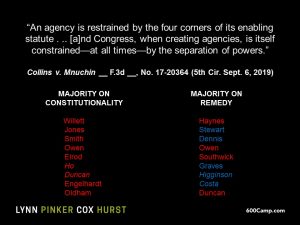

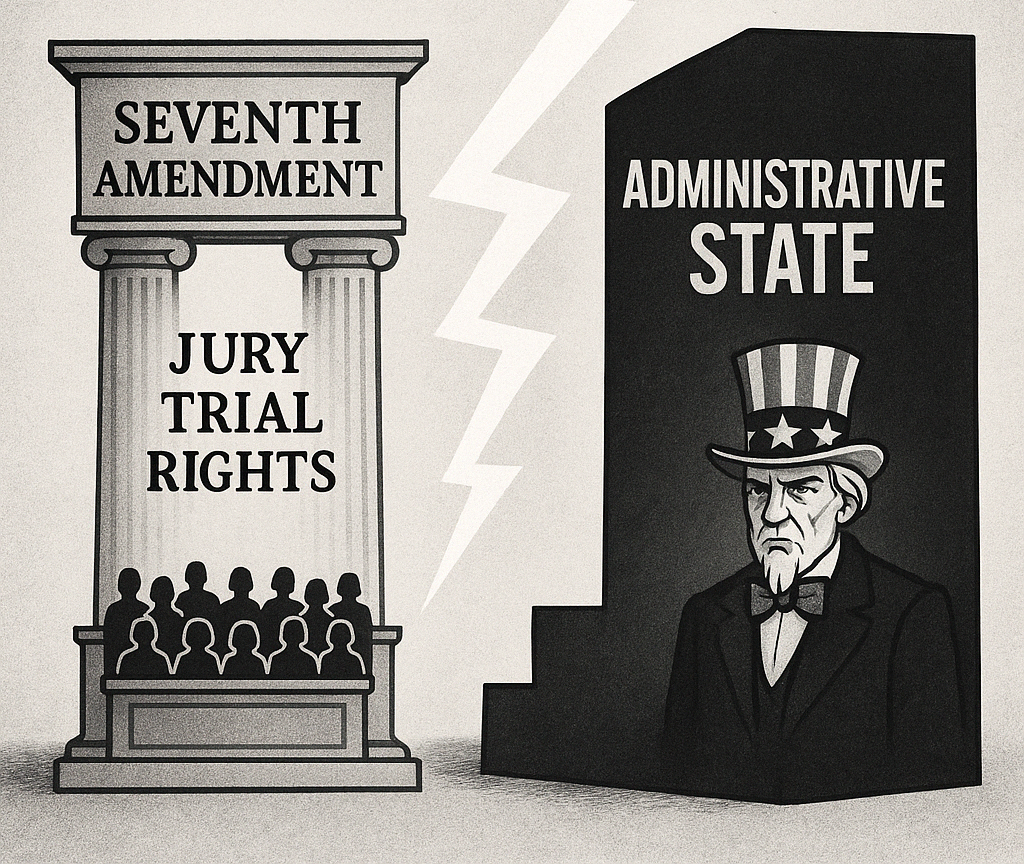

After affirmance of the Fifth Circuit in SEC v. Jarkesy, that Court returned to the interaction between the Seventh Amendment and the admininistrative state in AT&T Inc. v. FCC. The specific issue was whether the FCC’s in-house enforcement procedures for imposing civil penalties violate the constitutional right to a jury trial, as clarified by Jarkesy.

After affirmance of the Fifth Circuit in SEC v. Jarkesy, that Court returned to the interaction between the Seventh Amendment and the admininistrative state in AT&T Inc. v. FCC. The specific issue was whether the FCC’s in-house enforcement procedures for imposing civil penalties violate the constitutional right to a jury trial, as clarified by Jarkesy.

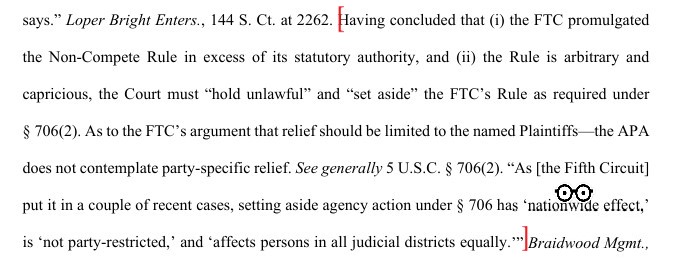

The court held that the FCC’s process ran afoul of the Seventh Amendment, emphasizing that these civil penalties are “the prototypical common law remedy,” designed to punish or deter, and thus “a type of remedy at common law that could only be enforced in courts of law.” In particular, and FCC enforcement action under section 222 of the Telecommunications Act resembles a negligence action, as it centers on whether the carrier took “reasonable measures” to protect customer data, notwithstanding the technical nature of the factual situation.

The Court also rejected the FCC’s argument that the availability of a later trial in federal court—after the agency has already found liability and imposed penalties—satisfies the Seventh Amendment. In such a trial, explained the Court, the defendant cannot challenge the legal conclusions of the agency, only the factual basis, and that this structure forces companies to choose between a jury trial and the ability to challenge the legality of the order. No. 24-60223, Apr. 17, 2025. (A third judge concurred without opinion).