On pages 62-63 of the May 2020 issue of “D CEO” magazine, you can read a profile of me as the only Tarot-reading lawyer in Dallas–a skill first acquired on trips to New Orleans for appellate business!

On pages 62-63 of the May 2020 issue of “D CEO” magazine, you can read a profile of me as the only Tarot-reading lawyer in Dallas–a skill first acquired on trips to New Orleans for appellate business!

Related to the Fifth Circuit’s recent general reminder in Sun Coast Resources v. Conrad about when oral argument will occur, Chief Judge Owens’s April 20 Covid-19 order makes clear that individual panels may decide when to use “Zoom” or other such conferencing technology. H/T to Louisiana’s Ray Ward for drawing my attention to this order.

Related to the Fifth Circuit’s recent general reminder in Sun Coast Resources v. Conrad about when oral argument will occur, Chief Judge Owens’s April 20 Covid-19 order makes clear that individual panels may decide when to use “Zoom” or other such conferencing technology. H/T to Louisiana’s Ray Ward for drawing my attention to this order.

Realogy Holdings Corp. v. Jongeblood offers several practical tips about litigating a noncompetition agreement:

Realogy Holdings Corp. v. Jongeblood offers several practical tips about litigating a noncompetition agreement:

- Oral findings of fact at the hearing can satisfy the requirements of Fed. R. Civ. P. 52, when the “oral findings together with [the] written order nonetheless give us ‘a clear understanding of the factual basis for the decision'”;

- Testimony about confidential information given to the employee established the Texas-law requirements about adequate consideration for a noncompete, even when the employer did not make an express promise to do so at the time of contracting; abd

- After an unsuccessful appellate challenge to a preliminary injunction that enforces a noncompete, it can be appropriate to ask the trial court to “when determining the term of any injunction, to reweigh the equities . . . in light of the time that has passed during the pendency of th[e] appeal.”

No. 19-20864 (April 27, 2020).

The Fifth Circuit allowed a “John Doe” summons to proceed, requiring a law firm to disclose certain client entities. After reviewing authority nationwide about such warrants, the Court concluded: “[D]isclosure of the Does’ identities would inform the IRS that the Does participated in at least one of the numerous transactions described in the John Doe summons issued to the Firm, but ‘[i]t is less than clear . . . as to what motive, or other confidential communication of [legal] advice, can be inferred from that information alone.’ Consequently, the Firm’s clients’ identities are not ‘connected inextricably with a privileged communication,’ and, therefore, the ‘narrow exception’ to the general rule that client identities are not protected by the attorney-client privilege is inapplicable.” Taylor Lohmeyer Law Firm PLLC v. United States, No. 19-50506 (April 24, 2020).

The Fifth Circuit allowed a “John Doe” summons to proceed, requiring a law firm to disclose certain client entities. After reviewing authority nationwide about such warrants, the Court concluded: “[D]isclosure of the Does’ identities would inform the IRS that the Does participated in at least one of the numerous transactions described in the John Doe summons issued to the Firm, but ‘[i]t is less than clear . . . as to what motive, or other confidential communication of [legal] advice, can be inferred from that information alone.’ Consequently, the Firm’s clients’ identities are not ‘connected inextricably with a privileged communication,’ and, therefore, the ‘narrow exception’ to the general rule that client identities are not protected by the attorney-client privilege is inapplicable.” Taylor Lohmeyer Law Firm PLLC v. United States, No. 19-50506 (April 24, 2020).

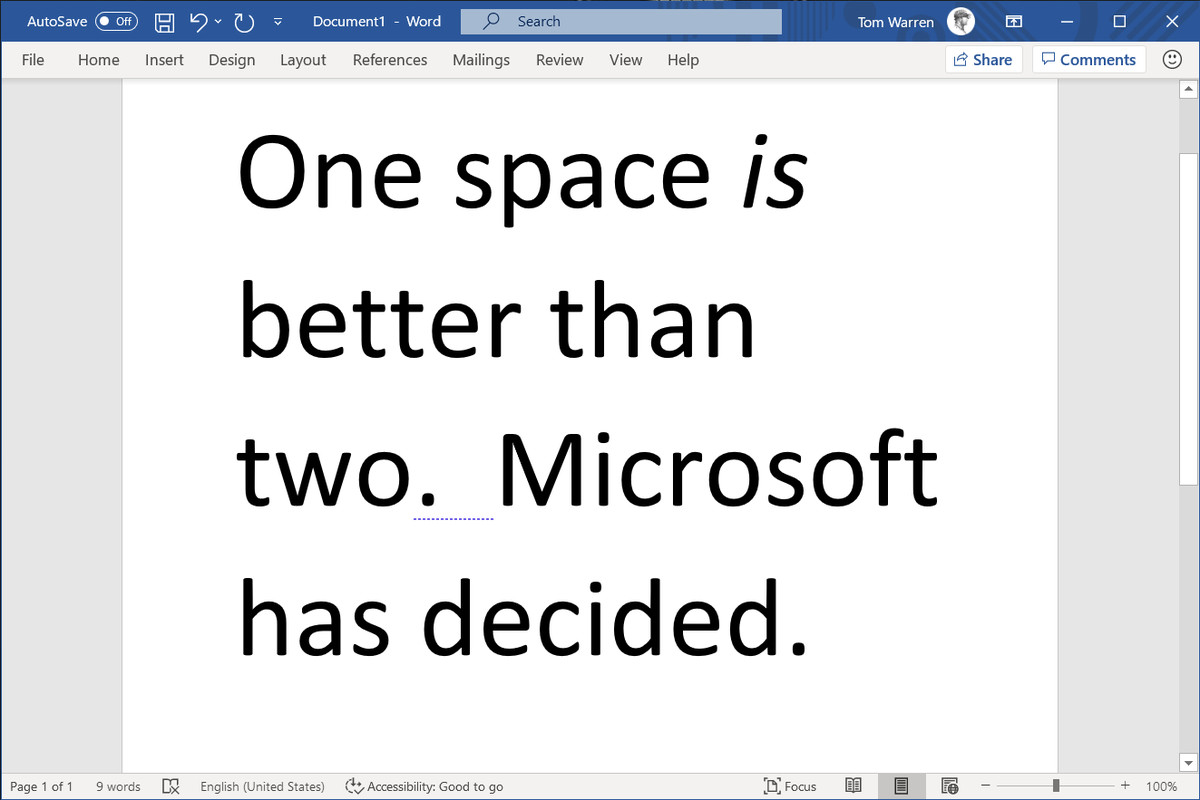

As reported by The Verge on April 24, Microsoft Word now auto-corrects the use of two spaces after a period at the end of a sentence. The battle, such as it was, should now be considered over. This influential article in Slate explains why the one-spacers – while correct during the era of typewriters, which made every letter and space the same size – have been wrong since the early 1990s and the widespread availability of proportional spacing in modern word processing software.

As reported by The Verge on April 24, Microsoft Word now auto-corrects the use of two spaces after a period at the end of a sentence. The battle, such as it was, should now be considered over. This influential article in Slate explains why the one-spacers – while correct during the era of typewriters, which made every letter and space the same size – have been wrong since the early 1990s and the widespread availability of proportional spacing in modern word processing software.

In Jacked Up LLC v. Sara Lee Corp., the plaintiff’s expert “seems to have assumed

that the projections in the Sara Lee Pro Forma were correct and then extrapolated lost-profits figures.” But the record also contained a detailed explanation by the defendant’s marketing director about why “the assumptions in the pro formas are merely

elaborate guesswork by the business and sales teams” until there are actual product sales. Accordingly, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the exclusion of the expert under a basic Daubert principle: “Expert evidence that is not ‘reliable at each and every step’ is not admissible.” No. 19-10391 (April 3, 2020) (unpublished). (citation omitted). (LPHS represented the successful appellee in this case.)

The relator in United States ex rel Porter v. Magnolia Health Plan “allege[d] that her former employer, which contracts with the Mississippi Division of Medicaid, is violating the False Claims Act by using licensed professional nurses for tasks that require the expertise of registered nurses.” The Fifth Circuit affirmed dismissal: “Plaintiff-Appellant’s first amended complaint makes no specific allegations regarding the materiality of Magnolia’s alleged fraud. The contracts between Magnolia and MississippiCAN do not require Magnolia to staff care or case manager positions with registered nurses, and they contain only broad, boilerplate language requiring Magnolia to follow all laws.” No. 18-60746 (April 15, 2020) (unpublished).

Sun Coast Resources Inc. v. Conrad, No. 19-20058 (April 16, 2020), involved a challenge to an arbitration award. The challenging party did not agree with the Fifth Circuit’s decision to proceed without oral argument, and filed a motion seeking an oral argument. It was denied and the Court’s explanation is instructive:

Sun Coast Resources Inc. v. Conrad, No. 19-20058 (April 16, 2020), involved a challenge to an arbitration award. The challenging party did not agree with the Fifth Circuit’s decision to proceed without oral argument, and filed a motion seeking an oral argument. It was denied and the Court’s explanation is instructive:

- “Sun Coast’s motion misunderstands the federal appellate process in

more ways than one. To begin, the motion claims that ‘oral argument is the

norm rather than the exception.’ Not true. ‘More than 80 percent of federal

appeals are decided solely on the basis of written briefs. Less than a quarter

of all appeals are decided following oral argument.'”; - “Sun Coast suggests that deciding this case without oral argument would be ‘akin to . . . cafeteria justice.’ The Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure state otherwise. They authorize “a panel of three judges who have examined the briefs and record” to ‘unanimously agree[] that oral argument is unnecessary for any of the following reasons”—such as the fact that “the dispositive issue or issues have been authoritatively decided,” or that “the facts and legal arguments are adequately presented in the briefs and record, and the decisional process would not be significantly aided by oral argument.””; and

- “[A]nother tactic powerful economic interests sometimes use against

the less resourced is to increase litigation costs in an attempt to bully the

opposing party into submission by war of attrition—for example, by filing a

meritless appeal of an arbitration award won by the economically weaker

party, and then maximizing the expense of litigating that appeal. Dispensing with oral argument where the panel unanimously agrees it is unnecessary, and where the case for affirmance is so clear, is not cafeteria justice—it is simply justice.” (citations omitted and emphasis added in all the above quotes).

The fast-paced litigation about access to abortion during the COVID-19 pandemic produced a strong statement about government power (including the power of the administrative state) during a health crisis: “The bottom line is this: when faced with a society-threatening epidemic, a state may implement emergency measures that curtail constitutional rights so long as the measures have at least some ‘real or substantial relation’ to the public health crisis and are not ‘beyond all question, a plain, palpable invasion of rights secured by the fundamental law.'” In re Abbott, No. 20-50264 (April 7, 2020) (orig. proceeding) (quoting Jacobson v. Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11 (1905)). The opinion has gathered national coverage from diverse media outlets such as CNN and Reason.

The fast-paced litigation about access to abortion during the COVID-19 pandemic produced a strong statement about government power (including the power of the administrative state) during a health crisis: “The bottom line is this: when faced with a society-threatening epidemic, a state may implement emergency measures that curtail constitutional rights so long as the measures have at least some ‘real or substantial relation’ to the public health crisis and are not ‘beyond all question, a plain, palpable invasion of rights secured by the fundamental law.'” In re Abbott, No. 20-50264 (April 7, 2020) (orig. proceeding) (quoting Jacobson v. Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11 (1905)). The opinion has gathered national coverage from diverse media outlets such as CNN and Reason.

Third of three posts this week about Illinois Tool Works v. Rust-Oleum; in addition to reversing two damages awards, the Fifth Circuit reversed a finding of Lanham Act liability for a lack of evidence about materiality. Citing prior Circuit precedent, the Court held: “If misleading claims about something as vital to pizza as its ingredients were not necessarily material, a misleading claim about how long a windshield water-repellant treatment lasts was not, either. Moreover, though Illinois Tool Works asserts that consumers want to know how long these products last, it does not substantiate this assertion with evidence. So this argument fails.” No.19-20210 (April 9, 2020).

The Fifth Circuit’s recent opinion in Illinois Tool Works v. Rust-Oleum, also rejected the plaintiff’s award of damages for corrective advertising, holding:

The Fifth Circuit’s recent opinion in Illinois Tool Works v. Rust-Oleum, also rejected the plaintiff’s award of damages for corrective advertising, holding:

“Illinois Tool Works has never even asserted that it plans to run corrective advertising. It did not say what the advertising might consist of, offer a ballpark figure of what it might cost, or provide even a rough methodology for the jury to estimate the cost. Damages need not be proven with exacting precision, but they cannot be based on pure speculation. . . . Illinois Tool Works . . . argues that it was not required to show that it ‘needs’ the award, and that its 40 years of goodwill and tens of millions of dollars spent on advertising, coupled with RustOleum’s expenditures, support the unremitted amount. . . . [I]t does not explain how its decades of goodwill and past advertising expenditures show a loss or justify compensation in any amount. These bald facts lack inherent explanatory value. So these arguments fail.”

No. 19-20210 (April 9, 2020).

Illinois Tool Works proved at trial that Rust-Oleum engaged in false advertising about the parties’ competing water-repellent products. The Fifth Circuit reversed the judgment as to disgorgement (among other matters), reasoning:

Illinois Tool Works proved at trial that Rust-Oleum engaged in false advertising about the parties’ competing water-repellent products. The Fifth Circuit reversed the judgment as to disgorgement (among other matters), reasoning:

“Illinois Tool Works failed to present sufficient evidence of attribution. It cites nothing that links Rust-Oleum’s false advertising to its profits, that permits a reasonable inference that the false advertising generated profits, or that shows that even a single consumer purchased RainBrella because of the false advertising.

Illinois Tool Works argues, however, that three things show that RustOleum benefitted from its false advertising: witnesses testified about how important the advertising claims were to Rust-Oleum, tens of thousands of people saw the commercial, and RainBrella was placed on nearby shelves in the same stores as Rain-X. None of this shows attribution.” Illinois Tool Works v. Rust-Oleum, No. 19-20210 (April 9, 2020).

I n Golden Spread Electric Co-op v. Emerson Process Management, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of business-tort claims under Texas’s economic loss rule.

n Golden Spread Electric Co-op v. Emerson Process Management, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of business-tort claims under Texas’s economic loss rule.

Golden Spread, a public utility, contracted with Emerson to provide “a new, customized control system” for a steam turbine generator. During testing of the new system, the software installed by Emerson issued a mistaken command that caused the turbine to overheat and become damaged.

The Fifth Circuit reviewed Golden Spread’s claims in light of two policy considerations identified by Texas cases in the area. First, “[p]urely economic harms proliferate widely and are not self-limiting in the way that physical damage is ….” Second, “the risk of economic harms are better suited to allocation by contract” because the parties “usually have a full opportunity” to negotiate such risks before finalizing a contract.

The Court’s reasoning may prove relevant to future lawsuits involving business issues arising from the current COVID-19 crisis.

Feeling salty about the handling of a AAA arbitration, Texas Brine (not a Louisiana citizen) sued the AAA (not a Louisiana citizen) and two Louisiana-based arbitrators in New Orleans state court. The AAA was served with process and immediately removed the case, before the two Louisiana citizens were served.

Feeling salty about the handling of a AAA arbitration, Texas Brine (not a Louisiana citizen) sued the AAA (not a Louisiana citizen) and two Louisiana-based arbitrators in New Orleans state court. The AAA was served with process and immediately removed the case, before the two Louisiana citizens were served.

The Fifth Circuit held that such a “snap removal” was permitted by the plain text of the removal statute, noting that the “forum defendant rule” only applied once an in-state defendant was served. (In relevant part, 28 U.S.C. § 1441(b)(2) says that a civil action “. . . may not be removed if any of the parties in interest properly joined and served as defendants is a citizen of the State in which such action is brought.” (emphasis added)).

The Court declined to find that this situation produced an “absurd result,” noting the Second Circuit’s observation that: “Congress may well have adopted the ‘properly joined and served’ requirement in an attempt to both limit gamesmanship and provide a bright-line rule keyed on service, which is clearly more easily administered than a fact-specific inquiry into a plaintiff’s intent or opportunity to actually serve a home-state defendant.” Texas Brine Co. LLC v. AAA, No. 18-31184 (April 7, 2020).

The arbitration clause in Bowles’s employment contract had a provision delegating to the arbitrator, “any legal dispute . . . arising out of, relating to, or concerning the validity, enforceability or breach of this Agreement, shall be resolved by final and binding arbitration.” Bowles argued that disparity of bargaining power during her contract negotiations amounted to procedural unconscionability. “Bowles’s challenge to the Arbitration Agreement as procedurally unconscionable was a challenge to the Agreement’s enforceability, not to its existence. For that reason, under the delegation clause in the Agreement that sends all enforcement challenges to an arbitrator, the district court correctly referred this challenge to the arbitrator.” Bowles v. OneMain Fin. Group, No. 18-60749 (April 2, 2020).

“For a generation, the State of Texas and a federally recognized Indian tribe, the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, have litigated the Pueblo’s attempts to conduct various gaming activities on its reservation near El Paso. This latest case poses familiar questions that yield familiar answers: (1) which federal law governs the legality of the Pueblo’s gaming operations—the Restoration Act (which bars gaming that violates Texas law) or the more permissive Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (which “establish[es] . . . Federal standards for gaming on Indian lands”); and (2) whether the district court correctly enjoined the Pueblo’s gaming operations.” Unfortunately for the tribe, the Fifth Circuit found that a previous opinion conclusively settled these issues in favor of the State of Texas. The opinion also discusses the proper scope of injunctive relief for such a situation. Texas v. Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, No. 19-50400 (April 2, 2020).

“For a generation, the State of Texas and a federally recognized Indian tribe, the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, have litigated the Pueblo’s attempts to conduct various gaming activities on its reservation near El Paso. This latest case poses familiar questions that yield familiar answers: (1) which federal law governs the legality of the Pueblo’s gaming operations—the Restoration Act (which bars gaming that violates Texas law) or the more permissive Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (which “establish[es] . . . Federal standards for gaming on Indian lands”); and (2) whether the district court correctly enjoined the Pueblo’s gaming operations.” Unfortunately for the tribe, the Fifth Circuit found that a previous opinion conclusively settled these issues in favor of the State of Texas. The opinion also discusses the proper scope of injunctive relief for such a situation. Texas v. Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, No. 19-50400 (April 2, 2020).

A union protested that an arbitrator, in the guise of correcting a “technical” error with his original award, in fact revised its substance in a way contrary to the applicable arbitration rules. The Fifth Circuit disagreed: “To the contrary, he cited [AAA] Rule 40, classified his error as a “technical” one capable of correction, and held that his correction did not violate Rule 40, notwithstanding the Union’s argument that he was “redetermin[ing] the merits” of CWA’s claim against the Company. Even if the arbitrator made a mistake in reaching his conclusion, “[t]he potential for . . . mistakes is the price of agreeing to arbitration. . . . The arbitrator’s construction holds, however good, bad, or ugly.” Communication Workers of America v. Southwestern Bell, No. 19-50686 (March 27, 2020) (citations omitted).

A union protested that an arbitrator, in the guise of correcting a “technical” error with his original award, in fact revised its substance in a way contrary to the applicable arbitration rules. The Fifth Circuit disagreed: “To the contrary, he cited [AAA] Rule 40, classified his error as a “technical” one capable of correction, and held that his correction did not violate Rule 40, notwithstanding the Union’s argument that he was “redetermin[ing] the merits” of CWA’s claim against the Company. Even if the arbitrator made a mistake in reaching his conclusion, “[t]he potential for . . . mistakes is the price of agreeing to arbitration. . . . The arbitrator’s construction holds, however good, bad, or ugly.” Communication Workers of America v. Southwestern Bell, No. 19-50686 (March 27, 2020) (citations omitted).

In Bradley v. Ackal, the Fifth Circuit reversed the sealing of an on-the-record proceeding involving the settlement of a minor’s claim connected to a police shooting. The Court reminded: “’In exercising its discretion to seal judicial records, the court must balance the public’s common law right of access against the interests favoring nondisclosure.’ But, ‘[t]he presumption however gauged in favor of public access to judicial records[]’ [is] one of the interests to be weighed on the [public’s] “side of the scales.”‘ No. 18-31052 (March 23, 2020) (citations omitted).

An unsuccessful motion to compel arbitration did not fare better on appeal when:

- The question of who decides arbitrability was not raised in the motion (and was thus forfeited for appeal purposes);

- Equitable estoppel was briefed in the motion with reference to authority about “concerted misconduct estoppel” – theory rejected by the Texas Supreme Court;

- Direct benefits estoppel was unavailable because the plaintiffs sued under federal employment law, not their state-law employment agreements;

- Third party beneficiary status was not available because the movant was not named in the agreement, while the entity that actually had hired the plaintiffs was.

Hiser v. NZone Guidance LLC, No. 19-50353 (March 24, 2020) (unpublished).

The appellant in North Cypress Medical Center Operating Co. v. Cigna Healthcare argued that the district court failed to follow the law of the case as established by an earlier Fifth Circuit panel, citing a paragraph in the panel’s opinion that described the two-step process for resolving a particular ERISA issue. The Fifth Circuit disagreed: “This general statement of the law, expressed in terms of the facts of the case, is no mandate at all. Nor is it a statement of the whole law regarding review of ERISA benefit decisions. The court’s summary omits mention of [two key cases], in which this court established that a party may skip the legal correctness inquiry and proceed to consider

whether the plan administrator abused its discretion, as outlined in [the prior panel opinion]. The [prior] panel did not deny the authority of [those cases] (nor could it).

Accordingly, the district court properly relied on [those cases] in skipping the legal correctness analysis. In so doing, the court did not violate the law of the case and committed no error.” No. 18-20576 (March 18, 2020).

DISH Network declared an impasse after lengthy negotiations with the Communication Workers of America. The NLRB rejected that declaration; the Fifth Circuit reversed the NLRB’s factual determination: “The Board’s decision rested on its determination that the Union’s November 2014 counterproposal was a ‘white flag’ of surrender. But the ‘white flag’ characterization in turn rested on an unsound factual foundation from the ALJ” about how unionized employees reacted to a particular compensation system as compared to nonunionized ones. DISH Network Corp. v. NLRB (revised March 24, 2020).

DISH Network declared an impasse after lengthy negotiations with the Communication Workers of America. The NLRB rejected that declaration; the Fifth Circuit reversed the NLRB’s factual determination: “The Board’s decision rested on its determination that the Union’s November 2014 counterproposal was a ‘white flag’ of surrender. But the ‘white flag’ characterization in turn rested on an unsound factual foundation from the ALJ” about how unionized employees reacted to a particular compensation system as compared to nonunionized ones. DISH Network Corp. v. NLRB (revised March 24, 2020).

A Houston-based engineering firm negotiated a contract with a New Jersey town. The town then sought to avoid paying, arguing that no contract had been formed because it had not obtained proper approvals as required by New Jersey’s statutes about public contracts. The firm countered that the parties’ agreement had a Texas choice-of-law provision, which should also control as to contract formation. Noting that while this dispute seemed to form a “chicken-or-the-egg problem,” the Fifth Circuit ruled for the town as “the choice-of-law provision has force only if the parties validly formed a contract.” It remanded for consideration of potential quantum meruit liability. EHRA Engineering v. Downe Township, No. 19-20176 (March 19, 2020).

A Houston-based engineering firm negotiated a contract with a New Jersey town. The town then sought to avoid paying, arguing that no contract had been formed because it had not obtained proper approvals as required by New Jersey’s statutes about public contracts. The firm countered that the parties’ agreement had a Texas choice-of-law provision, which should also control as to contract formation. Noting that while this dispute seemed to form a “chicken-or-the-egg problem,” the Fifth Circuit ruled for the town as “the choice-of-law provision has force only if the parties validly formed a contract.” It remanded for consideration of potential quantum meruit liability. EHRA Engineering v. Downe Township, No. 19-20176 (March 19, 2020).

Surprising no one, the constitutional challenge to the CFPB’s structure presented by CFPB v. All American Check Cashing will be reviewed en banc by the full Fifth Circuit.

Surprising no one, the constitutional challenge to the CFPB’s structure presented by CFPB v. All American Check Cashing will be reviewed en banc by the full Fifth Circuit.

This is a cross-post from 600Commerce, which follows the Dallas Court of Appeals.

One Dallas Court of Appeals case addresses the breach-of-contract defense of impracticability, Hewitt v Biscaro, 353 S.W.3d 304 (Tex. App.—Dallas 2011, no pet.). Relevant to the current crisis, it involves a government order that allegedly made performance more difficult. The Court examined whether:

One Dallas Court of Appeals case addresses the breach-of-contract defense of impracticability, Hewitt v Biscaro, 353 S.W.3d 304 (Tex. App.—Dallas 2011, no pet.). Relevant to the current crisis, it involves a government order that allegedly made performance more difficult. The Court examined whether:

- the performance issue was a basic assumption of the contract;

- the government’s action was an official order or regulation (in that case, the SEC’s contact with the defendant was not); and

- the defendant was acting in good faith.

The Court relied on an earlier Texas Supreme Court case and the relevant Restatement (Second) of Contracts provision. Application of this opinion will be important in upcoming commercial disputes created by the novel coronavirus.

This is a cross-post from 600Hemphill, which follows the Texas Supreme Court:

This is a cross-post from 600Hemphill, which follows the Texas Supreme Court:

Henry McCall lived in a cabin on Homer Hillis’s property, occasionally helping Hillis with maintenance at the McCall’s bed-and-breakfast. While working on Hillis’s sink, a brown recluse spider bit McCall. The Texas Supreme Court found that  the ferae naturae doctrine barred McCall’s lawsuit against Hillis: “[H]e owed no duty to the invitee because he was unaware of the presence of brown recluse spiders on his property and he neither attracted the offending spider to his property nor reduced it to his possession. Further, [McCall] had actual knowledge of the presence of spiders on the property.” Hillis v. McCall, No. 18-1065 (Tex. March 13, 2020). In addition to its impact on brown-recluse litigation, the reasoning of this opinion about liability for small, dangerous creatures well be relevant in any future litigation about coronavirus exposure.

the ferae naturae doctrine barred McCall’s lawsuit against Hillis: “[H]e owed no duty to the invitee because he was unaware of the presence of brown recluse spiders on his property and he neither attracted the offending spider to his property nor reduced it to his possession. Further, [McCall] had actual knowledge of the presence of spiders on the property.” Hillis v. McCall, No. 18-1065 (Tex. March 13, 2020). In addition to its impact on brown-recluse litigation, the reasoning of this opinion about liability for small, dangerous creatures well be relevant in any future litigation about coronavirus exposure.

Rogers, a collection agency, wrote Salinas, stating the amount due ($4629.96)

and the interest and fees due ($0.00). The letter also said: “In the event there is interest or other charges accruing on your account, the amount due may be greater than the  amount shown above after the date of this notice.”

amount shown above after the date of this notice.”

The Fifth Circuit held that, while its precedent had not squarely addressed “conditional” language such as “in the event,” Rogers’s letter was not deceptive. “Salinas reads it to imply the possibility that interest or other charges may accrue when in fact they cannot,” noted the Court, but “[a]n illustration shows the problem with Salinas’ reading of the letter”:

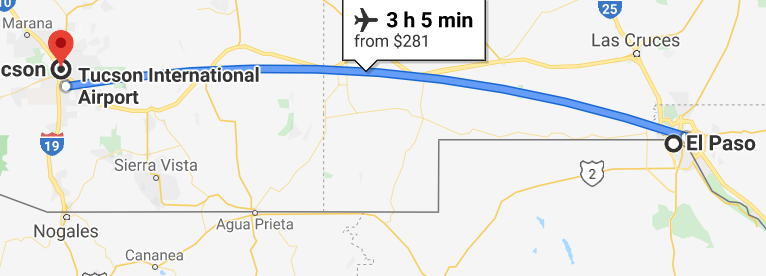

Suppose a traveler boards a flight from El Paso, TX, to Tucson, AZ—a route traversing only desert—and is shown a safety video describing steps to take “in the event of a water landing.” Even the least sophisticated traveler would not take the video to imply the plane would be flying over water. No passenger would leap out of his seat in panic, concluding he had boarded the wrong flight. Even a traveler “tied to the very last rung on the intelligence or sophistication ladder” would interpret the video as merely acknowledging the reality that some flights, if not this one, fly over water.

Salinas v. R.A. Rogers Inc., No. 19-50618 (March 12, 2020).

Casalicchio received a pre-foreclosure notice that “contained a deadline thirty days from the day the notice was printed, even though the deed of trust called for a deadline thirty days from the day the letter was mailed.” (emphasis in original). Unfortunately for Casalicchio, while the Fifth Circuit acknowledged older Texas cases that refer to an “absolute” right to “strict compliance” with a deed of trust, the Court concluded: “Since the 1980s, the Texas Supreme Court has repeatedly moderated its rule that the ‘terms of a deed of trust must be strictly followed,’ clarifying recently that harmless mistakes do not void otherwise-valid foreclosure sales.” The defect in his notice was thus “but a ‘minor defect,’ insufficiently prejudicial to justify setting aside an otherwise valid foreclosure sale.” Casalacchio v. BOKF, N.A., No. 19-20246 (March 6, 2020) (applying, inter alia, Hemyari v. Stephens, 355 S.W.3d 623 (Tex. 2011)).

Casalicchio received a pre-foreclosure notice that “contained a deadline thirty days from the day the notice was printed, even though the deed of trust called for a deadline thirty days from the day the letter was mailed.” (emphasis in original). Unfortunately for Casalicchio, while the Fifth Circuit acknowledged older Texas cases that refer to an “absolute” right to “strict compliance” with a deed of trust, the Court concluded: “Since the 1980s, the Texas Supreme Court has repeatedly moderated its rule that the ‘terms of a deed of trust must be strictly followed,’ clarifying recently that harmless mistakes do not void otherwise-valid foreclosure sales.” The defect in his notice was thus “but a ‘minor defect,’ insufficiently prejudicial to justify setting aside an otherwise valid foreclosure sale.” Casalacchio v. BOKF, N.A., No. 19-20246 (March 6, 2020) (applying, inter alia, Hemyari v. Stephens, 355 S.W.3d 623 (Tex. 2011)).

What is a “sole, superseding cause”? BP Exploration v. Claimaint ID 100191715 did not resolve the question, but found an argument sufficiently credible to require a remand for further review in the Deepwater Horizon claims process: “BP argues that Claimant passed the V-Shaped Revenue Pattern due solely to a price spike and drop in the price of fertilizer that was unrelated to the oil spill. According to BP, the spike caused Claimant’s revenues to soar and crash back down to normal rates thereafter. And, only because Claimant used months during the price spike as its benchmark period was it able to satisfy the ‘V-Shape Revenue Pattern’ test in Exhibit 4B. In other words, Claimant’s loss was not due to the spill; rather, the price spike in fertilizer was the sole, superseding cause for its loss.” No. 19-30264 (March 3, 2020).

What is a “sole, superseding cause”? BP Exploration v. Claimaint ID 100191715 did not resolve the question, but found an argument sufficiently credible to require a remand for further review in the Deepwater Horizon claims process: “BP argues that Claimant passed the V-Shaped Revenue Pattern due solely to a price spike and drop in the price of fertilizer that was unrelated to the oil spill. According to BP, the spike caused Claimant’s revenues to soar and crash back down to normal rates thereafter. And, only because Claimant used months during the price spike as its benchmark period was it able to satisfy the ‘V-Shape Revenue Pattern’ test in Exhibit 4B. In other words, Claimant’s loss was not due to the spill; rather, the price spike in fertilizer was the sole, superseding cause for its loss.” No. 19-30264 (March 3, 2020).

The ground rules for the administrative state are few, important, and vexingly difficult to apply. The en banc court confronted the structure of Fannie Mae’s regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, in Collins v. Mnuchin, 938 F.3d 553 (5th Cir. 2019), and found it wanting constitutionally. In CFPB v. All American Check Cashing, a panel majority confronted the structure of another Great Recession entity, the Consumer Finance Protection Board, and concluded that “neither the text of the Constitution nor the Supreme Court’s previous decisions support the Appellants’ arguments that the CFPB is unconstitutionally structured.” No. 18-60302 (March 3, 2020).

The ground rules for the administrative state are few, important, and vexingly difficult to apply. The en banc court confronted the structure of Fannie Mae’s regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, in Collins v. Mnuchin, 938 F.3d 553 (5th Cir. 2019), and found it wanting constitutionally. In CFPB v. All American Check Cashing, a panel majority confronted the structure of another Great Recession entity, the Consumer Finance Protection Board, and concluded that “neither the text of the Constitution nor the Supreme Court’s previous decisions support the Appellants’ arguments that the CFPB is unconstitutionally structured.” No. 18-60302 (March 3, 2020).

A concurrence elaborated: “The President can remove the CFPB Director only for ‘inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office,’ a broad standard repeatedly approved by the Supreme Court. That alone is enough to decide this case. If there is any threat of undue concentration of power, the Office of President is its beneficiary.” A dissent faulted the majority’s reasoning and the judicial process employed: “Collins winds up in the dustbin because two judges say it should. At one time, those judges thought it beyond the pale ‘to rely on strength in numbers rather than sound legal principles in order to reach their desired result in [a] specific case.’ Now, they suddenly discover that stare decisis is for suckers.” (footnotes omitted).

A concurrence elaborated: “The President can remove the CFPB Director only for ‘inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office,’ a broad standard repeatedly approved by the Supreme Court. That alone is enough to decide this case. If there is any threat of undue concentration of power, the Office of President is its beneficiary.” A dissent faulted the majority’s reasoning and the judicial process employed: “Collins winds up in the dustbin because two judges say it should. At one time, those judges thought it beyond the pale ‘to rely on strength in numbers rather than sound legal principles in order to reach their desired result in [a] specific case.’ Now, they suddenly discover that stare decisis is for suckers.” (footnotes omitted).

An exceptionally clear example of “virtual representation” for res judicata purposes appears in Butler v. Endeavor Air, Inc., No. 19-20304 (March 4, 2020).

An exceptionally clear example of “virtual representation” for res judicata purposes appears in Butler v. Endeavor Air, Inc., No. 19-20304 (March 4, 2020).

Butler unsuccessfully sued Delta Airlines in state court about difficulties his daughter experienced on a flight. Final judgment was entered for Delta after a partial summary judgment and a jury trial.

Butler also sued Endeavor Airlines–a Delta subsidiary that operated the flight in question. Delta had stipulated, in both cases (it had at one point been named in the second case) that it would accept any liability assigned to Endeavor.

Butler also sued Endeavor Airlines–a Delta subsidiary that operated the flight in question. Delta had stipulated, in both cases (it had at one point been named in the second case) that it would accept any liability assigned to Endeavor.

The district court found the Endeavor suit was barred by res judicata and the Fifth Circuit. Delta was Endeavor’s “virtual representative” in the first action given their parent-subsidiary relationship, the same set of facts involved in both cases, and Delta’s stipulation.

Rules of procedure require precision in pleading a cause of action. The eight-corners rule of insurance coverage, in contrast, often rewards imprecision. A powerful example appears in Allied World Specialty Ins. Co. v. McCathern, PLLC, a duty-to-defend claim arising from a legal malpractice claim, where the Fifth Circuit held: “The allegations that McCathern did not monitor the file, conduct legal research, or communicate with the client are factual assertions—as opposed to causes of action—even if they are vague. Allied World’s challenge to the factual allegations thus seems to be that they are not specific enough or may not prove true. But at the duty-to-defend stage it is not for us to say whether West Star will be able to prove that McCathern was negligent in failing to monitor the personal injury suit or in failing to research legal issues.” No. 17-10615 (Feb. 26, 2020, unpublished).

Rules of procedure require precision in pleading a cause of action. The eight-corners rule of insurance coverage, in contrast, often rewards imprecision. A powerful example appears in Allied World Specialty Ins. Co. v. McCathern, PLLC, a duty-to-defend claim arising from a legal malpractice claim, where the Fifth Circuit held: “The allegations that McCathern did not monitor the file, conduct legal research, or communicate with the client are factual assertions—as opposed to causes of action—even if they are vague. Allied World’s challenge to the factual allegations thus seems to be that they are not specific enough or may not prove true. But at the duty-to-defend stage it is not for us to say whether West Star will be able to prove that McCathern was negligent in failing to monitor the personal injury suit or in failing to research legal issues.” No. 17-10615 (Feb. 26, 2020, unpublished).

J&J Sports v. Enola Investments, a dispute about an unauthorized broadcast of the most recent “Fight of the Century” (Mayweather v. Pacquiao in 2015) led to a muddled record as to how the bar in question rebroadcast the fight:

J&J Sports v. Enola Investments, a dispute about an unauthorized broadcast of the most recent “Fight of the Century” (Mayweather v. Pacquiao in 2015) led to a muddled record as to how the bar in question rebroadcast the fight:

“There is conflicting evidence about how the Lounge broadcast the Fight. Small claimed that an employee streamed the Fight over the internet, but J & J’s investigator testified that internet streaming typically results in lower quality video than the high definition broadcast he saw at the Lounge. J & J’s corporate representative also testified that the Fight was not available to commercial establishments via internet streaming. But J & J’s investigator muddled the waters by stating that he did not see cable or satellite equipment at the Lounge. And now, on appeal, defendants claim that the Lounge received the Fight via cable because Enola maintained a business account with Comcast. The only undisputed evidence is that the Fight was originally transmitted via satellite.”

This record required affirmance under the applicable standard: “The district court thus had several plausible options to choose from—satellite, internet, or cable. And when ‘there are two permissible views of the evidence, the fact-finder’s choice between them cannot be clearly erroneous.'” (citations omitted). No. 19-20458 (Feb. 28, 2020, unpublished).

The 2016 Presidential election, one of only five since 1824 when the Electoral College winner lost the popular vote, led to nationwide debate about the College, which in turn led to LULAC v. Abbott – a constitutional challenge to the “Winner Take All” law in Texas that assigns all the state’s electoral votes to the candidate who wins that state’s popular vote. The Fifth Circuit rejected a “one-person, one-vote” challenge to WTA based on a 1969 three-judge opinion that the Supreme Court summarily affirmed, and has not overruled or limited since. It also rejected a challenge based on right-of-association grounds, observing: “[A]ny disadvantage they allege is solely a consequence of their lack of electoral success. But ‘the function of the election process is to winnow out and finally reject all but the chosen candidates.'” No. 19-50214 (Feb. 26, 2020) (citations omitted). (Above, the unfortunate Samuel Tilden, the only Presidential candidate in history to lose despite receiving an outright majority – not just a plurality – of the popular vote).

The 2016 Presidential election, one of only five since 1824 when the Electoral College winner lost the popular vote, led to nationwide debate about the College, which in turn led to LULAC v. Abbott – a constitutional challenge to the “Winner Take All” law in Texas that assigns all the state’s electoral votes to the candidate who wins that state’s popular vote. The Fifth Circuit rejected a “one-person, one-vote” challenge to WTA based on a 1969 three-judge opinion that the Supreme Court summarily affirmed, and has not overruled or limited since. It also rejected a challenge based on right-of-association grounds, observing: “[A]ny disadvantage they allege is solely a consequence of their lack of electoral success. But ‘the function of the election process is to winnow out and finally reject all but the chosen candidates.'” No. 19-50214 (Feb. 26, 2020) (citations omitted). (Above, the unfortunate Samuel Tilden, the only Presidential candidate in history to lose despite receiving an outright majority – not just a plurality – of the popular vote).

Faced with “extraordinarily confused” case law within the Circuit about the federal-officer removal statute (28 USC sec. 1442(a)(1)), the en banc Court’s opinion in Latiolais v. Huntington Ingalls is intended to “strip away the confusion, align with sister circuits, and rely on the plain language of the statute, as broadened in 2011.” The new test requires a defendant to show: “(1) it has asserted a colorable federal defense, (2) it is a ‘person’ within the meaning of the statute, (3) that has acted pursuant to a federal officer’s directions, and (4) the charged conduct is connected or associated with an act pursuant to a federal officer’s directions.” It abandons a previously-recognized “causal nexus” requirement. Accordingly, the defendant shipbuilder “was entitled to remove this negligence case filed by a former Navy machinist because of his exposure to asbestos while the Navy’s ship was being repaired at the Avondale shipyard under a federal contract.” No. 18-30652 (Feb. 24, 2020). (Above, the formidable bow of the U.S.S. Somerset, the last ship launched from the long-serving shipyard.)

Faced with “extraordinarily confused” case law within the Circuit about the federal-officer removal statute (28 USC sec. 1442(a)(1)), the en banc Court’s opinion in Latiolais v. Huntington Ingalls is intended to “strip away the confusion, align with sister circuits, and rely on the plain language of the statute, as broadened in 2011.” The new test requires a defendant to show: “(1) it has asserted a colorable federal defense, (2) it is a ‘person’ within the meaning of the statute, (3) that has acted pursuant to a federal officer’s directions, and (4) the charged conduct is connected or associated with an act pursuant to a federal officer’s directions.” It abandons a previously-recognized “causal nexus” requirement. Accordingly, the defendant shipbuilder “was entitled to remove this negligence case filed by a former Navy machinist because of his exposure to asbestos while the Navy’s ship was being repaired at the Avondale shipyard under a federal contract.” No. 18-30652 (Feb. 24, 2020). (Above, the formidable bow of the U.S.S. Somerset, the last ship launched from the long-serving shipyard.)

The Fifth Circuit reversed a defense summary judgment in a products case in Certain Underwiters at Lloyd’s v. Axon Pressure Prods., Inc., noting:

Procedurally, a lack of explanation as to key Daubert rulings and related elements of the plaintiff’s claim, characterizing them as “pithy to the point of being incomplete.”

Procedurally, a lack of explanation as to key Daubert rulings and related elements of the plaintiff’s claim, characterizing them as “pithy to the point of being incomplete.”- Substantively, a fact issue on causation, given

conflicting testimony on (a) the handling of the relevant piece of equipment, (b) the reasons for material continuing to flow through that equipment at the time of the accident.

conflicting testimony on (a) the handling of the relevant piece of equipment, (b) the reasons for material continuing to flow through that equipment at the time of the accident.

No. 18-20453 (Feb. 21, 2020).

The Committee for a Qualified Judiciary has published its list of Dallas-area judicial candidates found qualified.

To the right, Elvis sings “Return to Sender.” Similarly, in Rajet Aeroservicios v. Cervantes, the Fifth Circuit reminded: “‘The failure to include a return[-]jurisdiction

To the right, Elvis sings “Return to Sender.” Similarly, in Rajet Aeroservicios v. Cervantes, the Fifth Circuit reminded: “‘The failure to include a return[-]jurisdiction

clause in an [FNC] dismissal constitutes a per se abuse of discretion.” . . . This is because, as our court has repeatedly made clear, ‘courts must take measures, as part of their dismissals in [FNC] cases, to ensure that defendants will not attempt to evade the jurisdiction of the foreign courts.’ Notably, ‘[s]uch measures often include agreements

between the parties to litigate in another forum, to submit to service of process

in that jurisdiction, to waive the assertion of any limitations defenses, to agree

to discovery, and to agree to the enforceability of the foreign judgment.’ A return-jurisdiction clause assists in preventing defendants from circumventing these measures and ensures plaintiffs have the opportunity to proceed with the action in one of the forums.” No. 19-20354 (Feb. 3, 2020) (unpublished) (citations omitted, emphasis added).

Resolution of the tortious-interference claim in Whitney Bank v. SMI Companies Global, Inc. turned on whether the defendant’s profit motive could establish “actual malice” as required by Louisiana law. To the panel majority:

Resolution of the tortious-interference claim in Whitney Bank v. SMI Companies Global, Inc. turned on whether the defendant’s profit motive could establish “actual malice” as required by Louisiana law. To the panel majority:

There is no evidence that Whitney was driven by anything other than profit in its collection efforts. Moreover, the express terms of the contract allowed Whitney to recover from SMI’s customers because both loans were secured by SMI’s accounts receivable. While it may have been more prudent and logical for Whitney to involve SMI in its collection efforts, those efforts, however brusque, served to protect the bank’s legitimate interests—collecting on the defaulted loans.

(citations omitted, emphasis added). The dissent, however:

Often this requirement [of “actual malice”] is insurmountable in the business context because of the “appropriate” motivation of profits. But I disagree with the notion that someone in a corporation who is seeking to collect money from another can never have actual malice or ill will towards that other. Corporations are run by humans, after all. . . . The magistrate judge’s decision rested in part on its determination that Whitney’s employees lacked credibility, and we do not second-guess credibility determinations.

No. 18-31189 (Feb. 3, 2020) (emphais added). (Louisiana’s actual-malice requirement for this tort is uniquely demanding, so this discussion may be less relevant in other jurisdictions.)

In Vizaline, LLC v. Tracy, the Fifth Circuit formally implemented NIFLA v. Becerra, 138 S.Ct. 2361 (2018), in the context of Mississippi’s licensing of surveyors: “The Supreme Court has recently disavowed the notion that occupational licensing regulations are exempt from First Amendment scrutiny. In overturning the “professional speech” doctrine deployed by some circuits, including ours, the Court rejected any theory of the First Amendment that ‘gives the States unfettered power to reduce a group’s First Amendment rights by simply imposing a licensing requirement.’ The district court’s ruling in this case—that Mississippi’s licensing requirements for surveyors do not trigger any First Amendment scrutiny—was inconsistent with NIFLA. We therefore reverse and remand for further proceedings.” No. 19-60053 (Feb. 14, 2020) (citations omitted, emphasis added).

In Vizaline, LLC v. Tracy, the Fifth Circuit formally implemented NIFLA v. Becerra, 138 S.Ct. 2361 (2018), in the context of Mississippi’s licensing of surveyors: “The Supreme Court has recently disavowed the notion that occupational licensing regulations are exempt from First Amendment scrutiny. In overturning the “professional speech” doctrine deployed by some circuits, including ours, the Court rejected any theory of the First Amendment that ‘gives the States unfettered power to reduce a group’s First Amendment rights by simply imposing a licensing requirement.’ The district court’s ruling in this case—that Mississippi’s licensing requirements for surveyors do not trigger any First Amendment scrutiny—was inconsistent with NIFLA. We therefore reverse and remand for further proceedings.” No. 19-60053 (Feb. 14, 2020) (citations omitted, emphasis added).

Gonzales cited two Texas Supreme Court cases, decided after a summary judgment against her, holding that an insurer’s payment of an appraisal award does not preclude a Texas Prompt Payment of Claims Act (“TPPCA”) claim. The Fifth Circuit found that she failed to preserve this argument in the district court. The Court noted that “a change in law . . . does not permit a party to raise an entirely new argument that could have been articulated below”–a rule that applies when a party “could have made the same ‘general argument’ to the district court, but had not done so.” As for the state of the law at the time of the summary-judgment briefing, the Court observed:

Gonzales cited two Texas Supreme Court cases, decided after a summary judgment against her, holding that an insurer’s payment of an appraisal award does not preclude a Texas Prompt Payment of Claims Act (“TPPCA”) claim. The Fifth Circuit found that she failed to preserve this argument in the district court. The Court noted that “a change in law . . . does not permit a party to raise an entirely new argument that could have been articulated below”–a rule that applies when a party “could have made the same ‘general argument’ to the district court, but had not done so.” As for the state of the law at the time of the summary-judgment briefing, the Court observed:

We recognize that several courts, including our own, had previously concluded a TPPCA claim was extinguished as a matter of law after the payment of an appraisal award. But the Supreme Court of Texas granted review in [the two relevant cases] on January 18, 2019, seven days after Allstate moved for summary judgment and thirteen days before Gonzales filed her response to the motion. This fact undermines her assertion here that she “could not have made a good faith argument in the trial court that payment of the appraisal award did not preclude her from recovering under the TPPCA as a matter of law.”

Gonzales v. Allstate Vehicle & Property Ins. Co., No. 19-40250 (Feb. 11, 2020) (emphasis added, footnote omitted).

“[T]he only non-moot challenges to the injunction concern its forward-looking terms, which do not stay any ongoing state-court proceedings. See 28 U.S.C. § 2283

“[T]he only non-moot challenges to the injunction concern its forward-looking terms, which do not stay any ongoing state-court proceedings. See 28 U.S.C. § 2283

(absent specific exceptions, prohibiting federal courts from ‘grant[ing] an injunction to stay proceedings in a State court’); see also Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479, 485 n.2 (1965) (§ 2283 bars only ‘stays of suits already instituted’ but does not ‘preclude injunctions against the institution of state court proceedings’ (citation omitted)).” Hill v. Hunt, No. 18-11633 (revised March 13, 2020).

In re Darden joins the line of cases in which the Fifth Circuit denied a mandamus petition while offering guidance on the issue presented. Darden sought relief from the trial court’s proposed jury charge on a key issue in a wrongful-death case, and the Court held:

In re Darden joins the line of cases in which the Fifth Circuit denied a mandamus petition while offering guidance on the issue presented. Darden sought relief from the trial court’s proposed jury charge on a key issue in a wrongful-death case, and the Court held:

Darden has other adequate means to attain the relief he desires. We are satisfied that on these facts, a writ of mandamus would be inappropriate. Nevertheless, we suggest that the following additional question in the verdict form, one for each officer, upon which the jury’s other findings would not be conditioned, would clearly comply with this court’s prior opinion and possibly avoid another appeal regarding these instructions after a verdict.

QUESTION NO. [#]

Do you find from a preponderance of the evidence that [officer’s name] knew or should have known of the existence and extent of Jermaine Darden’s preexisting conditions?

No. 20-10065 (Feb. 7, 2020).

A not-unusual series of events involving a settlement agreement led to a practice tip in Defense Distributed v. U.S. Dep’t of State, No.18-05911 (Jan. 21, 2020):

A not-unusual series of events involving a settlement agreement led to a practice tip in Defense Distributed v. U.S. Dep’t of State, No.18-05911 (Jan. 21, 2020):

- Plaintiffs sued several government entities about their right to publish online plans for the “Liberator” (right) a firearm that could be made with a 3-D printer;

- That lawsuit settled, favorably for the publisher;

- The settling parties filed a Rule 41(a)(1)(A)(ii) stipulation of dismissal;

- A few days later, the district court (purported to) enter a final judgment;

- Various states brought a new lawsuit in another federal court to enjoin the settlement; leading the original plaintiffs to try and reopen the case under Fed. R. Civ. P. 59(e).

The Fifth Circuit found that the stipulation divested the district court of jurisdiction, dooming the request to reopen. The Court suggested: “If the parties had wanted to, they could have asked the district court to retain jurisdiction–for example, to oversee enforcement of a settlement agreement.” (citations omitted).

The Texas Supreme Court’s recent opinion in JP Morgan Chase v. Orca Assets, 546 S.W.3d 648 (Tex. 2018) has significantly influenced commercial litigation, particularly with its focus on “red flags” about a questionable transaction. In Universal Truckload, Inc. v. Dalton Logistics, Inc., Ni. 17-20725 (Jan. 3, 2020), a promissory estoppel case, the Fifth Circuit observed: “[T[his case differs from JPMorgan in at least three crucial ways. First, the letter of intent at issue in JPMorgan was a binding contract signed by both parties. The [Indication of Interest (“IOI”] that Universal Truckload sent Dalton is expressly nonbinding. Second, the letter of intent in JPMorgan included a clause disclaiming any oral agreements. Universal Truckload’s IOI does not. And third, the letter of intent in JPMorgan directly contradicted the oral promise, and Universal Truckload’s IOI does not. The Supreme Court of Texas explained in JPMorgan, ‘there is no direct contradiction if a reasonable person can read the writing and still plausibly claim to believe the [oral] representation.’ The conditions laid out in the IOI explain what would need to happen if Universal Truckload was to enter a contract to purchase Dalton. But the jury did not find in favor of Dalton on a contract theory. Dalton succeeded on a promissory estoppel theory, which requires the absence of a contract.”

The Texas Supreme Court’s recent opinion in JP Morgan Chase v. Orca Assets, 546 S.W.3d 648 (Tex. 2018) has significantly influenced commercial litigation, particularly with its focus on “red flags” about a questionable transaction. In Universal Truckload, Inc. v. Dalton Logistics, Inc., Ni. 17-20725 (Jan. 3, 2020), a promissory estoppel case, the Fifth Circuit observed: “[T[his case differs from JPMorgan in at least three crucial ways. First, the letter of intent at issue in JPMorgan was a binding contract signed by both parties. The [Indication of Interest (“IOI”] that Universal Truckload sent Dalton is expressly nonbinding. Second, the letter of intent in JPMorgan included a clause disclaiming any oral agreements. Universal Truckload’s IOI does not. And third, the letter of intent in JPMorgan directly contradicted the oral promise, and Universal Truckload’s IOI does not. The Supreme Court of Texas explained in JPMorgan, ‘there is no direct contradiction if a reasonable person can read the writing and still plausibly claim to believe the [oral] representation.’ The conditions laid out in the IOI explain what would need to happen if Universal Truckload was to enter a contract to purchase Dalton. But the jury did not find in favor of Dalton on a contract theory. Dalton succeeded on a promissory estoppel theory, which requires the absence of a contract.”

A fatal injury at the L’Auberge Casino in Lake Charles, Louisiana, led to litigation in Texas against the casino’s owner. The plaintiffs asserted general personal jurisdiction based on the casino’s substantial marketing efforts directed toward Texas. The Fifth Circuit acknowledged “a handful of . . . district court cases finding general jurisdiction against non-resident casinos for their localized marketing efforts,” but found that recent Supreme Court opinions about general jurisdiction meant that “local advertising, as a standalone factor, does not meet ‘the demanding nature of the standard for general personal jurisdiction over a corporation.'” Frank v. P N K (Lake Charles) LLC, No. 18-31060 (Jan. 21, 2020) (applying, inter alia, Daimler AG v. Bauman, 571 U.S. 117 (2014)).

A fatal injury at the L’Auberge Casino in Lake Charles, Louisiana, led to litigation in Texas against the casino’s owner. The plaintiffs asserted general personal jurisdiction based on the casino’s substantial marketing efforts directed toward Texas. The Fifth Circuit acknowledged “a handful of . . . district court cases finding general jurisdiction against non-resident casinos for their localized marketing efforts,” but found that recent Supreme Court opinions about general jurisdiction meant that “local advertising, as a standalone factor, does not meet ‘the demanding nature of the standard for general personal jurisdiction over a corporation.'” Frank v. P N K (Lake Charles) LLC, No. 18-31060 (Jan. 21, 2020) (applying, inter alia, Daimler AG v. Bauman, 571 U.S. 117 (2014)).

I spoke at the State Bar’s “Litigation Update” last Friday to give a Supreme Court and Fifth Circuit update; here is my PowerPoint from that presentation. It covers SCOTUS and CTA5 cases of general interest to business litigators since the last Litigation Update seminar in January 2019.

I spoke at the State Bar’s “Litigation Update” last Friday to give a Supreme Court and Fifth Circuit update; here is my PowerPoint from that presentation. It covers SCOTUS and CTA5 cases of general interest to business litigators since the last Litigation Update seminar in January 2019.

The General Land Office of Texas disputed the Interior Department’s decision to continue protection of the golden-cheeked warbler as an endangered species. The Fifth Circuit found the Department’s process flawed: “The Service recited this standard, but a careful examination of its analysis shows that the Service applied an inappropriately heightened one.Specifically, to proceed to the twelve-month review stage, the Service required the delisting petition to contain information that the Service had not considered in its five-year review that was sufficient to refute that review’s conclusions. . . .The Service thus based its decision to deny the delisting petition on an incorrect legal standard. Consequently, we conclude that the Service’s decision was arbitrary and capricious. We therefore vacate that decision and remand for the Service to evaluate the delisting petition under the correct legal standard.” General Land Office of Texas v. U.S. Dep’t of the Interior, No. 19-50178 (Jan. 15, 2020) (emphasis in original).

standard, but a careful examination of its analysis shows that the Service applied an inappropriately heightened one.Specifically, to proceed to the twelve-month review stage, the Service required the delisting petition to contain information that the Service had not considered in its five-year review that was sufficient to refute that review’s conclusions. . . .The Service thus based its decision to deny the delisting petition on an incorrect legal standard. Consequently, we conclude that the Service’s decision was arbitrary and capricious. We therefore vacate that decision and remand for the Service to evaluate the delisting petition under the correct legal standard.” General Land Office of Texas v. U.S. Dep’t of the Interior, No. 19-50178 (Jan. 15, 2020) (emphasis in original).

“[S]tatutory damages do not only approximate a copyright owner’s consequential damages. Statutory damages also serve an independent deterrent purpose; therefore, mitigation rules do not wholly preclude recovery of statutory damages.” Energy Intelligence Group, Inc. v. Kayne Anderson Capital Advisors, LP, No. 18-20350 (Jan .15, 2020). This case also provides a case study in the multiplication of copyright damages resulting from the unauthorized recirculation of a copyrighted publication.

“[S]tatutory damages do not only approximate a copyright owner’s consequential damages. Statutory damages also serve an independent deterrent purpose; therefore, mitigation rules do not wholly preclude recovery of statutory damages.” Energy Intelligence Group, Inc. v. Kayne Anderson Capital Advisors, LP, No. 18-20350 (Jan .15, 2020). This case also provides a case study in the multiplication of copyright damages resulting from the unauthorized recirculation of a copyrighted publication.

The arbitration clause in Kemper Corporate Servcs., Inc. v. Computer Sciences Corp., No. 18-11276 (Jan. 10, 2020), said that “decisions shall be in writing and shall state the findings of fact and conclusions of law upon which the decision is based, provided that such decision may not (i) award consequential, punitive, special, incidental or exemplary damages or any amounts in excess of the limitations delineated in” other provisions of the parties’ contracts (emphasis added). The unsuccessful party questioned whether the arbitrator had authority to “categorize damages as consequential or direct,” but the Fifth Circuit disagreed, concluding: “For the arbitrator to resolve the dispute between CSC and Kemper, which could include awarding damages, he had to categorize the potential damages into the permitted and the prohibited categories.” The Court then affirmed under the highly-deferential standard of review as stated in BNSF R.R. Co. v. Alstom Transp., 777 F.3d 785 (5th Cir. 2015).

The arbitration clause in Kemper Corporate Servcs., Inc. v. Computer Sciences Corp., No. 18-11276 (Jan. 10, 2020), said that “decisions shall be in writing and shall state the findings of fact and conclusions of law upon which the decision is based, provided that such decision may not (i) award consequential, punitive, special, incidental or exemplary damages or any amounts in excess of the limitations delineated in” other provisions of the parties’ contracts (emphasis added). The unsuccessful party questioned whether the arbitrator had authority to “categorize damages as consequential or direct,” but the Fifth Circuit disagreed, concluding: “For the arbitrator to resolve the dispute between CSC and Kemper, which could include awarding damages, he had to categorize the potential damages into the permitted and the prohibited categories.” The Court then affirmed under the highly-deferential standard of review as stated in BNSF R.R. Co. v. Alstom Transp., 777 F.3d 785 (5th Cir. 2015).

Among other challenges to a $65 million arbitration award, Catic USA disputed the claimants’ damages calculation. The Fifth Circuit rejected the challenge, in part because the shortcomings were of Catic’s own making: “Catic USA does not contest that AVIC’s anticipated rate of return was 15% or that the panel employed an appropriate discount rate; instead, it attacks the panel’s assumption that AVIC’s investment did (or would) generate profits. It is true that, although the amount of lost profits may be estimated, claimants generally ‘must show that there would [have been] some future profits’ but for the breach. But in this case, Catic USA has refused to provide the relevant information, and it was thus within the arbitration panel’s authority to infer that AVIC’s investment was indeed profitable.” Soaring Wind Energy LLC v. Catic USA Inc., No. 18-11192 (Jan. 7, 2020) (citation omitted, emphasis added). .