the merits of the case, and (3) was functionally unreviewable on appeal from a final judgment. On the last point, the Court emphasized that once the confidential information of SNAP recipients is released, “no relief can make the information confidential again.” No. 24-60309, Apr. 10, 2025

My friend Arturo Ayala at CSBA recently wrote this useful article about what happens to a supersedeas bond when the appeal ends.

A panel majority, after a motions panel accepted an interlocutory appeal, dismissed that appeal for lack of jurisdiction. The issue involved the appropriate measure for the calculation of “reasonable royalty” damages, and the majority reasoned:

If we reversed now, we would have no “immediate impact on the course of the litigation” because Silverthorne has not yet proven liability. The parties will proceed to trial regardless of whether we weigh in, and “nothing that we can do will prevent [the] trial.” Bear Marine, If Silverthorne fails to establish liability, our premature answer to the question will not have affected the litigation at all. Any dispute

about damages will have “evaporate[d] in the light of full factual development.”Even assuming arguendo that Silverthorne could establish liability, thereasonable-royalty standard may still not be controlling. Silverthorne claims that the district court’s order prevents it from proving damages. If that were true, the question could have controlled the case. As the district court noted, though, its order did “not automatically bar [Silverthorne] from proving damages,” as long as it does so according to the standard defined in [precedent].”

J.A. Masters Investments v. Beltramini, No. 24-20006 (Jan. 3, 2025) (citations and footnote omitted). A dissent had a different view of the legal issue and the section 1292 process.

This notice, under Fifth Circuit precedent, abandoned the lender’s intent to accelerate a note obligation:

This notice, under Fifth Circuit precedent, abandoned the lender’s intent to accelerate a note obligation:

To the extent you have received demand letters with intent to accelerate the obligations under the above subject Note and any notice of acceleration of said Note prior to the date of this demand letter, be advised that any such demands or notices of acceleration have been withdrawn, cancelled, and abandoned.

No. 23-50662 (Dec. 20, 2024) (emphasis in original). The opinion discusses how the Circuit’s “rule of orderliness” applies to the issue at hand.

The case of Chaudhary Law Firm, P.C. v. Ali reminds: “It is more than well-settled that only an aggrieved party may appeal a judgment.” A party is not considered “aggrieved” if they have received a favorable judgment, even if the trial court made subsidiary findings or conclusions that were unfavorable to them.

The case of Chaudhary Law Firm, P.C. v. Ali reminds: “It is more than well-settled that only an aggrieved party may appeal a judgment.” A party is not considered “aggrieved” if they have received a favorable judgment, even if the trial court made subsidiary findings or conclusions that were unfavorable to them.

The Court emphasized that “appellate courts review judgments, not opinions,” and a winning party “may not appeal for the sole purpose of seeking a more favorable opinion from the [trial] court.” The Court noted some situations that could warrant a relaxation of this principle, none of which were present in this case, where the defendant law firm obtained complete dismissal on the merits. No. 23-20362 (Dec. 9, 2024).

The appellants in Legacy Recovery Servcs, LLC v. City of Monroe tried mightily, but was unable to persuade the Fifth Circuit that it had appellate jurisdiction over an order that partially granted and denied motions to dismiss.

The appellants argued that the ruling was an appelable collateral order. The Court saw otherwise, holding that the order did not “conclusively determine the disputed question” because it dismissed some claims while retaining others. Exercising jurisdiction over such an order risked encouraging piecemeal appeals that would require the Court to review the same intertwined claims multiple times.

Also, the issues resolved by the district court were not “completely separate from the merits of the action.” The dismissed and retained claims were based on the same statutes, and thus interwoven with the issues left before the district court.

Lastly, the Court held that the order was not “effectively unreviewable on appeal from a final judgment,” pointing out that if the appellants’ concerns were valid, the Court could vacate the judgment and order a new trial after final judgment. No. 24-30211 (Nov. 6, 2024).

The party-presentation principle made an appearance yesterday in the “buoy case,” United States v. Abbott.

The specific issue is unique to this case, but the level of generality at which the Court identified the problem is of broader interest. Cf. United Natural Foods, Inc. v. NLRB, 66 F.4th 536, 556 (5th Cir. 2023) (Oldham, J., dissenting) (“Does anyone think that, when a party presents legal question X for decision in federal court, a federal judge is somehow disabled from reading any case, statute, regulation, or other authority not cited in the party’s brief? Of course not. We are duty-bound to understand the legal questions presented to us—even when a party presents a question less than perfectly.”).

(To learn more about this elusive but important principle, you can read my recent article in the Cornell Law Review Online).

Airlines for Am. v. Dep’t of Transp. illustrates how the issue of interim appellate relief stays (rimshot) in flux. The panel majority said:

Several airlines and airline associations seek a stay pending review of a recent Department of Transportation (“DOT”) Rule that regulates how airlines disclose fees to consumers during the booking process. Finding the Rule likely exceeds DOT’s authority and will irreparably harm airlines, we GRANT the requested stay and EXPEDITE the petition for review.

A third judge would have taken a more staid approach:

In Lewis v. Crochet, the Fifth Circuit found that a ruling about the attorney-client privilege was properly appealed under the “collateral order” doctrine, applying Mohawk Indus. v. Carpenter, 558 U.S. 100, 103 (2009).

Lest one think the law of adminstrative stays had become more settled with time, MCR Oil Tools, LLC v. U.S. Dep’t of Transp. reminds otherwise. The manufacturer of a torch used in oil drilling challenged a new safety regulation on its product. The three judges on the panel reacted in different ways:

- The majority opinion defers the motion for stay to the next available argument panel;

- A dissent emphasized the need for immediate action, given the regulation’s effect on significant outstanding orders;

- A concurrence analogized the case to a recent challenge to the Texas ban on drag shows.

No. 24-60230 (May 23, 2024).

In Wilmington Savings Fund Society, FSB v. Myers, the appellant argued that its notice of appeal was timely, when filed within 30 days of a second judgment, and when the first judgment “was mislabeled because even though it purported to dispose of all claims and parties in the case, the title of the order did not signal that it was a final judgment.”

In Wilmington Savings Fund Society, FSB v. Myers, the appellant argued that its notice of appeal was timely, when filed within 30 days of a second judgment, and when the first judgment “was mislabeled because even though it purported to dispose of all claims and parties in the case, the title of the order did not signal that it was a final judgment.”

The Fifth Circuit agreed. Noting that “[o]rdinarily, such minor changes to an order do not ‘disturb or revise legal rights and obligations’ of the parties” (cleaned up), it concluded that “there was in this case a clear discrepancy between the label and the body of the district court’s order” that was sufficient to treat it as a substantive revision for purposes of calculating the appeal deadline. No. 24-20018 (March 18, 2024) (applying FTC v. Minneapolis-Honeywell Regulator Co., 344 U.S. 206, 211 (1952)).

(The graphic was provided by DALL-E, and explained by it as follows: “The images above illustrate the concept of a substantive change versus a change solely of form, through the comparison of a caterpillar’s transformation into a butterfly (substantive change) and a chameleon’s color change (change of form).”

The Fifth Circuit reminded about the basics of issue statements in Smith v. Delta Charter Group, Inc.:

Delta also forfeited its argument that the district court should have instead applied Rule 54(b). Delta didn’t include this argument in its “Statement of the Issue” or in the body of its opening brief—rather, Delta relegated it to a footnote. We have repeatedly cautioned that arguments appearing only in footnotes are “insufficiently addressed in the body of the brief” and are thus forfeited. Delta’s Rule 54(b) argument meets this predictable fate.

No. 23-30063 (Dec. 13, 2023). Note that this is NOT a criticism of the “citational footnote”–and in fact, the concept of the citational footnote rejects this sort of stealthy, footnote-only legal argument.

“Here, ‘all parties have agreed from the beginning of this case that Houston’s voter registration provisions governing circulators’ are unconstitutional. The City also agreed that it ‘would and could not enforce the provisions.’ The City has repeatedly and consistently emphasized its agreement with the plaintiffs throughout this suit. Such faux disputes do not belong in federal court.”

Pool v. City of Houston, No. 22-20491 (Dec. 11, 2023) (citations omitted).

A series of cases about the EPA’s regulation of small refineries led to a disagreement about Circuit venue over this kind of administrative-agency challenge. A majority appled a two-part test focused on whether the agency action was “nationally applicable”; the dissent rejected the majority’s analysis as inconsistent with statutory text, purpose, and structure. No. 22-60266 etc. (Nov. 22, 2023).

A series of cases about the EPA’s regulation of small refineries led to a disagreement about Circuit venue over this kind of administrative-agency challenge. A majority appled a two-part test focused on whether the agency action was “nationally applicable”; the dissent rejected the majority’s analysis as inconsistent with statutory text, purpose, and structure. No. 22-60266 etc. (Nov. 22, 2023).

The question in Elmen Holdings, LLC v. Martin Marietta Mat’ls, Inc. was whether a gravell-mining lease had terminated. The district court included that it had been terminated, and the appellant’s first issue was that the court’s analysis went too far under the “party-presentation” principle — a concept given new life and relevance by United States v. Sineneng-Smith, 140 S. Ct. 1575 (2020).

The question in Elmen Holdings, LLC v. Martin Marietta Mat’ls, Inc. was whether a gravell-mining lease had terminated. The district court included that it had been terminated, and the appellant’s first issue was that the court’s analysis went too far under the “party-presentation” principle — a concept given new life and relevance by United States v. Sineneng-Smith, 140 S. Ct. 1575 (2020).

The Fifth Circuit concluded that while the appellant’s argument “had some merit,” the trial court did not go too far:

The Fifth Circuit concluded that while the appellant’s argument “had some merit,” the trial court did not go too far:

“[T]he magistrate judge recommended granting Elmen’s motion for summary judgment because Martin Marietta had been late on several royalty payments. The magistrate judge did not ‘radical[ly] transform[]’ this case to such an extent as to constitute an abuse of discretion; she merely took a different route than Martin Marietta and Elmen had suggested to ;decide . . . questions presented by the parties.’ Therefore, the magistrate judge did not violate the party presentation principle by interpreting the Gravel Lease to terminate automatically upon a missed royalty payment, even if that interpretation was contrary to the parties’ reading of their contract.”

No. 23-20023 (Nov. 15, 2023); cf. United Natural Foods v. NLRB, 66 F.4th 536 (5th Cir. 2023) (majority and dissent disagree about whether a particular line of argument is allowed by the party-presentation principle).

During an Erie analysis of a Louisiana-law issue, the Fifth Circuit observed: “We are ‘a strict stare decisis court,’ meaning that a prior panel’s interpretation of state law is ‘no less binding on subsequent panels than are prior interpretations of federal law.'” QBE Syndicate 1036 v. Compass Minerals Louisiana, Inc., No. 23-30076 (Oct. 12, 2023). What distinguishes a “strict stare decisis court” from a less-strict one is not entirely clear, but the application of the “rule of orderliness” to state-law issues is well settled.

The remand of Collins v. Yellen, 141 S. Ct. 1761 (2020) did not end well for the plaintiffs, as the district court concluded that they “had not plausibly alleged that the removal restriction” on FHFA’s director caused them harm. The plaintiffs made a valiant effort to bring the case within the scope of a recent Fifth Circuit holding about the Appropriations Clause, but the Fifth Circuit found that its holding in that case did not create a change in the relevant law that was sufficient to overcome the mandate rule. Collins v. Dep’t of the Treasury, No. 22-20632 (Oct. 12, 2023).

SXSW, LLC v. Federal Ins. Co., an insurance-coverage case arising out of the 2020 cancellation of South by Southwest because of COVID-19, presented some “evergreen” issues about LLCs and diversity jurisdiction that led to a remand for further development of the record. The Fifth Circuit noted “at least three potential jurisdictional

defects” on the record presented–

- “First, there is a potentially important difference between LLC membership and LLC ownership. State law governs LLC formation and organization. Several states permit LLC membership without ownership. … SXSW has not shown the relevant LLCs were formed in States that equate membership and ownership.”

- “Second, SXSW stated that Capshaw [an LLC owner] was a Virginia resident. But residency is not citizenship for purposes of § 1332.”

- “Finally, there is a timing issue. For diversity jurisdiction, we look to citizenship at the time the complaint was filed. The complaint makes no allegations about the citizenship of SXSW’s members. Federal’s December 14, 2021 exhibit contains some additional information, as does SXSW’s February 22, 2023 appellant brief.But we have no way of knowing whether those later documents reflect SXSW’s membership structure as of October 6, 2021.”

No. 22-50933 (Oct. 5, 2023) (citations omitted, emphasis added).

Missouri v. Biden, No. 23-30445, presents a high-profile dispute about coordination betwen the federal government and social media platforms to address misinformation. A district court in Louisiana issued an injunction against such coordination and the federal government appealed. That appeal, as do many significant constitutional disputes, implicated the division of responsibility between an initial “administrative stay,” a later “stay pending appeal,” and the resolution of the merits of the appeal. For this case, a Fifth Circuit panel resolved that matter with this order:

In a recent analysis of a sanctions order, the Fifth Circuit provided an instructive example of an argument that withstood a forfeiture objection:

In a recent analysis of a sanctions order, the Fifth Circuit provided an instructive example of an argument that withstood a forfeiture objection:

“Ticket argues that CEATS forfeited the bad-faith argument by failing to assert it in the district court. While it is true that we tend not to entertain arguments that a party asserts for the first time on appeal, ‘an argument is not [forfeit]ed on appeal if the argument on the issue before the district court was sufficient to permit the district court to rule on it.’ Here, CEATS told the district court that a discovery violation ‘must be committed willfully or in bad faith for the court to award the severest remedies available under Rule 37(b).’ CEATS also argued that it did not violate the Protective Order willfully or in bad faith, because the ‘communications … were clearly inadvertent.’ That argument was enough to put the district court on notice that CEATS opposed any definition of ‘bad faith’ that includes inadvertent conduct.”

CEATS, Inc. v. TicketNetwork, Inc., No. 21-40705 (June 19, 2023) (citations and footnotes omitted). (This analysis has an interesting analog in the recent case of United Natural Foods, Inc. v. NLRB, where the majority and dissent disputed whether a particular issue was raised for purposes of the “party presentation” principle).

In Norsworthy v. Houston ISD, the Fifth Circuit acknowledged a recent amendment to Fed. R. App. P. 3(c) about the requirements for a notice of appeal.

In this case, the appellant’s notice of appeal named its Rule 59 motion to alter amend, not the final judgment itself. Under the earlier rule, that language could have given rise to a waiver issue. But a 2021 amendment says that “a notice of appeal encompasses the final judgment,” so long as the notice designates an order named in Fed. R. App. P. 4(a)(4)(A), which lists the standard post-trial motions. No. 22-20586 (June 13, 2023).

In Ortiz v. Jordan, 562 U.S. 180 (2011), the Supreme Court “held that an order denying summary judgment on sufficiency of the evidence grounds is not apealable after a trial …. a party who wants to preserve a sufficiency challenge for appeal must raise it anew in a post-trial motion.”

In Dupree v. Younger, No. 22-210 (May 25, 2023): “The question presented in this case is whether this preservation requirement extends to a purely legal issue resolved at summary judgment. The answer is no.

That distinction makes sense and should help avoid unnecessary disputes about preservation. There will, however, be disputes about “sufficiency” questions that turn on points of law; as illustrated by the longstanding definition of a “no evidence” appeal issue in Texas state practice:

“No evidence” points must, and may only, be sustained when the record discloses one of the following situations: (a) a complete absence of evidence of a vital fact; (b) the court is barred by rules of law or of evidence from giving weight to the only evidence offered to prove a vital fact; (c) the evidence offered to prove a vital fact is no more than a mere scintilla; (d) the evidence establishes conclusively the opposite of the vital fact.

City of Keller v. Wilson, 168 S.W.3d 802 (Tex. 2005).

It was a busy week for legislative privilege; after an opinion involving the latest dispute about the Jackson airport, the Fifth Circuit again ruled in favor of legislative-privilege claims in LULAC v. Hughes. The Court held that such matters were appropriately raised by interlocutory appeal, and on the merits observed:

“The privilege log shows that the legislators did not send privileged documents to third parties outside the legislative process; instead they brought third parties into the process. That decision did not waive the privilege. The very fact that Plaintiffs need discovery to access these documents shows that they have not been shared publicly. On the other hand, if the legislators had shared the documents publicly, then they could not rely on the privilege to prevent Plaintiffs from introducing those documents as evidence. But here, where the documents have been shared with some third parties—but haven’t been shared publicly—the waiver argument fails.”

No. 22-50435 (May 17, 2023) (emphasis in original).

United Natural Foods, Inc. v. NLRB, No. a seemingly dry dispute about whether NLRB’s general counsel could withdraw an unfair labor practice complaint, produced a spirited clash between majority and dissent about how the “party presentation” principle applied to the arguments advanced in that case (see United States v. Sineneng-Smith, 140 S.Ct. 1575 (2020)). No. 21-60532 (April 24, 2023).

Despite that clash, all panel members agreed that simply throwing shade at Chevron was insufficient to present an issue for appellate review:

The Fifth Circuit recently summarized the sometimes-confusing law about when an adverse ruling about a grand-jury subpoena may be appealed:

The Fifth Circuit recently summarized the sometimes-confusing law about when an adverse ruling about a grand-jury subpoena may be appealed:

Our jurisdiction is generally limited to reviewing final decisions of a district court. This rule applies to appeals of orders issued in grand jury proceedings. There are two exceptions. First, if a witness chooses not to comply with a grand jury subpoena compelling production of documents and is held in contempt, that witness may immediately appeal the court’s interlocutory order. Second, under what is called the Perlman doctrine, a party need not be held in contempt prior to filing an interlocutory appeal if “the documents at issue are in the hands of a third party who has no independent interest in preserving their confidentiality.

In re Grand Jury Subpoena, No. 21-30705 (Dec. 14, 2022). (At least in theory, a mandamus petition may also be available in this setting, see generally David Coale, Five Years After Mohawk, 34 Rev. Litig. 1 (2015)).

iiiTec v. Weatherford Technology Holdings presents a series of unfortunate events that led to dismissal of an appeal.

iiiTec v. Weatherford Technology Holdings presents a series of unfortunate events that led to dismissal of an appeal.

- “iiiTec filed two motions on July 23, 2021, the twenty-eighth day after judgment. The first was a request to exceed the page limit on its proposed Rule 59/60 motion; the second was a short 14-page motion to alter the judgment. A request for leave to file is not one that can toll the deadline to appeal, but a motion to alter is.” (footnote omitted). So far, so good. But then …

- “[W]hen the court struck iiiTec’s motion to alter on October 4, the deadline to appeal reset to thirty days later on November 3. But by that date, iiiTec still had not filed its notice of appeal; it had only filed another Rule 59/60 motion to reconsider. Under Rule 59, the motion was untimely for exceeding the strict 28-day period to file; and under Rule 60, the motion could not toll the deadline because it was filed more than 28-days after final judgment.” (footnote omitted).

No. 22-20076 (Dec. 27, 2022, unpublished).

In Rhone v. City of Texas City, the Fifth Circuit denied a request for emergency relief without prejudice, first describing the controlling rules:

In Rhone v. City of Texas City, the Fifth Circuit denied a request for emergency relief without prejudice, first describing the controlling rules:

[Fed. R. App. P. ] 8(a)(1) states that “[a] party must ordinarily move first in the district court for … (A) a stay of the judgment or order of a district court pending appeal.” Rule 8(a)(2) provides, however that “[a] motion for the relief mentioned in Rule 8(a)(1) may be made to the court of appeals or to one of its judges.” That provision is subject to a requirement that “[t]he motion must: (i) show that moving first in the district court would be impracticable; or (ii) state that, a motion having been made, the district court denied the motion or failed to afford the relief requested and state any reasons given by the district court for its action.” Rule 8(a)(2)(A).

Applying those rules, the Court concluded:

In this case, Rhone has moved for relief from judgment in the district court and no ruling has been made. As such, this motion is premature. Therefore, the motion before us is denied without prejudice. Should the district court deny Rhone’s pending motion, Rhone may revive the motion in this Court.

No. 22-40551 (Sept. 19, 2022, unpublished).

A surprising amount of case law addresses not whether a particular legal conclusion is correct, but whether it is “correct enough”–qualified immunity, for example, as well as mandamus cases about whether a “clear error” occurred in applying the law. Another such area involves whether the Fifth or the Federal Circuit has appellate jurisdiction over “Walker Process cases”–antitrust claims based on enforcement of a fraudulent patent. In Chandler v. Phoenix Services LLC, the Fifth Circuit held:

A surprising amount of case law addresses not whether a particular legal conclusion is correct, but whether it is “correct enough”–qualified immunity, for example, as well as mandamus cases about whether a “clear error” occurred in applying the law. Another such area involves whether the Fifth or the Federal Circuit has appellate jurisdiction over “Walker Process cases”–antitrust claims based on enforcement of a fraudulent patent. In Chandler v. Phoenix Services LLC, the Fifth Circuit held:

“We differ with the Federal Circuit over whether we have appellate jurisdiction over Walker Process cases. But the Supreme Court has told us to accept circuit-to-circuit transfers if the jurisdictional question is ‘plausible.’ While we continue to disagree with the Federal Circuit on this point, we do not find the transfer implausible. We therefore accept the case and affirm the district court’s judgment.”

No. 21-10626 (Aug. 15, 2022) (citations omitted).

Sambrano v. United Airlines, a religious-discrimination case about an airline’s vaccine mandate that prompted a (literally) fiery dissent from the panel opinion, ended in a 13-4 vote against en banc review. A dissent again urged caution in the use of unpublished (and thus, nonprecedential) opinions in significant matters. No. 21-11159 (Aug. 18, 2022).

“A bench ruling can be effective without a written order and does trigger appeal deadlines if it is final—which this ruling was. While Guerra is right that the district court’s bench ruling did not comply with [Fed. R. Civ. P.] 58’s ‘separate document’ requirement, that neither prevented him from appealing nor gave him infinite time to appeal.” Ueckert v. Guerra, No. 22-40263 (June 27, 2022).

An interlocutory appeal had some matters entangled with it in Jiao v. Xu (not unlike the quantum entanglement recently photographed for the first time, right):

An interlocutory appeal had some matters entangled with it in Jiao v. Xu (not unlike the quantum entanglement recently photographed for the first time, right):

“The preliminary injunction is an interlocutory order made appealable by 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1). The declaratory relief constitutes a final order, and we have appellate jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 2201. The turnover order is likewise final, and we have appellate jurisdiction to review it under 28 U.S.C. § 1291. Typically, we would not have jurisdiction over the district court’s

denial of Xu’s motion to dismiss. But to the extent the

underpinnings of Xu’s motion are inextricably intertwined with the district court’s subsequent rulings challenged on appeal, we determine that we have jurisdiction to address those issues. See Magnolia Marine Transp. Co. v. Laplace Towing Corp., 964 F.2d 1571, 1580 (5th Cir. 1992) (‘[O]ur jurisdiction is not limited to the specific [injunctive] order appealed from, and we may review all matters which establish the immediate basis for granting injunctive relief.’); see also In re Lease Oil Antitrust Litig. (No. II), 200 F.3d 317, 320 (5th Cir. 2000) (reaching denial of motion to dismiss as part of § 1292(a)(1) appeal where issues were ‘so entangled as to arrive here together’ and ‘[d]elaying review . . . would make no practical sense’).”

No. 20-20106 (March 11, 2022) (emphasis added, footnote and certain citations omitted).

While expediting consideration of the merits, a Fifth Circuit panel declined to stay a national injunction against a vaccination requirement for federal employees; a detailed dissent would have granted an interim stay of the injunction. Feds for Medical Freedom v. Biden, No. 20-30090 (Feb. 11, 2022). A thorough (albeit, highly partisan) article about the case recently appeared in Slate.

While expediting consideration of the merits, a Fifth Circuit panel declined to stay a national injunction against a vaccination requirement for federal employees; a detailed dissent would have granted an interim stay of the injunction. Feds for Medical Freedom v. Biden, No. 20-30090 (Feb. 11, 2022). A thorough (albeit, highly partisan) article about the case recently appeared in Slate.

“Most of Sea Wasp’s appeal challenges the district court’s summary judgment rulings finding it liable under both federal and state law. Despite those rulings, however, the court ultimately entered a judgment ‘that Plaintiff takes nothing and that Plaintiff’s case against Defendant is DISMISSED WITH PREJUDICE.’ In other words, Sea Wasp won the war even if it lost some battles along the way. Because the final judgment was a full victory for Sea Wasp, it is not an aggrieved party entitled to bring a cross appeal.” Domain Protection LLC v. Sea Wasp, LLC, No. 20-40411 (Jan. 13, 2022) (emphasis added).

“Most of Sea Wasp’s appeal challenges the district court’s summary judgment rulings finding it liable under both federal and state law. Despite those rulings, however, the court ultimately entered a judgment ‘that Plaintiff takes nothing and that Plaintiff’s case against Defendant is DISMISSED WITH PREJUDICE.’ In other words, Sea Wasp won the war even if it lost some battles along the way. Because the final judgment was a full victory for Sea Wasp, it is not an aggrieved party entitled to bring a cross appeal.” Domain Protection LLC v. Sea Wasp, LLC, No. 20-40411 (Jan. 13, 2022) (emphasis added).

A footnote in June Medical Services v. Phillips detailed the Fifth Circuit’s procedures for documents sealed in the trial court.

A footnote in June Medical Services v. Phillips detailed the Fifth Circuit’s procedures for documents sealed in the trial court.

“When presented with an appeal, we routinely unseal documents that were sealed in the district court when those documents are used on appeal and there is no legal basis for sealing. Indeed, we often do this sua sponte. In [one recent case], he district court sealed parts of the record pursuant to a stipulated protective order ‘in an effort to accommodate the defendant’s concerns about its trade secrets becoming public.’ Notwithstanding the stipulated protective order in that case, this court denied the appellant’s unopposed motion to place record excerpts under seal and ordered that the record excerpts be unsealed. . Indeed, when parties in this court seek to file documents under seal on appeal, the clerk’s office sends them a standard letter that requires them to ‘explain in particularity the necessity for sealing in this court. Counsel do not satisfy this burden by simply stating that the originating court sealed the matter, as the circumstances that justified sealing in the originating court may have changed or may not apply in an appellate proceeding.””

No. 21-30001-CV (Jan. 7, 2022) (citations omitted).

In DeOtte v. State of Nevada, the district court’s injunction about the contraceptive mandate in the Affordable Care Act became moot after a 2020 Supreme Court opinion. The State of Nevada, a latecomer to the case, sought vacatur of the injunction.

The Fifth Circuit summarized the applicable principles. Its “authority to vacate comes from [28 U.S.C. § 2106] that provides that an appellate court ‘may affirm, modify, vacate, set aside or reverse any judgment, decree, or order of a court lawfully brought before it for review.'” (emphasis omitted). Under that statute:

“[V]acatur is not automatic; it is ‘equitable relief’ and must ‘take account of the public interest.’ Precedents ‘are not merely the property of private litigants and should stand unless a court concludes that the public interest would be served by a vacatur.’ A court must assess ‘the equities of the individual case’ to determine whether vacatur is proper. This consideration centers on (1) ‘whether the party seeking relief from the judgment below caused the mootness by voluntary action’; and (2) whether public interests support vacatur.”

(citations omitted). After a thorough review of Nevada’s unusual procedural position in the case, the Court found that Nevada had standing (in the language of the statute, had “lawfully brought” the appeal), and granted Nevada the requested relief of vacatur. No. 19-10754 (Dec. 17, 2021).

In a challenge to the constitutionality of the “eviction moratorium,” the federal government argued that the case had become moot because the specific order at issue had expired. The Fifth Circuit expressed skepticism:

“Appellees respond that the appeal is not moot because the parties still dispute whether the government has constitutional power under the Commerce Clause to invade individual property rights by limiting landlords’ use of state court eviction remedies. The government maintains it has such authority. And in the government’s view, espoused at oral argument, that constitutional power is in no way limited to combatting the ongoing pandemic; the government asserts it can wield that staggering constitutional authority for any reason. Appellees further contend the proposed dismissal is a pretext to avoid appellate review of the constitutional question.”

(emphasis added). The court concluded, however, that it did not need to address mootness because it was granting the government’s motion to dismiss “on terms . . . fixed by the court” under FRAP 42. Those terms included the “express condition” that ‘”our dismissal does not abrogate the district court’s judgment or opinion, both of which remain in full force according to the express concession of the government during oral argument and in briefing.” Terkel v. Centers for Disease Control, No. 21-40137 (Oct. 19, 2021) (One panelist joined the result only.)

Zurich won an insurance coverage dispute with Maxim Crane. On appeal, in addition to defending the merits, Zurich argued that the matter should be dismissed entirely because Maxim lacked standing. This argument led to the question whether a cross-appeal was needed to make that point, and the Fifth Circuit concluded:

… although our judgment would be different if we credited Zurich’s standing argument, that does not mean that Zurich needed to file a cross-appeal to present that argument. To be sure, as a matter of standard appellate practice, “[m]any cases state the general rule that a cross-appeal is required to support modification of the judgment,” whereas “arguments that support the judgment as entered can be made without a cross-appeal.” (quoting [Wright & Miller]). But this case falls within an exception to that general rule. A cross-appeal “is not necessary to challenge the subject-matter jurisdiction of the district court, under the well-established rule that both district court and appellate courts are obliged to raise such questions on their own initiative.” Id.

Maxim Crane Works LP v. Zurich Am. Ins. Co., No. 19-20489 (Aug. 20, 2021) (ultimately, certifying the underlying coverage issue to the Texas Supreme Court).

Official Committee of Unsecured Creditors v. Walker County Hosp. Dist. presented a debtor’s challenge to the terms of a bankruptcy court’s sale order. The Fifth Circuit dismissed: “In this opinion, we have held that § 363(m) forecloses the creditor’s appeal because it failed to seek the required stay of the Sale Order. Established precedent leads us to this conclusion, and the Committee’s argument that it appealed an order not subject to § 363(m) is unpersuasive. In short: no stay, no pay.” No. 20-20572 (July 12, 2021) (emphasis added).

Official Committee of Unsecured Creditors v. Walker County Hosp. Dist. presented a debtor’s challenge to the terms of a bankruptcy court’s sale order. The Fifth Circuit dismissed: “In this opinion, we have held that § 363(m) forecloses the creditor’s appeal because it failed to seek the required stay of the Sale Order. Established precedent leads us to this conclusion, and the Committee’s argument that it appealed an order not subject to § 363(m) is unpersuasive. In short: no stay, no pay.” No. 20-20572 (July 12, 2021) (emphasis added).

The Fifth Circuit granted a stay during appeal in a challenge to a Texas JP’s practices regarding an invocation at the beginning of court proceedings: “In deciding whether to grant a stay pending appeal, we consider four factors: ‘(1) whether the stay applicant has made a strong showing that he is likely to succeed on the merits; (2) whether the applicant will be irreparably injured absent a stay; (3) whether issuance of the stay will substantially injure the other parties interested in the proceeding; and (4) where the public interest lies.’ All four factors favor Judge Mack.” The Court found a “manifestly erroneous” analysis of Ex Parte Young by the district court, which guided the application of the remaining factors in the appellant’s favor. Freedom From Religion Foundation v. Mack, No. 21-20279 (July 9, 2021).

The Fifth Circuit granted a stay during appeal in a challenge to a Texas JP’s practices regarding an invocation at the beginning of court proceedings: “In deciding whether to grant a stay pending appeal, we consider four factors: ‘(1) whether the stay applicant has made a strong showing that he is likely to succeed on the merits; (2) whether the applicant will be irreparably injured absent a stay; (3) whether issuance of the stay will substantially injure the other parties interested in the proceeding; and (4) where the public interest lies.’ All four factors favor Judge Mack.” The Court found a “manifestly erroneous” analysis of Ex Parte Young by the district court, which guided the application of the remaining factors in the appellant’s favor. Freedom From Religion Foundation v. Mack, No. 21-20279 (July 9, 2021).

The Supreme Court affirmed the Fifth Circuit’s analysis of appellate costs (often a trivial issue, but here involving over $2 million in supersedeas-bond premiums) in City of San Antonio v. Hotels.com, stating: “[W]e hold that courts of appeals have the discretion to apportion all the appellate costs covered by Rule 39 and that district courts cannot alter that allocation.” No. 20–334 (U.S. May 27, 2021). (It remains to be seen how the Roberts Court will review other, more politically charged opinions from the Fifth Circuit this term.)

During the course of a long-running contract dispute, the Fifth Circuit remanded the case for further development of the record about diversity jurisdiction. Problems with appellate deadlines for a later appeal ensued; in reviewing the parties’ arguments the Court noted:

During the course of a long-running contract dispute, the Fifth Circuit remanded the case for further development of the record about diversity jurisdiction. Problems with appellate deadlines for a later appeal ensued; in reviewing the parties’ arguments the Court noted:

- “Full” v. “partial” remand. “It is true that in some cases where this court has remanded with a specific directive to the district court, we have retained jurisdiction over the appeal, obviating the need for the appellant to file a new notice of appeal after the district court’s remand proceedings. However, in those cases, this court specified that we retained jurisdiction over the appeal.”

- Effect of an attorneys-fee appeal. “[W]hen the merits judgment has already become final and unappealable, a mere delay of that judgment is no longer possible, and the court lacks any authority under FRAP 4(a)(4)(A)(iii) and FRCP 58[(e)] to modify the finality or the effect of the merits judgment.” (citation omitted).

- Good cause is not GOOD CAUSE. “Rule 4(a)(5), unlike Rule 4(a)(4)(A)(iii) and Rule 58(e), does allow a district court to revive an untimely notice of appeal after the original time to appeal has expired. … Pathway’s motion cannot be construed as a Rule 4(a)(5) motion, however. The extension motion cites Rule 58(e) rather than Rule 4(a)(5), and its arguments are relevant only to the former ….”

Midcap Media Finance LLC v. Pathway Data, Inc., No. 20-50259 (April 20, 2021).

While written in a criminal appeal, Judge Oldham’s recent concurrence about specificity in error preservation is of broad general interest; he concludes:

While written in a criminal appeal, Judge Oldham’s recent concurrence about specificity in error preservation is of broad general interest; he concludes:

“[A] general declaration of ‘insufficient evidence!’ is not a meaningful objection. It challenges no particular legal error. It identifies no particular factual deficiency. It does nothing to focus the district judge’s mind on anything. It’s the litigator’s equivalent of freeing the beagles in a field that might contain truffles. Cf. del Carpio Frescas, 932 F.3d at 331 (“Judges are not like pigs, hunting for truffles buried in the record.” (quotation omitted)). Rather, if the defendant wants to preserve an insufficient-evidence challenge for de novo review, he must make a proper motion under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 29 and ‘specify at trial the particular basis on which acquittal is sought so that the Government and district court are provided notice.'”

United States v. Kieffer, No. 19-30225-CR (March 19, 2021). Notes: (1) A big 600Camp thanks to Jeff Levinger for drawing my attention to this case, and (2) Judge Oldham correctly notes that beagles are superior to pigs for finding truffles, as pigs tend to eat the valuable truffles after locating them.

An unusual Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(5) proceeding did not create appellate jurisdiction: “This case does not yet involve a final determination of the status of the interpleaded funds. Instead, it involves Rule 60(b)(5) relief from a prior order to disburse funds. The district court was not disbursing funds to the other party, but merely ordering that they be returned to the court’s registry pending the outcome of the state court action on remand. As the district court said, there has been no decision on who is entitled to the money. The final judgment has been set aside. Thus, this court lacks jurisdiction to hear this appeal.” Reed Migraine Centers of Texas v. Chapman, No. 20-10156 (Jan. 28, 2021).

“Mindful of the fundamental right to fairness in every proceeding–both in fact, and in appearance,” the Fifth Circuit reversed the outcome in a Title VII dispute, and ordered the reassignment to a new district judge on remand, when:

“Mindful of the fundamental right to fairness in every proceeding–both in fact, and in appearance,” the Fifth Circuit reversed the outcome in a Title VII dispute, and ordered the reassignment to a new district judge on remand, when:

From the outset of these suits, the district judge’s actions evinced a prejudgment of Miller’s claims. At the beginning of the Initial Case Management Conference, the judge dismissed sua sponte Miller’s claims against TSUS and UHS, countenancing no discussion regarding the dismissal. Later in the same conference, the judge responded to the parties’ opposition to consolidating Miller’s two cases by telling Miller’s counsel, “I will get credit for closing two cases when I crush you. . . . How will that look on your record?”

And things went downhill from there. The court summarily denied Miller’s subsequent motion for reconsideration, denied Miller’s repeated requests for leave to take discovery (including depositions of material witnesses), and eventually granted summary judgment in favor of SHSU and UHD, dismissing all claims.”

Miller v. Sam Houston State, No. 19-20752 (Jan. 29, 2021).

The panel in Gonzalez v. CoreCivic, Inc., No. 19-50691 (Jan. 20, 2021), in the context of an interlocutory appeal certified under 28 USC § 1292, affirmed the denial of a motion to dismiss a claim based on the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000. That law imposes civil liability on on e who “knowingly provides or obtains the labor or services of a person” by certain coercive means. The panel found that the text of the statute unambiguously reached the plaintiffs’ claims against a private company that operated detention facilities for ICE.

A dissent would have found that the plaintiff did not adequately state her claim under Twombly and Iqbal; in response, a concurrence argued that the concept of “party presentation” foreclosed the Court’s review of that matter. North Texas practitioners will recognize echoes of the debate among Justices about supplemental briefing from the Flakes litigation.

Did that recent SCOTUS opinion overrule older Circuit authority? “If a

precedent of this Court has direct application in a case, yet appears to rest on

reasons rejected in some other line of decisions, the Court of Appeals should

follow the case which directly controls, leaving to this Court the prerogative

of overruling its own decisions.” Baisley v. Int’l Assoc. of Machinists & Aerospace Workers, No. 20-50319 (Dec. 22, 2020) (quoting Rodriguez de Quijas v. Shearson/American Express, Inc., 490 U.S. 477, 484 (1989)).

“When Amazon allows third parties to sell products on its website, is Amazon ‘placing’ products into the stream of commerce or merely ‘facilitating’ the stream? If the former, then Amazon is a ‘seller’ under Texas products-liability law and potentially liable for injuries caused by unsafe products sold on its website. But if Amazon only facilitates the stream when it hosts third-party vendors on its platform, then it is not a seller, meaning injured consumers cannot sue for alleged product defects.” The Fifth Circuit certified this important issue to the Texas Supreme Court in McMillian v. Amazon, No. 20-20108 (Dec. 18, 2020).

Practice tip: In the Court’s review of whether the issue warranted certification, it noted that both parties had agreed that there was “substantial ground for difference of opinion” in order to proceed with an interlocutory appeal under 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b).

Automation Support, Inc. v. Philippi, No. 20-10386 (Dec. 8, 2020).

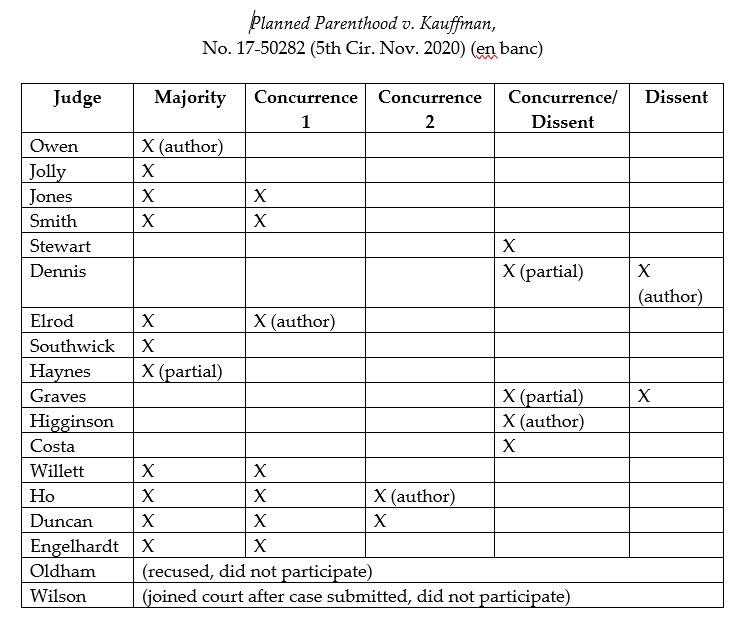

The dry-sounding issue before the en banc court in Planned Parenthood v. Kauffman, No. 17-50282 (Nov. 23, 2020), was “whether 42 U.S.C. § 1396a(a)(23) gives Medicaid patients a right to challenge, under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, a State’s determination that a health care provider is not ‘qualified’ within the meaning of § 1396a(a)(23).” The practical consequence of that issue, however, is significant–who may sue about Texas’s termination of several Planned Parenthood facilities from that state’s Medicaid program.

The majority held that under a 1980 Supreme Court case and the structure of the statute, the patients did not have the right to sue. In so doing, the Fifth Circuit joined the Eighth Circuit and split with five others. A 7-judge concurrence (2 votes shy of a majority, given the configuration of the en banc court for this case) would have reached the merits and rejected them. The opinions are illustrated in the chart below:

Richardson v. Flores reviewed the standards for intervention into an ongoing appeal, noting: “There is no appellate rule allowing intervention generally. Instead, the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure contemplate intervention only in

Richardson v. Flores reviewed the standards for intervention into an ongoing appeal, noting: “There is no appellate rule allowing intervention generally. Instead, the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure contemplate intervention only in

proceedings to review agency action. Fed. R. App. P. 15(d). But despite the lack of an on-point rule, we have allowed intervention in cases outside the scope of Rule 15(d). . . . Perhaps because there is no rule explicitly allowing intervention on appeal, the caselaw explicating the standards for such motions is scarce. In Bursey, when granting a similar motion to intervene, we said ‘a court of appeals may,  but only in an exceptional case for imperative reasons, permit intervention where none was sought in the district court.'” (footnote and citations omitted, emphasis in original). The Court also noted: “Motions to intervene on appeal are different from motions to intervene for purposes of appeal. Motions to intervene for purposes of appeal are used where ‘the existing parties have decided not to pursue [an appeal]’ and are filed in district courts in the first instance under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.” (citation omitted).

but only in an exceptional case for imperative reasons, permit intervention where none was sought in the district court.'” (footnote and citations omitted, emphasis in original). The Court also noted: “Motions to intervene on appeal are different from motions to intervene for purposes of appeal. Motions to intervene for purposes of appeal are used where ‘the existing parties have decided not to pursue [an appeal]’ and are filed in district courts in the first instance under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.” (citation omitted).

In one of many recent election-law disputes, the panel majority in Richardson v. Hughs painstakingly reviewed, and rejected, the plaintiffs’ challenge to Texas’s practices about signature verification for mail-in ballots. The procedural posture was a motion to stay; a concurrence cauti

In one of many recent election-law disputes, the panel majority in Richardson v. Hughs painstakingly reviewed, and rejected, the plaintiffs’ challenge to Texas’s practices about signature verification for mail-in ballots. The procedural posture was a motion to stay; a concurrence cauti oned: “[T]he reality is that the ultimate legality of the present system cannot be settled by the federal courts at this juncture when voting is already underway, and any opinion on a motions panel is essentially written in sand with no precedential value ….” footnote omitted). No. 20-50774 (Oct. 20, 2020).

oned: “[T]he reality is that the ultimate legality of the present system cannot be settled by the federal courts at this juncture when voting is already underway, and any opinion on a motions panel is essentially written in sand with no precedential value ….” footnote omitted). No. 20-50774 (Oct. 20, 2020).

A challenging case about the Texas foster-care system returned to the Fifth Circuit in M.D. v. Abbott, No. 19-41015 (Oct. 16, 2020), and the panel did not approve of revisions to an injunction that went beyond its mandate in the previous appeal: “Plaintiffs claim that the district court did not violate the mandate rule

A challenging case about the Texas foster-care system returned to the Fifth Circuit in M.D. v. Abbott, No. 19-41015 (Oct. 16, 2020), and the panel did not approve of revisions to an injunction that went beyond its mandate in the previous appeal: “Plaintiffs claim that the district court did not violate the mandate rule

because a court ‘invok[ing] equity’s power to remedy a constitutional

violation by an injunction mandating systemic changes to an institution’ generally has ‘the continuing duty and responsibility to assess the efficacy and consequences of its order.’ As Plaintiffs point out, we recited this general principle in Stukenberg II,  stating that ‘[a] district court undoubtedly has the equitable power to oversee compliance with its own injunction.’ ‘E]quitable decrees that impose a continuing supervisory function on the court commonly . . . contemplate the subsequent issuance of specific implementing injunctions.’ But judges disagree on occasion over the proper exercise of equitable powers, just as judges disagree on occasion over the proper interpretation o statutes. When that happens, appellate courts must make the final decision—and once the decision is made, it must be followed. And that, of course, is the whole purpose of the mandate rule: ‘A district court on remand . . . may not disregard the explicit directives of [the appellate] court'”.’ A (citations omitted).

stating that ‘[a] district court undoubtedly has the equitable power to oversee compliance with its own injunction.’ ‘E]quitable decrees that impose a continuing supervisory function on the court commonly . . . contemplate the subsequent issuance of specific implementing injunctions.’ But judges disagree on occasion over the proper exercise of equitable powers, just as judges disagree on occasion over the proper interpretation o statutes. When that happens, appellate courts must make the final decision—and once the decision is made, it must be followed. And that, of course, is the whole purpose of the mandate rule: ‘A district court on remand . . . may not disregard the explicit directives of [the appellate] court'”.’ A (citations omitted).

Early voting begins today in Texas. The Fifth Circuit stayed the district court’s order that would have let large Texas counties have more than one early-ballot pickup location. The panel majority concluded, inter alia, that the plaintiffs misconstrued the entirety of the Governor’s actions: “The July 27 and October 1 Proclamations—which must be read together to make sense—are beyond any doubt measures that ‘make[] it easier’ for eligible Texans to vote absentee. How this expansion of voting opportunities burdens anyone’s right to vote is a mystery” (citation omitted). From there, the majority concluded that the plaintiffs overstated the claimed burden, and failed to give sufficient weight to the Governor’s asserted interest in preventing voter fraud. A concurrence criticized the Governor’s use of emergency power: “If a governor can unilaterally suspend early voting laws to reach policy outcomes that you prefer, it stands to reason that a governor can also unilaterally suspend other election laws to achieve policies that you oppose.” Texas LULAC v. Hughs, No. 20-50867 (Oct. 12, 2020).

Early voting begins today in Texas. The Fifth Circuit stayed the district court’s order that would have let large Texas counties have more than one early-ballot pickup location. The panel majority concluded, inter alia, that the plaintiffs misconstrued the entirety of the Governor’s actions: “The July 27 and October 1 Proclamations—which must be read together to make sense—are beyond any doubt measures that ‘make[] it easier’ for eligible Texans to vote absentee. How this expansion of voting opportunities burdens anyone’s right to vote is a mystery” (citation omitted). From there, the majority concluded that the plaintiffs overstated the claimed burden, and failed to give sufficient weight to the Governor’s asserted interest in preventing voter fraud. A concurrence criticized the Governor’s use of emergency power: “If a governor can unilaterally suspend early voting laws to reach policy outcomes that you prefer, it stands to reason that a governor can also unilaterally suspend other election laws to achieve policies that you oppose.” Texas LULAC v. Hughs, No. 20-50867 (Oct. 12, 2020).

Certain motions toll the deadline for filing a notice of appeal — but not multiple times: “Here, the Employees filed a motion for judgment as a matter of law and, alternatively, a new trial, on March 12, 2019. The district court entered final judgment on March 27 without expressly addressing that motion, thus implicitly denying it. On April 10, the Employees refiled the motion. The refiled version was identical to the March 12 version that the judgment implicitly denied. It therefore did not toll the appeal deadline and the 30 days began to run with the entry of judgment on March 27. The Employees did not file a notice of appeal until June 12. Because that notice was untimely under 28 U.S.C. § 2107, the Employees’ appeal must be dismissed for lack of jurisdiction.” Edwards v 4JLJ, LLC, No. 19-40553 (Sept. 21, 2020) (on rehearing, footnotes omitted).

Certain motions toll the deadline for filing a notice of appeal — but not multiple times: “Here, the Employees filed a motion for judgment as a matter of law and, alternatively, a new trial, on March 12, 2019. The district court entered final judgment on March 27 without expressly addressing that motion, thus implicitly denying it. On April 10, the Employees refiled the motion. The refiled version was identical to the March 12 version that the judgment implicitly denied. It therefore did not toll the appeal deadline and the 30 days began to run with the entry of judgment on March 27. The Employees did not file a notice of appeal until June 12. Because that notice was untimely under 28 U.S.C. § 2107, the Employees’ appeal must be dismissed for lack of jurisdiction.” Edwards v 4JLJ, LLC, No. 19-40553 (Sept. 21, 2020) (on rehearing, footnotes omitted).

Many opinions address briefing waiver issues by an appellant. But what about an appellee? The Fifth Circuit examined that procedural point in Texas Democratic Party v. Abbott:

Many opinions address briefing waiver issues by an appellant. But what about an appellee? The Fifth Circuit examined that procedural point in Texas Democratic Party v. Abbott:

“Appellate rules regarding how we treat absent issues differ depending on whether it is the appellant or the appellee who has neglected them. An appellant can intentionally waive or inadvertently forfeit the right to present an argument by failure to press it on appeal, a higher threshold than simply mentioning the issue. On the other hand, even an appellee’s failure to file a brief does not cause an automatic reversal of the judgment being appealed. By appellate rule, so extreme a lapse does cause the appellee to lose the right to appear at oral argument. Fed. R. App. P. 31(c). We also know that if we disagree with the grounds relied upon by a district court to enter judgment but discover another fully supported by the record, we can affirm on that alternative basis. . . . There are a few cases that consider rules of waiver even for appellees. For example, our discretion to consider an argument not properly presented is ‘more leniently [applied] when the party who fails to brief an issue is the appellee.'”

No. 20-50407 (Sept. 10, 2020).

Earlier this month, the Fifth Circuit found an abuse of discretion, under Texas substantive law, in not modifying a noncompetition agreement at the preliminary-injunction stage. Calhoun v. Jack Doheny Cos., Inc. But because the parties had settled their case in the meantime, notifying the district court but not the Fifth Circuit, the case had become moot at the time of that opinion, prompting the Court to withdraw its opinion and dismiss the matter with prejudice. No. 20-20068 (Aug. 28, 2020).

Earlier this month, the Fifth Circuit found an abuse of discretion, under Texas substantive law, in not modifying a noncompetition agreement at the preliminary-injunction stage. Calhoun v. Jack Doheny Cos., Inc. But because the parties had settled their case in the meantime, notifying the district court but not the Fifth Circuit, the case had become moot at the time of that opinion, prompting the Court to withdraw its opinion and dismiss the matter with prejudice. No. 20-20068 (Aug. 28, 2020).

(This activity about a case named Calhoun prompted me to check in on the M/V CALHOUN, a ship that under another name created a memorable mootness argument– “The ship has sailed!” – when it left the Fifth Circuit before creditors could seize it. The ship continues to be elsewhere, arriving in Venezuela as of the date of this post.)

(This activity about a case named Calhoun prompted me to check in on the M/V CALHOUN, a ship that under another name created a memorable mootness argument– “The ship has sailed!” – when it left the Fifth Circuit before creditors could seize it. The ship continues to be elsewhere, arriving in Venezuela as of the date of this post.)

“The Texas Supreme Court has held that a Texas court of civil appeals does not have jurisdiction to initiate an award of appellate attorneys’ fees because ‘the award of any attorney fee is a fact issue which must [first] be passed upon the trial court.’” In Texas state courts, requesting appellate fees at the original trial is a placeholder requirement to ensure the state trial courts maintain jurisdiction over the issue. Those are procedural rules that do not apply in federal court. Our local rules provide for appellate litigants to petition this court for. Local Rule 47.8 does not require a party seeking appellate attorneys’ fees to first request appellate attorneys’ fees in the district court as a placeholder.” Atom Instrument Corp. v. Petroleum Analyzer Co., No. 19-20151 (Aug. 7, 2020) (citations omitted).

“The Texas Supreme Court has held that a Texas court of civil appeals does not have jurisdiction to initiate an award of appellate attorneys’ fees because ‘the award of any attorney fee is a fact issue which must [first] be passed upon the trial court.’” In Texas state courts, requesting appellate fees at the original trial is a placeholder requirement to ensure the state trial courts maintain jurisdiction over the issue. Those are procedural rules that do not apply in federal court. Our local rules provide for appellate litigants to petition this court for. Local Rule 47.8 does not require a party seeking appellate attorneys’ fees to first request appellate attorneys’ fees in the district court as a placeholder.” Atom Instrument Corp. v. Petroleum Analyzer Co., No. 19-20151 (Aug. 7, 2020) (citations omitted).

The trap: “The Funds sought to render an interlocutory decision appealable by dismissing at least one defendant without prejudice. And under [Williams v. Seidenbach, 958 F.3d 341, 369 (5th Cir. 2020) (en banc)], that means—absent some further act like a Rule 54(b) certification—there is no final, appealable decision.”

The trap: “The Funds sought to render an interlocutory decision appealable by dismissing at least one defendant without prejudice. And under [Williams v. Seidenbach, 958 F.3d 341, 369 (5th Cir. 2020) (en banc)], that means—absent some further act like a Rule 54(b) certification—there is no final, appealable decision.”

The hint: “Because the dismissal without prejudice in this case occurred after the order the Funds seek to appeal, we do not decide how Williams . . . would apply where the dismissal occurred before the adverse, interlocutory order. See Schoenfeld v. Babbitt 168 F.3d 1257, 1265–66 (11th Cir. 1999) (concluding that there was a final decision in such a case).”

The hint: “Because the dismissal without prejudice in this case occurred after the order the Funds seek to appeal, we do not decide how Williams . . . would apply where the dismissal occurred before the adverse, interlocutory order. See Schoenfeld v. Babbitt 168 F.3d 1257, 1265–66 (11th Cir. 1999) (concluding that there was a final decision in such a case).”

Firefighters’ Retirement System v. Citco Group Ltd., No. 19-30165 (July 7, 2020).

In long-running litigation about liability for hotel occupancy taxes, the Fifth Circuit’s prior mandate said that “plaintiff-appellee cross-appellant pay to defendants-appellants cross appellees the costs on appeal to be taxed by the Clerk of this Court.” The Court held that this language did not preclude the trial court clerk from assessing appropriate costs on remand pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 39(e).

In long-running litigation about liability for hotel occupancy taxes, the Fifth Circuit’s prior mandate said that “plaintiff-appellee cross-appellant pay to defendants-appellants cross appellees the costs on appeal to be taxed by the Clerk of this Court.” The Court held that this language did not preclude the trial court clerk from assessing appropriate costs on remand pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 39(e).

The Court also held: “The fact that the decretal language in the first appeal used the word ‘vacated’ instead of ‘reversed’ does not change this result. . . . While an argument can be made that ‘reversed’ might have been the better choice for the decretal language in the first appeal, what matters for purposes of Rule 39(a) is the substance of the disposition, not merely the form.” San Antonio v. Hotels.com, No. 19-50701 (May 11, 2020) (citations omitted, emphasis in original).

PRACTICE TIP: Fed. R. App. P. 39(e)(3) includes “premiums paid for a bond or other security to preserve rights pending appeal” as a taxable cost–in this litigation, a cost exceeding $2 million.

In affirming a preliminary injunction in a noncompete case, Realogy Holdings Corp. v. Jongeblood suggested that the district court could “when determining the term of any injunction, to reweigh the equities . . . in light of the time that has passed during the pendency of th[e] appeal.” Interestingly, this suggestion came after the Fifth Circuit had granted a stay during the preliminary-injunction appeal, which it also expedited. Specifically, the relevant covenants last for a year, the injunction was granted on November 15, 2019; the appellate stay was granted on January 24, 2020, and the opinion issued on April 27. No. 19-20864.

In affirming a preliminary injunction in a noncompete case, Realogy Holdings Corp. v. Jongeblood suggested that the district court could “when determining the term of any injunction, to reweigh the equities . . . in light of the time that has passed during the pendency of th[e] appeal.” Interestingly, this suggestion came after the Fifth Circuit had granted a stay during the preliminary-injunction appeal, which it also expedited. Specifically, the relevant covenants last for a year, the injunction was granted on November 15, 2019; the appellate stay was granted on January 24, 2020, and the opinion issued on April 27. No. 19-20864.

Gonzales cited two Texas Supreme Court cases, decided after a summary judgment against her, holding that an insurer’s payment of an appraisal award does not preclude a Texas Prompt Payment of Claims Act (“TPPCA”) claim. The Fifth Circuit found that she failed to preserve this argument in the district court. The Court noted that “a change in law . . . does not permit a party to raise an entirely new argument that could have been articulated below”–a rule that applies when a party “could have made the same ‘general argument’ to the district court, but had not done so.” As for the state of the law at the time of the summary-judgment briefing, the Court observed:

Gonzales cited two Texas Supreme Court cases, decided after a summary judgment against her, holding that an insurer’s payment of an appraisal award does not preclude a Texas Prompt Payment of Claims Act (“TPPCA”) claim. The Fifth Circuit found that she failed to preserve this argument in the district court. The Court noted that “a change in law . . . does not permit a party to raise an entirely new argument that could have been articulated below”–a rule that applies when a party “could have made the same ‘general argument’ to the district court, but had not done so.” As for the state of the law at the time of the summary-judgment briefing, the Court observed:

We recognize that several courts, including our own, had previously concluded a TPPCA claim was extinguished as a matter of law after the payment of an appraisal award. But the Supreme Court of Texas granted review in [the two relevant cases] on January 18, 2019, seven days after Allstate moved for summary judgment and thirteen days before Gonzales filed her response to the motion. This fact undermines her assertion here that she “could not have made a good faith argument in the trial court that payment of the appraisal award did not preclude her from recovering under the TPPCA as a matter of law.”

Gonzales v. Allstate Vehicle & Property Ins. Co., No. 19-40250 (Feb. 11, 2020) (emphasis added, footnote omitted).

Appellants complained about the treatment of their claims by the system established to resolve the “Chinese-Manufactured Drywall Products Liability Multi-District Litigation.” They contended that “a disagreement with the District Court’s interpretation and application of the settlement agreement invalidates the waivers” of appeal rights in that agreement. The Fifth Circuit disagreed, concluding that this argument “negates the entire purpose of the appeal waiver and would render these agreed upon terms meaningless,” and reminding that to make such a waiver, “a party need only understand the right to appeal that is given up, not all the facts relating to all potential challenges that could be raised on appeal.” Asch v. Gebrueder Knauf, No. 18-31223 (Dec. 12, 2019, unpublished).

Appellants complained about the treatment of their claims by the system established to resolve the “Chinese-Manufactured Drywall Products Liability Multi-District Litigation.” They contended that “a disagreement with the District Court’s interpretation and application of the settlement agreement invalidates the waivers” of appeal rights in that agreement. The Fifth Circuit disagreed, concluding that this argument “negates the entire purpose of the appeal waiver and would render these agreed upon terms meaningless,” and reminding that to make such a waiver, “a party need only understand the right to appeal that is given up, not all the facts relating to all potential challenges that could be raised on appeal.” Asch v. Gebrueder Knauf, No. 18-31223 (Dec. 12, 2019, unpublished).

“Here, however, we have an appeal from grant of a motion to dismiss without prejudice to refile. It is not a final judgment because ‘the district court did not adjudicate or dispose of any substantive issues on the merits.'” The King-Morocco v. Banner of N.O., L.L.C., No. 19-30323 (Nov. 27, 2019) (unpubl.) (citations omitted).

“Here, however, we have an appeal from grant of a motion to dismiss without prejudice to refile. It is not a final judgment because ‘the district court did not adjudicate or dispose of any substantive issues on the merits.'” The King-Morocco v. Banner of N.O., L.L.C., No. 19-30323 (Nov. 27, 2019) (unpubl.) (citations omitted).

Diece-Lisa Indus., Inc. v. Disney Enterprises, Inc., a dispute about trademark rights related to “Lots-O’-Huggin’ Bear” (right), analyzed whether the disposition of several consolidated cases on personal-jurisdiction grounds could be reviewed. After reviewing the specific claims and the applicable standards, the Fifth Circuit “conclude[d] that we have jurisdiction to review the interlocutory orders . . . because they can be ‘regarded as merged into the final judgment terminating'” one of the case numbers. It then affirmed, finding that the plaintiffs’ “franchise theory” (a kind of single-business-enterprise argument) lacked merit, and that a nonexclusive license agreement also was not, by itself, a basis for jurisdiction. No. 17-41268 (Nov. 19, 2019).

Diece-Lisa Indus., Inc. v. Disney Enterprises, Inc., a dispute about trademark rights related to “Lots-O’-Huggin’ Bear” (right), analyzed whether the disposition of several consolidated cases on personal-jurisdiction grounds could be reviewed. After reviewing the specific claims and the applicable standards, the Fifth Circuit “conclude[d] that we have jurisdiction to review the interlocutory orders . . . because they can be ‘regarded as merged into the final judgment terminating'” one of the case numbers. It then affirmed, finding that the plaintiffs’ “franchise theory” (a kind of single-business-enterprise argument) lacked merit, and that a nonexclusive license agreement also was not, by itself, a basis for jurisdiction. No. 17-41268 (Nov. 19, 2019).

In Williams v. TH Healthcare Ltd., No. 19-20134 (Nov. 14, 2019, unpubl.), the Fifth Circuit made two broadly-applicable points about the deadline running from receipt of an EEOC right-to-sue letter:

In Williams v. TH Healthcare Ltd., No. 19-20134 (Nov. 14, 2019, unpubl.), the Fifth Circuit made two broadly-applicable points about the deadline running from receipt of an EEOC right-to-sue letter:

- Extra days for the weekend. Williams received a right-to-sue letter for her Title VII and ADA claims on July 29, 2018. The ninety-day deadline for filing suit fell on Saturday, October 27, 2018. Williams thus had until the following Monday, October 29, 2018, to file suit. Williams filed suit that day. Her lawsuit was therefore timely and the district court erred in dismissing it.

- Substantive, but not jurisdictional. “he district court concluded that it “d[id] not have jurisdiction over Dovie Williams’s claims because she did not sue within ninety days of receiving the [right-to-sue] letter.” The ninety-day filing requirement, however, “is not a jurisdictional prerequisite, but more akin to a statute of limitations.” Harris v. Boyd Tunica, Inc., 628 F.3d 237, 239 (5th Cir. 2010). The court therefore treats the district court’s order as a dismissal of Williams’s claims pursuant to Rule 12(b)(6) for failing to comply with the ninety-day filing requirement.

“Since the issue of whether the district court applied the correct state’s law to resolve the matters before it is of primary importance in determining whether the district court ultimately reached the correct result in granting Gray’s request for summary judgment, we reject Gray’s categorization of its appeal as ‘conditional.’ Either the district court applied the correct law, or it did not. Whether the district court applied the correct law cannot and does not revolve on whether it reached a result that benefits Gray. Thus, we will address the propriety of the district court’s decision to apply Texas law regardless of whether we agree with the court’s conclusion under Texas law.” Aggreko LLC v. Chartis Specialty Ins. Co., No. 18-40325 (Nov. 11, 2019).

“Since the issue of whether the district court applied the correct state’s law to resolve the matters before it is of primary importance in determining whether the district court ultimately reached the correct result in granting Gray’s request for summary judgment, we reject Gray’s categorization of its appeal as ‘conditional.’ Either the district court applied the correct law, or it did not. Whether the district court applied the correct law cannot and does not revolve on whether it reached a result that benefits Gray. Thus, we will address the propriety of the district court’s decision to apply Texas law regardless of whether we agree with the court’s conclusion under Texas law.” Aggreko LLC v. Chartis Specialty Ins. Co., No. 18-40325 (Nov. 11, 2019).

The en banc Fifth Circuit will consider the panel opinion in Williams v. Taylor-Seidenbach, Inc., No. 18-31159 (Aug. 15, 2019), which continued to find a lack of appellate jurisdiction over a dispute because of the so-called “finality trap.” In a previous appeal, the Court found a lack of appellate jurisdiction over an order after three defendants had been dismissed without prejudice. The plaintiff returned to district

The en banc Fifth Circuit will consider the panel opinion in Williams v. Taylor-Seidenbach, Inc., No. 18-31159 (Aug. 15, 2019), which continued to find a lack of appellate jurisdiction over a dispute because of the so-called “finality trap.” In a previous appeal, the Court found a lack of appellate jurisdiction over an order after three defendants had been dismissed without prejudice. The plaintiff returned to district  court and obtained a new order directing dismissal with prejudice (with some caveats), but to no avail: “[T]he rule 54(b) judgment did not retroactively transform the prior without-prejudice dismissals into with-prejudice dismissals. . . . [T]he finality trap, which was found to bar appellate jurisdiction in Williams I, remains shut.” Judge Haynes’s concurrence in the panel opinion asked for en banc review of the Fifth Circuit’s cases on this topic.

court and obtained a new order directing dismissal with prejudice (with some caveats), but to no avail: “[T]he rule 54(b) judgment did not retroactively transform the prior without-prejudice dismissals into with-prejudice dismissals. . . . [T]he finality trap, which was found to bar appellate jurisdiction in Williams I, remains shut.” Judge Haynes’s concurrence in the panel opinion asked for en banc review of the Fifth Circuit’s cases on this topic.

“This case is a perfect example of when we should certify cases, and why certification is valuable. We are presented with a question of pure statutory interpretation on a recurring issue of interest to citizens and businesses across Texas. What’s more, it is a question that divided judges on this court. As reflected in our competing concurring opinions, different judges on this court have disagreed about whether the district court correctly interpreted the Texas Sales Representative Act (“TSRA”). But we all agreed that reasonable minds could differ. So rather than provide a partial answer—binding only litigants who file in federal court, not those in state court— we instead certified the question to the Supreme Court of Texas, which can speak with authority for all litigants, in state and federal court alike. We now have that answer, and accordingly affirm in part and reverse and remand in part.” JCB Inc. v. Horsburgh & Scott Co., No. 17-51023 (Oct. 17, 2019).

“This case is a perfect example of when we should certify cases, and why certification is valuable. We are presented with a question of pure statutory interpretation on a recurring issue of interest to citizens and businesses across Texas. What’s more, it is a question that divided judges on this court. As reflected in our competing concurring opinions, different judges on this court have disagreed about whether the district court correctly interpreted the Texas Sales Representative Act (“TSRA”). But we all agreed that reasonable minds could differ. So rather than provide a partial answer—binding only litigants who file in federal court, not those in state court— we instead certified the question to the Supreme Court of Texas, which can speak with authority for all litigants, in state and federal court alike. We now have that answer, and accordingly affirm in part and reverse and remand in part.” JCB Inc. v. Horsburgh & Scott Co., No. 17-51023 (Oct. 17, 2019).