Catic USA challenged a $63 million arbitration award about a Chinese wind-energy venture, complaining inter alia, that the panel was assembled unfairly: “[O]ne side (the plaintiffs) appointed five arbitrators, the other side (Catic USA and Thompson) only two.'” The Fifth Circuit disagreed, noting that the parties’ contract identified “seven total, signatory ‘Members,'” each of whom had the right to name an arbitrator in the event of a dispute. “This case involves two sides, but, more importantly, it features seven members; suppose Eris had tossed the Apple of Discord into a Soaring Wind conference room, prompting a free-for-all among the parties–the arbiter selection process would have remained the same.” Soaring Wind Energy LLC v. Catic USA Inc., No. 18-11192 (Jan. 7, 2020). The Court reminded that as a general matter: “It is not the court’s role to rewrite the contract between sophisticated market participants, allocating the risk of an agreement after the fact, to suit the court’s sense of equity or fairness.”

Catic USA challenged a $63 million arbitration award about a Chinese wind-energy venture, complaining inter alia, that the panel was assembled unfairly: “[O]ne side (the plaintiffs) appointed five arbitrators, the other side (Catic USA and Thompson) only two.'” The Fifth Circuit disagreed, noting that the parties’ contract identified “seven total, signatory ‘Members,'” each of whom had the right to name an arbitrator in the event of a dispute. “This case involves two sides, but, more importantly, it features seven members; suppose Eris had tossed the Apple of Discord into a Soaring Wind conference room, prompting a free-for-all among the parties–the arbiter selection process would have remained the same.” Soaring Wind Energy LLC v. Catic USA Inc., No. 18-11192 (Jan. 7, 2020). The Court reminded that as a general matter: “It is not the court’s role to rewrite the contract between sophisticated market participants, allocating the risk of an agreement after the fact, to suit the court’s sense of equity or fairness.”

In this election year, the Texas State Bar’s Judicial Poll has special significance. If you’re a Texas lawyer, haven’t voted yet and can’t locate the email from the Bar about it, just click here for your ballot by February 4.

In this election year, the Texas State Bar’s Judicial Poll has special significance. If you’re a Texas lawyer, haven’t voted yet and can’t locate the email from the Bar about it, just click here for your ballot by February 4.

“Repeatedly emphasizing that the classification turns on whether the deadline is in a statute, the Supreme Court has held that the time limits in Civil Rule 23(f), Appellate Rule 4(a)(5)(C), Criminal Rules 33 and 45, and Bankruptcy Rules 4004 and 9006 are not jurisdictional. The Court has not addressed the rule we confront, Civil Rule 50(b). But its reasoning in these cases—that “[i]t is axiomatic that the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure do not create or withdraw federal jurisdiction,”—compels the conclusion that Rule 50(b) is also a claim-processing requirement. We therefore hold that Rule 50 does not impose a jurisdictional deadline.” Escribiano v. Travis County, No. 19-50236 (Jan. 10, 2020).

“The district court’s order to stay and administratively close [Appellant]’s case is not a final order for purposes of [Federal Arbitration Act] § 16(a)(3); the collateral order doctrine does not apply to orders concerning arbitration governed by the FAA; and § 1292(a)(3) is inapplicable to referrals to arbitration in admiralty cases that do not determine a party’s substantive rights or liabilities.” Psara Energy, Ltd. v. Advantage Arrow Shipping, LLC, No. 19-40071 (Jan. 9, 2020).

“The district court’s order to stay and administratively close [Appellant]’s case is not a final order for purposes of [Federal Arbitration Act] § 16(a)(3); the collateral order doctrine does not apply to orders concerning arbitration governed by the FAA; and § 1292(a)(3) is inapplicable to referrals to arbitration in admiralty cases that do not determine a party’s substantive rights or liabilities.” Psara Energy, Ltd. v. Advantage Arrow Shipping, LLC, No. 19-40071 (Jan. 9, 2020).

Southern Credentialing showed that Hammond infringed its “credentialing packets” used for hospitals in making privilege decisions. The trial court found non-willful infringement and awarded statutory damages; Hammond appealed, arguing that such damages were not available when the alleged infringement occurred before Southern Credentialing registered its copyrights. The Fifth Circuit held: “[S]ection 412 bars statutory damage awards when a defendant violates one of the six exclusive rights of a copyright holder preregistration and violates a different right in the same work after registration. Any other conclusion would be inconsistent with the Copyright Act, which does not distinguish between ‘different’ infringements.” Southern Credentialing Support Services, LLC v. Hammond Surgical Hospital LLC, No. 18-31160 (Jan. 9, 2020).

Southern Credentialing showed that Hammond infringed its “credentialing packets” used for hospitals in making privilege decisions. The trial court found non-willful infringement and awarded statutory damages; Hammond appealed, arguing that such damages were not available when the alleged infringement occurred before Southern Credentialing registered its copyrights. The Fifth Circuit held: “[S]ection 412 bars statutory damage awards when a defendant violates one of the six exclusive rights of a copyright holder preregistration and violates a different right in the same work after registration. Any other conclusion would be inconsistent with the Copyright Act, which does not distinguish between ‘different’ infringements.” Southern Credentialing Support Services, LLC v. Hammond Surgical Hospital LLC, No. 18-31160 (Jan. 9, 2020).

Judicial-estoppel issues often surface when a debtor a seeks to assert a claim and dispute arises about the adequacy of the debtor’s disclosures about that claim. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Parker involved a debtors personal-injury claim, and the Fifth Circuit concluded: “After declining to apply judicial estoppel and thus allowing Parker to proceed with his personal injury suit against Wal-Mart, the bankruptcy court ordered Parker to turn over any recovery to the Chapter 13 trustee to be administered for the benefit of creditors. In cases similar to Wal-Mart’s—when a potential defendant argues that a debtor is estopped from bringing a lawsuit for failure to disclose it to the bankruptcy court—we have held that, while a debtor may be estopped from pursuing the claim on his own behalf, his bankruptcy trustee is not similarly estopped and may pursue the claim for the benefit of the creditors.” No. 18-30378 (Jan. 8, 2020). “Though the bankruptcy court’s decision is certainly odd and not the route we would have chosen, we cannot say that it contained clearly erroneous factual findings or the application of incorrect legal standards that amount to an abuse of discretion.”

Judicial-estoppel issues often surface when a debtor a seeks to assert a claim and dispute arises about the adequacy of the debtor’s disclosures about that claim. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Parker involved a debtors personal-injury claim, and the Fifth Circuit concluded: “After declining to apply judicial estoppel and thus allowing Parker to proceed with his personal injury suit against Wal-Mart, the bankruptcy court ordered Parker to turn over any recovery to the Chapter 13 trustee to be administered for the benefit of creditors. In cases similar to Wal-Mart’s—when a potential defendant argues that a debtor is estopped from bringing a lawsuit for failure to disclose it to the bankruptcy court—we have held that, while a debtor may be estopped from pursuing the claim on his own behalf, his bankruptcy trustee is not similarly estopped and may pursue the claim for the benefit of the creditors.” No. 18-30378 (Jan. 8, 2020). “Though the bankruptcy court’s decision is certainly odd and not the route we would have chosen, we cannot say that it contained clearly erroneous factual findings or the application of incorrect legal standards that amount to an abuse of discretion.”

A putative class action failed for lack of commonality: “Every member of the putative class received the same allegedly threatening letter from Medicredit. But the FDCPA penalizes empty threats, not all threats. So the letter alone is insufficient to certify a class. As in Dukes, there is no ‘glue’ here ‘holding the alleged reasons for all those [letters] together’—namely, evidence of a uniform intention by Seton regarding suit. So it is likewise ‘impossible to say that examination of all the class members’ claims for relief will produce a common answer to the crucial question’ why was I threatened.” Flecha v. Medicredit, Inc., No. 18-50551 (Jan. 8, 2020) (citations omitted, emphasis in original).

A putative class action failed for lack of commonality: “Every member of the putative class received the same allegedly threatening letter from Medicredit. But the FDCPA penalizes empty threats, not all threats. So the letter alone is insufficient to certify a class. As in Dukes, there is no ‘glue’ here ‘holding the alleged reasons for all those [letters] together’—namely, evidence of a uniform intention by Seton regarding suit. So it is likewise ‘impossible to say that examination of all the class members’ claims for relief will produce a common answer to the crucial question’ why was I threatened.” Flecha v. Medicredit, Inc., No. 18-50551 (Jan. 8, 2020) (citations omitted, emphasis in original).

The Fifth Circuit noted two limits on Fed. R. Evid. 407, which excludes evidence of “subsequent remedial measures” –

The Fifth Circuit noted two limits on Fed. R. Evid. 407, which excludes evidence of “subsequent remedial measures” –

1. In an overtime-pay case, with respect to an employer’s internal audit about employee classifications, the Court observed that “by themselves, post-accident investigations would not make the event ‘less likely to occur,’ only the actual implemented changes make it so.”

2. And as to exhibits in which the employer actually reclassified various employees, the Court said: “[F]ederal law mandates that Shipcom pay its nonexempt employees overtime wages. Because Shipcom is legally obligated to take these measures to comply with the FLSA, excluding evidence of Plaintiffs’ reclassification to nonexempt status would not further a social policy of encouraging employers to correctly classify their employees in the future.”

Novick v. Shipcom Wireless, Inc., No. 19-20056 (Jan. 7, 2020) (citations omitted, emphasis added).

An issue in Novick v. Shipcom Wireless, Inc., was whether the district court erred in not letting the defendant employer open and close arguments, when it had the burden of proof on the remaining disputed issues in an overtime-pay case. The Fifth Circuit held: “Shipcom has not cited, and we have not found, any case where this court has held a trial court’s decision as to which party presents argument first to be an abuse of discretion. Many legal presentations, like the FLSA claim in this case, have a beginning, a middle, and an end. It was within the discretion of the trial court to decide that in this case the jury should hear the beginning of the story first, even though the legal effect of the beginning was not in dispute.” No. 19-20056 (Jan. 7, 2020).

An issue in Novick v. Shipcom Wireless, Inc., was whether the district court erred in not letting the defendant employer open and close arguments, when it had the burden of proof on the remaining disputed issues in an overtime-pay case. The Fifth Circuit held: “Shipcom has not cited, and we have not found, any case where this court has held a trial court’s decision as to which party presents argument first to be an abuse of discretion. Many legal presentations, like the FLSA claim in this case, have a beginning, a middle, and an end. It was within the discretion of the trial court to decide that in this case the jury should hear the beginning of the story first, even though the legal effect of the beginning was not in dispute.” No. 19-20056 (Jan. 7, 2020).

Paine Snider v. L-3 Communications involved a company’s legal malpractice claim against a firm that represented it in corporate matters, when a firm partner helped a company employee with a discrimination case against the company. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of most of the malpractice claim on limitations grounds, observing:

Paine Snider v. L-3 Communications involved a company’s legal malpractice claim against a firm that represented it in corporate matters, when a firm partner helped a company employee with a discrimination case against the company. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of most of the malpractice claim on limitations grounds, observing:

L-3 knew in 2007 that . . . [i]t had access to emails between Edwards and Paine Snider reflecting that Edwards participated in drafting a detailed written internal complaint document cataloging the facts and incidents supporting Paine Snider’s claims. L-3 contacted Edwards and Elizabeth Quick, both partners at Womble, and expressly asserted that Edwards had a conflict of interest. L-3 failed to follow up with the Womble firm after it was apprised in writing by Bill Raper of that firm that he would investigate IT material, and subsequently, that he had investigated and was ready to talk to the general counsel of L-3’s parent company about Edwards’s involvement with Paine Snider’s claims against L-3.

. . .

We also know that when, late in 2011, L-3 subpoenaed documents from the Womble firm, the “new” information was somewhat more salacious and provided additional evidentiary support. But the nature of and essential facts supporting L-3’s claims against Edwards and Womble remained unchanged since 2007.

No. 16-60731 (Dec. 31, 2019).

Continuing a line of thought from earlier 2019 authority about standing to challenge administrative-agency action, the Fifth Circuit found an organization’s alleged standing was too attenuated when it “contend[ed] that its injuries are traceable to Treasury’s actions because Treasury has plenary authority over the [Low-Income Housing Tax Credit] program, including the power both to issue regulations and to recapture LIHTCs from investors who violate the [Fair Housing Act].” Inclusive Communities Project, Inc. v. Dep’t of the Treasury also shows that the style trend toward use of contractions hasn’t lessened as 2019’s continued. No. 19-10377 (Dec. 30, 2019).

Continuing a line of thought from earlier 2019 authority about standing to challenge administrative-agency action, the Fifth Circuit found an organization’s alleged standing was too attenuated when it “contend[ed] that its injuries are traceable to Treasury’s actions because Treasury has plenary authority over the [Low-Income Housing Tax Credit] program, including the power both to issue regulations and to recapture LIHTCs from investors who violate the [Fair Housing Act].” Inclusive Communities Project, Inc. v. Dep’t of the Treasury also shows that the style trend toward use of contractions hasn’t lessened as 2019’s continued. No. 19-10377 (Dec. 30, 2019).

Several amendments to the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure became effective on December 1, 2019. This House Report describes and explains them.

Several amendments to the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure became effective on December 1, 2019. This House Report describes and explains them.

The issue in BNSF Railway v. Panhandle Northern Railroad was whether a “handling-carrier” relationship between two railroads was terminable at will. BNSF contended that it was not; Panhandle Northern, a short line operating between BNSF’s cross-country track and a large complex of chemical plants in the Texas Panhandle, argued that it was. The Fifth Circuit made a detailed “Erie guess” about the construction of the parties’ contract under the controlling Illinois law, and rendered judgment in favor of Panhandle Northern:

The issue in BNSF Railway v. Panhandle Northern Railroad was whether a “handling-carrier” relationship between two railroads was terminable at will. BNSF contended that it was not; Panhandle Northern, a short line operating between BNSF’s cross-country track and a large complex of chemical plants in the Texas Panhandle, argued that it was. The Fifth Circuit made a detailed “Erie guess” about the construction of the parties’ contract under the controlling Illinois law, and rendered judgment in favor of Panhandle Northern:

“[I]in making an Erie guess, we must determine, in our best judgment, how we believe the Illinois Supreme Court would resolve whether the handling-carrier relationship between PNR and BNSF is terminable at will. And, as reflected in the [key Illinois Supreme Court] decision, careful analysis of the text of the contract is paramount in making such a determination. Moreover, in the cases BNSF relies upon, the courts discussed the economics of the parties’ agreements only after first examining closely the text of the contracts at issue and determining that there were termination provisions sufficient to take the contracts of indefinite duration out of the general rule of at-will termination. Although the courts could have ended their decisions upon making those determinations, they then went on to discuss the economics of the parties’ agreements to further bolster their decisions that the contracts were not terminable at will.”

No. 18-11416 (Jan. 3, 2020). (LPCH represented the successful appellant in this case.)

In a dispute about the allocation of a fee award in a successful class action case, the trial court expressly declined to follow the customary factors about reasonableness, instead focusing on the equities of earlier agreements among counsel. Applying a prior Circuit case on the issue, the Fifth Circuit reversed: “Although sympathetic to the difficult task the lawyers gave to the district court, we must vacate the award allocating attorney’s fees and remand for proceedings consistent with this opinion and with due consideration of the Johnson factors. While nothing forecloses an agreement among all, its absence leaves no choice but to ‘do it by the book.’ The result will be ‘equitable’ but not necessarily the extant result.” Torres v. SGE Management, LLC, No. 18-20801 (Dec.18, 2019).

In a dispute about the allocation of a fee award in a successful class action case, the trial court expressly declined to follow the customary factors about reasonableness, instead focusing on the equities of earlier agreements among counsel. Applying a prior Circuit case on the issue, the Fifth Circuit reversed: “Although sympathetic to the difficult task the lawyers gave to the district court, we must vacate the award allocating attorney’s fees and remand for proceedings consistent with this opinion and with due consideration of the Johnson factors. While nothing forecloses an agreement among all, its absence leaves no choice but to ‘do it by the book.’ The result will be ‘equitable’ but not necessarily the extant result.” Torres v. SGE Management, LLC, No. 18-20801 (Dec.18, 2019).

When planning your next trip to New Orleans, be sure to check the 2020 Mardi Gras parade schedule! Mardi Gras falls on February 25 this year.

Ms. Whitlock received a large amount of money from the DeBerrys in September 2013, and returned $241,000 of it to them in October. In early 2014, Mr. DeBerry filed for bankruptcy. The trustee of his bankruptcy estate sought recovery of the 2013 transfer from Ms. Whitlock. The Fifth Circuit agreed with her that the $241,000 was not recoverable because it had already been returned to the estate before filing of the bankruptcy petition:

Ms. Whitlock received a large amount of money from the DeBerrys in September 2013, and returned $241,000 of it to them in October. In early 2014, Mr. DeBerry filed for bankruptcy. The trustee of his bankruptcy estate sought recovery of the 2013 transfer from Ms. Whitlock. The Fifth Circuit agreed with her that the $241,000 was not recoverable because it had already been returned to the estate before filing of the bankruptcy petition:

In matters of statutory interpretation, text is always the alpha. Here, it’s also the omega. Section 550(a) permits the trustee to “recover” the property. To “recover” means “[t]o get back or regain in full or in equivalence.” Obtaining a duplicate of something is not getting it back; it’s getting a windfall. Property that has already been returned cannot be “recovered” in any meaningful sense. And that principle defeats the Trustee’s claims against Ms. Whitlock. Once the fraudulently transferred property has been returned, the bankruptcy trustee cannot “recover” it again using § 550(a)

Whitlock v. Lowe, No. 18-50335 (Dec. 23, 2019) (citations omitted) (emphasis added).

A Chevron dispute about the Department of the Interior’s collection of natural gas royalties led to the question whether “the agency must credit all of W&T’s prior overdeliveries in calculating the cumulative delivery shortfall.” Observing that the defense of “equitable recoupment is ‘never barred by the statute of limitations so long as the main action itself is timely,'” the Fifth Circuit rejected the Department’s three arguments against its application – looking to three common reference points for resolving such disputes:

A Chevron dispute about the Department of the Interior’s collection of natural gas royalties led to the question whether “the agency must credit all of W&T’s prior overdeliveries in calculating the cumulative delivery shortfall.” Observing that the defense of “equitable recoupment is ‘never barred by the statute of limitations so long as the main action itself is timely,'” the Fifth Circuit rejected the Department’s three arguments against its application – looking to three common reference points for resolving such disputes:

- Statutory limitations. A statutory prohibition on “pursu[it of] any other equitable or legal remedy, whether under statute or common law” did not clearly preclude the assertion of this defense;

- Factual linkage. “This objection is easily dispatched, as the Department of the Interior’s requirement that payments be made on a monthly basis does not trump the reality that each monthly obligation arises from a single contract: the lease.

- Overall equities. The Department’s facially “neutral application of the statute of limitations across the industry does not counteract the inequitable result that W&T suffered . . . .”

W&T Offshore v. Bernhardt, No. 18-30876 (Dec. 23, 2019).

Schrödinger’s Cat, wily feline that it is, made a cameo in yesterday’s Affordable Care Act opinion. Rebutting a point made by the dissent, the panel majority observed:

Schrödinger’s Cat, wily feline that it is, made a cameo in yesterday’s Affordable Care Act opinion. Rebutting a point made by the dissent, the panel majority observed:

The dissenting opinion’s theory of the “law that does nothing” results in some bizarre metaphysical conclusions. The ACA was signed into law in 2010. No one questions that when it was signed, § 5000A was an exercise of legislative power. Yet today, the dissenting opinion asserts, § 5000A is not an exercise of legislative power. So did Congress exercise legislative power in 2010, as seen from 2015? As seen from 2018? Does § 5000A ontologically re-emerge should a future Congress restore the shared responsibility payment? Perhaps, like Schrödinger’s cat, § 5000A exists in both states simultaneously. The dissenting opinion does not say. Our approach requires no such quantum musings.

Slip op. at 43 n.38 (emphasis added).

The Fifth Circuit has ruled in the closely-watched constitutional challenge to the Affordable Care Act, Texas v. United States, No. 19-10011 (Dec. 18, 2019). The panel majority opinion, written by Judge Elrod and joined by Judge Englehardt, held:

First, there is a live case or controversy because the intervenor-defendant states have standing to appeal and, even if they did not, there remains a live case or controversy between the plaintiffs and the federal defendants. Second, the plaintiffs have Article III standing to bring this challenge to the ACA; the individual mandate injures both the individual plaintiffs, by requiring them to buy insurance that they do not want, and the state plaintiffs, by increasing their costs of complying with the reporting requirements that accompany the individual mandate. Third, the individual mandate is unconstitutional because it can no longer be read as a tax, and there is no other constitutional provision that justifies this exercise of congressional power. Fourth, on the severability question, we remand to the district court to provide additional analysis of the provisions of the ACA as they currently exist.

(emphasis added). Judge King dissented, stating: “I would vacate the district court’s order because none of the plaintiffs have standing to challenge the coverage requirement. And although I would not reach the merits or remedial issues, if I did, I would conclude that the coverage requirement is constitutional, albeit unenforceable, and entirely severable from the remainder of the Affordable Care Act.”

Appellants complained about the treatment of their claims by the system established to resolve the “Chinese-Manufactured Drywall Products Liability Multi-District Litigation.” They contended that “a disagreement with the District Court’s interpretation and application of the settlement agreement invalidates the waivers” of appeal rights in that agreement. The Fifth Circuit disagreed, concluding that this argument “negates the entire purpose of the appeal waiver and would render these agreed upon terms meaningless,” and reminding that to make such a waiver, “a party need only understand the right to appeal that is given up, not all the facts relating to all potential challenges that could be raised on appeal.” Asch v. Gebrueder Knauf, No. 18-31223 (Dec. 12, 2019, unpublished).

Appellants complained about the treatment of their claims by the system established to resolve the “Chinese-Manufactured Drywall Products Liability Multi-District Litigation.” They contended that “a disagreement with the District Court’s interpretation and application of the settlement agreement invalidates the waivers” of appeal rights in that agreement. The Fifth Circuit disagreed, concluding that this argument “negates the entire purpose of the appeal waiver and would render these agreed upon terms meaningless,” and reminding that to make such a waiver, “a party need only understand the right to appeal that is given up, not all the facts relating to all potential challenges that could be raised on appeal.” Asch v. Gebrueder Knauf, No. 18-31223 (Dec. 12, 2019, unpublished).

A $61,000 jury verdict for allegedly unfair debt collection practices turned on whether the debt at issue was a consumer debt; specifically, whether “the jury could reasonably infer that the Synchrony Bank dept at issue was the QVC credit card, which was used exclusively for personal purchases, and, therefore, a consumer debt.” Jones v. Portfolio Recovery Associates LLC, No 18-50703 (Dec. 12, 2019, unpubl.) The Fifth Circuit reversed the trial court’s grant of JMOL on this issue, rejecting four arguments by the defendant that involved “two jury functions: drawing inferences and making credibility determinations.” The Court concluded: “Though it may have been simpler for Jones to explicitly connect these dots for the jury, her failure to do so is not enough to overturn the jury’s verdict. We permit—and in fact implore—juries to process contradictory information and make inferences to reach a verdict. And that is what this jury did. It was not the clearest path to victory for Jones, but it was a reasonable path, which is all we require.”

A $61,000 jury verdict for allegedly unfair debt collection practices turned on whether the debt at issue was a consumer debt; specifically, whether “the jury could reasonably infer that the Synchrony Bank dept at issue was the QVC credit card, which was used exclusively for personal purchases, and, therefore, a consumer debt.” Jones v. Portfolio Recovery Associates LLC, No 18-50703 (Dec. 12, 2019, unpubl.) The Fifth Circuit reversed the trial court’s grant of JMOL on this issue, rejecting four arguments by the defendant that involved “two jury functions: drawing inferences and making credibility determinations.” The Court concluded: “Though it may have been simpler for Jones to explicitly connect these dots for the jury, her failure to do so is not enough to overturn the jury’s verdict. We permit—and in fact implore—juries to process contradictory information and make inferences to reach a verdict. And that is what this jury did. It was not the clearest path to victory for Jones, but it was a reasonable path, which is all we require.”

Plaintiff, suing in his capacity as “God of the Earth Realm” and “Trust Protector of the American Indian Tribe of משֶׁ ה Moses,” complained of, inter alia, conspiracy between the United States and Louisiana to monopolize “intergalactic foreign trade” and sought a “declaration of rights guaranteed . . . by the 1795 Spanish Treaty with the Catholic Majesty of Spain.” Perhaps a Martian or Venusian court will have jurisdiction over his claim, but the Western District of Louisiana does not, as the Fifth Circuit affirmed its finding that it lacked jurisdiction “because the claim[s] asserted [are] so attenuated and unsubstantial as to be absolutely devoid of merit.” Atakapa Indian de Creole Nation v. Louisiana, No. 19-30032 (Dec. 10, 2019).

Plaintiff, suing in his capacity as “God of the Earth Realm” and “Trust Protector of the American Indian Tribe of משֶׁ ה Moses,” complained of, inter alia, conspiracy between the United States and Louisiana to monopolize “intergalactic foreign trade” and sought a “declaration of rights guaranteed . . . by the 1795 Spanish Treaty with the Catholic Majesty of Spain.” Perhaps a Martian or Venusian court will have jurisdiction over his claim, but the Western District of Louisiana does not, as the Fifth Circuit affirmed its finding that it lacked jurisdiction “because the claim[s] asserted [are] so attenuated and unsubstantial as to be absolutely devoid of merit.” Atakapa Indian de Creole Nation v. Louisiana, No. 19-30032 (Dec. 10, 2019).

Three provocative cases are set for en banc consideration by the full Fifth Circuit (with some minor variations due to recusals and senior-judge participation) on January 22-23, 2020:

Three provocative cases are set for en banc consideration by the full Fifth Circuit (with some minor variations due to recusals and senior-judge participation) on January 22-23, 2020:

- Thomas v. Bryant, No. 19-60133, a Voting Rights Act case about a state senate district in the Mississippi Delta;

- Brackeen v. Bernhardt, No. 18-11479, which presents an important Indian law issue interwoven with fundamental administrative law concepts; and

- Williams v. Taylor Seidenbach, Inc., No. 18-31159, an effort to resolve the “finality trap” about appeals from from trial-court rulings made without prejudice.

The Fifth Circuit found that the Ex Parte Young exception to Eleventh-Amendment immunity (Mr. Young appears to the right) did not apply to the Texas Attorney General’s potential enforcement of a statute that was in conflict with a City of Austin ordinance: “[N]one of the cases the City cites to demonstrate the Attorney General’s ‘habit’ of intervening in suits involving municipal ordinances to ‘enforce the supremacy of state law’ have any overlapping facts with this case or are even remotely related to the Ordinance. And the

The Fifth Circuit found that the Ex Parte Young exception to Eleventh-Amendment immunity (Mr. Young appears to the right) did not apply to the Texas Attorney General’s potential enforcement of a statute that was in conflict with a City of Austin ordinance: “[N]one of the cases the City cites to demonstrate the Attorney General’s ‘habit’ of intervening in suits involving municipal ordinances to ‘enforce the supremacy of state law’ have any overlapping facts with this case or are even remotely related to the Ordinance. And the  mere fact that the Attorney General has the authority to enforce § 250.007 cannot be said to ‘constrain’ the City from enforcing the Ordinance. The City simply provides no evidence that the Attorney General may “similarly bring a proceeding” to enforce § 250.007: that he has chosen to intervene to defend different statutes under different circumstances does not show that he is likely to do the same here. . . . Thus, we find that Attorney General Paxton lacks the requisite ‘connection to the enforcement’ of § 250.007.” City of Austin v. Paxton, No. 18-50646 (Dec. 4, 2019).

mere fact that the Attorney General has the authority to enforce § 250.007 cannot be said to ‘constrain’ the City from enforcing the Ordinance. The City simply provides no evidence that the Attorney General may “similarly bring a proceeding” to enforce § 250.007: that he has chosen to intervene to defend different statutes under different circumstances does not show that he is likely to do the same here. . . . Thus, we find that Attorney General Paxton lacks the requisite ‘connection to the enforcement’ of § 250.007.” City of Austin v. Paxton, No. 18-50646 (Dec. 4, 2019).

“Here, however, we have an appeal from grant of a motion to dismiss without prejudice to refile. It is not a final judgment because ‘the district court did not adjudicate or dispose of any substantive issues on the merits.'” The King-Morocco v. Banner of N.O., L.L.C., No. 19-30323 (Nov. 27, 2019) (unpubl.) (citations omitted).

“Here, however, we have an appeal from grant of a motion to dismiss without prejudice to refile. It is not a final judgment because ‘the district court did not adjudicate or dispose of any substantive issues on the merits.'” The King-Morocco v. Banner of N.O., L.L.C., No. 19-30323 (Nov. 27, 2019) (unpubl.) (citations omitted).

The GSA’s page about the John Minor Wisdom Courthouse offers a free poster for download of the building’s striking “Great Hall.”

The GSA’s page about the John Minor Wisdom Courthouse offers a free poster for download of the building’s striking “Great Hall.”

The Fifth Circuit affirmed a Tax Court decision about a $52 million “bad debt” deduction, observing: “Baker Hughes’ authorities all involved a bona fide debt. … No authority shown to us holds that a bad-debt deduction applies to a guarantor’s payment on a guarantee that does not create a debtor-creditor relationship with the party whose original obligation is extinguished.” Baker Hughes Inc. v. United States, No. 18-20585 (Nov. 21, 2019).

The Fifth Circuit affirmed a Tax Court decision about a $52 million “bad debt” deduction, observing: “Baker Hughes’ authorities all involved a bona fide debt. … No authority shown to us holds that a bad-debt deduction applies to a guarantor’s payment on a guarantee that does not create a debtor-creditor relationship with the party whose original obligation is extinguished.” Baker Hughes Inc. v. United States, No. 18-20585 (Nov. 21, 2019).

Diece-Lisa Indus., Inc. v. Disney Enterprises, Inc., a dispute about trademark rights related to “Lots-O’-Huggin’ Bear” (right), analyzed whether the disposition of several consolidated cases on personal-jurisdiction grounds could be reviewed. After reviewing the specific claims and the applicable standards, the Fifth Circuit “conclude[d] that we have jurisdiction to review the interlocutory orders . . . because they can be ‘regarded as merged into the final judgment terminating'” one of the case numbers. It then affirmed, finding that the plaintiffs’ “franchise theory” (a kind of single-business-enterprise argument) lacked merit, and that a nonexclusive license agreement also was not, by itself, a basis for jurisdiction. No. 17-41268 (Nov. 19, 2019).

Diece-Lisa Indus., Inc. v. Disney Enterprises, Inc., a dispute about trademark rights related to “Lots-O’-Huggin’ Bear” (right), analyzed whether the disposition of several consolidated cases on personal-jurisdiction grounds could be reviewed. After reviewing the specific claims and the applicable standards, the Fifth Circuit “conclude[d] that we have jurisdiction to review the interlocutory orders . . . because they can be ‘regarded as merged into the final judgment terminating'” one of the case numbers. It then affirmed, finding that the plaintiffs’ “franchise theory” (a kind of single-business-enterprise argument) lacked merit, and that a nonexclusive license agreement also was not, by itself, a basis for jurisdiction. No. 17-41268 (Nov. 19, 2019).

In the 1200s, Henry III was protected from suit by sovereign immunity, as chronicled by the prolific Bracton;

In the 1200s, Henry III was protected from suit by sovereign immunity, as chronicled by the prolific Bracton;- In the 1780s, “Brutus,” the Anti-Federalist, debated with Alexander Hamilton about whether the Constitution would undermine sovereign immunity by allowing debilitating federal-court lawsuits against states about Revolutionary War debts;

- The Eleventh Amendment was ratified in 1796 to address those concerns and prevent, inter alia, federal-court suits “prosecuted against one of the United States by Citizens of another State . . . .” (emphasis added);

- Some time later, Kathie Cutrer sued the Tarrant County Local Workforce Development Board, in federal court under federal law, for discriminating against her because of severe back problems;

- The Fifth Circuit reversed the dismissal of her claim on sovereign-immunity grounds, observing, inter alia: “Because Tarrant County, the City of Arlington, and the City of Fort Worth are not the State of Texas, they obviously cannot confer the State’s sovereign immunity upon a board by interlocal agreement. They can’t give what they don’t have.” (emphasis added). Cutrer v. Tarrant County Local Workforce Development Board, No. 18-11092 (Nov. 22, 2019) (Oldham J., joined in the judgment only by Graves and Wiener, JJ.) (Footnote 1 of the opinion also explains why Texas refers to a county adminstrator as a “county judge,” tracing the answer to the position of “alcalde” in Spanish law.)

In Williams v. TH Healthcare Ltd., No. 19-20134 (Nov. 14, 2019, unpubl.), the Fifth Circuit made two broadly-applicable points about the deadline running from receipt of an EEOC right-to-sue letter:

In Williams v. TH Healthcare Ltd., No. 19-20134 (Nov. 14, 2019, unpubl.), the Fifth Circuit made two broadly-applicable points about the deadline running from receipt of an EEOC right-to-sue letter:

- Extra days for the weekend. Williams received a right-to-sue letter for her Title VII and ADA claims on July 29, 2018. The ninety-day deadline for filing suit fell on Saturday, October 27, 2018. Williams thus had until the following Monday, October 29, 2018, to file suit. Williams filed suit that day. Her lawsuit was therefore timely and the district court erred in dismissing it.

- Substantive, but not jurisdictional. “he district court concluded that it “d[id] not have jurisdiction over Dovie Williams’s claims because she did not sue within ninety days of receiving the [right-to-sue] letter.” The ninety-day filing requirement, however, “is not a jurisdictional prerequisite, but more akin to a statute of limitations.” Harris v. Boyd Tunica, Inc., 628 F.3d 237, 239 (5th Cir. 2010). The court therefore treats the district court’s order as a dismissal of Williams’s claims pursuant to Rule 12(b)(6) for failing to comply with the ninety-day filing requirement.

A mismatch between counsel’s activity and the results obtained led to a substantial revision of the “lodestar” in Portillo v. Permanent Workers LLC, No. 18-31238 (Nov. 11, 2018) (unpublished): “[A] drastic reduction from the requested fees is called for by deleting some of the hours consumed and otherwise departing from the lodestar. Spending tens of thousands of dollars to recover $1305 makes little sense. Although the degree of success may not be the only factor considered, it weighs heavily here, particularly since no overarching principle was vindicated, no problem solved.” (citations omitted). (Above, a picture of a Lockheed C-60 “Lodestar”, a civilian airliner and military transport during World War II.)

A mismatch between counsel’s activity and the results obtained led to a substantial revision of the “lodestar” in Portillo v. Permanent Workers LLC, No. 18-31238 (Nov. 11, 2018) (unpublished): “[A] drastic reduction from the requested fees is called for by deleting some of the hours consumed and otherwise departing from the lodestar. Spending tens of thousands of dollars to recover $1305 makes little sense. Although the degree of success may not be the only factor considered, it weighs heavily here, particularly since no overarching principle was vindicated, no problem solved.” (citations omitted). (Above, a picture of a Lockheed C-60 “Lodestar”, a civilian airliner and military transport during World War II.)

“Since the issue of whether the district court applied the correct state’s law to resolve the matters before it is of primary importance in determining whether the district court ultimately reached the correct result in granting Gray’s request for summary judgment, we reject Gray’s categorization of its appeal as ‘conditional.’ Either the district court applied the correct law, or it did not. Whether the district court applied the correct law cannot and does not revolve on whether it reached a result that benefits Gray. Thus, we will address the propriety of the district court’s decision to apply Texas law regardless of whether we agree with the court’s conclusion under Texas law.” Aggreko LLC v. Chartis Specialty Ins. Co., No. 18-40325 (Nov. 11, 2019).

“Since the issue of whether the district court applied the correct state’s law to resolve the matters before it is of primary importance in determining whether the district court ultimately reached the correct result in granting Gray’s request for summary judgment, we reject Gray’s categorization of its appeal as ‘conditional.’ Either the district court applied the correct law, or it did not. Whether the district court applied the correct law cannot and does not revolve on whether it reached a result that benefits Gray. Thus, we will address the propriety of the district court’s decision to apply Texas law regardless of whether we agree with the court’s conclusion under Texas law.” Aggreko LLC v. Chartis Specialty Ins. Co., No. 18-40325 (Nov. 11, 2019).

“[T]he plain language of the [Louisiana Lease of Movables Act] forbids a lessor from both repossessing leased equipment and collecting accelerated future rental payments. Because the Lease’s liquidated damages clause authorizes just this combination of remedies, the district court properly held it unenforceable. We, like the district court, ‘agree[] with Prince that lessors cannot be allowed to circumvent Louisiana law by simply including a lease provision allowing liquidated damages in the amount of future rent payments.’” Bank of the West v. Prince, No. 18-30970 (Nov. 12, 2019).

“[T]he plain language of the [Louisiana Lease of Movables Act] forbids a lessor from both repossessing leased equipment and collecting accelerated future rental payments. Because the Lease’s liquidated damages clause authorizes just this combination of remedies, the district court properly held it unenforceable. We, like the district court, ‘agree[] with Prince that lessors cannot be allowed to circumvent Louisiana law by simply including a lease provision allowing liquidated damages in the amount of future rent payments.’” Bank of the West v. Prince, No. 18-30970 (Nov. 12, 2019).

The en banc Fifth Circuit will consider the panel opinion in Williams v. Taylor-Seidenbach, Inc., No. 18-31159 (Aug. 15, 2019), which continued to find a lack of appellate jurisdiction over a dispute because of the so-called “finality trap.” In a previous appeal, the Court found a lack of appellate jurisdiction over an order after three defendants had been dismissed without prejudice. The plaintiff returned to district

The en banc Fifth Circuit will consider the panel opinion in Williams v. Taylor-Seidenbach, Inc., No. 18-31159 (Aug. 15, 2019), which continued to find a lack of appellate jurisdiction over a dispute because of the so-called “finality trap.” In a previous appeal, the Court found a lack of appellate jurisdiction over an order after three defendants had been dismissed without prejudice. The plaintiff returned to district  court and obtained a new order directing dismissal with prejudice (with some caveats), but to no avail: “[T]he rule 54(b) judgment did not retroactively transform the prior without-prejudice dismissals into with-prejudice dismissals. . . . [T]he finality trap, which was found to bar appellate jurisdiction in Williams I, remains shut.” Judge Haynes’s concurrence in the panel opinion asked for en banc review of the Fifth Circuit’s cases on this topic.

court and obtained a new order directing dismissal with prejudice (with some caveats), but to no avail: “[T]he rule 54(b) judgment did not retroactively transform the prior without-prejudice dismissals into with-prejudice dismissals. . . . [T]he finality trap, which was found to bar appellate jurisdiction in Williams I, remains shut.” Judge Haynes’s concurrence in the panel opinion asked for en banc review of the Fifth Circuit’s cases on this topic.

Jones, the heir of a former member of the Dixie Cups, a Louisiana-based musical group, sued the Artist Rights Enforcement Corporation in Louisiana for mishandling royalties. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of Jones’s case for lack of personal jurisdiction, observing:

Jones, the heir of a former member of the Dixie Cups, a Louisiana-based musical group, sued the Artist Rights Enforcement Corporation in Louisiana for mishandling royalties. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of Jones’s case for lack of personal jurisdiction, observing:

- The contract was not signed in Louisiana;

- “Even if the contract was discussed and drafted in Louisiana, the exchange of communications in carrying out a contract is not enough to establish personal jurisdiction”;

- Jones had nothing to do with any Louisiana-based discussions in any event;

- “When royalties were collected, they were sent to New York and stored in a New York bank”; and

- “Although AREC sent payments to Louisiana, this [was] . . . only because [the former band member] resided there, which fails to establish purposeful minimum contacts.”

Jones v. Artists Rights Enf. Corp., No. 19-30374 (Oct. 22, 2019) (unpublished).

The full Fifth Circuit has voted to rehear Brackeen v. Bernhardt, an important case about the Indian Child Welfare Act with broader ramifications for administrative law generally. Judge Ho is recused; Senior Judge Wiener will join the en banc court for this case because he served on the panel.

The full Fifth Circuit has voted to rehear Brackeen v. Bernhardt, an important case about the Indian Child Welfare Act with broader ramifications for administrative law generally. Judge Ho is recused; Senior Judge Wiener will join the en banc court for this case because he served on the panel.

The Fifth Circuit reversed an OSHA determination that a company had failed to justify an untimely response, noting that under Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(1) (which OSHA has adopted for this particular situation): “The excusable neglect inquiry is not limited to whether a party’s mistake caused the delay, such cause being expressed in the term ‘neglect,’ but equally concerns whether the party’s mistake or omission was ‘excusable.’ Focusing narrowly on whether a party is at fault for the delay and denying relief if it bears any blame clearly conflicts with Pioneer‘s more lenient and comprehensive standard.” Coleman Hammons Constr. Co. v. OSHA, No. 18-60559 (Nov. 6, 2019).

The Fifth Circuit reversed an OSHA determination that a company had failed to justify an untimely response, noting that under Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(1) (which OSHA has adopted for this particular situation): “The excusable neglect inquiry is not limited to whether a party’s mistake caused the delay, such cause being expressed in the term ‘neglect,’ but equally concerns whether the party’s mistake or omission was ‘excusable.’ Focusing narrowly on whether a party is at fault for the delay and denying relief if it bears any blame clearly conflicts with Pioneer‘s more lenient and comprehensive standard.” Coleman Hammons Constr. Co. v. OSHA, No. 18-60559 (Nov. 6, 2019).

“Appellants argue that, by finding disgorgement a ‘penalty’ under [28] § 2462, Kokesh necessarily also decided that disgorgement is not an equitable remedy courts may impose in SEC enforcement proceedings. We disagree. Kokesh itself expressly declined to address that question, and so our precedent upholding district court authority to order disgorgement controls.” SEC v. Team Resources Inc., No. 18-10931 (Nov. 5, 2019).

“Appellants argue that, by finding disgorgement a ‘penalty’ under [28] § 2462, Kokesh necessarily also decided that disgorgement is not an equitable remedy courts may impose in SEC enforcement proceedings. We disagree. Kokesh itself expressly declined to address that question, and so our precedent upholding district court authority to order disgorgement controls.” SEC v. Team Resources Inc., No. 18-10931 (Nov. 5, 2019).

UCC section 9.404(a)(2) say that “the rights of an assignee are subject to . . . any other defense or claim of the account debtor against the assignor that accrues before the account debtor receives a notification of the assignment authenticated by the assignor or the assignee.” Applying this provision, the Fifth Circuit held: “Filing a financing statement does not provide actual notice. Without an inquiry duty, [debtor]’s failure to find the financing statement is not ‘actual notice.’ Because the facts presented do not support the conclusion of actual notice, the district court should have granted judgment in favor of [debtor].” Finserv Casualty Co. v. Symetra Life Ins. Co., No. 18-20245 (Oct. 29, 2019). The Court acknowledged that a sufficient factual record could establish actual notice, but found that this one did not do so: “Although [debtor] knew that the payments might be assigned, and even if it knew that such payments were routinely assigned in the structured-settlement industry, it could not have had more than a suspicion that the payments had in fact been assigned.”

UCC section 9.404(a)(2) say that “the rights of an assignee are subject to . . . any other defense or claim of the account debtor against the assignor that accrues before the account debtor receives a notification of the assignment authenticated by the assignor or the assignee.” Applying this provision, the Fifth Circuit held: “Filing a financing statement does not provide actual notice. Without an inquiry duty, [debtor]’s failure to find the financing statement is not ‘actual notice.’ Because the facts presented do not support the conclusion of actual notice, the district court should have granted judgment in favor of [debtor].” Finserv Casualty Co. v. Symetra Life Ins. Co., No. 18-20245 (Oct. 29, 2019). The Court acknowledged that a sufficient factual record could establish actual notice, but found that this one did not do so: “Although [debtor] knew that the payments might be assigned, and even if it knew that such payments were routinely assigned in the structured-settlement industry, it could not have had more than a suspicion that the payments had in fact been assigned.”

An excellent recent article in Law360 summarizes the state of the sometimes-Byzantine structure of Texas’s intermediate appellate courts. The article is behind Law360’s paywall but my remarks are below:

The Fifth Circuit affirmed a preliminary injunction that enforced a (reformed) noncompetition agreement under Louisiana law, observing, inter alia:

The Fifth Circuit affirmed a preliminary injunction that enforced a (reformed) noncompetition agreement under Louisiana law, observing, inter alia:

- The reformed scope was acceptable. “Rogillio’s non-compete provision specified particular parishes and the municipality of New Orleans. The reformation served only to narrow the provision’s scope by removing catch-all clauses that went beyond the listed parishes, not to identify specific parishes after the fact”; and

- Parol evidence was admissible to resolve an ambiguity in the agreement about the significance of the defendant’s physical presence in the relevant parishes, as the agreement’s integration clause dealt with a different and distinct issue.

Brock Services LLC v. Rogillio, 936 F.3d 290 (5th Cir. 2019).

In a case about whether a debtor’s discharge order could be enforced in a district other than the one that entered the order – a difficult question generating much analysis over the years – the Fifth Circuit “adopt[s] the language of the Second Circuit that returning to the issuing bankruptcy court to enforce an injunction is required at least in order to up hold ‘respect for judicial process.’ The bankruptcy court erred in holding that it could address contempt for violations of injunctions arising from discharges by bankruptcy courts in other districts. Therefore, as to . . . those debtors whose discharges were entered by courts in other districts, the bankruptcy court in these proceedings has no authority to enforce the resulting injunction.” Crocker v. Navient Solutions LLC, No. 18-20254 (Oct. 21, 2019) (citation omitted). This holding was fatal to an effort to bring a class action about the alleged mishandling of a type of student-loan debt.

In a case about whether a debtor’s discharge order could be enforced in a district other than the one that entered the order – a difficult question generating much analysis over the years – the Fifth Circuit “adopt[s] the language of the Second Circuit that returning to the issuing bankruptcy court to enforce an injunction is required at least in order to up hold ‘respect for judicial process.’ The bankruptcy court erred in holding that it could address contempt for violations of injunctions arising from discharges by bankruptcy courts in other districts. Therefore, as to . . . those debtors whose discharges were entered by courts in other districts, the bankruptcy court in these proceedings has no authority to enforce the resulting injunction.” Crocker v. Navient Solutions LLC, No. 18-20254 (Oct. 21, 2019) (citation omitted). This holding was fatal to an effort to bring a class action about the alleged mishandling of a type of student-loan debt.

David Russell paid money to Ellen Yarrell, and by doing so argued that he discharged a debt to his ex-wife Janna Russell. The Fifth Circuit agreed with the district court that this payment was ineffective because Yarrell was not Janna’s agent at the time,

David Russell paid money to Ellen Yarrell, and by doing so argued that he discharged a debt to his ex-wife Janna Russell. The Fifth Circuit agreed with the district court that this payment was ineffective because Yarrell was not Janna’s agent at the time,

As to express agency, the relevant court order required that any negotiable instrument “shall be made payable to ‘Janna Russell’ only and shall not have any other endorsement.” As to apparent agency, while Yarrell was still an attorney of record for Janna at the time, that general relationship did not control over David’s specific awareness that Yarrell was not authorized to serve as Janna’s agent on this specific issue. Russell v. Russell, No. 18-20643 (Oct. 21, 2019).

Practice tip: The Court noted the black-letter principles that “whether . . . authority exists ‘depends  on some communication by the principal either to the agent (actual or express authority) or to the third party (apparent or implied authority).’ It does not depend on whether the principal benefits from the transaction.“ (citation omitted, emphasis added). The Court noted, though, that neither party had raised the issue of ratification. Principles of restitution could also potentially come into play depending on the relationship between the alleged principal and agent.

on some communication by the principal either to the agent (actual or express authority) or to the third party (apparent or implied authority).’ It does not depend on whether the principal benefits from the transaction.“ (citation omitted, emphasis added). The Court noted, though, that neither party had raised the issue of ratification. Principles of restitution could also potentially come into play depending on the relationship between the alleged principal and agent.

“This case is a perfect example of when we should certify cases, and why certification is valuable. We are presented with a question of pure statutory interpretation on a recurring issue of interest to citizens and businesses across Texas. What’s more, it is a question that divided judges on this court. As reflected in our competing concurring opinions, different judges on this court have disagreed about whether the district court correctly interpreted the Texas Sales Representative Act (“TSRA”). But we all agreed that reasonable minds could differ. So rather than provide a partial answer—binding only litigants who file in federal court, not those in state court— we instead certified the question to the Supreme Court of Texas, which can speak with authority for all litigants, in state and federal court alike. We now have that answer, and accordingly affirm in part and reverse and remand in part.” JCB Inc. v. Horsburgh & Scott Co., No. 17-51023 (Oct. 17, 2019).

“This case is a perfect example of when we should certify cases, and why certification is valuable. We are presented with a question of pure statutory interpretation on a recurring issue of interest to citizens and businesses across Texas. What’s more, it is a question that divided judges on this court. As reflected in our competing concurring opinions, different judges on this court have disagreed about whether the district court correctly interpreted the Texas Sales Representative Act (“TSRA”). But we all agreed that reasonable minds could differ. So rather than provide a partial answer—binding only litigants who file in federal court, not those in state court— we instead certified the question to the Supreme Court of Texas, which can speak with authority for all litigants, in state and federal court alike. We now have that answer, and accordingly affirm in part and reverse and remand in part.” JCB Inc. v. Horsburgh & Scott Co., No. 17-51023 (Oct. 17, 2019).

The Fifth Circuit will not ordinarily grant a writ of mandamus about the erroneous denial of a motion to dismiss for lack of subject matter jurisdiction. But in In re Gee, a sweeping challenge to Louisiana’s abortion laws, the Court observed:

The Fifth Circuit will not ordinarily grant a writ of mandamus about the erroneous denial of a motion to dismiss for lack of subject matter jurisdiction. But in In re Gee, a sweeping challenge to Louisiana’s abortion laws, the Court observed:

“Here, the combination of five federalism concerns makes this a special circumstance and distinguishes it from an ordinary case: (1) A sovereign State is requesting the writ; (2) Plaintiffs seek sweeping review of an entire body of state law; (3) Plaintiffs seek structural injunctions that would give the district court de facto control of state law; (4) the type of discovery waiting on the other side of Louisiana’s motion to dismiss is categorically different than what awaits an ordinary civil litigant; and (5) the ordinary civil litigant cannot demand attorneys’ fees from the State’s taxpayers.”

The Court declined to grant the writ at this stage and after its detailed analysis of the relevant issues, observing

“. . . two reasons. First, it’s not clear from the district court’s order how it would resolve the State’s jurisdictional challenge. And second, much of the State’s argument in its mandamus petition goes beyond jurisdiction. In particular, the State argues that Plaintiffs’ “cumulative-effects challenge” is not cognizable. But that challenge might change after the district court conducts its claim-by-claim analysis of Plaintiffs’ standing. So in our view, resolution of whether that challenge is cognizable should await the district court’s jurisdictional analysis.”

No. 19-30353 (Oct. 18, 2019).

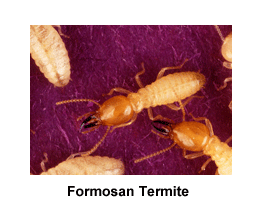

The Cenacs sued Orkin after Formosan termites damaged their house. Based largely on the contract documents, the Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for Orkin, with the exception of the Cenacs’ negligence claim:

The Cenacs sued Orkin after Formosan termites damaged their house. Based largely on the contract documents, the Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for Orkin, with the exception of the Cenacs’ negligence claim:

None of the contracts between the Cenacs and Orkin—the 1991 Agreement, the CPP, or the SSA—required Orkin to recommend, instruct, or direct its customers on how to remedy conditions conducive to termite infestation. . . . Under these circumstances, the Cenacs’ claim that Orkin recommended installation of a vapor barrier and approved its allegedly negligent installation does not involve the breach of a specific contractual duty. Rather, Orkin undertook the task of recommending and directing installation of a vapor barrier, which . . . it had no obligation to do under its contracts with the Cenacs.

Cenac v. Orkin LLC, No. 18-31121 (Oct. 18, 2019).

The EPA approved Louisiana’s plan for controlling haze; both environmental and industry groups protested. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the EPA’s approval under the “arbitrary and capricious” standard of review.

The EPA approved Louisiana’s plan for controlling haze; both environmental and industry groups protested. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the EPA’s approval under the “arbitrary and capricious” standard of review.

As to industry: “We afford ‘significant deference’ to agency decisions involving analysis of scientific data within the agency’s technical expertise. The EPA’s selection of a model to measure air pollution levels is precisely that type of decision. The EPA therefore did not act arbitrarily and capriciously in relying on the CALPUFF model to approve Louisiana’s [statutorily-required] determinations.”

As to environmental groups: “Louisiana’s explanation of its . . . determination . . . omitted two of the five mandatory factors and failed to compare—or even set out—the numbers for the costs and benefits of the control options Louisiana considered. Louisiana also failed to explain how its decision accounted for the EPA-submitted analyses that pointed out substantial flaws in other analyses in the administrative record. But applying the deferential standards of the Administrative Procedures Act to the facts of this case, we hold that the EPA’s approval of Louisiana’s [plan] was not arbitrary and capricious.” Sierra Club v. EPA, No. 18-60116 (Oct. 3, 2019).

Walker and Ameriprise Financial, pursuant to their agreement, arbitrated their dispute under FINRA rules. Walker argued that the panel “exceeded its powers,” and thus fell within a statutory ground for vacatur of the arbitration award. The Fifth Circuit disagreed: “’An arbitrator exceeds his powers [under § 10(a)(4)] if he acts contrary to express contractual provisions.’ Walker does not argue that the panel violated any express provisions of the arbitration agreement, but only that it incorrectly applied [FINRA] Rule 13504.” Walker v. Ameriprise Fin. Servcs., Inc., No. 18-11641 (Oct. 9, 2019) (unpublished).

Walker and Ameriprise Financial, pursuant to their agreement, arbitrated their dispute under FINRA rules. Walker argued that the panel “exceeded its powers,” and thus fell within a statutory ground for vacatur of the arbitration award. The Fifth Circuit disagreed: “’An arbitrator exceeds his powers [under § 10(a)(4)] if he acts contrary to express contractual provisions.’ Walker does not argue that the panel violated any express provisions of the arbitration agreement, but only that it incorrectly applied [FINRA] Rule 13504.” Walker v. Ameriprise Fin. Servcs., Inc., No. 18-11641 (Oct. 9, 2019) (unpublished).

After an unsuccessful detour to the High Court of the Republic of the Marshall Islands, a plaintiff tried to appeal an award from the Western District of Texas of $26,726 in costs under Fed. R. Civ. P. 41(d) (“Costs of a Previously Dismissed Action”), along with a related order that administratively closed the Texas matter until the costs were paid. The Fifth Circuit found it had no jurisdiction because: (1) administrative closure is not a final judgment; (2) the collateral-order doctrine did not apply, “[s]ince there is no indication that the ordered costs could not be paid and later recovered upon a successful appeal of a final judgment,” and (3) mandamus was not available, especially when: “[A]ppellants here do not allege that they are unable to pay. Unwillingness to pay based on disagreement with the district court’s decision is insufficient. Appellants can obtain relief through direct appeal after a final judgment.” Sammons v. Economou, No. 18-50932 (Oct. 10, 2019).

After an unsuccessful detour to the High Court of the Republic of the Marshall Islands, a plaintiff tried to appeal an award from the Western District of Texas of $26,726 in costs under Fed. R. Civ. P. 41(d) (“Costs of a Previously Dismissed Action”), along with a related order that administratively closed the Texas matter until the costs were paid. The Fifth Circuit found it had no jurisdiction because: (1) administrative closure is not a final judgment; (2) the collateral-order doctrine did not apply, “[s]ince there is no indication that the ordered costs could not be paid and later recovered upon a successful appeal of a final judgment,” and (3) mandamus was not available, especially when: “[A]ppellants here do not allege that they are unable to pay. Unwillingness to pay based on disagreement with the district court’s decision is insufficient. Appellants can obtain relief through direct appeal after a final judgment.” Sammons v. Economou, No. 18-50932 (Oct. 10, 2019).

A substantial body of law, focused on the requirements of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, defines the appropriate level of specificity for a plaintiff’s complaint. Pleading specificity can interact with other bodies of law as well, such as insurance coverage, where additional detail can affect an “eight-corners” analysis of whether the allegations fall within coverage. Another illustrative, if infrequent, situation appeared in the FCA case of United States ex rel. Hendrickson v. Bank of America, N.A., where a plaintiff’s lack of detail fed into the defendants’ defense of public disclosure: “Not disputing that the six documents constituted public disclosures, Hendrickson claims they do not disclose substantially the same allegations as his complaint because they do not reference DNEs or name specific banks. The banks respond that the documents’ disclosures are as specific as the complaint, which fails to allege particular instances of their receiving DNEs or differentiate allegations made against each defendant.” No. 18-11472 (Oct. 7, 2019).

A substantial body of law, focused on the requirements of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, defines the appropriate level of specificity for a plaintiff’s complaint. Pleading specificity can interact with other bodies of law as well, such as insurance coverage, where additional detail can affect an “eight-corners” analysis of whether the allegations fall within coverage. Another illustrative, if infrequent, situation appeared in the FCA case of United States ex rel. Hendrickson v. Bank of America, N.A., where a plaintiff’s lack of detail fed into the defendants’ defense of public disclosure: “Not disputing that the six documents constituted public disclosures, Hendrickson claims they do not disclose substantially the same allegations as his complaint because they do not reference DNEs or name specific banks. The banks respond that the documents’ disclosures are as specific as the complaint, which fails to allege particular instances of their receiving DNEs or differentiate allegations made against each defendant.” No. 18-11472 (Oct. 7, 2019).