Applying Singh v. RadioShack Corp., 882 F.3d 137 (5th Cir. 2018), which in turn relied upon Fifth Third Bancorp v. Dudenhoeffer, 134 S. Ct. 2459 (2014), the Fifth Circuit rejected a duty-of-prudence claim against an ERISA fiduciary based on the defendants allowing investments to continue a troubled company’s stock. Specifically, the plaintiffs alleged that the defendants “knew that it was inappropriate to rely on the market price of Idearc stock because their own fraudulent activities had caused the public markets to overvalue Idearc stock.” The Court did not agree: “[T]he alleged fraud is by definition not public information, and [Plaintiff] does not address how this information would affect the reliability of the market price ‘as an unbiased assessment of the security’s value in light of all public information.'” No. 16-11590 (June 27, 2018).

Applying Singh v. RadioShack Corp., 882 F.3d 137 (5th Cir. 2018), which in turn relied upon Fifth Third Bancorp v. Dudenhoeffer, 134 S. Ct. 2459 (2014), the Fifth Circuit rejected a duty-of-prudence claim against an ERISA fiduciary based on the defendants allowing investments to continue a troubled company’s stock. Specifically, the plaintiffs alleged that the defendants “knew that it was inappropriate to rely on the market price of Idearc stock because their own fraudulent activities had caused the public markets to overvalue Idearc stock.” The Court did not agree: “[T]he alleged fraud is by definition not public information, and [Plaintiff] does not address how this information would affect the reliability of the market price ‘as an unbiased assessment of the security’s value in light of all public information.'” No. 16-11590 (June 27, 2018).

Courtesy of the Huffington Post, here are seven good trivia questions about the Declaration of Independence to enjoy on your July 4 holiday.

Courtesy of the Huffington Post, here are seven good trivia questions about the Declaration of Independence to enjoy on your July 4 holiday.

The judgment creditor in Century Surety Co. v. Seidel, a case involving sexual assault on an underage restaurant employee, tried valiantly to collect from the restaurant’s insurance carrier. The Fifth Circuit found that the policy’s “criminal acts” exclusion  precluded coverage, despite the plaintiff not specifically pleading that the underlying acts were criminal: “Appellants have cited no case law stating that, to trigger a criminal act exclusion, the plaintiff in the underlying suit must, in addition to describing actions that necessarily imply a crime, also specifically label those actions as criminal. Such a rule is incongruous with the plain language of the Policy and would create an artifice in criminal-act exclusions.” No. 17-10026 (June 25, 2018).

precluded coverage, despite the plaintiff not specifically pleading that the underlying acts were criminal: “Appellants have cited no case law stating that, to trigger a criminal act exclusion, the plaintiff in the underlying suit must, in addition to describing actions that necessarily imply a crime, also specifically label those actions as criminal. Such a rule is incongruous with the plain language of the Policy and would create an artifice in criminal-act exclusions.” No. 17-10026 (June 25, 2018).

A pro se complaint in a mortgage servicing dispute stated a federal claim, and thus allowed removal, when “[I]n the ‘Facts’ section . . . [Plaintiffs’] wrote: ’17. In April, 2009 BANK OF AMERICA CORPORATION claimed to be the new mortgage servicer and payments were to be made to them. BANK OF AMERICA CORPORATION was not an “original party” to the “original negotiable instrument” which the “borrowers” negotiated. BANK OF AMERICA CORPORATION was a 3rd party debt collector, pretending to be the Lender. BANK OF AMERICA CORPORATION failed to adhere to the Fair Debt Collection Practice Act, as all 3rd party debt collectors are required to do.'” The Fifth Circuit observed: “[P]laintiffs may state a claim for relief by pleading facts that support the claim. The Smiths did just that—and cited the legal theory underlying their claim. The Smiths’ explicit reference to the ‘Fair Debt Collection Practice[s] Act’ (and its position in the U.S. Code), coupled with a description of conduct that could subject the Defendants to liability under the Act, solidifies our conclusion” about federal question jurisdiction. Smith v. Barrett Daffin Frappier Turner & Engel LLP, No. 16-51010 (June 12, 2018, unpublished).

A pro se complaint in a mortgage servicing dispute stated a federal claim, and thus allowed removal, when “[I]n the ‘Facts’ section . . . [Plaintiffs’] wrote: ’17. In April, 2009 BANK OF AMERICA CORPORATION claimed to be the new mortgage servicer and payments were to be made to them. BANK OF AMERICA CORPORATION was not an “original party” to the “original negotiable instrument” which the “borrowers” negotiated. BANK OF AMERICA CORPORATION was a 3rd party debt collector, pretending to be the Lender. BANK OF AMERICA CORPORATION failed to adhere to the Fair Debt Collection Practice Act, as all 3rd party debt collectors are required to do.'” The Fifth Circuit observed: “[P]laintiffs may state a claim for relief by pleading facts that support the claim. The Smiths did just that—and cited the legal theory underlying their claim. The Smiths’ explicit reference to the ‘Fair Debt Collection Practice[s] Act’ (and its position in the U.S. Code), coupled with a description of conduct that could subject the Defendants to liability under the Act, solidifies our conclusion” about federal question jurisdiction. Smith v. Barrett Daffin Frappier Turner & Engel LLP, No. 16-51010 (June 12, 2018, unpublished).

Various ripeness challenges to claims based on the Fourth, Fifth, and Fourteenth Amendments were rejected in the face of these remarkably strong facts: “Without prior notice, the City of New Orleans demolished a building along the IH-10 service road that plaintiffs had recently purchased at a tax sale. Yet two days before the demolition, the City actually cancelled the Code Enforcement lien on the property, which it obtained after sending notices only to the owner from 18 years earlier. When the Garretts objected to the demolition, the City added insult to injury by sending them a bill for the costs.” Archbold-Garrett v. City of New Orleans, No. 17-30692 (June 22, 2018).

Various ripeness challenges to claims based on the Fourth, Fifth, and Fourteenth Amendments were rejected in the face of these remarkably strong facts: “Without prior notice, the City of New Orleans demolished a building along the IH-10 service road that plaintiffs had recently purchased at a tax sale. Yet two days before the demolition, the City actually cancelled the Code Enforcement lien on the property, which it obtained after sending notices only to the owner from 18 years earlier. When the Garretts objected to the demolition, the City added insult to injury by sending them a bill for the costs.” Archbold-Garrett v. City of New Orleans, No. 17-30692 (June 22, 2018).

I think the server for this blog is located in Texas, but it could just as easily be on the South Pole – I have no control over (or interest in) how HostGator organizes its business. In the same spirit, the Fifth Circuit affirmed a personal jurisdiction dismissal in a trademark dispute between “greatfence.com” and “agreatfence.com“: “We need not decide today whether a web server’s location alone never suffices to establish personal jurisdiction. We simply hold that it cannot do so here, where there is no allegation, argument, or evidence that the defendants played any role in selecting the server’s location—or that its location was selected with the purpose or intent of facilitating the defendants’ business in the forum.” GreatFence.com v. Bailey, No. 17-20487 (June 13, 2018, unpublished) (emphasis in original).

I think the server for this blog is located in Texas, but it could just as easily be on the South Pole – I have no control over (or interest in) how HostGator organizes its business. In the same spirit, the Fifth Circuit affirmed a personal jurisdiction dismissal in a trademark dispute between “greatfence.com” and “agreatfence.com“: “We need not decide today whether a web server’s location alone never suffices to establish personal jurisdiction. We simply hold that it cannot do so here, where there is no allegation, argument, or evidence that the defendants played any role in selecting the server’s location—or that its location was selected with the purpose or intent of facilitating the defendants’ business in the forum.” GreatFence.com v. Bailey, No. 17-20487 (June 13, 2018, unpublished) (emphasis in original).

The “equal inference” rule has played an important role in Texas law about sufficiency of the evidence, especially after the memorable hypothetical in City of Keller v. Wilson, 168 S.W.3d 802, 814 (Tex. 2005): “Thus, for example, one might infer from cart tracks in spilled macaroni salad that it had been on the floor a long time, but one might also infer the opposite—that a sloppy shopper recently did both.” But that rule did not control in a slip-and-fall case involving the residue from an “autoscrubber” (right). The Fifth Circuit reasoned: “[Plaintiff’s] position is that the [security] video and Wal-Mart policies together suggest that (a) Wal-Mart used the machine to place slippery liquid on the floor, (b) the liquid was likely to collect in low-lying areas, (c) the machine paused over a low-lying area, (d) no Wal-Mart personnel checked for or took the requisite steps to remove it, and (e) [Plaintiff] slipped just where the machine had paused. This plausibly suggests the spill came from the auto-scrubber.” Garcia v. Wal-Mart, No. 17-20429 (June 18, 2018).

The “equal inference” rule has played an important role in Texas law about sufficiency of the evidence, especially after the memorable hypothetical in City of Keller v. Wilson, 168 S.W.3d 802, 814 (Tex. 2005): “Thus, for example, one might infer from cart tracks in spilled macaroni salad that it had been on the floor a long time, but one might also infer the opposite—that a sloppy shopper recently did both.” But that rule did not control in a slip-and-fall case involving the residue from an “autoscrubber” (right). The Fifth Circuit reasoned: “[Plaintiff’s] position is that the [security] video and Wal-Mart policies together suggest that (a) Wal-Mart used the machine to place slippery liquid on the floor, (b) the liquid was likely to collect in low-lying areas, (c) the machine paused over a low-lying area, (d) no Wal-Mart personnel checked for or took the requisite steps to remove it, and (e) [Plaintiff] slipped just where the machine had paused. This plausibly suggests the spill came from the auto-scrubber.” Garcia v. Wal-Mart, No. 17-20429 (June 18, 2018).

The Fifth Circuit issued a rare reversal in favor of an ERISA beneficiary in White v. Life Ins. Co. of N. Am. The issue was whether an “intoxication” exclusion applied; a doctor consulted by the plan administrator in its decision about benefits opined: “Since the only blood test done was an alcohol [test] that was negative and no blood tested for the presence of drugs, an estimation of Mr. White’s level of impairment cannot be done. The drugs present in his urine only show that he had prior exposure and cannot be used to estimate a level of impairment. Further, the drug screen that was done on Mr. White’s urine specimen only provided qualitative positive results.” The Court concluded that even though the insurer’s denial of benefits was supported by substantial evidence, its failure to expressly consider this report in its analysis (or to produce the report to the beneficiary’s estate until litigation) showed that its inherent conflict of interest had predominated and invalidated its denial. No. 17-30367 (revised June 14, 2018).

The Fifth Circuit issued a rare reversal in favor of an ERISA beneficiary in White v. Life Ins. Co. of N. Am. The issue was whether an “intoxication” exclusion applied; a doctor consulted by the plan administrator in its decision about benefits opined: “Since the only blood test done was an alcohol [test] that was negative and no blood tested for the presence of drugs, an estimation of Mr. White’s level of impairment cannot be done. The drugs present in his urine only show that he had prior exposure and cannot be used to estimate a level of impairment. Further, the drug screen that was done on Mr. White’s urine specimen only provided qualitative positive results.” The Court concluded that even though the insurer’s denial of benefits was supported by substantial evidence, its failure to expressly consider this report in its analysis (or to produce the report to the beneficiary’s estate until litigation) showed that its inherent conflict of interest had predominated and invalidated its denial. No. 17-30367 (revised June 14, 2018).

I am speaking this week at the 28th Annual Conference on State and Federal Appeals sponsored by the University of Texas School of Law; my topic is a “Fifth Circuit Update” and this is my PowerPoint.

I am speaking this week at the 28th Annual Conference on State and Federal Appeals sponsored by the University of Texas School of Law; my topic is a “Fifth Circuit Update” and this is my PowerPoint.

Illustrating the sort of highly specific, but highly practical, issues that arise under Twombly, the Fifth Circuit held that “plaintiffs alleging claims under [ERISA] § 1132(a)(1)(B) for plan benefits need not necessarily identify the specific language of every plan provision at issue to survive a motion to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6) (applying Electrostim Medical Services, Inc. v. Health Care Service Corp., 614 F. App’x 731 (5th Cir. 2015)). It was important to this holding that the plaintiff “was unable to obtain plan documents even after good-faith efforts to do so,” and the insurers “did not produce most of the relevant plan documents until the deadline to re-plead had passed . . . .” Innova Hospital v. Blue Cross, No. 14-11300 (June 12, 2018).

Illustrating the sort of highly specific, but highly practical, issues that arise under Twombly, the Fifth Circuit held that “plaintiffs alleging claims under [ERISA] § 1132(a)(1)(B) for plan benefits need not necessarily identify the specific language of every plan provision at issue to survive a motion to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6) (applying Electrostim Medical Services, Inc. v. Health Care Service Corp., 614 F. App’x 731 (5th Cir. 2015)). It was important to this holding that the plaintiff “was unable to obtain plan documents even after good-faith efforts to do so,” and the insurers “did not produce most of the relevant plan documents until the deadline to re-plead had passed . . . .” Innova Hospital v. Blue Cross, No. 14-11300 (June 12, 2018).

Huckaba signed an arbitration agreement with her employer, Ref-Chem – but Ref-Chem did not sign the agreement. The agreement had signature blocks for both parties, referred to the “signature affixed hereto” and the legal effect of “signing this agreement,” and also said that it “may not be changed, except in writing and signed by all parties.” The Fifth Circuit concluded that the agreement was not enforceable, focusing on the distinction between acceptance of the offer, and the separate requirement of “execution and delivery of the contract with intent that it be mutual and binding.” Huckaba v. Ref-Chem, L.P., No. 17-50341 (June 11, 2018).

Huckaba signed an arbitration agreement with her employer, Ref-Chem – but Ref-Chem did not sign the agreement. The agreement had signature blocks for both parties, referred to the “signature affixed hereto” and the legal effect of “signing this agreement,” and also said that it “may not be changed, except in writing and signed by all parties.” The Fifth Circuit concluded that the agreement was not enforceable, focusing on the distinction between acceptance of the offer, and the separate requirement of “execution and delivery of the contract with intent that it be mutual and binding.” Huckaba v. Ref-Chem, L.P., No. 17-50341 (June 11, 2018).

The insured’s commercial property insurance policy provided coverage from June 2, 2012 to June 2, 2013. “The summary judgment evidence reveals that several hail storms struck the vicinity of the hotel in the several years preceding [the insured’s] claim. Only one of these storms fell within the coverage period.” The Fifth Circuit found that the insured failed to establish coverage, even with an expert’s opinion that said a date within the period was “most likely,” when that opinion was later disclaimed and “conflicts with the data it purports to rely on.” Certain Underwriters v. Lowen Valley View LLC, No. 17-10914 (June 6, 2018).

The insured’s commercial property insurance policy provided coverage from June 2, 2012 to June 2, 2013. “The summary judgment evidence reveals that several hail storms struck the vicinity of the hotel in the several years preceding [the insured’s] claim. Only one of these storms fell within the coverage period.” The Fifth Circuit found that the insured failed to establish coverage, even with an expert’s opinion that said a date within the period was “most likely,” when that opinion was later disclaimed and “conflicts with the data it purports to rely on.” Certain Underwriters v. Lowen Valley View LLC, No. 17-10914 (June 6, 2018).

A lease dispute turned on the agreement’s effective date. The lease was found ambiguous on that point (and the subsequent trial result based on parol evidence affirmed), when it said:

A lease dispute turned on the agreement’s effective date. The lease was found ambiguous on that point (and the subsequent trial result based on parol evidence affirmed), when it said:

- On the last page – “IN WITNESS WHEREOF, the parties hereto have duly executed this Lease as of the day and year first written above.”

- And on the first page – “This Ground Lease (“Lease”), dated for reference purposes as ________, 2014, is made and executed by and between Malik and Sons, LLC (“Landlord”), and CIRCLE K STORES INC., a Texas corporation (“Tenant”).”

The Fifth Circuit concluded “Circle K offers a plausible interpretation, but Malik offers an alternative, credible interpretation to Circle K’s proposed interpretation. It seems equally—if not more likely—that the ‘day and year first written above’ is referencing a date the parties should have written on the last page. Therefore, although the last page references an execution date ‘written above,’ there is no date on that page. The only other date in the document is labeled as ‘for reference purposes.’ Even though Circle K is correct that parties ‘are free to specify the date of a contract’s execution,’ the issue here is whether they did.” Malik & Sons v. Circle K Stores, No. 17-30113 (May 15, 2018, unpublished).

“Litigation about litigation,” usually in the form of a federal suit to enjoin or otherwise overcome a state-court case, can involve complicated federalism concepts such as the Rooker-Feldman doctrine or Younger abstention. The Fifth Circuit reiterated an even more basic principle in Machetta v. Moren, in which an unhappy party to a state court child custody case sought to assert civil rights claims against the judges: “The district court [correctly] dismissed the case because no case or controversy exists between ‘a judge who adjudicates claims under a statute and a litigant who attacks the constitutionality of the statute.'” No. 17-20533 (June 4, 2018, unpublished).

“Litigation about litigation,” usually in the form of a federal suit to enjoin or otherwise overcome a state-court case, can involve complicated federalism concepts such as the Rooker-Feldman doctrine or Younger abstention. The Fifth Circuit reiterated an even more basic principle in Machetta v. Moren, in which an unhappy party to a state court child custody case sought to assert civil rights claims against the judges: “The district court [correctly] dismissed the case because no case or controversy exists between ‘a judge who adjudicates claims under a statute and a litigant who attacks the constitutionality of the statute.'” No. 17-20533 (June 4, 2018, unpublished).

A useful reminder about contract litigation appears in a recent insurance coverage dispute: “Neither party argues that the Hartford policy is ambiguous. Rather, the parties dispute whether the policy unambiguously provides coverage—Axis’s contention—or unambiguously excludes coverage—Hartford’s contention.” Bennett v. Hartford Ins. Co., No. 17-30311 (May 18, 2018) (emphasis in original).

A useful reminder about contract litigation appears in a recent insurance coverage dispute: “Neither party argues that the Hartford policy is ambiguous. Rather, the parties dispute whether the policy unambiguously provides coverage—Axis’s contention—or unambiguously excludes coverage—Hartford’s contention.” Bennett v. Hartford Ins. Co., No. 17-30311 (May 18, 2018) (emphasis in original).

A vigorously-litigated line  of Texas authority, often in the context of employment relationships defined by multiple documents, addresses whether an arbitration agreement is an illusory promise and thus unenforceable. In Arnold v. Homeaway, Inc. the Fifth Circuit addressed whether such a challenge went to “validity” (and could thus be resolved by an arbitrator under a “gateway” arbitration provision), or to “formation,” and could not. Drawing an analogy to Mississippi’s “minutes role” about the required documentation for contracts with public entities, the Court concluded that the challenge went to validity. Nos. 17-50088 and 17-50102 (May 15, 2018).

of Texas authority, often in the context of employment relationships defined by multiple documents, addresses whether an arbitration agreement is an illusory promise and thus unenforceable. In Arnold v. Homeaway, Inc. the Fifth Circuit addressed whether such a challenge went to “validity” (and could thus be resolved by an arbitrator under a “gateway” arbitration provision), or to “formation,” and could not. Drawing an analogy to Mississippi’s “minutes role” about the required documentation for contracts with public entities, the Court concluded that the challenge went to validity. Nos. 17-50088 and 17-50102 (May 15, 2018).

Flooded landowners in Houston alleged, inter alia, a violation of substantive due process from the effects of a “Reinvestment Zone” on drainage. Among other problems, that claim foundered on its merits under “rational basis” review: “Here, the government objectives were to improve its tax base and the general welfare. As stated by the plaintiffs in the complaint, the government projects enhanced roads and drainage, though in commercial areas in which the plaintiffs did not desire these improvements. The plaintiffs have also acknowledged in the complaint that ‘[t]he tax base has increased far above projections.’ It is ‘at least debatable’ that a rational relationship exists between the government projects and objectives.” Residents Against Flooding v. Reinvestment Zone No. 17, No. 17-20373 (May 22, 2018, unpublished).

Flooded landowners in Houston alleged, inter alia, a violation of substantive due process from the effects of a “Reinvestment Zone” on drainage. Among other problems, that claim foundered on its merits under “rational basis” review: “Here, the government objectives were to improve its tax base and the general welfare. As stated by the plaintiffs in the complaint, the government projects enhanced roads and drainage, though in commercial areas in which the plaintiffs did not desire these improvements. The plaintiffs have also acknowledged in the complaint that ‘[t]he tax base has increased far above projections.’ It is ‘at least debatable’ that a rational relationship exists between the government projects and objectives.” Residents Against Flooding v. Reinvestment Zone No. 17, No. 17-20373 (May 22, 2018, unpublished).

“Federal law does not prevent a bona fide shareholder from exercising its right to vote against a bankruptcy petition just because it is also an unsecured creditor. Under these circumstances, the issue of corporate authority to file a bankruptcy petition is left to state law.” Accordingly, when (a) the debtor is a Delaware corporation, (b) governed by that state’s General Corporation Law, and (c) nothing in that law would nullify the sole preferred shareholder’s right to vote against the bankruptcy petition, that shareholder has the right to vote against – and thus prevent – the corporation’s filing of a voluntary bankruptcy petition. Franchise Services. v. U.S. Trustee, No. 18-60093 (May 22, 2018).

“Federal law does not prevent a bona fide shareholder from exercising its right to vote against a bankruptcy petition just because it is also an unsecured creditor. Under these circumstances, the issue of corporate authority to file a bankruptcy petition is left to state law.” Accordingly, when (a) the debtor is a Delaware corporation, (b) governed by that state’s General Corporation Law, and (c) nothing in that law would nullify the sole preferred shareholder’s right to vote against the bankruptcy petition, that shareholder has the right to vote against – and thus prevent – the corporation’s filing of a voluntary bankruptcy petition. Franchise Services. v. U.S. Trustee, No. 18-60093 (May 22, 2018).

Before a lender may accelerate a debt (and later foreclose), Texas law requires that the lender send (1) notice of intent to accelerate, followed by (2) notice of acceleration. While “Texas courts have not squarely confronted whether a borrower is entitled to a new round of notice when a borrower re-accelerates following an earlier rescission,” the Fifth Circuit concluded “that the Texas Supreme Court would require such notice . . . Abandonment of acceleration ‘restor[es] the contract to its original condition.’ The Texas Supreme Court would likely conclude that Wilmington Trust acted ‘inconsistently’ by rescinding acceleration and then re-accelerating without notice.” Wilmington Trust v. Rob, No. 17-50115 (May 21, 2018).

Before a lender may accelerate a debt (and later foreclose), Texas law requires that the lender send (1) notice of intent to accelerate, followed by (2) notice of acceleration. While “Texas courts have not squarely confronted whether a borrower is entitled to a new round of notice when a borrower re-accelerates following an earlier rescission,” the Fifth Circuit concluded “that the Texas Supreme Court would require such notice . . . Abandonment of acceleration ‘restor[es] the contract to its original condition.’ The Texas Supreme Court would likely conclude that Wilmington Trust acted ‘inconsistently’ by rescinding acceleration and then re-accelerating without notice.” Wilmington Trust v. Rob, No. 17-50115 (May 21, 2018).

A Texas restaurateur took steps to open a seafood restaurant called The Krusty Krab. Those plans met choppy seas when Viacom, owner of the “SpongeBob SquarePants” TV show, sued to enforce its trademark rights as to that name (in the show, the undersea restaurant where SpongeBob works). In a textbook example of a Lanham Act claim (Texas common law being identical), the Fifth Circuit held:

A Texas restaurateur took steps to open a seafood restaurant called The Krusty Krab. Those plans met choppy seas when Viacom, owner of the “SpongeBob SquarePants” TV show, sued to enforce its trademark rights as to that name (in the show, the undersea restaurant where SpongeBob works). In a textbook example of a Lanham Act claim (Texas common law being identical), the Fifth Circuit held:

- As a threshold matter, specific elements of a TV show can receive trademark protection (citing Conan the Barbarian, the General Lee, and Kryponite, while noting the less-fortunate case law about the Star Trek franchise’s rights to the term “Romulan”)

- As to the first element, the mark is legally protectable, especially given the high profile and longevity of the SpongeBob show

- And as to the second element, despite some uncertainty as to its degree and nature, the likelihood of confusion was still high enough to justify trademark protection.

Viacom Int’l v. IJR Capital Investments, No. 17-20334 (May 22, 2018).

Plaintiff argued, for purposes of a UCC Article 2 damages calculation, that a pollution monitoring system was worthless because it was not practically repairable. The Fifth Circuit disagreed – language in an earlier Mississippi case about whether a good “could not be repaired and was worthless” was not “the same as ‘the goods were worthless because they could not be repaired.’ While it is true that an unrepairable good may also be worthless, it does not follow that such a good is always worthless.” The Court also found, as to a limitation-of-remedy provision: “Here, Altech provided an exclusive repair or replace warranty. The warranty failed of its essential purpose when Altech—over the course of years—was continually unable to repair the [system].” Steel Dynamics v. Alltech Environment, No. 17-60298 (May 17, 2018, unpublished).

Plaintiff argued, for purposes of a UCC Article 2 damages calculation, that a pollution monitoring system was worthless because it was not practically repairable. The Fifth Circuit disagreed – language in an earlier Mississippi case about whether a good “could not be repaired and was worthless” was not “the same as ‘the goods were worthless because they could not be repaired.’ While it is true that an unrepairable good may also be worthless, it does not follow that such a good is always worthless.” The Court also found, as to a limitation-of-remedy provision: “Here, Altech provided an exclusive repair or replace warranty. The warranty failed of its essential purpose when Altech—over the course of years—was continually unable to repair the [system].” Steel Dynamics v. Alltech Environment, No. 17-60298 (May 17, 2018, unpublished).

Carley and Brown, the plaintiffs in a case about overtime pay, drove a Ford F-350 in their work as “cementers” for oil wells. The threshold question was whether the truck was a “motor vehicle[] weighing10,000 pounds or less”; if it was, a federal statute would remove them from overtime requirements. While seemingly clear, the statute left open the important practical matters, requiring the Fifth Circuit to analyze it and conclude:

Carley and Brown, the plaintiffs in a case about overtime pay, drove a Ford F-350 in their work as “cementers” for oil wells. The threshold question was whether the truck was a “motor vehicle[] weighing10,000 pounds or less”; if it was, a federal statute would remove them from overtime requirements. While seemingly clear, the statute left open the important practical matters, requiring the Fifth Circuit to analyze it and conclude:

- What. Applying Skidmore deference to a Labor Department bulleting about the statute, “weight” specifically refers to the manufacturer’s specified “gross vehicle weight rating”;

- Who. So defined, the burden of proof about “weight” fell on Carley, as this statute “is . . . not an exemption . . . [but] rather, it codifies conditions under which” pay is required notwithstanding an exemption; and

- How. Echoing similar disputes about the relevance of property tax filings in valuation disputes, a document about vehicle registration, that stated the truck’s “empty weight” (7600 pounds) and “gross weight” (9600 pounds) did not overcome undisputed evidence that the GVWR was in fact 11,500 pounds.

Carley v. Crest Pumping Technologies, No. 17-50226 (May 16, 2018).

Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins was decided in 1938. Sierra Equipment v. Lexington Ins. Co., an Erie case from the Fifth Circuit this week, turned on Texas authority that pre-dated Erie – specifically, a court of appeals opinion approved by the 1920s-era Texas Commission on Appeals (a representative picture of which is to the right). The specific question was whether the “equitable lien” doctrine allowed a lessee to sue on a lessor’s insurance policy absent a “loss payable” clause in the policy; consistent with the ruling of the Commission and most other cases on the point, the Court concluded that the lessee could not bring that suit. No. 17-10076 (May 15, 2018).

Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins was decided in 1938. Sierra Equipment v. Lexington Ins. Co., an Erie case from the Fifth Circuit this week, turned on Texas authority that pre-dated Erie – specifically, a court of appeals opinion approved by the 1920s-era Texas Commission on Appeals (a representative picture of which is to the right). The specific question was whether the “equitable lien” doctrine allowed a lessee to sue on a lessor’s insurance policy absent a “loss payable” clause in the policy; consistent with the ruling of the Commission and most other cases on the point, the Court concluded that the lessee could not bring that suit. No. 17-10076 (May 15, 2018).

The triangular relationship between (1) an insurer, (2) an insured, and (3) the counsel chosen by the insurer to defend the insured in litigation can become an uneasy one. Grain Dealers Mut. Ins. Co. v. Cooley illustrates when it can become unstable. The insurer (Grain Dealers) provided the insureds (the Cooleys) a defense, “yet simultaneously disclaimed coverage if the Cooleys were ordered to clean the spill. In doing so, Grain Dealers failed to inform the Cooleys of their right to hire independent counsel. When the [relevant administrative agency] ultimately found the Cooleys liable for the spill, Grain Dealers then refused to defend or indemnify the Cooleys against a resulting claim.” That failure created the prejudice needed to estop Grain Dealers from denying coverage for liability: ” [T]he Cooleys presented evidence that Grain Dealers’ attorney never informed them of their right to challenge the [agency] decision. That right has since lapsed. The loss of the right to challenge the underlying administrative order with the benefit of non-conflicted counsel is clearly prejudicial.” No. 17-60307 (May 14, 2017, unpublished).

The triangular relationship between (1) an insurer, (2) an insured, and (3) the counsel chosen by the insurer to defend the insured in litigation can become an uneasy one. Grain Dealers Mut. Ins. Co. v. Cooley illustrates when it can become unstable. The insurer (Grain Dealers) provided the insureds (the Cooleys) a defense, “yet simultaneously disclaimed coverage if the Cooleys were ordered to clean the spill. In doing so, Grain Dealers failed to inform the Cooleys of their right to hire independent counsel. When the [relevant administrative agency] ultimately found the Cooleys liable for the spill, Grain Dealers then refused to defend or indemnify the Cooleys against a resulting claim.” That failure created the prejudice needed to estop Grain Dealers from denying coverage for liability: ” [T]he Cooleys presented evidence that Grain Dealers’ attorney never informed them of their right to challenge the [agency] decision. That right has since lapsed. The loss of the right to challenge the underlying administrative order with the benefit of non-conflicted counsel is clearly prejudicial.” No. 17-60307 (May 14, 2017, unpublished).

Congratulations and every best wish to new Fifth Circuit judge Kurt Engelhardt of New Orleans, formerly the Chief Judge of the Eastern District of Louisiana, who was confirmed yesterday by the Senate. Fifteen of the Court’s seventeen positions for full-time judges are now filled, with the nomination of Texas’s Andrew Oldham pending, and the seat formerly held by Judge Jolly still vacant.

Congratulations and every best wish to new Fifth Circuit judge Kurt Engelhardt of New Orleans, formerly the Chief Judge of the Eastern District of Louisiana, who was confirmed yesterday by the Senate. Fifteen of the Court’s seventeen positions for full-time judges are now filled, with the nomination of Texas’s Andrew Oldham pending, and the seat formerly held by Judge Jolly still vacant.

Among other (unsuccessful) challenges to the exclusion of summary judgment evidence, the appellant in Warren v. Fannie Mae invoked Mutual Life Ins. Co. of New York v. Hillmon, 145 U.S. 285 (1892), the case that led to the hearsay exception in Fed. R. Evid. 803(3) for “then-existing mental, emotional, or physical condition.” (The opinion was

Among other (unsuccessful) challenges to the exclusion of summary judgment evidence, the appellant in Warren v. Fannie Mae invoked Mutual Life Ins. Co. of New York v. Hillmon, 145 U.S. 285 (1892), the case that led to the hearsay exception in Fed. R. Evid. 803(3) for “then-existing mental, emotional, or physical condition.” (The opinion was  written by Justice Horace Gray, right). The citation did not succeed, however, as the Fifth Circuit observed: “Hillmon looked at a declarant’s words as evidence they later followed through with a plan. Warren is arguing that her post-conduct statements of intention imply that she actually told Peters about Finch. Therefore, Hillmon is inapposite.” No. 17-10567 (May 3, 2018, unpublished).

written by Justice Horace Gray, right). The citation did not succeed, however, as the Fifth Circuit observed: “Hillmon looked at a declarant’s words as evidence they later followed through with a plan. Warren is arguing that her post-conduct statements of intention imply that she actually told Peters about Finch. Therefore, Hillmon is inapposite.” No. 17-10567 (May 3, 2018, unpublished).

The Fifth Circuit affirmed the denial of a motion to dismiss under the TCPA (the Texas “anti-SLAPP” statute), noting that the appellant’s arguments to the district court limited him to “only . . . the theory that the TCPA applies because the claims are based on, related to, or in response to a communication in or pertaining to a judicial proceeding” within the meaning of that statute. The appellant submitted a Rule 28(j) letter citing a recent Texas Supreme Court opinion that, inter alia, recommended a “holistic review of the pleadings” in the TCPA context. The Fifth Circuit did not agree, characterizing this “point, at its core, [a]s the Texas Supreme Court’s application of that court’s argument waiver principles,” and observing: “Because this court consistently applies its waiver precedent in diversity jurisdiction cases, we will do so here.” Diamond Consortium, Inc. v. Hammervold, No.17-40582 (May 3, 2018).

The Fifth Circuit affirmed the denial of a motion to dismiss under the TCPA (the Texas “anti-SLAPP” statute), noting that the appellant’s arguments to the district court limited him to “only . . . the theory that the TCPA applies because the claims are based on, related to, or in response to a communication in or pertaining to a judicial proceeding” within the meaning of that statute. The appellant submitted a Rule 28(j) letter citing a recent Texas Supreme Court opinion that, inter alia, recommended a “holistic review of the pleadings” in the TCPA context. The Fifth Circuit did not agree, characterizing this “point, at its core, [a]s the Texas Supreme Court’s application of that court’s argument waiver principles,” and observing: “Because this court consistently applies its waiver precedent in diversity jurisdiction cases, we will do so here.” Diamond Consortium, Inc. v. Hammervold, No.17-40582 (May 3, 2018).

In Gulf Coast Workforce LLC v. Zurich American Ins. Co., the appellant’s “second point of error alleges that the district court awarded damages that no witness could explain or confirm. Zurich’s sole witness was Smith, who conducted the audit but did not work on billing matters. [Appellant] contends that, because Smith could not testify to the $53,161 premium, Zurich did not prove its damages.” The Fifth Circuit saw otherwise, identifying two trial exhibits that supported that figure and holding: “Therefore, the district court’s damages determination was not clearly erroneous.” No. 17-30379 (May 4, 2018, unpublished).

In Gulf Coast Workforce LLC v. Zurich American Ins. Co., the appellant’s “second point of error alleges that the district court awarded damages that no witness could explain or confirm. Zurich’s sole witness was Smith, who conducted the audit but did not work on billing matters. [Appellant] contends that, because Smith could not testify to the $53,161 premium, Zurich did not prove its damages.” The Fifth Circuit saw otherwise, identifying two trial exhibits that supported that figure and holding: “Therefore, the district court’s damages determination was not clearly erroneous.” No. 17-30379 (May 4, 2018, unpublished).

Another practice point from In re DePuy Orthopaedics involved this portion of the plaintiffs’ closing argument, allowed over objection and without any accompanying instruction: “If you don’t consider the damages by the day, by the hour, by the minute, then you haven’t considered their damages. . . . “[P]lease, please, please, if they [the defendants] will pay their experts a thousand dollars an hour to come in here, when you do your math back there don’t tell these plaintiffs that a day in their life is worth less than an hour’s time of this fellow, or people they put on the stand.”

Another practice point from In re DePuy Orthopaedics involved this portion of the plaintiffs’ closing argument, allowed over objection and without any accompanying instruction: “If you don’t consider the damages by the day, by the hour, by the minute, then you haven’t considered their damages. . . . “[P]lease, please, please, if they [the defendants] will pay their experts a thousand dollars an hour to come in here, when you do your math back there don’t tell these plaintiffs that a day in their life is worth less than an hour’s time of this fellow, or people they put on the stand.”

The Fifth Circuit observed: “[U]unit-of-time arguments like this one are impermissible because they can lead the jury to ‘believ[e] that the determination of a proper award for . . . pain and suffering is a matter of precise and accurate determination and not, as it really is, a matter to be left to the jury’s determination, uninfluenced by arguments and charts.’ Lanier’s reference to expert fees was meant simultaneously to activate the jury’s passions and to anchor their minds to a salient, inflated, and irrelevant dollar figure. The inflammatory benchmark, bearing no rational relation to plaintiffs’ injuries, easily amplified the risk of ‘an excessive verdict.’ The argument was ‘design[ed] to mislead,’ and tainted the verdict that followed.” Nos. 16-11051 et seq. (April 25, 2018) (citations omitted).

The panel majority in Benson v. Tyson Foods affirmed the denial of a request to speak to jurors after a trial, but observed: “In light of the First Amendment interests at stake here, which [Haeberle v. Texas Int’l Airlines, 739 F.2d 1019 (5th Cir. 1984)] did not appear to fully appreciate, district courts in the future would be wise to consider seriously whether there exists any genuine government interest in preventing attorneys from conversing with consenting jurors—and if so, whether that interest should be specifically articulated, in order to facilitate appellate review and fidelity to the Constitution.” A concurring opinion agreed with the affirmance but would not have relied on the Haeberle opinion, instead preferring an approach that took into account the interests of the movant as a factor – a “step . . . fatal to Benson’s argument,” as “her rights would be unaffected by a decision that the district court abused its discretion in not giving her counsel sufficient justification for denying their request.” No. 17-40161 (May 1, 2018).

The panel majority in Benson v. Tyson Foods affirmed the denial of a request to speak to jurors after a trial, but observed: “In light of the First Amendment interests at stake here, which [Haeberle v. Texas Int’l Airlines, 739 F.2d 1019 (5th Cir. 1984)] did not appear to fully appreciate, district courts in the future would be wise to consider seriously whether there exists any genuine government interest in preventing attorneys from conversing with consenting jurors—and if so, whether that interest should be specifically articulated, in order to facilitate appellate review and fidelity to the Constitution.” A concurring opinion agreed with the affirmance but would not have relied on the Haeberle opinion, instead preferring an approach that took into account the interests of the movant as a factor – a “step . . . fatal to Benson’s argument,” as “her rights would be unaffected by a decision that the district court abused its discretion in not giving her counsel sufficient justification for denying their request.” No. 17-40161 (May 1, 2018).

In re DePuy Orthopaedics also warns against driving through much traffic through an “opened door” for the admission of evidence, noting:

In re DePuy Orthopaedics also warns against driving through much traffic through an “opened door” for the admission of evidence, noting:

The district court admitted several pieces of inflammatory character evidence against defendants—including claims of race discrimination and bribes to Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi “regime”—reasoning the defendants had “opened the door” by repeatedly presenting themselves as “wonderful people doing wonderful things.”

. . .

The district court allowed these repeated references to Hussein and the [Deferred Prosecution Agreement] because

defendants had supposedly “opened the door” by eliciting testi-mony on their corporate culture and marketing practices. This justification is strained, given that J&J owns more than 265 companies in 60 countries, and the Iraqi portion of the DPA addresses conduct by non-party subsidiaries. “[T]he Rules of Evidence do not simply evaporate when one party opens the door on an issue.”

Nos. 16-11051 et seq. (April 25, 2018) (citations omitted, emphasis added).

Among other holdings in In re DePuy Orthopaedics, the Fifth Circuit observed: “Suppose we did believe [counsel]’s various and independent explanations for why he could pay his expert before and after trial without ever compromising the witness’s non-retained status. An opinion countenancing his behavior would read like a blueprint on how to evade Rule 26 with impunity. Parties could pay experts ‘for their time’ before trial and later exchange compelling ‘pro bono’ testimony for sizable, post-trial ‘thank you’ checks.” No. 16-11051 et seq. (April 25, 2018) (emphasis in original).

At a recent energy law seminar for the University of Texas, My colleagues Michael Hurst, Jonathan Childers, and Jervonne Newsome presented this excellent paper on the important and recurring topic of maintaining attorney-client privilege in communications involving in-house counsel – a constant challenge given the many hats worn by legal counsel in the modern business environment.

At a recent energy law seminar for the University of Texas, My colleagues Michael Hurst, Jonathan Childers, and Jervonne Newsome presented this excellent paper on the important and recurring topic of maintaining attorney-client privilege in communications involving in-house counsel – a constant challenge given the many hats worn by legal counsel in the modern business environment.

The Senate has confirmed Louisiana’s Kyle Duncan to a New Orleans-based seat on the Fifth Circuit, bringing the Court one step closer to a long-awaited full roster of active-duty judges. Every best wish to Judge Duncan.

The Senate has confirmed Louisiana’s Kyle Duncan to a New Orleans-based seat on the Fifth Circuit, bringing the Court one step closer to a long-awaited full roster of active-duty judges. Every best wish to Judge Duncan.

A lawyer sought to appeal a sanctions order; the Fifth Circuit found that it lacked appellate jurisdiction:

A lawyer sought to appeal a sanctions order; the Fifth Circuit found that it lacked appellate jurisdiction:

- The Court did not accept the district court’s certification under Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(b), as “the claim for relief is the wrongful death and survival cause of action brought by [Plaintiff] . . . [t]he Rule 11 sanctions and referral to the disciplinary committee with findings of . . . misconduct are not claims for relief in this suit”;

- The district court’s Rule 54 order did not contain a certification about “a legal issue that satisfies the substantive requirements of § 1292(b),” and thus could not be treated as an appealable interlocutory order;

- The sanctions ruling was not a “collateral order,” as it is “reviewable after the district court makes its determinations of liability on the merits . . . .”; and

- A potentially-viable doctrine about the appeal of sanctions orders, combined with an attorney’s withdrawal, did not apply because the relevant counsel remained in the case

Nogess v. Poydras Center LLC, No. 17-30449 (April 3, 2018).

Donald Rumsfel d unforgettably spoke about known unknowns. The Fifth Circuit engaged that general concept in Bartolowits v. Wells Fargo, in which the plaintiff claimed that a lender “misrepresented the amount [plaintiff] owed and its security interest in his property to a state court in seeking a foreclosure order.” But on the issue of “whether Wells Fargo committed fraud by claiming the right to foreclose on unsecured property,” the Court found that he could not have justifiably relied on this statement “because he knew that Wells Fargo lacked a security interest in some of the property it sought to foreclose upon” (indeed, at the time, the plaintiff denied Wells’s allegations and notified Wells of the error). In sum: “There is no justifiable reliance when the misrepresentations contradict a fact known by the plaintiff.” No. 17-10434 (April 4, 2018, unpublished).

d unforgettably spoke about known unknowns. The Fifth Circuit engaged that general concept in Bartolowits v. Wells Fargo, in which the plaintiff claimed that a lender “misrepresented the amount [plaintiff] owed and its security interest in his property to a state court in seeking a foreclosure order.” But on the issue of “whether Wells Fargo committed fraud by claiming the right to foreclose on unsecured property,” the Court found that he could not have justifiably relied on this statement “because he knew that Wells Fargo lacked a security interest in some of the property it sought to foreclose upon” (indeed, at the time, the plaintiff denied Wells’s allegations and notified Wells of the error). In sum: “There is no justifiable reliance when the misrepresentations contradict a fact known by the plaintiff.” No. 17-10434 (April 4, 2018, unpublished).

Making a not-so-subtle remark about the requirements for a successful en banc petition, the Fifth Circuit has amended local rule 35.5 to say: “35.5 Length. See Fed. R. App. P. 35(b)(2). The statement required by Fed. R. App. P. 35(b)(1) is included in the limit and is not a “certificate[ ] of counsel” that is excluded by Fed. R. App P. 32(f).” In other words, the certificate of counsel about the specific cases inconsistent with the panel opinion counts against the length limit.

Making a not-so-subtle remark about the requirements for a successful en banc petition, the Fifth Circuit has amended local rule 35.5 to say: “35.5 Length. See Fed. R. App. P. 35(b)(2). The statement required by Fed. R. App. P. 35(b)(1) is included in the limit and is not a “certificate[ ] of counsel” that is excluded by Fed. R. App P. 32(f).” In other words, the certificate of counsel about the specific cases inconsistent with the panel opinion counts against the length limit.

Nester v. Textron, Inc. affirmed a judgment for the plaintiff in a products liability case, arising from a gruesome accident involving a golf-cart like utility vehicle. In reviewing challenges to the jury charge, theFifth Circuit discussed in detail two important issues:

Nester v. Textron, Inc. affirmed a judgment for the plaintiff in a products liability case, arising from a gruesome accident involving a golf-cart like utility vehicle. In reviewing challenges to the jury charge, theFifth Circuit discussed in detail two important issues:

- PJC Power. A state’s approved pattern jury instructions are presumptively correct, especially when the record shows a lack of harm: “Federal judges often face the workaday dilemma of how much state law to consolidate expressly into the jury charge. . . . The list of conceivable additions goes on. But, as our prior cases indiate, a commonly administered PJC is often an entirely sensible place to draw the line. . . . At the end of the day, Textron asks us to hold that the district court erred by

refusing to deviate from a standard Texas instruction. That definition permitted Textron to make its arguments about various tradeoffs to the jury (it did so) and gave those jurors a means to find in Textron’s favor (they balked).”

refusing to deviate from a standard Texas instruction. That definition permitted Textron to make its arguments about various tradeoffs to the jury (it did so) and gave those jurors a means to find in Textron’s favor (they balked).” - Casteel, federal-style. After a thorough (and infrequently-seen) summary of how federal law has developed on the “Casteel problem” of commingled liability theories, the Court concluded: “We will not reverse a verdict simply because the jury might have decided on a ground that was supported by insufficient evidence.” (applying, inter alia, Griffin v. United States, 502 U.S. 46 (1991)).

No. 16-5115 (April 18, 2018).

Under Louisiana law, while “fugitive minerals” cannot be conveyed, “this principle by no means forbids a landowner or lessee from conveying pre-extraction mineral interests”;

Under Louisiana law, while “fugitive minerals” cannot be conveyed, “this principle by no means forbids a landowner or lessee from conveying pre-extraction mineral interests”;- An “overriding royalty interest” is a property interest, not “a mere interest in proceeds” from production; and

- The “safe harbor” provision in the Louisiana Oil Well Lien Act protected a party’s liens on a debtor’s overriding royalty interests – while that statute “may not be a model of clarity,” its reference to “hydrocarbons” includes such interests, when viewed in the complete context of the Louisiana property statutes.

OHA Investment Corp. v. Schlumberger Tech. Corp., No. 17-20224 (April 17, 2018).

Comcast loaned $100 million to a sports television network, secured by a lien on substantially all the network’s assets. When the network had financial problems, Comcast entities placed it into an involuntary Chapter 11 proceeding. The Fifth Circuit reversed on, inter alia, a subtle but very significant point – at what point in time should unpaid media fees be valued, to credit against the potential value to Comcast of a valuable agreement? The Court concluded that “a court is not required to use either the petition date or the effective date,” but should rather “follow a flexible approach to valuation timing that allows the bankruptcy court to take into account the development of the proceedings, as the value of the collateral may vary dramatically based on its proposed use under any given plan.” Houston SportsNet Finance LLC v. Houston Astros LLC, No. 15-20497 (March 29, 2018).

Comcast loaned $100 million to a sports television network, secured by a lien on substantially all the network’s assets. When the network had financial problems, Comcast entities placed it into an involuntary Chapter 11 proceeding. The Fifth Circuit reversed on, inter alia, a subtle but very significant point – at what point in time should unpaid media fees be valued, to credit against the potential value to Comcast of a valuable agreement? The Court concluded that “a court is not required to use either the petition date or the effective date,” but should rather “follow a flexible approach to valuation timing that allows the bankruptcy court to take into account the development of the proceedings, as the value of the collateral may vary dramatically based on its proposed use under any given plan.” Houston SportsNet Finance LLC v. Houston Astros LLC, No. 15-20497 (March 29, 2018).

In Alice in Wonderland, the Mad Hatter remarked: “If I had a world of my own . . . Nothing would be what it is, because everything would be what it isn’t. And contrary wise, what is, it wouldn’t be. And what it wouldn’t be, it would. You see?” In that spirit, under 28 U.S.C. § 1447(d), a remand order is unreviewable on appeal if issued under one of the grounds in § 1447(c) – either a lack of subject matter jurisdiction, or the plaintiff moves ” to remand the case on the basis of any defect other than lack of subject matter jurisdiction . . . within 30 days after the filing of the notice of removal.” In Exxon Mobil Corp. v. Starr Indemnity, the plaintiff argued that the district court erred by remanding based on subject matter jurisdiction, when the issue before it was properly characterized as a late-raised procedural matter. The Fifth Circuit agreed, but held: “[Defendants], however, cannot evade the reviewability bar of § 1447(d) by establishing this defect. . . . . Indeed, each passage from the district court’s order to which the Insurers point as a clear and affirmative statement of a non-§ 1447(c) ground in fact expressly invokes that court’s perceived lack of subject matter jurisdiction. This belief, however erroneous, ‘sufficiently cloaks the remand order in the § 1447(c) absolute immunity from review’ and ends the inquiry.” No. 16-20821 (March 26, 2018, unpublished).

In Alice in Wonderland, the Mad Hatter remarked: “If I had a world of my own . . . Nothing would be what it is, because everything would be what it isn’t. And contrary wise, what is, it wouldn’t be. And what it wouldn’t be, it would. You see?” In that spirit, under 28 U.S.C. § 1447(d), a remand order is unreviewable on appeal if issued under one of the grounds in § 1447(c) – either a lack of subject matter jurisdiction, or the plaintiff moves ” to remand the case on the basis of any defect other than lack of subject matter jurisdiction . . . within 30 days after the filing of the notice of removal.” In Exxon Mobil Corp. v. Starr Indemnity, the plaintiff argued that the district court erred by remanding based on subject matter jurisdiction, when the issue before it was properly characterized as a late-raised procedural matter. The Fifth Circuit agreed, but held: “[Defendants], however, cannot evade the reviewability bar of § 1447(d) by establishing this defect. . . . . Indeed, each passage from the district court’s order to which the Insurers point as a clear and affirmative statement of a non-§ 1447(c) ground in fact expressly invokes that court’s perceived lack of subject matter jurisdiction. This belief, however erroneous, ‘sufficiently cloaks the remand order in the § 1447(c) absolute immunity from review’ and ends the inquiry.” No. 16-20821 (March 26, 2018, unpublished).

A photographer sued a business for using his copyrighted pictures. The defendant assert its licensing rights as a defense; specifically, as a sublicensee of the industry group that obtained a license from the photographer. The Fifth Circuit observed: “The right to bring a copyright infringement action comes from federal copyright law,” which is “a separate question from whether [the defendant] can prove (under state law)

A photographer sued a business for using his copyrighted pictures. The defendant assert its licensing rights as a defense; specifically, as a sublicensee of the industry group that obtained a license from the photographer. The Fifth Circuit observed: “The right to bring a copyright infringement action comes from federal copyright law,” which is “a separate question from whether [the defendant] can prove (under state law)  that it has a meritorious license defense. Based on that observation, the Court concluded that the district court had incorrectly conflated the plaintiff’s right to sue on the license under state law with its standing to raise copyright claims under federal law, and reversed a summary judgment for the defendant. As to the scope of the sublicense, the Court found a triable fact issue presented by an affiant’s assertion about the duration of that license, which was not completely supported by the dates on the documents submitted with that affidavit. Stross v. Redfin Corp., No. 17-50046 (April 9, 2018) (While issued per curiam, certain turns of phrase in the opinion suggest the handiwork of newly-arrived Judge Willett, who was on the panel.)

that it has a meritorious license defense. Based on that observation, the Court concluded that the district court had incorrectly conflated the plaintiff’s right to sue on the license under state law with its standing to raise copyright claims under federal law, and reversed a summary judgment for the defendant. As to the scope of the sublicense, the Court found a triable fact issue presented by an affiant’s assertion about the duration of that license, which was not completely supported by the dates on the documents submitted with that affidavit. Stross v. Redfin Corp., No. 17-50046 (April 9, 2018) (While issued per curiam, certain turns of phrase in the opinion suggest the handiwork of newly-arrived Judge Willett, who was on the panel.)

Many years, ago, “the Supreme Court viewed the fashioning of statutory remedies as within the property judicial rule [u]nder the now-abandoned maxim that ‘a statutory right implies the existence of all necessary and appropriate remedies.'” But that view has changed, and now, “the judicial task is to interpret the statute Congress has passed.” Alexander v. Sandoval, 532 U.S. 275 (2001). Proceeding from that starting point, after a review of the text and structure of the Air Carrier Access Act of 1986, the Court agreed that the Act did not create a private right of action, and it recognized that earlier Circuit authority on the issue had been essentially overruled by the analytical framework in Sandoval. Stokes v. Southwest Airlines, No. 17-10760 (April 5, 2018).

Many years, ago, “the Supreme Court viewed the fashioning of statutory remedies as within the property judicial rule [u]nder the now-abandoned maxim that ‘a statutory right implies the existence of all necessary and appropriate remedies.'” But that view has changed, and now, “the judicial task is to interpret the statute Congress has passed.” Alexander v. Sandoval, 532 U.S. 275 (2001). Proceeding from that starting point, after a review of the text and structure of the Air Carrier Access Act of 1986, the Court agreed that the Act did not create a private right of action, and it recognized that earlier Circuit authority on the issue had been essentially overruled by the analytical framework in Sandoval. Stokes v. Southwest Airlines, No. 17-10760 (April 5, 2018).

In Stevens v. Belhaven University, the Fifth Circuit described a set of findings that justified a $500 sanctions award on a client and $100 on a lawyer (adding numbers and headings for ease of reference):

In Stevens v. Belhaven University, the Fifth Circuit described a set of findings that justified a $500 sanctions award on a client and $100 on a lawyer (adding numbers and headings for ease of reference):

(1. Preservation letter) The court explained that counsel had received a letter demanding him to “preserve and sequester” the phone.

(2. Failure to preserve) The defendant “was therefore sur-prised to learn . . . that the phone had broken and was no longer in [plaintiff’s] possession [but] had been taken . . . to a local AT&T store [where] she pur-chased a new phone.”

(3. Lack of explanation) “In her deposition, [plaintiff] could not explain how some of the text messages were deleted from her phone before they were shared with the EEOC.”

(4. Actual relevance of material at issue.) “When [she] did search her iCloud, moreover―. . . she identified new, material, and important evidence.

(5. In addition to (3), inconsistent explanation.) That . . . directly contradicts [her] ear-lier sworn statement that she had produced everything to [the defendant].”

No. 17-60652 (April 2, 2018, unpublished).

In In re Drummond, the Fifth Circuit granted a writ of mandamus to require a trial court ruling on two long-dormant motions. It reasoned: “‘A writ of mandamus may issue only if (1) the petitioner has “no other adequate means” to attain the desired relief; (2) the petitioner has demonstrated a right to the issuance of a writ that is “clear and indisputable;” and (3) the issuing court, in the exercise of its discretion, is satisfied that the writ is “appropriate under the circumstances.”‘ In this case, all three requirements are easily met. This case has been pending on the district court’s docket for over nine years. Moreover, the two motions identified in the petition have been pending for approximately four years. We recognize that this is a complex matter and district court judges have broad discretion in managing their dockets. ‘However, discretion has its limits.'” No. 17-20618 (March 23, 2018) (citations omitted). (By way of comparison, I was involved in a similar mandamus petition in the El Paso Court of Appeals, In re: Mesa Petroleum Partners, No. 08-17-00095-CV (Nov. 9, 2017)).

In In re Drummond, the Fifth Circuit granted a writ of mandamus to require a trial court ruling on two long-dormant motions. It reasoned: “‘A writ of mandamus may issue only if (1) the petitioner has “no other adequate means” to attain the desired relief; (2) the petitioner has demonstrated a right to the issuance of a writ that is “clear and indisputable;” and (3) the issuing court, in the exercise of its discretion, is satisfied that the writ is “appropriate under the circumstances.”‘ In this case, all three requirements are easily met. This case has been pending on the district court’s docket for over nine years. Moreover, the two motions identified in the petition have been pending for approximately four years. We recognize that this is a complex matter and district court judges have broad discretion in managing their dockets. ‘However, discretion has its limits.'” No. 17-20618 (March 23, 2018) (citations omitted). (By way of comparison, I was involved in a similar mandamus petition in the El Paso Court of Appeals, In re: Mesa Petroleum Partners, No. 08-17-00095-CV (Nov. 9, 2017)).

In 16 Front Street v. Mississippi Silicon, the Fifth Circuit addressed a fundamental issue about federal question subject matter jurisdiction, with surprisingly little guidance in the current case law. A plaintiff sued in federal court under the Clean Air Act; in response to the trial judge’s concerns about subject matter jurisdiction, the plaintiff amended to add a new defendant and invoke another provision of that Act. The Fifth Circuit concluded that while this amendment could be problematic in a removed case under the “time-of-filing” rule, it did not present that problem when the case was initially filed in federal court and did not implicate the removal statute. The Court’s analysis involves two important Supreme Court – Mollan v. Torrance, 22 U.S. 537 (1824), in which Chief Justice Marshall first stated the “time-of-filing” rule (albeit, in a diversity case), and Caterpillar, Inc. v. Lewis, 519 U.S. 61 (19960, a recent treatment of a “cure” of a problem with subject matter jurisdiction. No. 16-60050 (March 30, 2018).

In 16 Front Street v. Mississippi Silicon, the Fifth Circuit addressed a fundamental issue about federal question subject matter jurisdiction, with surprisingly little guidance in the current case law. A plaintiff sued in federal court under the Clean Air Act; in response to the trial judge’s concerns about subject matter jurisdiction, the plaintiff amended to add a new defendant and invoke another provision of that Act. The Fifth Circuit concluded that while this amendment could be problematic in a removed case under the “time-of-filing” rule, it did not present that problem when the case was initially filed in federal court and did not implicate the removal statute. The Court’s analysis involves two important Supreme Court – Mollan v. Torrance, 22 U.S. 537 (1824), in which Chief Justice Marshall first stated the “time-of-filing” rule (albeit, in a diversity case), and Caterpillar, Inc. v. Lewis, 519 U.S. 61 (19960, a recent treatment of a “cure” of a problem with subject matter jurisdiction. No. 16-60050 (March 30, 2018).

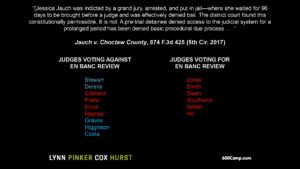

The Fifth Circuit recently denied en banc rehearing in the high-profile qualified immunity case of Jauch v. Choctaw County, where the panel denied immunity to a sheriff who had been sued over a lengthy period of pretrial detention. From one perspective, a chart of the 9-6 vote (below) shows a vote along “party lines,” with all of the votes for rehearing coming from judges appointed by Republican presidents (including both of President Trump’s recent appointments), and with all active judges appointed by Democratic presidents voting against rehearing. From another perspective, the vote shows that the group of active judges appointed by Republican presidents is hardly a monolithic bloc, as it divided roughly in half on the vote.

Midwest Feeders, a cattle feedlot business, sued The Bank of Franklin under Mississippi law, alleging that the Bank tolerated a customer’s fraudulent activities that resulted in considerable financial harm. The Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for the bank. Among other rulings, the Court addressed whether Mississippi law imposed a duty to avoid negligence on a bank, as against a non-customer. Finding no guidance from that state’s supreme court, and inconclusive opinions from other Mississipi courts, the Court surveyed authority nationally and noted “the merits of [the] line of cases” that potentially allowed such liability if the bank knoows of a fiduciary relationship between the customer and the non-customer. Unfortunately for the plaintiff, however, the Court held that “we cannot use our Erie guess to impose upon Mississippi a new regime of liability for its banks.” Midwest Feeders, Inc. v. Bank of Franklin, No. 17-60092 (March 27, 2018).

Midwest Feeders, a cattle feedlot business, sued The Bank of Franklin under Mississippi law, alleging that the Bank tolerated a customer’s fraudulent activities that resulted in considerable financial harm. The Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for the bank. Among other rulings, the Court addressed whether Mississippi law imposed a duty to avoid negligence on a bank, as against a non-customer. Finding no guidance from that state’s supreme court, and inconclusive opinions from other Mississipi courts, the Court surveyed authority nationally and noted “the merits of [the] line of cases” that potentially allowed such liability if the bank knoows of a fiduciary relationship between the customer and the non-customer. Unfortunately for the plaintiff, however, the Court held that “we cannot use our Erie guess to impose upon Mississippi a new regime of liability for its banks.” Midwest Feeders, Inc. v. Bank of Franklin, No. 17-60092 (March 27, 2018).

In Legendre v. Huntington Ingalls, the Fifth Circuit found no “causal nexus” to support removal jurisdiction under the “federal officer” statute. The plaintiff alleged exposure to asbestos fibers brought home on her father’s clothing; he worked in a shipyard in the 1940s building tugs for the U.S. government. Under pre-2011 Fifth Circuit authority, that claim had a problem because the shipyard’s safety practices were not restricted by the government. The statute, however, was amended in 2011 “to allow the removal of a state suit ‘for OR RELATING TO any act under color of such [federa] office.'” Acknowledging that “significant argument,” and noting that other circuits have read the 2011 amendments to eliminate the “causal nexus” requirement, the Court affirmed remand – while plainly inviting a petition for en banc consideration of the issue.No. 17-30371 (March 16, 2018).

In Legendre v. Huntington Ingalls, the Fifth Circuit found no “causal nexus” to support removal jurisdiction under the “federal officer” statute. The plaintiff alleged exposure to asbestos fibers brought home on her father’s clothing; he worked in a shipyard in the 1940s building tugs for the U.S. government. Under pre-2011 Fifth Circuit authority, that claim had a problem because the shipyard’s safety practices were not restricted by the government. The statute, however, was amended in 2011 “to allow the removal of a state suit ‘for OR RELATING TO any act under color of such [federa] office.'” Acknowledging that “significant argument,” and noting that other circuits have read the 2011 amendments to eliminate the “causal nexus” requirement, the Court affirmed remand – while plainly inviting a petition for en banc consideration of the issue.No. 17-30371 (March 16, 2018).

An unusual but intriguing coverage dispute arose after the insured’s death as a result of a bite from a mosquito infected with the dangerous West Nile virus. The Fifth Circuit reversed summary judgment for the carrier, observing in its analysis of the policy’s coverage for “accidental injury” –

An unusual but intriguing coverage dispute arose after the insured’s death as a result of a bite from a mosquito infected with the dangerous West Nile virus. The Fifth Circuit reversed summary judgment for the carrier, observing in its analysis of the policy’s coverage for “accidental injury” –

- The importance of defining the specific injury – “Instead of focusing on Melton’s bite from a WNV-infected Culex mosquito, Minnesota Life argues that a mosquito bite generally is not unexpected and unforeseen in Texas. But a bite by a generic mosquito is not the accidental injury Gloria pleaded in her complaint; instead, she says it is the bite by a WNV-infected Culex mosquito that triggers coverage. Without guidance from the policy as to how broadly or narrowly an ;’accidental bodily injury’ is to be defined, we take the facts of the alleged accidental injury as

Gloria contends.” - And as to whether an injury as “accidental” – the Court quoted then-Judge Cardozo’s analysis from a 1925 opinion about inhalation of an airborne pathogen: “Germs may indeed be inhaled through the nose or mouth, or absorbed into the system through normal channels of entry. In such cases their inroads will seldom, if ever, be assignable to a determinate or single act, identified in space or time. For this as well as for the reason that the absorption is incidental to a bodily process both natural and normal, their action presents itself to the mind as a disease and not an accident.”

- But the Court distinguished the situation addressed by Judge Cardozo: “Here, however, there was a determinate, single act—the bite—that is not incidental to a bodily process. The mosquito, an external “physical” force, affirmatively acted to cause Melton harm and produce an unforeseen result. We find that inhaling a community-spread pathogen and being bitten by a mosquito can be thinly sliced so as to be distinguishable.”

Wells v. Minnesota Life, No. 16-20831 (March 22, 2018).