Now that a Texas trial-court opinion has issued about deporting suspected Venezuelan gang members, the issue appears headed to the Fifth Circuit.

Now that a Texas trial-court opinion has issued about deporting suspected Venezuelan gang members, the issue appears headed to the Fifth Circuit.

Category Archives: General Court Information

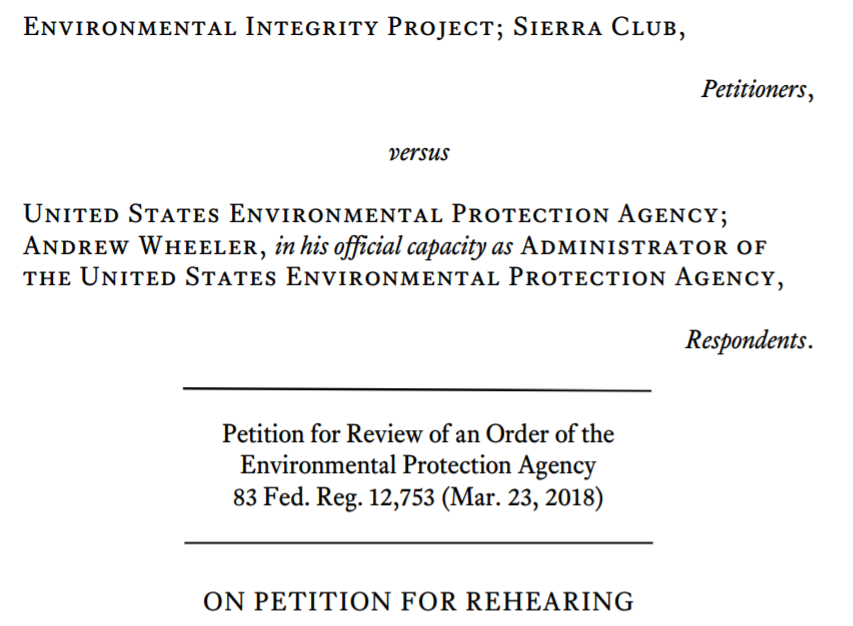

The question whether an administrative agency has unfairly “changed the rules” is central in many challenges to regulations. On April 2, the Supreme Court addressed a particularly hard-fought dispute about that issue in FDA v. Wages & White Lion Investments, LLC, a case about the FDA’s denial of marketing authorization for flavored e-cigarette products.

The question whether an administrative agency has unfairly “changed the rules” is central in many challenges to regulations. On April 2, the Supreme Court addressed a particularly hard-fought dispute about that issue in FDA v. Wages & White Lion Investments, LLC, a case about the FDA’s denial of marketing authorization for flavored e-cigarette products.

The en banc Fifth Circuit held that the FDA acted arbitrarily and capriciously by applying different standards than those stated in its predecisional guidance documents, and by failing to review marketing plans previously deemed critical.

The Supreme Court held that the FDA’s denial orders were consistent with its predecisional guidance about scientific evidence, comparative efficacy, and device type. The Court concluded that the FDA’s guidance documents did not commit to any specific type of study, and that the FDA’s requirement for manufacturers to compare their flavored products to tobacco-flavored products was a natural consequence of its guidance. No. 23-1038 (U.S. Apr. 2, 2025).

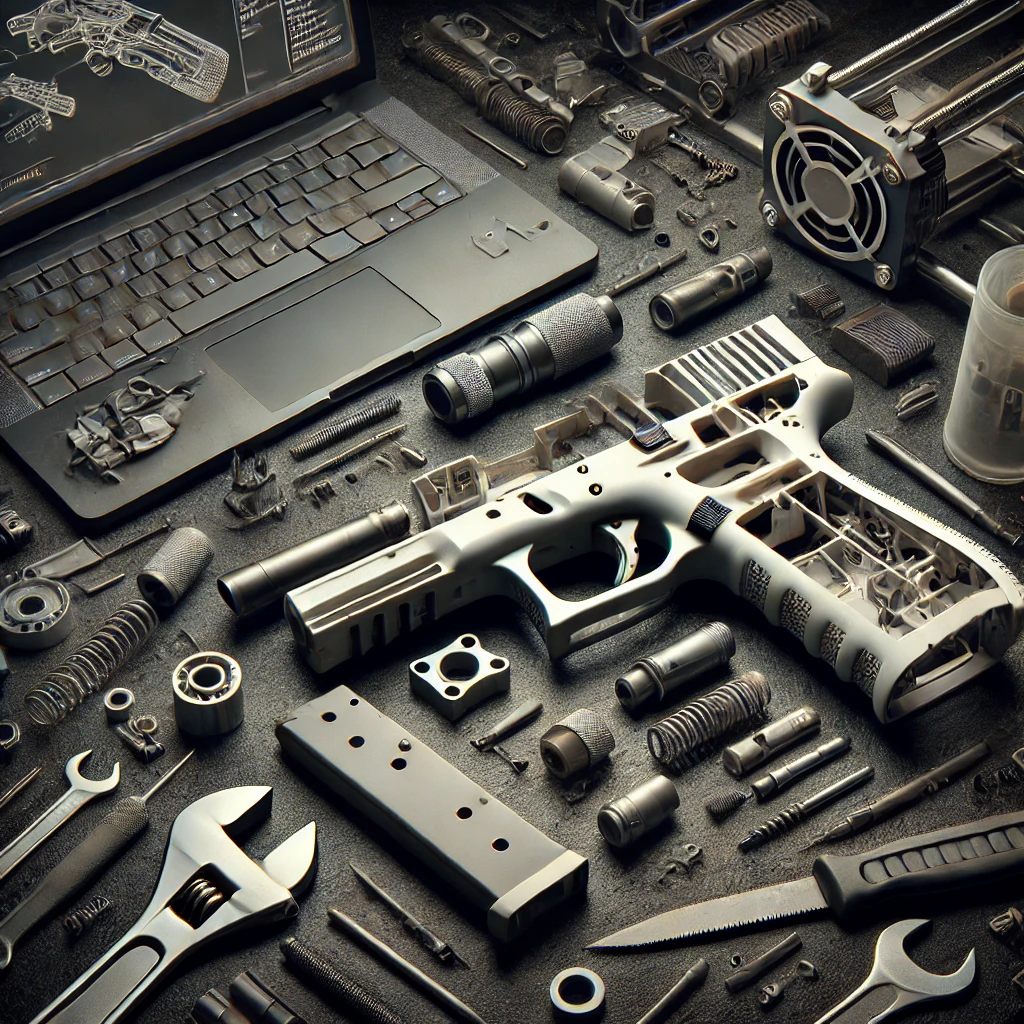

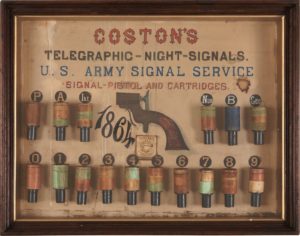

The Supreme Court today reversed the Fifth Circuit’s invalidation of an ATF regulation about “ghost guns,” noting that the relevant statute applied to “any weapon (including a starter gun) which will or is designed to or may readily be converted to expel a projectile by the action of an explosive.”

The Supreme Court today reversed the Fifth Circuit’s invalidation of an ATF regulation about “ghost guns,” noting that the relevant statute applied to “any weapon (including a starter gun) which will or is designed to or may readily be converted to expel a projectile by the action of an explosive.”

That grant of authority is readily distinguished from last Term’s opinion in Cargill v. Garland, which involved a statute focused on a specific type of firing mechanism.

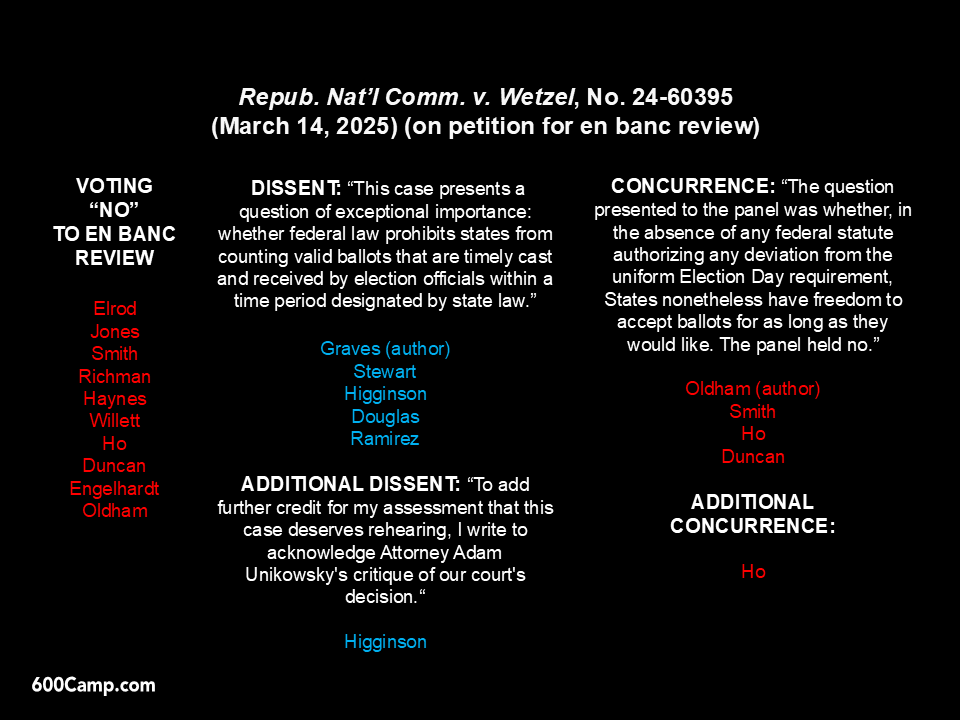

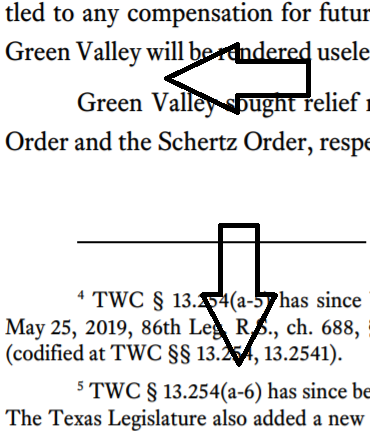

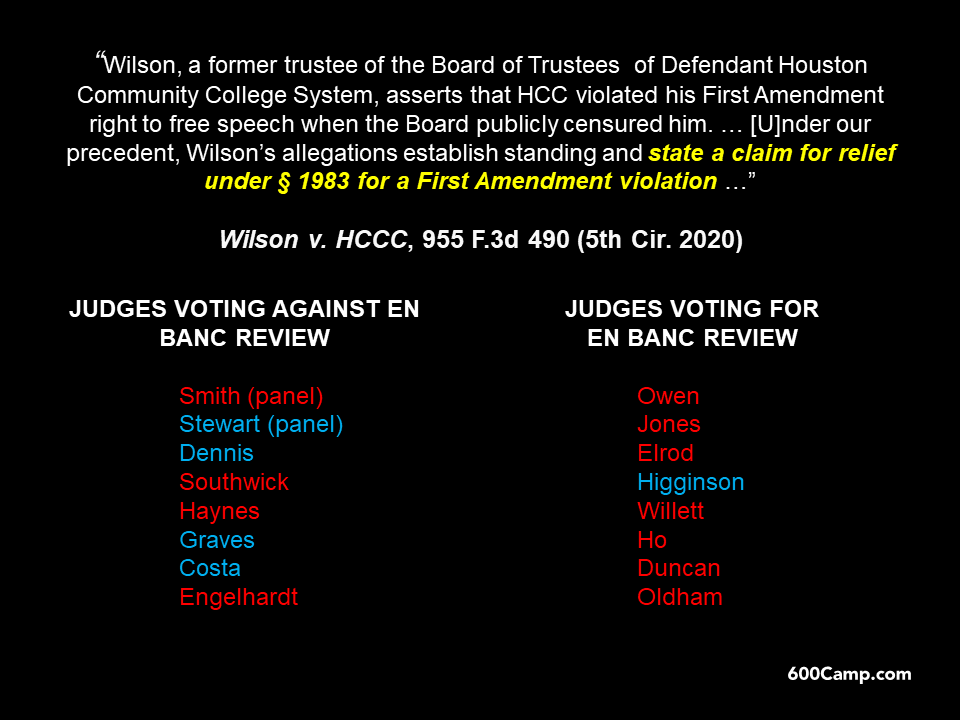

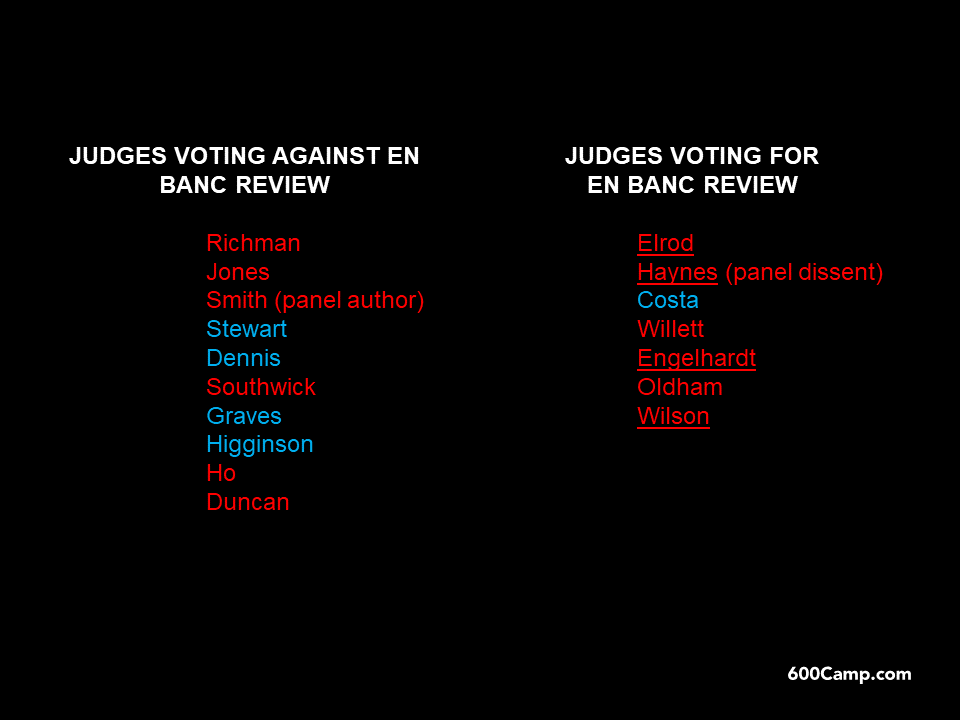

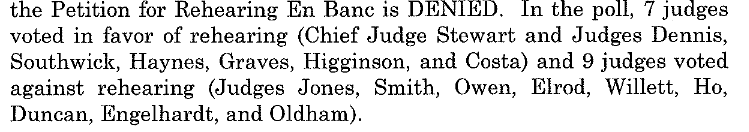

The recent vote against en banc review in Repub. Nat’l Comm. v. Wetzel, a case about the acceptable time frame for counting mail-in ballots, produced this configuration of votes and opinions:

The en banc Fifth Circuit recently denied review of Repub. Nat’l Comm. v. Wetzel – a panel opinon in a larger tradition of conservative distaste for mail. A dissent by Judge Higginson favorably noted commentary on the panel opinion, which draws an interesting distinction among (1) the parties’ briefs; (2) amicus submissions; and (3) public commentary, whether by academics or practioners (or earnest bloggers):

We benefit from lawyer insight and criticism. Though we receive amicus curiae briefs less frequently than the Supreme Court, they provide primary opportunity for non-party lawyers to give insight, albeit with stringent requirements. It is rarer that topflight lawyers, like Unikowsky, have time to offer scholarly critique of a case neither he, nor Bernstein, was retained to handle. Chief Justice Roberts recently reminded that “public engagement with the work of the courts results in a better-informed polity and a more robust democracy.” It is for this reason that the judiciary depends on lawyers, not just as party advocates, but also for all forms of engagement with courts. “[I]nformed criticism” of court opinions from lawyers unaffiliated with the parties is in that vital tradition.

I explored the interplay between non-litigation sources of information and the party-presentation principle in this Cornell Law Review article last year.

At a recent BAFFC CLE program at the Texas A&M Law School in Fort Worth, the Fifth Circuit’s able clerk Lyle Cayce presented the most recent version of his office’s “Appeal Flowchart.” It’s a top-notch reference about that Court, and a good general guide to the workinsg of all appellate courts.

Texas Bankers Association v. CFPB presents a sign of the times, with the change of Presidential administrations: “A new President was inaugurated January 20, 2025. This case had already been set to be orally argued on February 3, 2025. The morning of oral argument, CFPB notified the court that “[c]ounsel for the CFPB has been instructed” by new leadership “not to make any appearances in litigation except to seek a pause in proceedings.” Accordingly, although both sides appeared in court as scheduled, only Texas Bankers addressed the merits.” No. 24-40705 (Feb. 7, 2025). A temporary stay was then ordered to allow the CFPB to finalize its decisionmaking about the case.

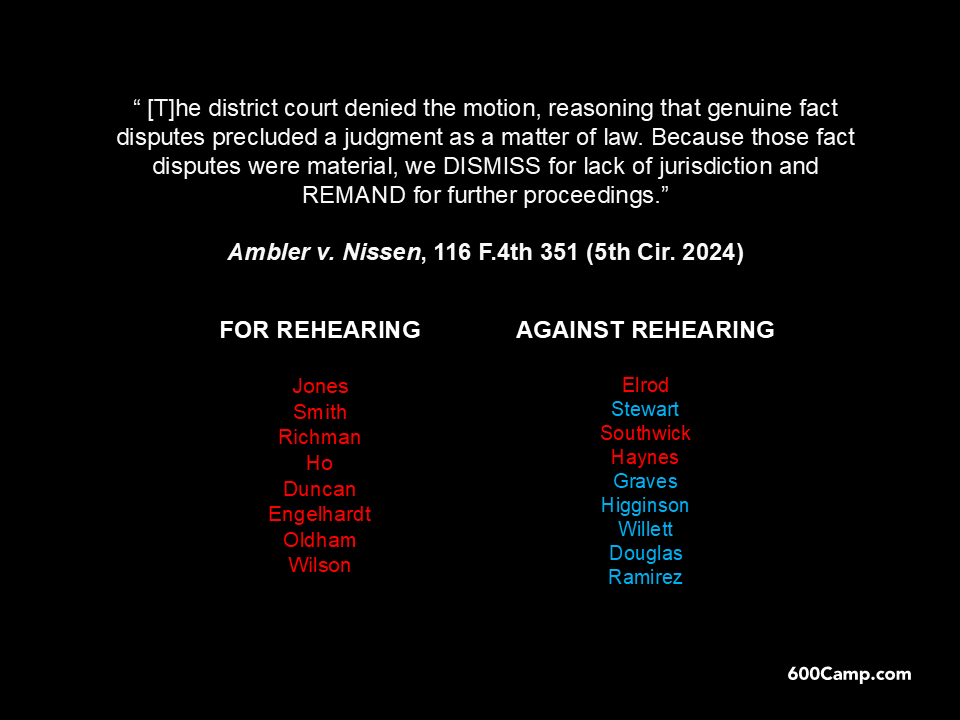

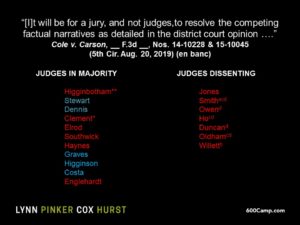

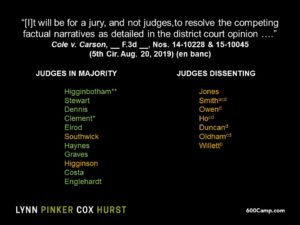

In Ambler v. Nissen, a Fifth Circuit panel dismissed a qualified-immunity appeal because of the materiality of the fact issues presented. The full court denied en banc review in a close vote:

Stone v. Graham, 449 U.S. 39 (1980), holds:

“Posting of religious texts on the wall serves no such educational function. If the posted copies of the Ten Commandments are to have any effect at all, it will be to induce the schoolchildren to read, meditate upon, perhaps to venerate and obey, the Commandments. However desirable this might be as a matter of private devotion, it is not a permissible state objective under the Establishment Clause.“

Unsurprisingly, then, the Fifth Circuit voted 14-3 on December 30 to reject an overly enthuastic application for en banc hearing in Roake v. Brumley – the challenge to a Louisiana law about display of the Ten Commandments that is flatly inconsistent with the above Supreme Court holding.

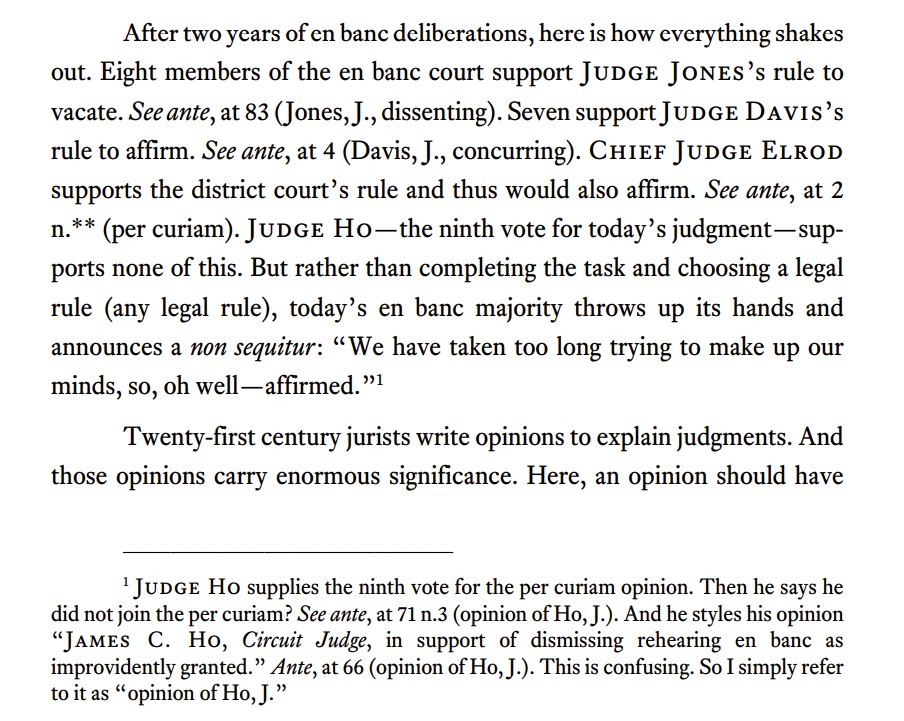

Judge Oldham’s thoughtful dissent from the recent wreckage of an en banc proceeding provides fascinating historical background about courts’ traditional focus on decisions rather than opinions. That basic concept about the operation of appellate courts is useful in distinguishing holding from dicta, identifying the appropriate scope of appellate review, and clarifying questions about the law of the case / res judiciata effect of earlier judgments.

Judge Oldham’s thoughtful dissent from the recent wreckage of an en banc proceeding provides fascinating historical background about courts’ traditional focus on decisions rather than opinions. That basic concept about the operation of appellate courts is useful in distinguishing holding from dicta, identifying the appropriate scope of appellate review, and clarifying questions about the law of the case / res judiciata effect of earlier judgments.

By including Roman courts in its historical review, the opinion reminds how much the American system has borrowed from the civilian tradition – a point of particular interest in Texas, where opinions from the 1840s by the Republic of Texas Supreme Court vividly illustrate the jostling between the English/American and Spanish/French systems on issues of property law at that time.

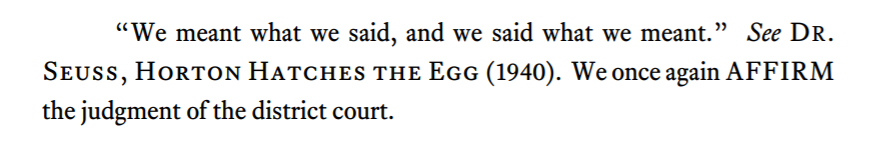

Lengthy en banc deliberation produced a one-paragraph, per curiam affirmance in Environment Texas Citizen Lobby, Inc. v. ExxonMobil Corp., a long-running challenge to a $20 million environmental fine. Judge Oldham’s dissent summarizes the bewildering array of votes and opinions:

Lengthy en banc deliberation produced a one-paragraph, per curiam affirmance in Environment Texas Citizen Lobby, Inc. v. ExxonMobil Corp., a long-running challenge to a $20 million environmental fine. Judge Oldham’s dissent summarizes the bewildering array of votes and opinions:

This week, the Eastern District of Texas enjoined a sweeping set of Treasury regulations about disclosure of beneficial ownership, concluding that the Corporate Transparency Act and related regulations exceeded Congress’s constitutional powers. The Northern District of Texas rejected Boeing’s plea bargain of charges related to the 737 MAX debacle, concluding that inappropriately required consideration of race in selecting the monitors for a program that would administer Boeing’s compliance with agreed obligations going forward. The Boeing ruling may yet be resolved in the trial court, as the judge asked the parties to report back in 30 days, but the CTA case will certainly be headed to the Fifth Circuit soon.

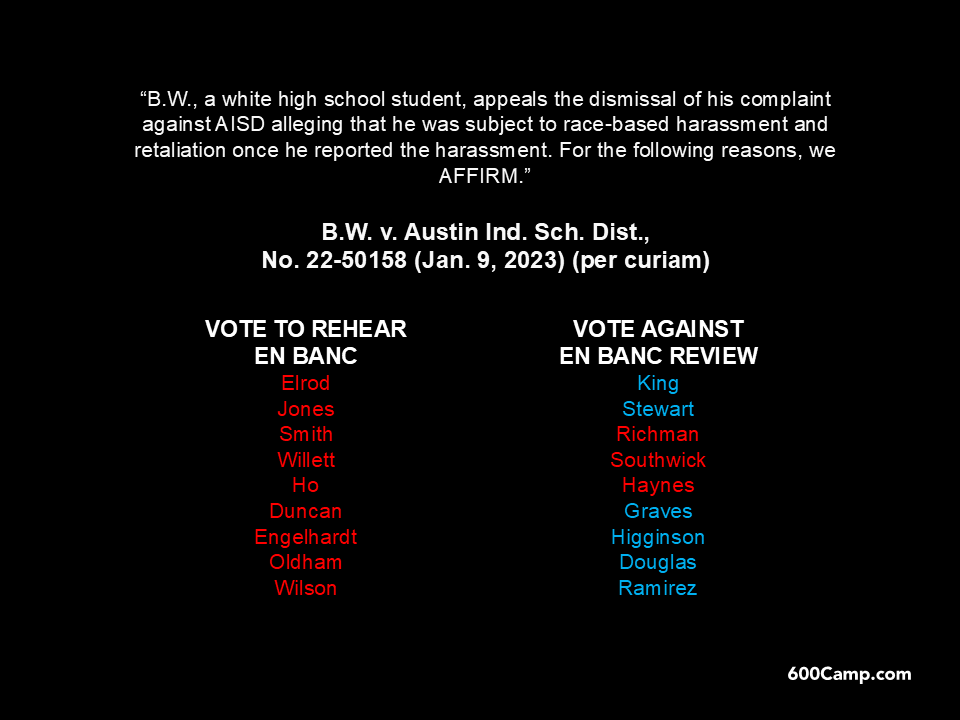

A recent en banc vote produced an unusual 9-9 tie (and thus, affirmance of the panel opinion) because a senior judge sat on the relevant panel:

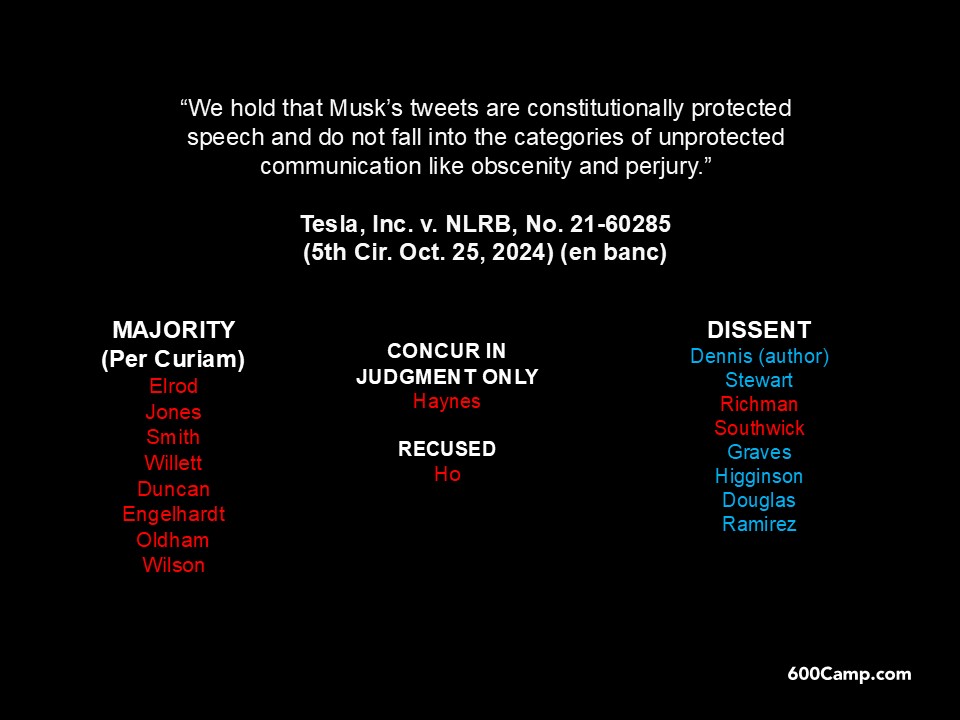

In a per curiam opinion joined by eight judges, the Fifth Circuit held in Tesla v. NLRB that an NLRB decision about unfair labor practices by Tesla would be vacated and remanded for further proceedings:

We hold that Musk’s tweets are constitutionally protected speech and do not fall into the categories of unprotected communication like obscenity and perjury. And the Board does not dispute the general rule that it (like every other part of the Government) is powerless to delete protected speech.

But nine other judges didn’t join that opinion. As detailed below, Judge Haynes concurred in the judgment only, and eight judges joined a dissent. So what the NLRB is supposed to do on remand is not entirely clear.

Quoted in a provocative new article in Mother Jones about the Fifth Circuit, I point out that it’s the venue of choice these days for administrative-law disputes.

Hon. Jennifer Walker Elrod has taken office as the new Chief Judge of the Fifth Circuit, succeeding Hon. Priscilla Richman. The Texas Lawbook has a good story on this “changing of the guard” for this critical leadership role. The new Chief tells the Lawbook:

Hon. Jennifer Walker Elrod has taken office as the new Chief Judge of the Fifth Circuit, succeeding Hon. Priscilla Richman. The Texas Lawbook has a good story on this “changing of the guard” for this critical leadership role. The new Chief tells the Lawbook:

“I believe that we are all in this endeavor together to uphold our Constitution and try to follow the rule of law and this enterprise works best when everyone gets to participate and have their say … And we can learn from each other if we’re all at liberty to engage. … I also believe iron sharpens iron … by learning what others who think differently believe, and what the basis for that belief is, that can help you to better reinforce your view, or perhaps, to change your mind.”

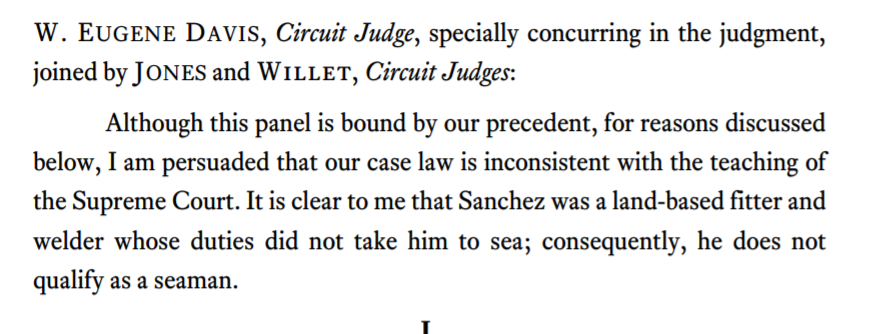

Unsurprisingly, given all three judges’ discomfort with the Fifth Circuit precedent that dictated the panel holding in Abraham Watkins v. Festeryga, that case will be considered by the en banc court. The issue, as summarized by the panel majority, is this:

Edward Festeryga, an attorney embroiled in a dispute with his former law firm, wants this case heard in federal court and contends we have appellate jurisdiction over the district court’s remand order because waiver is neither an issue of subject-matter jurisdiction nor a defect in removal procedure under 28 U.S.C. § 1447(c). We agree, but our 40-plus-year-old precedent provides otherwise, holding that a waiver-based remand order is jurisdictional under § 1447(c) and thus unappealable under § 1447(d).

While no longer in the academy, the capable Rory Ryan offered this insightful analysis of this case on X.

Dickson v. Janvey, a dispute about the scope of an anti-litigation injunction, offers two basic reminders about the process of separating holding from dicta:

Dickson v. Janvey, a dispute about the scope of an anti-litigation injunction, offers two basic reminders about the process of separating holding from dicta:

- Not discussed, likely not holding. “[W]e have previously held that a district court’s power over a receivership enables it to enjoin third parties or non-parties from pursuing certain claims involving the res of the receivership estate. But our statements in those cases implicated the equitable remedies available to the district court and not its jurisdiction. No one objected to personal jurisdiction in those cases, likely because any such objection would have been frivolous. But even if there were a latent in personam defect in those cases, our silence could never be construed as an implicit holding.” (citations and footnotes omitted).

- Not necessary, likely not holding. “Hall suggested in dicta that federal courts may enter in rem injunctions in aid of a previous in rem judgment. It is unclear to us what the Hall court meant by this dicta. But … the Hall court’s reference to an ‘inrem injunction’ was unnecessary to its decision. Federal jurisdiction in that

case was not in rem. So the court’s in rem discussion was nonbinding dicta.” (citations omitted).

No. 23-10726 (Aug. 9, 2024) (Enthusiasts of dicta-holding distinctions will recall that courts have discretion whether to give effect to obiter dicta–an unnecessary but thoughtful statement–under the circumstances of a particular case.)

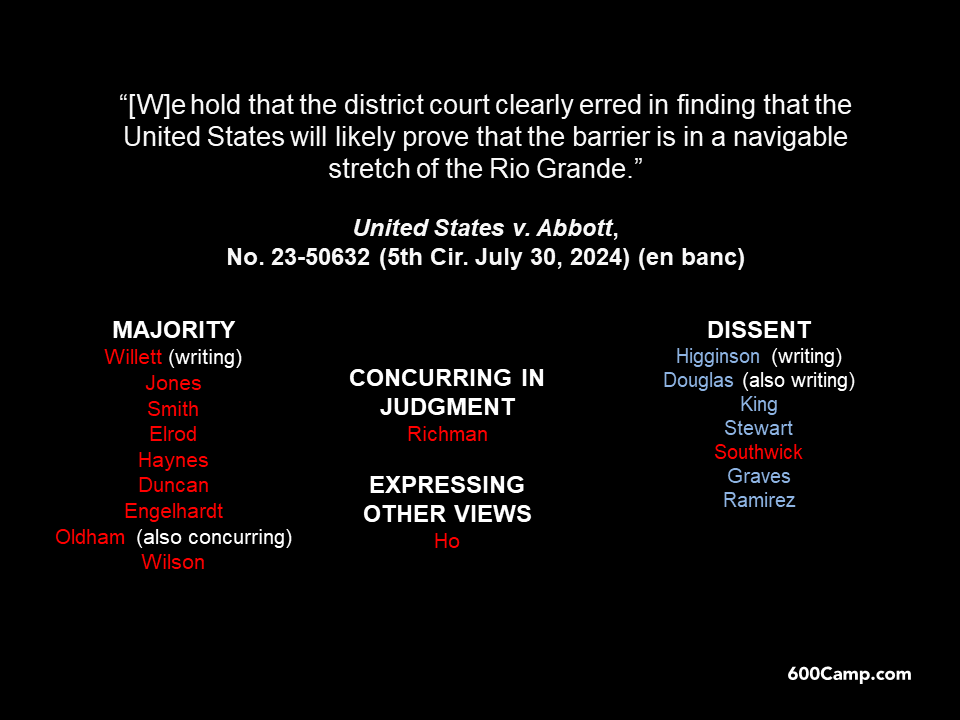

The en banc court has ruled for Texas in the ongoing “border buoy” dispute, with a breakdown of votes as follows:

After another Supreme Court term featuring reversals of the Fifth Circuit on standing grounds in high-profile cases, I wrote this op-ed in today’s Dallas Morning News about that recurring issue.

Late last week, Judge Ada Brown from the Northern District of Texas held that the FTC exceeded its authority by its new rule about noncompetition agreements, granted a preliminary injunction, and set the matter for trial in late August. Notably, as of now, the relief granted does not include a nationwide injunction about the rule.

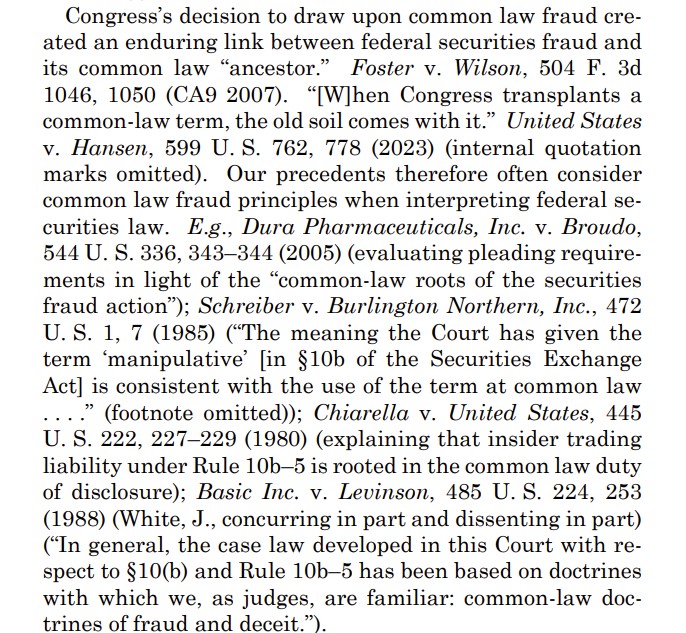

Much ink will be spilled over the Supreme Court’s use of history in resolving cases this term about the Appropriations Clause, possession of firearms by dangerous people, and the SEC’s internal courts. One key point in Jarkesy is the extent to which a word, used in the 1790s, has the same general meaning today. As the below quote illustrates, “fraud is fraud” oversimplifies the Supreme Court’s holding – but not by much. “Fraud” in today’s commercial law means pretty much what it did in the 1790s. Other words, such as “economy,” are not so easily transported through time, and that reality calls for caution in seeing Jarkesy as providing broad support for some other “originalist” ideas.

On remand from the Supreme Court after that court’s rejection of a challenge to the CFPB’s funding based on the Appropriations Clause, the Fifth Circuit issued a short judgment reflecting that ruling. Interestingly, the judgment expressly identifies the rehearing deadline while striking an earlier 28j filing by the plaintiff:

That filing is no longer available online, but the CFPB’s response suggests that the parties dispute the scope and effect of the Supreme Court’s mandate–and what that may mean for the other challenges to the CFPB presented in this case.

That filing is no longer available online, but the CFPB’s response suggests that the parties dispute the scope and effect of the Supreme Court’s mandate–and what that may mean for the other challenges to the CFPB presented in this case.

As I argued a year ago, more than once, the Supreme Court holds 9-0 this morning that the mifepristone plaintiffs lacked standing:

Governor Abbott has appointed the three inaugural members of the new Fifteenth Court of Appeals: Hon. Scott Brister, presently of Hunton Andrews Kurth, well-known statewide from his service on the Texas Supreme Court, and the author of City of Keller v. Wilson, 168 S.W.3d 802 (Tex. 2005); Hon. April Farris, of the First Court of Appeals; and Hon. Scott Field, of the 480th District Court in Williamson County, and formerly of the Third Court of Appeals.

As noted previously, the Fifth Circuit denied en banc review by an 8-8 vote in a contentious forum dispute. The breakdown of the votes is follows (the entire panel majority opinion appears in the chart, and the panel dissent is reproduced as an exhibit to the dissent from the denial of en banc review):

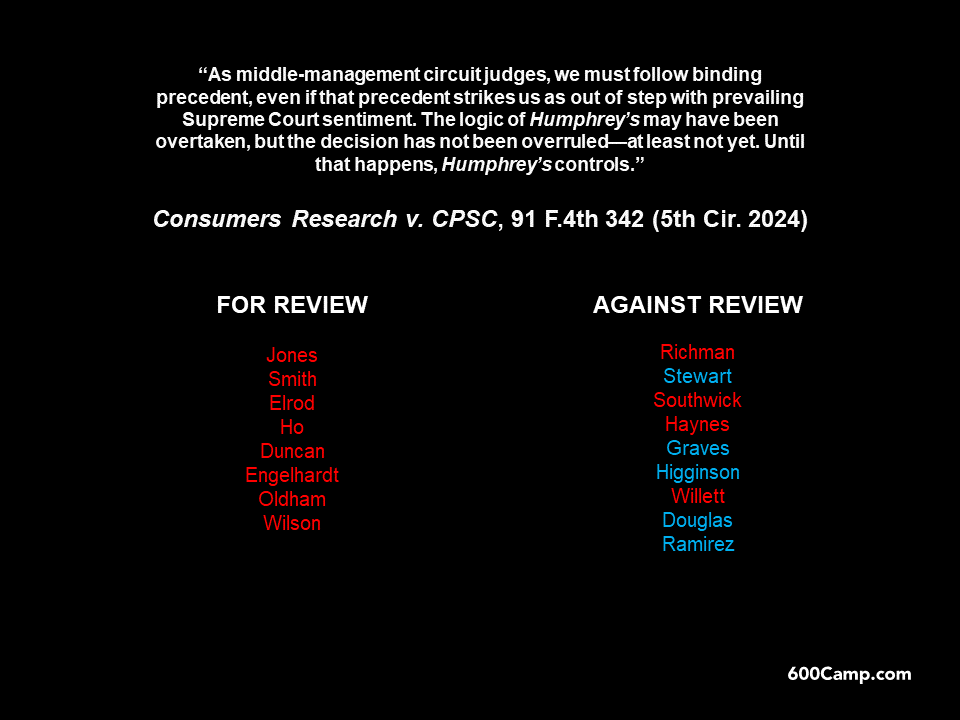

The Fifth Circuit’s recent en banc vote in Consumers’ Research v. CPSC, an unsuccessful constitutional structure to the Consumer Product Safety Commission in light of recent Supreme Court precedent, is summarized in the below chart. The vote was accompanied by a concurrence and two dissenting opinions.

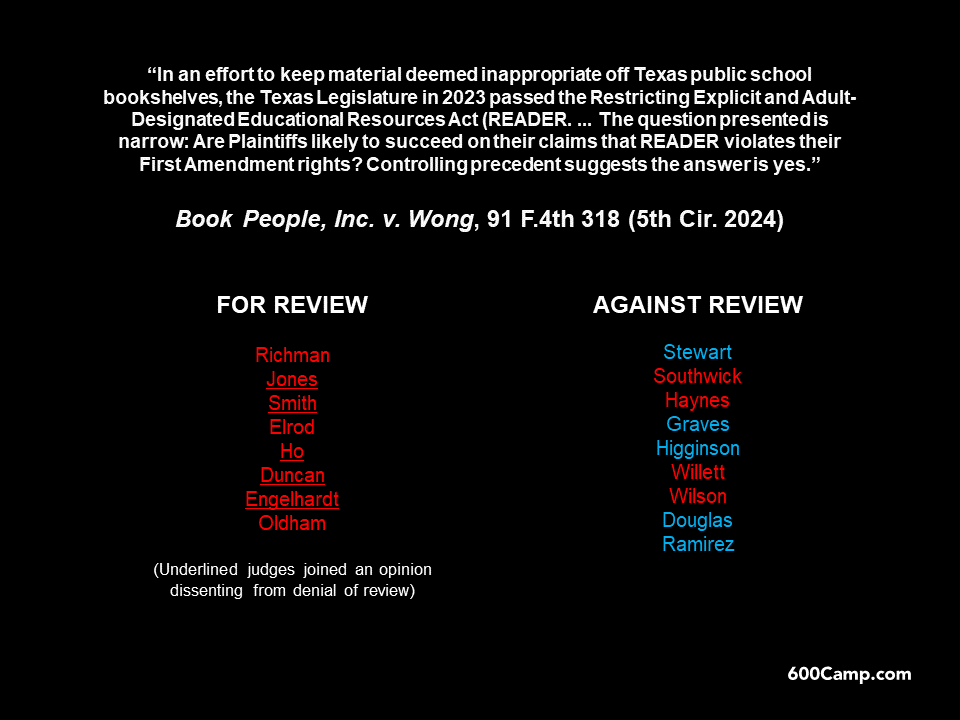

The Fifth Circuit’s recent en banc vote in Book People, Inc. v. Wong, a successful constitutional challenge to a prior-restraintish law involving the content of books in school libraries, is summarized in the below chart:

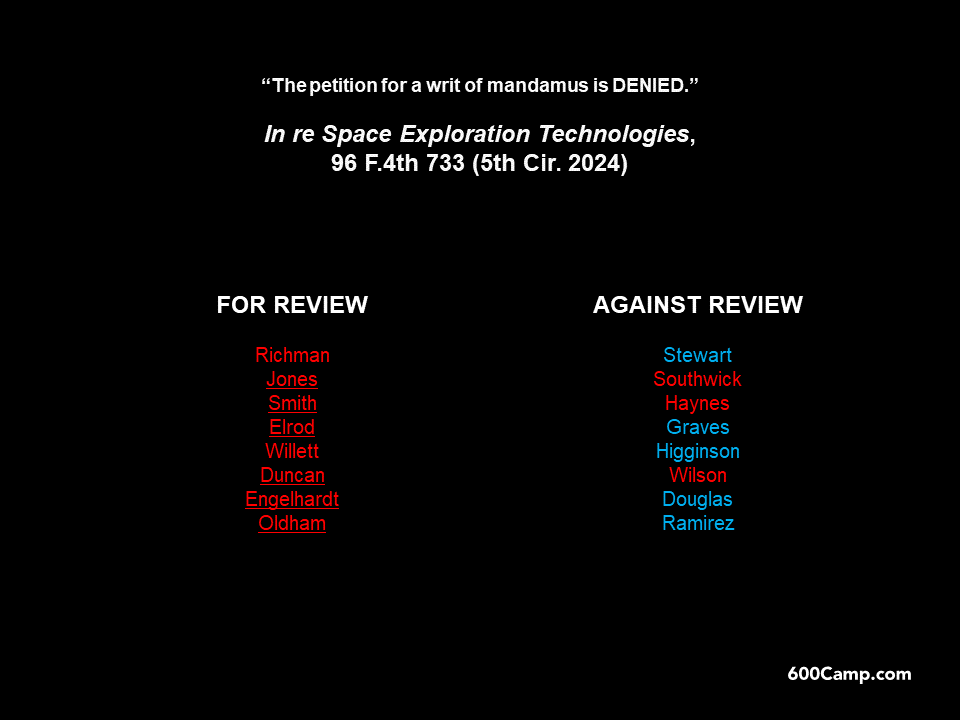

Resolving another of the simmering venue disputes that have drawn considerable attention in recent weeks, the full Fifth Circuit denied en banc review (an 8-8 tie vote) of the denial of mandamus relief in In re SpaceX – a challenge to the district court’s order that transferred a dispute between SpaceX and the NLRB to the Central District of California.

I hope you find this cross-post from 600 Commerce to be informative!

The most recent Advocate (the quarterly publication of the State Bar of Texas Litigation Section) has several articles about how the new Fifteenth Court of Appeals will get off the ground. I have a short piece on where the new court is likely to look for precedent, since it will have none of its own to start. I hope you find it useful in thinking about this important new appellate forum.

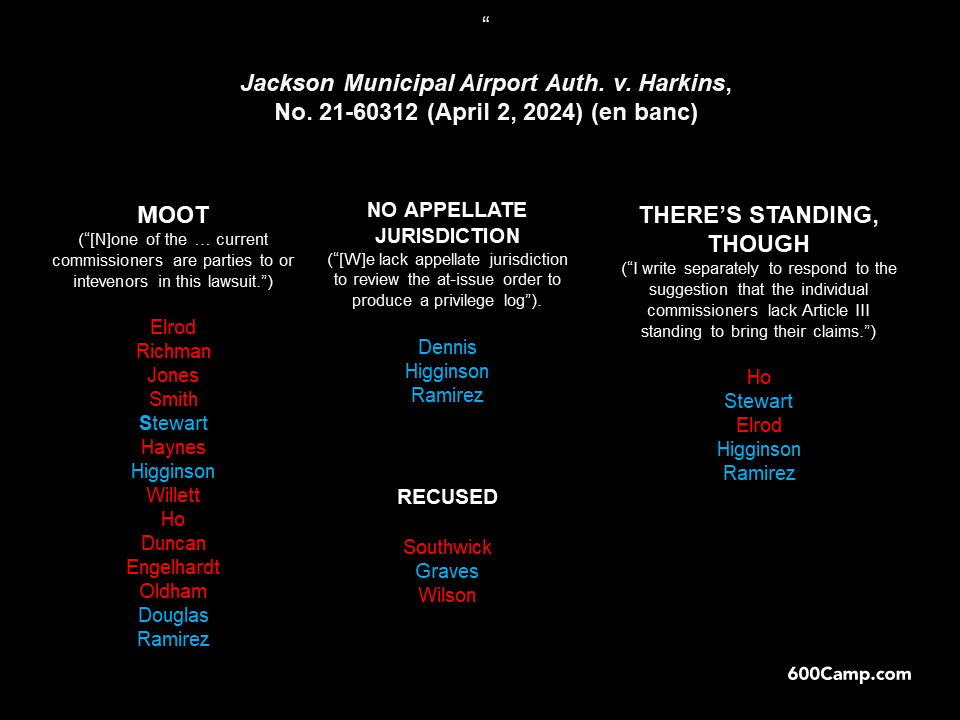

Long-running litigation about control of the Jackson airport led to the en banc court holding on April 2 that the appeal was moot. A breakdown of the viewpoints appears below:

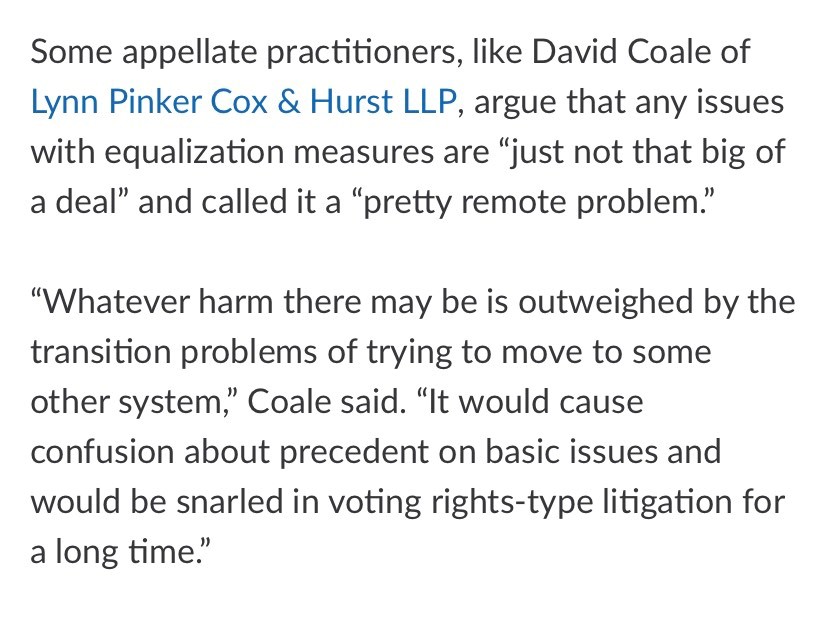

Several disputes about inter-circuit venue transfers are ongoing (I was recently interviewed by Bloomberg about this phenomenon):

Several disputes about inter-circuit venue transfers are ongoing (I was recently interviewed by Bloomberg about this phenomenon):

- SpaceX. In a dispute between SpaceX and the NLRB, the Fifth Circuit is considering whether to review a transfer order en banc. The NLRB recently filed its response to an unusual order from the panel asking the NLRB to explain several actions taken earlier in the proceedings. The gist of the NLRB’s response was:

Only one court may have jurisdiction at a time. The transferee court was notobliged to follow the February 26 order, and zealous advocacy required the NLRB to present its legal arguments as to why it should not be followed to the Central District of California. Thus, the NLRB urged that court, not to ignore this Court’sorder, but to acknowledge it and respectfully decline retransfer.

- CFTC. In a dispute involving the Commodities Futures Trading Commission, the District of the District of Columbia has received the district court’s request to return the case, along with briefing and argument from the parties about the appropriate next step, and as of April 6 continued to have that request under consideration.

- CFPB. In a dispute involving the CFPB and a new rule about credit-card late fees, a 2-1 panel decision granted mandamus relief on April 5–after a case had been transferred to the District of the District of Columbia, concluding:

Because the Chamber had a short window of time to either (1) comply with the Final Rule, or (2) seek a preliminary injunction, the district court’s inaction amounted to an effective denial of the Chamber’s motion for a preliminary injunction. That effective denial is properly before us on appeal. The district court lacked jurisdiction to transfer the case after this appeal was docketed because doing so would alter its status. … The district court is ORDERED to reopen the case and to give notice to D.D.C. that its transfer was without jurisdiction and should be disregarded.

- CFPB dissent. The dissent in the CFPB case concluded: “For the foregoing reasons, I believe that the new proposition of law created by the majority is incompatible with district court discretion over docket management and prudent policing of forum shopping. Finally, I am confident the District Court for the District of Columbia will give the suggestion that it should disregard a case docketed by it its closest attention.”

- HHS. The Court has expedited argument (to May 1) of National Infusion Center v. Becerra , a challenge to the dismissal of a case about 2022 drug-reimbursement regulations on venue grounds (after the dismissal of a party for jurisdictional reasons).

A recent policy statement from the Judicial Conference of the United States recommended changes to judge-assignment practices in district courts. The statement has drawn considerable attention both pro and con; this Volokh Conspiracy post is a good summary of the “con” side. A recent letter from the Chief Judge of the Northern District of Texas says that its judges have declined to materially change that district’s judge-assignment policies.

A recent policy statement from the Judicial Conference of the United States recommended changes to judge-assignment practices in district courts. The statement has drawn considerable attention both pro and con; this Volokh Conspiracy post is a good summary of the “con” side. A recent letter from the Chief Judge of the Northern District of Texas says that its judges have declined to materially change that district’s judge-assignment policies.

After an earler (unexplained) grant of an administrative stay touched off weeks of fast-paced appellate litigation about Texas’s “SB4” immigration law, a majority of the Fifth Circuit’s merits panel denied any further stay of the trial court’s injunction against enforcement of that law. USA v. Texas, No. 24-50149 (March 26, 2024). Argument is scheduled next week; barring Supreme Court intervention, merits opinions similar to these are likely.

All eyes will be on New Orleans this morning, for the (videoconferenced) arguments in United States v. Texas, where last night’s order suggests a 2-1 decision will be forthcoming that continues to bar enforcement of Texas’s SB4 during the pendency of its appeal. The Supreme Court will likely be asked about the resulting order, whatever it may be.

You can tell your argument isn’t working when the Fifth Circuit summarizes it as follows:

You can tell your argument isn’t working when the Fifth Circuit summarizes it as follows:

“SCW’s last remaining counterargument is that it should be able to pick and choose different clauses from the LSAA and the Grant Agreement and then mush them together to demand money from debtors.”

and when the Court begins its opinion:

“Widowed octogenarians Iris Calogero and Margie Nell Randolph received dunning letters from a Louisiana law firm … .”

Calogero v. Shows, Cali & Walsh, LLP, No. 22-30487 (March 15, 2024). More substantive review to follow in the week ahead!

The Judicial Conference has voted to strenghen its policy about random case assignment, as set forth here.

The Fifth Court ordered a rare reversal for a new trial because of improper closing argument in Clapper v. American Realty Investors. The Court summarized the improper statements as “employ[ing] nearly every type of improper argument identified by our court, including highly improper and personal attacks against opposing counsel, remarks about Clapper’s wealth, a discussion of matters not in the record, insinuations that Clapper had lower moral standards because he was from Michigan, and suggestions of Clapper’s bad motives through counsels’ opinion.”

The Fifth Court ordered a rare reversal for a new trial because of improper closing argument in Clapper v. American Realty Investors. The Court summarized the improper statements as “employ[ing] nearly every type of improper argument identified by our court, including highly improper and personal attacks against opposing counsel, remarks about Clapper’s wealth, a discussion of matters not in the record, insinuations that Clapper had lower moral standards because he was from Michigan, and suggestions of Clapper’s bad motives through counsels’ opinion.”

The Court concluded: “We remind all practitioners in our court that zealous advocacy must not be obtained at the expense of incivility. As Judge Reavley aptly explained, ‘Although earnest, forceful, and devoted representation is both zealous and proper, Rambo and kamikaze lawyers lead themselves and their clients to zealous extinction.'” No. 21-10805 (March 8, 2024).

Notably, footnote two dismisses several arguments about preservation, concluding that “[t]he serious nature of the argument in this trial … indicates that substantial justice requires a new trial ….”

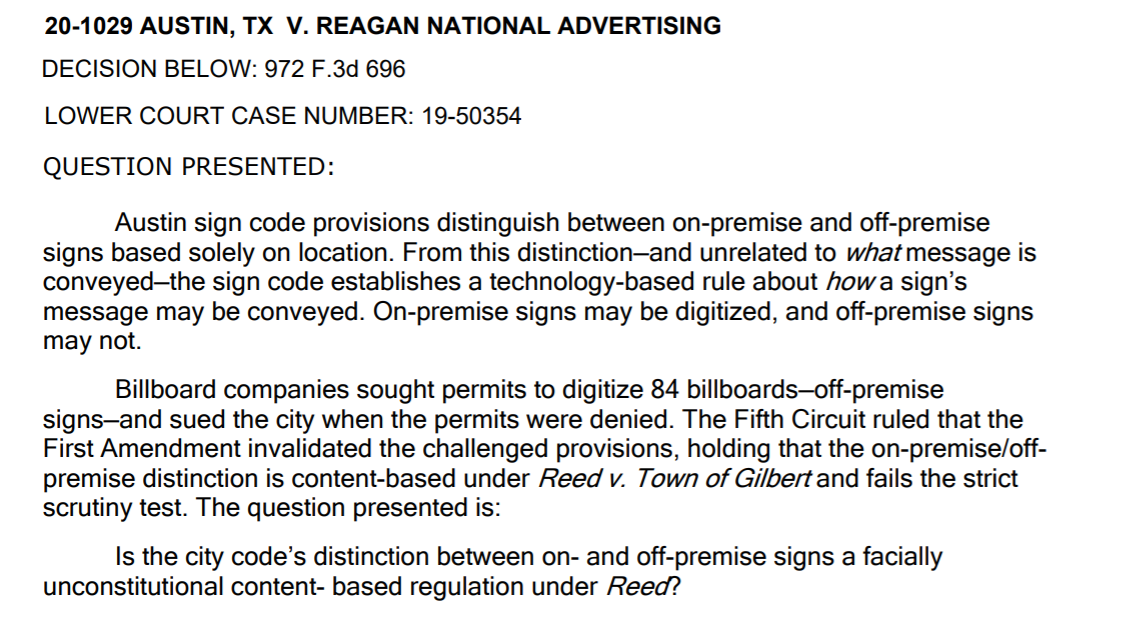

Together with Marcy Greer, I recently gave an update about recent Fifth Circuit cases at the first-ever Central Texas Bench-Bar meeting. This is our PowerPoint from the March 1 presentation.

Together with Marcy Greer, I recently gave an update about recent Fifth Circuit cases at the first-ever Central Texas Bench-Bar meeting. This is our PowerPoint from the March 1 presentation.

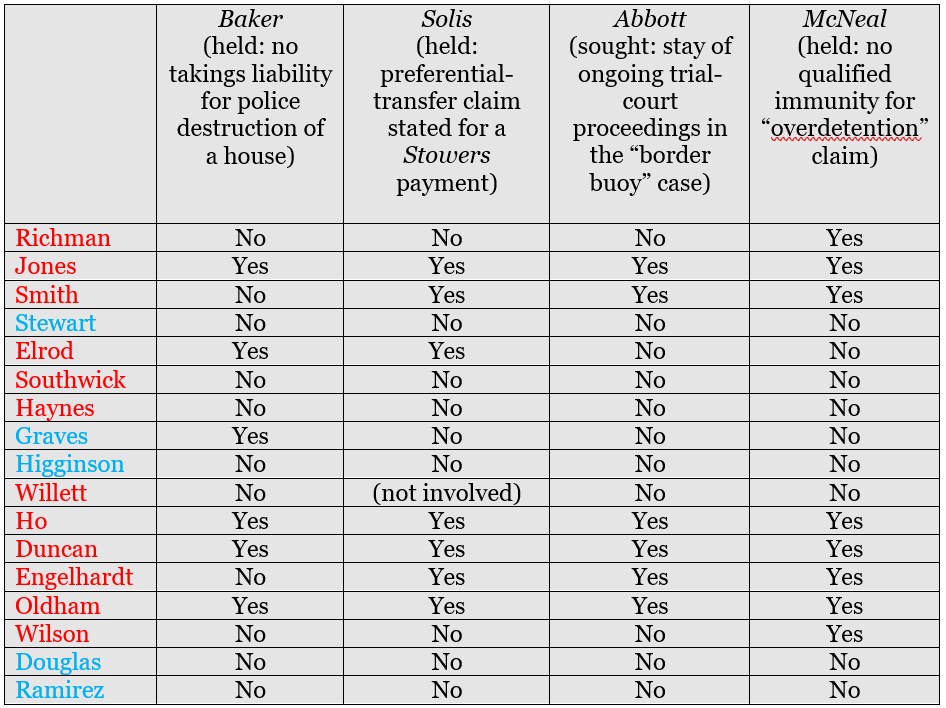

February 2024 has been a busy month for en banc votes. The recent vote by the full court about a stay in U.S. v. Abbott, as well as votes to deny en banc review of Baker (a takings case about police destruction of a home) and Solis (holding that a preferential-transfer claim was stated as to a Stowers-related payment) provided an unusual snapshot of the full court’s views on multiple issues at the same time.

Those votes are now supplemented by an 8-9 vote to deny review in McNeal v. LeBlanc, a panel opinion that denied qualified immunity in an “overdetention” case. The below chart summarizes those votes (a “yes” vote is for en banc review or issuance of a stay, as appropriate):

Judges Jones, Ho, and Oldham voted “yes” for review of each of these four cases. Judges Southwick, Haynes, Higginson, Douglas, and Ramirez voted “no” for review of each of these four cases.

Judges Jones, Ho, and Oldham voted “yes” for review of each of these four cases. Judges Southwick, Haynes, Higginson, Douglas, and Ramirez voted “no” for review of each of these four cases.

The National Court Reporters Association recently published a fascinating “white paper” about “ethical and legal issues related to the use of artificial intelligence … and digital audio recording of legal proceedings.” It’s succinct, thoughtful, and raises questions relevant to just about any area of law practice or court administration that’s touched by the influence of generative AI and related technologies.

The National Court Reporters Association recently published a fascinating “white paper” about “ethical and legal issues related to the use of artificial intelligence … and digital audio recording of legal proceedings.” It’s succinct, thoughtful, and raises questions relevant to just about any area of law practice or court administration that’s touched by the influence of generative AI and related technologies.

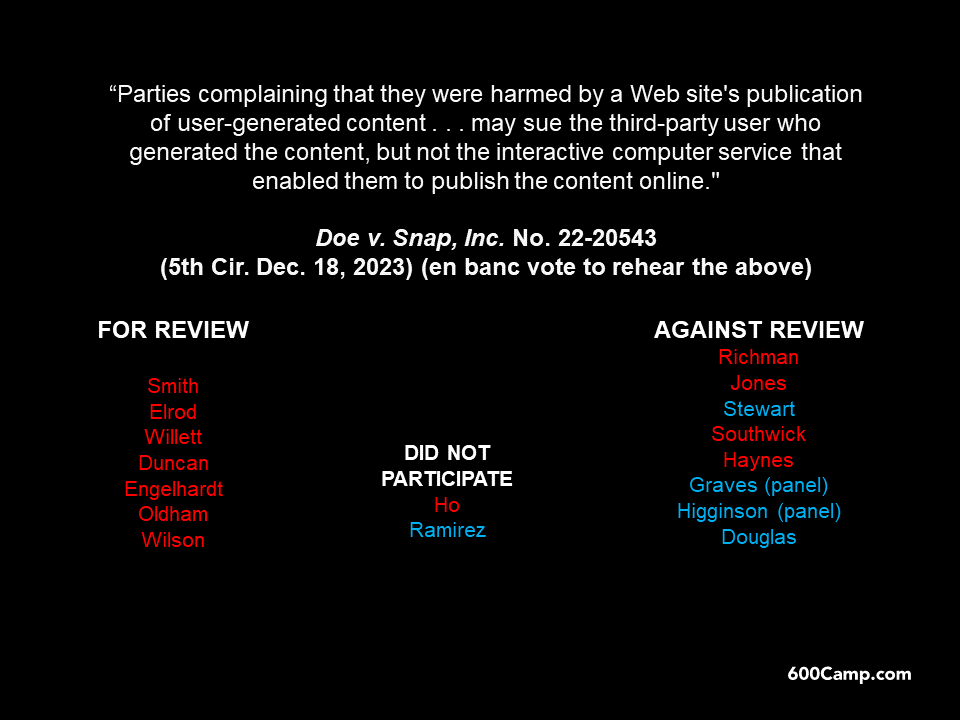

A Fifth Circuit panel applied circuit precedent to reject a liablity claim involving Snapchat in Doe v. Snap, Inc., No. 22-20543 (June 26, 2023), stating: “Parties complaining that they were harmed by a Web site’s publication of user-generated content . . . may sue the third-party user who generated the content, but not the interactive computer service that enabled them to publish the content online.” By a one-vote margin, the full court denied en banc review, as follows (notably, Edith Jones voted with the court’s Democrats to not review the panel opinion):

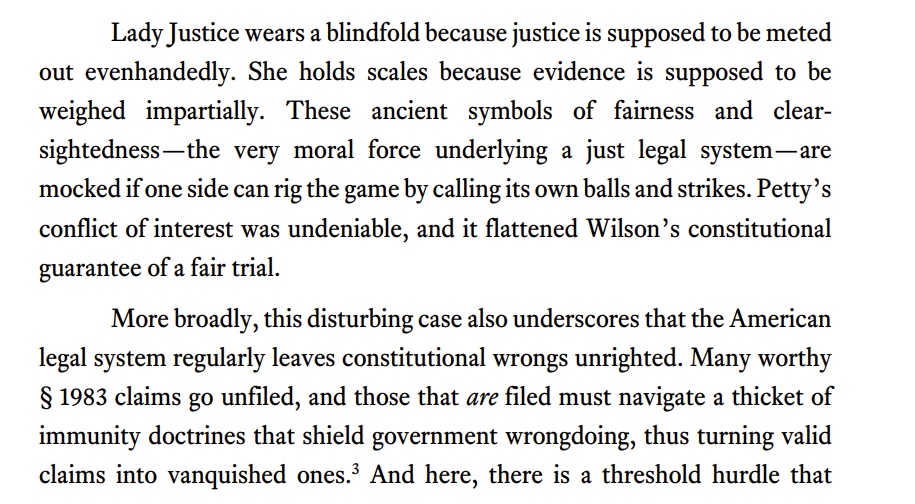

Whatever your views of the remarkable civil-rights issue presented by Wilson v. Midland County (the intersection between some highly technical immunity rules and the bizarre injustice of a county employee working simultaneously for the prosecution and the courts), one can admire the deft prose of Jude Willett’s opinion:

The Senate recently confirmed Hon. Irma Ramirez of Dallas as a judge on the Fifth Circuit. When she takes office the Court will again be at a full complement of active judges.

The Senate recently confirmed Hon. Irma Ramirez of Dallas as a judge on the Fifth Circuit. When she takes office the Court will again be at a full complement of active judges.

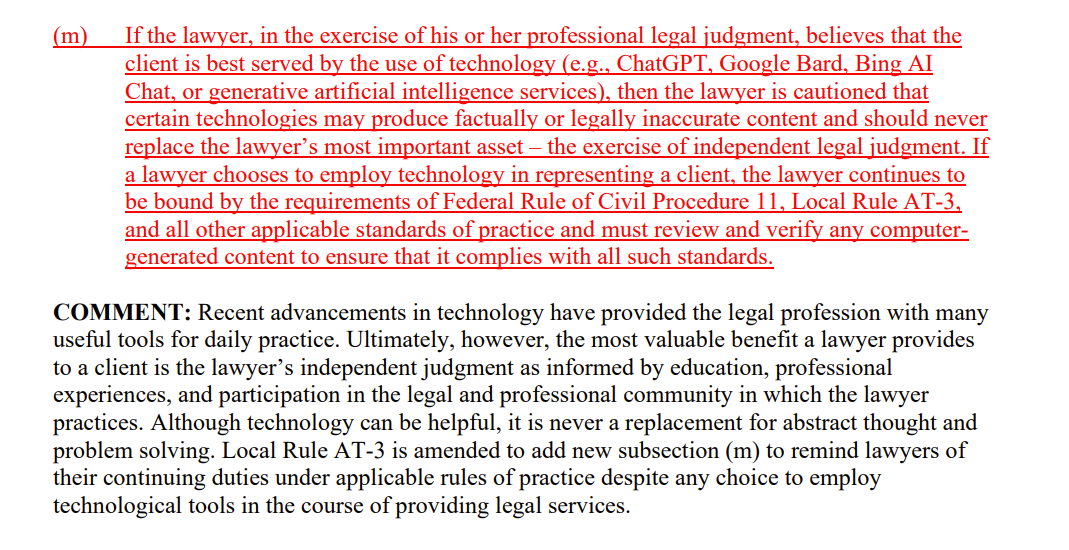

Joining other courts that have made similar additions to their local rules, the Eastern District of Texas now has new local rules dealing with the use of generative AI:

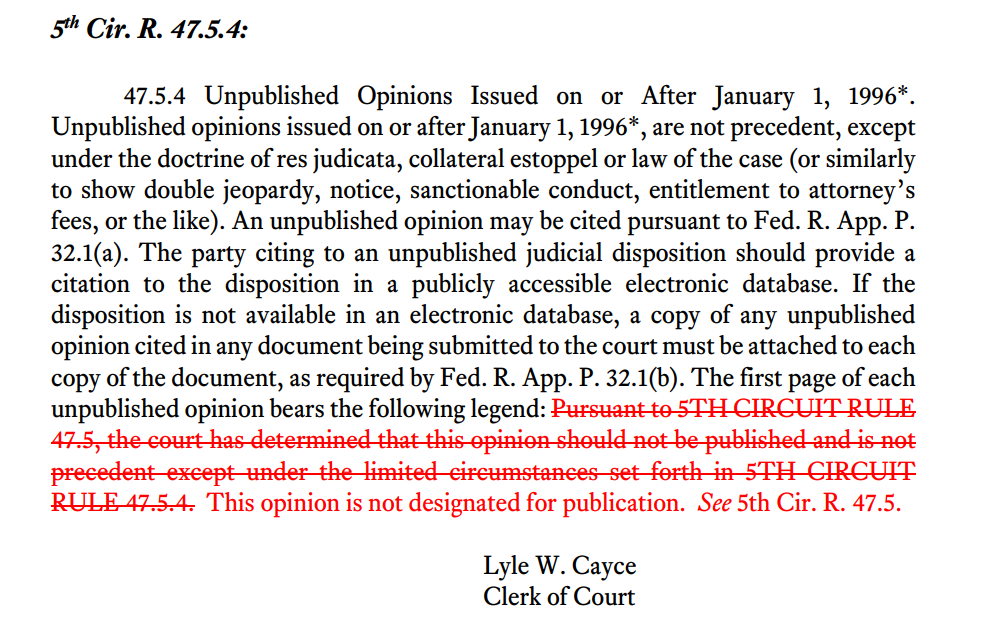

In a dissent from a recent, close en banc vote in a criminal case, Judge Smith reiterated an earlier warning to again caution: “Highly consequential opinions should not be designated as unpublished in an obvious effort to discourage judges from voting in favor of en banc rehearing.” United States v. Ramirez, No. 22-50042 (Sept. 19, 2023).

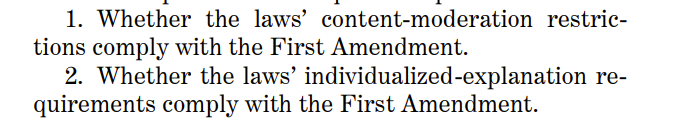

The Supreme Court has granted review of three social-media regulation cases, one of which is the 2022 2-1 panel opinion by the Fifth Circuit in Netchoice v. Paxton, which conflicts with a 2022 opinion from the Eleventh Circuit about similar subject matter. These are the two issues referenced in the Court’s order granting review:

I had an op-ed in today’s Dallas Morning News about recent friction between the Supreme Court and Fifth Circuit on standing in some high-profile constitutional/administrative-law cases.

A few years ago, I examined en banc opinons in the Dallas Court of Appeals, and concluded that they tended to be either: (1) “error correction” of panel opinions that had become out of step with the rest of the state and/or the supreme court; (2) “successful failure” cases where en banc review became moot when the supreme court took the case; and (3) “Goldilocks” cases that involve significant issues, but not of such importance that supreme-court review is guaranteed.

The Fifth Circuit’s en banc cases fit that general taxonomy (Brackeen and the FHFA case qualifying as “successful failures”), with the recent opinion in Hamilton v. Dallas County an example of error-correction. The majority opinion summarized:

[T]he panel concluded that it was “bound by this circuit’s precedent, which requires a Title VII plaintiff” to have “suffered some adverse employment action by the employer” and which says that “adverse employment actions include only ultimate employment decisions such as hiring, granting leave, discharging, promoting, or compensating.” Because “the denial of weekends off is not an ultimate employment decision,” the panel affirmed the district court’s dismissal. The panel concluded by urging the full court to “reexamine our ultimate-employment-decision requirement” in light of our deviation from Title VII’s plain text. We granted rehearing en banc to do so.

No. 21-10133 (Aug. 18, 2023) (en banc) (footnotes omitted).

After a well-publicized debacle in New York involving “research” in which ChatGPT invented nonexistent cases, the phenomenon of “hallucinatory” generative AI has arrived in Texas. The Waco Court of Appeals recently faulted a lawyer for providing a brief with three nonexistent cases (and, like the New York counsel, not responding when the problem was pointed out by the appellee). While there is nothing wrong with using ChatGPT to help with legal analysis and writing, uncritical acceptance of purported caselaw found “on the Internet” is always risky.

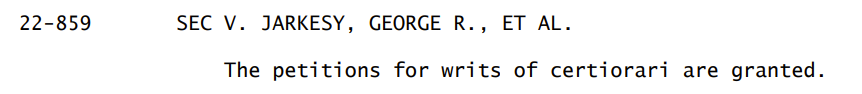

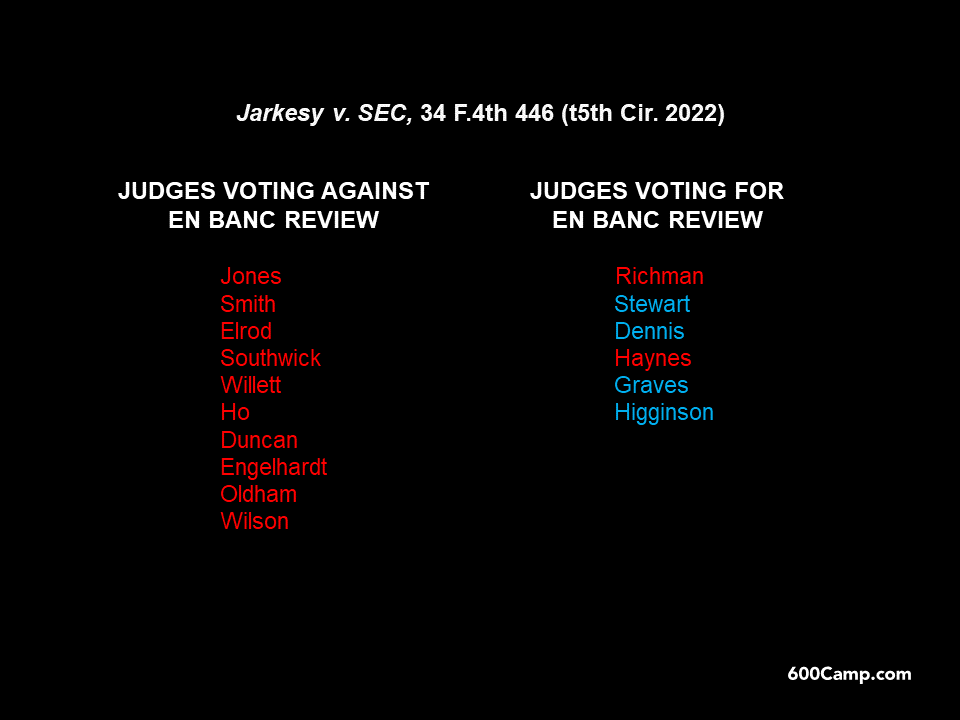

In May 2022, a Fifth Circuit panel held in Jarkesy v. SEC that the Seventh Amendment’s right to civil jury trial extends to an SEC enforcement action. The full Fifth Circuit later denied en banc review of the matter.

Critics of the administrative state celebrated the ruling as an important limit on agency power; others questioned whether “originalism” was fairly applied to an agency and a set of statutes that did not exist in 1792.

On June 30 of this year, the Supreme Court granted review of Jarkesy, which will be a fascinating addition to the next term of that court:

In United States v. Texas, last Friday, the Supreme Court reversed a Fifth Circuit judgment because Texas had no standing to bring a particular claim about immigration policy. The case echoes the proceedings in California v. Texas, a 2021 matter in which the Supreme Court also reversed a Fifth Circuit judgment for lack of standing — in that case, an issue about the enforceability of the Affordable Care Act.

In United States v. Texas, last Friday, the Supreme Court reversed a Fifth Circuit judgment because Texas had no standing to bring a particular claim about immigration policy. The case echoes the proceedings in California v. Texas, a 2021 matter in which the Supreme Court also reversed a Fifth Circuit judgment for lack of standing — in that case, an issue about the enforceability of the Affordable Care Act.

As Texas’s Attorney General, Greg Abbott famously quipped: “I go into the office in the morning. I sue Barack Obama, and then I go home.” In a recent interview, I suggest that these opinions are a yellow light for that approach to public-law litigation; Mark Stern makes a similar point in more colorful language for Slate. Time will tell whether that traffic signal is heeded.

Two New York lawyers filed a brief with “fake law” in it, having accepted at face value a “hallucination” by ChatGPT abouot several cases that did not in fact exist. The district court has now sanctioned them. The opinion is of broad general interest, given the great influence of generative AI in its few short months of widespread public availability. And it’s also of broad general interest in avoiding sanctions–the lawyers had at least one good chance, and maybe even two, of coming clean about their error, but instead “doubled down” with purported screenshots of the nonexistent cases.

Together with the able Raffi Melkonian from Houston, I presented the “Fifth Circuit Update” at the University of Texas appellate course last week; here is a copy of our PowerPoint.

Raskin v. Dallas ISD addresses whether a mother can sue, pro se, in federal court on behalf of her children under the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act. Acknowledging both the practical reality that many such actions must be brought pro se, and that the federal courts ordinarily require the professionalism of trained counsel, the majority opinion deftly read the relevant statutes to let the district court apply discretion to this issue on remand.

Raskin v. Dallas ISD addresses whether a mother can sue, pro se, in federal court on behalf of her children under the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act. Acknowledging both the practical reality that many such actions must be brought pro se, and that the federal courts ordinarily require the professionalism of trained counsel, the majority opinion deftly read the relevant statutes to let the district court apply discretion to this issue on remand.

A dissent favored an absolute rule allowing such pro se proceedings, noting, inter alia, customs about pro se representation when the Judiciary Act was adopted in 1789. (to be fair, though, women such as Ms. Raskin did not have the ability to sue about much of anything in 1789, pro se or otherwise).

A recent Texas Lawbook article considers a new standing order by Hon. Brantley Starr about reliance on language-model AI programs when writing briefs. Judge Starr’s point is well-taken and Rule 11 should probably be revised to include a specific reference to this issue, given how pervasive these programs will likely become in the near future.

I asked ChatGPT what it thought about the matter (specifically: “What are the pros and cons of requiring attorneys to certify to the accuracy of court fiings made with the assistance of language-model AI programs, such as yourself?”) and here is what it had to say:

______

Introducing a requirement for attorneys to certify the accuracy of court filings made with the assistance of AI language models like GPT-4 could have several pros and cons. Here are some:

Pros:

- Responsibility and Accountability: Requiring certification ensures that attorneys review the generated content thoroughly before submitting it, increasing the reliability and accuracy of the information presented. It also maintains responsibility with the attorney, discourishing the misuse of AI and ensuring ethical conduct.

- Increased Accuracy: By requiring attorneys to certify accuracy, any incorrect or misleading information generated by AI can be corrected, minimizing the risk of procedural or factual errors that could potentially affect a case’s outcome.

- Improved Understanding: Since an attorney must certify the accuracy of the filing, they’re incentivized to understand the nuances of the AI-generated content better, making sure they can defend it in court.

Cons:

- Additional Burden: This requirement could add to the workload of attorneys, who are already often busy. While AI systems can increase efficiency, the certification process may negate some of this advantage.

- Potential Liability Issues: There might be concerns about the increased legal liability for attorneys. If an error from an AI system slips through, the attorney could be held responsible, which could lead to professional consequences or disciplinary actions.

- Complexity of AI Outputs: AI language models can generate vast amounts of complex content. While they can be extremely useful, it might be challenging for attorneys to verify all details accurately, especially given the complexity of the legal language and the high stakes involved.

- Possible Overreliance: There is a risk that attorneys might rely too heavily on AI-generated content and miss important aspects of a case that the AI, which lacks a deep understanding or context, may not catch. While certification could theoretically mitigate this, the added responsibility may be insufficient.

Ultimately, the success of such a certification requirement will depend on the balance between leveraging the benefits of AI assistance and ensuring the maintained quality, accuracy, and ethical use of legal filings. As AI evolves, it’s crucial to continually reassess such policies to ensure they meet the needs and challenges of the legal profession.

Literature is filled with nonexistent books, such as the “Necronomicon” in the works of H.P. Lovecraft, the “Treatise on the Binomial Theorem” written by Sherlock Holmes’s menace, Professor James Moriarty, etc.

Literature is filled with nonexistent books, such as the “Necronomicon” in the works of H.P. Lovecraft, the “Treatise on the Binomial Theorem” written by Sherlock Holmes’s menace, Professor James Moriarty, etc.

To that collection, we can now add Varghese v. China South Airlines, Ltd., 925 F.3d 1339 (11th Cir. 2019).

ChatGPT helpfully offered that opinion to a New York lawyer researching a technical limitations issue. Unfortunately for that lawyer, the opinion did not actually exist and neither did any of the cases that it purported to cite. An understandably vexed federal judge is now considering sanctions about the matter.

Language-model AI tools are extraordinarily powerful and making advances every day. But they aren’t designed to do legal research, and anything they say about a specific precedent needs to be verified (and not by asking ChatGPT to verify itself, as happened in the federal case cited above).

In response to an April 27 letter from Senator Charles Schumer expressing concern about case-assignment practices in the Northern District of Texas (which, while well-intentioned, also notably misspells “Abilene” as “Abeline”), Chief Judge David Godbey wrote back yesterday to defend the District’s practices: “In addition to the fair administration of justice, we must also consider: the number and type of civil and criminal cases filed in a division, which varies significantly from division to division; the convenience of the jurors, witnesses, parties, and attorneys; the desire of communities to have local judges; the burden of travel on court personnel; and the need to provide judicial support for divisions without a resident district judge.”

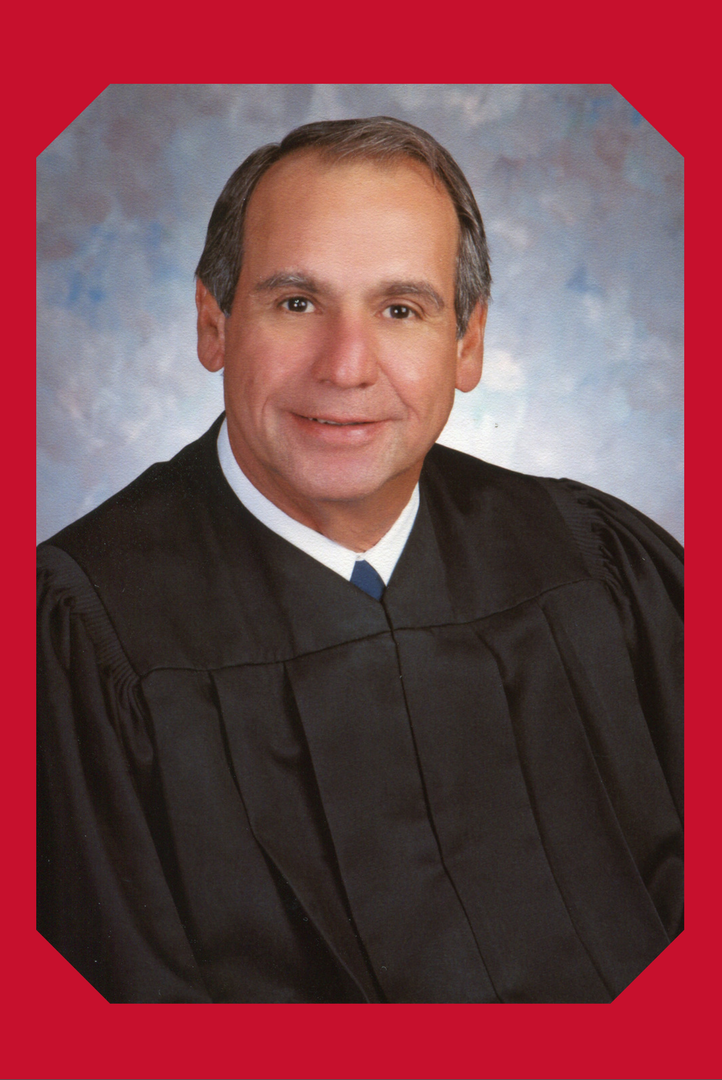

A judge at every level of the Texas state system, as well as the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, Hon. Fortunato “Pete” Benavides recently passed away. His life of dedicated public service is well described in this obituary.

A judge at every level of the Texas state system, as well as the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, Hon. Fortunato “Pete” Benavides recently passed away. His life of dedicated public service is well described in this obituary.

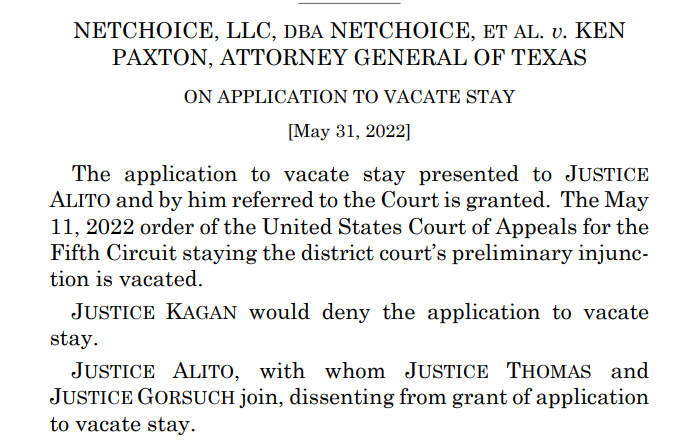

After the Supreme Court’s stay ruling yesterday, a Fifth Circuit panel will proceed wth oral argument on May 17 in New Orleans. (Information about the audio livestream may be found in that link.)

After the Supreme Court’s stay ruling yesterday, a Fifth Circuit panel will proceed wth oral argument on May 17 in New Orleans. (Information about the audio livestream may be found in that link.)

While the Supreme Court’s order said very little, the votes of seven Justices were consistent with the position of Judge Haynes when the stay issue was before the Fifth Circuit, and no Justice indicated agreement with the analysis of the per curiam panel majority. (I recently observed in Slate that the “Dobbs-era Supreme Court is well aware of the judicial strand of conservative thought, as well as the political.”).

President Biden has nominated Hon. Irma Ramirez, a long-serving magistrate judge from the Dallas area, for the vacant seat on the Fifth Circuit created by the resignation of Gregg Costa. More detail is in the coverage by the Dallas Morning News.

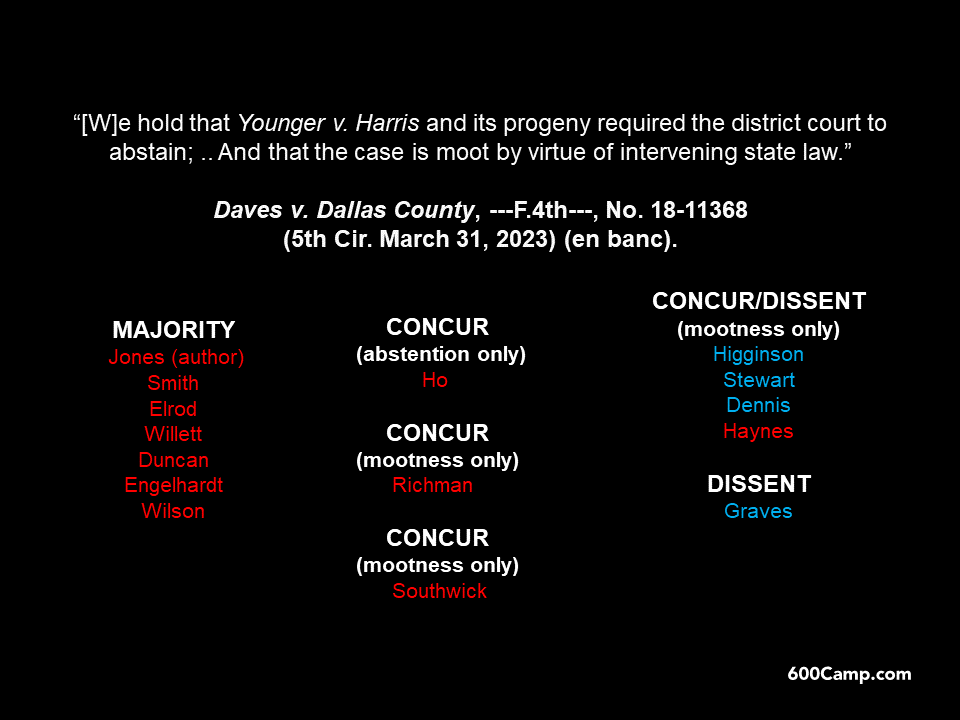

Longrunning litigation about pretrial bail in Texas criminal cases came to an end with a second en banc opinion, Daves v. Dallas County, No. 18-11368 (March 31, 2023). It held by a substantial majority that legislative changes to the relevant laws had mooted the case, and (8-7) that Younger abstention should have barred the case from proceeding in federal court in the first instance. The breakdown of votes and opinions is as follows:

In a dissent from a dismissal order in Chapman v. Doe, Justice Jackson questioned whether the Supreme Court had become too quick to vacate judgments, noting, inter alia, that “our common-law system assumes that judicial decisions are valuable and should not be cast aside lightly, especially because judicial precedents ‘are not merely the property of private litigants,’ but also belong to the public and ‘legal community as a whole.'” (reviewing United States v. Munsingwear, Inc., 340 U.S. 36 (1950)).

As she was the sole dissenter on this point, her views are apparently not shared by a majority of that court, but her analysis is still thought-provoking and deserves study, as it examines a part of the appellate process that often goes largely unnoticed. Thanks to Ben Taylor for drawing my attention to this one!

Last year the Fifth Circuit held that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau was funded through an unconstitutional mechanism that circumvented the Congressional appropriations process. That matter is now before the Supreme Court. The Second Circuit has now joined the fray in CFPB v. Law Offices of Crystal Moroney, P.C., No. 20-3471 (March 23, 2023), joining the D.C. Circuit in finding that the CFPB’s funding mechanism does not violated the Appropriations Clause.

The Fifth Circuit didn’t bite on a last-minute attempt to stop a trial in the Allen Stanford litigation, denying a mandamus petition (with memorable language obviously written by Judge Higginbotham despite the “per curiam” designation):

The Fifth Circuit didn’t bite on a last-minute attempt to stop a trial in the Allen Stanford litigation, denying a mandamus petition (with memorable language obviously written by Judge Higginbotham despite the “per curiam” designation):

This case is, at minimum, complex, featuring myriad fact-specific issues litigated over the course of nearly a decade and a half through multiple courts. Halting the litigation’s momentum mere days before trial is set to begin would require indisputable clarity as to its necessity. Here, no such need is evident; assisted by able briefing and a review of the record, we are unpersuaded that either petition reaches the high demands of mandamus, or that the movant has satisfied the similar burden of staying the trial….

The four most powerful words from the lips of a United States District Judge are simply “Call your first witness,” and the veteran presiding judge will so state in a few short days.

In re Toronto-Dominion Bank, No. 22-20648 (Feb. 14, 2023). (It could be debated whether those are in fact a trial judge’s most powerful words–a case could be made for “So ordered” or “Your objection is overruled,” for example.)

Last week’s opinion in United States v. Rahimi found that a federal law, criminalizing the possession of a firearm by someone under a domestic-violence restraining order, violated the Second Amendment’s protection of a right to bear arms.

The Attorney General plans to seek review. The perspective of a Dallas-based operator of a women’s shelter appears in this Fox 4 news story on the case. I recently wrote an op-ed about the opinion in the Dallas Morning News. A flavor of the national commentary about the case can be obtained from these representative articles in Slate and Reason.

On January 29, the Washington Post published a lengthy article about issues of the day in the Fifth Circuit.

Significantly different and tone and focus, it is similar in scope to a Texas Monthly article of last summer about the Court.

Last July, I fearlessly predicted that “[a] petition for en banc rehearing seems a near certainty” in Wages & White Lion Investments v. FDA, a challenge to a significant FDA regulation in the vaping industry. The full court has now voted to consider the matter en banc; time will tell if the panel majority’s analysis goes up in smoke, or whether the case simply offers smoke and no fire.

Last July, I fearlessly predicted that “[a] petition for en banc rehearing seems a near certainty” in Wages & White Lion Investments v. FDA, a challenge to a significant FDA regulation in the vaping industry. The full court has now voted to consider the matter en banc; time will tell if the panel majority’s analysis goes up in smoke, or whether the case simply offers smoke and no fire.

The Senate today confirmed Hon. Dana Douglas of Louisiana as the newest judge on the Fifth Circuit, taking a seat vacated by long-serving Hon. James Dennis. Welcome to the court, Judge Douglas! Louisiana’s Advocate has a thorough story about her confirmation hearings and personal background.

The Senate today confirmed Hon. Dana Douglas of Louisiana as the newest judge on the Fifth Circuit, taking a seat vacated by long-serving Hon. James Dennis. Welcome to the court, Judge Douglas! Louisiana’s Advocate has a thorough story about her confirmation hearings and personal background.

12-3 (one recusal), the full Fifth Circuit denied en banc review in Freedom From Religion Foundation v. Mack, in which the panel found no coercion (and thus no standing) in a challenge to a Texas JP’s pre-court practices.

With #RIPTwitter trending as the top hashtag on that platform, it seemed like a good time to reflect on the phenomenon that is/was #appellatetwitter, and recall the remarkable talent of now-Judge @JusticeWillett for legal tweeting:

With #RIPTwitter trending as the top hashtag on that platform, it seemed like a good time to reflect on the phenomenon that is/was #appellatetwitter, and recall the remarkable talent of now-Judge @JusticeWillett for legal tweeting:

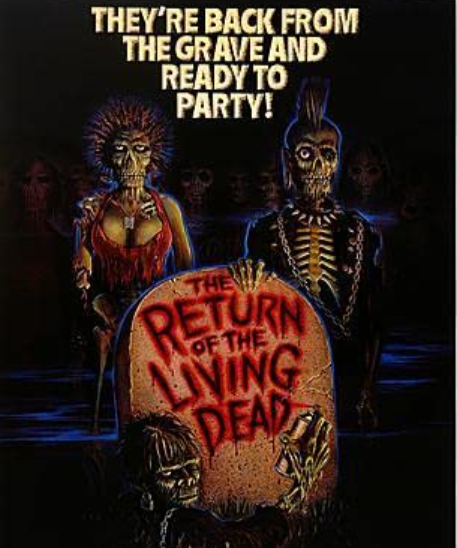

In the 1985 classic, “Return of the Living Dead,” a rainstorm spreads a zombie-creating chemical throughout a city. In 2022, the Supreme Court’s relentless focus on originalism in cases like Dobbs has also awakened long-dead legal doctrines (even as it put to bed the prospects for a “Red Wave” in 2022’s Congressional elections).

In the 1985 classic, “Return of the Living Dead,” a rainstorm spreads a zombie-creating chemical throughout a city. In 2022, the Supreme Court’s relentless focus on originalism in cases like Dobbs has also awakened long-dead legal doctrines (even as it put to bed the prospects for a “Red Wave” in 2022’s Congressional elections).

Such a resurrection can be seen in the concurrence from Golden Glow Tanning Salon v. City of Columbus, No. 21-60898 (Nov. 8, 2022), which advocates an examination of a “right to earn a living” in light of how such economic matters were understood in the late 1700s.

Of course, that phrasing is precisely how the Supreme Court described the issue in Lochner v. New York, the long-discredited 1905 opinion that struck down a maximum-hour restriction in the baking industry:

“Statutes of the nature of that under review, limiting the

hours in which grown and intelligent men may labor to earn their living, are mere meddlesome interferences with the rights of the individual ….”

The Supreme Court abandoned Lochner in the 1930s when laissez-faire ideas proved useless in the face of a systemic failure of capitalism itself. There is, of course, ample room for argument about the proper role of government in the economy. But the invocation of “originalism” to simply ignore Lochner ‘s failure is not consistent with the recognized best practices for battling zombies.

The slippery statutory-interpretation question in United States v. Palomares, briefly summarized in Monday’s post, presented a concurrence by Judge Andy Oldham. In it, he reminded of the importance of “textualism” in statutory interpretation, while cautioning against “hyper-literalism”:

The slippery statutory-interpretation question in United States v. Palomares, briefly summarized in Monday’s post, presented a concurrence by Judge Andy Oldham. In it, he reminded of the importance of “textualism” in statutory interpretation, while cautioning against “hyper-literalism”:

“‘[W]ords are given meaning by their context, and context includes the purpose of the text.’ As Justice Scalia once quipped, without context, we could not tell whether the word draft meant a bank note or a breeze. Such nuance is lost on the hyper-literalist.”

(citations omitted). He further observed:

“[H]yper-literalism … opens textualism to the very criticism that necessitated textualism in the first place. In one of the most influential law review articles ever written, Karl Llewellyn denigrated the late nineteenth century ‘Formal Period,’ in which ‘statutes tended to be limited or even eviscerated by wooden and literal reading, in a sort of long-drawn battle between a balky, stiff-necked, wrongheaded court and a legislature which had only words with which to drive that court.'”

(emphasis added, quoting Karl M. Llewellyn, “Remarks on the Theory of Appellate Decision and the Rules or Canons about How Statutes Are to Be Construed,” 3 Vanderbilt L. Rev. 395 (1950)).

The prefix “hyper-” is well chosen; Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulations developed the concept of “hyperreality,” by which “simulacra” of reality can supplant reality itself–precisely the scenario described by Llewellyn and Judge Oldham’s concurrence:

The prefix “hyper-” is well chosen; Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulations developed the concept of “hyperreality,” by which “simulacra” of reality can supplant reality itself–precisely the scenario described by Llewellyn and Judge Oldham’s concurrence:

If we were able to take as the finest allegory of simulation the Borges tale where the cartographers of the Empire draw up a map so detailed that it ends up exactly covering the territory (but where, with the decline of the Empire this map becomes frayed and finally ruined, a few shreds still discernible in the deserts – the metaphysical beauty of this ruined abstraction, bearing witness to an imperial pride and rotting like a carcass, returning to the substance of the soil, rather as an aging double ends up being confused with the real thing), this fable would then have come full circle for us, and now has nothing but the discrete charm of second-order simulacra.

Bloomberg Law provides a good summary of yesterday’s arguments in SEC v. Cochran, addressed by the en banc Fifth Circuit in 2021, as to the appropriate places to advance constitutional challenges to SEC enforcement actions.

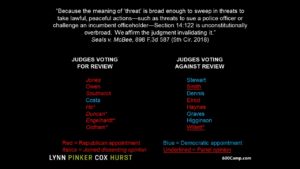

The Fifth Circuit recently declined to review Jarkesy v. SEC en banc; the division of votes was as follows (names in blue were appointed by a Democratic president; red, by a Republican one):

The recent Crane v. City of Arlington opinion declined to dismiss a traffic-stop case on qualified immunity grounds, noting significant factual dispute about how the situation escalated into a tragic shooting. No. 21-10644 (revised Oct. 4, 2022). The Dallas Morning News covered the case, and I did a lengthy interview with Fox 4 in Dallas about it.

Professor Steve Vladeck recently filed a provocative amicus brief about the State of Texas’s forum-selection practices in public law / constitutional cases.

The Fifth Circuit is soliciting comment on a potential change to local rule 47.5.4:

Legal instruments often contain polite phrases before they get to the actual command in the instrument (“you have been sued and must file an answer,” or “you have been drafted,” etc.) Defense Distributed v. Platkin presents an unusual example of polite language in a legal instrument with no accompanying command, the background for which is as follows:

- Earlier this year, a 2-1 Fifth panel decision ordered a district judge, who had transferred a case about 3-D printed firearms to the District of New Jersey, to request the retransfer of that case back to Texas. (Judge Jones wrote the opinion, joined by Judge Elrod, with Judge Higginson dissenting).

- The New Jersey court considered the matter and declined the request on July 27.

- The Texas judge then closed the file, prompting further proceedings in the Fifth Circuit.

On September 16, the Court issued a routine order setting the matter for the earliest available argument date–but with a concurrence joined by two judges, asking that the New Jersey court reconsider the issue of transfer back to Texas:

“We can think of no substantive reason—and none has been offered to us—why this case should nevertheless proceed in New Jersey rather than Texas, other than disagreement with our decision in Defense Distributed. The Attorney General of New Jersey confirmed as much during oral argument. So we respectfully ask the District of New Jersey to honor our decision in Defense Distributed and grant the request to return the case back to the Western District of Texas—consistent with the judiciary’s longstanding tradition of comity, both within and across the circuits ….”

No. 22-50669 (Sept. 16, 2022) (Judge Ho concurring, joined by Judge Elrod, but not Judge Graves).

Sambrano v. United Airlines, a religious-discrimination case about an airline’s vaccine mandate that prompted a (literally) fiery dissent from the panel opinion, ended in a 13-4 vote against en banc review. A dissent again urged caution in the use of unpublished (and thus, nonprecedential) opinions in significant matters. No. 21-11159 (Aug. 18, 2022).

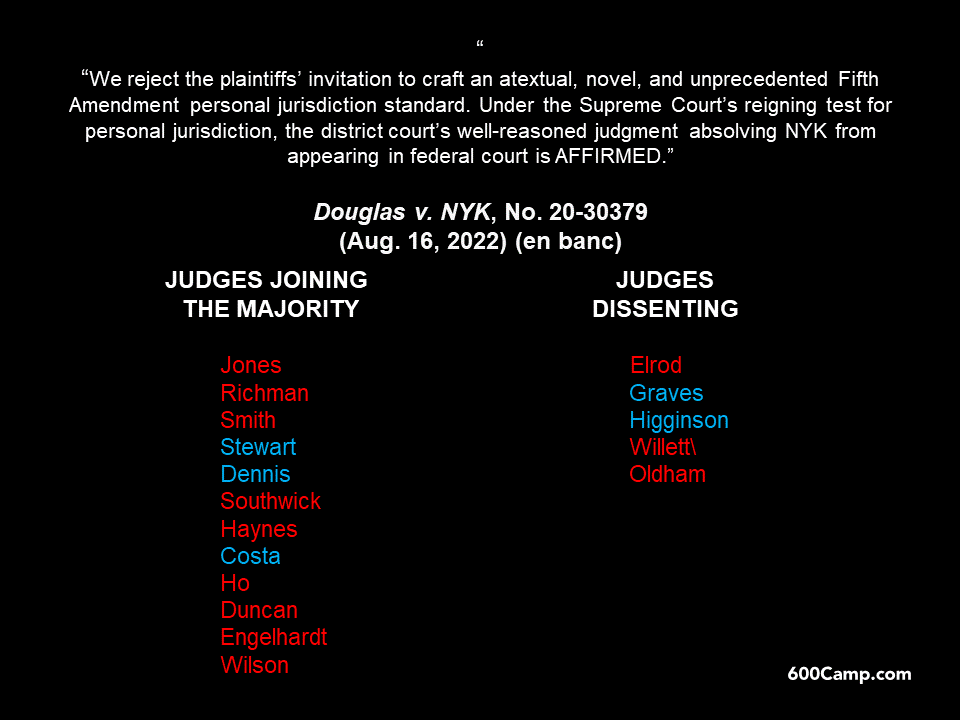

The 2017 collision between the MV ACX Crystal and the destroyer U.S. Fitzgerald led to litigation in New Orleans federal court against NYK, a huge shipping concern with global operations. The district court acknowledged that for this international case, the constitutional standard for personal jurisdiction was based on the Fifth rather than the Fourteenth Amendment, but concluded that the standards were materially similar and that it lacked jurisdiction over NYK.

A Fifth Circuit panel affirmed and the en banc court did also, noting that the other Circuits addressing this constitutional question reached similar conclusions. A dissent argued that the majority’s position about jurisdiction would undermine the effective operation of Congressionally-created causes of action involving asset seizure by the Castro regime and terrorist activity. Douglass v. NYK, No. 20-30382 (Aug. 16, 2022) (en banc). The judges’ votes broke along atypical lines and are detailed below:

The well-known poem Antigonish begins:

Yesterday, upon the stair,

I met a man who wasn’t there

He wasn’t there again today

I wish, I wish he’d go away.

In that general spirit, in recent days, both the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and the Court of Appeals for the Fifth District at Dallas had close en banc votes involving questions of arbitrability, as to a party who “wasn’t there”–who had not signed an arbitration agreement, but was nevertheless potentially subject to it. (The Dallas case is discussed here; the Fifth Circuit’s, here.)

Whether the timing is an example of synchronicity I will leave to others. The courts’ difficulty with these issues shows the strong feelings provoked by the issue of court access, even among very sophisticated jurists, in an area of the law with well-developed case law on many key points.

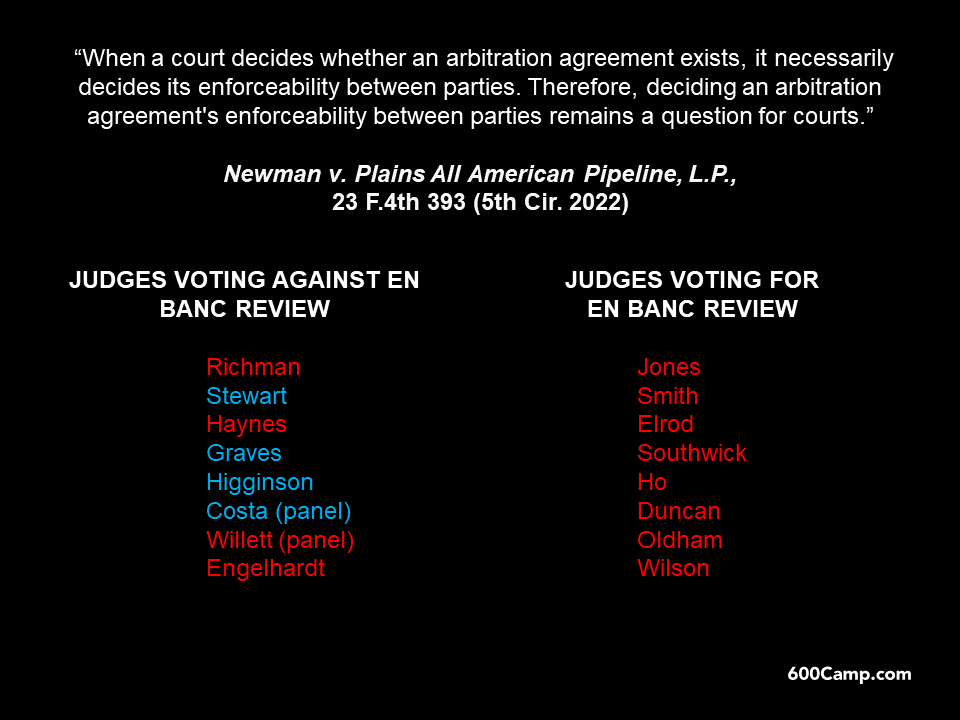

By an 8-8 vote over a dissent, the full Fifth Circuit declined to review Newman v. Plains All Am. Pipeline, L.P., a case about a court’s power to determine arbitrability when a nonsignatory seeks to enforce an arbitration clause. The breakdown of votes was as follows (Senior Judge King was the third panel member):

By an 8-8 vote over a dissent, the full Fifth Circuit declined to review Newman v. Plains All Am. Pipeline, L.P., a case about a court’s power to determine arbitrability when a nonsignatory seeks to enforce an arbitration clause. The breakdown of votes was as follows (Senior Judge King was the third panel member):

Beatriz Ball, L.L.C. v. Barballago Co., No. 21-30029 (July 12, 2022), a trade-dress case under the Lanham Act, produced a thorough concurrence by soon-to-depart Judge Costa about the distinctions between review of bench trials, and review of jury verdicts. He began by observing:

Beatriz Ball, L.L.C. v. Barballago Co., No. 21-30029 (July 12, 2022), a trade-dress case under the Lanham Act, produced a thorough concurrence by soon-to-depart Judge Costa about the distinctions between review of bench trials, and review of jury verdicts. He began by observing:

“I write separately to remark on how our remand of the trade dress claim reveals a paradox that has perplexed me about bench trials: We give a trial judge’s detailed and intensive factfinding less deference than a jury’s unexplained verdict.

If a jury had rejected Beatriz Ball’s trade dress claim—giving no more explanation than a simple ‘No’ on the verdict form—we would presumably affirm. After all, we do not hold that Beatriz Ball is entitled to judgment as a matter of law on this claim. Instead, we remand for the district court to reassess the trade dress claim because of some errors in its 33 pages explaining why it found no protectable trade dress.”

And he concluded after a review of history and social-science research: “It turns out, then, that there is good reason for the seeming anomaly of giving less deference to bench trials: Larger and more representative groups are the ones more likely to reach the correct outcome.”

In its analysis, the concurrence notes one commentator’s observation that “while the Seventh Amendment does not compel the backwards-seeming rule giving less deference to judges’ findings, it does explain it. ‘[O]ur traditional and constitutionalized reverence for jury trial’ is why we trust juries more.” An element of that “traditional reverence” may well include some indifference to whether a jury in fact reaches a “correct” result, as the mere existence of a jury has a powerful symbolic value in its own right. See generally Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 90 (1986) (“In view of the heterogeneous population of our Nation, public respect for our criminal justice system and the rule of law will be strengthened if we ensure that no citizen is disqualified from jury service because of his race.”).

In its analysis, the concurrence notes one commentator’s observation that “while the Seventh Amendment does not compel the backwards-seeming rule giving less deference to judges’ findings, it does explain it. ‘[O]ur traditional and constitutionalized reverence for jury trial’ is why we trust juries more.” An element of that “traditional reverence” may well include some indifference to whether a jury in fact reaches a “correct” result, as the mere existence of a jury has a powerful symbolic value in its own right. See generally Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 90 (1986) (“In view of the heterogeneous population of our Nation, public respect for our criminal justice system and the rule of law will be strengthened if we ensure that no citizen is disqualified from jury service because of his race.”).

“[T]he oldest and most consistent thread in the federal law of justiciability is that the federal courts will not give advisory opinions.” E.g., In re: Franchise Servcs. of N. Am., 891 F.3d 198 (5th Cir. 2018). That said, not all statements of legal rules are the same (as detailed in this Pepperdine Law Review article that I co-authored several years ago). Illustrating that point:

- In Leonard v. Martin, the panel majority in a discovery-order mandamus observed in a footnote: “In mandamus cases, this court often holds ‘that a district court erred, despite stopping short of issuing a writ of mandamus.'” (citation omitted) No. 21-30475 (June 30, 2022).

- In SEC v. Novinger, the concurrence in a case resolved on procedural grounds about Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b) observed: “If you want to settle, SEC’s policy says, ‘Hold your tongue, and don’t say anything truthful—ever’—or get bankrupted by having to continue litigating with the SEC. A more effective prior restraint is hard to imagine. … Given the agency’s current activism, I think it will not be long before the courts are called on to fully consider this policy.” No. 21-10985 (July 12, 2022).

- And in SEC v. Hallam, a case about the kind of disgorgement available as a remedy under the securities laws, the Court observed: “… if we are confronted with an appeal from a request for an award of that nature, we may need to decide whether it could be equitable disgorgement consistent with Liu’s constraining those awards to ‘net profits[.]” And that may also require us to resolve Hallam’s contention that the SEC is required strictly to trace the ill-gotten gains, and the profits on them, into assets still held by the defendant.” No. 21-10222 (July 19, 2022) (citations omitted).

My friend Walter Woodruff and I have picked our “Top Five Cases to Know” from the Fifth Circuit for the first half of 2022 – we agreed on 3/5 – the Bar Association for the Fifth Federal Circuit has been Tweeting them out the last few days!

A recent Texas Monthly article offers a detailed analysis of the Fifth Circuit and its recent opinions.

The Fifth Circuit has set for rehearing en banc:

- Feds for Medical Freedom v. Biden (the “federal employee vaccine” case, in which a panel reversed an injunction against a Presidential executive order about COVID-19 vaccination); and

- Cargill v. Garland (the “bump stock” case, in which a panel rejected a challenge to ATF’s regulation that treats a bump stock as a “machine gun” under the relevant firearms statute)

Ardoin v. Robinson, in which the Fifth Circuit denied a stay in a case about a new Louisiana congressional district, was stayed by the Supreme Court, which also granted the cert petition and held the matter held in abeyance pending a ruling in another case.

In his 19th round of judicial nominations, announced yesterday, President Biden has nominated U.S. Magistrate Judge Dana Douglas of New Orleans to the Fifth Circuit. The White House website provides a short biographical sketch:

The Fifth Circuit recently put in place some new local rules about disclosure statements and certificates of service.

The unsuccessful parties in the NetChoice v. Paxton litigation have asked the Supreme Court, through Circuit Justice Alito, for an emergency stay. A response is due May 18.

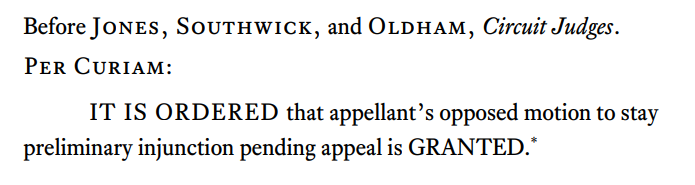

A Fifth Circuit motions panel granted Texas’ request to stay a preliminary injunction against that state’s law about content moderation by major social media platforms; commentators suggest that a rapid Supreme Court appeal will now occur. (The asterisk below indicates that the ruling was not unanimous. No opinion has issued yet; argument was just conducted on May 9th.)

Two new Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure have been finalized and transmitted to Congress, they clarify earlier rule 25 about privacy protection, and 42 about voluntary dismissal.

Johnson v. Huffington Post held, as to a libel claim, that Fifth Circuit precedent compelled dismissal for lack of personal jurisdiction: “HuffPost is interactive, but its story about Johnson has no ties to Texas. The story does not mention Texas. It recounts a meeting that took place outside Texas, and it used no Texan sources. Accordingly, we lack jurisdiction over HuffPost with respect to Johnson’s libel claim.” The full court recently voted 10-7 to not take the matter en banc, as follows:

The third panel member, Judge King, as a senior judge was not eligible to participate in the en banc vote. The four judges whose names are underlined joined a dissent from the denial of en banc review.

The third panel member, Judge King, as a senior judge was not eligible to participate in the en banc vote. The four judges whose names are underlined joined a dissent from the denial of en banc review.

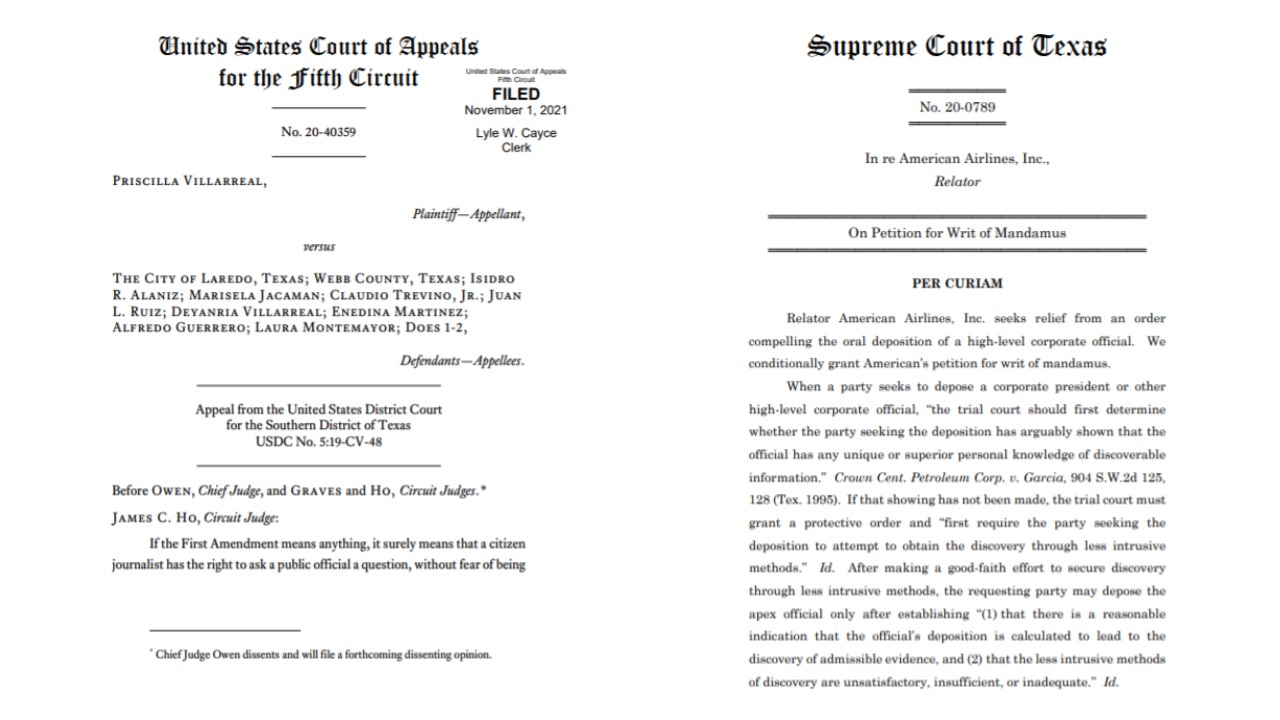

Reversing the Fifth Circuit’s opinion in City of Austin v. Reagan Nat’l Advertising, 972 F.3d 696 (5th Cir. 2020), the Supreme Court held that Austin’s use of an “on-/off-premises distinction” did not create a content restriction. The majority opinion reasoned:

Reversing the Fifth Circuit’s opinion in City of Austin v. Reagan Nat’l Advertising, 972 F.3d 696 (5th Cir. 2020), the Supreme Court held that Austin’s use of an “on-/off-premises distinction” did not create a content restriction. The majority opinion reasoned:

A sign’s substantive message itself is irrelevant to the application of the provisions; there are no content-discriminatory classifications for political messages, ideological messages, or directional messages concerning specific events, including those sponsored by religious and nonprofit organizations. Rather, the City’s provisions distinguish based on location: A given sign is treated differently based solely on whether it is located on the same premises as the thing being discussed or not. The message on the sign matters only to the extent that it informs the sign’s relative location. The on-/off-premises distinction is therefore similar to ordinary time, place, or manner restrictions.

No. 20-1029 (U.S. April 21, 2022) (applying Reed v. Gilbert, 576 U.S. 155 (2015)).

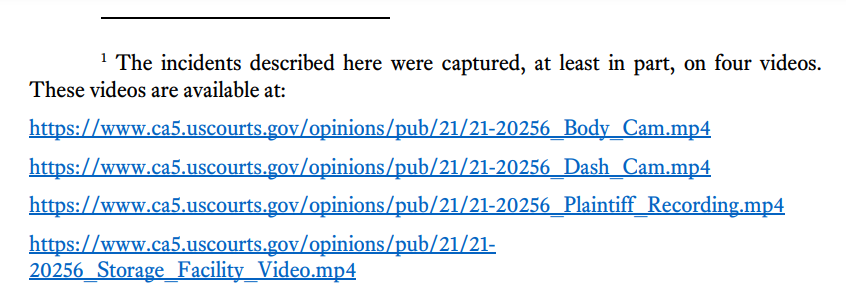

While Solis v. Serrett deftly summarizes the Baroque case law about qualified immunity and use of force, it will be remembered for its constructive use of hyperlinks — links to the relevant video footage about the incidents in question. Particularly in this area of law, where dash and body cameras often provide critical evidence, including this material in the opinion provides helpful guidance for law enforcement officers and their counsel. No. 21-20256 (April 21, 2022) (citing, inter alia, this body camera video and this dash camera video).

While Solis v. Serrett deftly summarizes the Baroque case law about qualified immunity and use of force, it will be remembered for its constructive use of hyperlinks — links to the relevant video footage about the incidents in question. Particularly in this area of law, where dash and body cameras often provide critical evidence, including this material in the opinion provides helpful guidance for law enforcement officers and their counsel. No. 21-20256 (April 21, 2022) (citing, inter alia, this body camera video and this dash camera video).

Of general interest to court-watchers, building on a recent interview that I did with the Lincoln Project, the current episode of the “Coale Mind” podcast examines why today’s Supreme Court is like a bowl of soup, heated by two separate burners.

The first is the ongoing scrutiny over Justice Thomas’s recusal decisions in matters related to his wife’s political activity. The second, cool now but with the potential to become blazing hot, is the pending Dobbs case in which the Court could significantly limit or even overrule Roe v. Wade.

The combined heat potentially generated by these two issues–an ethical dispute about a Justice coupled with the possibility of a uniquely controversial ruling–could present a legitimacy problem for the Court of a magnitude not seen in recent memory.

The panel majority opinion in Defense Distributed v. Bruck presents a rare — indeed, near-singular — grant of mandamus relief as to a transfer of venue (combined with a ruling about severance). The business at issue involves the growing, and controversial, field of creating firearms with 3-D printers. A dissent made a number of objections, substantive and procedural. No. 21-50327 (April 1, 2022).

The panel majority opinion in Defense Distributed v. Bruck presents a rare — indeed, near-singular — grant of mandamus relief as to a transfer of venue (combined with a ruling about severance). The business at issue involves the growing, and controversial, field of creating firearms with 3-D printers. A dissent made a number of objections, substantive and procedural. No. 21-50327 (April 1, 2022).

Trafigura Trading v. United States featured a dispute about one of the many prohibitions in Article I Section 9 of the Constitution; specifically, clause 5, which says: “No Tax or Duty shall be laid on Articles exported from any State.” An oil company argued that a federally-imposed charge on oil exports, collected to finance the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund, violated this provision.

The district court ruled for the oil company and a Fifth Circuit panel affirmed. One judge, drawing heavily from lyrics made famous by “Hamilton,” described the surprisingly colorful history of this provision, and voted to affirm. Another judge voted to affirm but declined to join that opinion. And the third judge dissented. As a result, the other opinion had no quorum supporting it and thus lacked precedential effect. No. 21-20127 (March 24, 2022).

The district court ruled for the oil company and a Fifth Circuit panel affirmed. One judge, drawing heavily from lyrics made famous by “Hamilton,” described the surprisingly colorful history of this provision, and voted to affirm. Another judge voted to affirm but declined to join that opinion. And the third judge dissented. As a result, the other opinion had no quorum supporting it and thus lacked precedential effect. No. 21-20127 (March 24, 2022).

On that broader subject, cf. Sambrano v. United Airlines, No. 21-11159 (Feb. 17, 2022) (Smith, J., dissenting) (sympathizing with “the hapless trial judge or conscientious advocate” that must reason from nonprecedential rulings); see generally Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 78 (May 28, 1788) (“To avoid an arbitrary discretion in the courts, it is indispensable that they should be bound down by strict rules and precedents, which serve to define and point out their duty in every particular case that comes before them; and it will readily be conceived from the variety of controversies which grow out of the folly and wickedness of mankind, that the records of those precedents must unavoidably swell to a very considerable bulk, and must demand long and laborious study to acquire a competent knowledge of them.”).

The Texas Lawbook summarizes the many practical pointers from an hour-long discussion among Judges Haynes, Costa, and Ho at the recent Bench-Bar conference of the Northern District of Texas. Judge Hendrix from that District’s Lubbock Division moderated.

The Texas Lawbook summarizes the many practical pointers from an hour-long discussion among Judges Haynes, Costa, and Ho at the recent Bench-Bar conference of the Northern District of Texas. Judge Hendrix from that District’s Lubbock Division moderated.

A fiery dissent (literally fiery, as it warns that “the Good Ship Fifth Circuit is afire”) in Sambrano v. United Airlines faults the majority for, among other matters, not publishing the opinion. No. 21-11159 (Feb. 17, 2022). The opinions’ review of Fifth Circuit Local Rule 47.5.4 echoes a long-running debate, throughout all appellate courts, about the benefits and detriments of having multiple tiers of judicial precedent.

A fiery dissent (literally fiery, as it warns that “the Good Ship Fifth Circuit is afire”) in Sambrano v. United Airlines faults the majority for, among other matters, not publishing the opinion. No. 21-11159 (Feb. 17, 2022). The opinions’ review of Fifth Circuit Local Rule 47.5.4 echoes a long-running debate, throughout all appellate courts, about the benefits and detriments of having multiple tiers of judicial precedent.

Texas practitioners will recall similar debate leading up to the adoption of Tex. R. App. P. 47.4, the “memorandum opinion” rule. They will also likely see similarities between this strongly worded dissent and the concurrence in Steward Health Care System v. Saidara from the Dallas Court of Appeals in 2021, which also examined the policy judgments embodied in a different set of appellate-procedure rules.

The Texas Lawbook reports that Judge Gregg Costa will resign his position on the Fifth Circuit this summer. Please check the Lawbook‘s page for further information.

A Louisiana-based defendant removed a class action brought by an individual citizen of Louisiana, contending that a co-defendant’s “non-diverse Louisiana citizenship could be disregarded because the [statutory] claims against [the co-defendant] were ‘improperly and egregiously misjoined’ with the assignment-based bad faith claim against the removing defendant.”

A Louisiana-based defendant removed a class action brought by an individual citizen of Louisiana, contending that a co-defendant’s “non-diverse Louisiana citizenship could be disregarded because the [statutory] claims against [the co-defendant] were ‘improperly and egregiously misjoined’ with the assignment-based bad faith claim against the removing defendant.”

This concept — called “fraudulent misjoinder” and reliant upon state-law procedural rules — is distinct from the traditional concept of “improper joinder” (a/k/a “fraudulent joinder”), which focuses on the viability of the claim against the nondiverse defendant.

The panel majority in Williams v. Homeland Ins. Co., written by Judge Haynes and joined by Judge Ho, soundly rejected removal based on fraudulent misjoinder, emphasizing the doctrine’s practical consequences: “Adopting the fraudulent misjoinder doctrine will dramatically expand federal jurisdiction, putting the federal district courts in this circuit in the position of resolving procedural matters that are more appropriately resolved in state court—all without a clear statutory hook.” No. 20-30196 (Nov. 30, 2021).

A concurrence by Judge Ho emphasized the importance of the statutory text in rejecting the doctrine; a dissent by Judge Jones focused on “the unusual circumstances here, which bespeak obvious joinder machinations undertaken to avoid federal court.” (both opinions are in the above link). The trio of opinions suggests that this case may receive serious consideration for en banc review.

I recently wrote an article, “Federalism and Appellate Procedure: Five Texas-Federal Differences to Know,” in the Appellate Advocate, the quarterly publication by the Appellate Section of the State Bar of Texas. I hope you find it interesting and useful.

The fantastically controversial Texas abortion statute returned to the Fifth Circuit, which granted an administrative stay on Friday, October 8, while it receives further briefing about a stay during the appeal of Judge Pittman’s preliminary-injunction order. Enthusiasts of court history will note that the motions panel —

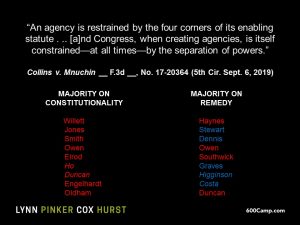

bears substantial similarity to the original panel in what led to the 2021 Supreme Court opinion in Collins v. Yellen. The panel divided 2-1 (Judges Haynes and Stewart, joining) about the constitutional problem with Fannie Mae’s regulator, and then again divided 2-1 (Judges Haynes and Willett, joining) about the proper remedy:

bears substantial similarity to the original panel in what led to the 2021 Supreme Court opinion in Collins v. Yellen. The panel divided 2-1 (Judges Haynes and Stewart, joining) about the constitutional problem with Fannie Mae’s regulator, and then again divided 2-1 (Judges Haynes and Willett, joining) about the proper remedy:

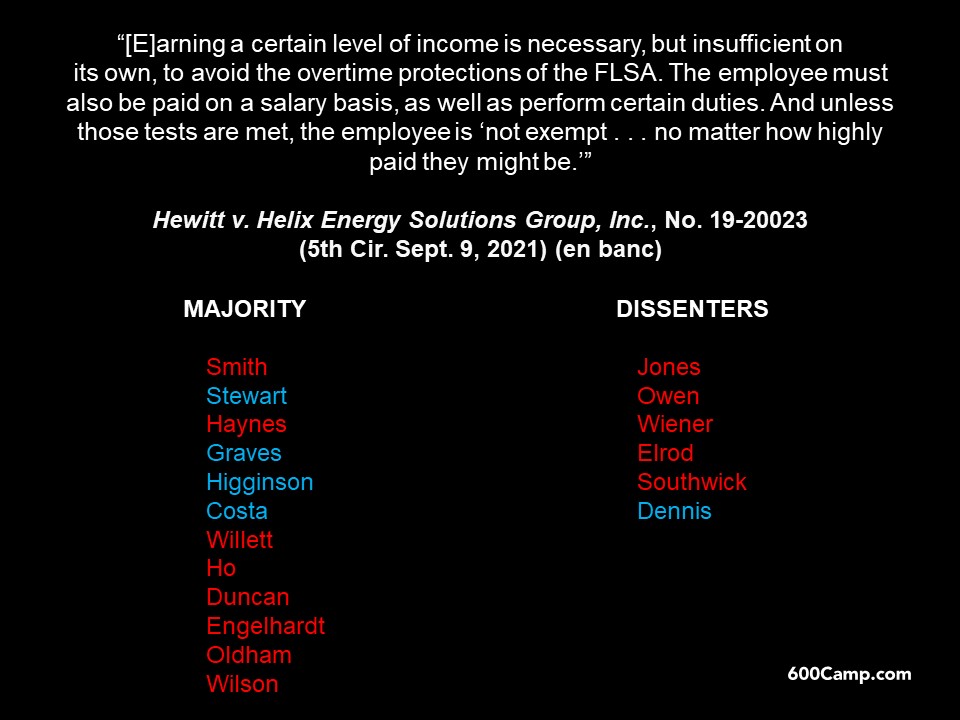

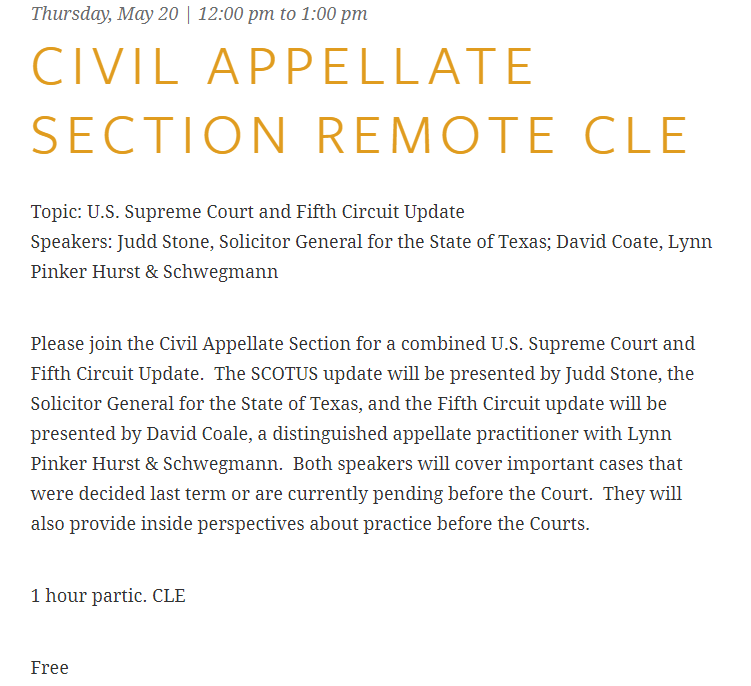

The en banc court divided along atypical lines in Hewitt v. Helix Energy, a dispute about overtime-pay obligations for highly compensated employees in the oil-and-gas industry. The Texas Lawbook and Houston Chronicle have covered the opinion thoroughly; below is a chart showing which judges joined the majority opinion and which judges dissented in some way. Note that Senior Judge Wiener participated in this en banc case because he was part of the original panel.

Longtime observers of the Court may see echoes of the divided en banc court in Mississippi Poultry Ass’n v. Madigan, 31 F.3d 293 (5th Cir. 1994) (en banc), a dispute about the import of the word “same” in the Poultry Products Inspection Act.

Counsel failed to file a summary-judgment response because his notification of filing went to his email “spam” folder. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the denial of relief under Fed. R. Civ. P. 59(e):

Counsel failed to file a summary-judgment response because his notification of filing went to his email “spam” folder. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the denial of relief under Fed. R. Civ. P. 59(e):

“It is not ‘manifest error to deny relief when failure to file was within [Rollins’s] counsel’s ‘reasonable control.’ Notice of Home Depot’s motion for summary judgment was sent to the email address that Rollins’s counsel provided. Rule 5(b)(2)(E) provides for service ‘by filing [the pleading] with the court’s electronic-filing system’ and explains that ‘service is complete upon filing or sending.’ That rule was satisfied here. Rollins’s counsel was plainly in the best position to ensure that his own email was working properly—certainly more so than either the district court or Home Depot. Moreover, Rollins’s counsel could have checked the docket after the agreed deadline for dispositive motions had already passed.”

Rollins v. Home Depot USA, No. 20-50736 (Aug. 9, 2021).

The Supreme Court will review Reagan National Advertising v. City of Austin, 972 F.3d 696 (5th Cir. 2020). The court’s summary of the issue presented is below, and here is my discussion of the case on the Coale Mind podcast —