A notable feature of the Fifth Circuit’s new typography is the amount of kerning (spacing between of letters) in certain elements of an opinion’s first page. (And for those who are

A notable feature of the Fifth Circuit’s new typography is the amount of kerning (spacing between of letters) in certain elements of an opinion’s first page. (And for those who are  weary of the “cases in footnotes,” “1-space, 2-space,” or “anything but Times New Roman” topics, kerning offers an entirely new topic of discussion.) What are your thoughts on appellate kerning?

weary of the “cases in footnotes,” “1-space, 2-space,” or “anything but Times New Roman” topics, kerning offers an entirely new topic of discussion.) What are your thoughts on appellate kerning?

“Applying Skidmore, we ask whether EPA’s interpretation of Title V in the Hunter Order is persuasive. Specifically, we inquire into the persuasiveness of EPA’s current view that the Title V permitting process does not require substantive reevaluation of the underlying Title I preconstruction permits applicable to a pollution source. As we read it, the Hunter Order defends the agency’s interpretation based principally on Title V’s text, Title V’s structure and purpose, and the structure of the Act as a whole. Having examined these reasons and found them persuasive, we conclude that EPA’s current approach to Title V merits Skidmore deference.” Environmental Integrity Project v. EPA, No. 18-60384 (Aug. 13, 2020) (emphasis added).

“Applying Skidmore, we ask whether EPA’s interpretation of Title V in the Hunter Order is persuasive. Specifically, we inquire into the persuasiveness of EPA’s current view that the Title V permitting process does not require substantive reevaluation of the underlying Title I preconstruction permits applicable to a pollution source. As we read it, the Hunter Order defends the agency’s interpretation based principally on Title V’s text, Title V’s structure and purpose, and the structure of the Act as a whole. Having examined these reasons and found them persuasive, we conclude that EPA’s current approach to Title V merits Skidmore deference.” Environmental Integrity Project v. EPA, No. 18-60384 (Aug. 13, 2020) (emphasis added).

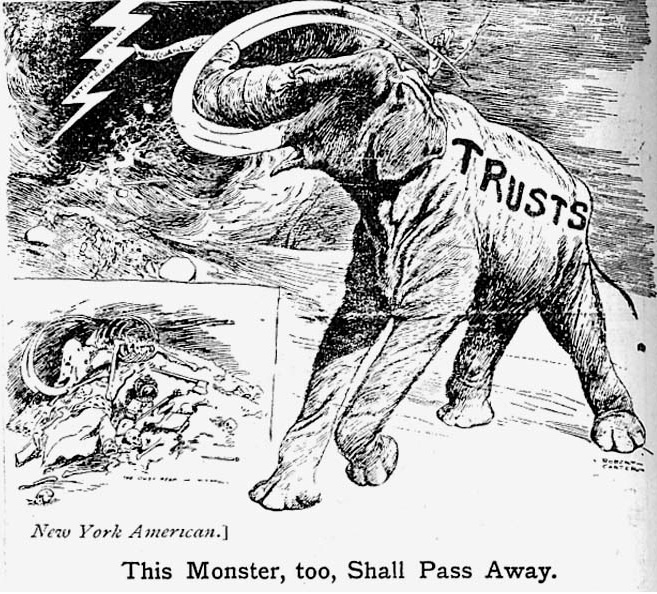

My newest Coale Mind podcast episode looks forward to this fall, when the Supreme Court will consider two decisions by the en banc (full) U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, the federal appellate court for Texas.

My newest Coale Mind podcast episode looks forward to this fall, when the Supreme Court will consider two decisions by the en banc (full) U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, the federal appellate court for Texas.

In the first, California v. Texas, a Fifth Circuit panel found that the individual mandate of the Affordable Care Act was unconstitutional after the repeal of the relevant tax, and the en banc court denied review in a close vote. In the second, Collins v. Mnuchin, the en banc Fifth Circuit found that Fannie Mae’s regulator was structured unconstitutionally.

These cases, important in their own right, also reflect a fascinating encounter between two “conservative” federal courts. Will the Fifth Circuit, widely seen as a particularly conservative court after President Trump’s many appointments, be seen by the Roberts Court as having gone too far? Or will the two courts by “in synch” with each other on these important constitutional issues?

In Six Dimensions, Inc. v. Perficient, Inc., the Fifth Circuit concluded that under California noncompete law, the parties’ “2014 Agreement” was unenforceable. A key question was whether their “2015 Agreement” was also subject to that conclusion, or whether it was separate and the arguments against it had been waived in the trial court. The Court found no waiver, concluding that the below language was insufficient notice that the plaintiff was seeking summary judgment about that contract.

In Six Dimensions, Inc. v. Perficient, Inc., the Fifth Circuit concluded that under California noncompete law, the parties’ “2014 Agreement” was unenforceable. A key question was whether their “2015 Agreement” was also subject to that conclusion, or whether it was separate and the arguments against it had been waived in the trial court. The Court found no waiver, concluding that the below language was insufficient notice that the plaintiff was seeking summary judgment about that contract.

“Defendant argues that Brading was permitted to engage in this wrongful conduct because the contract that she signed, contained a provision that is not allowed under California law. Defendant argues that even though the Amended Complaint does not accuse Brading of breaching the non-competition portion of the 2014 Agreement [Dkt 10-2], that its presence in the 2014 Agreement invalidates that agreement. Texas has no such provision. It is respectfully submitted, as asserted in the Complaint, that the law of Texas applies and as such, the 2014 Agreement is clearly breached by Brading’s undisputed conduct in violating both portions of the 2014 Agreement. Further, there is no noncompetition portion for the Termination Certification signed by Brading in June of 2015 and as such, under the law of either State, Brading is responsible for violating the 2015 Agreement.”

No. 19-20505 (Aug. 7, 2020) (emphasis added).

The Fifth Circuit found it was an abuse of discretion to not reform a noncompetition agreement at the preliminary-injunction stage, rejecting the argument that reformation “is a remedy to be granted at a final hearing, whether on the merits or by summary judgment, not as interim relief.” The Court held: “This argument runs against the clear majority practice of Texas courts, which have on many occasions reformed contracts for the purposes of granting interim relief. The Texas case that has most thoroughly considered the question has rejected the argument Calhoun makes here, finding that reformation ‘is not only a final remedy’ and may be made ‘as an incident to the granting of injunctive relief.'” Calhoun v. Jack Doheney Cos., No. 20-20068 (Aug. 7, 2020).

“The Texas Supreme Court has held that a Texas court of civil appeals does not have jurisdiction to initiate an award of appellate attorneys’ fees because ‘the award of any attorney fee is a fact issue which must [first] be passed upon the trial court.’” In Texas state courts, requesting appellate fees at the original trial is a placeholder requirement to ensure the state trial courts maintain jurisdiction over the issue. Those are procedural rules that do not apply in federal court. Our local rules provide for appellate litigants to petition this court for. Local Rule 47.8 does not require a party seeking appellate attorneys’ fees to first request appellate attorneys’ fees in the district court as a placeholder.” Atom Instrument Corp. v. Petroleum Analyzer Co., No. 19-20151 (Aug. 7, 2020) (citations omitted).

“The Texas Supreme Court has held that a Texas court of civil appeals does not have jurisdiction to initiate an award of appellate attorneys’ fees because ‘the award of any attorney fee is a fact issue which must [first] be passed upon the trial court.’” In Texas state courts, requesting appellate fees at the original trial is a placeholder requirement to ensure the state trial courts maintain jurisdiction over the issue. Those are procedural rules that do not apply in federal court. Our local rules provide for appellate litigants to petition this court for. Local Rule 47.8 does not require a party seeking appellate attorneys’ fees to first request appellate attorneys’ fees in the district court as a placeholder.” Atom Instrument Corp. v. Petroleum Analyzer Co., No. 19-20151 (Aug. 7, 2020) (citations omitted).

The ABA House of Delegates has recently adopted a comprehensive set of best practices for litigation funding–an important topic in modern law practice.

The ABA House of Delegates has recently adopted a comprehensive set of best practices for litigation funding–an important topic in modern law practice.

OSHA regulations have an exemption for “diving performed solely as a necessary part of a scientific, research, or educational activity by employees whose sole purpose for diving is to perform scientific research tasks. Scientific diving does not include performing any tasks usually associated with commercial diving such as: Placing or removing heavy objects underwater; inspection of pipelines and similar objects; construction; demolition; cutting or welding; or the use of explosives.”

OSHA regulations have an exemption for “diving performed solely as a necessary part of a scientific, research, or educational activity by employees whose sole purpose for diving is to perform scientific research tasks. Scientific diving does not include performing any tasks usually associated with commercial diving such as: Placing or removing heavy objects underwater; inspection of pipelines and similar objects; construction; demolition; cutting or welding; or the use of explosives.”

OSHA concluded that the divers who clean the tanks at the Houston Aquarium were not “scientific divers” under this regulation; the Fifth Circuit saw otherwise: “The divers are engaged in a ‘studious … examination’ and ‘detailed study’ when they observe the animals for abnormalities, and when they work to keep the animals in the Aquarium alive, healthy, and breeding. That an organization collaborates among employees and engages in verbal communication does not mean that the examination and study of the animals in the tanks is not ‘studious’ or ‘detailed.’ Nothing about the feeding and cleaning dives renders the information that the trained scientists performing the dives gather during these dives outside of the definition of ‘research.’” Houston Aquarium, Inc. v. OSHRC, No. 19-60245 (July 15, 2020).

Many forum-selection disputes, particularly about arbitration clauses, turn on whether the parties’ contract incorporates another document. A variation on this common fact pattern appeared in Sierra Frac Sand v. CDE Global, No. 19-40489 (May 26, 2020),”Sierra concedes that some document was incorporated into the contract. Indeed, by making the agreement ‘subject to’ the ‘Standard Terms and Conditions of Sale” that were available on request, the contract explicitly refers to another document. The question for us is whether the document titled ‘CDE General Conditions – June 2016’ is the incorporated document.”

Many forum-selection disputes, particularly about arbitration clauses, turn on whether the parties’ contract incorporates another document. A variation on this common fact pattern appeared in Sierra Frac Sand v. CDE Global, No. 19-40489 (May 26, 2020),”Sierra concedes that some document was incorporated into the contract. Indeed, by making the agreement ‘subject to’ the ‘Standard Terms and Conditions of Sale” that were available on request, the contract explicitly refers to another document. The question for us is whether the document titled ‘CDE General Conditions – June 2016’ is the incorporated document.”

The answer was “yes,” given evidence that:

- “before this lawsuit commenced …, CDE sent Sierra the 2016 addendum as an attachment to a letter about the project’s timeline,” and “CDE’s financial director attested that the 2016 addendum was the document referred to in the order acknowledgement”;

- “CDE explained that the addendum was dated 2016, even though the contract was executed in 2017, because when the agreement was signed, the 2016 addendum was the most current version of CDE’s terms and conditions”; and,

- “… as the district court found, the 2016 addendum contained the kind of terms and conditions one would expect to accompany the parties’ agreement.”

No. 19-40489 (May 26, 2020).

Ecclesiastes 3:1-8 instructs: “For everything there is a season, and a time for every [a]purpose under heaven: a time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted,” and so forth. McRaney v. North American Board of the Southern Baptist Convention instructs: “At this early stage of the litigation, it is not clear that any of these [necessary] determinations will require the court to address purely ecclesiastical

Ecclesiastes 3:1-8 instructs: “For everything there is a season, and a time for every [a]purpose under heaven: a time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted,” and so forth. McRaney v. North American Board of the Southern Baptist Convention instructs: “At this early stage of the litigation, it is not clear that any of these [necessary] determinations will require the court to address purely ecclesiastical

questions. McRaney is not challenging the termination of his employment, and he is not asking the court to

weigh in on issues of faith or doctrine[.] His complaint asks the court to apply neutral principles of tort law

to a case that, on the face of the complaint, involves a civil rather than religious dispute.” (citations omitted).

Acknowledging the Supreme Court’s recent reminder that “[t]he First Amendment protects the right of religious institutions ‘to decide for themselves, free from state interference, matters of church government as well as those of faith and doctrine,” the Court held: “At this time, it is not certain that resolution of McRaney’s claims will require the court to interfere with matters of church government, matters of faith, or matters of doctrine. The district court’s dismissal was premature.” No. 19-60293 (July 16, 2020).

The parties’ arbitration agreement adopted certain AAA rules; among them, Rule 52(e) says: “Parties to an arbitration under these rules may not call the arbitrator . . . as a witness in litigation or any other proceeding relating to the arbitration” and that an arbitrator is “not competent to testify as [a] witness[] in such proceeding.”

The parties’ arbitration agreement adopted certain AAA rules; among them, Rule 52(e) says: “Parties to an arbitration under these rules may not call the arbitrator . . . as a witness in litigation or any other proceeding relating to the arbitration” and that an arbitrator is “not competent to testify as [a] witness[] in such proceeding.”

The appellant in Vantage Deepwater Co. v. Petrobras, facing an award of close to $700 million, sought the deposition of the dissenter on a 3-judge panel, noting his unusual statement that “the entire arbitration, ‘the prehearing, hearing, and posthearing processes,’ denied Petrobras ‘fundamental fairness and due process protections.'”

The Fifth Circuit held otherwise: “We have not discovered any court of appeals decision holding that a district court abused its discretion in denying discovery from an arbitrator about the substance of the award. We see nothing in this record to cause us to be the first.” No. 19-20435 (July 16, 2020).

“Jackson [National Life]’s objection to personal jurisdiction concerned only class members who were non-residents of Texas. Those members, however, were not yet before the court when Jackson filed its Rule 12 motions. What brings putative class members before the court is certification: ‘Certification of a class is the critical act which reifies the unnamed class members and, critically, renders them subject to the court’s power.’ When Jackson filed its pre-certification Rule 12 motions, however, the only live claims belonged to the named plaintiffs, all Texas residents as to whom Jackson conceded personal jurisdiction.” Accordingly, Jackson did not waive the issue of personal jurisdiction by raising it in the proceedings about certification. Cruson v. Jackson National Life, No. 18-40605 (March 25, 2020).

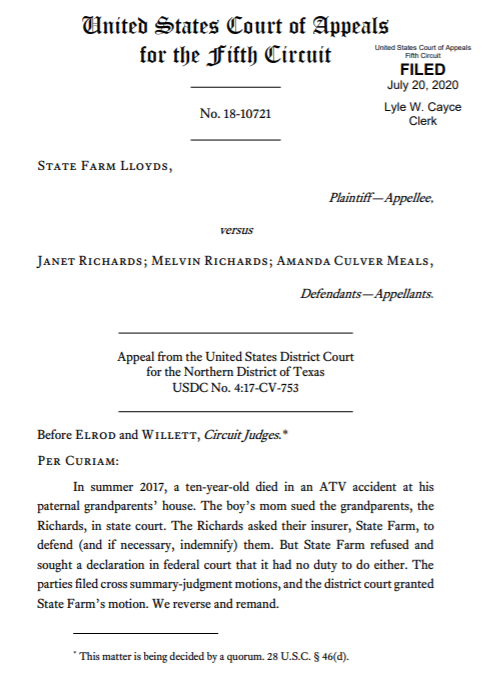

For insurance-coverage lawyers, State Farm Lloyds v. Richards represents another case in which the Fifth Circuit concludes that “the eight-corners rule applies here; the ‘very narrow exception’ does not,” and then finds that the relevant pleading “contains

For insurance-coverage lawyers, State Farm Lloyds v. Richards represents another case in which the Fifth Circuit concludes that “the eight-corners rule applies here; the ‘very narrow exception’ does not,” and then finds that the relevant pleading “contains

allegations within its four corners that potentially constitute a claim within the four corners of the policy.” No. 18-10721 (July 19, 2020).

For fans of legal typography, State Farm Lloyds represents a daring new look – stylish, yet readable!

For fans of legal typography, State Farm Lloyds represents a daring new look – stylish, yet readable!

Please check out my new podcast, Coale Mind, where once a week I talk about constitutional and other legal issues of the day. This forum lets me get into more detail than other media appearances, while also approaching issue from a less technical perspective than blogging and other professional writing. I hope you enjoy it and choose to subscribe! Available on Spotify, Apple, and other such services.

Please check out my new podcast, Coale Mind, where once a week I talk about constitutional and other legal issues of the day. This forum lets me get into more detail than other media appearances, while also approaching issue from a less technical perspective than blogging and other professional writing. I hope you enjoy it and choose to subscribe! Available on Spotify, Apple, and other such services.

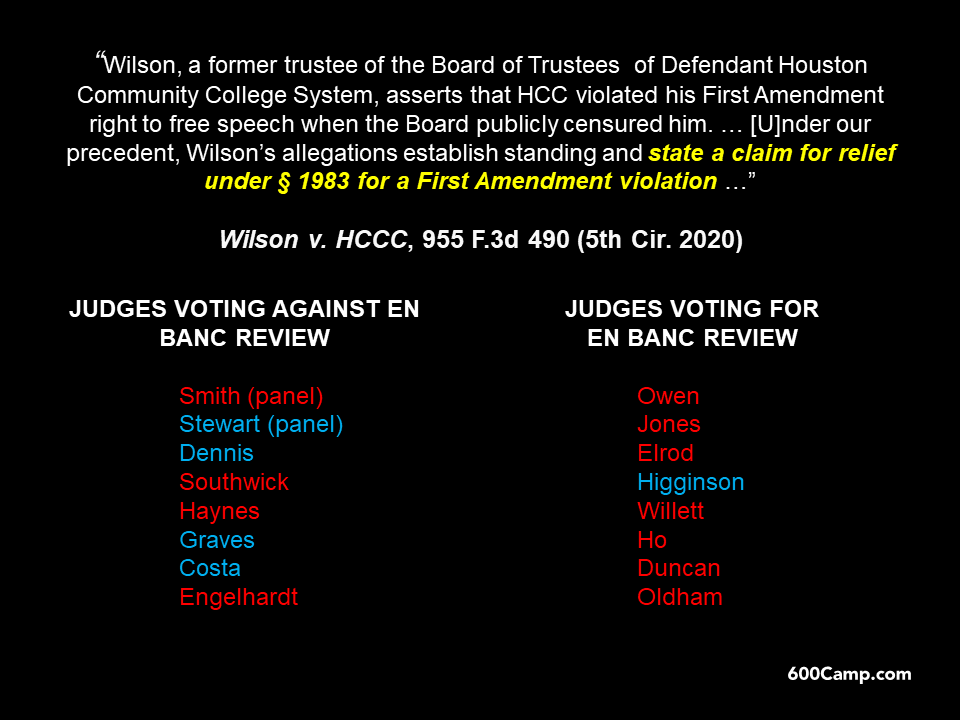

Wilson, a trustee of Houston’s community-college system, alleged that his censure by the board was done in retaliation for his exercise of First Amendment rights. A panel found that he had stated a claim that was sufficient to survive a Rule 12 challenge:

Wilson, a trustee of Houston’s community-college system, alleged that his censure by the board was done in retaliation for his exercise of First Amendment rights. A panel found that he had stated a claim that was sufficient to survive a Rule 12 challenge:

The above [Circuit] precedent establishes that a reprimand against an elected official for speech addressing a matter of public concern is an actionable First Amendment claim under § 1983. Here, the Board’s censure of Wilson specifically noted it was punishing him for “criticizing other Board members for taking positions that differ from his own” concerning the Qatar campus, including robocalls, local press interviews, and a website. The censure also punished Wilson for filing suit alleging the Board was violating its bylaws. As we have previously held, “[R]eporting municipal corruption undoubtedly constitutes speech on a matter of public concern.” Therefore, we hold that Wilson has stated a claim against HCC under § 1983 in alleging that its Board violated his First Amendment right to free speech when it publicly censured him.

Wilson v. Houston Community College System, 955 F.3d 490 (5th Cir. 2020) (footnote omitted). A vote to take the case en banc produced an 8-8 tie, with these votes (Senior Judge Eugene Davis, who wrote the panel opinion, was not part of the en banc vote):

An alleged tortfeasor, earlier named as a party in a case, settled with the plaintiff. The plaintiff sought to submit a conspiracy count related to that party, and the Fifth Circuit agreed: “The alleged co-conspirator need not actually face liability. … [A]settlement in general does not prevent submitting to the jury questions about that party’s conduct (only pursuing an actual judgment against the settling party). Therefore, we conclude that Phadia’s settlement had no bearing on the Plaintiffs’ ability to prove a civil conspiracy case against the Defendants based on an underlying tort committed by Phadia.” United Biologics v. Allergy & Asthma Network, No. 19-50257 (June 24, 2020) (unpublished).

An alleged tortfeasor, earlier named as a party in a case, settled with the plaintiff. The plaintiff sought to submit a conspiracy count related to that party, and the Fifth Circuit agreed: “The alleged co-conspirator need not actually face liability. … [A]settlement in general does not prevent submitting to the jury questions about that party’s conduct (only pursuing an actual judgment against the settling party). Therefore, we conclude that Phadia’s settlement had no bearing on the Plaintiffs’ ability to prove a civil conspiracy case against the Defendants based on an underlying tort committed by Phadia.” United Biologics v. Allergy & Asthma Network, No. 19-50257 (June 24, 2020) (unpublished).

The parties in Acadian Diagnostic Laboratories v. Quality Toxicology, LLC disputed what the phrase “customary billing practices” meant in their contract. QT argued that it meant “the billing practices that [Acadian] habitually or usually used with its customers in general,” while Acadian “asserts that it agreed to use the billing practices that it habitually or usually used with QT.” The Fifth Circuit resolved this dispute by reference to the parties’ performance, finding that “the record is entirely one-sided,” and that Acadian’s interpretation was consistent with the parties’ performance both before and after the formatoin of their contract. No. 19-30320 (July 13, 2020).

Soren Kierkegaard wondered, “What is the Absurd?” Contemporary artist Michael Cheval creates thought-provoking works of absurdist art (to the right, “Echo of Misconception” (2015)). And the Fifth Circuit plumbed the meaning of the absurd in Geovera Specialty Ins. Co. v. Joachin, No. 19-30604 (July 6, 2020), in a coverage dispute about a homeowners’ insurance policy, bserving: “Absurdity requires a result ‘that no reasonable person could approve.’ An insurance policy is thus absurd if it ‘exclude[s] all coverage’ from the outset. So is one that broadly excludes coverage without reasonable limitations. But the GeoVera policy is not absurd on its face. The policy makes perfect sense for a homeowner who purchases it while already living in the home.” No. 19-30605 (July 6, 2020) (citations omitted).

Soren Kierkegaard wondered, “What is the Absurd?” Contemporary artist Michael Cheval creates thought-provoking works of absurdist art (to the right, “Echo of Misconception” (2015)). And the Fifth Circuit plumbed the meaning of the absurd in Geovera Specialty Ins. Co. v. Joachin, No. 19-30604 (July 6, 2020), in a coverage dispute about a homeowners’ insurance policy, bserving: “Absurdity requires a result ‘that no reasonable person could approve.’ An insurance policy is thus absurd if it ‘exclude[s] all coverage’ from the outset. So is one that broadly excludes coverage without reasonable limitations. But the GeoVera policy is not absurd on its face. The policy makes perfect sense for a homeowner who purchases it while already living in the home.” No. 19-30605 (July 6, 2020) (citations omitted).

In Williams v. MMO Behavioral Health Systems, the Fifth Circuit affirmed a $244,000 judgment for defamation, entered after a jury trial. Good record keeping often benefits defendants in employment-related litigation, but in this case it helped the plaintiff on a key issue:

In Williams v. MMO Behavioral Health Systems, the Fifth Circuit affirmed a $244,000 judgment for defamation, entered after a jury trial. Good record keeping often benefits defendants in employment-related litigation, but in this case it helped the plaintiff on a key issue:

Before MMO had published the statement to the [Louisiana Workforce Commission], Williams had informed MMO that she did not falsify her timecard. This should have led MMO to examine Williams’s timecard. If MMO had done so, it would have discovered that even though Williams regularly clocked in every day, the timecard facially showed that someone else clocked in Williams on July 5th. This fact indicates that MMO should have known that Williams was not the one falsifying her timecard. The times for which Williams was clocked in on July 5th were also not her normal working hours, further suggesting that Williams was not the one to clock in on July 5th. Moreover, Williams did not fill out a missed-clock-punch form, which would have been necessary to allow someone else to clock her in or out, suggesting that Williams was not even involved with this July 5th clocking in and out.

No. 19-30757 (July 9, 2020) (unpublished).

The trap: “The Funds sought to render an interlocutory decision appealable by dismissing at least one defendant without prejudice. And under [Williams v. Seidenbach, 958 F.3d 341, 369 (5th Cir. 2020) (en banc)], that means—absent some further act like a Rule 54(b) certification—there is no final, appealable decision.”

The trap: “The Funds sought to render an interlocutory decision appealable by dismissing at least one defendant without prejudice. And under [Williams v. Seidenbach, 958 F.3d 341, 369 (5th Cir. 2020) (en banc)], that means—absent some further act like a Rule 54(b) certification—there is no final, appealable decision.”

The hint: “Because the dismissal without prejudice in this case occurred after the order the Funds seek to appeal, we do not decide how Williams . . . would apply where the dismissal occurred before the adverse, interlocutory order. See Schoenfeld v. Babbitt 168 F.3d 1257, 1265–66 (11th Cir. 1999) (concluding that there was a final decision in such a case).”

The hint: “Because the dismissal without prejudice in this case occurred after the order the Funds seek to appeal, we do not decide how Williams . . . would apply where the dismissal occurred before the adverse, interlocutory order. See Schoenfeld v. Babbitt 168 F.3d 1257, 1265–66 (11th Cir. 1999) (concluding that there was a final decision in such a case).”

Firefighters’ Retirement System v. Citco Group Ltd., No. 19-30165 (July 7, 2020).

After the plaintiff voluntarily dismissed the federal securities claims that justified removal, the district court retained jurisdiction over the case based on supplemental jurisdiction and granted a motion to compel arbitration. The Fifth Circuit rejected the supplemental-jurisdiction argument and vacated the motion to compel: “All of SJAP’s claims against Cigna arise from or concern the In-Network Agreement and the resulting business relationship. SJAP’s federal claim against the Insight Defendants, by contrast, was based on SJAP’s purchase of securities from Insight as part of the Lab Operating Agreement, a completely separate contract that had nothing to do with Cigna that was consummated several years before the events giving rise to SJAP’s claims against Cigna. Other than SJAP’s vague assertion that Insight and the Cigna Affiliates previously ‘had a lengthy and sordid relationship’ that resulted in an undisclosed settlement agreement, the operative complaint when the case was removed demonstrated no connection between Cigna and the Insight controversy, let alone the specific federal security claim that conferred original jurisdiction on the district court.” SJ Associated Pathologists v. Cigna Healthcare of Texas, No. 20-20188 (July 6, 2020) (emphasis added).

After the plaintiff voluntarily dismissed the federal securities claims that justified removal, the district court retained jurisdiction over the case based on supplemental jurisdiction and granted a motion to compel arbitration. The Fifth Circuit rejected the supplemental-jurisdiction argument and vacated the motion to compel: “All of SJAP’s claims against Cigna arise from or concern the In-Network Agreement and the resulting business relationship. SJAP’s federal claim against the Insight Defendants, by contrast, was based on SJAP’s purchase of securities from Insight as part of the Lab Operating Agreement, a completely separate contract that had nothing to do with Cigna that was consummated several years before the events giving rise to SJAP’s claims against Cigna. Other than SJAP’s vague assertion that Insight and the Cigna Affiliates previously ‘had a lengthy and sordid relationship’ that resulted in an undisclosed settlement agreement, the operative complaint when the case was removed demonstrated no connection between Cigna and the Insight controversy, let alone the specific federal security claim that conferred original jurisdiction on the district court.” SJ Associated Pathologists v. Cigna Healthcare of Texas, No. 20-20188 (July 6, 2020) (emphasis added).

Digidrill sued for unjust enrichment, “alleging [that] Petrolink hacked into its software at various oil drilling sites in order to ‘scrape’ valuable drilling data in real time.” The Fifth Circuit held: “Digirill’s claim is not preempted by copyright because—like the claim in GlobeRanger—it requires establishing that Petrolink engaged in wrongful conduct beyond mere reproduction: namely, the taking of an undue advantage. Under Texas law an unjust enrichment claim requires showing that one party ‘has obtained a benefit from another by fraud, duress, or the taking of an undue advantage.’ Digidrill … contends Petrolink obtained a benefit by taking undue advantage when it surreptitiously installed [certain software]. This is the claim Digidrill put to the jury. Like the alleged misappropriation-of-trade-secrets claim in GlobeRanger, which required establishing improper means or breach of a confidential relationship, Digidrill’s alleged unjust enrichment claim requires establishing wrongful conduct—i.e., inducing the MWD

Digidrill sued for unjust enrichment, “alleging [that] Petrolink hacked into its software at various oil drilling sites in order to ‘scrape’ valuable drilling data in real time.” The Fifth Circuit held: “Digirill’s claim is not preempted by copyright because—like the claim in GlobeRanger—it requires establishing that Petrolink engaged in wrongful conduct beyond mere reproduction: namely, the taking of an undue advantage. Under Texas law an unjust enrichment claim requires showing that one party ‘has obtained a benefit from another by fraud, duress, or the taking of an undue advantage.’ Digidrill … contends Petrolink obtained a benefit by taking undue advantage when it surreptitiously installed [certain software]. This is the claim Digidrill put to the jury. Like the alleged misappropriation-of-trade-secrets claim in GlobeRanger, which required establishing improper means or breach of a confidential relationship, Digidrill’s alleged unjust enrichment claim requires establishing wrongful conduct—i.e., inducing the MWD

companies to violate the express terms of their DataLogger licenses—that goes

beyond mere copying.” Digital Drilling Data Sysems LLC v. Petrolink Servcs., Inc., No. 19-20116 (July 2, 2020) (footnote omitted, emphasis added). The Court noted that a different type of unjust-enrichment claim could potentially lead to a different result.

When not engaged in good-natured banter about typeface or proper spacing after periods, the appellate community often argues about the right place to put citations to authority. The traditional approach places them “inline,” along with the text of the legal argument. A contrarian viewpoint, primarily advanced by Bryan Garner, argues that citations should be placed in footnotes.

Has modern technology provided a third path? Professor Rory Ryan of Baylor Law School advocates “fadecites,” reasoning:

A brief using this approach would look like this on a first read:

(A longer example is available on Professor Ryan’s Google Drive.) The reader can quickly skim over citations while reviewing the legal argument. Additionally, assuming that the court’s technology allows it, case citations can be arranged to become more visible if the reader wants to know more information. Modern .pdf technology allows a citation to become darker and more visible if the reader places the cursor on it. A hyperlink to the cited authority could also be made available.

This idea offers an ingenious solution to a recurring challenge in writing good, accessible briefs. I’d be interested in your thoughts and Professor Ryan would be as well.

A manufacturer of vaping liquid, invoking the structural limitations imposed on administrative agencies by the delegation doctrine, challenged the FDA’s power to regulate it. The Fifth Circuit observed: “The [Supreme] Court might well decide—perhaps soon—to reexamine or revive the nondelegation doctrine. But ‘[w]e are not supposed to . . . read tea leaves to predict where it might end up.'” (citation omitted). That observation was case-dispositive: “The [Supreme] Court has found only two delegations to be unconstitutional. Ever. And none in more than eighty years.” Under that precedent, Congress’s delegation of authority to the FDA in this area showed a “sufficiently intelligible principle,” constrained by Congress’s definition of “tobacco product,” and by Congress having “ma[de] many of the key regulatory decisions itself.” Big Time Vapes, Inc. v. Food & Drug Admin., No. 19-60921 (June 25, 2020).

A manufacturer of vaping liquid, invoking the structural limitations imposed on administrative agencies by the delegation doctrine, challenged the FDA’s power to regulate it. The Fifth Circuit observed: “The [Supreme] Court might well decide—perhaps soon—to reexamine or revive the nondelegation doctrine. But ‘[w]e are not supposed to . . . read tea leaves to predict where it might end up.'” (citation omitted). That observation was case-dispositive: “The [Supreme] Court has found only two delegations to be unconstitutional. Ever. And none in more than eighty years.” Under that precedent, Congress’s delegation of authority to the FDA in this area showed a “sufficiently intelligible principle,” constrained by Congress’s definition of “tobacco product,” and by Congress having “ma[de] many of the key regulatory decisions itself.” Big Time Vapes, Inc. v. Food & Drug Admin., No. 19-60921 (June 25, 2020).

Congratulations to Judge Cory Wilson of Mississippi, who was confirmed by the Senate yesterday as the newest member of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

Congratulations to Judge Cory Wilson of Mississippi, who was confirmed by the Senate yesterday as the newest member of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

A Texas business alleged that the CARES Act impermissibly discriminated against it as a bankruptcy debtor. The Fifth Circuit, citing its rule of orderliness, noted that it “has concluded that all injunctive relief directed at the [Small Business Administration] is absolutely prohibited.” Accordingly, “the bankruptcy court exceeded its authority when it issued an injunction against the SBA administrator … .” Hidalgo County Emergency Service Foundation v. Carranza, No. 20-40368 (June 22, 2020).

A Texas business alleged that the CARES Act impermissibly discriminated against it as a bankruptcy debtor. The Fifth Circuit, citing its rule of orderliness, noted that it “has concluded that all injunctive relief directed at the [Small Business Administration] is absolutely prohibited.” Accordingly, “the bankruptcy court exceeded its authority when it issued an injunction against the SBA administrator … .” Hidalgo County Emergency Service Foundation v. Carranza, No. 20-40368 (June 22, 2020).

Hoover Panel Systems contracted with HAT Contract to design a component for office desks. The Fifth Circuit found their contract ambiguous, noting the tension between its introductory and first-numbered paragraphs. While both address confidentiality, the introduction is general and paragraph 1 describes a particular process:

Hoover Panel Systems contracted with HAT Contract to design a component for office desks. The Fifth Circuit found their contract ambiguous, noting the tension between its introductory and first-numbered paragraphs. While both address confidentiality, the introduction is general and paragraph 1 describes a particular process:

“Both parties agree that all information disclosed to the other party, such as inventions, improvements, know-how, patent applications, specifications, drawings, sample products or prototypes,[]engineering data, processes, flow diagrams, software source code, business plans, product plans, customer lists, investor lists, and any other proprietary information shall be considered confidential and shall be retained in confidence by the other party.

1. Both parties agree to keep in confidence and not use for its or others benefit all information disclosed by the other party, which the disclosing party indicates is confidential or proprietary or marked with words of similar import (hereinafter INFORMATION). Such INFORMATION shall include information disclosed orally, which is reduced to writing within five (5) days of such oral disclosure and is marked as being confidential or proprietary or marked with words of similar import.”

The Court noted “[s]everal plausible interpretations” of these paragraphs:

- Different materials. “Hoover reads the opening paragraph to apply to the prototype, the primary property the confidentiality agreement was entered into to protect. Hoover argues that the first numbered paragraph applied to other information and communications that were not obviously confidential under the opening paragraph.”

- General v. specific. “HAT reads the opening paragraph to speak generally about the content of the agreement, and the first numbered paragraph to provide the specific instructions needed to put the confidentiality agreement into effect.”

- Different procedures. “[Another possible] interpretation is that under the agreement, proprietary information is automatically confidential while all other information must be marked. The opening paragraph states that “proprietary material shall be considered confidential,” and in the first numbered paragraph, “all information . . . which the disclosing party indicates is confidential or proprietary or marked with words of similar import” is considered confidential.”

- Substance v. housekeeping. “Another plausible reading is that the opening paragraph provides the scope for all information that is confidential while the first numbered paragraph functions as a housekeeping paragraph, providing instruction on how to mark information as confidential, but not requiring labeling as a condition precedent.”

Hoover Panel Systems, Inc. v. HAT Contract, Inc., No. 19-10650 (June 17, 2020).

In re Spiros Partners is the second recent mandamus opinion by the Fifth Circuit about notice in large collective actions under the Fair Labor Standards Act. The plaintiff–an exotic dancer with the stage name “Syn”–had an “Entertainer’s License Agreement” with an arbitration clause, the trial court entered an order about other parties and their agreements, and the Fifth Circuit held:

In re Spiros Partners is the second recent mandamus opinion by the Fifth Circuit about notice in large collective actions under the Fair Labor Standards Act. The plaintiff–an exotic dancer with the stage name “Syn”–had an “Entertainer’s License Agreement” with an arbitration clause, the trial court entered an order about other parties and their agreements, and the Fifth Circuit held:

- “[The district court] determined there was a genuine dispute as to the arbitration agreements’ validity and ordered Spiros to produce the names of the putative members along with their respective ELAs containing the arbitration agreements. The district court did not err by taking this step in deciding which putative members are subject to valid arbitration agreements, and thus which putative members will not receive notice.”

- “The only way a putative member with a valid arbitration agreement might receive notice is if ‘nothing in the agreement’ prohibits their participation in the collective action. We conclude the district court went too far by requiring submission of evidence regarding whether Spiros has arbitrated claims with other would-be collective members.” (citation omitted).

No. 20-50318 (June 19, 2020, unpublished).

“Mistah Kurtz — he dead.” Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness.

Spell v. Edwards presented a challenge to a COVID-19 restriction that became moot with the passage of time: “A Louisiana church and its pastor ask us enjoin stay-at-home orders restricting in-person church services to ten congregants. But there is nothing for us to enjoin. The challenged orders expired more than a month ago. That means this appeal and the related request for an injunction … are moot.” Notably, the restriction expired by its own terms, showing that it was not abandoned as a litigation tactic, and thus making inapplicable the “capable of repetition, yet evading review” exception to mootness. No. 20-30358 (June 18, 2020).

A recent article in the Baylor Law Review by Kylie Calabrese, a student of the able Rory Ryan at the Baylor Law School, provides a thorough and well-documented analysis of In re: JP Morgan Chase & Co., 915 F.3d 494 (5th Cir. 2019) and its implications for mandamus practice in the Fifth Circuit.

A recent article in the Baylor Law Review by Kylie Calabrese, a student of the able Rory Ryan at the Baylor Law School, provides a thorough and well-documented analysis of In re: JP Morgan Chase & Co., 915 F.3d 494 (5th Cir. 2019) and its implications for mandamus practice in the Fifth Circuit.

In In re Schlumberger Tech, Inc., the Fifth Circuit again held that mandamus relief can be necessary to remedy the erroneous production of privileged material. It found that no offensive-use waiver occurred when: “STC’s answer claimed only that it relied in good faith ‘on applicable law, administrative regulations, orders, interpretations and/or administrative practice or policy enforcement.’ STC did not claim that counsel advised it that its decisions complied with the FLSA. Indeed, its answer did not allude to advice of counsel at all. While privileged communications may have some bearing on STC’s beliefs about its compliance, STC has not ‘rel[ied] on attorney-client communications’ to establish its good-faith defense.” No. 20-30236 (June 4, 2020).

Last week, I noted the holding in Gulf Engineering Co. v. Dow Chemical Co. about the construction of the parties’ contract (Dow had the right, but not the obligation, to assign work to Gulf Engineering during the relevant period of time). Not surprisingly, this holding caused trouble for the plaintiff’s damages model:

Last week, I noted the holding in Gulf Engineering Co. v. Dow Chemical Co. about the construction of the parties’ contract (Dow had the right, but not the obligation, to assign work to Gulf Engineering during the relevant period of time). Not surprisingly, this holding caused trouble for the plaintiff’s damages model:

“… The only evidence of how the details of daily or weekly assignments can be known is that Dow used oral and written communication that included the issuing of work orders and job schedules. What Gulf needed to offer were details about any assigned work. That would include evidence of such variables as the nature of the work, the number of employees needed, and the number of days needed to complete the work. In other words, what was needed in some form was evidence relevant to allow a calculation of what Dow would have paid and what Gulf’s expenses would have been, i.e., what Gulf’s profit would have been. Instead, the only evidence was an average from an historic time period, where all those variables were blended.

As we explained earlier, the evidence of any assigned work after the notice of termination barely suffices to show liability. For us then to allow the evidence offered of daily-average profits over one or five years to substitute for actual profits for actual assigned work is a bridge too far. …”

No. 19-30395 (June 9, 2020) (emphasis added).

The contract-interpretation question in Gulf Engineering Co. v. Dow Chemical Co. was whether, after giving notice of termination, Dow Chemical was obligated to provide work to Gulf Engineering for another 90 days, or whether Dow had the “right but no contracted-for obligation to continue assigning work to Gulf.”

The Fifth Circuit found that the contract unambiguously meant that Dow had the right but not the obligation to give work to Gulf, and that the trial court thus erred in denying Dow’s summary-judgment motion on that point. The Court further found that the district court “compounded the error” by instructing the jury that it had found the relevant contract term to be ambiguous. Nevertheless, the error was harmless because the trial court also gave an instruction about the contract that substantially agreed with Dow’s reading of it. No. 19-30395 (June 9, 2020).

Despite the complexity of a dispute about telecommunication regulations, the parties’ performance mattered: “Sprint and Verizon’s conduct, while certainly not dispositive, is nevertheless informative. Sprint and Verizon are among America’s largest IXCs and are sophisticated market participants. Yet, they waited more than eighteen years to object to the LECs’ access charges for intraMTA wireless-to-wireline calls, paying hundreds of millions of dollars in the process. Moreover, over that same timeframe, Sprint’s and Verizon’s LEC affiliates imposed access charges on IXCs, including on each other, for intraMTA wireless-to-wireline calls. We decline to award Sprint and Verizon, who sat on their hands for the better part of two decades, a nine-figure windfall based on an interpretation of § 251(g) that is divorced from both the 1996 Act’s text and industry practice.” No. 18-10768 (May 27, 2020). (LPCH was one of the counsel for the prevailing side of this case.)

Despite the complexity of a dispute about telecommunication regulations, the parties’ performance mattered: “Sprint and Verizon’s conduct, while certainly not dispositive, is nevertheless informative. Sprint and Verizon are among America’s largest IXCs and are sophisticated market participants. Yet, they waited more than eighteen years to object to the LECs’ access charges for intraMTA wireless-to-wireline calls, paying hundreds of millions of dollars in the process. Moreover, over that same timeframe, Sprint’s and Verizon’s LEC affiliates imposed access charges on IXCs, including on each other, for intraMTA wireless-to-wireline calls. We decline to award Sprint and Verizon, who sat on their hands for the better part of two decades, a nine-figure windfall based on an interpretation of § 251(g) that is divorced from both the 1996 Act’s text and industry practice.” No. 18-10768 (May 27, 2020). (LPCH was one of the counsel for the prevailing side of this case.)

Phoneternet complained that an inaccurate report available on Lexis-Nexis caused the loss of a business opportunity (oddly enough, with the car company Lexus). The Fifth Circuit affirmed, holding (among other matters) as to their negligent-misrepresentation and promissory-estoppel claims:

“If Phoneternet believed the errors had already been corrected, there would have been no reason for Phoneternet to repeatedly call LexisNexis. In that case, Phoneternet would be asking LexisNexis to correct already accurate information. Moreover, to the extent Phoneternet did rely on LexisNexis’s alleged statement that all fifteen errors in the report had been “modified . . . as requested,” such reliance cannot be considered reasonable and justified. Given the alleged importance of this report—the only remaining obstacle between Phoneternet and a lucrative multimillion-dollar contract with Toyota—Phoneternet should have at least confirmed that the errors had been corrected before blindly relying on LexisNexis’s representation.”

Phoneternet LLC v. Lexis-Nexis, No. 19-11194 (June 3, 2020) (unpublished) (emphasis added).

Hewlett-Packard proved $176 million in antitrust damages at trial (later trebled); the defendant argued that HP had not proved it was a direct purchaser of the optical drives at issue. The Fifth Circuit affirmed. On the two key points, it held:

Hewlett-Packard proved $176 million in antitrust damages at trial (later trebled); the defendant argued that HP had not proved it was a direct purchaser of the optical drives at issue. The Fifth Circuit affirmed. On the two key points, it held:

- Expert testimony. Under the proper standard of review, this testimony by HP’s damages expert sufficed: “[W]e did quite a lot of work to understand the data that we received; and it was my understanding, based on that work, that the data was purchases by the plaintiff HP, Inc. formerly known as Hewlett-Packard Company. . . . In the data files that I received, the transactions identified the supplier; and in any cases in which the supplier was identified as an HP entity, I excluded those . . . . ”

- Fact testimony. Any uncertainty in the following testimony by an HP executive was not enough to unseat the above-quoted expert conclusion:

Q. And so in a procurement event you have an ODD supplier and a purchaser, an entity that purchases. Did HP, Inc. . . . was that the purchaser in all of these procurement events that you have described?

A. It was some form of HP. I don’t know that it was HP, Inc., but it was a legal entity of HP, somewhere in the region that these were purchased, that purchased the drives.

A. It was some form of HP. I don’t know that it was HP, Inc., but it was a legal entity of HP, somewhere in the region that these were purchased, that purchased the drives.

Q. So the purchaser might not have been HP, Inc. at a particular procurement event? It might have been some subsidiary of HP, Inc.?

A. It could well have been, yes. . . . I’m not exactly sure on how that was spread out, but it could very well have been.

Hewlett-Packard Co. v. Quanta Storage, No. 19-20799 (June 5, 2020). A longer version of this post appears in the Texas Lawbook.

Here is the PowerPoint for my June 2 presentation to the DBA’s Appellate Law Section about Fifth Court commercial-litigation opinions over the last twelve months.

Here is the PowerPoint for my June 2 presentation to the DBA’s Appellate Law Section about Fifth Court commercial-litigation opinions over the last twelve months.

The Fifth Court rejected Burford abstention in Stratta v. Roe, observing: “Burford ‘does not require abstention whenever there exists [complex state administrative processes], or even in all cases where there is a potential for conflict with state regulatory law or policy.’ Nor would a federal judgment here interfere with the coherence of state policy. [Groundwater Conservation Districts] are designed to be decentralized and fragmentary in order to offer local control over groundwater resources. There are roughly 100 GCDs in Texas, but nearly two-thirds of them oversee territory coextensive with a single county.” No. 18-50994-CV (May 29, 2020) (citation omitted).

The Fifth Court rejected Burford abstention in Stratta v. Roe, observing: “Burford ‘does not require abstention whenever there exists [complex state administrative processes], or even in all cases where there is a potential for conflict with state regulatory law or policy.’ Nor would a federal judgment here interfere with the coherence of state policy. [Groundwater Conservation Districts] are designed to be decentralized and fragmentary in order to offer local control over groundwater resources. There are roughly 100 GCDs in Texas, but nearly two-thirds of them oversee territory coextensive with a single county.” No. 18-50994-CV (May 29, 2020) (citation omitted).

Recent orders about conducting trials during the pandemic highlight the different procedural structures of the state and federal courts.

Recent orders about conducting trials during the pandemic highlight the different procedural structures of the state and federal courts.

In the state system, the Texas Supreme Court recently released its seventeenth emergency order about when and how jury trials may resume. (An order, incidentally, that I got from the txcourts.gov website, which shows progress in returning that site to normal after the recent hacker attack.)

In the federal system, the recent order in In re Tanner reminds of the considerable district court discretion about such matters: “[T]he district court has given great consideration to the COVID-19 issues addressed by Tanner. . . . [W]hatever each of us as judges might have done in the same circumstance is not the question. Instead, as cited below, the standards are much higher for evaluating the district court’s decision” for purposes of a writ of mandamus or prohibition. No. 20-10510 (May 29, 2020).

On June 2 at 2 PM, as a guest of the DBA’s Appellate Law Section, I’ll review several Dallas Court of Appeals opinions in commercial cases since June of last year, when I made a similar presentation. This one will be online, so please register in advance on the DBA’s website! The PowerPoint will be posted after the presentation.

On June 2 at 2 PM, as a guest of the DBA’s Appellate Law Section, I’ll review several Dallas Court of Appeals opinions in commercial cases since June of last year, when I made a similar presentation. This one will be online, so please register in advance on the DBA’s website! The PowerPoint will be posted after the presentation.

The original party to an oilfield-services agreement assigned its rights to Motis Energy. Motis sued on the agreement, lost, and sought to avoid the agreement’s attorneys-fee provision. The Fifth Circuit ruled against it: “Motis is a nonparty to the Agreement. But Motis embraced the Agreement by seeking to enforce its terms. Motis’s argument–that it did not embrace the entirety of the Agreement because it was assigned the right to Motis-DI’s claims, not the entire contract–lacks merit. When a plaintiff sues to enforce a contract to which it was not a party, the Supreme Court of Texas has held, as have we, that the plaintiff subjects itself to the entirety of the contract terms.” Motis Energy LLC v. SWN Prod. Co. LLC, No. 19-20495 (April 28, 2020) (unpublished) (emphasis added).

The original party to an oilfield-services agreement assigned its rights to Motis Energy. Motis sued on the agreement, lost, and sought to avoid the agreement’s attorneys-fee provision. The Fifth Circuit ruled against it: “Motis is a nonparty to the Agreement. But Motis embraced the Agreement by seeking to enforce its terms. Motis’s argument–that it did not embrace the entirety of the Agreement because it was assigned the right to Motis-DI’s claims, not the entire contract–lacks merit. When a plaintiff sues to enforce a contract to which it was not a party, the Supreme Court of Texas has held, as have we, that the plaintiff subjects itself to the entirety of the contract terms.” Motis Energy LLC v. SWN Prod. Co. LLC, No. 19-20495 (April 28, 2020) (unpublished) (emphasis added).

Katherine P. v Humana Health Plan, an ERISA dispute about hospitalization to treat an eating disorder, turned on a specific criterion: whether “[t]reatment at a less intense level of care has been unsuccessful in controlling” the disorder. The Fifth Circuit found a fact issue, noting:

Katherine P. v Humana Health Plan, an ERISA dispute about hospitalization to treat an eating disorder, turned on a specific criterion: whether “[t]reatment at a less intense level of care has been unsuccessful in controlling” the disorder. The Fifth Circuit found a fact issue, noting:

“[T]here is evidence in the administrative record that suggests Katherine P. satisfied that requirement. For example, in her last appeal Humana, Katherine P. provided a declaration describing her history of failed treatment. In it, she listed past failed treatment regimens, including outpatient treatment. Her mother likewise provided a declaration making essentially the same point. Furthermore, Katherine P.’s physicians said she was ‘unable to follow a weight gain meal plan and to abstain from symptoms of purging and restricting while she was at a lower level of care.’”

(citations omitted). The court also noted evidence cutting the other way:

Her same declaration, for example, shows that she participated in an eight-week intensive outpatient program in late 2010 that failed due to external trauma—not because the treatment was ineffective. And Humana noted that the 2010 treatment was her most recent course of treatment prior to her admittance to Oliver-Pyatt about a year and a half later. A factfinder could therefore conclude that Katherine P. failed to show that she met [the criterion].

Katherine P. v Humana Health Plan, No. 19-50276 (May 14, 2020).

The COVID-19 crisis has required the courts to deftly juggle conflicting, and important, interests when asked to review emergency regulation. A good summary of such a balancing exercise appears in First Pentecostal Church of Holly Springs v. City of Holly Springs: “Our sole appellate jurisdiction in this case rests upon denial of an injunction implied from the choice by the district court not to rule in an expedited fashion. After briefing, it remains plain that the court is being requested to enjoin a shifting regulatory regime not yet settled as to its regulation and regulatory effect, such as the apparent acceptance by the Church of the Governor’s regulations. That settlement is best made by the district court in the first instance. Lest we in error step upon treasured values of religious freedom and personal liberties we stay our hand and return this case to the district court for decision footed upon a record reflecting current conditions.” No. 20-60399 (May 22, 2020) (emphasis added).

The COVID-19 crisis has required the courts to deftly juggle conflicting, and important, interests when asked to review emergency regulation. A good summary of such a balancing exercise appears in First Pentecostal Church of Holly Springs v. City of Holly Springs: “Our sole appellate jurisdiction in this case rests upon denial of an injunction implied from the choice by the district court not to rule in an expedited fashion. After briefing, it remains plain that the court is being requested to enjoin a shifting regulatory regime not yet settled as to its regulation and regulatory effect, such as the apparent acceptance by the Church of the Governor’s regulations. That settlement is best made by the district court in the first instance. Lest we in error step upon treasured values of religious freedom and personal liberties we stay our hand and return this case to the district court for decision footed upon a record reflecting current conditions.” No. 20-60399 (May 22, 2020) (emphasis added).

I spoke today, virtually, to the Texas Bar CLE’s 33rd “Advanced Evidence and Discovery Course,” which would have been in San Antonio. My topic was proving up damages in a commercial case, and I focused on ten specific issues identified in recent Texas and Fifth Circuit cases. I also showed off some smooth hand gestures, as you can see above. Here is a copy of my PowerPoint. The Bar staff did a terrific job with the A/V logistics and I look forward to doing another program with them soon.

I spoke today, virtually, to the Texas Bar CLE’s 33rd “Advanced Evidence and Discovery Course,” which would have been in San Antonio. My topic was proving up damages in a commercial case, and I focused on ten specific issues identified in recent Texas and Fifth Circuit cases. I also showed off some smooth hand gestures, as you can see above. Here is a copy of my PowerPoint. The Bar staff did a terrific job with the A/V logistics and I look forward to doing another program with them soon.

In long-running litigation about liability for hotel occupancy taxes, the Fifth Circuit’s prior mandate said that “plaintiff-appellee cross-appellant pay to defendants-appellants cross appellees the costs on appeal to be taxed by the Clerk of this Court.” The Court held that this language did not preclude the trial court clerk from assessing appropriate costs on remand pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 39(e).

In long-running litigation about liability for hotel occupancy taxes, the Fifth Circuit’s prior mandate said that “plaintiff-appellee cross-appellant pay to defendants-appellants cross appellees the costs on appeal to be taxed by the Clerk of this Court.” The Court held that this language did not preclude the trial court clerk from assessing appropriate costs on remand pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 39(e).

The Court also held: “The fact that the decretal language in the first appeal used the word ‘vacated’ instead of ‘reversed’ does not change this result. . . . While an argument can be made that ‘reversed’ might have been the better choice for the decretal language in the first appeal, what matters for purposes of Rule 39(a) is the substance of the disposition, not merely the form.” San Antonio v. Hotels.com, No. 19-50701 (May 11, 2020) (citations omitted, emphasis in original).

PRACTICE TIP: Fed. R. App. P. 39(e)(3) includes “premiums paid for a bond or other security to preserve rights pending appeal” as a taxable cost–in this litigation, a cost exceeding $2 million.

Despite the May 11 en banc opinion about the “finality trap,” the plaintiff in CBX Resources v. ACE Am. Ins. Co. remained stuck in the trap after dismissing certain of its claims – against the sole defendant – without prejudice: “To be sure, many cases applying the Ryan rule have multiple defendants, one or more of which was dismissed without prejudice while at least one defendant prevailed on the merits. But Ryan itself was an employment dispute with a single plaintiff suing a single defendant, his employer.” No. 18-50740 (May 12, 2020).

Despite the May 11 en banc opinion about the “finality trap,” the plaintiff in CBX Resources v. ACE Am. Ins. Co. remained stuck in the trap after dismissing certain of its claims – against the sole defendant – without prejudice: “To be sure, many cases applying the Ryan rule have multiple defendants, one or more of which was dismissed without prejudice while at least one defendant prevailed on the merits. But Ryan itself was an employment dispute with a single plaintiff suing a single defendant, his employer.” No. 18-50740 (May 12, 2020).

The “finality trap” can arise when a plaintiff sues two defendants and then (a) voluntarily dismisses one defendant without prejudice, and then (b) litigates to conclusion against the other and loses. The plaintiff’s ability to appeal the outcome of proceeding (b) is affected by the lack of a final judgment in proceeding (a), because under Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(b), there is not a final decision as to any one defendant until there is a final decision for all defendants

The “finality trap” can arise when a plaintiff sues two defendants and then (a) voluntarily dismisses one defendant without prejudice, and then (b) litigates to conclusion against the other and loses. The plaintiff’s ability to appeal the outcome of proceeding (b) is affected by the lack of a final judgment in proceeding (a), because under Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(b), there is not a final decision as to any one defendant until there is a final decision for all defendants

Williams v. Seidenbach found that entry of a partial final judgment under Rule 54(b) solved the plaintiffs’ problem in that case. (Judge Ho, joined by Chief Judge Owen and Judges Jones, Stewart, Dennis, Elrod, Haynes, Graves, Higginson, and Engelhardt).

A concurrence suggested that future litigants consider “bindingly disclaiming their right to reassert any dismissed-without-prejudice claims” as way to solve the problem. (Judge Willett, joined by Judge Southwick) (Note that all opinions appear in the same PDF document, linked above).

A concurrence suggested that future litigants consider “bindingly disclaiming their right to reassert any dismissed-without-prejudice claims” as way to solve the problem. (Judge Willett, joined by Judge Southwick) (Note that all opinions appear in the same PDF document, linked above).

A dissent, focused on the text of Rules 41 and 54, observed that once a “Rule 41(a) dismissal ‘adjudicated’ the plaintiffs’ claims . . . there were no claims pending after that adjudication” which mean that “Rule 54(b) was (and still is) completely irrelevant.” (Judge Oldham, joined by Judges Smith, Duncan and – unexpectedly – Costa).

To be continued . . .

O’Shaughnessy v. Young Living Essential Oils presents the classic contract-law problem of an agreement contained in more than one document; here, it led to the Fifth Circuit rejecting the defendant’s effort to compel arbitration. O’Shaughnessey’s “Member Agreement” with Young Living had three salient features:

O’Shaughnessy v. Young Living Essential Oils presents the classic contract-law problem of an agreement contained in more than one document; here, it led to the Fifth Circuit rejecting the defendant’s effort to compel arbitration. O’Shaughnessey’s “Member Agreement” with Young Living had three salient features:

- A “Jurisdiction and Choice of Law” clause – “The Agreement will be interpreted and construed in accordance with the laws of the State of Utah applicable to contracts to be performed therein. Any legal action concerning the Agreement will be brought in the state and federal courts located in Salt Lake City, Utah.”

- A merger clause – “The Agreement constitutes the entire agreement between you and Young Living and supersedes all prior agreements; and no other promises,

representations, guarantees, or agreements of any kind will be valid unless in writing and signed by both parties.” - And it incorporated by reference a “Policies and Procedures” document.

The Policies and Procedures, in turn, had an arbitration clause with a carve-out for certain kinds of injunctive relief. The Court held: “The arbitration clause’s exemption of certain litigatory rights from its purview does not cure its inherent conflict with the Jurisdiction and Choice of Law provision. The two provisions irreconcilably conflict and for this reason, we agree that there was no ‘meeting of the minds’ with respect to arbitration in this case.” No. 19-51169 (April 28, 2020). (The above picture, BTW, is Mary Astor playing Brigid O’Shaughnessey in 1941’s The Maltese Falcon.)

With the kids home from school because of the coronavirus, I’ve watched a lot of YouTube videos over their shoulders. In particular, this one tells the fascinating story about how post-production editing saved Star Wars, which was bloated and impossible to follow in its first rough versions. Among

With the kids home from school because of the coronavirus, I’ve watched a lot of YouTube videos over their shoulders. In particular, this one tells the fascinating story about how post-production editing saved Star Wars, which was bloated and impossible to follow in its first rough versions. Among  other changes, the start of the film was drastically simplified – from a series of back-and-forths between space and Tatooine, to a focus on the opening space battle and no shots of Tatooine until the droids landed there. This bit of editing is directly relevant to the tendency of legal writers to “define” (introduce) all characters and terms at the beginning of their work, without regard to the flow of the narrative that follows.

other changes, the start of the film was drastically simplified – from a series of back-and-forths between space and Tatooine, to a focus on the opening space battle and no shots of Tatooine until the droids landed there. This bit of editing is directly relevant to the tendency of legal writers to “define” (introduce) all characters and terms at the beginning of their work, without regard to the flow of the narrative that follows.

In affirming a preliminary injunction in a noncompete case, Realogy Holdings Corp. v. Jongeblood suggested that the district court could “when determining the term of any injunction, to reweigh the equities . . . in light of the time that has passed during the pendency of th[e] appeal.” Interestingly, this suggestion came after the Fifth Circuit had granted a stay during the preliminary-injunction appeal, which it also expedited. Specifically, the relevant covenants last for a year, the injunction was granted on November 15, 2019; the appellate stay was granted on January 24, 2020, and the opinion issued on April 27. No. 19-20864.

In affirming a preliminary injunction in a noncompete case, Realogy Holdings Corp. v. Jongeblood suggested that the district court could “when determining the term of any injunction, to reweigh the equities . . . in light of the time that has passed during the pendency of th[e] appeal.” Interestingly, this suggestion came after the Fifth Circuit had granted a stay during the preliminary-injunction appeal, which it also expedited. Specifically, the relevant covenants last for a year, the injunction was granted on November 15, 2019; the appellate stay was granted on January 24, 2020, and the opinion issued on April 27. No. 19-20864.