I recently wrote an article, “Federalism and Appellate Procedure: Five Texas-Federal Differences to Know,” in the Appellate Advocate, the quarterly publication by the Appellate Section of the State Bar of Texas. I hope you find it interesting and useful.

Category Archives: General Court Information

The fantastically controversial Texas abortion statute returned to the Fifth Circuit, which granted an administrative stay on Friday, October 8, while it receives further briefing about a stay during the appeal of Judge Pittman’s preliminary-injunction order. Enthusiasts of court history will note that the motions panel —

bears substantial similarity to the original panel in what led to the 2021 Supreme Court opinion in Collins v. Yellen. The panel divided 2-1 (Judges Haynes and Stewart, joining) about the constitutional problem with Fannie Mae’s regulator, and then again divided 2-1 (Judges Haynes and Willett, joining) about the proper remedy:

bears substantial similarity to the original panel in what led to the 2021 Supreme Court opinion in Collins v. Yellen. The panel divided 2-1 (Judges Haynes and Stewart, joining) about the constitutional problem with Fannie Mae’s regulator, and then again divided 2-1 (Judges Haynes and Willett, joining) about the proper remedy:

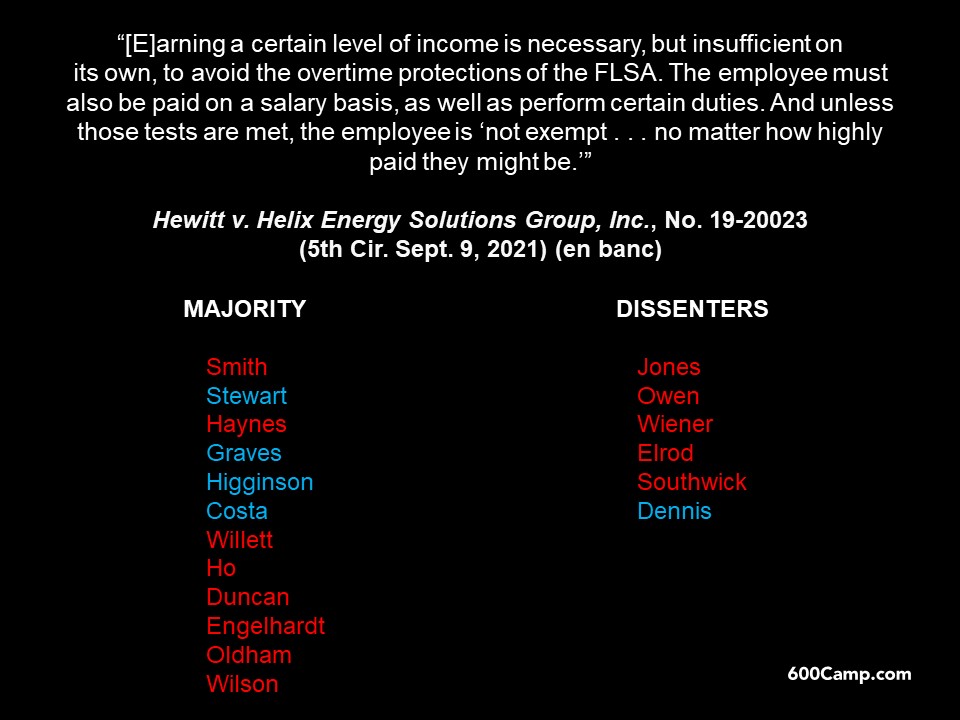

The en banc court divided along atypical lines in Hewitt v. Helix Energy, a dispute about overtime-pay obligations for highly compensated employees in the oil-and-gas industry. The Texas Lawbook and Houston Chronicle have covered the opinion thoroughly; below is a chart showing which judges joined the majority opinion and which judges dissented in some way. Note that Senior Judge Wiener participated in this en banc case because he was part of the original panel.

Longtime observers of the Court may see echoes of the divided en banc court in Mississippi Poultry Ass’n v. Madigan, 31 F.3d 293 (5th Cir. 1994) (en banc), a dispute about the import of the word “same” in the Poultry Products Inspection Act.

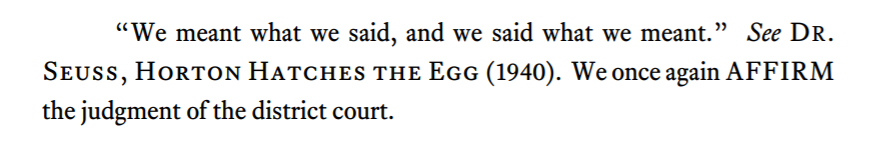

Counsel failed to file a summary-judgment response because his notification of filing went to his email “spam” folder. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the denial of relief under Fed. R. Civ. P. 59(e):

Counsel failed to file a summary-judgment response because his notification of filing went to his email “spam” folder. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the denial of relief under Fed. R. Civ. P. 59(e):

“It is not ‘manifest error to deny relief when failure to file was within [Rollins’s] counsel’s ‘reasonable control.’ Notice of Home Depot’s motion for summary judgment was sent to the email address that Rollins’s counsel provided. Rule 5(b)(2)(E) provides for service ‘by filing [the pleading] with the court’s electronic-filing system’ and explains that ‘service is complete upon filing or sending.’ That rule was satisfied here. Rollins’s counsel was plainly in the best position to ensure that his own email was working properly—certainly more so than either the district court or Home Depot. Moreover, Rollins’s counsel could have checked the docket after the agreed deadline for dispositive motions had already passed.”

Rollins v. Home Depot USA, No. 20-50736 (Aug. 9, 2021).

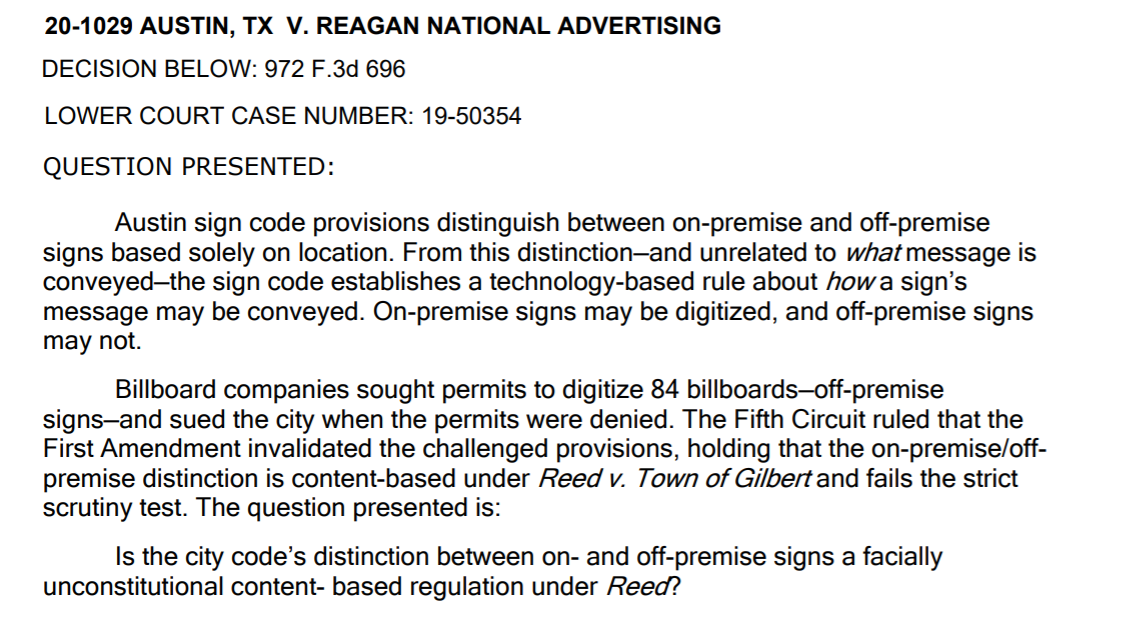

The Supreme Court will review Reagan National Advertising v. City of Austin, 972 F.3d 696 (5th Cir. 2020). The court’s summary of the issue presented is below, and here is my discussion of the case on the Coale Mind podcast —

Strong feelings were voiced about the Fifth Circuit’s panel opinion in Ramirez v. Guardarrama, 844 F. App’x 710 (5th Cir. 2021) (per curiam). The vote against en banc review was 13-4, with several opinions:

- Judge Jolly, who had been on the panel that found no Fourth Amendment violation, concurred with denial and observed: “The unanimous panel opinion also explains why we cannot quarterback from our Delphic shrines, three years later, the split-second decision making required of these officers in response to a suicidal man (1) doused in gasoline, (2) reportedly high on methamphetamine, (3) screaming nonsense, (4) holding a lighter, and (5) threatening to set himself on fire and to burn down the home, occupied by six people, which he had earlier covered in gasoline.”

- Judge Ho, joined by Judges Jolly and Jones, concurred and further observed: “[H]ow can a constitutional violation be ‘obvious,’ ‘egregious,’ and ‘conscience-shocking,’ when the dissent can’t tell the officers what they should have done differently to keep people safe?”

- Judge Oldham (also on the panel), joined by all of the above and Judge Engelhardt, reviewed the Fourth Amendment claim through a Twombly lens and concluded: “[T]he Fourth Amendment is not an antidote to tragedy. It’s a cornerstone of our Bill of Rights, with an august history and profound original meaning. We cheapen it when we treat it like a chapter from Prosser & Keeton. And we transmogrify it beyond recognition when we say officers act ‘unreasonably’ without any effort to say what a reasonable officer would’ve done.”

- Judge Smith dissented, arguing that this case provided an opportunity to revisit another recent en banc opinion.

- Judge Willett dissented, joined by Judges Graves and Higginson, pointing to recent Supreme Court cases that rejected qualified-immunity claims and observing: “The complaint alleges a plausible Fourth Amendment violation, and an obvious one at that. How is it reasonable—more accurately, not plausibly unreasonable—to set someone on fire to prevent him from setting himself on fire?”

The Supreme Court reversed a Fifth Circuit panel opinion about the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act, finding that none of the plaintiffs had standing in light of (1) the repeal of coverage-related penalties and (2) the apparent mismatch between the ACA provisions complained of as unconstitutional, and those that caused the complained–of harms to the states. California v. Texas, No. 19-840 (U.S. Jun 17, 2021) (reversing Texas v. United States, 945 F. 3d 355 (5th Cir. 2019)).

While this is a post about Texas state practice, I am cross-posting it from 600Commerce because it is of broad general interest to civil appellate practitioners.

With respect to court orders and judgments, the words “signed,” “rendered,” and “entered” are often used interchangeably. But those words have specific, technical meanings, and it is wise to remember those meanings when differences matter. Accord, Burrell v. Cornelius, 570 S.W.2d 382, 384 (Tex. 1978) (“Judges render judgment; clerks enter them on the minutes. … The entry of a judgment is the clerk’s record in the minutes of the court. ‘Entered’ is synonymous with neither ‘Signed’ nor ‘Rendered.’”).

Two rules set the background as to when critical countdowns commence:

- Tex. R. Civ. P. 306a: “The date of judgment or order is signed as shown of record shall determine the beginning of the periods prescribed by these rules for the court’s plenary power to grant a new trial or to vacate, modify, correct or reform a judgment or order and for filing in the trial court the various documents that these rules authorize a party to file …”

- Similarly, Tex. R. App. P. 26.1 begins: “The notice of appeal must be filed within 30 days after the judgment is signed, except as follows …”

By contrast, “[j]udgment is rendered when the trial court officially announces its decision in open court or by written memorandum filed with the clerk.” E.g., S&A Restaurant Corp. v. Leal, 892 S.W.2d 855, 857 (Tex. 1995) (per curiam). And the above-quoted paragraph from Rule 306a concludes: “… but this rule shall not determine what constitutes rendition of a judgment or order for any other purpose.”

By contrast, entry of judgment refers to the recording of a rendered judgment in the court’s official records. See, e.g., Lone Star Cement Corp v. Fair, 467 S.W.2d 402, 405 (Tex. 1971) (“The law is settled in this state that clerical errors in the entry of a judgment, previously rendered, may be corrected after the end of the court’s term by a nunc pro tunc judgment; however, judicial errors in the previously rendered judgment may not be so corrected.” (emphasis added)).

I gratefully acknowledge the excellent insights of Ben Taylor in preparing this post!

The Supreme Court affirmed the Fifth Circuit’s analysis of appellate costs (often a trivial issue, but here involving over $2 million in supersedeas-bond premiums) in City of San Antonio v. Hotels.com, stating: “[W]e hold that courts of appeals have the discretion to apportion all the appellate costs covered by Rule 39 and that district courts cannot alter that allocation.” No. 20–334 (U.S. May 27, 2021). (It remains to be seen how the Roberts Court will review other, more politically charged opinions from the Fifth Circuit this term.)

Please sign up for my Fifth Circuit update for the Austin Bar Association this Thursday, May 12, at noon – here is the link – and Texas Solicitor General Judd Stone will present a Supreme Court update as well! Here is a draft of my PowerPoint for the presentation.

Roe v. Wade famously named Dallas County DA Henry Wade (right) as its defendant, because he was the official charged with enforcement of the criminal statute at issue. The Texas Legislature has passed a new abortion law — a “heartbeat bill” — that features a novel enforcement procedure involving private litigants. The statute disclaims any

Roe v. Wade famously named Dallas County DA Henry Wade (right) as its defendant, because he was the official charged with enforcement of the criminal statute at issue. The Texas Legislature has passed a new abortion law — a “heartbeat bill” — that features a novel enforcement procedure involving private litigants. The statute disclaims any  public enforcement, relying on a private right of action against abortion providers that features an extremely broad definition of standing. The Texas Tribune correctly notes that the Fifth Circuit’s en banc opinion in Okpalobi v. Foster, 244 F.3d 501 (5th Cir. 2001), declined to extend Ex Parte Young (left) to a Louisiana statute that created a somewhat-analogous private cause of action against abortion providers. Assuming that the Governor signs the new Texas law, Okpalobi will likely be cited frequently in federal-court challenges to it. (I recently did a an interview with Fox 4’s “Good Day” about this new law.)

public enforcement, relying on a private right of action against abortion providers that features an extremely broad definition of standing. The Texas Tribune correctly notes that the Fifth Circuit’s en banc opinion in Okpalobi v. Foster, 244 F.3d 501 (5th Cir. 2001), declined to extend Ex Parte Young (left) to a Louisiana statute that created a somewhat-analogous private cause of action against abortion providers. Assuming that the Governor signs the new Texas law, Okpalobi will likely be cited frequently in federal-court challenges to it. (I recently did a an interview with Fox 4’s “Good Day” about this new law.)

In 2017, the USS Fitzgerald, a U.S. Navy destroyer, collided with the MV ACX Crystal, a commercial container ship, in Japanese territorial waters. The incident caused extensive damage and injury, including the death of seven American sailors. Relatives of the deceased sailors sued the ship owner in federal court under the Death on the High Seas Act. They based personal jurisdiction on Fed. R. Civ. P. 4(k)(2), “alleging that, despite NYK Line’s status as a foreign corporation, its substantial, systematic, and continuous contacts with the United States should make NYK Line amenable to suit in federal court.” I

In 2017, the USS Fitzgerald, a U.S. Navy destroyer, collided with the MV ACX Crystal, a commercial container ship, in Japanese territorial waters. The incident caused extensive damage and injury, including the death of seven American sailors. Relatives of the deceased sailors sued the ship owner in federal court under the Death on the High Seas Act. They based personal jurisdiction on Fed. R. Civ. P. 4(k)(2), “alleging that, despite NYK Line’s status as a foreign corporation, its substantial, systematic, and continuous contacts with the United States should make NYK Line amenable to suit in federal court.” I

In Douglass v. Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha, the Fifth Circuit noted that that the case raised novel but significant issues about the distinction between 5th and 14th Amendment due process protections, but found itself constrained by the “rule of orderliness” to follow an earlier Circuit case on the topic. A 2-judge dissent urged en banc consideration, noting that “[o]ur decision today … determines that a global corporation with extensive contacts with the United States cannot be haled into federal court for federal claims arising out of a maritime collision that killed seven United States Navy sailors.” No. 20-30379 (April 30, 2021).

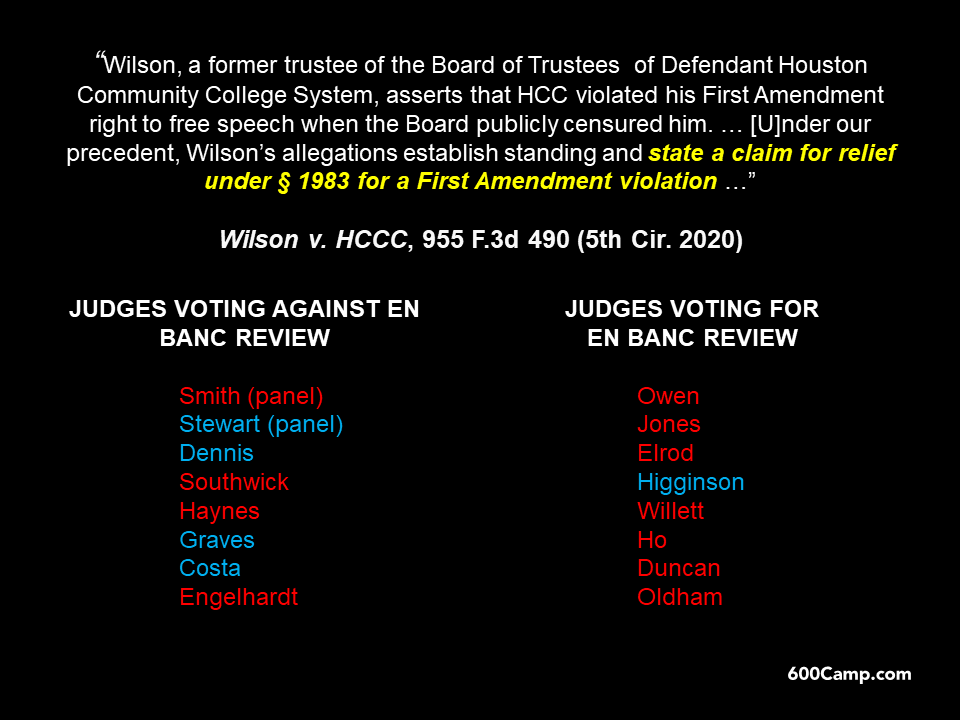

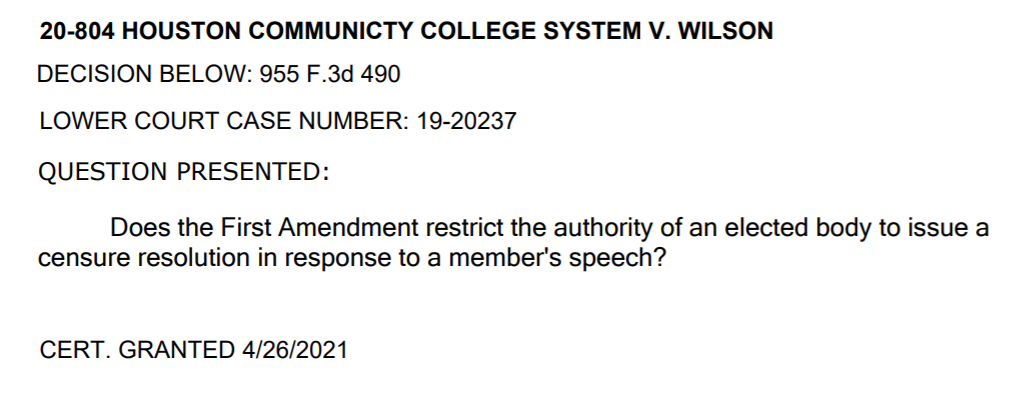

The difficult First Amendment case of Wilson v. Harris County Community College System, 955 F.3d 490 (5th Cir. 2020), produced a panel opinion that allowed an elected member of a community-college board to bring a claim about alleged retaliation for his exercise of First Amendment rights, followed by an 8-8 tie on the question of en banc review. The Supreme Court has now granted review of this fundamental issue about the relationship between elected officials’ rights and the interests of the institutions they serve:  (The first episode of the “Coale Mind” podcast considers this case along with the “Cancel Culture” phenomenon.)

(The first episode of the “Coale Mind” podcast considers this case along with the “Cancel Culture” phenomenon.)

The full Fifth Circuit declined to grant en banc review to State of Texas v. Rettig, 987 F.3d 518 (5th Cir. 2021), which involved constitutional challenges by certain states to two aspects of the Affordable Care Act. They contended that the “Certification Rule” violated the nondelegation doctrine, and that section 9010 of the ACA violated the Spending Clause and the Tenth Amendment’s doctrine of intergovernmental tax immunity. The panel found the laws constitutional, in an opinion by Judge Haynes that was joined by Judges Barksdale and Willett. “In the en banc poll, five judges voted in favor of rehearing (Judges Jones, Smith, Elrod, Ho, and Duncan), and eleven judges voted against rehearing (Chief Judge Owen, and Judges Stewart, Dennis, Southwick, Haynes, Graves, Higginson, Costa, Willett, Engelhardt, and Wilson),” with Judge Oldham not participating, and the five pro-rehearing judges joining a dissent.

The full Fifth Circuit declined to grant en banc review to State of Texas v. Rettig, 987 F.3d 518 (5th Cir. 2021), which involved constitutional challenges by certain states to two aspects of the Affordable Care Act. They contended that the “Certification Rule” violated the nondelegation doctrine, and that section 9010 of the ACA violated the Spending Clause and the Tenth Amendment’s doctrine of intergovernmental tax immunity. The panel found the laws constitutional, in an opinion by Judge Haynes that was joined by Judges Barksdale and Willett. “In the en banc poll, five judges voted in favor of rehearing (Judges Jones, Smith, Elrod, Ho, and Duncan), and eleven judges voted against rehearing (Chief Judge Owen, and Judges Stewart, Dennis, Southwick, Haynes, Graves, Higginson, Costa, Willett, Engelhardt, and Wilson),” with Judge Oldham not participating, and the five pro-rehearing judges joining a dissent.

Several years ago, mathematicians rejoiced at the mapping of the world’s most complex structure, the 248-dimension “Lie Group E8” (right). Not to be outdone, the en banc Fifth Circuit has issued Brackeen v. Haaland, a 325-page set of opinions about the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act–a work so complicated that a six-page per curiam introduction is needed to explain the Court’s divisions on the issues. No. 18-11479 (April 6, 2021). The splits, opinions, and holdings will be reviewed in future posts.

Several years ago, mathematicians rejoiced at the mapping of the world’s most complex structure, the 248-dimension “Lie Group E8” (right). Not to be outdone, the en banc Fifth Circuit has issued Brackeen v. Haaland, a 325-page set of opinions about the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act–a work so complicated that a six-page per curiam introduction is needed to explain the Court’s divisions on the issues. No. 18-11479 (April 6, 2021). The splits, opinions, and holdings will be reviewed in future posts.

The DC Circuit’s recent style manual amendment that criticized the use of “Garamond” font has drawn national attention. As this matter has now become a pressing issue facing the federal courts, 600Camp weighs in with these thoughts, all of which are written in 14-point size:

Accordingly, if you really like Garamond and are writing a brief with a word limit rather than a page limit, you should consider bumping the size up to 15-point. And of course, in a jurisdiction with page limits rather than word limits, Garamond offers a way to add more substance to your submission–but be careful that this extra substance does not come at the price of less visibility.

Recent orders set these matters for en banc reconsideration:

US v. Dubin, in which the panel held: “An issue of first impression for our court is whether David Dubin’s fraudulently billing Medicaid for services not rendered constitutes an illegal ‘use’ of ‘a means of identification of another person’, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1028A.”

Daves v. Dallas County, an Ex Parte Young case in which the panel held: “With one exception, we agree with the district court that the Plaintiffs have standing. This suit was properly allowed to proceed against most of the judges and the County. As for the Criminal District Court Judges, though, we hold that they are not proper defendants because the Plaintiffs lack standing as to them and cannot overcome sovereign immunity. We also disagree with the district court and hold that the Sheriff can be enjoined to prevent that official’s enforcement of measures violative of federal law.”

Daves v. Dallas County, an Ex Parte Young case in which the panel held: “With one exception, we agree with the district court that the Plaintiffs have standing. This suit was properly allowed to proceed against most of the judges and the County. As for the Criminal District Court Judges, though, we hold that they are not proper defendants because the Plaintiffs lack standing as to them and cannot overcome sovereign immunity. We also disagree with the district court and hold that the Sheriff can be enjoined to prevent that official’s enforcement of measures violative of federal law.”

Hewitt v. Helix Energy Solutions Group, a 2-1 decision involving “a legal question common to all executive, administrative, and professional employees—and to the modestly and highly compensated alike: whether a worker is paid ‘on a salary basis’ under” the Fair Labor Standards Act.

My colleague Michael Hurst wrote an insightful op-ed in the Dallas Morning News about a proposed system of specialized business courts for Texas. He questions whether it fits well with constitutional guaranties of the right to jury trial.

My colleague Michael Hurst wrote an insightful op-ed in the Dallas Morning News about a proposed system of specialized business courts for Texas. He questions whether it fits well with constitutional guaranties of the right to jury trial.

Another voice joined the chorus of appellate observations about perceived excesses involving sealed records in Le v. Exeter Fin. Corp.: “[E]ntrenched litigation practices harden over time, including overbroad sealing practices that shield judicial records from public view for unconvincing (or unarticulated) reasons. Such stipulated sealings are not uncommon. But they are often unjustified. With great respect, we urge litigants and our judicial colleagues to zealously guard the public’s right of access to judicial records their judicial records—so ‘that justice may not be done in a corner.'” No. 20-10377 (March 3, 2021).

Another voice joined the chorus of appellate observations about perceived excesses involving sealed records in Le v. Exeter Fin. Corp.: “[E]ntrenched litigation practices harden over time, including overbroad sealing practices that shield judicial records from public view for unconvincing (or unarticulated) reasons. Such stipulated sealings are not uncommon. But they are often unjustified. With great respect, we urge litigants and our judicial colleagues to zealously guard the public’s right of access to judicial records their judicial records—so ‘that justice may not be done in a corner.'” No. 20-10377 (March 3, 2021).

Just over two years ago, in a single-judge order, Judge Costa rejected a request to seal the oral argument in a Deepwater Horizon claim dispute: “As its right, Claimant ID 100246928 has used the federal courts in its attempt to obtain millions of dollars it believes BP owes because of the oil spill. But it should not able to benefit from this public resource while treating it like a private tribunal when there is no good reason to do so. On Monday, the public will be able to access the courtroom it pays for.” BP Expl. & Prod. v. Claimant ID 100246928, 920 F.3d 209 (5th Cir. 2019). An echo of that order appears in a footnote in a mandamus order from earlier this week–unanimous as to substantive relief but with Judge Costa dissenting on the issue of sealing certain filings: “Judge Costa would not grant the motions to seal the motions and briefing, except for sealing the appendices filed in support of the petition in No. 21-40117, based on his conclusion that the parties have not overcome the right of public access to court filings.” A 2016 National Law Journal article further illustrated his views on these issues.

Just over two years ago, in a single-judge order, Judge Costa rejected a request to seal the oral argument in a Deepwater Horizon claim dispute: “As its right, Claimant ID 100246928 has used the federal courts in its attempt to obtain millions of dollars it believes BP owes because of the oil spill. But it should not able to benefit from this public resource while treating it like a private tribunal when there is no good reason to do so. On Monday, the public will be able to access the courtroom it pays for.” BP Expl. & Prod. v. Claimant ID 100246928, 920 F.3d 209 (5th Cir. 2019). An echo of that order appears in a footnote in a mandamus order from earlier this week–unanimous as to substantive relief but with Judge Costa dissenting on the issue of sealing certain filings: “Judge Costa would not grant the motions to seal the motions and briefing, except for sealing the appendices filed in support of the petition in No. 21-40117, based on his conclusion that the parties have not overcome the right of public access to court filings.” A 2016 National Law Journal article further illustrated his views on these issues.

A trial court in the Northern District of Texas dismissed a case, under Fed. R. Civ. P. 41(b), because a lawyer based in the Eastern District did not retain local counsel as required by the local rules. That rule says that a defendant, or the court, “may move to dismiss the action or any claim against it” “[i]f the plaintiff fails to prosecute or to comply with these rules or a court order.” In Campbell v. Wilkinson, the Fifth Circuit concluded: “This case does not involve a violation of either ‘these rules’—that is, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure—or ‘a court order.’ It involves the violation of a local rule. But Rule 41(b) does not mention local rules. This absence of any express reference to ‘local rules’ in Rule 41(b) thus raises the question whether it is ever appropriate to invoke Rule 41(b) based on nothing more than the violation of a local rule.” The Court concluded that it was not, and reversed because the record did not establish a failure to prosecute. No. 20-1102 (Feb. 19, 2021).

A trial court in the Northern District of Texas dismissed a case, under Fed. R. Civ. P. 41(b), because a lawyer based in the Eastern District did not retain local counsel as required by the local rules. That rule says that a defendant, or the court, “may move to dismiss the action or any claim against it” “[i]f the plaintiff fails to prosecute or to comply with these rules or a court order.” In Campbell v. Wilkinson, the Fifth Circuit concluded: “This case does not involve a violation of either ‘these rules’—that is, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure—or ‘a court order.’ It involves the violation of a local rule. But Rule 41(b) does not mention local rules. This absence of any express reference to ‘local rules’ in Rule 41(b) thus raises the question whether it is ever appropriate to invoke Rule 41(b) based on nothing more than the violation of a local rule.” The Court concluded that it was not, and reversed because the record did not establish a failure to prosecute. No. 20-1102 (Feb. 19, 2021).

Yes, it’s kind of a pain, but it’s your vote, your voice, and your chance to be heard as to a widely-circulated attorney directory. The link to the Super Lawyers nomination site is here, and the deadline to make your nominations is December 21, 2020.

Yes, it’s kind of a pain, but it’s your vote, your voice, and your chance to be heard as to a widely-circulated attorney directory. The link to the Super Lawyers nomination site is here, and the deadline to make your nominations is December 21, 2020.

Automation Support, Inc. v. Philippi, No. 20-10386 (Dec. 8, 2020).

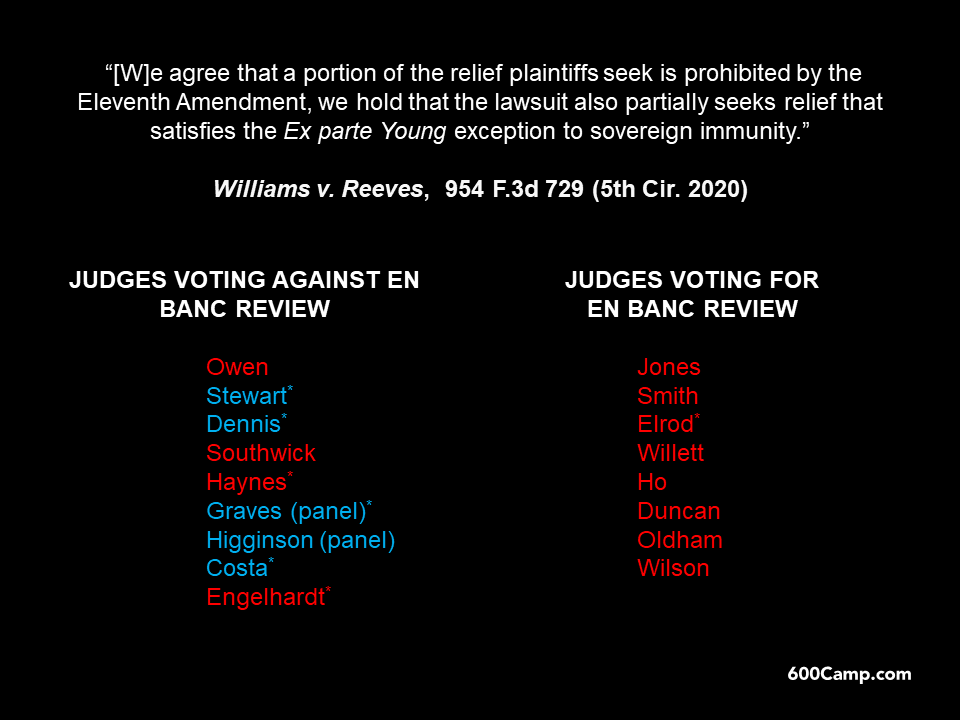

In Williams v. Reeves, 953 F.3d 729 (5th Cir. 2020), “[t]he plaintiffs in this lawsuit are low-income African-American women whose children attend public schools in Mississippi. They filed suit against multiple state officials in 2017, alleging that the current version of the Mississippi Constitution violates the ‘school rights and privileges’ condition of the [1870] Mississippi Readmission Act.” A Fifth Circuit panel found that ” a portion of the relief plaintiffs seek is prohibited by the Eleventh Amendment,” but that “the lawsuit also partially seeks relief that satisfies the Ex parte Young exception to sovereign immunity.” The full court recently denied en banc review by an 8-9 vote; the votes are described below, and they are identical to the split in another recent vote. (Red and blue show the political party of the nominating President, and an * indicates former service as a trial judge.)

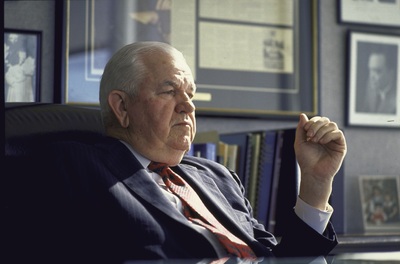

Hon. Thomas Reavley has passed away in Houston, at the age of 99. The Houston Chronicle summarizes his life of extraordinary service to the Texas courts and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, as does the Texas Lawbook. His wisdom and statesmanlike presence will be missed by all.

Hon. Thomas Reavley has passed away in Houston, at the age of 99. The Houston Chronicle summarizes his life of extraordinary service to the Texas courts and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, as does the Texas Lawbook. His wisdom and statesmanlike presence will be missed by all.

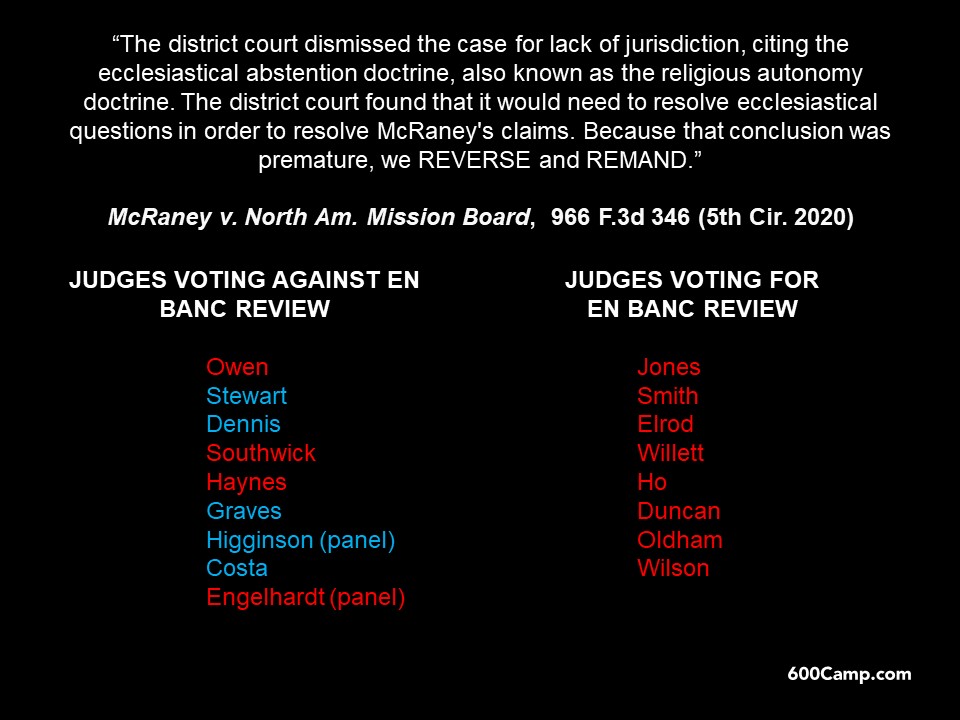

By an 8-9 vote, the Fifth Circuit abstained from en banc review of McRaney v. North American Mission Board, 966 F.3d 346 (5th Cir. 2020), in which the panel found that the application of the ecclesiastical abstention doctrine was premature given the stage of the parties’ case. A breakdown of the votes is below (the third panel member, Judge Clement, has taken senior status and did not participate in the vote):

“Hard cases make bad law,” says the old adage; whether that holds true for Taylor v. Riojas, will remain to be seen. The Supreme Court reversed a qualified-immunity ruling in a case involving what it saw as “shockingly unsanitary” prison cells, finding that the “extreme circumstances” of the case eliminated any dispute about whether the relevant law was clearly-established. No. 19-1261 (U.S. Nov. 2, 2020) (reversing Taylor v. Stevens, 946 F.3d 211 (5th Cir. 2019).

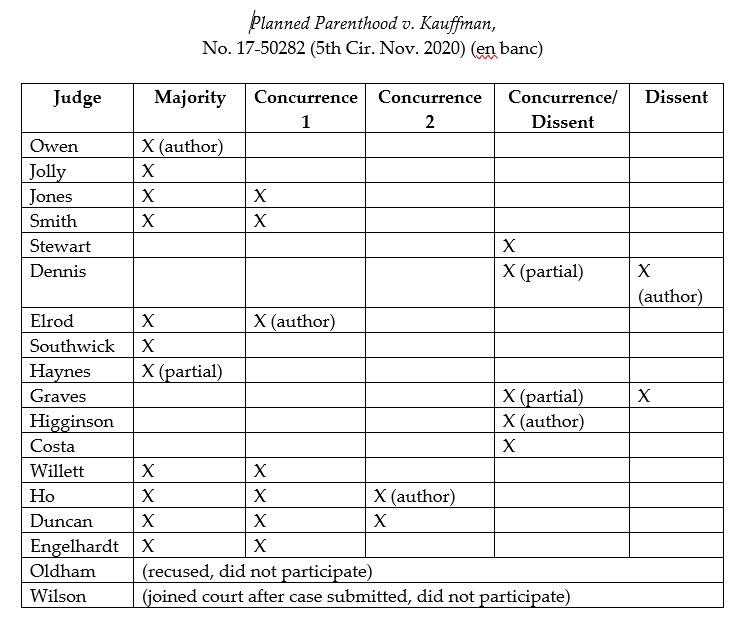

The dry-sounding issue before the en banc court in Planned Parenthood v. Kauffman, No. 17-50282 (Nov. 23, 2020), was “whether 42 U.S.C. § 1396a(a)(23) gives Medicaid patients a right to challenge, under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, a State’s determination that a health care provider is not ‘qualified’ within the meaning of § 1396a(a)(23).” The practical consequence of that issue, however, is significant–who may sue about Texas’s termination of several Planned Parenthood facilities from that state’s Medicaid program.

The majority held that under a 1980 Supreme Court case and the structure of the statute, the patients did not have the right to sue. In so doing, the Fifth Circuit joined the Eighth Circuit and split with five others. A 7-judge concurrence (2 votes shy of a majority, given the configuration of the en banc court for this case) would have reached the merits and rejected them. The opinions are illustrated in the chart below:

The Fifth Circuit recently decided to take three matters en banc:

The Fifth Circuit recently decided to take three matters en banc:

- Cochran v. SEC, 969 F.3d 507 (2020): “Judicial review of Securities and Exchange Commission proceedings lies in the courts of appeals after the agency rules. 15 U.S.C. § 78y. This appeal asks whether a party may nonetheless raise a constitutional challenge to an SEC enforcement action in federal district court before the agency proceeding ends.”

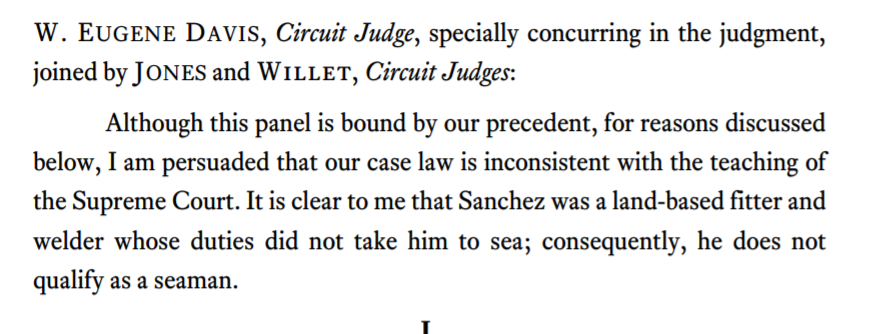

- Sanchez v. Smart Fabricators, 970 F.3d 550 (2020), in which all three panel members urged the en banc court to address Circuit precedent about the definition of a seaman; and

- Whole Woman’s Health v. Paxton, No. 17-51060 (Oct. 13, 2020), an abortion case in which the panel disagreed about the effect of June Medical Services LLC v. Russo, 140 S. Ct. 2103 (2020).

Who knew? The federal bench in Houston just released an inspiring rendition of “We’ll Be Back” from Hamilton, revised to reflect life in the COVID-19 pandemic. Bravo!

Who knew? The federal bench in Houston just released an inspiring rendition of “We’ll Be Back” from Hamilton, revised to reflect life in the COVID-19 pandemic. Bravo!

As society, and the civil justice system, plan a return to more normal operations as the pandemic recedes, Judges Patrick Higginbotham and Lee Rosenthal, and Professor Steven Gensler, have written a perusasive article in Judicature about the importance of 12-person juries in civil cases: “Over the last 40-plus years, the 12- person civil jury has gone from being a fixture in the federal courts to a relative rarity. We should all be concerned. That the Supreme Court has allowed us to use smaller juries does not require us to use them. We can use 12-person juries. The benefits are large; the disadvantages marginal. We’re not suggesting this as a rule or a requirement. We are simply suggesting that judges not reflexively pick six, or eight, or even ten, and instead remember their authority to seat 12. And the great benefits of doing so.”

As society, and the civil justice system, plan a return to more normal operations as the pandemic recedes, Judges Patrick Higginbotham and Lee Rosenthal, and Professor Steven Gensler, have written a perusasive article in Judicature about the importance of 12-person juries in civil cases: “Over the last 40-plus years, the 12- person civil jury has gone from being a fixture in the federal courts to a relative rarity. We should all be concerned. That the Supreme Court has allowed us to use smaller juries does not require us to use them. We can use 12-person juries. The benefits are large; the disadvantages marginal. We’re not suggesting this as a rule or a requirement. We are simply suggesting that judges not reflexively pick six, or eight, or even ten, and instead remember their authority to seat 12. And the great benefits of doing so.”

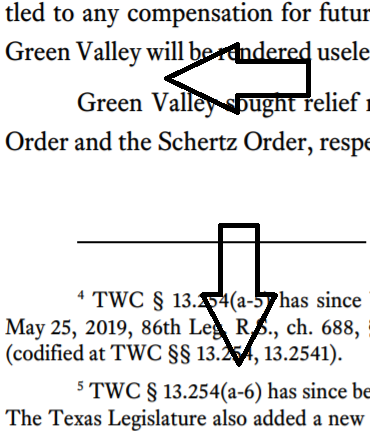

The London Underground reminds its riders to “Mind the Gap” so they do not trip when entering or exiting a train. The Fifth Circuit’s new typography places a notable gap between paragraphs and footnotes. While this sort of line-spacing does not have a technical label like “kerning,” it is nevertheless an important part of the overall look and feel of a piece of legal writing. What are your thoughts on inter-paragraph line spacing?

The London Underground reminds its riders to “Mind the Gap” so they do not trip when entering or exiting a train. The Fifth Circuit’s new typography places a notable gap between paragraphs and footnotes. While this sort of line-spacing does not have a technical label like “kerning,” it is nevertheless an important part of the overall look and feel of a piece of legal writing. What are your thoughts on inter-paragraph line spacing?

Sanchez v. Smart Fabricators, No. 19-20506 (Aug. 14, 2020), held that Sanchez was a Jones Act seaman. All three judges specially concurred in the result, observing:

A notable feature of the Fifth Circuit’s new typography is the amount of kerning (spacing between of letters) in certain elements of an opinion’s first page. (And for those who are

A notable feature of the Fifth Circuit’s new typography is the amount of kerning (spacing between of letters) in certain elements of an opinion’s first page. (And for those who are  weary of the “cases in footnotes,” “1-space, 2-space,” or “anything but Times New Roman” topics, kerning offers an entirely new topic of discussion.) What are your thoughts on appellate kerning?

weary of the “cases in footnotes,” “1-space, 2-space,” or “anything but Times New Roman” topics, kerning offers an entirely new topic of discussion.) What are your thoughts on appellate kerning?

My newest Coale Mind podcast episode looks forward to this fall, when the Supreme Court will consider two decisions by the en banc (full) U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, the federal appellate court for Texas.

My newest Coale Mind podcast episode looks forward to this fall, when the Supreme Court will consider two decisions by the en banc (full) U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, the federal appellate court for Texas.

In the first, California v. Texas, a Fifth Circuit panel found that the individual mandate of the Affordable Care Act was unconstitutional after the repeal of the relevant tax, and the en banc court denied review in a close vote. In the second, Collins v. Mnuchin, the en banc Fifth Circuit found that Fannie Mae’s regulator was structured unconstitutionally.

These cases, important in their own right, also reflect a fascinating encounter between two “conservative” federal courts. Will the Fifth Circuit, widely seen as a particularly conservative court after President Trump’s many appointments, be seen by the Roberts Court as having gone too far? Or will the two courts by “in synch” with each other on these important constitutional issues?

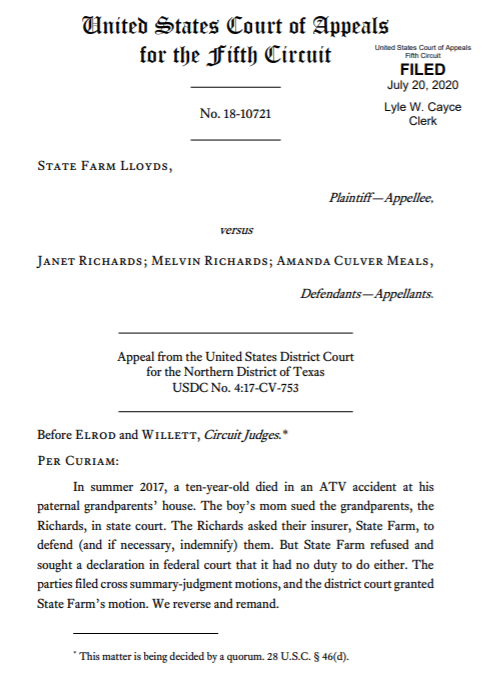

For insurance-coverage lawyers, State Farm Lloyds v. Richards represents another case in which the Fifth Circuit concludes that “the eight-corners rule applies here; the ‘very narrow exception’ does not,” and then finds that the relevant pleading “contains

For insurance-coverage lawyers, State Farm Lloyds v. Richards represents another case in which the Fifth Circuit concludes that “the eight-corners rule applies here; the ‘very narrow exception’ does not,” and then finds that the relevant pleading “contains

allegations within its four corners that potentially constitute a claim within the four corners of the policy.” No. 18-10721 (July 19, 2020).

For fans of legal typography, State Farm Lloyds represents a daring new look – stylish, yet readable!

For fans of legal typography, State Farm Lloyds represents a daring new look – stylish, yet readable!

Wilson, a trustee of Houston’s community-college system, alleged that his censure by the board was done in retaliation for his exercise of First Amendment rights. A panel found that he had stated a claim that was sufficient to survive a Rule 12 challenge:

Wilson, a trustee of Houston’s community-college system, alleged that his censure by the board was done in retaliation for his exercise of First Amendment rights. A panel found that he had stated a claim that was sufficient to survive a Rule 12 challenge:

The above [Circuit] precedent establishes that a reprimand against an elected official for speech addressing a matter of public concern is an actionable First Amendment claim under § 1983. Here, the Board’s censure of Wilson specifically noted it was punishing him for “criticizing other Board members for taking positions that differ from his own” concerning the Qatar campus, including robocalls, local press interviews, and a website. The censure also punished Wilson for filing suit alleging the Board was violating its bylaws. As we have previously held, “[R]eporting municipal corruption undoubtedly constitutes speech on a matter of public concern.” Therefore, we hold that Wilson has stated a claim against HCC under § 1983 in alleging that its Board violated his First Amendment right to free speech when it publicly censured him.

Wilson v. Houston Community College System, 955 F.3d 490 (5th Cir. 2020) (footnote omitted). A vote to take the case en banc produced an 8-8 tie, with these votes (Senior Judge Eugene Davis, who wrote the panel opinion, was not part of the en banc vote):

Congratulations to Judge Cory Wilson of Mississippi, who was confirmed by the Senate yesterday as the newest member of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

Congratulations to Judge Cory Wilson of Mississippi, who was confirmed by the Senate yesterday as the newest member of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

A recent article in the Baylor Law Review by Kylie Calabrese, a student of the able Rory Ryan at the Baylor Law School, provides a thorough and well-documented analysis of In re: JP Morgan Chase & Co., 915 F.3d 494 (5th Cir. 2019) and its implications for mandamus practice in the Fifth Circuit.

A recent article in the Baylor Law Review by Kylie Calabrese, a student of the able Rory Ryan at the Baylor Law School, provides a thorough and well-documented analysis of In re: JP Morgan Chase & Co., 915 F.3d 494 (5th Cir. 2019) and its implications for mandamus practice in the Fifth Circuit.

Here is the PowerPoint for my June 2 presentation to the DBA’s Appellate Law Section about Fifth Court commercial-litigation opinions over the last twelve months.

Here is the PowerPoint for my June 2 presentation to the DBA’s Appellate Law Section about Fifth Court commercial-litigation opinions over the last twelve months.

Recent orders about conducting trials during the pandemic highlight the different procedural structures of the state and federal courts.

Recent orders about conducting trials during the pandemic highlight the different procedural structures of the state and federal courts.

In the state system, the Texas Supreme Court recently released its seventeenth emergency order about when and how jury trials may resume. (An order, incidentally, that I got from the txcourts.gov website, which shows progress in returning that site to normal after the recent hacker attack.)

In the federal system, the recent order in In re Tanner reminds of the considerable district court discretion about such matters: “[T]he district court has given great consideration to the COVID-19 issues addressed by Tanner. . . . [W]hatever each of us as judges might have done in the same circumstance is not the question. Instead, as cited below, the standards are much higher for evaluating the district court’s decision” for purposes of a writ of mandamus or prohibition. No. 20-10510 (May 29, 2020).

I spoke today, virtually, to the Texas Bar CLE’s 33rd “Advanced Evidence and Discovery Course,” which would have been in San Antonio. My topic was proving up damages in a commercial case, and I focused on ten specific issues identified in recent Texas and Fifth Circuit cases. I also showed off some smooth hand gestures, as you can see above. Here is a copy of my PowerPoint. The Bar staff did a terrific job with the A/V logistics and I look forward to doing another program with them soon.

I spoke today, virtually, to the Texas Bar CLE’s 33rd “Advanced Evidence and Discovery Course,” which would have been in San Antonio. My topic was proving up damages in a commercial case, and I focused on ten specific issues identified in recent Texas and Fifth Circuit cases. I also showed off some smooth hand gestures, as you can see above. Here is a copy of my PowerPoint. The Bar staff did a terrific job with the A/V logistics and I look forward to doing another program with them soon.

The “finality trap” can arise when a plaintiff sues two defendants and then (a) voluntarily dismisses one defendant without prejudice, and then (b) litigates to conclusion against the other and loses. The plaintiff’s ability to appeal the outcome of proceeding (b) is affected by the lack of a final judgment in proceeding (a), because under Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(b), there is not a final decision as to any one defendant until there is a final decision for all defendants

The “finality trap” can arise when a plaintiff sues two defendants and then (a) voluntarily dismisses one defendant without prejudice, and then (b) litigates to conclusion against the other and loses. The plaintiff’s ability to appeal the outcome of proceeding (b) is affected by the lack of a final judgment in proceeding (a), because under Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(b), there is not a final decision as to any one defendant until there is a final decision for all defendants

Williams v. Seidenbach found that entry of a partial final judgment under Rule 54(b) solved the plaintiffs’ problem in that case. (Judge Ho, joined by Chief Judge Owen and Judges Jones, Stewart, Dennis, Elrod, Haynes, Graves, Higginson, and Engelhardt).

A concurrence suggested that future litigants consider “bindingly disclaiming their right to reassert any dismissed-without-prejudice claims” as way to solve the problem. (Judge Willett, joined by Judge Southwick) (Note that all opinions appear in the same PDF document, linked above).

A concurrence suggested that future litigants consider “bindingly disclaiming their right to reassert any dismissed-without-prejudice claims” as way to solve the problem. (Judge Willett, joined by Judge Southwick) (Note that all opinions appear in the same PDF document, linked above).

A dissent, focused on the text of Rules 41 and 54, observed that once a “Rule 41(a) dismissal ‘adjudicated’ the plaintiffs’ claims . . . there were no claims pending after that adjudication” which mean that “Rule 54(b) was (and still is) completely irrelevant.” (Judge Oldham, joined by Judges Smith, Duncan and – unexpectedly – Costa).

To be continued . . .

After recently addressing a party’s rights to oral argument in a dispute about enforcement of an arbitration award, the Fifth Circuit then returned to Sun Coast Resources v. Conrad to review the prevailing party’s motion for sanctions under Fed. R. App. 38 for a frivolous appeal.The Court observed:

After recently addressing a party’s rights to oral argument in a dispute about enforcement of an arbitration award, the Fifth Circuit then returned to Sun Coast Resources v. Conrad to review the prevailing party’s motion for sanctions under Fed. R. App. 38 for a frivolous appeal.The Court observed:

“[T]he case for Rule 38 sanctions is strongest in matters involving malice, not incompetence. And our decision on Sun Coast’s appeal was careful not to assume the former. As to the merits of its appeal—including the company’s

failure to disclose that it cited Opalinski II rather than Opalinski I to the arbitrator—we observed that ‘[t]he best that may be said for Sun Coast is that it badly misreads the record.’ As to its demand for oral argument, we stated that ‘Sun Coast’s motion misunderstands the federal appellate process in more ways than one.’

Perhaps Sun Coast earnestly (if mistakenly) believed it had a valid legal claim to press. Or perhaps it was bad faith—maximizing legal expense to drive a less-resourced adversary to drop the case or settle for less. Or perhaps its decisions were driven by counsel. But we must resolve the pending motion based on facts and evidence—not speculation. We sympathize with Conrad . . . [b]ut we conclude that this is a time for grace, not punishment.”

No. 19-20058 (May 7, 2020) (citations omitted).

While the timing is coincidental, the case is an instructive companion to the Texas Supreme Court’s recent opinion in Brewer v. Lennox Hearth Products LLC, which reversed a sanctions award. That Court noted that “while the absence of authoritative guidance is not a license to act with impunity, bad faith is required to impose sanctions under the court’s inherent authority,” and this held that “the sanctions order in this case cannot stand because evidence of bad faith is lacking.” No. 18-0426 (Tex. April 24, 2020) (footnotes omitted).

Related to the Fifth Circuit’s recent general reminder in Sun Coast Resources v. Conrad about when oral argument will occur, Chief Judge Owens’s April 20 Covid-19 order makes clear that individual panels may decide when to use “Zoom” or other such conferencing technology. H/T to Louisiana’s Ray Ward for drawing my attention to this order.

Related to the Fifth Circuit’s recent general reminder in Sun Coast Resources v. Conrad about when oral argument will occur, Chief Judge Owens’s April 20 Covid-19 order makes clear that individual panels may decide when to use “Zoom” or other such conferencing technology. H/T to Louisiana’s Ray Ward for drawing my attention to this order.

Sun Coast Resources Inc. v. Conrad, No. 19-20058 (April 16, 2020), involved a challenge to an arbitration award. The challenging party did not agree with the Fifth Circuit’s decision to proceed without oral argument, and filed a motion seeking an oral argument. It was denied and the Court’s explanation is instructive:

Sun Coast Resources Inc. v. Conrad, No. 19-20058 (April 16, 2020), involved a challenge to an arbitration award. The challenging party did not agree with the Fifth Circuit’s decision to proceed without oral argument, and filed a motion seeking an oral argument. It was denied and the Court’s explanation is instructive:

- “Sun Coast’s motion misunderstands the federal appellate process in

more ways than one. To begin, the motion claims that ‘oral argument is the

norm rather than the exception.’ Not true. ‘More than 80 percent of federal

appeals are decided solely on the basis of written briefs. Less than a quarter

of all appeals are decided following oral argument.'”; - “Sun Coast suggests that deciding this case without oral argument would be ‘akin to . . . cafeteria justice.’ The Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure state otherwise. They authorize “a panel of three judges who have examined the briefs and record” to ‘unanimously agree[] that oral argument is unnecessary for any of the following reasons”—such as the fact that “the dispositive issue or issues have been authoritatively decided,” or that “the facts and legal arguments are adequately presented in the briefs and record, and the decisional process would not be significantly aided by oral argument.””; and

- “[A]nother tactic powerful economic interests sometimes use against

the less resourced is to increase litigation costs in an attempt to bully the

opposing party into submission by war of attrition—for example, by filing a

meritless appeal of an arbitration award won by the economically weaker

party, and then maximizing the expense of litigating that appeal. Dispensing with oral argument where the panel unanimously agrees it is unnecessary, and where the case for affirmance is so clear, is not cafeteria justice—it is simply justice.” (citations omitted and emphasis added in all the above quotes).

The fast-paced litigation about access to abortion during the COVID-19 pandemic produced a strong statement about government power (including the power of the administrative state) during a health crisis: “The bottom line is this: when faced with a society-threatening epidemic, a state may implement emergency measures that curtail constitutional rights so long as the measures have at least some ‘real or substantial relation’ to the public health crisis and are not ‘beyond all question, a plain, palpable invasion of rights secured by the fundamental law.'” In re Abbott, No. 20-50264 (April 7, 2020) (orig. proceeding) (quoting Jacobson v. Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11 (1905)). The opinion has gathered national coverage from diverse media outlets such as CNN and Reason.

The fast-paced litigation about access to abortion during the COVID-19 pandemic produced a strong statement about government power (including the power of the administrative state) during a health crisis: “The bottom line is this: when faced with a society-threatening epidemic, a state may implement emergency measures that curtail constitutional rights so long as the measures have at least some ‘real or substantial relation’ to the public health crisis and are not ‘beyond all question, a plain, palpable invasion of rights secured by the fundamental law.'” In re Abbott, No. 20-50264 (April 7, 2020) (orig. proceeding) (quoting Jacobson v. Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11 (1905)). The opinion has gathered national coverage from diverse media outlets such as CNN and Reason.

Surprising no one, the constitutional challenge to the CFPB’s structure presented by CFPB v. All American Check Cashing will be reviewed en banc by the full Fifth Circuit.

Surprising no one, the constitutional challenge to the CFPB’s structure presented by CFPB v. All American Check Cashing will be reviewed en banc by the full Fifth Circuit.

Faced with “extraordinarily confused” case law within the Circuit about the federal-officer removal statute (28 USC sec. 1442(a)(1)), the en banc Court’s opinion in Latiolais v. Huntington Ingalls is intended to “strip away the confusion, align with sister circuits, and rely on the plain language of the statute, as broadened in 2011.” The new test requires a defendant to show: “(1) it has asserted a colorable federal defense, (2) it is a ‘person’ within the meaning of the statute, (3) that has acted pursuant to a federal officer’s directions, and (4) the charged conduct is connected or associated with an act pursuant to a federal officer’s directions.” It abandons a previously-recognized “causal nexus” requirement. Accordingly, the defendant shipbuilder “was entitled to remove this negligence case filed by a former Navy machinist because of his exposure to asbestos while the Navy’s ship was being repaired at the Avondale shipyard under a federal contract.” No. 18-30652 (Feb. 24, 2020). (Above, the formidable bow of the U.S.S. Somerset, the last ship launched from the long-serving shipyard.)

Faced with “extraordinarily confused” case law within the Circuit about the federal-officer removal statute (28 USC sec. 1442(a)(1)), the en banc Court’s opinion in Latiolais v. Huntington Ingalls is intended to “strip away the confusion, align with sister circuits, and rely on the plain language of the statute, as broadened in 2011.” The new test requires a defendant to show: “(1) it has asserted a colorable federal defense, (2) it is a ‘person’ within the meaning of the statute, (3) that has acted pursuant to a federal officer’s directions, and (4) the charged conduct is connected or associated with an act pursuant to a federal officer’s directions.” It abandons a previously-recognized “causal nexus” requirement. Accordingly, the defendant shipbuilder “was entitled to remove this negligence case filed by a former Navy machinist because of his exposure to asbestos while the Navy’s ship was being repaired at the Avondale shipyard under a federal contract.” No. 18-30652 (Feb. 24, 2020). (Above, the formidable bow of the U.S.S. Somerset, the last ship launched from the long-serving shipyard.)

I spoke at the State Bar’s “Litigation Update” last Friday to give a Supreme Court and Fifth Circuit update; here is my PowerPoint from that presentation. It covers SCOTUS and CTA5 cases of general interest to business litigators since the last Litigation Update seminar in January 2019.

I spoke at the State Bar’s “Litigation Update” last Friday to give a Supreme Court and Fifth Circuit update; here is my PowerPoint from that presentation. It covers SCOTUS and CTA5 cases of general interest to business litigators since the last Litigation Update seminar in January 2019.