In Porter v. Times Group, the plaintiff sued People Magazine and two journalists for defamation. The case was removed, and then remanded – one of the individual defendants died and the district court allowed joinder of the Louisiana citizen appointed as that defendant’s “succession representative” under Louisiana law, which destroyed diversity. The Fifth Circuit would not ordinarily have jurisdiction over a remand order because of 28 USC § 1447(d) (“An order remanding a case to the State court from which it was removed is not reviewable on appeal or otherwise . . . .”) People Magazine argued that the joinder decision was reviewable as a collateral order, and the Fifth Circuit disagreed, finding that it did not establish the third and fourth requirements for appeal of such an order (that the order be “effectively unreviewable on an appeal from final judgment” and “too important to be denied review”).

In Porter v. Times Group, the plaintiff sued People Magazine and two journalists for defamation. The case was removed, and then remanded – one of the individual defendants died and the district court allowed joinder of the Louisiana citizen appointed as that defendant’s “succession representative” under Louisiana law, which destroyed diversity. The Fifth Circuit would not ordinarily have jurisdiction over a remand order because of 28 USC § 1447(d) (“An order remanding a case to the State court from which it was removed is not reviewable on appeal or otherwise . . . .”) People Magazine argued that the joinder decision was reviewable as a collateral order, and the Fifth Circuit disagreed, finding that it did not establish the third and fourth requirements for appeal of such an order (that the order be “effectively unreviewable on an appeal from final judgment” and “too important to be denied review”).

The Fifth Circuit made a second discovery-related observation in September, in Norman v. Grove Cranes, a products-liability dispute about a safer alternative design for a crane. The trial judge did not allow the plaintiff’s expert to testify on that point; on appeal, the Fifth Circuit found no abuse of discretion. Plaintiff said the expert “Perkin was unable to form an opinion regarding safer alternative design because Grove failed to produce the documents requested, i.e., the ‘draft design drawings related to the prior design of the crane at issue and similar Grove cranes.’.” The district court disagreed, “pointing out that Norman knew at least 83 days prior to the close of discovery that Perkin needed additional documents to form his expert opinion on safer alternative design but failed to file a motion to compel until a month after the close of discovery,” and noting that the plaintiff’s “failure to seek Court intervention via a motion to compel before the end of discovery shows a lack of diligence in seeking documents [he] now claims are indispensable to his expert’s ability to render a required opinion.” No. 17-20631 (Sept. 10, 2018, unpublished).

The Fifth Circuit made a second discovery-related observation in September, in Norman v. Grove Cranes, a products-liability dispute about a safer alternative design for a crane. The trial judge did not allow the plaintiff’s expert to testify on that point; on appeal, the Fifth Circuit found no abuse of discretion. Plaintiff said the expert “Perkin was unable to form an opinion regarding safer alternative design because Grove failed to produce the documents requested, i.e., the ‘draft design drawings related to the prior design of the crane at issue and similar Grove cranes.’.” The district court disagreed, “pointing out that Norman knew at least 83 days prior to the close of discovery that Perkin needed additional documents to form his expert opinion on safer alternative design but failed to file a motion to compel until a month after the close of discovery,” and noting that the plaintiff’s “failure to seek Court intervention via a motion to compel before the end of discovery shows a lack of diligence in seeking documents [he] now claims are indispensable to his expert’s ability to render a required opinion.” No. 17-20631 (Sept. 10, 2018, unpublished).

The death of the racehorse “Rawhide Canyon” led to hard-fought litigation. The district court denied the plaintiff’s motion to voluntarily dismiss under Fed. R. Civ. P. 41(a)(1), and the Fifth Circuit found an abuse of discretion in not granting it: “Because the payment of attorneys’ fees was the sole basis for the district court’s denial of voluntary dismissal and Plaintiffs subsequently made clear that they would pay these fees, the district court abused its discretion by denying Plaintiffs the ability to voluntarily dismiss their own case.” No. 17-10569 (Sept. 10, 2018, unpublished).

The death of the racehorse “Rawhide Canyon” led to hard-fought litigation. The district court denied the plaintiff’s motion to voluntarily dismiss under Fed. R. Civ. P. 41(a)(1), and the Fifth Circuit found an abuse of discretion in not granting it: “Because the payment of attorneys’ fees was the sole basis for the district court’s denial of voluntary dismissal and Plaintiffs subsequently made clear that they would pay these fees, the district court abused its discretion by denying Plaintiffs the ability to voluntarily dismiss their own case.” No. 17-10569 (Sept. 10, 2018, unpublished).

As neither interlocutory appeals about discovery nor discovery-related mandamus petition produce many Fifth Circuit opinions, a comment about discovery is notable when it is made. In National Urban League v. Urban League of Greater Dallas, as part of a summary judgment appeal, the appellant raised an issue about quashing a 30-b-6 deposition of Edward Smith. The Fifth Circuit found no abuse of discretion in denying a motion to quash when: “Defendant provided no explanation for why Smith could not arrange his travel plans to attend the deposition, given that he had ample notice of it, the funeral was the day before the deposition, and Plaintiff agreed to delay the deposition from the morning until the afternoon to allow for travel. Defendant also did not explain why it waited to object to the Rule 30(b)(6) topics until two days before the deposition was to occur.” No. 17-11469 (Sept. 20, 2018).

As neither interlocutory appeals about discovery nor discovery-related mandamus petition produce many Fifth Circuit opinions, a comment about discovery is notable when it is made. In National Urban League v. Urban League of Greater Dallas, as part of a summary judgment appeal, the appellant raised an issue about quashing a 30-b-6 deposition of Edward Smith. The Fifth Circuit found no abuse of discretion in denying a motion to quash when: “Defendant provided no explanation for why Smith could not arrange his travel plans to attend the deposition, given that he had ample notice of it, the funeral was the day before the deposition, and Plaintiff agreed to delay the deposition from the morning until the afternoon to allow for travel. Defendant also did not explain why it waited to object to the Rule 30(b)(6) topics until two days before the deposition was to occur.” No. 17-11469 (Sept. 20, 2018).

The en banc case of Alvarez v. City of Brownsville involved a difficult question about municipal liability, under 42 U.S.C § 1983, for an alleged Brady violation arising during the plea bargaining process. The plaintiff had won a $2.3 million judgment after a jury trial. The majority opinion found inadequate evidence of deliberate indifference for § 1983 liability; as to the Brady issue, it held that “case law from the Supreme Court, this circuit, and other circuits does

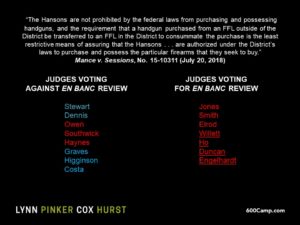

The en banc case of Alvarez v. City of Brownsville involved a difficult question about municipal liability, under 42 U.S.C § 1983, for an alleged Brady violation arising during the plea bargaining process. The plaintiff had won a $2.3 million judgment after a jury trial. The majority opinion found inadequate evidence of deliberate indifference for § 1983 liability; as to the Brady issue, it held that “case law from the Supreme Court, this circuit, and other circuits does  not affirmatively establish that a constitutional violation occurs when Brady material is not shared during the plea bargaining process.” From there, the sixteen judges that comprised this en banc panel authored six other opinions; this chart summarizes the authors and the joinders. No. 16-40772 (Sept. 18, 2018). It is unclear how that breakdown may carry over to commercial cases, but the opinions are revealing insights into a number of judges’ attitudes about structural and constitutional issues.

not affirmatively establish that a constitutional violation occurs when Brady material is not shared during the plea bargaining process.” From there, the sixteen judges that comprised this en banc panel authored six other opinions; this chart summarizes the authors and the joinders. No. 16-40772 (Sept. 18, 2018). It is unclear how that breakdown may carry over to commercial cases, but the opinions are revealing insights into a number of judges’ attitudes about structural and constitutional issues.

This blog celebrates its birthday today; if you want to help celebrate, here’s a recipe for some New Orleans-style beignets.

This blog celebrates its birthday today; if you want to help celebrate, here’s a recipe for some New Orleans-style beignets.

A standard form of an oil-and-gas project’s Joint Operating Agreement contains an attorneys’ fee provision that says: “In the event any party is required to bring legal proceedings to enforce any financial obligation of a party hereunder, the prevailing party in such action shall be entitled to recover . . . a reasonable attorney’s fee.” In Seismic Wells LLC v. Sinclair Oil & Gas Co., the Fifth Circuit found that this provision did not allow fee recovery as to a successful claim about a well damaged by a water leak. “Turning over operatorship rights and running the well on Seismic’s preferred erms are not financial obligations. Sinclair did not refuse to make some payment specified in the agreement.” (emphasis in original). No. 17-10500 (Sept. 13, 2018, unpublished).

A standard form of an oil-and-gas project’s Joint Operating Agreement contains an attorneys’ fee provision that says: “In the event any party is required to bring legal proceedings to enforce any financial obligation of a party hereunder, the prevailing party in such action shall be entitled to recover . . . a reasonable attorney’s fee.” In Seismic Wells LLC v. Sinclair Oil & Gas Co., the Fifth Circuit found that this provision did not allow fee recovery as to a successful claim about a well damaged by a water leak. “Turning over operatorship rights and running the well on Seismic’s preferred erms are not financial obligations. Sinclair did not refuse to make some payment specified in the agreement.” (emphasis in original). No. 17-10500 (Sept. 13, 2018, unpublished).

A recurring issue in litigation about injunctions and similar court orders is how much specificity is required. In In re: Jankovic, a judgment debtor complained about a contempt order requiring his production of tax returns. The specific language required him to:

A recurring issue in litigation about injunctions and similar court orders is how much specificity is required. In In re: Jankovic, a judgment debtor complained about a contempt order requiring his production of tax returns. The specific language required him to:

“. . . do whatever is necessary, including but not limited to correct and proper authorizations, letters to the IRS Commissioner, letters to his Congressmen to help expedite the process, daily calls and visits to the Internal Revenue Services (IRS) headquarters, and anything else that he needs to do, to have the IRS provide to the plaintiffs directly all of the tax returns on file with the IRS for JAI and JAI Holdings from 2010 to the present or, if no tax returns are on file with the IRS, an official statement or documentation from the IRS proving that no tax returns exist for JAI and JAI Holdings for the tax years requested..”

The Fifth Circuit rejected his challenges, noting on this point: “Had the district court simply ordered Jankovic to ‘do whatever is necessary’ to obtain the returns from the IRS, we would have a more difficult question. However, we need not reach that question here because the district court specified particular actions, and Jankovic has not complied with those specific requirements.” No. 18-50720 (Sept. 13, 2018, unpublished).

A retail business sold its defaulted accounts to a debt collector; litigation ensued about the retailer’s warranty in the sales contract that the accounts “have been originated, serviced, and collected in accordance with all applicable laws.” Conn Credit I LP v. TF Loanco III, LLC, No. 17-40148 (Sept. 10, 2018). This requirement created an “unambiguous condition precedent” when contained in a provision stating that the defendant was “obligated to transfer Accounts on a Closing Date only if . . . the representations and warranties of the Buyer or the Seller, respectively, in this Agreement are true and correct as of such Closing Date” (emphasis added). The Fifth Circuit declined to imply a prejudice requirement into the parties’ agreement, noting that “Conn does not identify a single Texas case applying a prejudice requirement outside of the insurance context” involving untimely claim notification.

A retail business sold its defaulted accounts to a debt collector; litigation ensued about the retailer’s warranty in the sales contract that the accounts “have been originated, serviced, and collected in accordance with all applicable laws.” Conn Credit I LP v. TF Loanco III, LLC, No. 17-40148 (Sept. 10, 2018). This requirement created an “unambiguous condition precedent” when contained in a provision stating that the defendant was “obligated to transfer Accounts on a Closing Date only if . . . the representations and warranties of the Buyer or the Seller, respectively, in this Agreement are true and correct as of such Closing Date” (emphasis added). The Fifth Circuit declined to imply a prejudice requirement into the parties’ agreement, noting that “Conn does not identify a single Texas case applying a prejudice requirement outside of the insurance context” involving untimely claim notification.

In Deutsche Bank v. Burke, an appeal after a remand in a mortgage dispute, the magistrate judge “proceeded to defy the mandate and contravene the law of the case doctrine by concluding that our prior opinion was clearly erroneous and that failure to correct the error would result in manifest injustice.” Unsurprisingly, the Fifth Circuit reversed, reviewing the basic principles about those doctrines, and observing that “the conduct here is extraordinary conduct that would lead to chaos if routinely done.” No. 18-20026 (Sept. 5, 2018).

In Deutsche Bank v. Burke, an appeal after a remand in a mortgage dispute, the magistrate judge “proceeded to defy the mandate and contravene the law of the case doctrine by concluding that our prior opinion was clearly erroneous and that failure to correct the error would result in manifest injustice.” Unsurprisingly, the Fifth Circuit reversed, reviewing the basic principles about those doctrines, and observing that “the conduct here is extraordinary conduct that would lead to chaos if routinely done.” No. 18-20026 (Sept. 5, 2018).

After a thorough review of the “fundamental relationship between a relator and the Government in qui tam actions,” the Fifth Circuit concluded that private relators dismissal of an action with prejudice did not bind the non-intervening U.S. government: “[R]elators sought to abandon their claims because they no longer wished to participate in the litigation. In other words, they acted on purely private interests. The Government—even one that chooses not to intervene—should not be bound by this decision, powerless to vindicate the public’s interests in other actions that may have a stronger basis or a relator more able to shoulder the burdens of litigation.” U.S. ex rel. Vaughn v. United Biologics LLC, No. 17-20389 (Sept. 7, 2018).

After a thorough review of the “fundamental relationship between a relator and the Government in qui tam actions,” the Fifth Circuit concluded that private relators dismissal of an action with prejudice did not bind the non-intervening U.S. government: “[R]elators sought to abandon their claims because they no longer wished to participate in the litigation. In other words, they acted on purely private interests. The Government—even one that chooses not to intervene—should not be bound by this decision, powerless to vindicate the public’s interests in other actions that may have a stronger basis or a relator more able to shoulder the burdens of litigation.” U.S. ex rel. Vaughn v. United Biologics LLC, No. 17-20389 (Sept. 7, 2018).

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau – the subject of ongoing litigation about the constitutionality of its structure, which has been at issue in the recent Kavanaugh hearings – lost a challenge to a civil investigative demand in CFPB v. The Source for Public Data: “The CFPB did not comply with 12 U.S.C. § 5562(c)(2) when it issued this CID to Public Data. First, it did not state the ‘conduct constituting the alleged violation which is under investigation.’ According to its Notification of Purpose, the CFPB is investigating ‘unlawful acts and practices in connection with the provision or use of public records information.’ Simply put, this Notification of Purpose does not identify what conduct, it believes, constitutes an alleged violation. . . . Moreover, this CID does not identify ‘the provision of law applicable to such violation.’ As discussed, the CID never identifies an alleged violation, so it is unsurprising that it fails to identify a relevant provision of law.” No. 17-10732 (Sept. 6, 2018).

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau – the subject of ongoing litigation about the constitutionality of its structure, which has been at issue in the recent Kavanaugh hearings – lost a challenge to a civil investigative demand in CFPB v. The Source for Public Data: “The CFPB did not comply with 12 U.S.C. § 5562(c)(2) when it issued this CID to Public Data. First, it did not state the ‘conduct constituting the alleged violation which is under investigation.’ According to its Notification of Purpose, the CFPB is investigating ‘unlawful acts and practices in connection with the provision or use of public records information.’ Simply put, this Notification of Purpose does not identify what conduct, it believes, constitutes an alleged violation. . . . Moreover, this CID does not identify ‘the provision of law applicable to such violation.’ As discussed, the CID never identifies an alleged violation, so it is unsurprising that it fails to identify a relevant provision of law.” No. 17-10732 (Sept. 6, 2018).

In 2018, the Texas Supreme Court and the Fifth Circuit have taken different approaches to an important type of “Casteel” problem, in which a jury question has several legally viable theories, some of which are not supported with adequate evidence.

In 2018, the Texas Supreme Court and the Fifth Circuit have taken different approaches to an important type of “Casteel” problem, in which a jury question has several legally viable theories, some of which are not supported with adequate evidence.

Federal. After a thorough (and infrequently-seen) summary of how federal law has developed on the “Casteel problem” of commingled liability theories, the Fifth Circuit concluded in Nester v. Textron, Inc., 888 F.3d 151 (5th Cir. 2018): “We will not reverse a verdict simply because the jury might have decided on a ground that was supported by insufficient evidence.” (applying, inter alia, Griffin v. United States, 502 U.S. 46 (1991)).

State. In Benge v. Williams, 548 S.W.3d 466 (Tex. 2018), a medical-malpractice case, the Texas Supreme Court observed: “The jury question in the present case, unlike the one in Casteel, did not include multiple theories, some valid and some invalid. It inquired about a single theory: negligence. But we have twice held that when the question allows a finding of liability based on evidence that cannot support recovery, the same presumption-of-harm rule must be applied.”

(Thanks to Mark Trachtenberg for pointing out this comparison at the recent Advanced Civil Appellate Course!)

The plaintiff in Bloom v. Aftermath Public Adjusters, Inc. tried to overcome a limitations problem with the tolling doctrine for malpractice claims recognized by Hughes v. Mahaney & Higgins, 821 S.W.2d 154 (Tex. 1991). The plaintiff’s claim involved the conduct of a licensed public adjuster working for an insurance company; the Ffith Circuit characterized his argument as saying “that public adjusters are actually lawyers in disguise. Bloom concedes defendants are technically ‘non-lawyers,’ but he insists they effectively ‘provide[d] legal services,’ because there was once a time when Texas prohibited non-lawyers from engaging in public adjusting.” The Court was unpersuaded in this Erie case:

The plaintiff in Bloom v. Aftermath Public Adjusters, Inc. tried to overcome a limitations problem with the tolling doctrine for malpractice claims recognized by Hughes v. Mahaney & Higgins, 821 S.W.2d 154 (Tex. 1991). The plaintiff’s claim involved the conduct of a licensed public adjuster working for an insurance company; the Ffith Circuit characterized his argument as saying “that public adjusters are actually lawyers in disguise. Bloom concedes defendants are technically ‘non-lawyers,’ but he insists they effectively ‘provide[d] legal services,’ because there was once a time when Texas prohibited non-lawyers from engaging in public adjusting.” The Court was unpersuaded in this Erie case:

“But that was then, and this is now. Even assuming Texas law previously classified public adjusting as legal practice, under the relevant regime, these defendants are non-lawyers who were not engaged in legal practice. By definition, Bloom’s claims cannot implicate the unique relationship that triggers the bright-line rule from Hughes. Only Texas has the power to say where lawyer-ing ends and adjusting begins, just as its courts have the sole power to decide Hughes’s outer bounds.”

No. 17-41087 (Sept. 4, 2018).

I commented today about the start of the Kavanaugh hearings on the morning show of Dallas’s Fox affiliate.

I commented today about the start of the Kavanaugh hearings on the morning show of Dallas’s Fox affiliate.

Having just now seen Darkest Hour, the Academy Award-winning film about Churchill confronting Britain’s terrible military situation in May of 1940, I was inspired to update this blog’s page about legal writing with an essay written by Churchill as a young man called “The Scaffolding of Rhetoric.” It illustrates five simple ways to put words together to add power to the overall message they convey.

Having just now seen Darkest Hour, the Academy Award-winning film about Churchill confronting Britain’s terrible military situation in May of 1940, I was inspired to update this blog’s page about legal writing with an essay written by Churchill as a young man called “The Scaffolding of Rhetoric.” It illustrates five simple ways to put words together to add power to the overall message they convey.

The plaintiffs in Alaska Elec. Pension Fund v. Asar alleged securities fraud about the affairs of Hanger, Inc., the nation’s largest provider of orthotic and prosthetic patient care. The Fifth Circuit largely affirmed dismissal, but as to one defendant found adequate allegations of scienter based primarily on statements in an audit committee report, which “support the inference that McHenry shared the objectives of improperly enhancing Hanger’s financial results, or that he at least knew that others were doing so. A dissent would have also dismissed as to him, noting that “the complaint makes no effort to demonstrate which portions of the Report show that McHenry, or any other defendant, had the requisite scienter.” No. 17-50162 (Aug. 6, 2018).

The plaintiffs in Alaska Elec. Pension Fund v. Asar alleged securities fraud about the affairs of Hanger, Inc., the nation’s largest provider of orthotic and prosthetic patient care. The Fifth Circuit largely affirmed dismissal, but as to one defendant found adequate allegations of scienter based primarily on statements in an audit committee report, which “support the inference that McHenry shared the objectives of improperly enhancing Hanger’s financial results, or that he at least knew that others were doing so. A dissent would have also dismissed as to him, noting that “the complaint makes no effort to demonstrate which portions of the Report show that McHenry, or any other defendant, had the requisite scienter.” No. 17-50162 (Aug. 6, 2018).

While cleaning ventilation equipment at the L’Auberge Casino in Lake Charles, Renwick fell from a defective ladder and later sued the property owner for his injuries. The Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment for the defense, noting “that it is th[e] combination of evidence–[Defendant’s] control of work-site access, its specific instructions about how to reach the vents, its rejection of an alternate access route, and the dispute over who provided the access ladder–that creates a jury issue on operational control.” (emphasis in original0 The Court reminded: “To be sure, a fact finder could ultimately reach a different conclusion. All we decide is that the evidence –viewed, as it must be, in the light most favorable to Renwick– would permit a reasonable trier of fact to resolve the operational control issue either way, and that the district court therefore erred in granting summary judgment.” Renwick v. PNK Lake Charles LLC, No. 17-30767 (Aug. 27, 2018).

While cleaning ventilation equipment at the L’Auberge Casino in Lake Charles, Renwick fell from a defective ladder and later sued the property owner for his injuries. The Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment for the defense, noting “that it is th[e] combination of evidence–[Defendant’s] control of work-site access, its specific instructions about how to reach the vents, its rejection of an alternate access route, and the dispute over who provided the access ladder–that creates a jury issue on operational control.” (emphasis in original0 The Court reminded: “To be sure, a fact finder could ultimately reach a different conclusion. All we decide is that the evidence –viewed, as it must be, in the light most favorable to Renwick– would permit a reasonable trier of fact to resolve the operational control issue either way, and that the district court therefore erred in granting summary judgment.” Renwick v. PNK Lake Charles LLC, No. 17-30767 (Aug. 27, 2018).

OGA Charters entered bankruptcy after a tragic accident involving one of its buses. Applying Louisiana World Exposition Inc. v. Fed. Ins. Co., 832 F.2d 1391 (5th Cir. 1987), and Houston v. Edgeworth, 993 F.2d 51 (5th Cir. 1993), the Fifth Circuit held: “We now make official what our cases have long contemplated: In the ‘limited circumstances,’ as here, where a siege of tort claimants threaten the debtor’s estate over and above the policy limits, we classify the proceeds as property of the estate. Here, over $400 million in related claims threaten the debtor’s estate over and above the $5 million policy limit, giving rise to an equitable interest of the debtor in having the proceeds applied to satisfy as much of those claims as possible.” Martinez v. OGA Charters LLC, No. 17-40920 (Aug. 24, 2018).

Monty Python’s famous “Dead Parrot” sketch involved John Cleese and Michael Palin debating whether a dead bird sold by a pet store was, in fact, deceased. In that same spirit, the case of Alliance for Good Government v. Coalition for Better Government addressed whether the Coalition’s bird-based logo infringed the Alliance’s logo:

Monty Python’s famous “Dead Parrot” sketch involved John Cleese and Michael Palin debating whether a dead bird sold by a pet store was, in fact, deceased. In that same spirit, the case of Alliance for Good Government v. Coalition for Better Government addressed whether the Coalition’s bird-based logo infringed the Alliance’s logo:

Alliance won in the trial court, as the birds appear identical, “with the same down-point ed beak, gazing over the same wing (the right), sporting the same number of feathers (forty-three).” Unphased, Coalition argued that its bird was a hawk, while Alliance’s was an eagle, leading to a puzzled exchange with the district judge:

ed beak, gazing over the same wing (the right), sporting the same number of feathers (forty-three).” Unphased, Coalition argued that its bird was a hawk, while Alliance’s was an eagle, leading to a puzzled exchange with the district judge:

DISTRICT COURT: They look exactly alike to me, the two birds.

COUNSEL: […] [N]o, they really aren’t, your Honor, if you look at the wing span. The wing span of the eagle is different from the hawk. It’s much larger and it fans out, and that’s just the way the hawk looks.

Equally puzzled, the Fifth Circuit affirmed: “To cut to the chase: Alliance and Coalition have the same logo.” No. 17-30859 (Aug. 22, 2018) (emphasis in original).

IAS, an insurance claim-adjusting firm, acquired Buckley, another such firm. Litigation ensued after Buckley was unable to bring the business from a large client, QBE. The Fifth Circuit found that IAS stated a viable fraudulent-inducement claim under Fed. R. Civ. P. 9(b) as to “three alleged misrepresentations that it contends led it to enter into the asset purchase agreement: (1) Buckley’s statement that Buckley & Associates was QBE’s ‘number one’ vendor; (2) Buckley’s statement that Buckley & Associates’ revenue from QBE would continue to grow; and (3) the statement in § 2.3 of the purchase agreement that its execution would not ‘violate, conflict, [or] result in a breach of . . . any Contract . . . to which [Buckley & Associates] is a party.'” The Court’s analysis of the third factor is particularly informative, touching on recent Texas Supreme Court authority about waiver-of-reliance provisions (Italian Cowboy Partners v. Prudential Ins. Co., 341 S.W.3d 323 (Tex. 2011)) and “red flags” that can negate justifiable reliance. (JPMorgan Chase Bank v. Orca Assets GP, LLC, 546 S.W.3d 648 (Tex. 2018)). A dissent would not have found any of the representations fraudulent as pleaded. IAS Service Group v. Buckley & Assocs., No. 17-50105 (Aug. 17, 2018).

IAS, an insurance claim-adjusting firm, acquired Buckley, another such firm. Litigation ensued after Buckley was unable to bring the business from a large client, QBE. The Fifth Circuit found that IAS stated a viable fraudulent-inducement claim under Fed. R. Civ. P. 9(b) as to “three alleged misrepresentations that it contends led it to enter into the asset purchase agreement: (1) Buckley’s statement that Buckley & Associates was QBE’s ‘number one’ vendor; (2) Buckley’s statement that Buckley & Associates’ revenue from QBE would continue to grow; and (3) the statement in § 2.3 of the purchase agreement that its execution would not ‘violate, conflict, [or] result in a breach of . . . any Contract . . . to which [Buckley & Associates] is a party.'” The Court’s analysis of the third factor is particularly informative, touching on recent Texas Supreme Court authority about waiver-of-reliance provisions (Italian Cowboy Partners v. Prudential Ins. Co., 341 S.W.3d 323 (Tex. 2011)) and “red flags” that can negate justifiable reliance. (JPMorgan Chase Bank v. Orca Assets GP, LLC, 546 S.W.3d 648 (Tex. 2018)). A dissent would not have found any of the representations fraudulent as pleaded. IAS Service Group v. Buckley & Assocs., No. 17-50105 (Aug. 17, 2018).

The hard-fought litigation over Harris County’s bail policies returned to the Fifth Circuit after a limited remand on the scope and structure of proper injunctive relief. The Court granted a stay pending resolution of the merits; in particular, noting the effect of the appellate “mandate rule” on 3 parts of the revised injunction:

The hard-fought litigation over Harris County’s bail policies returned to the Fifth Circuit after a limited remand on the scope and structure of proper injunctive relief. The Court granted a stay pending resolution of the merits; in particular, noting the effect of the appellate “mandate rule” on 3 parts of the revised injunction:

- “The original injunction contained the requirement that a hearing be held within 24 hours. Thus, the same issue of what to do with arrestees during the gap between arrest and hearing—be it 24 or 48 hours—was always at issue and could have been addressed during the initial proceedings. Remand is not the time to bring new issues that could have been raised initially. Thus, Section 7 plainly violates the mandate rule, and the Fourteen Judges are likely to succeed on the merits as to that section.” (emphasis added)

- “[The first appeal determined that 48 hours was sufficient under the Constitution.. . . [I]n the model injunction, the proposed remedy for failure to comply with that requirement was for the County to make weekly reports to the district court identifying any delays and to inform the detainees’ counsel or next of kin about the delays. . . . The district co

urt was to monitor the situation for a pattern of violations and only then take possible corrective action. Anything broader than that remedy violates any reasonable reading of the mandate.” (emphasis added).

urt was to monitor the situation for a pattern of violations and only then take possible corrective action. Anything broader than that remedy violates any reasonable reading of the mandate.” (emphasis added).

O’Donnell v. Goodhart, No. 18-20466 (Aug. 14, 2018).

At the intersection of civil and criminal law, United States v. Gas Pipe reminds of the reach of the federal civil forfeiture: “Although ‘merely pooling tainted and untainted funds in an account does not, without more, render that account subject to forfeiture,’ untainted funds are forfeitable if a defendant commingled them with tainted funds ‘to disguise the nature and source of his scheme.’ Here, the Government alleged in its verified complaint that the defendant Claimants commingled tainted and untainted funds in the UBS accounts to conceal or disguise the tainted funds. Some commingled funds allegedly also secured a loan that financed the alleged spice scheme and which was repaid with criminal proceeds.” No. 17-10626 (Aug. 16, 2018) (citations omitted).

At the intersection of civil and criminal law, United States v. Gas Pipe reminds of the reach of the federal civil forfeiture: “Although ‘merely pooling tainted and untainted funds in an account does not, without more, render that account subject to forfeiture,’ untainted funds are forfeitable if a defendant commingled them with tainted funds ‘to disguise the nature and source of his scheme.’ Here, the Government alleged in its verified complaint that the defendant Claimants commingled tainted and untainted funds in the UBS accounts to conceal or disguise the tainted funds. Some commingled funds allegedly also secured a loan that financed the alleged spice scheme and which was repaid with criminal proceeds.” No. 17-10626 (Aug. 16, 2018) (citations omitted).

Veritext, a national court reporting service, challenged restrictions on its pricing practices (volume discounts, etc.) imposed by the Louisiana Board of Examiners of Certified Shorthand Reporters. The Fifth Circuit rejected Veritext’s constitutional claims but found that it had stated a viable restraint-of-trade claim under the Sherman Act. The Board claimed Parker antitrust immunity as a state actor, which required it to show “two requirements: first that ‘the challenged restraint . . . be one clearly articulated and affirmatively expressed as state policy,’ and second that ‘the policy . . . be actively supervised by the State.’” The Board satisfied the first, as its regulations were clear (thus creating the alleged restraint of trade in the first

Veritext, a national court reporting service, challenged restrictions on its pricing practices (volume discounts, etc.) imposed by the Louisiana Board of Examiners of Certified Shorthand Reporters. The Fifth Circuit rejected Veritext’s constitutional claims but found that it had stated a viable restraint-of-trade claim under the Sherman Act. The Board claimed Parker antitrust immunity as a state actor, which required it to show “two requirements: first that ‘the challenged restraint . . . be one clearly articulated and affirmatively expressed as state policy,’ and second that ‘the policy . . . be actively supervised by the State.’” The Board satisfied the first, as its regulations were clear (thus creating the alleged restraint of trade in the first  place), but failed the second: “Nothing in the record indicates that elected or appointed officials oversaw or reviewed the Board’s decisions or modified the Board’s enforcement priorities. And the Board’s argument on this point—that the legislature can amend the law in this area or veto proposed rules under Louisiana’s Administrative Procedure Act—is unconvincing. State legislatures always possess the power to change the law.” Veritext Corp. v. Bonin, No. 17-30691 (Aug. 17, 2018) (applying State Board of Dental Examiners v. FTC, 135 S.Ct. 1101 (2015)).

place), but failed the second: “Nothing in the record indicates that elected or appointed officials oversaw or reviewed the Board’s decisions or modified the Board’s enforcement priorities. And the Board’s argument on this point—that the legislature can amend the law in this area or veto proposed rules under Louisiana’s Administrative Procedure Act—is unconvincing. State legislatures always possess the power to change the law.” Veritext Corp. v. Bonin, No. 17-30691 (Aug. 17, 2018) (applying State Board of Dental Examiners v. FTC, 135 S.Ct. 1101 (2015)).

Fou r of my LPCH partners and I were recently named to “Best Lawyers in America” for 2019!

r of my LPCH partners and I were recently named to “Best Lawyers in America” for 2019!

An expert’s analysis of an electrical fire on a boat involved a “‘hose test,’ in which he directed water from a garden hose onto the boat’s wet bar and tracked where the water ended up.” Unfortunately for him, because this work was “meant to be a simulation or re-creation of what actually happened, it must be performed under ‘substantially similar conditions'” to the fire, and it was not: “Plaisance’s videos did not contain important information about how he conducted the experiment, such as ‘how long the hose ha[d] been running’ or ‘the pressure of the water coming out of the hose.’ Moreover, the video showed ‘a continuous stream of water from a garden hose directly at the junction between the back of the wet bar and the boat’s wall,’ and there was no indication that Gonzalez ever used a hose in that fashion. In fact, as the district court noted, Plaisance did not provide any information about how Gonzalez typically washed the boat.” Similar problems also undermined another expert’s testimony about electrical issues on the boat. Atlantic Specialty Insurance Co. v. Porter, Inc., No. 16-31259 (Aug. 6, 2018).

An expert’s analysis of an electrical fire on a boat involved a “‘hose test,’ in which he directed water from a garden hose onto the boat’s wet bar and tracked where the water ended up.” Unfortunately for him, because this work was “meant to be a simulation or re-creation of what actually happened, it must be performed under ‘substantially similar conditions'” to the fire, and it was not: “Plaisance’s videos did not contain important information about how he conducted the experiment, such as ‘how long the hose ha[d] been running’ or ‘the pressure of the water coming out of the hose.’ Moreover, the video showed ‘a continuous stream of water from a garden hose directly at the junction between the back of the wet bar and the boat’s wall,’ and there was no indication that Gonzalez ever used a hose in that fashion. In fact, as the district court noted, Plaisance did not provide any information about how Gonzalez typically washed the boat.” Similar problems also undermined another expert’s testimony about electrical issues on the boat. Atlantic Specialty Insurance Co. v. Porter, Inc., No. 16-31259 (Aug. 6, 2018).

Federal crop insurance “protects an asset that does not yet exist,” since future crops are not yet grown. Congress refined the applicable statutes in 2014, allowing farmers to “elect to exclude” certain low-production

Federal crop insurance “protects an asset that does not yet exist,” since future crops are not yet grown. Congress refined the applicable statutes in 2014, allowing farmers to “elect to exclude” certain low-production  years from the historical calculations needed to write insurance for future crop production. The relevant amendment applied “for any of the 2001 and subsequent crop years,” and became effective immediately. A dispute arose between Texas winter wheat farmers, who announced their intention to exclude years under this statute, and the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation, who said it lacked time to prepare the necessary data. The Fifth Circuit rejected the FCIC’s argument that this statute’s “effective” date was distinct from its “implementation” date, finding that it failed step one of Chevron – “Such a problem arises not from an ambiguous

years from the historical calculations needed to write insurance for future crop production. The relevant amendment applied “for any of the 2001 and subsequent crop years,” and became effective immediately. A dispute arose between Texas winter wheat farmers, who announced their intention to exclude years under this statute, and the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation, who said it lacked time to prepare the necessary data. The Fifth Circuit rejected the FCIC’s argument that this statute’s “effective” date was distinct from its “implementation” date, finding that it failed step one of Chevron – “Such a problem arises not from an ambiguous  text but from Congress implementing razor sharp deadlines without, at least according to the FCIC, sufficient resources. That does not give the FCIC authority to disregard the plain text of the statute . . . .” Adkins v. Silverman, No. 17-10759 (Aug. 7, 2018).

text but from Congress implementing razor sharp deadlines without, at least according to the FCIC, sufficient resources. That does not give the FCIC authority to disregard the plain text of the statute . . . .” Adkins v. Silverman, No. 17-10759 (Aug. 7, 2018).

The parties settled and filed an unconditional stipulation of dismissal under Fed. R Civ. P. 41(a)(1)(A)(ii). Months later, one of them sought to reopen that action and rescind the settlement, alleging forgery of a key signature. The Fifth Circuit found that “ancillary jurisdiction” was not available, as that doctrine is limited to (1) “factually interdependent claims” (which “disappear[] . . . after the original federal dispute is dismissed,” or (2) “‘collateral issues’ . . . things like fees, costs, contempt, and sanctions,” which could apply to an appropriate order but not to this type of unconditional dismissal. The Court found jurisdiction under Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(1), which addresses “mistake, inadvertence, surprise, or excusable neglect,” but was of little help here where the settlement documents expressly allocated risk about later-discovered evidence. Other parts of that rule did not apply. “By unconditionally dismissing this action under Rule 41(a)(1)(A)(ii), the parties divested the district court of subject-matter jurisdiction over their dispute. To reopen this case, Scott must lean on Rule 60(b). But that rule’s six doors remain closed.” National City Golf Finance v. Scott, No. 17-60283 (Aug. 9, 2018).

The parties settled and filed an unconditional stipulation of dismissal under Fed. R Civ. P. 41(a)(1)(A)(ii). Months later, one of them sought to reopen that action and rescind the settlement, alleging forgery of a key signature. The Fifth Circuit found that “ancillary jurisdiction” was not available, as that doctrine is limited to (1) “factually interdependent claims” (which “disappear[] . . . after the original federal dispute is dismissed,” or (2) “‘collateral issues’ . . . things like fees, costs, contempt, and sanctions,” which could apply to an appropriate order but not to this type of unconditional dismissal. The Court found jurisdiction under Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(1), which addresses “mistake, inadvertence, surprise, or excusable neglect,” but was of little help here where the settlement documents expressly allocated risk about later-discovered evidence. Other parts of that rule did not apply. “By unconditionally dismissing this action under Rule 41(a)(1)(A)(ii), the parties divested the district court of subject-matter jurisdiction over their dispute. To reopen this case, Scott must lean on Rule 60(b). But that rule’s six doors remain closed.” National City Golf Finance v. Scott, No. 17-60283 (Aug. 9, 2018).

Problems in the construction of the Zapata County courthouse (right) led to litigation between S&P (the general contractor), and its subcontractors, as well as between S&P and its insurer. The insurer and S&P disputed S&P’s allocation of the proceeds from settlements with the subcontractors, and the Fifth Circuit affirmed judgment for the insurer: “S&P bears the burden to show that the subcontractor settlement proceeds were properly allocated to either covered or noncovered damages. If S&P cannot meet that burden, under the [two controlling cases], then we must assume that all of the settlement proceeds went first to satisfy the covered damages under U.S. Fire’s policy.” Satterfield & Pontikes Constr. v. U.S. Fire Ins. Co., No. 17-20513 (Aug. 2, 2018).

Problems in the construction of the Zapata County courthouse (right) led to litigation between S&P (the general contractor), and its subcontractors, as well as between S&P and its insurer. The insurer and S&P disputed S&P’s allocation of the proceeds from settlements with the subcontractors, and the Fifth Circuit affirmed judgment for the insurer: “S&P bears the burden to show that the subcontractor settlement proceeds were properly allocated to either covered or noncovered damages. If S&P cannot meet that burden, under the [two controlling cases], then we must assume that all of the settlement proceeds went first to satisfy the covered damages under U.S. Fire’s policy.” Satterfield & Pontikes Constr. v. U.S. Fire Ins. Co., No. 17-20513 (Aug. 2, 2018).

The district court dismissed fraud claims against an accounting firm for not complying with a Louisiana pre-suit review requirement. The Fifth Circuit affirmed but remanded for clarification as to whether the dismissal was with, or without, prejudice. Fed. R. Civ. P. 41 generally assumes that silence means “with

The district court dismissed fraud claims against an accounting firm for not complying with a Louisiana pre-suit review requirement. The Fifth Circuit affirmed but remanded for clarification as to whether the dismissal was with, or without, prejudice. Fed. R. Civ. P. 41 generally assumes that silence means “with  prejudice,” but the Supreme Court has recognized that that rule’s exception for “jurisdiction” goes so far as “encompassing those dismissals which are based on a plaintiff’s failure to comply with a precondition requisite to the Court’s going forward to determine the merits of his substantive claim.”

prejudice,” but the Supreme Court has recognized that that rule’s exception for “jurisdiction” goes so far as “encompassing those dismissals which are based on a plaintiff’s failure to comply with a precondition requisite to the Court’s going forward to determine the merits of his substantive claim.”

Firefighters’ Retirement System v. EisenerAmper LLP, No. 17-30273 (Aug. 2, 2018).

“Aetna’s reliance on any alleged misrepresentation by NCMC was not justifiable. Almost immediately after NCMC notified Aetna of its prompt pay discount, Aetna began investigating. Its investigation revealed NCMC’s billing practices. Yet Aetna continued to pay claims marked with the prompt pay discount moniker.” In support, the Fifth Circuit cited the recent and influential case of JPMorgan Chase v. Orca Assets, 546 S.W.3d 648 (Tex. 2018), and “promoted” the unpublished case of Highland Crusader Offshore Partners v. LifeCare Holdings, 377 F. App’x 422 (5th Cir. 2010), observing: “The panel recognizes that Highland Crusader is unpublished, and therefore not precedential, but we cite it here to show consistency throughout our case law.” North Cypress Medical Center v. Aetna, No. 16-20674 (July 31, 2018).

“Aetna’s reliance on any alleged misrepresentation by NCMC was not justifiable. Almost immediately after NCMC notified Aetna of its prompt pay discount, Aetna began investigating. Its investigation revealed NCMC’s billing practices. Yet Aetna continued to pay claims marked with the prompt pay discount moniker.” In support, the Fifth Circuit cited the recent and influential case of JPMorgan Chase v. Orca Assets, 546 S.W.3d 648 (Tex. 2018), and “promoted” the unpublished case of Highland Crusader Offshore Partners v. LifeCare Holdings, 377 F. App’x 422 (5th Cir. 2010), observing: “The panel recognizes that Highland Crusader is unpublished, and therefore not precedential, but we cite it here to show consistency throughout our case law.” North Cypress Medical Center v. Aetna, No. 16-20674 (July 31, 2018).

John Williams was seriously injured in a  crane accident; a jury found that the crane manufacturer “failed to warn Model 16000 Series crane operators that, if the crane tips over, large weights stacked on the rear of the crane can slide forward and strike the operator’s cab.” The Fifth Circuit affirmed that multi-million dollar verdict, finding that the jury acted within its authority as to (1) liability for failure to warn, (2) proximate cause and alleged misuse by Williams, (3) proximate cause and an alleged alternative warning (left),

crane accident; a jury found that the crane manufacturer “failed to warn Model 16000 Series crane operators that, if the crane tips over, large weights stacked on the rear of the crane can slide forward and strike the operator’s cab.” The Fifth Circuit affirmed that multi-million dollar verdict, finding that the jury acted within its authority as to (1) liability for failure to warn, (2) proximate cause and alleged misuse by Williams, (3) proximate cause and an alleged alternative warning (left), (4) a Daubert challenge to the plaintiff’s expert on warnings (applying Roman v. Western Manufacturing, 691 F.3d 686 (5th Cir. 2012), and Huss v. Gayden, 571 F.3d 443 (5th Cir. 2009) – two powerful statements by the Court about admissible expert analysis), and (5) admissibility rulings about other accidents and the plaintiff’s prior conduct. The opinion provides a powerful illustration of a well-conducted trial by jury. Williamv v. Manitowoc Cranes LLC, No. 17-60458 (Aug. 3, 2018).

(4) a Daubert challenge to the plaintiff’s expert on warnings (applying Roman v. Western Manufacturing, 691 F.3d 686 (5th Cir. 2012), and Huss v. Gayden, 571 F.3d 443 (5th Cir. 2009) – two powerful statements by the Court about admissible expert analysis), and (5) admissibility rulings about other accidents and the plaintiff’s prior conduct. The opinion provides a powerful illustration of a well-conducted trial by jury. Williamv v. Manitowoc Cranes LLC, No. 17-60458 (Aug. 3, 2018).

Villareal sought to redeem five certificates of deposit purchased in the early 1980s. His primary legal theory, apparently selected to avoid problems with suing on the instruments themselves, was the quasi-contractual / restitution theory recognized in Texas law for “money had and received.” That theory ordinarily does not apply when an express contract (here, the CDs) addresses the subject. To escape that limitation, Villareal relied on Texas authority under which “an overpayment beyond what a contract provides may sometimes be recovered as unjust enrichment. If an overpayment qualifies as unjust enrichment, reasoned the district court, so should an underpayment.” (citation omitted, emphasis in original). The Fifth Circuit disagreed: “Overpayment typically falls outside a contract’s terms and, in that event, the contract would not ‘cover[] the subject matter of the parties’ dispute.’ By contrast, here the dispute involved the claimed non-payment of a debt evidenced by express contracts (the CDs). Unjust enrichment has no role to play.” (citation omitted, emphasis in original). Villareal v. Presidio Nat’l Bank (revised), No. 17-50765 (July 27, 2018, unpublished). (Picture above of Professor Samuel Williston eyeing some of his extensive work on express contracts).

Villareal sought to redeem five certificates of deposit purchased in the early 1980s. His primary legal theory, apparently selected to avoid problems with suing on the instruments themselves, was the quasi-contractual / restitution theory recognized in Texas law for “money had and received.” That theory ordinarily does not apply when an express contract (here, the CDs) addresses the subject. To escape that limitation, Villareal relied on Texas authority under which “an overpayment beyond what a contract provides may sometimes be recovered as unjust enrichment. If an overpayment qualifies as unjust enrichment, reasoned the district court, so should an underpayment.” (citation omitted, emphasis in original). The Fifth Circuit disagreed: “Overpayment typically falls outside a contract’s terms and, in that event, the contract would not ‘cover[] the subject matter of the parties’ dispute.’ By contrast, here the dispute involved the claimed non-payment of a debt evidenced by express contracts (the CDs). Unjust enrichment has no role to play.” (citation omitted, emphasis in original). Villareal v. Presidio Nat’l Bank (revised), No. 17-50765 (July 27, 2018, unpublished). (Picture above of Professor Samuel Williston eyeing some of his extensive work on express contracts).

After trial of a Lanham Act claim involving the right to use the term “Cowboy” in advertising bourbon, the jury found abandonment of the plaintiff’s alleged mark, and the Fifth Circuit affirmed. “As the district court observed, the jury fairly rejected the testimony of Allied’s founder, Marci Palatella, and Allied’s price lists as evidence of intent to resume use. . . . Garrison Brothers presented evidence undermining Palatella’s contention that Allied specializes in old, rare, and expensive whiskeys; disputing Palatella’s reliance on a bourbon shortage as a reason for Allied’s failure to sell ‘COWBOY LITTLE BARREL’ bourbon after 2009; and highlighting Palatella’s inconsistent testimony concerning Allied’s price lists.” Allied Lomar, Inc. v. Lone Star Distillery LLC, No. 17-50148 (July 17, 2018, unpublished).

After trial of a Lanham Act claim involving the right to use the term “Cowboy” in advertising bourbon, the jury found abandonment of the plaintiff’s alleged mark, and the Fifth Circuit affirmed. “As the district court observed, the jury fairly rejected the testimony of Allied’s founder, Marci Palatella, and Allied’s price lists as evidence of intent to resume use. . . . Garrison Brothers presented evidence undermining Palatella’s contention that Allied specializes in old, rare, and expensive whiskeys; disputing Palatella’s reliance on a bourbon shortage as a reason for Allied’s failure to sell ‘COWBOY LITTLE BARREL’ bourbon after 2009; and highlighting Palatella’s inconsistent testimony concerning Allied’s price lists.” Allied Lomar, Inc. v. Lone Star Distillery LLC, No. 17-50148 (July 17, 2018, unpublished).

In addition to inspiring 600Camp’s most painful pun of 2018, Ditech Financial LLC v. Naumann provides a thorough summary of the requirement – unique to default judgments, among all judgments available under the Federal Rules – that the relief awarded “must not differ in kind from, or exceed in amount, what is demanded in the pleadings.” As applied here, “Ditech’s demand for judicial foreclosure gave meaningful notice that, in the event of default, a writ of possession would issue in favor of the foreclosure-sale purchaser. Texas’s process of enforcing a judicial foreclosure—and specifically its mechanism for enforcing the foreclosure sale— entails issuance of the writ. Accordingly, in this case the judgment’s provision for future issuance of the writ did not expand or alter the kind or amount of relief prayed for by Ditech.” No. 17-50616 (July 19, 2018, unpublished).

In addition to inspiring 600Camp’s most painful pun of 2018, Ditech Financial LLC v. Naumann provides a thorough summary of the requirement – unique to default judgments, among all judgments available under the Federal Rules – that the relief awarded “must not differ in kind from, or exceed in amount, what is demanded in the pleadings.” As applied here, “Ditech’s demand for judicial foreclosure gave meaningful notice that, in the event of default, a writ of possession would issue in favor of the foreclosure-sale purchaser. Texas’s process of enforcing a judicial foreclosure—and specifically its mechanism for enforcing the foreclosure sale— entails issuance of the writ. Accordingly, in this case the judgment’s provision for future issuance of the writ did not expand or alter the kind or amount of relief prayed for by Ditech.” No. 17-50616 (July 19, 2018, unpublished).

An element of judicial estoppel is that “a court accepted the prior position” that is inconsistent with a party’s position in the case at hand. In Fornesa v. Fifth Third Mortgage Co., a bankruptcy debtor’s failure to amend his financial schedules satisfied that requirement, as “the bankruptcy court . . . implicitly accepted the representation by operating as though [Debtor’s] financial status were unchanged. ‘Had the court been aware . . . it may well have altered the plan.'” No. 17-20324 (July 27, 2018).

An element of judicial estoppel is that “a court accepted the prior position” that is inconsistent with a party’s position in the case at hand. In Fornesa v. Fifth Third Mortgage Co., a bankruptcy debtor’s failure to amend his financial schedules satisfied that requirement, as “the bankruptcy court . . . implicitly accepted the representation by operating as though [Debtor’s] financial status were unchanged. ‘Had the court been aware . . . it may well have altered the plan.'” No. 17-20324 (July 27, 2018).

The issue in Kirchner v. Deutsche Bank was whether a spouse’s signature on a deed of trust – but not the loan instrument – satisfied the Texas Constitution’s requirements about home equity loans. The Fifth Circuit found the issue was squarely addressed by a prior unpublished opinion, which it called “persuasive,” and affirmed – this time, in a published opinion. The broader principle is that unpublished opinions can work their way into published “status” when the issues they address are recurring ones. No. 17-50736 (July 11, 2018).

The issue in Kirchner v. Deutsche Bank was whether a spouse’s signature on a deed of trust – but not the loan instrument – satisfied the Texas Constitution’s requirements about home equity loans. The Fifth Circuit found the issue was squarely addressed by a prior unpublished opinion, which it called “persuasive,” and affirmed – this time, in a published opinion. The broader principle is that unpublished opinions can work their way into published “status” when the issues they address are recurring ones. No. 17-50736 (July 11, 2018).

A practical tidbit about whether a notice of appeal is “jurisdictional” appeared during the last SCOTUS term in Hamer v. Neighborhood Housing Services: “Several Courts of Appeals, including the Court of Appeals in Hamer’s case, have tripped over our statement in Bowles [v. Russell, 551 U. S. 205, 210–213 (2007)], that “the taking of an appeal within the prescribed time is ‘mandatory and jurisdictional.’ The ‘mandatory and jurisdictional’ formulation is a characterization left over from days when we were ‘less than meticulous’ in our use of the term ‘jurisdictional.’ The statement was correct as applied in Bowles because, as the Court there explained, the time prescription at issue in Bowles was imposed by Congress. But ‘mandatory and jurisdictional’ is erroneous and confounding terminology where, as here, the relevant time prescription is absent from the U.S. Code. Because Rule 4(a)(5)(C), not § 2107, limits the length of the extension granted here, the time prescription is not jurisdictional.” No. 16-658 (Nov. 18, 2017) (citations and footnote omitted).

A practical tidbit about whether a notice of appeal is “jurisdictional” appeared during the last SCOTUS term in Hamer v. Neighborhood Housing Services: “Several Courts of Appeals, including the Court of Appeals in Hamer’s case, have tripped over our statement in Bowles [v. Russell, 551 U. S. 205, 210–213 (2007)], that “the taking of an appeal within the prescribed time is ‘mandatory and jurisdictional.’ The ‘mandatory and jurisdictional’ formulation is a characterization left over from days when we were ‘less than meticulous’ in our use of the term ‘jurisdictional.’ The statement was correct as applied in Bowles because, as the Court there explained, the time prescription at issue in Bowles was imposed by Congress. But ‘mandatory and jurisdictional’ is erroneous and confounding terminology where, as here, the relevant time prescription is absent from the U.S. Code. Because Rule 4(a)(5)(C), not § 2107, limits the length of the extension granted here, the time prescription is not jurisdictional.” No. 16-658 (Nov. 18, 2017) (citations and footnote omitted).

Rehearing motions led to a revised panel opinion and an en banc vote in Mance v. Sessions, a Constitutional challenge to restrictions on handgun sales by an authorized federally-licensed firearm dealer, to a purchaser who lives in a different state from the dealer. The revised opinion affirming the restrictions stood, with the Court voting 9-7 against rehearing en banc. Two of the three dissents from the vote were written by recent nominees of President Trump, with all of his nominees joining the vote in favor of review. Notably, this vote reflects two vacancies at the time it was conducted (one of which has since been filled with the confirmation of Judge Oldham, and other to be filled when a nomination is made to replace Judge Jolly of Mississippi). Assuming the two nominees would join the other new judges in their view of this case, their addition would be outcome-determinative as to its en banc review.

Rehearing motions led to a revised panel opinion and an en banc vote in Mance v. Sessions, a Constitutional challenge to restrictions on handgun sales by an authorized federally-licensed firearm dealer, to a purchaser who lives in a different state from the dealer. The revised opinion affirming the restrictions stood, with the Court voting 9-7 against rehearing en banc. Two of the three dissents from the vote were written by recent nominees of President Trump, with all of his nominees joining the vote in favor of review. Notably, this vote reflects two vacancies at the time it was conducted (one of which has since been filled with the confirmation of Judge Oldham, and other to be filled when a nomination is made to replace Judge Jolly of Mississippi). Assuming the two nominees would join the other new judges in their view of this case, their addition would be outcome-determinative as to its en banc review.

The Senate has now confirmed Andrew Oldham of Texas as the newest judge on the Fifth Circuit. Congratulations and every best wish to Judge Oldham.

The Senate has now confirmed Andrew Oldham of Texas as the newest judge on the Fifth Circuit. Congratulations and every best wish to Judge Oldham.

A difficult question of administrative law produced a divided panel in Collins v. Mnuchin. The panel majority concluded that the Federal Housing Finance Agency (a regulator for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac created by Congress in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis) was unconstitutionally structured. After careful review of the Supreme Court’s precedents in the area, the panel excised a “for cause” limitation on the removal of FHFA’s director from the relevant statute, finding that with this revision “the FHFA survives as a properly supervised executive agency.” One dissent took issue with that holding; another dissent criticized the majority’s conclusion that the specific FHFA action at issue – a “net worth sweep” requiring payment of substantial quarterly dividends to the Treasury by Fannie and Freddie – was within the scope of FHFA’s statutory authority and thus insulated from judicial review. No. 17-20364 (July 16, 2018).

A difficult question of administrative law produced a divided panel in Collins v. Mnuchin. The panel majority concluded that the Federal Housing Finance Agency (a regulator for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac created by Congress in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis) was unconstitutionally structured. After careful review of the Supreme Court’s precedents in the area, the panel excised a “for cause” limitation on the removal of FHFA’s director from the relevant statute, finding that with this revision “the FHFA survives as a properly supervised executive agency.” One dissent took issue with that holding; another dissent criticized the majority’s conclusion that the specific FHFA action at issue – a “net worth sweep” requiring payment of substantial quarterly dividends to the Treasury by Fannie and Freddie – was within the scope of FHFA’s statutory authority and thus insulated from judicial review. No. 17-20364 (July 16, 2018).

A succinct case study in bankruptcy standing appears in Furlough v. Cage: “Furlough’s primary contention is that, but for NOV’s proof of claim, Technicool’s assets would exceed its debt, and he would be entitled to any estate surplus. Because SBPC represents both NOV and the Trustee, Furlough argues, it might fail to disclose any problems with NOV’s claim, robbing him of the possibility of recovering a surplus. This speculative prospect of harm is far from a direct, adverse, pecuniary hit. Furlough must clear a higher standing hurdle: The order must burden his pocket before he burdens a docket.” No. 17-20603 (July 16, 2018) (emphasis added).

A succinct case study in bankruptcy standing appears in Furlough v. Cage: “Furlough’s primary contention is that, but for NOV’s proof of claim, Technicool’s assets would exceed its debt, and he would be entitled to any estate surplus. Because SBPC represents both NOV and the Trustee, Furlough argues, it might fail to disclose any problems with NOV’s claim, robbing him of the possibility of recovering a surplus. This speculative prospect of harm is far from a direct, adverse, pecuniary hit. Furlough must clear a higher standing hurdle: The order must burden his pocket before he burdens a docket.” No. 17-20603 (July 16, 2018) (emphasis added).

An emotionally-charged lawsuit about the disposal of embryonic and fetal tissue led to an unfortunately-timed subpoena (during Holy Week) to the Texas Conference of Catholic Bishops, which in turn led to emergency appellate proceedings. The Fifth Circuit’s panel majority found the order was appealable as an interlocutory order notwithstanding Mohawk Indus. v. Carpenter, 558 U.S. 100 (2009), noting the importance of the First Amendment issues involved and that “Mohawk does not speak to the predicament of third parties, whose claims to reasonable protection from the courts have often been met with respect.” A dissenting opinion would not have accepted the interlocutory appeal, noting that mandamus was also available (although requiring a “clear and indisputable” right rather than simply a substantial question), and observing that the movants’ “failure to object to the in camera inspection [at issue] certainly forfeits an appellate challenge to it, and the affirmative act of producing the documents likely amounts to full-scale waiver.” Whole Woman’s Health v. Smith, No. 18-50484 (revised July 17, 2018).

An emotionally-charged lawsuit about the disposal of embryonic and fetal tissue led to an unfortunately-timed subpoena (during Holy Week) to the Texas Conference of Catholic Bishops, which in turn led to emergency appellate proceedings. The Fifth Circuit’s panel majority found the order was appealable as an interlocutory order notwithstanding Mohawk Indus. v. Carpenter, 558 U.S. 100 (2009), noting the importance of the First Amendment issues involved and that “Mohawk does not speak to the predicament of third parties, whose claims to reasonable protection from the courts have often been met with respect.” A dissenting opinion would not have accepted the interlocutory appeal, noting that mandamus was also available (although requiring a “clear and indisputable” right rather than simply a substantial question), and observing that the movants’ “failure to object to the in camera inspection [at issue] certainly forfeits an appellate challenge to it, and the affirmative act of producing the documents likely amounts to full-scale waiver.” Whole Woman’s Health v. Smith, No. 18-50484 (revised July 17, 2018).

Fisk Electric, a subcontractor, sued the general contractor and its surety under the Miller Act, a “federal statute that requires general contractors to secure payment to subcontractors on most federal construction projects.” Fisk claimed it was The dispute involved the inducement into of a settlement agreement; the specific issue on appeal was “whether the party alleging fraud must engage in active investigation to satisfy the standard of justifiable reliance.” In something of a counterpoint to recent Texas cases such as JP Morgan Chase v. Orca Assets, No. 15-0712 (Tex. March 23, 2018), the Court concluded that it was not, and Fisk was entitled to rely on the general contractor’s representations in these particular negotiations. Fisk Elec. Co. v. DQSI LLC, No. 17-30091 (June 29, 2018).

In-N-Out attempted to keep its employees from wearing buttons in support of the”Fight for $15″ minimum wage campaign (right, approximately actual size). The NLRB found this was an unfair labor practice and the Fifth Circuit affirmed. Presumptively unreasonable under federal labor law, In-N-Out argued that the ban fell within a “special circumstances” exception for reasons of the company’s public image and food safety. Both arguments failed, in large part because the company required the wearing of significantly larger buttons during the Christmas season and a charitable fund drive each April. In-N-Out-Burger v. NLRB, No. 17-60241 (July 6, 2018).

In-N-Out attempted to keep its employees from wearing buttons in support of the”Fight for $15″ minimum wage campaign (right, approximately actual size). The NLRB found this was an unfair labor practice and the Fifth Circuit affirmed. Presumptively unreasonable under federal labor law, In-N-Out argued that the ban fell within a “special circumstances” exception for reasons of the company’s public image and food safety. Both arguments failed, in large part because the company required the wearing of significantly larger buttons during the Christmas season and a charitable fund drive each April. In-N-Out-Burger v. NLRB, No. 17-60241 (July 6, 2018).

The plaintiffs in Firefighters’ Retirement System v. Grant Thornton LLP alleged that Grant Thornton waived its right to insist on presuit review of the claims by a review panel, as ordinarily required by Louisiana law. The Fifth Circuit rejected this argument, finding:

The plaintiffs in Firefighters’ Retirement System v. Grant Thornton LLP alleged that Grant Thornton waived its right to insist on presuit review of the claims by a review panel, as ordinarily required by Louisiana law. The Fifth Circuit rejected this argument, finding:

- Judicial estoppel did not apply to an allegedly inconsistent litigation position by Grant Thornton when the district court did not accept it (notably, stating the elements of the doctrine in a way that does not require the statement to have been made in a different proceeding), and

- Grant Thornton did not waive this requirement, distinguishing (and criticizing) a Louisiana appellate opinion on the issue, and noting that the litigation had been stayed for a lengthy period such that GT had not yet even filed an answer.

Accordingly, the court affirmed the dismissal of plaintiffs’ claims because of preemption. No. 17-30274 (July 3, 2018).

Applying Singh v. RadioShack Corp., 882 F.3d 137 (5th Cir. 2018), which in turn relied upon Fifth Third Bancorp v. Dudenhoeffer, 134 S. Ct. 2459 (2014), the Fifth Circuit rejected a duty-of-prudence claim against an ERISA fiduciary based on the defendants allowing investments to continue a troubled company’s stock. Specifically, the plaintiffs alleged that the defendants “knew that it was inappropriate to rely on the market price of Idearc stock because their own fraudulent activities had caused the public markets to overvalue Idearc stock.” The Court did not agree: “[T]he alleged fraud is by definition not public information, and [Plaintiff] does not address how this information would affect the reliability of the market price ‘as an unbiased assessment of the security’s value in light of all public information.'” No. 16-11590 (June 27, 2018).

Applying Singh v. RadioShack Corp., 882 F.3d 137 (5th Cir. 2018), which in turn relied upon Fifth Third Bancorp v. Dudenhoeffer, 134 S. Ct. 2459 (2014), the Fifth Circuit rejected a duty-of-prudence claim against an ERISA fiduciary based on the defendants allowing investments to continue a troubled company’s stock. Specifically, the plaintiffs alleged that the defendants “knew that it was inappropriate to rely on the market price of Idearc stock because their own fraudulent activities had caused the public markets to overvalue Idearc stock.” The Court did not agree: “[T]he alleged fraud is by definition not public information, and [Plaintiff] does not address how this information would affect the reliability of the market price ‘as an unbiased assessment of the security’s value in light of all public information.'” No. 16-11590 (June 27, 2018).

Courtesy of the Huffington Post, here are seven good trivia questions about the Declaration of Independence to enjoy on your July 4 holiday.

Courtesy of the Huffington Post, here are seven good trivia questions about the Declaration of Independence to enjoy on your July 4 holiday.

The judgment creditor in Century Surety Co. v. Seidel, a case involving sexual assault on an underage restaurant employee, tried valiantly to collect from the restaurant’s insurance carrier. The Fifth Circuit found that the policy’s “criminal acts” exclusion  precluded coverage, despite the plaintiff not specifically pleading that the underlying acts were criminal: “Appellants have cited no case law stating that, to trigger a criminal act exclusion, the plaintiff in the underlying suit must, in addition to describing actions that necessarily imply a crime, also specifically label those actions as criminal. Such a rule is incongruous with the plain language of the Policy and would create an artifice in criminal-act exclusions.” No. 17-10026 (June 25, 2018).

precluded coverage, despite the plaintiff not specifically pleading that the underlying acts were criminal: “Appellants have cited no case law stating that, to trigger a criminal act exclusion, the plaintiff in the underlying suit must, in addition to describing actions that necessarily imply a crime, also specifically label those actions as criminal. Such a rule is incongruous with the plain language of the Policy and would create an artifice in criminal-act exclusions.” No. 17-10026 (June 25, 2018).

A pro se complaint in a mortgage servicing dispute stated a federal claim, and thus allowed removal, when “[I]n the ‘Facts’ section . . . [Plaintiffs’] wrote: ’17. In April, 2009 BANK OF AMERICA CORPORATION claimed to be the new mortgage servicer and payments were to be made to them. BANK OF AMERICA CORPORATION was not an “original party” to the “original negotiable instrument” which the “borrowers” negotiated. BANK OF AMERICA CORPORATION was a 3rd party debt collector, pretending to be the Lender. BANK OF AMERICA CORPORATION failed to adhere to the Fair Debt Collection Practice Act, as all 3rd party debt collectors are required to do.'” The Fifth Circuit observed: “[P]laintiffs may state a claim for relief by pleading facts that support the claim. The Smiths did just that—and cited the legal theory underlying their claim. The Smiths’ explicit reference to the ‘Fair Debt Collection Practice[s] Act’ (and its position in the U.S. Code), coupled with a description of conduct that could subject the Defendants to liability under the Act, solidifies our conclusion” about federal question jurisdiction. Smith v. Barrett Daffin Frappier Turner & Engel LLP, No. 16-51010 (June 12, 2018, unpublished).

A pro se complaint in a mortgage servicing dispute stated a federal claim, and thus allowed removal, when “[I]n the ‘Facts’ section . . . [Plaintiffs’] wrote: ’17. In April, 2009 BANK OF AMERICA CORPORATION claimed to be the new mortgage servicer and payments were to be made to them. BANK OF AMERICA CORPORATION was not an “original party” to the “original negotiable instrument” which the “borrowers” negotiated. BANK OF AMERICA CORPORATION was a 3rd party debt collector, pretending to be the Lender. BANK OF AMERICA CORPORATION failed to adhere to the Fair Debt Collection Practice Act, as all 3rd party debt collectors are required to do.'” The Fifth Circuit observed: “[P]laintiffs may state a claim for relief by pleading facts that support the claim. The Smiths did just that—and cited the legal theory underlying their claim. The Smiths’ explicit reference to the ‘Fair Debt Collection Practice[s] Act’ (and its position in the U.S. Code), coupled with a description of conduct that could subject the Defendants to liability under the Act, solidifies our conclusion” about federal question jurisdiction. Smith v. Barrett Daffin Frappier Turner & Engel LLP, No. 16-51010 (June 12, 2018, unpublished).