I am speaking at the Texas State Bar’s “Civil Appellate Practice 101” course on September 6 in Austin about key differences in procedural issues between Texas courts and federal courts in the Fifth Circuit. Here is a copy of the PowerPoint that I am using.

I am speaking at the Texas State Bar’s “Civil Appellate Practice 101” course on September 6 in Austin about key differences in procedural issues between Texas courts and federal courts in the Fifth Circuit. Here is a copy of the PowerPoint that I am using.

The high-stakes mandamus petition in In re DuPuy Orthopaedics, Inc., No. 17-10812 (Aug. 31, 2017), sought relief from an upcoming set of “bellweather” trials in a massive MDL proceeding about allegedly defective hip implants. After an hour-long oral argument – and despite Hurricane Harvey’s enormous impact on Houston, where all three panelists are based – the panel denied the petition a week after argument in an unusual “split decision.”

The high-stakes mandamus petition in In re DuPuy Orthopaedics, Inc., No. 17-10812 (Aug. 31, 2017), sought relief from an upcoming set of “bellweather” trials in a massive MDL proceeding about allegedly defective hip implants. After an hour-long oral argument – and despite Hurricane Harvey’s enormous impact on Houston, where all three panelists are based – the panel denied the petition a week after argument in an unusual “split decision.”

As to the underlying substantive issue – whether the trials could proceed despite strong arguments about personal jurisdiction – two of the three panelists (Judges Smith and Jones) found that a clear error had been committed. But as to mandamus relief, two of the three panelists (Judges Smith and Costa) concluded that the defendants had an adequate remedy by direct appeal.

The opinion has four implications for mandamus practice in the Fifth Circuit, generally.

First, Judge Costa now has a “track record” about mandamus petitions, and his observations in this case – consistent with his prior experience as a trial judge – suggest he has a restrictive view about its availability.

Second, if there was any doubt that mandamus is essentially limited to forum-selection disputes in the Fifth Circuit, the analysis of “adequate remedy” by the panel majority on that point should eliminate it. The unusual length and expense of the upcoming trial, coupled with its potential impact on settlement discussions for the entire MDL, was seen as the type of litigation expense and “hardship [that] may result from delay” that will not justify a mandamus petition.

Third, by detailing a panel majority’s view that the trial court had erred, the opinion continues a practice of offering something of an “advisory opinion” about the merits, despite declining to issue the writ. Indeed, footnote 4 of the opinion gives several examples of other opinions that have done so; two other recent examples include the opinions in In re: Crystal Power Co., 641 F.3d 82 (5th Cir. 2011) (“We confess puzzlement over why respondents insist on litigating this case in federal court even though . . . any judgment issued by the district court will su ely be reversed . . . . “) and In re: Trinity Industries, No. 14-41067 (Oct. 10, 2014) (“The court is compelled to note, however, that this is a close case.”)

Fourth, the opinion highlights the difference between federal and Texas state mandamus practice, despite the nominally similar tests used by the two court systems. A leading Texas Supreme Court case about the adequacy of appellate remedy observes: “Although this Court has tried to give more concrete direction for determining the availability of mandamus review, rigid rules are necessarily inconsistent with the flexibility that is the remedy’s principal virtue.” In re: Prudential Ins. Co., 148 S.W.3d 124 (Tex. 2004). The DuPuy panel majority has a different view of the point.

Five Tips for Hurricane Harvey Litigation (a version of this article is in this week’s Texas Lawbook)

In the course of reviewing the Fifth Circuit’s commercial cases for this blog, I have read many opinons about disputes arising from Hurricane Katrina cases. In light of the havoc recently created by Hurricane Harvey, I wanted to share five observations to prepare for the litigation that will inevitably result.

- Record the facts.

Any lawsuit creates tension between the past and the future. The parties want to move on, and put the expense and stress of litigation behind them. But the legal case forces them to revisit the past.

That tension is particularly acute after a disaster such as Harvey, which forced people and businesses to endure incredible stress, while making them then revisit that trauma to protect their legal rights in court. The – entirely understandable – desire to move on, must be squared with the need to take the time to preserve evidence.

Consider St. Bernard Parish v. Lafarge North America, a case about the destruction of a bridge during Hurricane Katrina. While the parties offered extensive expert testimony about what caused the damage, the summary judgment proceedings turned in no small part on the facts of what happened during the storm, including facts established by photographs.

A party facing litigation should consider – as awkward as it can be while recovering from a life-disrupting event – what facts seem obvious now but may fade from memory as time goes on. To the extent possible, some thought should be given to:

- maintaining electronic records, even if the hardware appears damaged at first blush;

- writing down a “log” of relevant conversations and events about important events;

- storing any relevant physical objects, for potential future analysis by experts; and

- simply writing down basic information about names, addresses, phone numbers, and the like.

In a case arising from a natural disaster, courts will likely be forgiving as to claims of spoliation. But lost information is lost, and its absence can later effect the resolution of a legal case.

- Help the people.

The fact evidence in the Lafarge case also included eyewitness testimony, which proved critical to defeating the defendant’s summary judgment motion. Just as a photograph can deteriorate, a person’s memory can fade. And the likelihood of that occurring can only increase when the person is placed under the severe stress of a natural disaster.

Any “team” confronted with a legal challenge by Harvey – a business, a professional organization, or even a family – should be mindful of the psychological effects of that stress, and encourage counseling for depression, substance abuse, and other such problems when their first signs appear. Of course, that is a good practice in any event. But its potential side benefit to a legal case is real and worth remembering.

- Remember three definitions.

The factual and legal issues that will ultimately go to trial in cases about Harvey simply cannot be predicted with any specificity. But in the short run, three basic legal concepts are likely to pervade business dealings related to the storm:

- The Texas pattern jury instruction about “duress” defines it as “the mental, physical, or economic coercion of another, causing that party to act contrary to his free will and interest.”

- While “force majeure” is ordinarily defined by a specific contract, it generally refers to an “extraordinary event or circumstance beyond the control of the parties,” and often does not excuse a party’s non-performance entirely, but only suspends it for the duration of the event.

- “Impossibility of performance” is defined by the Restatement (Second) of Contracts as occurring “[w]here, after a contract is made, a party’s performance is made impracticable without his fault by the occurrence of an event the non-occurrence of which was a basic assumption on which the contract was made, his duty to render that performance is discharged, unless the language or the circumstances indicate the contrary.”

Awareness of these concepts can potentially avoid problems down the road, as well as identify topics and issues that require special attention today.

- “Two-deep leadership.”

The Boy Scouts of America strictly follows a policy of “two-deep leadership,” under which two adults should be present at all times when interacting with youth. One benefit of that policy is to avoid “he-said, she-said” disputes between two eyewitnesses with no third–party corroboration. In the stress of dealing with the aftermath of Harvey, involving a business colleague or a friend in important discussions may help the future resolution of a legal matter, if a dispute arises about what was said in those discussions.

- Crowdsource, wisely.

For good or ill, social media has come a long way since Hurricane Katrina. Used judiciously, it can be a good source of information about late-breaking news or the reputation of a particular business. And it can provide a valuable outlet for self-expression after the trauma of Harvey.

But social media posts can survive much longer than the thoughts that prompted them, and rash comments about people or events can come back to haunt the person who makes an ill-advised post. Social media is a valuable conduit for information, and at the same time, it is a reliable creator and collector of potential evidence.

Conclusion

Faced with the reality of recovery from one of the worst storms in the nation’s history, planning for future litigation may seem to be a distant worry. But the foundation for that litigation is being put in place today, intentionally or unintentionally. These five basic ideas may provide ways to place that foundation in a more orderly manner, resulting in a stronger end product.

While arising in the specific context of a defective design claim under state law, Stewart v. Capital Safety USA addressed a broader question about when expert testimony is required to prove a point, as opposed to observations by knowledgeable lay witnesses. The Court held: “To find injury causation here, a jury would at least have to conclude that a different lifeline cable or a different warning would have, under the circumstances of this accident, prevented Stewart’s death. Thus, a jury would be confronted with questions that require a degree of familiarity with such subjects as physics, engineering, and oil rig practices and procedures. This case therefore raises questions that are of ‘sufficient complexity to be beyond the expertise of the average judge and juror’ and that ‘common sense’ does not ‘make[] obvious.'” No. 16-30993-CV (May 30, 2017; published Aug. 21, 2017).

While arising in the specific context of a defective design claim under state law, Stewart v. Capital Safety USA addressed a broader question about when expert testimony is required to prove a point, as opposed to observations by knowledgeable lay witnesses. The Court held: “To find injury causation here, a jury would at least have to conclude that a different lifeline cable or a different warning would have, under the circumstances of this accident, prevented Stewart’s death. Thus, a jury would be confronted with questions that require a degree of familiarity with such subjects as physics, engineering, and oil rig practices and procedures. This case therefore raises questions that are of ‘sufficient complexity to be beyond the expertise of the average judge and juror’ and that ‘common sense’ does not ‘make[] obvious.'” No. 16-30993-CV (May 30, 2017; published Aug. 21, 2017).

An insurance dispute went to final judgment in 2012, was appealed to the Fifth Circuit and ultimately remanded “for further consideration in the light of hte answer given by the Texas Supreme Court in [In re: Deepwater Horizon, 470 S.W.3d 452 (Tex. 2015)]. On remand, after considering the effect of Deepwater Horizon, the district court reinstated its 2012 judgment. In the second appeal, the parties disputed whether “the post-judgment interest rate, which is significantly lower than the applicable pre-judgment interest rate, should apply from the date of the 2012 judgment because that judgment was not materially changed on remand.” The Fifth Circuit agreed that it should run from the 2012 judgment, noting that the district court did not reopen the record, and the judgment did not materially change. ExxonMobil v. Electrical Reliability Servcs., No. 15-20751 (Aug. 22, 2017).

An insurance dispute went to final judgment in 2012, was appealed to the Fifth Circuit and ultimately remanded “for further consideration in the light of hte answer given by the Texas Supreme Court in [In re: Deepwater Horizon, 470 S.W.3d 452 (Tex. 2015)]. On remand, after considering the effect of Deepwater Horizon, the district court reinstated its 2012 judgment. In the second appeal, the parties disputed whether “the post-judgment interest rate, which is significantly lower than the applicable pre-judgment interest rate, should apply from the date of the 2012 judgment because that judgment was not materially changed on remand.” The Fifth Circuit agreed that it should run from the 2012 judgment, noting that the district court did not reopen the record, and the judgment did not materially change. ExxonMobil v. Electrical Reliability Servcs., No. 15-20751 (Aug. 22, 2017).

Sterling Homes, the general contractor on a residential construction project, successfully sued Espinoza, a painting subcontractor, for a fire loss over $1 million. Espinoza’s insurer denied coverage because Sterling Homes was an “additional insured” on Espinoza’s policy, which the insurer said brought the Sterling-Espinoza dispute within the policy’s “cross suits” (or “insured v. insured”) exclusion.. The Fifth Circuit concluded that the plain terms of the exclusion would cover parties that were named as “additional insureds,” in addition to the actualy purchasers of a policy. But as to the specific claims at issue, the Court further held that the exclusion was only intended to apply to Sterling Homes’s liability arising rom Espinoza’s operations, as “nothing in the plain language of the subcontracting agreement obligating Espinoza to name Sterling Homes as an additional insured suggests the parties intended for Espinoza to lose insurance overage in the event Sterling Homes needed to sue him.” Certain Underwriters at Lloyd’s v. Sterling Custom Homes

Sterling Homes, the general contractor on a residential construction project, successfully sued Espinoza, a painting subcontractor, for a fire loss over $1 million. Espinoza’s insurer denied coverage because Sterling Homes was an “additional insured” on Espinoza’s policy, which the insurer said brought the Sterling-Espinoza dispute within the policy’s “cross suits” (or “insured v. insured”) exclusion.. The Fifth Circuit concluded that the plain terms of the exclusion would cover parties that were named as “additional insureds,” in addition to the actualy purchasers of a policy. But as to the specific claims at issue, the Court further held that the exclusion was only intended to apply to Sterling Homes’s liability arising rom Espinoza’s operations, as “nothing in the plain language of the subcontracting agreement obligating Espinoza to name Sterling Homes as an additional insured suggests the parties intended for Espinoza to lose insurance overage in the event Sterling Homes needed to sue him.” Certain Underwriters at Lloyd’s v. Sterling Custom Homes

Body by Cook, Inc. v. State Farm gives a useful reminder about the basic rules for a federal pleading: “[A] complaint may simultaneously satisfy Rule 8’s technical requirements but fail to state a claim under Rule 12(b)(6). Mere compliance with Rule 8 does not itself immunize the complaint against a motion to dismiss. Rule 8(a)(2) specifies the conditions of the formal adequacy of a pleading,” but “it does not specify the conditions of its substantive adequacy, that is, its legal merit.” No. 16-31034-CV (Aug. 24, 2017) (citations omitted).

Body by Cook, Inc. v. State Farm gives a useful reminder about the basic rules for a federal pleading: “[A] complaint may simultaneously satisfy Rule 8’s technical requirements but fail to state a claim under Rule 12(b)(6). Mere compliance with Rule 8 does not itself immunize the complaint against a motion to dismiss. Rule 8(a)(2) specifies the conditions of the formal adequacy of a pleading,” but “it does not specify the conditions of its substantive adequacy, that is, its legal merit.” No. 16-31034-CV (Aug. 24, 2017) (citations omitted).

The process server’s affidavit in Norris v. Causey said that (1) the defendant’s wife “yelled through the door that she would not accept service, and (2) he then posted the summons and complaint on the defendant’s door. The affidavit did not say, however, that these events occurred on the same day, which led to a remand for additional fact-finding by the district court: “It turns out that whether the yelling and posting happened the same day matters a great deal. Leaving a summons and complaint at a residence door, unaccompanied by a refusal to accept service, is not effective service under Rule 4. . . . This means that if Garry’s wife was not present, let alone refusing service, on the day the process server posted the documents on the door, Garry’s service was likely defective. On the other hand, a defendant’s refusal to accept service is not rewarded when the process server announces the nature of the documents and leaves them in close proximity to the defiant defendant.” No. 16-30339 (Aug. 22, 2017).

The process server’s affidavit in Norris v. Causey said that (1) the defendant’s wife “yelled through the door that she would not accept service, and (2) he then posted the summons and complaint on the defendant’s door. The affidavit did not say, however, that these events occurred on the same day, which led to a remand for additional fact-finding by the district court: “It turns out that whether the yelling and posting happened the same day matters a great deal. Leaving a summons and complaint at a residence door, unaccompanied by a refusal to accept service, is not effective service under Rule 4. . . . This means that if Garry’s wife was not present, let alone refusing service, on the day the process server posted the documents on the door, Garry’s service was likely defective. On the other hand, a defendant’s refusal to accept service is not rewarded when the process server announces the nature of the documents and leaves them in close proximity to the defiant defendant.” No. 16-30339 (Aug. 22, 2017).

Yahoo cancelled its contract with SCA related to a billion-dollar “perfect bracket contest” for 2014’s March Madness. The parties disputed the appropriate termination payment, defined in the contract as “50% of the fee” – Yahoo contending the “fee” was 50% of the $1.1 million deposit that it already paid SCA; SCA contending that the “fee” was the rull $11 million contract fee, credited for the deposit. The Fifth Circuit reversed and rendered judgment for SCA, noting that the contract “clear[ly] incorporated by reference two invoices that specified the $11 million figure,” and identifying several other contract provisions consistent with SCA’s reading. The issue of what documents comprise a contract, and the related legal issue of when a court may consider “parol” evidence, continues to be a frequent – if not the most frequent – point of disagreement between the Fifth Circuit and trial courts. SCA Promotions v. Yahoo!, No. 15-11254 (Aug. 21, 2017).

Yahoo cancelled its contract with SCA related to a billion-dollar “perfect bracket contest” for 2014’s March Madness. The parties disputed the appropriate termination payment, defined in the contract as “50% of the fee” – Yahoo contending the “fee” was 50% of the $1.1 million deposit that it already paid SCA; SCA contending that the “fee” was the rull $11 million contract fee, credited for the deposit. The Fifth Circuit reversed and rendered judgment for SCA, noting that the contract “clear[ly] incorporated by reference two invoices that specified the $11 million figure,” and identifying several other contract provisions consistent with SCA’s reading. The issue of what documents comprise a contract, and the related legal issue of when a court may consider “parol” evidence, continues to be a frequent – if not the most frequent – point of disagreement between the Fifth Circuit and trial courts. SCA Promotions v. Yahoo!, No. 15-11254 (Aug. 21, 2017).

After a pipeline breach, a federal regulator penalized ExxonMobil for violating safety rules. The Fifth Circuit reversed, finding, inter alia, that the agency’s interpretation of the “textually unambiguous” regulation required no deference under Auer v. Robbins, 519 U.S. 452 (1997). Specifically, the regulation said that pipeline operators “must consider” “all risk factors that reflect the risk conditions on the pipeline

After a pipeline breach, a federal regulator penalized ExxonMobil for violating safety rules. The Fifth Circuit reversed, finding, inter alia, that the agency’s interpretation of the “textually unambiguous” regulation required no deference under Auer v. Robbins, 519 U.S. 452 (1997). Specifically, the regulation said that pipeline operators “must consider” “all risk factors that reflect the risk conditions on the pipeline  segment.” Concluding (presumably, after due consideration), that “consider” meant “to think about carefully,” the Court concluded that the regulation “unambiguously serves to informs a pipeline operator’s careful and deliberate decision-making process rather than to compel a particular outcome . . . ” This conclusion undermined the substantive basis of the agency’s liability determination, and led to reversal in substantial part. ExxonMobil Pipeline Co. v. U.S. Dep’t of Transp., No. 16-60448 (Aug. 14, 2017).

segment.” Concluding (presumably, after due consideration), that “consider” meant “to think about carefully,” the Court concluded that the regulation “unambiguously serves to informs a pipeline operator’s careful and deliberate decision-making process rather than to compel a particular outcome . . . ” This conclusion undermined the substantive basis of the agency’s liability determination, and led to reversal in substantial part. ExxonMobil Pipeline Co. v. U.S. Dep’t of Transp., No. 16-60448 (Aug. 14, 2017).

The issue in Longhorn Gasket & Supply Co. v. U.S. Fire Ins. Co. was whether asbestos was within the scope of a pollution exclusion that applied to “irritants, contaminants or pollutants.” Acknowledging a dearth of Texas case law on the subject, and lack of a clear trend in opinions nationally, the Fifth Circuit concluded that asbestos was an “irritant” under the commonly-accepted meaning of that term, and the underlying claims thus fell within the scope of the exclusion. The Court then held that because “[w]e have concluded that the pollution exclusion applies . . . the burden shifts to [the insured] to attempt to apply an exception to the exclusion”; in this case whether “such discharge, dispersal, release or escape is sudden and accidental.” No. 15-41625 (Aug. 18, 2017).

The issue in Longhorn Gasket & Supply Co. v. U.S. Fire Ins. Co. was whether asbestos was within the scope of a pollution exclusion that applied to “irritants, contaminants or pollutants.” Acknowledging a dearth of Texas case law on the subject, and lack of a clear trend in opinions nationally, the Fifth Circuit concluded that asbestos was an “irritant” under the commonly-accepted meaning of that term, and the underlying claims thus fell within the scope of the exclusion. The Court then held that because “[w]e have concluded that the pollution exclusion applies . . . the burden shifts to [the insured] to attempt to apply an exception to the exclusion”; in this case whether “such discharge, dispersal, release or escape is sudden and accidental.” No. 15-41625 (Aug. 18, 2017).

I was interviewed today by Fox 4 Dallas about social media and hate speech, in light of recent events in Charlottesville.

by Fox 4 Dallas about social media and hate speech, in light of recent events in Charlottesville.

In a return trip to the Fifth Circuit, the defamation case of Block v. Tanenhaus again sidestepped the question of whether state anti-SLAPP laws apply in federal courrt, allowing that elephant to remain in the Erie room for awhile longer. Here, assuming that the Lousiana state law applied, the panel reversed and remanded the dismissal of a professor’s claim that the New York Times misquoted him. Jess Krochtengel summarizes the underlying Erie question and its implications in a recent Law360 article. No. 16-30966 (Aug. 15, 2017).

In a return trip to the Fifth Circuit, the defamation case of Block v. Tanenhaus again sidestepped the question of whether state anti-SLAPP laws apply in federal courrt, allowing that elephant to remain in the Erie room for awhile longer. Here, assuming that the Lousiana state law applied, the panel reversed and remanded the dismissal of a professor’s claim that the New York Times misquoted him. Jess Krochtengel summarizes the underlying Erie question and its implications in a recent Law360 article. No. 16-30966 (Aug. 15, 2017).

Five LPCH attorneys are on 2018’s list of Best Lawyers in America!

The trial court in Oprex Surgery v. Sonic Automotive Employee Welfare Benefit Plan dismissed Oprex’s complaint for failure to comply with a discovery order; the Fifth Circuit reversed, finding, inter alia:

The trial court in Oprex Surgery v. Sonic Automotive Employee Welfare Benefit Plan dismissed Oprex’s complaint for failure to comply with a discovery order; the Fifth Circuit reversed, finding, inter alia:

- A record of “delay or contumacious conduct” was not established when “Sonic raised no complaint, in a motion to compel or otherwise, regarding the adequacy of Oprex’s responses unitl one hour before the conference” at which dismissal occurred;

- The time and expense of participating in conferences is not “prejudice to ‘the opposing party’s preparation for trial”; and

- “. . . given the important due process concerns implicated by a dismissal with prejudice, the court should at leat consider the efficacy of lesser sanctions first”

No. 16-20734 (Aug. 10, 2017, unpublished).

The common law of contracts was forever shaped by the good ships Peerless (one of which appears to the right), which both sailed into Liverpool in late 1863 bearing loads of cotton from Bombay. A modern counterpoint appears in GIC Services v. Freightplus USA , in which the parties

forever shaped by the good ships Peerless (one of which appears to the right), which both sailed into Liverpool in late 1863 bearing loads of cotton from Bombay. A modern counterpoint appears in GIC Services v. Freightplus USA , in which the parties  were both talking about a tugboat called REBEL (left), but disagreed over what Nigerian city it was supposed to arrive in after a trans-Atlantic journey from Houston. The core problem with the “meeting of the minds,” however,

were both talking about a tugboat called REBEL (left), but disagreed over what Nigerian city it was supposed to arrive in after a trans-Atlantic journey from Houston. The core problem with the “meeting of the minds,” however,  was not among the parties, but among their counsel and the trial court, as the calculation of damages for the prevailing party rested almost entirely on one invoice. The Fifth Circuit panel split 2-1 over whether an effective stipulation had been reached about the authenticity of the invoice, providing a cautionary note to all trial lawyers about the effect and scope of agreements reached “on the fly” in open court. No. 15-30975 (August 8, 2017).

was not among the parties, but among their counsel and the trial court, as the calculation of damages for the prevailing party rested almost entirely on one invoice. The Fifth Circuit panel split 2-1 over whether an effective stipulation had been reached about the authenticity of the invoice, providing a cautionary note to all trial lawyers about the effect and scope of agreements reached “on the fly” in open court. No. 15-30975 (August 8, 2017).

In a topic also addressed on 600Commerce today, the interplay of criminal proceedings and civil litigation can be challenging. The conclusions of In re Grand Jury Subpoena summarized when a stay of civil cases can be required: “It is not necessary that the movant for civil discovery specifically intend to circumvent the rules of criminal discovery: a movant with the ‘purest of motives’ would, in the event the civil case wa allowed to proceed, gain access to materials otherwise unobtainable and, in so doing, potentially harm the related criminal investigation. . . . If not enjoined, further proceedings in state court, including civil discovery, could undermine the federal criminal investigation into [Company]. Furthermore, [Company] will not be unduly burdened if the civil proceedings do not proceed for the duration of the criminal investigation: ownership of the electronic devices can be determined after the investigation is complete, and the devices returned to [Company] if its ownership is established.” No. 16-10181 (Juy 19, 2017).

In a topic also addressed on 600Commerce today, the interplay of criminal proceedings and civil litigation can be challenging. The conclusions of In re Grand Jury Subpoena summarized when a stay of civil cases can be required: “It is not necessary that the movant for civil discovery specifically intend to circumvent the rules of criminal discovery: a movant with the ‘purest of motives’ would, in the event the civil case wa allowed to proceed, gain access to materials otherwise unobtainable and, in so doing, potentially harm the related criminal investigation. . . . If not enjoined, further proceedings in state court, including civil discovery, could undermine the federal criminal investigation into [Company]. Furthermore, [Company] will not be unduly burdened if the civil proceedings do not proceed for the duration of the criminal investigation: ownership of the electronic devices can be determined after the investigation is complete, and the devices returned to [Company] if its ownership is established.” No. 16-10181 (Juy 19, 2017).

Among other holdings in a hard-fought wrongful foreclosure action, the Fifth Circuit made two observations about the FDCPA in Mahmoud v. DeMoss Owners Association. First, while language on the first page of a letter suggested that action was required in less than 30 days, the next page of that letter clearly gave the required 30-day action period in three places, and thus did not violate the FDCPA. Second, even though “a small portion of the debt may have been time-barred,” in the context of a non-judicial foreclosure controlled by state law, that matter alone would not create an FDCPA violation. A dissent had a different view of the point, and “would hold instead that, consistent with the text and spirit of the Act, demanding full repayment of a partiaally time-barred debt under the threat of forecloosure – implying that the entirety of the debt is legally enforceable – violates the FDCPA.” No. 15-20618 (July 28, 2017).

Among other holdings in a hard-fought wrongful foreclosure action, the Fifth Circuit made two observations about the FDCPA in Mahmoud v. DeMoss Owners Association. First, while language on the first page of a letter suggested that action was required in less than 30 days, the next page of that letter clearly gave the required 30-day action period in three places, and thus did not violate the FDCPA. Second, even though “a small portion of the debt may have been time-barred,” in the context of a non-judicial foreclosure controlled by state law, that matter alone would not create an FDCPA violation. A dissent had a different view of the point, and “would hold instead that, consistent with the text and spirit of the Act, demanding full repayment of a partiaally time-barred debt under the threat of forecloosure – implying that the entirety of the debt is legally enforceable – violates the FDCPA.” No. 15-20618 (July 28, 2017).

The Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment for the insured in a dispute about “advertising injury” coverage, finding that the underlying pleading “alleged misrepresentations . . . directed at a particular potential customer in reference to a particular project that a competitor was undertaking. It thus impugned a particular competitor and its services by necessary implication” (thus distinguishing KLN Steel Prods. Co. v. CNA Ins. Cos., 278 S.W.3d 429 (Tex. App.–San Antonio 2008, pet. denied)). This brought the claim within the policy, which covered “injury . . . arising out of the oral or written publication, in any manner, or material that disparages a person’s or organization’s goods, products or services.” Uretek (USA), Inc. v. Continental Casualty Co., No. 15-20104 (July 28, 2017).

The Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment for the insured in a dispute about “advertising injury” coverage, finding that the underlying pleading “alleged misrepresentations . . . directed at a particular potential customer in reference to a particular project that a competitor was undertaking. It thus impugned a particular competitor and its services by necessary implication” (thus distinguishing KLN Steel Prods. Co. v. CNA Ins. Cos., 278 S.W.3d 429 (Tex. App.–San Antonio 2008, pet. denied)). This brought the claim within the policy, which covered “injury . . . arising out of the oral or written publication, in any manner, or material that disparages a person’s or organization’s goods, products or services.” Uretek (USA), Inc. v. Continental Casualty Co., No. 15-20104 (July 28, 2017).

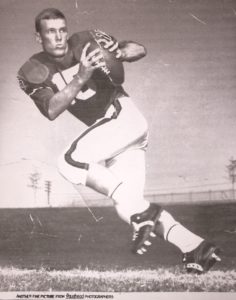

In a thorough review of several basic issues that arise in litigation about residential foreclosures, the Fifth Circuit addressed whether the citizenship of a mortgage securitization trust is determined by the citizenship of the trustee, or the citizenship of all the trust’s interest holders. While the traditional rule is that the citizenship of the trustee controls, Navarro Savings Ass’n v. Lee, 446 U.S. 458 (1980), the borrower argued that a more recent case about the citizenship of a REIT should control, Americold Relay Trust v. Conagra Foods, 136 S. Ct. 1012 (2016). Because the defendant bank was sued in its capacity as trusteee, and because the terms of the Pooling and Service Agreement assigned “real and substantial” control to the bank, the Court elected to follow Navarro. Bynane v. The Bank of New York Mellon, No. 16-20598 (August 4, 2017) (Navarro was sucessfully argued in the Supreme Court by my former law partner James Ellis, an excellent lawyer and as shown above, a star quarterback at Texas Tech in the early 1960s).

In a thorough review of several basic issues that arise in litigation about residential foreclosures, the Fifth Circuit addressed whether the citizenship of a mortgage securitization trust is determined by the citizenship of the trustee, or the citizenship of all the trust’s interest holders. While the traditional rule is that the citizenship of the trustee controls, Navarro Savings Ass’n v. Lee, 446 U.S. 458 (1980), the borrower argued that a more recent case about the citizenship of a REIT should control, Americold Relay Trust v. Conagra Foods, 136 S. Ct. 1012 (2016). Because the defendant bank was sued in its capacity as trusteee, and because the terms of the Pooling and Service Agreement assigned “real and substantial” control to the bank, the Court elected to follow Navarro. Bynane v. The Bank of New York Mellon, No. 16-20598 (August 4, 2017) (Navarro was sucessfully argued in the Supreme Court by my former law partner James Ellis, an excellent lawyer and as shown above, a star quarterback at Texas Tech in the early 1960s).

In Hills v. Entergy Operations, Inc., a case about overtime pay for security guards, the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment based upon a conclusion about two guards’ lack of damage. While the Court’s holding was based upon technical issues of employment law, its underlying reasoning is of broader applicability: “We reverse the district court’s summary judgment that the fluctuating workweek method applies here as a matter of law. The underlying factual issue upon which the applicabilty of that method is predicated, what the employees clearly understood, should be decided at trial in due course.” No. 16-30924 (Aug. 4, 2017). Also, in a ruling of general interest about administrative law, the Court declined to follow an interpretive letter by the Department of Labor.

In Hills v. Entergy Operations, Inc., a case about overtime pay for security guards, the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment based upon a conclusion about two guards’ lack of damage. While the Court’s holding was based upon technical issues of employment law, its underlying reasoning is of broader applicability: “We reverse the district court’s summary judgment that the fluctuating workweek method applies here as a matter of law. The underlying factual issue upon which the applicabilty of that method is predicated, what the employees clearly understood, should be decided at trial in due course.” No. 16-30924 (Aug. 4, 2017). Also, in a ruling of general interest about administrative law, the Court declined to follow an interpretive letter by the Department of Labor.

The City of Cibolo, Texas, sought to establish sewer service that would conflict with the Greeny Valley Special Utility District’s right to provide such service under a federal program. The dispute turned on the meaning of the phrase “the service” in the relevant statute – the resulting analysis (a) resolved that use of “the” is not dispositive, since its meaning depends on the following noun, and (b) Congress’s many different uses of “service” and “services” in the pertinent set of statutes was not controlling. The Fifth Circuit concluded that the plain terms of the statute required it to “decline the city’s invitation to read adjectives” into the phrase “the service,” and it reversed the district court’s ruling that had limited the phrase to services financed by a federal loan. Green Valley Special Utility District v. City of Cibolo, No.16-51282 (Aug. 2, 2017).

The City of Cibolo, Texas, sought to establish sewer service that would conflict with the Greeny Valley Special Utility District’s right to provide such service under a federal program. The dispute turned on the meaning of the phrase “the service” in the relevant statute – the resulting analysis (a) resolved that use of “the” is not dispositive, since its meaning depends on the following noun, and (b) Congress’s many different uses of “service” and “services” in the pertinent set of statutes was not controlling. The Fifth Circuit concluded that the plain terms of the statute required it to “decline the city’s invitation to read adjectives” into the phrase “the service,” and it reversed the district court’s ruling that had limited the phrase to services financed by a federal loan. Green Valley Special Utility District v. City of Cibolo, No.16-51282 (Aug. 2, 2017).

Dominguez had “a series of mishaps during discovery” in his Jones Act case. The district court ultimately dismissed his claims, but the Fifth Circuit reversed in favor of a less severe sanction. The key discovery problem was Dominguez’s failure to attend an independent medical exam, but that exam was called for because of an opinion from a medical expert offered by Dominguezz. “[E]xcluding [the expert] from the proceedings would have eliminatedd the immediate cause of delay and any prejudice to [Defendant] without dismissing Dominguez’s underlying personal injury claims in their entirety.” Dominguez v. Crosby Tugs, LLC, No. 16-31239 (Aug. 1, 2017).

Dominguez had “a series of mishaps during discovery” in his Jones Act case. The district court ultimately dismissed his claims, but the Fifth Circuit reversed in favor of a less severe sanction. The key discovery problem was Dominguez’s failure to attend an independent medical exam, but that exam was called for because of an opinion from a medical expert offered by Dominguezz. “[E]xcluding [the expert] from the proceedings would have eliminatedd the immediate cause of delay and any prejudice to [Defendant] without dismissing Dominguez’s underlying personal injury claims in their entirety.” Dominguez v. Crosby Tugs, LLC, No. 16-31239 (Aug. 1, 2017).

Laney Chiropractic v. Nationwide Mutual Ins. Co. presented a dispute about whether “advertising injury,” covered by insurance, was raised by a complaint about a competitor’s statements about a chiropractic massage technique. The Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for the insurer, finding, inter alia: “[W]hen an insured is accused of using another’s product, they are generally not using another’s ‘advertising idea.’ . . . And that is precisely what the Underlying Complaint alleges. It alleges that Laney unlawfully used a patented product . . . and then advertised the product on its website.” Arguments based on alleged trade dress and slogan infringement failed for similar reasons. No. 16-1183 (July 28, 2017)

Laney Chiropractic v. Nationwide Mutual Ins. Co. presented a dispute about whether “advertising injury,” covered by insurance, was raised by a complaint about a competitor’s statements about a chiropractic massage technique. The Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for the insurer, finding, inter alia: “[W]hen an insured is accused of using another’s product, they are generally not using another’s ‘advertising idea.’ . . . And that is precisely what the Underlying Complaint alleges. It alleges that Laney unlawfully used a patented product . . . and then advertised the product on its website.” Arguments based on alleged trade dress and slogan infringement failed for similar reasons. No. 16-1183 (July 28, 2017)

Celebrate Christmas in July and read about five business cases from the Fifth Circuit in 2017 that you should know.

Celebrate Christmas in July and read about five business cases from the Fifth Circuit in 2017 that you should know.

McCarty fell outside a restaurant kitchen; her subsequent lawsuit against the restaurant for premises liability failed for lack of evidence. The Fifth Circuit distinguished the Texas appellate authority she cited by observing: “The evidence in each of these cases provided context for how long the hazardous condition had existed, in the form of either a discrete and readily documented antecedent event (e.g., a rainfall) or an attribute of the hazard (e.g., a puddle’s size, from which the jury could reasonably infer how long the puddle had been growing). In this case, by contrast, no evidence would permit the jury to trace the alleged slip risk to a particular antecedent event. Nor could a jury infer from any attributes of the alleged hazard that it had been growing over any length of time.” McCarty v. Hillstone Restaurant Group, No. 16-11519 (July 18, 2017).

McCarty fell outside a restaurant kitchen; her subsequent lawsuit against the restaurant for premises liability failed for lack of evidence. The Fifth Circuit distinguished the Texas appellate authority she cited by observing: “The evidence in each of these cases provided context for how long the hazardous condition had existed, in the form of either a discrete and readily documented antecedent event (e.g., a rainfall) or an attribute of the hazard (e.g., a puddle’s size, from which the jury could reasonably infer how long the puddle had been growing). In this case, by contrast, no evidence would permit the jury to trace the alleged slip risk to a particular antecedent event. Nor could a jury infer from any attributes of the alleged hazard that it had been growing over any length of time.” McCarty v. Hillstone Restaurant Group, No. 16-11519 (July 18, 2017).

The bankruptcy court ruled that a claim against the debtor, arising out of a scheme involving foreclosure proceedings, was nondischargeable. The Fifth Circuit affirmed, holding, inter alia, that the debt could be found nondischargeable because of the debtor’s participation in a civil conspiracy involving the scheme: “[Bankruptcy Code ] ection 523(a)(4) excepts from discharge debts ‘for . . . larceny.’ The text adds no further criteria or qualifications. Like § 523(a)(2), a plain reading of the provision is that a debtor cannot discharge a debt that arises from larceny so long as the debtor is liable to the creditor for the larceny. It is the character of the debt rather than the character of the debtor that determines whether the debt is nondischargeable under § 523(a)(4).” Cowin v. Countrywide Home Loans, No. 15-20600 (July 18, 2017).

The bankruptcy court ruled that a claim against the debtor, arising out of a scheme involving foreclosure proceedings, was nondischargeable. The Fifth Circuit affirmed, holding, inter alia, that the debt could be found nondischargeable because of the debtor’s participation in a civil conspiracy involving the scheme: “[Bankruptcy Code ] ection 523(a)(4) excepts from discharge debts ‘for . . . larceny.’ The text adds no further criteria or qualifications. Like § 523(a)(2), a plain reading of the provision is that a debtor cannot discharge a debt that arises from larceny so long as the debtor is liable to the creditor for the larceny. It is the character of the debt rather than the character of the debtor that determines whether the debt is nondischargeable under § 523(a)(4).” Cowin v. Countrywide Home Loans, No. 15-20600 (July 18, 2017).

Duggan, an non-named member of a class certified under Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b)(1), made an untimely objection to the fairness of the class settlement. While he was not a named party, he sought to appeal under the doctrine recognized by Devlin v. Scardelletti, 536 U.S. 1 (2002), which allowed non-named class members “who have objected in a timely manner to approval of the settlement at the fairness hearing have the power to bring an appeal without first intervening.” Unfortunately for Duggan, the Fifth Circuit found no reason to excuse his late objection, in particular rejecting the argument that his opponent was required to move to strike the objection in district court as a prerequisite to arguing waiver on appeal. Farber v. Crestwood Midstream Partners LP , No. 16-20742 (July 17, 2017).

Duggan, an non-named member of a class certified under Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b)(1), made an untimely objection to the fairness of the class settlement. While he was not a named party, he sought to appeal under the doctrine recognized by Devlin v. Scardelletti, 536 U.S. 1 (2002), which allowed non-named class members “who have objected in a timely manner to approval of the settlement at the fairness hearing have the power to bring an appeal without first intervening.” Unfortunately for Duggan, the Fifth Circuit found no reason to excuse his late objection, in particular rejecting the argument that his opponent was required to move to strike the objection in district court as a prerequisite to arguing waiver on appeal. Farber v. Crestwood Midstream Partners LP , No. 16-20742 (July 17, 2017).

Duncan, a Wal-Mart employee, slipped on a mat near an ice freezer in the store. She sued for her injuries and the Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for the defense, noting several ways in which her proof of a dangerous condition was lacking: “In Duncan’s deposition—the only evidence she and Johnson submitted in support of their claim—she repeatedly explained that she did not know how water developed under the mat on which she slipped. Duncan couldn’t say whether water had ‘somehow leaked or spilled underneath the mat’ or whether ‘something on top of the mat . . . leaked through it.’ No one at Wal-Mart told her that they knew there was water in that area before she fell, and she didn’t know whether water had ever accumulated in that area before. Duncan also said that in the four years she worked at Wal-Mart, she had never heard of the Reddy Ice machine leaking, even though she knew other appliances, like the ‘Coke machine,’ leaked. ” Duncan v. Wal-Mart Louisiana LLC, No. 16-31223 (July 14, 2017).

I recently participated in a mock reargument of Marbury v. Madison (right), albeit changed from the original to (1) actually have discussion about judicial review (2) actually have participation by my character, Attorney General Levi Lincoln, who in “real life” was ordered to stay silent by a highly irritated President Jefferson. In case you should ever need such a thing, here are my notes about the case against judicial review, which rely heavily upon an outstanding 1969 Duke Law Journal article by Professor William Van Alstyne.

I recently participated in a mock reargument of Marbury v. Madison (right), albeit changed from the original to (1) actually have discussion about judicial review (2) actually have participation by my character, Attorney General Levi Lincoln, who in “real life” was ordered to stay silent by a highly irritated President Jefferson. In case you should ever need such a thing, here are my notes about the case against judicial review, which rely heavily upon an outstanding 1969 Duke Law Journal article by Professor William Van Alstyne.

Litigation continues on the Texas tollroads, most recently producing a defamation lawsuit in BancPass v. Highway Toll Administration LLC, arising from letters sent by a company’s competitors to Google and Apple. The defendant unsuccessfully argued that the letters were immune from liability by the Texas privilege associated with court proceedings.

Litigation continues on the Texas tollroads, most recently producing a defamation lawsuit in BancPass v. Highway Toll Administration LLC, arising from letters sent by a company’s competitors to Google and Apple. The defendant unsuccessfully argued that the letters were immune from liability by the Texas privilege associated with court proceedings.

Before the Fifth Circuit, matters began well for the defendant – the Court concluded (1) that an immediate interlocutory appeal was allowed because the Texas privilege protects from suit, not just liability, and (2) while “[c]ertainly, the district court expressed its displeasure” at this issue arising late in the proceedings, it did not formally certify the appeal as frivolous (and thus avoided a line of cases that would otherwise have undermined defendant’s appeal right). But on the merits:

“Texas caselaw is clear that our analysis must focus on the connection between the communications and the specific legal action HTA now claims that it was contemplating, rather than legal action more broadly. The letters to Google and Apple in particular put forward bare accusations of unlawful conduct that was unrelated to HTA’s later tortious interference claim and that neither directly implicated HTA’s own legal rights nor constituted legal claims that HTA had any ability to pursue.”

“Texas caselaw is clear that our analysis must focus on the connection between the communications and the specific legal action HTA now claims that it was contemplating, rather than legal action more broadly. The letters to Google and Apple in particular put forward bare accusations of unlawful conduct that was unrelated to HTA’s later tortious interference claim and that neither directly implicated HTA’s own legal rights nor constituted legal claims that HTA had any ability to pursue.”

No. 16-51073 (July 13, 2017).

The Fifth Circuit recently granted rehearing en banc in two civil cases – Ariana M. v. Humana Health Services, 853 F.3d 753 (5th Cir. 2017), which reviewed the decisions of an ERISA plan administrator, and In re: Doiron, 849 F.3d 602 (5th Cir. 2017), which addressed whether a contract was “maritime” in nature. The common thread? Both opinions made express appeals to the full court for review:

The Fifth Circuit recently granted rehearing en banc in two civil cases – Ariana M. v. Humana Health Services, 853 F.3d 753 (5th Cir. 2017), which reviewed the decisions of an ERISA plan administrator, and In re: Doiron, 849 F.3d 602 (5th Cir. 2017), which addressed whether a contract was “maritime” in nature. The common thread? Both opinions made express appeals to the full court for review:

- In Ariana, all three panel members who joined in the same opinion also joined in a special concurrence: “As any sports fan dismayed that instant replay did not overturn a blown call learns, it is difficult to overcome a deferential standard of review. The deferential standard of review our court applies to ERISA decisions often determines the outcome of disputes that are far more important than a sporting event: decisions made by retirement and health plans during some of life’s most difficult times, as this case involving a teenager with a serious eating disorder demonstrates. So it is striking that we are the only circuit that would apply that deference to factual determinations made by an ERISA administrator when the plan does not vest them with that discretion.” (emphasis added)

- And the conclusion of the unanimous Dorian panel opinion said: “It is time to abandon the Davis & Sons test for determining whether or not a contract is a maritime contract. The test relies more on tort principles than contract principles to decide a contract case. It is too flexible to allow parties or their attorneys to predict whether a court will decide if a contract is maritime or non-maritime or for judges to decide the cases consistently. The Supreme Court’s decision in Kirby reinforces this conclusion. Just as important, the above test will allow all parties to the contract to more accurately allocate risks and determine their insurance needs more reliably.” (emphasis added)

While not within the usual subject matter of this blog, the general importance to Texas business litigation of the Eastern District’s June 30 decision in Raytheon Co. v. Cray, Inc. warrants attention. Raytheon sued Cray in the Marshall Division of the Eastern District for alleged infringement of at least two patents about supercomputer systems. After the Supreme Court’s recent opinion in TC Heartland LLC v. Kraft Foods Grp. Brands LLC, 137 S. Ct. 1514 (2017), Cray moved to transfer, arguing that it (1) did not reside in the district and (2) had not committed acts of infringement or had a regular and established place of business there. The Eastern District adopted a four-factor test and denied the motion, examining —

While not within the usual subject matter of this blog, the general importance to Texas business litigation of the Eastern District’s June 30 decision in Raytheon Co. v. Cray, Inc. warrants attention. Raytheon sued Cray in the Marshall Division of the Eastern District for alleged infringement of at least two patents about supercomputer systems. After the Supreme Court’s recent opinion in TC Heartland LLC v. Kraft Foods Grp. Brands LLC, 137 S. Ct. 1514 (2017), Cray moved to transfer, arguing that it (1) did not reside in the district and (2) had not committed acts of infringement or had a regular and established place of business there. The Eastern District adopted a four-factor test and denied the motion, examining —

- physical presence “including but not limited to property, inventory, infrastructure, or people”;

- defendant’s representations “internatlly or externally, that is has a presence in the district”;

- benefits received from the defendant’s presence in the district, “including but not limited to sales revenue”; and

- “the extent to which a defendant interacts in a targeted way with existing or potential customers, consumers, users or entities within a district, including but not limited to through localized customer support, ongoing contractual relationships, or targeted marketing efforts.”

No. 2:15-CV-01554-JRG (June 29, 2017).

By summary judgment, Advanced Recovery Systems lost a case brought under section 8 of the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, alleging that it failed to disclose on credit reports that the plaintiff disputed two allegedly unpaid debts. Procedurally, while the summary judgment did not follow the traditional Rule 56 schedule, the Fifth Circuit found no harm because ARS had admitted to the district court that there were no remaining issues of fact. Substantively, the Court rejected a challenge to Article III standing, finding that the plaintiff’s injury was sufficiently “tangible” — “[T]he violation of a procedural right granted by statute can be sufficient in some circumstances to constitute injury in fact .. . . Among those circumstances are cases where a statutory violation creates the ‘risk of real harm’ . . . Unlike an incorrect zip code, the ‘bare procedural violation’ in [Spokeo, Inc. v. Robins, 136 S. Ct. 1540, 1549 (2016)], an inaccurate credit rating creates a substantial risk of harm.” Sayles v. Advanced Recovery Systems, Inc., No. 16-60640 (July 6, 2017).

By summary judgment, Advanced Recovery Systems lost a case brought under section 8 of the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, alleging that it failed to disclose on credit reports that the plaintiff disputed two allegedly unpaid debts. Procedurally, while the summary judgment did not follow the traditional Rule 56 schedule, the Fifth Circuit found no harm because ARS had admitted to the district court that there were no remaining issues of fact. Substantively, the Court rejected a challenge to Article III standing, finding that the plaintiff’s injury was sufficiently “tangible” — “[T]he violation of a procedural right granted by statute can be sufficient in some circumstances to constitute injury in fact .. . . Among those circumstances are cases where a statutory violation creates the ‘risk of real harm’ . . . Unlike an incorrect zip code, the ‘bare procedural violation’ in [Spokeo, Inc. v. Robins, 136 S. Ct. 1540, 1549 (2016)], an inaccurate credit rating creates a substantial risk of harm.” Sayles v. Advanced Recovery Systems, Inc., No. 16-60640 (July 6, 2017).

A recurring issue in contract litigation is whether a provision creates a “condition precedent” to the performance of other obligations. In Red Hook Communications I, LP v. On-Site Manager, Inc., the Fifth Circuit identified this provision as one that “plainly creates a condition precedent that both [parties] must comply with before either can bring suit (and thus, denying subject matter jurisdiction if it is not complied with): “[T]he Indemnifying Party and the Indemnified Party will, for a period of sixty (60) days following delivery of such objection, use good faith efforts to resolve the Dispute.” No. 16-11351 (July 3, 2017, unpublished).

A recurring issue in contract litigation is whether a provision creates a “condition precedent” to the performance of other obligations. In Red Hook Communications I, LP v. On-Site Manager, Inc., the Fifth Circuit identified this provision as one that “plainly creates a condition precedent that both [parties] must comply with before either can bring suit (and thus, denying subject matter jurisdiction if it is not complied with): “[T]he Indemnifying Party and the Indemnified Party will, for a period of sixty (60) days following delivery of such objection, use good faith efforts to resolve the Dispute.” No. 16-11351 (July 3, 2017, unpublished).

In St. Joseph Abbey v. Castille, 712 F.3d 215 (5th Cir. 2013), the Fifth Circuit struck down a state-law restriction on the sale of funeral caskets by a monastery, finding that the state had no rational basis for that restriction. Cautious about encouraging similar challenges to economic regulation, the Court warned: “Nor is the ghost of Lochner lurking about. . . . We insist only that Louisiana’s regulation not be irrational—the outer-most limits of due process and equal protection . . . . ”

In St. Joseph Abbey v. Castille, 712 F.3d 215 (5th Cir. 2013), the Fifth Circuit struck down a state-law restriction on the sale of funeral caskets by a monastery, finding that the state had no rational basis for that restriction. Cautious about encouraging similar challenges to economic regulation, the Court warned: “Nor is the ghost of Lochner lurking about. . . . We insist only that Louisiana’s regulation not be irrational—the outer-most limits of due process and equal protection . . . . ”

The recent case o f Reyes v. North Texas Tollway Authority confiirms that if the ghost of Lochner chooses to lurk on Dallas-area tollways, it will have to pay its toll charges timely. It found that the NTTA’s system for charging late fees has a rational basis in both its legitimate need to recover collection costs and desire to encourage the use of TollTags, and concluded: “The Zip Cash system with its challenged fees is the type of novel policymaking for which the limited scrutiny of rational basis review is most justified. . . . The political process may continue to fine tune toll collection, but that is not the Due Process Clause’s role to play.”

f Reyes v. North Texas Tollway Authority confiirms that if the ghost of Lochner chooses to lurk on Dallas-area tollways, it will have to pay its toll charges timely. It found that the NTTA’s system for charging late fees has a rational basis in both its legitimate need to recover collection costs and desire to encourage the use of TollTags, and concluded: “The Zip Cash system with its challenged fees is the type of novel policymaking for which the limited scrutiny of rational basis review is most justified. . . . The political process may continue to fine tune toll collection, but that is not the Due Process Clause’s role to play.”

In so doing, the Court clarified a sometimes-confusing principle about the legal standard: “[G]overnment action that applies broadly gets rational basis [review]; government action that is individualized to one of a few plaintiffs gets [‘]shocks the conscience[‘] review.” No. 16-10767 (June 27, 2017).

Servisair bought a workers’ compensation policy from Liberty Mutual, “There is no dispute that Servisair significantly over-allocated payroll to clerical employees, which is a considerably less expensive classification.” Thus, after the payroll period ended and an audit concluded, Liberty Mutual billed Servisair for $3.6 million in additional premium. Servisair alleged a mistake in the “underlying factual basis” relied upon “in negotiating and agreeing to the policy,” but the Fifth Circuit sided with Liberty Mutual, noting that the policy expressly stated: “If the final premium is more than the premium [Servisair] paid to [Liberty Mutual], [Servisair] must pay [Liberty Mutual the balance.” In other words, “[t]his is an open-ended obligation with no limit on the amount of additional premium Servisair might ultimately owe.” In sum: “Servisair made a deal that, in retrospect, it did not like. That does not allow it to rewrite or avoid its obligations.” Liberty Mutual Ins. Co. v. Servisair, LLC, No. 16-20472 (June 27, 2017, unpublished).

Servisair bought a workers’ compensation policy from Liberty Mutual, “There is no dispute that Servisair significantly over-allocated payroll to clerical employees, which is a considerably less expensive classification.” Thus, after the payroll period ended and an audit concluded, Liberty Mutual billed Servisair for $3.6 million in additional premium. Servisair alleged a mistake in the “underlying factual basis” relied upon “in negotiating and agreeing to the policy,” but the Fifth Circuit sided with Liberty Mutual, noting that the policy expressly stated: “If the final premium is more than the premium [Servisair] paid to [Liberty Mutual], [Servisair] must pay [Liberty Mutual the balance.” In other words, “[t]his is an open-ended obligation with no limit on the amount of additional premium Servisair might ultimately owe.” In sum: “Servisair made a deal that, in retrospect, it did not like. That does not allow it to rewrite or avoid its obligations.” Liberty Mutual Ins. Co. v. Servisair, LLC, No. 16-20472 (June 27, 2017, unpublished).

Welsh unsuccessfully sued her employer for allegedly retaliating against her for filing an EEOC charge in 2012. Welsh then sued her employer again in 2015, alleging discrimination based on incidents occurring between April and December of 2014. The district court granted summmary judgment for the defense on res judicata grounds, and the Fifth Circuit reversed. Reviewing Texas law about claim preclusion, pleading amendments, and compulsory counterclaims, the Court concluded: “[W]e reject [Defendant’s] argument that Welsh was required to amend her petition in Welsh I to include claims that were not mature at the time of filing Welsh I. We specifically reject the idea that every time something happens after a lawsuir is filed the plaintiff must immediately amend or risk losing that claim forever.” Welsh v. Fort Bend ISD, No. 16-20538 (June 22, 2017).

Welsh unsuccessfully sued her employer for allegedly retaliating against her for filing an EEOC charge in 2012. Welsh then sued her employer again in 2015, alleging discrimination based on incidents occurring between April and December of 2014. The district court granted summmary judgment for the defense on res judicata grounds, and the Fifth Circuit reversed. Reviewing Texas law about claim preclusion, pleading amendments, and compulsory counterclaims, the Court concluded: “[W]e reject [Defendant’s] argument that Welsh was required to amend her petition in Welsh I to include claims that were not mature at the time of filing Welsh I. We specifically reject the idea that every time something happens after a lawsuir is filed the plaintiff must immediately amend or risk losing that claim forever.” Welsh v. Fort Bend ISD, No. 16-20538 (June 22, 2017).

In the course of affirming a substantial judgment for misappropriation of trade secrets, the Fifth Circuit made an interesting observation in a footnote about liability for civil conspiracy under Texas law: “For instance, [Defendant] argues he is entitled to judgment on the conspiracy to misappropriate claim because such a claim is barred by Texas’ intra-corporate conspiracy doctrine, i.e., that a corporation and its employees cannot conspire with each other in carrying out a company’s business. He has presented no case applying it to the instant situation, where the conspiracy predated even the creation of the company at issue. Here, [Defendant] stole [Plaintiff’s] trade secrets months before the creation of SXP, and the creation and operation of SXP was the means by which the conspiracy was carried out.” Quantlab Technologies v. Kuharsky, No. 16-20242 (June 22, 2017, unpublished).

In the course of affirming a substantial judgment for misappropriation of trade secrets, the Fifth Circuit made an interesting observation in a footnote about liability for civil conspiracy under Texas law: “For instance, [Defendant] argues he is entitled to judgment on the conspiracy to misappropriate claim because such a claim is barred by Texas’ intra-corporate conspiracy doctrine, i.e., that a corporation and its employees cannot conspire with each other in carrying out a company’s business. He has presented no case applying it to the instant situation, where the conspiracy predated even the creation of the company at issue. Here, [Defendant] stole [Plaintiff’s] trade secrets months before the creation of SXP, and the creation and operation of SXP was the means by which the conspiracy was carried out.” Quantlab Technologies v. Kuharsky, No. 16-20242 (June 22, 2017, unpublished).

While otherwise affirming a judgment in the plaintiff’s favor, in Merrit Hawkins & Associates v. Gresham the Fifth Circuit vacated an award of exemplary damages under Texas law in a non-compete case. It distinguished the plaintiff’s authorities by saying: “Unlike in those cases, the only argument and evidence that [plainitff] MHA presented to the jury on the issue of exemplary damages was that [defendant] Consilium intentionally breached the non-compete contract. MHA claimed that ‘the circumstances of this case [were] quite egregious, that everything was intentional, [Consilium] knew [MHA] had these agreements . . . and they breached them anyway.’ However, this is the exact type of argument that the Texas Supreme Court explains is insufficient to show malice when an element of the underlying cause of action is willful harm. Even drawing all inferences in favor of MHA, the additional evidence MHA points to is insufficient to show that Consilium acted with specific intent to cause substantial harm to MHA. The proximity of the two businesses, without more, does not lead to the conclusion that Consilium acted with malice towards MHA. And the fact that Consilium’s founder was a partner at MHA was not raised for the purpose of showing that MHA engaged in a strategic plan of hiring away MHA employees to harm it, but rather to show that Consilium was aware that MHA’s employees had non-compete agreements. Moreover, MHA has never claimed that Consilium induced [the employee] to steal or use its proprietary information . . . .” No. 16-10439 (June 21, 2017).

While otherwise affirming a judgment in the plaintiff’s favor, in Merrit Hawkins & Associates v. Gresham the Fifth Circuit vacated an award of exemplary damages under Texas law in a non-compete case. It distinguished the plaintiff’s authorities by saying: “Unlike in those cases, the only argument and evidence that [plainitff] MHA presented to the jury on the issue of exemplary damages was that [defendant] Consilium intentionally breached the non-compete contract. MHA claimed that ‘the circumstances of this case [were] quite egregious, that everything was intentional, [Consilium] knew [MHA] had these agreements . . . and they breached them anyway.’ However, this is the exact type of argument that the Texas Supreme Court explains is insufficient to show malice when an element of the underlying cause of action is willful harm. Even drawing all inferences in favor of MHA, the additional evidence MHA points to is insufficient to show that Consilium acted with specific intent to cause substantial harm to MHA. The proximity of the two businesses, without more, does not lead to the conclusion that Consilium acted with malice towards MHA. And the fact that Consilium’s founder was a partner at MHA was not raised for the purpose of showing that MHA engaged in a strategic plan of hiring away MHA employees to harm it, but rather to show that Consilium was aware that MHA’s employees had non-compete agreements. Moreover, MHA has never claimed that Consilium induced [the employee] to steal or use its proprietary information . . . .” No. 16-10439 (June 21, 2017).

The Fifth Circuit website has recently posted an “Important Note Regarding FRAP 28(j) Filings,” which reminds: “Counsel sometimes file a FRAP 28(j) letter after oral argument, ostensibly to provide information requested by the court, but make supplemental argument in the filing. . . . [U]nless authorized or requested by the panel, it is improper to make supplemental argument in the letter.”

The Fifth Circuit website has recently posted an “Important Note Regarding FRAP 28(j) Filings,” which reminds: “Counsel sometimes file a FRAP 28(j) letter after oral argument, ostensibly to provide information requested by the court, but make supplemental argument in the filing. . . . [U]nless authorized or requested by the panel, it is improper to make supplemental argument in the letter.”

Longtime Texas practitioners will remember when lawyer ads had to contain a cumbersome notice that the attorney was “NOT BOARD CERTIFIED – TEXAS BOARD OF LEGAL SPECIALIZATION” if he or she did not have a TBLS certification. The dental field bit into a similar regulation in American Academy of Implant Dentistry v. Parke, which prohibited claims of specialization in areas not

Longtime Texas practitioners will remember when lawyer ads had to contain a cumbersome notice that the attorney was “NOT BOARD CERTIFIED – TEXAS BOARD OF LEGAL SPECIALIZATION” if he or she did not have a TBLS certification. The dental field bit into a similar regulation in American Academy of Implant Dentistry v. Parke, which prohibited claims of specialization in areas not  recognized by the American Dental Association. The Fifth Circuit panel majority, after chewing on the First Amendment framework for the regulation of commercial speech, found a poor bridge between the asserted government interest and the scope of the regulation, making it unconstitutional. A dissent would have affirmed the regulation as addressing “inherently misleading” speech, which is rooted in a different First Amendment framework. No. 16-50157 (June 19, 2017).

recognized by the American Dental Association. The Fifth Circuit panel majority, after chewing on the First Amendment framework for the regulation of commercial speech, found a poor bridge between the asserted government interest and the scope of the regulation, making it unconstitutional. A dissent would have affirmed the regulation as addressing “inherently misleading” speech, which is rooted in a different First Amendment framework. No. 16-50157 (June 19, 2017).

In ASARCO LLC v. Montana Resources, Inc., a case involving the interplay of a business’s bankruptcy with a later lawsuit for breach of contract by that business, the Fifth Circuit observed:

In ASARCO LLC v. Montana Resources, Inc., a case involving the interplay of a business’s bankruptcy with a later lawsuit for breach of contract by that business, the Fifth Circuit observed:

- “[A] declaratory claim on its own typically will not preclude future claims involving the same circumstances (as noted, issue preclusion may still apply to any declaration the court issues). But in a case involving both declaratory claims and ones seeking coercive relief, the former will not serve as an antidote that undoes the preclusive force that traditional claims would ordinarily have.” (applying the “seminal case” on the point, Kaspar Wire Works, Inc. v. Leco Engineering & Machine, Inc., 575 F.2d 530 (5th Cir. 1978))

- As to the damages claim, “ASARCO’s claim for failure to reinstate did not accrue until MRI rejected the tender in 2011. . . . ASARCO may or may not have attempted to cure, and MRI may or may not have denied ASARCO’s reinstatement. Because the present breach of contract claim was contingent on future events, ASARCO could not have brought it during the adversary proceeding.”

- For the same reasons, the plaintiff was not judicially estopped by allegedly inadequate disclosures during the earlier bankruptcy: “MRI cites no case requiring a party to disclose a potential claim for breach of contract when the contract had not yet been breached. This makes sense, because MRI’s position would require a debtor to scour its contracts looking for hypothetical claims that another party could maybe breach in the future.”

No. 16-40682 (June 2, 2017).

While this story does not involve federal practice, the recent death of former Dallas Court of Appeals Justice David Lewis, who resigned from that Court last year to combat alcoholism and depression, sounds a warning note for all in the legal profession about the importance of mental health.

For those who enjoy topics even more arcane than the basic Rooker-Feldman doctrine, there is Kreit v. Quinn, No. 16-20744 (June 13, 2017, unpublished). A state court appointed a receiver for a hospital, which then entered bankruptcy. The bankruptcy court approved a sale, a doctor strenuously

For those who enjoy topics even more arcane than the basic Rooker-Feldman doctrine, there is Kreit v. Quinn, No. 16-20744 (June 13, 2017, unpublished). A state court appointed a receiver for a hospital, which then entered bankruptcy. The bankruptcy court approved a sale, a doctor strenuously  objected to the sale after the fact, and the court sanctioned the doctor for his filings. On appeal, the receiver contended that the doctor’s filings were barred by the Rooker-Feldman doctrine as a collateral, federal attack on a state court order. The doctor asked the Fifth Circuit to recognize an exception to that doctrine for orders that are void ab initio. But while noting a circuit split on the point, the Court declined to weigh in, finding that the state court had the needed authority.

objected to the sale after the fact, and the court sanctioned the doctor for his filings. On appeal, the receiver contended that the doctor’s filings were barred by the Rooker-Feldman doctrine as a collateral, federal attack on a state court order. The doctor asked the Fifth Circuit to recognize an exception to that doctrine for orders that are void ab initio. But while noting a circuit split on the point, the Court declined to weigh in, finding that the state court had the needed authority.

Lee sued for his injuries from a fall on the M/V BALTY (right). In resolving the defendant’s summary judgment motion, “[t]he district court dismissed Captain Jamison’s report solely because it was not sworn without considering Lee’s argument that Captain Jamison would testify to those opinions at trial and without determining whether such opinions, as testified to at trial, would be admissible.” The Ffith Circuit remanded for reconsideration in light of a 2010 amendment to Fed. R. Civ. P. 56 that says (as summarized by Moore’s Federal Practice): “Although the substance or content of the evidence submitted to support or dispute a fact on summary judgment must be admissible . . . , the material may be presented in a form that would not, in itself, be admissible at trial.” Lee v. Offshore Logistical No. 16-31049 (revised July 5, 2017).

Lee sued for his injuries from a fall on the M/V BALTY (right). In resolving the defendant’s summary judgment motion, “[t]he district court dismissed Captain Jamison’s report solely because it was not sworn without considering Lee’s argument that Captain Jamison would testify to those opinions at trial and without determining whether such opinions, as testified to at trial, would be admissible.” The Ffith Circuit remanded for reconsideration in light of a 2010 amendment to Fed. R. Civ. P. 56 that says (as summarized by Moore’s Federal Practice): “Although the substance or content of the evidence submitted to support or dispute a fact on summary judgment must be admissible . . . , the material may be presented in a form that would not, in itself, be admissible at trial.” Lee v. Offshore Logistical No. 16-31049 (revised July 5, 2017).

Total Gas, the American subsidiary of the large French energy concern, sued for a declaratory judgment that FERC could not impose certain penalties under the Natural Gas Act. But while FERC had begun an administrative proceeding against Total, that case had to proceed through several more steps before any penalty would be assessed. Accordingly, the dispute was not ripe for adjudication. The “step by step” analysis of ripeness in this case appears to be of general applicability to other cases involving conditions precedent. Total Gas v. FERC, No. 16-20642 (June 8, 2017).