If you think that the modern administrative state relies heavily upon acronyms, you are not alone, as the Fifth Circuit illustrated in Leigh Ann H v. Reisel ISD, No. 20-50003-CV (Nov. 22, 2021):

Category Archives: Administrative Law

In a rough stretch for the administrative state, after the Fifth Circuit’s recent skeptical rejection of an FDA regulation of e-cigarettes, another panel stayed OSHA’s vaccine-mandate regulation. It based its decision on several administrative-law principles and summarized:

In a rough stretch for the administrative state, after the Fifth Circuit’s recent skeptical rejection of an FDA regulation of e-cigarettes, another panel stayed OSHA’s vaccine-mandate regulation. It based its decision on several administrative-law principles and summarized:

“[T]he Mandate’s strained prescriptions combine to make it the rare government pronouncement that is both overinclusive (applying to employers and employees in virtually all industries and workplaces in America, with little attempt to account for the obvious differences between the risks facing, say, a security guard on a lonely night shift, and a meatpacker working shoulder to shoulder in a cramped warehouse) and underinclusive (purporting to save employees with 99 or more coworkers from a “grave danger” in the workplace, while making no attempt to shield employees with 98 or fewer coworkers from the very same threat). The Mandate’s stated impetus—a purported “emergency” that the entire globe has now endured for nearly two years, and which OSHA itself spent nearly two months responding to—is unavailing as well. And its promulgation grossly exceeds OSHA’s statutory authority.”

No. 21-60845 (Nov. 12, 2021) (footnotes omitted, emphasis in original).

In Wages & White Lions Investments LLC v. FDA, the Fifth Circuit found many problems with the FDA’s denial of a company’s application to market flavored e-cigarettes. Among them, the Court identified two issues with the FDA’s review of the company’s marketing plan to avoid improper product use by young people; the Court’s reasoning is of broad general interest for Daubert practice as well as administrative law:

In Wages & White Lions Investments LLC v. FDA, the Fifth Circuit found many problems with the FDA’s denial of a company’s application to market flavored e-cigarettes. Among them, the Court identified two issues with the FDA’s review of the company’s marketing plan to avoid improper product use by young people; the Court’s reasoning is of broad general interest for Daubert practice as well as administrative law:

- The FDA’s contention “that no marketing plan would be sufficient, so it stopped working”: “That’s like an Article III judge saying that she stopped reading briefs because she previously found them unhelpful.”

- Reliance on expertise and experience. “An agency’s ‘experience and expertise’ presumably enable the agency to provide the required explanation, but they do not substitute for the explanation, any more than an expert witness’s credentials substitute for the substantive requirements applicable to the expert’s testimony under [Rule] 702.”

No. 21-60766 (Oct. 26, 2021).

A key issue facing OSHA’s new COVID regulation is whether a “grave danger” justified the agency acting so rapidly. In an unusual flash of appellate-court wit, the Fifth Circuit temporarily stayed the regulation, observing:

(Regrettably, Judge Graves was not on the panel.)

A frequent international traveler alleged that he had been placed on a TSA list that required additional, invasive searches of him when he flew. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of the several Constitutional claims that he raised in a lawsuit against the leaders of the relevant federal agencies:

A frequent international traveler alleged that he had been placed on a TSA list that required additional, invasive searches of him when he flew. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of the several Constitutional claims that he raised in a lawsuit against the leaders of the relevant federal agencies:

“In short, Ghedi has no right to hassle-free travel. In the Supreme Court’s view, international travel is a ‘freedom’ subject to ‘reasonable governmental regulation.’ And when it comes to reasonable governmental regulation, our sister circuits have held that Government-caused inconveniences during international travel do not deprive a traveler’s right to travel. In the Sixth Circuit’s view, ‘incidental or negligible’ delays of ‘ten minutes’ to ‘an entire day’ do not ‘implicate the right to travel.’ The Second and Tenth Circuits have held the same. Ghedi has therefore failed to plausibly allege that he has been deprived of his right to travel internationally by the extra security measures he has experienced.”

Ghedi v. Mayorkas, No. 20-10995 (Oct. 25, 2021) (footnotes omitted).

Johnson alleged that BOKF’s collection of “extended overdraft charges” (fees charged to customers who overdraw on their checking accounts and fail to timely pay the bank for covering the overdraft) were “interest” within the meaning of the National Bank Act. The Fifth Circuit rejected her claim, giving Auer deference to an interpretive letter of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and noting as to the relevant considerations:

Johnson alleged that BOKF’s collection of “extended overdraft charges” (fees charged to customers who overdraw on their checking accounts and fail to timely pay the bank for covering the overdraft) were “interest” within the meaning of the National Bank Act. The Fifth Circuit rejected her claim, giving Auer deference to an interpretive letter of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and noting as to the relevant considerations:

- Authoritative. The letter was drafted by the OCC’s chief counsel, in response to a bank’s request for OCC guidance, and thus “bears the hallmarks of an official interpretation by OCC.”

- Within the agency’s substantive expertise. OCC administers the National Bank Act, the letter “appears aimed at providing assurance to regulated parties,” and did not appear to merely take a “convenient litigating position.”

- Fair and considered judgment. The letter “is neither plainly erroneous nor inconsistent with the regulations it interprets.”

No. 18-11375 (Sept. 29, 2021).

Huawei Technologies USA v. FCC presents an exhaustive summary of modern-day administrative law, in the context of reviewing an FCC rule that excluded Huawei from federal funds as a security risk. As the Court summarized its several holdings:

Huawei Technologies USA v. FCC presents an exhaustive summary of modern-day administrative law, in the context of reviewing an FCC rule that excluded Huawei from federal funds as a security risk. As the Court summarized its several holdings:

Their most troubling challenge is that the rule illegally arrogates to the FCC the power to make judgments about national security that lie outside the agency’s authority and expertise. That claim gives us pause. The FCC deals with national communications, not foreign relations. It is not the Department of Defense, or the National Security Agency, or the President. If we were convinced that the FCC is here acting as “a sort of junior varsity [State Department],” Mistretta v. United States, 488 U.S. 361, 427 (1989) (Scalia, J., dissenting), we would set the rule aside.

But no such skullduggery is afoot. Assessing security risks to telecom networks falls in the FCC’s wheelhouse. And the agency’s judgments about national security receive robust input from other expert agencies and officials. We are therefore persuaded that, in crafting the rule, the agency reasonably acted within the broad authority Congress gave it to regulate communications.

No. 19-60896 (June 18, 2021).

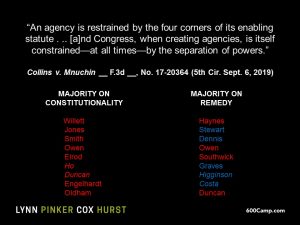

The full Fifth Circuit declined to grant en banc review to State of Texas v. Rettig, 987 F.3d 518 (5th Cir. 2021), which involved constitutional challenges by certain states to two aspects of the Affordable Care Act. They contended that the “Certification Rule” violated the nondelegation doctrine, and that section 9010 of the ACA violated the Spending Clause and the Tenth Amendment’s doctrine of intergovernmental tax immunity. The panel found the laws constitutional, in an opinion by Judge Haynes that was joined by Judges Barksdale and Willett. “In the en banc poll, five judges voted in favor of rehearing (Judges Jones, Smith, Elrod, Ho, and Duncan), and eleven judges voted against rehearing (Chief Judge Owen, and Judges Stewart, Dennis, Southwick, Haynes, Graves, Higginson, Costa, Willett, Engelhardt, and Wilson),” with Judge Oldham not participating, and the five pro-rehearing judges joining a dissent.

The full Fifth Circuit declined to grant en banc review to State of Texas v. Rettig, 987 F.3d 518 (5th Cir. 2021), which involved constitutional challenges by certain states to two aspects of the Affordable Care Act. They contended that the “Certification Rule” violated the nondelegation doctrine, and that section 9010 of the ACA violated the Spending Clause and the Tenth Amendment’s doctrine of intergovernmental tax immunity. The panel found the laws constitutional, in an opinion by Judge Haynes that was joined by Judges Barksdale and Willett. “In the en banc poll, five judges voted in favor of rehearing (Judges Jones, Smith, Elrod, Ho, and Duncan), and eleven judges voted against rehearing (Chief Judge Owen, and Judges Stewart, Dennis, Southwick, Haynes, Graves, Higginson, Costa, Willett, Engelhardt, and Wilson),” with Judge Oldham not participating, and the five pro-rehearing judges joining a dissent.

Several years ago, mathematicians rejoiced at the mapping of the world’s most complex structure, the 248-dimension “Lie Group E8” (right). Not to be outdone, the en banc Fifth Circuit has issued Brackeen v. Haaland, a 325-page set of opinions about the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act–a work so complicated that a six-page per curiam introduction is needed to explain the Court’s divisions on the issues. No. 18-11479 (April 6, 2021). The splits, opinions, and holdings will be reviewed in future posts.

Several years ago, mathematicians rejoiced at the mapping of the world’s most complex structure, the 248-dimension “Lie Group E8” (right). Not to be outdone, the en banc Fifth Circuit has issued Brackeen v. Haaland, a 325-page set of opinions about the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act–a work so complicated that a six-page per curiam introduction is needed to explain the Court’s divisions on the issues. No. 18-11479 (April 6, 2021). The splits, opinions, and holdings will be reviewed in future posts.

Belcher complained about the FDIC’s power to take his deposition. The parties, and the panel majority, agreed that his lawsuit did not become moot even after the challenged deposition occurred: ‘Because the district court on remand can ‘fashion some form of meaningful relief,’ appeal is not moot. Exactly what that relief might entail is beyond the scope of our concern. However, it is undisputed by the parties that the district court could strike Belcher’s deposition testimony before the FDIC.” The majority also noted that the district court could address the FDIC’s sharing of the transcript. A dissent observed: “I see no reason to override what common sense suggests: the appeal of an order requiring a deposition is moot once the deposition is over.” FDIC v. Belcher, No. 19-31023 (Oct. 26, 2020).

Belcher complained about the FDIC’s power to take his deposition. The parties, and the panel majority, agreed that his lawsuit did not become moot even after the challenged deposition occurred: ‘Because the district court on remand can ‘fashion some form of meaningful relief,’ appeal is not moot. Exactly what that relief might entail is beyond the scope of our concern. However, it is undisputed by the parties that the district court could strike Belcher’s deposition testimony before the FDIC.” The majority also noted that the district court could address the FDIC’s sharing of the transcript. A dissent observed: “I see no reason to override what common sense suggests: the appeal of an order requiring a deposition is moot once the deposition is over.” FDIC v. Belcher, No. 19-31023 (Oct. 26, 2020).

The most recent episode of the Coale Mind podcast discusses Mi Familia Vota v. Abbott, No. 20-50793 (Oct. 14, 2020), a challenge to several Texas voting laws in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. The case reminds of two important limits on federal judicial power in such disputes:

The most recent episode of the Coale Mind podcast discusses Mi Familia Vota v. Abbott, No. 20-50793 (Oct. 14, 2020), a challenge to several Texas voting laws in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. The case reminds of two important limits on federal judicial power in such disputes:

- Under Ex parte Young (Mr. Young appears to the right): “Although a court can enjoin state officials from enforcing statutes, such an injunction must be directed to those who have the authority to enforce those statutes. In the present case, that would be county or other local officials.”

- And naming the right defendant is only the first hurdle posed by federalism: “An examination of the relief that the Plaintiffs seek in the case before us reveals that in many instances, court-ordered-relief would require the Governor or the Secretary of State to issue an executive order or directive or to take other sweeping affirmative action. If implemented by the district court, many of the directives requested by the Plaintiffs would violate principles of federalism.”

“[C]ourt changes of election laws close in time to the election are strongly disfavored. … [I]n staying a preliminary injunction that would change election laws eighteen days before early voting begins, we recognize the value of preserving the status quo in a voting case on the eve of an election, and we find that the traditional factors for granting a stay favor granting one here.” Texas Alliance for Retired Americans v. Hughs, No. 20-40643 (Sept. 30, 2020).

“[C]ourt changes of election laws close in time to the election are strongly disfavored. … [I]n staying a preliminary injunction that would change election laws eighteen days before early voting begins, we recognize the value of preserving the status quo in a voting case on the eve of an election, and we find that the traditional factors for granting a stay favor granting one here.” Texas Alliance for Retired Americans v. Hughs, No. 20-40643 (Sept. 30, 2020).

A home health care provider, feeling trapped by Medicare’s slow and complex administrative review process, sought relief in court. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the denial of its application for an injunction, observing: “The Constitution entrusts the political branches, not the judiciary, with making difficult and value-laden policy decisions. There were an infinite number of schemes Congress could have reasonably selected. Congress settled on one that guarantees at least two levels of administrative review and judicial review. And in the case of a backlog, Congress provided the ability to bypass long waits on the way to judicial review. Sahara rejected that option. At bottom, Sahara believes a different scheme would be better. But we lack the power to change it.” Sahara Health Care v. Azar, No. 18-41120 (Sept. 18, 2020) (emphasis added).

A home health care provider, feeling trapped by Medicare’s slow and complex administrative review process, sought relief in court. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the denial of its application for an injunction, observing: “The Constitution entrusts the political branches, not the judiciary, with making difficult and value-laden policy decisions. There were an infinite number of schemes Congress could have reasonably selected. Congress settled on one that guarantees at least two levels of administrative review and judicial review. And in the case of a backlog, Congress provided the ability to bypass long waits on the way to judicial review. Sahara rejected that option. At bottom, Sahara believes a different scheme would be better. But we lack the power to change it.” Sahara Health Care v. Azar, No. 18-41120 (Sept. 18, 2020) (emphasis added).

The opinion also provides an original source for the saying, “[t]he best laid plans of mice and men oft go awry” —

“Applying Skidmore, we ask whether EPA’s interpretation of Title V in the Hunter Order is persuasive. Specifically, we inquire into the persuasiveness of EPA’s current view that the Title V permitting process does not require substantive reevaluation of the underlying Title I preconstruction permits applicable to a pollution source. As we read it, the Hunter Order defends the agency’s interpretation based principally on Title V’s text, Title V’s structure and purpose, and the structure of the Act as a whole. Having examined these reasons and found them persuasive, we conclude that EPA’s current approach to Title V merits Skidmore deference.” Environmental Integrity Project v. EPA, No. 18-60384 (Aug. 13, 2020) (emphasis added).

“Applying Skidmore, we ask whether EPA’s interpretation of Title V in the Hunter Order is persuasive. Specifically, we inquire into the persuasiveness of EPA’s current view that the Title V permitting process does not require substantive reevaluation of the underlying Title I preconstruction permits applicable to a pollution source. As we read it, the Hunter Order defends the agency’s interpretation based principally on Title V’s text, Title V’s structure and purpose, and the structure of the Act as a whole. Having examined these reasons and found them persuasive, we conclude that EPA’s current approach to Title V merits Skidmore deference.” Environmental Integrity Project v. EPA, No. 18-60384 (Aug. 13, 2020) (emphasis added).

OSHA regulations have an exemption for “diving performed solely as a necessary part of a scientific, research, or educational activity by employees whose sole purpose for diving is to perform scientific research tasks. Scientific diving does not include performing any tasks usually associated with commercial diving such as: Placing or removing heavy objects underwater; inspection of pipelines and similar objects; construction; demolition; cutting or welding; or the use of explosives.”

OSHA regulations have an exemption for “diving performed solely as a necessary part of a scientific, research, or educational activity by employees whose sole purpose for diving is to perform scientific research tasks. Scientific diving does not include performing any tasks usually associated with commercial diving such as: Placing or removing heavy objects underwater; inspection of pipelines and similar objects; construction; demolition; cutting or welding; or the use of explosives.”

OSHA concluded that the divers who clean the tanks at the Houston Aquarium were not “scientific divers” under this regulation; the Fifth Circuit saw otherwise: “The divers are engaged in a ‘studious … examination’ and ‘detailed study’ when they observe the animals for abnormalities, and when they work to keep the animals in the Aquarium alive, healthy, and breeding. That an organization collaborates among employees and engages in verbal communication does not mean that the examination and study of the animals in the tanks is not ‘studious’ or ‘detailed.’ Nothing about the feeding and cleaning dives renders the information that the trained scientists performing the dives gather during these dives outside of the definition of ‘research.’” Houston Aquarium, Inc. v. OSHRC, No. 19-60245 (July 15, 2020).

A manufacturer of vaping liquid, invoking the structural limitations imposed on administrative agencies by the delegation doctrine, challenged the FDA’s power to regulate it. The Fifth Circuit observed: “The [Supreme] Court might well decide—perhaps soon—to reexamine or revive the nondelegation doctrine. But ‘[w]e are not supposed to . . . read tea leaves to predict where it might end up.'” (citation omitted). That observation was case-dispositive: “The [Supreme] Court has found only two delegations to be unconstitutional. Ever. And none in more than eighty years.” Under that precedent, Congress’s delegation of authority to the FDA in this area showed a “sufficiently intelligible principle,” constrained by Congress’s definition of “tobacco product,” and by Congress having “ma[de] many of the key regulatory decisions itself.” Big Time Vapes, Inc. v. Food & Drug Admin., No. 19-60921 (June 25, 2020).

A manufacturer of vaping liquid, invoking the structural limitations imposed on administrative agencies by the delegation doctrine, challenged the FDA’s power to regulate it. The Fifth Circuit observed: “The [Supreme] Court might well decide—perhaps soon—to reexamine or revive the nondelegation doctrine. But ‘[w]e are not supposed to . . . read tea leaves to predict where it might end up.'” (citation omitted). That observation was case-dispositive: “The [Supreme] Court has found only two delegations to be unconstitutional. Ever. And none in more than eighty years.” Under that precedent, Congress’s delegation of authority to the FDA in this area showed a “sufficiently intelligible principle,” constrained by Congress’s definition of “tobacco product,” and by Congress having “ma[de] many of the key regulatory decisions itself.” Big Time Vapes, Inc. v. Food & Drug Admin., No. 19-60921 (June 25, 2020).

A Texas business alleged that the CARES Act impermissibly discriminated against it as a bankruptcy debtor. The Fifth Circuit, citing its rule of orderliness, noted that it “has concluded that all injunctive relief directed at the [Small Business Administration] is absolutely prohibited.” Accordingly, “the bankruptcy court exceeded its authority when it issued an injunction against the SBA administrator … .” Hidalgo County Emergency Service Foundation v. Carranza, No. 20-40368 (June 22, 2020).

A Texas business alleged that the CARES Act impermissibly discriminated against it as a bankruptcy debtor. The Fifth Circuit, citing its rule of orderliness, noted that it “has concluded that all injunctive relief directed at the [Small Business Administration] is absolutely prohibited.” Accordingly, “the bankruptcy court exceeded its authority when it issued an injunction against the SBA administrator … .” Hidalgo County Emergency Service Foundation v. Carranza, No. 20-40368 (June 22, 2020).

Despite the complexity of a dispute about telecommunication regulations, the parties’ performance mattered: “Sprint and Verizon’s conduct, while certainly not dispositive, is nevertheless informative. Sprint and Verizon are among America’s largest IXCs and are sophisticated market participants. Yet, they waited more than eighteen years to object to the LECs’ access charges for intraMTA wireless-to-wireline calls, paying hundreds of millions of dollars in the process. Moreover, over that same timeframe, Sprint’s and Verizon’s LEC affiliates imposed access charges on IXCs, including on each other, for intraMTA wireless-to-wireline calls. We decline to award Sprint and Verizon, who sat on their hands for the better part of two decades, a nine-figure windfall based on an interpretation of § 251(g) that is divorced from both the 1996 Act’s text and industry practice.” No. 18-10768 (May 27, 2020). (LPCH was one of the counsel for the prevailing side of this case.)

Despite the complexity of a dispute about telecommunication regulations, the parties’ performance mattered: “Sprint and Verizon’s conduct, while certainly not dispositive, is nevertheless informative. Sprint and Verizon are among America’s largest IXCs and are sophisticated market participants. Yet, they waited more than eighteen years to object to the LECs’ access charges for intraMTA wireless-to-wireline calls, paying hundreds of millions of dollars in the process. Moreover, over that same timeframe, Sprint’s and Verizon’s LEC affiliates imposed access charges on IXCs, including on each other, for intraMTA wireless-to-wireline calls. We decline to award Sprint and Verizon, who sat on their hands for the better part of two decades, a nine-figure windfall based on an interpretation of § 251(g) that is divorced from both the 1996 Act’s text and industry practice.” No. 18-10768 (May 27, 2020). (LPCH was one of the counsel for the prevailing side of this case.)

“For a generation, the State of Texas and a federally recognized Indian tribe, the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, have litigated the Pueblo’s attempts to conduct various gaming activities on its reservation near El Paso. This latest case poses familiar questions that yield familiar answers: (1) which federal law governs the legality of the Pueblo’s gaming operations—the Restoration Act (which bars gaming that violates Texas law) or the more permissive Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (which “establish[es] . . . Federal standards for gaming on Indian lands”); and (2) whether the district court correctly enjoined the Pueblo’s gaming operations.” Unfortunately for the tribe, the Fifth Circuit found that a previous opinion conclusively settled these issues in favor of the State of Texas. The opinion also discusses the proper scope of injunctive relief for such a situation. Texas v. Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, No. 19-50400 (April 2, 2020).

“For a generation, the State of Texas and a federally recognized Indian tribe, the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, have litigated the Pueblo’s attempts to conduct various gaming activities on its reservation near El Paso. This latest case poses familiar questions that yield familiar answers: (1) which federal law governs the legality of the Pueblo’s gaming operations—the Restoration Act (which bars gaming that violates Texas law) or the more permissive Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (which “establish[es] . . . Federal standards for gaming on Indian lands”); and (2) whether the district court correctly enjoined the Pueblo’s gaming operations.” Unfortunately for the tribe, the Fifth Circuit found that a previous opinion conclusively settled these issues in favor of the State of Texas. The opinion also discusses the proper scope of injunctive relief for such a situation. Texas v. Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, No. 19-50400 (April 2, 2020).

DISH Network declared an impasse after lengthy negotiations with the Communication Workers of America. The NLRB rejected that declaration; the Fifth Circuit reversed the NLRB’s factual determination: “The Board’s decision rested on its determination that the Union’s November 2014 counterproposal was a ‘white flag’ of surrender. But the ‘white flag’ characterization in turn rested on an unsound factual foundation from the ALJ” about how unionized employees reacted to a particular compensation system as compared to nonunionized ones. DISH Network Corp. v. NLRB (revised March 24, 2020).

DISH Network declared an impasse after lengthy negotiations with the Communication Workers of America. The NLRB rejected that declaration; the Fifth Circuit reversed the NLRB’s factual determination: “The Board’s decision rested on its determination that the Union’s November 2014 counterproposal was a ‘white flag’ of surrender. But the ‘white flag’ characterization in turn rested on an unsound factual foundation from the ALJ” about how unionized employees reacted to a particular compensation system as compared to nonunionized ones. DISH Network Corp. v. NLRB (revised March 24, 2020).

Surprising no one, the constitutional challenge to the CFPB’s structure presented by CFPB v. All American Check Cashing will be reviewed en banc by the full Fifth Circuit.

Surprising no one, the constitutional challenge to the CFPB’s structure presented by CFPB v. All American Check Cashing will be reviewed en banc by the full Fifth Circuit.

The ground rules for the administrative state are few, important, and vexingly difficult to apply. The en banc court confronted the structure of Fannie Mae’s regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, in Collins v. Mnuchin, 938 F.3d 553 (5th Cir. 2019), and found it wanting constitutionally. In CFPB v. All American Check Cashing, a panel majority confronted the structure of another Great Recession entity, the Consumer Finance Protection Board, and concluded that “neither the text of the Constitution nor the Supreme Court’s previous decisions support the Appellants’ arguments that the CFPB is unconstitutionally structured.” No. 18-60302 (March 3, 2020).

The ground rules for the administrative state are few, important, and vexingly difficult to apply. The en banc court confronted the structure of Fannie Mae’s regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, in Collins v. Mnuchin, 938 F.3d 553 (5th Cir. 2019), and found it wanting constitutionally. In CFPB v. All American Check Cashing, a panel majority confronted the structure of another Great Recession entity, the Consumer Finance Protection Board, and concluded that “neither the text of the Constitution nor the Supreme Court’s previous decisions support the Appellants’ arguments that the CFPB is unconstitutionally structured.” No. 18-60302 (March 3, 2020).

A concurrence elaborated: “The President can remove the CFPB Director only for ‘inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office,’ a broad standard repeatedly approved by the Supreme Court. That alone is enough to decide this case. If there is any threat of undue concentration of power, the Office of President is its beneficiary.” A dissent faulted the majority’s reasoning and the judicial process employed: “Collins winds up in the dustbin because two judges say it should. At one time, those judges thought it beyond the pale ‘to rely on strength in numbers rather than sound legal principles in order to reach their desired result in [a] specific case.’ Now, they suddenly discover that stare decisis is for suckers.” (footnotes omitted).

A concurrence elaborated: “The President can remove the CFPB Director only for ‘inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office,’ a broad standard repeatedly approved by the Supreme Court. That alone is enough to decide this case. If there is any threat of undue concentration of power, the Office of President is its beneficiary.” A dissent faulted the majority’s reasoning and the judicial process employed: “Collins winds up in the dustbin because two judges say it should. At one time, those judges thought it beyond the pale ‘to rely on strength in numbers rather than sound legal principles in order to reach their desired result in [a] specific case.’ Now, they suddenly discover that stare decisis is for suckers.” (footnotes omitted).

The General Land Office of Texas disputed the Interior Department’s decision to continue protection of the golden-cheeked warbler as an endangered species. The Fifth Circuit found the Department’s process flawed: “The Service recited this standard, but a careful examination of its analysis shows that the Service applied an inappropriately heightened one.Specifically, to proceed to the twelve-month review stage, the Service required the delisting petition to contain information that the Service had not considered in its five-year review that was sufficient to refute that review’s conclusions. . . .The Service thus based its decision to deny the delisting petition on an incorrect legal standard. Consequently, we conclude that the Service’s decision was arbitrary and capricious. We therefore vacate that decision and remand for the Service to evaluate the delisting petition under the correct legal standard.” General Land Office of Texas v. U.S. Dep’t of the Interior, No. 19-50178 (Jan. 15, 2020) (emphasis in original).

standard, but a careful examination of its analysis shows that the Service applied an inappropriately heightened one.Specifically, to proceed to the twelve-month review stage, the Service required the delisting petition to contain information that the Service had not considered in its five-year review that was sufficient to refute that review’s conclusions. . . .The Service thus based its decision to deny the delisting petition on an incorrect legal standard. Consequently, we conclude that the Service’s decision was arbitrary and capricious. We therefore vacate that decision and remand for the Service to evaluate the delisting petition under the correct legal standard.” General Land Office of Texas v. U.S. Dep’t of the Interior, No. 19-50178 (Jan. 15, 2020) (emphasis in original).

A Chevron dispute about the Department of the Interior’s collection of natural gas royalties led to the question whether “the agency must credit all of W&T’s prior overdeliveries in calculating the cumulative delivery shortfall.” Observing that the defense of “equitable recoupment is ‘never barred by the statute of limitations so long as the main action itself is timely,'” the Fifth Circuit rejected the Department’s three arguments against its application – looking to three common reference points for resolving such disputes:

A Chevron dispute about the Department of the Interior’s collection of natural gas royalties led to the question whether “the agency must credit all of W&T’s prior overdeliveries in calculating the cumulative delivery shortfall.” Observing that the defense of “equitable recoupment is ‘never barred by the statute of limitations so long as the main action itself is timely,'” the Fifth Circuit rejected the Department’s three arguments against its application – looking to three common reference points for resolving such disputes:

- Statutory limitations. A statutory prohibition on “pursu[it of] any other equitable or legal remedy, whether under statute or common law” did not clearly preclude the assertion of this defense;

- Factual linkage. “This objection is easily dispatched, as the Department of the Interior’s requirement that payments be made on a monthly basis does not trump the reality that each monthly obligation arises from a single contract: the lease.

- Overall equities. The Department’s facially “neutral application of the statute of limitations across the industry does not counteract the inequitable result that W&T suffered . . . .”

W&T Offshore v. Bernhardt, No. 18-30876 (Dec. 23, 2019).

The Fifth Circuit affirmed a Tax Court decision about a $52 million “bad debt” deduction, observing: “Baker Hughes’ authorities all involved a bona fide debt. … No authority shown to us holds that a bad-debt deduction applies to a guarantor’s payment on a guarantee that does not create a debtor-creditor relationship with the party whose original obligation is extinguished.” Baker Hughes Inc. v. United States, No. 18-20585 (Nov. 21, 2019).

The Fifth Circuit affirmed a Tax Court decision about a $52 million “bad debt” deduction, observing: “Baker Hughes’ authorities all involved a bona fide debt. … No authority shown to us holds that a bad-debt deduction applies to a guarantor’s payment on a guarantee that does not create a debtor-creditor relationship with the party whose original obligation is extinguished.” Baker Hughes Inc. v. United States, No. 18-20585 (Nov. 21, 2019).

The Fifth Circuit reversed an OSHA determination that a company had failed to justify an untimely response, noting that under Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(1) (which OSHA has adopted for this particular situation): “The excusable neglect inquiry is not limited to whether a party’s mistake caused the delay, such cause being expressed in the term ‘neglect,’ but equally concerns whether the party’s mistake or omission was ‘excusable.’ Focusing narrowly on whether a party is at fault for the delay and denying relief if it bears any blame clearly conflicts with Pioneer‘s more lenient and comprehensive standard.” Coleman Hammons Constr. Co. v. OSHA, No. 18-60559 (Nov. 6, 2019).

The Fifth Circuit reversed an OSHA determination that a company had failed to justify an untimely response, noting that under Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(1) (which OSHA has adopted for this particular situation): “The excusable neglect inquiry is not limited to whether a party’s mistake caused the delay, such cause being expressed in the term ‘neglect,’ but equally concerns whether the party’s mistake or omission was ‘excusable.’ Focusing narrowly on whether a party is at fault for the delay and denying relief if it bears any blame clearly conflicts with Pioneer‘s more lenient and comprehensive standard.” Coleman Hammons Constr. Co. v. OSHA, No. 18-60559 (Nov. 6, 2019).

The EPA approved Louisiana’s plan for controlling haze; both environmental and industry groups protested. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the EPA’s approval under the “arbitrary and capricious” standard of review.

The EPA approved Louisiana’s plan for controlling haze; both environmental and industry groups protested. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the EPA’s approval under the “arbitrary and capricious” standard of review.

As to industry: “We afford ‘significant deference’ to agency decisions involving analysis of scientific data within the agency’s technical expertise. The EPA’s selection of a model to measure air pollution levels is precisely that type of decision. The EPA therefore did not act arbitrarily and capriciously in relying on the CALPUFF model to approve Louisiana’s [statutorily-required] determinations.”

As to environmental groups: “Louisiana’s explanation of its . . . determination . . . omitted two of the five mandatory factors and failed to compare—or even set out—the numbers for the costs and benefits of the control options Louisiana considered. Louisiana also failed to explain how its decision accounted for the EPA-submitted analyses that pointed out substantial flaws in other analyses in the administrative record. But applying the deferential standards of the Administrative Procedures Act to the facts of this case, we hold that the EPA’s approval of Louisiana’s [plan] was not arbitrary and capricious.” Sierra Club v. EPA, No. 18-60116 (Oct. 3, 2019).

The full Fifth Circuit engaged the boundaries of the administrative state in Collins v. Mnuchin. A 9-7 majority of the en banc Court found that the FHFA (the regulator of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) was structured unconstitutionally; a different 9-7 majority found that the appropriate remedy was a go-forward restructure of the agency rather than the unwinding of a significant, previously-ordered financial transaction. (If the below is hard to read in your browser, just click on it to see it full-sized).

The full Fifth Circuit engaged the boundaries of the administrative state in Collins v. Mnuchin. A 9-7 majority of the en banc Court found that the FHFA (the regulator of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) was structured unconstitutionally; a different 9-7 majority found that the appropriate remedy was a go-forward restructure of the agency rather than the unwinding of a significant, previously-ordered financial transaction. (If the below is hard to read in your browser, just click on it to see it full-sized).

Four Republican appointees joined the majority on remedy, two of whom–Judges Owen and Duncan–had joined the majority on constitutionality.

Four Republican appointees joined the majority on remedy, two of whom–Judges Owen and Duncan–had joined the majority on constitutionality.

Among the various concurrences and dissents, Judges Ho and Oldham concurred to emphasize the significance of the case to other administrative agencies, while Judges Costa and Higginson dissented on the basis of the plaintiffs’ standing.

The diverse approaches of the Republican-appointed judges underscore the frequent observation on this blog that the term “conservative” is a broad umbrella for different perspectives on distinct aspects of the apparatus of government.

Conservative thinkers frequently express skepticism about the administrative state, and in particular, the Chevron doctrine about judicial deference to it. A powerful counterpoint to that line of thinking, and an equally orthodox part of conservative philosophy, appears in the Fifth Circuit’s recent opinion in Center for Biological Diversity v. EPA, which found a lack of standing to challenge an EPA discharge permit and reminded: “’For the federal courts to decide questions of law arising outside of cases and controversies would be inimical to the Constitution’s democratic character.’ It would improperly transform courts into ‘roving commissions assigned to pass judgment on the validity of the Nation’s laws’ and agency actions. In our Government, there are entities that address environmental issues outside of the case-or-controversy constraint. This Court is not one of them. As Judge Sentelle put it many years ago: ‘The federal judiciary is not a backseat Congress nor some sort of super-agency.’“ No. 18-60102 (Aug. 30, 2019) (citations omitted).

Conservative thinkers frequently express skepticism about the administrative state, and in particular, the Chevron doctrine about judicial deference to it. A powerful counterpoint to that line of thinking, and an equally orthodox part of conservative philosophy, appears in the Fifth Circuit’s recent opinion in Center for Biological Diversity v. EPA, which found a lack of standing to challenge an EPA discharge permit and reminded: “’For the federal courts to decide questions of law arising outside of cases and controversies would be inimical to the Constitution’s democratic character.’ It would improperly transform courts into ‘roving commissions assigned to pass judgment on the validity of the Nation’s laws’ and agency actions. In our Government, there are entities that address environmental issues outside of the case-or-controversy constraint. This Court is not one of them. As Judge Sentelle put it many years ago: ‘The federal judiciary is not a backseat Congress nor some sort of super-agency.’“ No. 18-60102 (Aug. 30, 2019) (citations omitted).

The complexity of the modern administrative state produces ornate procedural problems – specifically, in Wynnewood Refining Co. v. OSHRC, the challenge of two parties appealing an administrative-agency ruling to two different federal circuit courts. The solution, however, is simple, in the form of a strict “first-to-file” rule established by Congress for this problem: “Th[is] first-to-file rule governs even for petitions filed on the same day; indeed, we have applied it even when petitions were filed within a minute of each other.” The Fifth Circuit rebuffed an attempt by the agency to assert its discretion over which petition was filed first, concluding that Congress had drafted this statute to foreclose precisely such discretion. No. 19-60357 (Aug. 2, 2019).

In Brackeen v. Bernhardt, an opinion of enormous significance to Indian law, the Fifth Circuit found the Indian Child Welfare Act to be constitutional, reversing a district-court opinion that held otherwise. The Court also affirmed various Bureau of Indian Affairs regulations under the Chevron doctrine, noting, inter alia: “The mere fact that an agency interpretation contradicts a prior agency position is not fatal. Sudden and

In Brackeen v. Bernhardt, an opinion of enormous significance to Indian law, the Fifth Circuit found the Indian Child Welfare Act to be constitutional, reversing a district-court opinion that held otherwise. The Court also affirmed various Bureau of Indian Affairs regulations under the Chevron doctrine, noting, inter alia: “The mere fact that an agency interpretation contradicts a prior agency position is not fatal. Sudden and  unexplained change, or change that does not take account of legitimate reliance on prior interpretation, may be arbitrary, capricious [or] an abuse of discretion. But if these pitfalls are avoided, change is not invalidating, since the whole point of Chevron is to leave the discretion provided by the ambiguities of a statute with the implementing agency.” No. 18-11479 (Aug. 9, 2019) (citation omitted). (My colleague Paulette Miniter and I assisted Professor Seth Davis of UC-Berkeley with an amicus brief in this case, in support of the result ultimately reached by the Court.)

unexplained change, or change that does not take account of legitimate reliance on prior interpretation, may be arbitrary, capricious [or] an abuse of discretion. But if these pitfalls are avoided, change is not invalidating, since the whole point of Chevron is to leave the discretion provided by the ambiguities of a statute with the implementing agency.” No. 18-11479 (Aug. 9, 2019) (citation omitted). (My colleague Paulette Miniter and I assisted Professor Seth Davis of UC-Berkeley with an amicus brief in this case, in support of the result ultimately reached by the Court.)

After a recent en banc vote, the full Fifth Circuit will engage an important limit on the power of the administrative state. The majority and dissenting opinons in Sierra Club v. Luminant Energy grappled with the “concurrent-remedies doctrine” and whether it created a limitations bar to an action for equitable relief under the Clean Air Act. No. No. 17-10235 (order issued June 10, 2019).

After a recent en banc vote, the full Fifth Circuit will engage an important limit on the power of the administrative state. The majority and dissenting opinons in Sierra Club v. Luminant Energy grappled with the “concurrent-remedies doctrine” and whether it created a limitations bar to an action for equitable relief under the Clean Air Act. No. No. 17-10235 (order issued June 10, 2019).

In a detailed (and remarkably readable) review of EPA regulations of water pollution by steam-electric power plants, the Fifth Circuit vacated and remanded a rule for further agency consideration. In a nutshell: “[F]or five of the six wastewater streams regulated by the final rule . . ., EPA affirmatively rejected surface impoundments as [“Best Available Technology”] ‘because [they] would not result in reasonable further progress toward eliminating the discharge of all pollutants, particularly toxic pollutants.’ And yet, having rejected impoundments as BAT because they would not achieve ‘reasonable further progress’ toward eliminating pollution from those streams, EPA turned around and chose impoundments as BAT for each of those same streams generated before the compliance date. That paradoxical action signals arbitrary and capricious agency action.” (emphasis added, citations omitted). Southwestern Elec. Power Co. v. EPA, No. 15-60821 (April 12, 2019).

In a detailed (and remarkably readable) review of EPA regulations of water pollution by steam-electric power plants, the Fifth Circuit vacated and remanded a rule for further agency consideration. In a nutshell: “[F]or five of the six wastewater streams regulated by the final rule . . ., EPA affirmatively rejected surface impoundments as [“Best Available Technology”] ‘because [they] would not result in reasonable further progress toward eliminating the discharge of all pollutants, particularly toxic pollutants.’ And yet, having rejected impoundments as BAT because they would not achieve ‘reasonable further progress’ toward eliminating pollution from those streams, EPA turned around and chose impoundments as BAT for each of those same streams generated before the compliance date. That paradoxical action signals arbitrary and capricious agency action.” (emphasis added, citations omitted). Southwestern Elec. Power Co. v. EPA, No. 15-60821 (April 12, 2019).

A 1994 Fifth Circuit opinion addressed whether the “Indian Tribes of Texas Restoration Act” or the “Indian Gaming Restoration Act” controlled Indian gaming in Texas (answer, the Restoration Act). In 2015, the National Indian Gaming Commission, citing intervening Supreme Court precedent, ruled otherwise. The Fifth Circuit declined to extend Chevron deference to that later ruling, noting:

A 1994 Fifth Circuit opinion addressed whether the “Indian Tribes of Texas Restoration Act” or the “Indian Gaming Restoration Act” controlled Indian gaming in Texas (answer, the Restoration Act). In 2015, the National Indian Gaming Commission, citing intervening Supreme Court precedent, ruled otherwise. The Fifth Circuit declined to extend Chevron deference to that later ruling, noting:

“[This case] requires us to apply Chevron step one to a prior judicial interpretation and to determine whether that court employed traditional tools of statutory interpretation and found that Congress spoke to the precise issue. That is what Ysleta I did in holding that “the Restoration Act prevails over IGRA when gaming activities proposed by [the Pueblo or Tribe] are at issue. Consequently, the NIGC’s decision that IGRA applies to the Tribe does not displace Ysleta I.”

State v. Alabama-Coushatta Tribe, No. 18-40116 (March 14, 2019).

In Louisiana Real Estate Appraisers Board v. FTC, the Fifth Circuit declined to apply the “collateral order” doctrine to an interlocutory order of an administrative agency, leaving open the possibility that the doctrine could so be applied in a different situation. No. 18-60291 (Feb. 28, 2019).

In Louisiana Real Estate Appraisers Board v. FTC, the Fifth Circuit declined to apply the “collateral order” doctrine to an interlocutory order of an administrative agency, leaving open the possibility that the doctrine could so be applied in a different situation. No. 18-60291 (Feb. 28, 2019).

The fractured panel in Collins v. Mnuchin, which addressed the legality of “sweeps” of funds from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac by their regulator, led to a fascinating en banc argument today in New Orleans as the Court reviewed fundamental administrative-law issues.

The fractured panel in Collins v. Mnuchin, which addressed the legality of “sweeps” of funds from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac by their regulator, led to a fascinating en banc argument today in New Orleans as the Court reviewed fundamental administrative-law issues.

The dusky gopher frog returns to the Fifth Circuit; the Supreme Court has reversed a decision about judicial review of the Fish & Wildlife Service’s treatment of the endangered frog’s habitat, reached after a close denial of en banc review. In the meantime, the Fifth Circuit’s makeup has materially changed in ways that likely predispose the full court toward a different view of the underlying administrative-law issues.

The dusky gopher frog returns to the Fifth Circuit; the Supreme Court has reversed a decision about judicial review of the Fish & Wildlife Service’s treatment of the endangered frog’s habitat, reached after a close denial of en banc review. In the meantime, the Fifth Circuit’s makeup has materially changed in ways that likely predispose the full court toward a different view of the underlying administrative-law issues.

Even in the complex world of the modern administrative state, the Social Security Administration stands alone as “the Mount Everest of bureaucratic structures.” Barrett v. Berryhill, No. 17-41177 (revised Oct. 16, 2018) (citation omitted). Surveying that landscape, the Fifth Circuit concluded that a person claiming disability benefits did not have an automatic right to cross-examine a “medical consultant,” a doctor who reviews records without examining the claimant: “We do not mean to say that the opinions of medical consultants are unimportant or error free. But granting an automatic right to subpoena them is too strong a medicine. We do not see why examination of a medical consultant will always, or even usually, lead to meaningful impeachment. That is especially true when, as in this case, the [relevant] form is reviewed by a second medical consultant, lessening the risk of error. When a claimant has legitimate concerns that a[] . . . form is inaccurate or misleading, existing regulations provide the opportunity to question the drafter.” (emphasis in original).

Even in the complex world of the modern administrative state, the Social Security Administration stands alone as “the Mount Everest of bureaucratic structures.” Barrett v. Berryhill, No. 17-41177 (revised Oct. 16, 2018) (citation omitted). Surveying that landscape, the Fifth Circuit concluded that a person claiming disability benefits did not have an automatic right to cross-examine a “medical consultant,” a doctor who reviews records without examining the claimant: “We do not mean to say that the opinions of medical consultants are unimportant or error free. But granting an automatic right to subpoena them is too strong a medicine. We do not see why examination of a medical consultant will always, or even usually, lead to meaningful impeachment. That is especially true when, as in this case, the [relevant] form is reviewed by a second medical consultant, lessening the risk of error. When a claimant has legitimate concerns that a[] . . . form is inaccurate or misleading, existing regulations provide the opportunity to question the drafter.” (emphasis in original).

The modern administrative state often requests documents for compliance and enforcement purposes; such a request led to a Fourth Amendment challenge to a subpoena from the Texas Medical Board in Barry v. Freshour. The challenge was made by a doctor who practiced at the facility that received the request. The Fifth Circuit rejected the doctor’s challenge and reversed the district court’s ruling in his favor: “The district court concluded Barry had standing because the records were sought in a proceeding against him and the subpoena was addressed to him personally (though it was also addressed to the records custodian). But the Supreme Court has rejected a ‘target’ approach to Fourth Amendment standing that would look to whether the evidence obtained could be used against the person seeking to challenge the search.” Here, “Barry relies on a list of pure privacy interests in the information the records contain. All but one, as he concedes, are specifically tied to his patients’ privacy interests in their own medical records. To the extent such interests are constitutionally cognizable, they cannot be asserted by Barry.” No. 17-20726 (Oct. 4, 2018).

The modern administrative state often requests documents for compliance and enforcement purposes; such a request led to a Fourth Amendment challenge to a subpoena from the Texas Medical Board in Barry v. Freshour. The challenge was made by a doctor who practiced at the facility that received the request. The Fifth Circuit rejected the doctor’s challenge and reversed the district court’s ruling in his favor: “The district court concluded Barry had standing because the records were sought in a proceeding against him and the subpoena was addressed to him personally (though it was also addressed to the records custodian). But the Supreme Court has rejected a ‘target’ approach to Fourth Amendment standing that would look to whether the evidence obtained could be used against the person seeking to challenge the search.” Here, “Barry relies on a list of pure privacy interests in the information the records contain. All but one, as he concedes, are specifically tied to his patients’ privacy interests in their own medical records. To the extent such interests are constitutionally cognizable, they cannot be asserted by Barry.” No. 17-20726 (Oct. 4, 2018).

The “concurrent-remedies doctrine” holds that “when the jurisdiction of the federal court is concurrent with that of law, or the suit is brought in aid of a legal right, equity will withhold its remedy if the legal right is barred by the local statute of limitations.” In Sierra Club v. Luminant Energy, that doctrine would have barred a private litigant’s claim for an injunction when a damages claim was time-barred – but it was held not to apply to a request for injunctive relief brought by the U.S. in its capacity as sovereign. On the

The “concurrent-remedies doctrine” holds that “when the jurisdiction of the federal court is concurrent with that of law, or the suit is brought in aid of a legal right, equity will withhold its remedy if the legal right is barred by the local statute of limitations.” In Sierra Club v. Luminant Energy, that doctrine would have barred a private litigant’s claim for an injunction when a damages claim was time-barred – but it was held not to apply to a request for injunctive relief brought by the U.S. in its capacity as sovereign. On the  merits of the request, the panel majority noted that “the statute of limitations that barred the legal relief [of damages] does not itself bar equitable relief unless it constitutes a penalty,” and left the question of whether the relief was in fact a penalty for the district court on remand. A dissent reasoned that “both of these so-called forms of injunctive relief are really just time-barred penalties in disguise,” would have affirmed dismissal of the entire case on limitations grounds, and avoided the issue about applying the concurrent-remedies doctrine to sovereigns. No. 17-10235 (Oct. 1, 2018).

merits of the request, the panel majority noted that “the statute of limitations that barred the legal relief [of damages] does not itself bar equitable relief unless it constitutes a penalty,” and left the question of whether the relief was in fact a penalty for the district court on remand. A dissent reasoned that “both of these so-called forms of injunctive relief are really just time-barred penalties in disguise,” would have affirmed dismissal of the entire case on limitations grounds, and avoided the issue about applying the concurrent-remedies doctrine to sovereigns. No. 17-10235 (Oct. 1, 2018).

After a thorough review of the “fundamental relationship between a relator and the Government in qui tam actions,” the Fifth Circuit concluded that private relators dismissal of an action with prejudice did not bind the non-intervening U.S. government: “[R]elators sought to abandon their claims because they no longer wished to participate in the litigation. In other words, they acted on purely private interests. The Government—even one that chooses not to intervene—should not be bound by this decision, powerless to vindicate the public’s interests in other actions that may have a stronger basis or a relator more able to shoulder the burdens of litigation.” U.S. ex rel. Vaughn v. United Biologics LLC, No. 17-20389 (Sept. 7, 2018).

After a thorough review of the “fundamental relationship between a relator and the Government in qui tam actions,” the Fifth Circuit concluded that private relators dismissal of an action with prejudice did not bind the non-intervening U.S. government: “[R]elators sought to abandon their claims because they no longer wished to participate in the litigation. In other words, they acted on purely private interests. The Government—even one that chooses not to intervene—should not be bound by this decision, powerless to vindicate the public’s interests in other actions that may have a stronger basis or a relator more able to shoulder the burdens of litigation.” U.S. ex rel. Vaughn v. United Biologics LLC, No. 17-20389 (Sept. 7, 2018).

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau – the subject of ongoing litigation about the constitutionality of its structure, which has been at issue in the recent Kavanaugh hearings – lost a challenge to a civil investigative demand in CFPB v. The Source for Public Data: “The CFPB did not comply with 12 U.S.C. § 5562(c)(2) when it issued this CID to Public Data. First, it did not state the ‘conduct constituting the alleged violation which is under investigation.’ According to its Notification of Purpose, the CFPB is investigating ‘unlawful acts and practices in connection with the provision or use of public records information.’ Simply put, this Notification of Purpose does not identify what conduct, it believes, constitutes an alleged violation. . . . Moreover, this CID does not identify ‘the provision of law applicable to such violation.’ As discussed, the CID never identifies an alleged violation, so it is unsurprising that it fails to identify a relevant provision of law.” No. 17-10732 (Sept. 6, 2018).

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau – the subject of ongoing litigation about the constitutionality of its structure, which has been at issue in the recent Kavanaugh hearings – lost a challenge to a civil investigative demand in CFPB v. The Source for Public Data: “The CFPB did not comply with 12 U.S.C. § 5562(c)(2) when it issued this CID to Public Data. First, it did not state the ‘conduct constituting the alleged violation which is under investigation.’ According to its Notification of Purpose, the CFPB is investigating ‘unlawful acts and practices in connection with the provision or use of public records information.’ Simply put, this Notification of Purpose does not identify what conduct, it believes, constitutes an alleged violation. . . . Moreover, this CID does not identify ‘the provision of law applicable to such violation.’ As discussed, the CID never identifies an alleged violation, so it is unsurprising that it fails to identify a relevant provision of law.” No. 17-10732 (Sept. 6, 2018).

Federal crop insurance “protects an asset that does not yet exist,” since future crops are not yet grown. Congress refined the applicable statutes in 2014, allowing farmers to “elect to exclude” certain low-production

Federal crop insurance “protects an asset that does not yet exist,” since future crops are not yet grown. Congress refined the applicable statutes in 2014, allowing farmers to “elect to exclude” certain low-production  years from the historical calculations needed to write insurance for future crop production. The relevant amendment applied “for any of the 2001 and subsequent crop years,” and became effective immediately. A dispute arose between Texas winter wheat farmers, who announced their intention to exclude years under this statute, and the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation, who said it lacked time to prepare the necessary data. The Fifth Circuit rejected the FCIC’s argument that this statute’s “effective” date was distinct from its “implementation” date, finding that it failed step one of Chevron – “Such a problem arises not from an ambiguous

years from the historical calculations needed to write insurance for future crop production. The relevant amendment applied “for any of the 2001 and subsequent crop years,” and became effective immediately. A dispute arose between Texas winter wheat farmers, who announced their intention to exclude years under this statute, and the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation, who said it lacked time to prepare the necessary data. The Fifth Circuit rejected the FCIC’s argument that this statute’s “effective” date was distinct from its “implementation” date, finding that it failed step one of Chevron – “Such a problem arises not from an ambiguous  text but from Congress implementing razor sharp deadlines without, at least according to the FCIC, sufficient resources. That does not give the FCIC authority to disregard the plain text of the statute . . . .” Adkins v. Silverman, No. 17-10759 (Aug. 7, 2018).

text but from Congress implementing razor sharp deadlines without, at least according to the FCIC, sufficient resources. That does not give the FCIC authority to disregard the plain text of the statute . . . .” Adkins v. Silverman, No. 17-10759 (Aug. 7, 2018).

A difficult question of administrative law produced a divided panel in Collins v. Mnuchin. The panel majority concluded that the Federal Housing Finance Agency (a regulator for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac created by Congress in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis) was unconstitutionally structured. After careful review of the Supreme Court’s precedents in the area, the panel excised a “for cause” limitation on the removal of FHFA’s director from the relevant statute, finding that with this revision “the FHFA survives as a properly supervised executive agency.” One dissent took issue with that holding; another dissent criticized the majority’s conclusion that the specific FHFA action at issue – a “net worth sweep” requiring payment of substantial quarterly dividends to the Treasury by Fannie and Freddie – was within the scope of FHFA’s statutory authority and thus insulated from judicial review. No. 17-20364 (July 16, 2018).

A difficult question of administrative law produced a divided panel in Collins v. Mnuchin. The panel majority concluded that the Federal Housing Finance Agency (a regulator for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac created by Congress in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis) was unconstitutionally structured. After careful review of the Supreme Court’s precedents in the area, the panel excised a “for cause” limitation on the removal of FHFA’s director from the relevant statute, finding that with this revision “the FHFA survives as a properly supervised executive agency.” One dissent took issue with that holding; another dissent criticized the majority’s conclusion that the specific FHFA action at issue – a “net worth sweep” requiring payment of substantial quarterly dividends to the Treasury by Fannie and Freddie – was within the scope of FHFA’s statutory authority and thus insulated from judicial review. No. 17-20364 (July 16, 2018).

Many years, ago, “the Supreme Court viewed the fashioning of statutory remedies as within the property judicial rule [u]nder the now-abandoned maxim that ‘a statutory right implies the existence of all necessary and appropriate remedies.'” But that view has changed, and now, “the judicial task is to interpret the statute Congress has passed.” Alexander v. Sandoval, 532 U.S. 275 (2001). Proceeding from that starting point, after a review of the text and structure of the Air Carrier Access Act of 1986, the Court agreed that the Act did not create a private right of action, and it recognized that earlier Circuit authority on the issue had been essentially overruled by the analytical framework in Sandoval. Stokes v. Southwest Airlines, No. 17-10760 (April 5, 2018).

Many years, ago, “the Supreme Court viewed the fashioning of statutory remedies as within the property judicial rule [u]nder the now-abandoned maxim that ‘a statutory right implies the existence of all necessary and appropriate remedies.'” But that view has changed, and now, “the judicial task is to interpret the statute Congress has passed.” Alexander v. Sandoval, 532 U.S. 275 (2001). Proceeding from that starting point, after a review of the text and structure of the Air Carrier Access Act of 1986, the Court agreed that the Act did not create a private right of action, and it recognized that earlier Circuit authority on the issue had been essentially overruled by the analytical framework in Sandoval. Stokes v. Southwest Airlines, No. 17-10760 (April 5, 2018).

By a 2-1 opinion, in Chamber of Commerce v. U.S. Dep’t of Labor, the Fifth Circuit struck down the “Fiduclary Rule,” a regulation that significantly expanded regulation of investment advisors. The majority’s analysis focused primarily on the traditional definition of a “fiduciary” (a discussion of broad general interest to all business litigators), and the canon of interpretation that “provisions of a text should be interpreted in a way that renders them compatible, not contradictory.” The dissent focused on how, “[o]ver the last forty years, the retirement-investment market has experienced a dramatic shift toward individually controlled retirement plans and accounts.” Notably, footnote 14 of the majority opinion observes that “the Chevron doctrine has been questioned on substantial grounds, including that it represents an abdication of the judiciary’s’ duty under Article III ‘to say what the law is,'” quoting recent opinions my Justice Thomas and then-Judge Gorsuch. No. 17-10238 (March 15, 2018).

By a 2-1 opinion, in Chamber of Commerce v. U.S. Dep’t of Labor, the Fifth Circuit struck down the “Fiduclary Rule,” a regulation that significantly expanded regulation of investment advisors. The majority’s analysis focused primarily on the traditional definition of a “fiduciary” (a discussion of broad general interest to all business litigators), and the canon of interpretation that “provisions of a text should be interpreted in a way that renders them compatible, not contradictory.” The dissent focused on how, “[o]ver the last forty years, the retirement-investment market has experienced a dramatic shift toward individually controlled retirement plans and accounts.” Notably, footnote 14 of the majority opinion observes that “the Chevron doctrine has been questioned on substantial grounds, including that it represents an abdication of the judiciary’s’ duty under Article III ‘to say what the law is,'” quoting recent opinions my Justice Thomas and then-Judge Gorsuch. No. 17-10238 (March 15, 2018).

Welding-safety regulations enacted under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act contain this definition: “You means a lessee, the owner or holder of operating rights, a designated operator or agent of the lessee(s), a pipeline right-of-way holder, or a State lesssee granted a right-of-use and easement.” In United States v. Moss, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of criminal charges against a contractor based on this set of regulations, agreeing that “you” – as defined above, and applied consistently with relevant canons of interpretation – could not be read to include a contractor. Weighing heavily against the government’s position was a long history of “virtually non-existent past enforcement of OCSLA regulations against contractors.” No. 16-30561 (Sept. 27, 2017).

Welding-safety regulations enacted under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act contain this definition: “You means a lessee, the owner or holder of operating rights, a designated operator or agent of the lessee(s), a pipeline right-of-way holder, or a State lesssee granted a right-of-use and easement.” In United States v. Moss, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of criminal charges against a contractor based on this set of regulations, agreeing that “you” – as defined above, and applied consistently with relevant canons of interpretation – could not be read to include a contractor. Weighing heavily against the government’s position was a long history of “virtually non-existent past enforcement of OCSLA regulations against contractors.” No. 16-30561 (Sept. 27, 2017).

2017 has not been kind to the administrative state, and neither was Burgess v. FDIC, No. 17-60579 (Sept. 7, 2017). An FDIC administrative law judge concluded that Burgess had misused bank property, the FDIC Board adopted those recommendations, and Burgess sought review in the Fifth Circuit. He sought an interim stay based upon his argument that the ALJ was an “inferior Officer” within the meaning of the Constitution’s Appointments Clause, and the Fifth Circuit agreed, citing the Supreme Court’s analysis of a similar position involving the U.S. Tax Court in Freytag v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 501 U.S. 868 (1991). In so doing, the Court parted ways with the D.C. Circuit’s analysis in Landry v. FDIC, 204 F.3d 1125 (2000), by concluding that final decision-making authority was not a prerequisite to Officer status. Accordingly, the Court granted the interim stay, finding that Burgess “has established a likelihood of success on the merits of his Appointments Clause challenge.”

2017 has not been kind to the administrative state, and neither was Burgess v. FDIC, No. 17-60579 (Sept. 7, 2017). An FDIC administrative law judge concluded that Burgess had misused bank property, the FDIC Board adopted those recommendations, and Burgess sought review in the Fifth Circuit. He sought an interim stay based upon his argument that the ALJ was an “inferior Officer” within the meaning of the Constitution’s Appointments Clause, and the Fifth Circuit agreed, citing the Supreme Court’s analysis of a similar position involving the U.S. Tax Court in Freytag v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 501 U.S. 868 (1991). In so doing, the Court parted ways with the D.C. Circuit’s analysis in Landry v. FDIC, 204 F.3d 1125 (2000), by concluding that final decision-making authority was not a prerequisite to Officer status. Accordingly, the Court granted the interim stay, finding that Burgess “has established a likelihood of success on the merits of his Appointments Clause challenge.”

After a pipeline breach, a federal regulator penalized ExxonMobil for violating safety rules. The Fifth Circuit reversed, finding, inter alia, that the agency’s interpretation of the “textually unambiguous” regulation required no deference under Auer v. Robbins, 519 U.S. 452 (1997). Specifically, the regulation said that pipeline operators “must consider” “all risk factors that reflect the risk conditions on the pipeline

After a pipeline breach, a federal regulator penalized ExxonMobil for violating safety rules. The Fifth Circuit reversed, finding, inter alia, that the agency’s interpretation of the “textually unambiguous” regulation required no deference under Auer v. Robbins, 519 U.S. 452 (1997). Specifically, the regulation said that pipeline operators “must consider” “all risk factors that reflect the risk conditions on the pipeline  segment.” Concluding (presumably, after due consideration), that “consider” meant “to think about carefully,” the Court concluded that the regulation “unambiguously serves to informs a pipeline operator’s careful and deliberate decision-making process rather than to compel a particular outcome . . . ” This conclusion undermined the substantive basis of the agency’s liability determination, and led to reversal in substantial part. ExxonMobil Pipeline Co. v. U.S. Dep’t of Transp., No. 16-60448 (Aug. 14, 2017).

segment.” Concluding (presumably, after due consideration), that “consider” meant “to think about carefully,” the Court concluded that the regulation “unambiguously serves to informs a pipeline operator’s careful and deliberate decision-making process rather than to compel a particular outcome . . . ” This conclusion undermined the substantive basis of the agency’s liability determination, and led to reversal in substantial part. ExxonMobil Pipeline Co. v. U.S. Dep’t of Transp., No. 16-60448 (Aug. 14, 2017).

In Hills v. Entergy Operations, Inc., a case about overtime pay for security guards, the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment based upon a conclusion about two guards’ lack of damage. While the Court’s holding was based upon technical issues of employment law, its underlying reasoning is of broader applicability: “We reverse the district court’s summary judgment that the fluctuating workweek method applies here as a matter of law. The underlying factual issue upon which the applicabilty of that method is predicated, what the employees clearly understood, should be decided at trial in due course.” No. 16-30924 (Aug. 4, 2017). Also, in a ruling of general interest about administrative law, the Court declined to follow an interpretive letter by the Department of Labor.

In Hills v. Entergy Operations, Inc., a case about overtime pay for security guards, the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment based upon a conclusion about two guards’ lack of damage. While the Court’s holding was based upon technical issues of employment law, its underlying reasoning is of broader applicability: “We reverse the district court’s summary judgment that the fluctuating workweek method applies here as a matter of law. The underlying factual issue upon which the applicabilty of that method is predicated, what the employees clearly understood, should be decided at trial in due course.” No. 16-30924 (Aug. 4, 2017). Also, in a ruling of general interest about administrative law, the Court declined to follow an interpretive letter by the Department of Labor.