This Instagram video with fonts talking to each other is really funny. Thanks to my law partner Mary Nix for sending it my way.

Monthly Archives: January 2024

Rolex Watch USA, Inc. v Beckertime, LLC affirmed a finding of infringement, while also affirming the trial court’s finding that laches precluded a disgorgement award:

Rolex Watch USA, Inc. v Beckertime, LLC affirmed a finding of infringement, while also affirming the trial court’s finding that laches precluded a disgorgement award:

The district court concluded that at a minimum, Rolex’s agent “should have known about BeckerTime in 2010, ten years prior to the filing of the lawsuit, and no later than 2013 when [a Rolex employee] wrote that BeckerTime watches were junk.” … On appeal, Rolex offers no justification for the delay, instead arguing that BeckerTime failed to show prejudice. But the record supports that the ten years of permitted sales enabled BeckerTime to build up a successful business that it would not otherwise have invested in absent Rolex’s delay in filing suit. This is clear prejudice.

No. 22-10866 (Jan. 26, 2024).

After a massive computer failure, Southwest sued one of its cyber risk insures about five categories of damages (vouchers, frequent-flier miles, etc. used to mitigate the effects of the outage). The district court ruled against Southwest, describing the losses as arising from “purely discretionary” decisions.

After a massive computer failure, Southwest sued one of its cyber risk insures about five categories of damages (vouchers, frequent-flier miles, etc. used to mitigate the effects of the outage). The district court ruled against Southwest, describing the losses as arising from “purely discretionary” decisions.

The Fifth Circuit reversed. Acknowledging that the policy covered “all Loss … that in Insured incurs … solely as a result of a System Failure,” the Court reasoned:

Here, Liberty argues that the system failure cannot be the sole cause of Southwest’s claimed costs because the “independent” and “more direct” cause of those losses was Southwest’s decision to incur them. But those decisions can only be independent, sole causes of the costs if they were the precipitating causes of the costs. The decisions, like the infection in Wright or the medical complications in Wells, were not precipitating causes that competed with the system failure, but links in a causal chain that led back to the system failure.

Accordingly, the Court reversed and remanded. Southwest Airlines Co. v. Liberty Ins. Underwriters, Inc., No. 22-10942 (Jan. 16, 2024). The Court noted that “[t]he parties concede that there are no cases directly on point in the context of business interruption insurance.”

A challenge to the sale of a preference claim was rejected by the Fifth Circuit in Briar Capital v. Remmert: “[P]reference actions may be sold pursuant to 11 U.S.C. § 363(b)(1) because they are property of the estate under 11 U.S.C. §§ 541(a)(1) and (7). ” No. 22-20536 (Jan. 22, 2024).

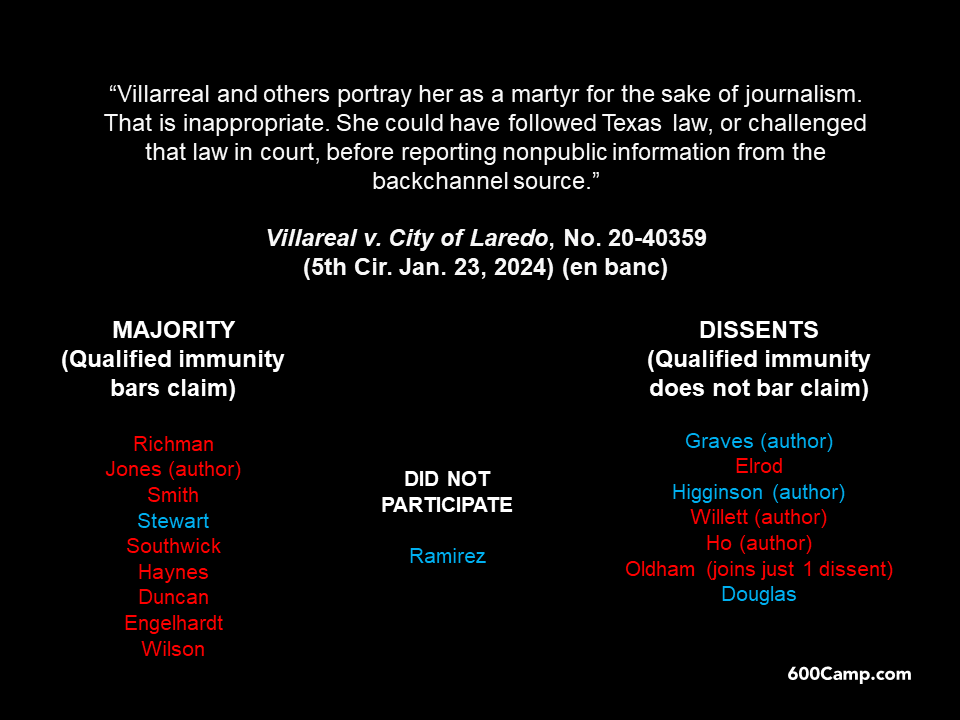

By a 9-7 margin, the full Fifth Circuit held that qualified immunity barred the wrongful-arrest claims of a Laredo “citizen-journalist.” Villarreal v. City of Laredo, No. 20-40359 (Jan. 23, 2024). The breakdown of votes appears below:

To the right appears William Humphrey, who like William Marbury, is known to history as the subject matter of a famous opinion. President Roosevelt’s efforts to remove Humphrey from the Federal Trade Commission led to the 1935 Supreme Court case of Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, about constitutional limits on the structure of administrative agencies. (Humphrey died during the litigation so his executor continued with the matter). In Consumers’ Research v. CPSC, the Fifth Circuit summarized the current state of the issue addressed by Humphrey’s Executor as follows:

To the right appears William Humphrey, who like William Marbury, is known to history as the subject matter of a famous opinion. President Roosevelt’s efforts to remove Humphrey from the Federal Trade Commission led to the 1935 Supreme Court case of Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, about constitutional limits on the structure of administrative agencies. (Humphrey died during the litigation so his executor continued with the matter). In Consumers’ Research v. CPSC, the Fifth Circuit summarized the current state of the issue addressed by Humphrey’s Executor as follows:

The Humphrey’s exception traditionally “has applied only to multimember bodies of experts.” Sitting en banc, we recently described the exception like this: Congress’s decision “limiting the President to ‘for cause’ removal is not sufficient to trigger a separation-of-powers violation.” Instead, for-cause removal creates a separation-of-powers problem only if it “combine[s]” with “other independence-promoting mechanisms” that “work[] together” to “excessively insulate” an independent agency from presidential control.

The plaintiffs in this case argue that the Supreme Court recently upended this framework in Seila Law. In their view, that 2020 decision held that for-cause removal always creates a separation-of-powers violation—at least if the agency at issue exercises substantial executive power (which nearly all agencies do). This is so, the plaintiffs argue, even if for-cause removal is the only structural feature insulating an agency from total presidential control. We do not read Seila Law so broadly. On the contrary, and as in Free Enterprise Fund, the Supreme Court in Seila Law left the Humphrey’s Executor exception “in place.”

No. 22-40328 (Jan. 17, 2024) (citations and footnote omitted).

After carefully reviewing what arguments were properly before it, the Fifth Circuit went on to hold in Shambaugh & Son, LP v. Steadfast Ins. Co. that the plaintiff had not established jurisdiction over an out-of-state insurer: “Steadfast could not have reasonably anticipated being haled into court in Texas simply because Shambaugh’s records were kept in an office (in Austin) maintained by a division (Northstar) of a subsidiary (Shambaugh).” No. 23-50004 (Jan. 18, 2024). The Court noted the insurer’s involvement with other Texas litigation but found those contacts irrelevant and inadequate to establishe jurisdiction.

After carefully reviewing what arguments were properly before it, the Fifth Circuit went on to hold in Shambaugh & Son, LP v. Steadfast Ins. Co. that the plaintiff had not established jurisdiction over an out-of-state insurer: “Steadfast could not have reasonably anticipated being haled into court in Texas simply because Shambaugh’s records were kept in an office (in Austin) maintained by a division (Northstar) of a subsidiary (Shambaugh).” No. 23-50004 (Jan. 18, 2024). The Court noted the insurer’s involvement with other Texas litigation but found those contacts irrelevant and inadequate to establishe jurisdiction.

Shambaugh & Son, LP v. Steadfast Ins. Co. presents a dispute about personal jurisdiction in an insurance-coverage case. The Fifth Circuit began by identifying the arguments properly before it, noting the distinction between waiver and forfeiture:

Shambaugh & Son, LP v. Steadfast Ins. Co. presents a dispute about personal jurisdiction in an insurance-coverage case. The Fifth Circuit began by identifying the arguments properly before it, noting the distinction between waiver and forfeiture:

“The terms waiver and forfeiture—though often used interchangeably by jurists and litigants—are not synonymous.” “Whereas forfeiture is the failure to make the timely assertion of a right, waiver is the ‘intentional relinquishment or abandonment of a known right.’”

Applying those standards, the Court observed, inter alia:

- “… if complaint allegations alone prevented subsequent forfeiture, then

it is difficult to imagine when any claim or argument could ever be forfeited”; - “… if including a claim in a complaint fails to preserve that claim … then a fortiori attaching an exhibit to a pleading does not insulate arguments derived from that exhibit“;

- A statement about choice of law did not avoid forfeiture when that “statement is nested within a broader discussion about forum shopping”;

- An argument about a specific statute was forfeited, and was not saved by a broader discussion about minimum contacts, when the lower-court briefing did not cite that statute and the statutory argument “is narrower and conceptually distinct from [appellant’s] other minimum contacts arguments.”

No. 23-50004 (Jan. 18, 2024).

In Book People, Inc. v. Wong, the Fifth Circuit reviewed the constitutionality of the Texas “READER” law, which “requires school book vendors who want to do business with Texas public schools to issue sexual-content ratings for all library materials they have ever sold (or will sell), flagging any materials deemed to be ‘sexually explicit’ or ‘sexually relevant’ based on the materials’ depictions of or references to sex.”

The Court held that the law violated the First Amendment, in that the ratings required by the law were not government speech, and fell within no exception to the rule against “compelled speech”:

- They did not come within the “government operations” exception because they “go[] beyond a mere disclosure of demographic or similar factual information.”

- Similarly, they were not a permissible commercial-speech regulation because “[b]alancing a myriad of factors that depend on community standards is anything but the mere disclosure of factual information.

No. 23-50668 (Jan. 17, 2024).

Please join the Dallas Bar Association Appellate Section at noon on Thursday, January 18, for a lunch presentation by me. I’ll be speaking on trends and cases to know from the past year in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and the Fifth District Court of Appeals. I’ve done a similar presentation around this time of year for a few years now.

Here’s my PowerPoint. This CLE will be in-person at the Arts District Mansion, 2101 Ross in downtown Dallas.

State of Louisiana v. U.S. Dep’t of Energy is an instructive analysis of basic administrative rulemaking concepts, in the unlikely setting of the regulation of washing machines and dishwashers. The substance will be discussed in future posts.

State of Louisiana v. U.S. Dep’t of Energy is an instructive analysis of basic administrative rulemaking concepts, in the unlikely setting of the regulation of washing machines and dishwashers. The substance will be discussed in future posts.

For today, in the “who knew?” department, the plaintiffs were several states, and their standing was based on the substantial purchases that those states made of those appliances. An affidavit quoted in the opinion, for example, describes the purchasing habits of the Montana Highway Patrol as to appliances for its bunkhouses. No. 22-60146 (Jan. 8, 2023).

The issue in Stewart v. Gruber was the exclusion of an untimely expert report; among other points made in affirming, the Fifth Circuit noted:

Plaintiffs fail to identify any precedent barring courts from considering whether the proponent of an untimely expert report declined an opportunity to cure such untimeliness by refusing to join a motion to continue that would have extended deadlines for both parties and therefore lessened any prejudice to the opposing party. Put another way, Plaintiffs were only willing to have extra time for them, not a similar extension for the Defendants who would need to, of course, have an expert that addressed the Plaintiffs’ expert. Such a notion on the part of the Plaintiffs was totally improper.

No. 23-30129 (Dec. 14, 2023, unpublished).

Illumina, Inc. v. FTC provides a comprehensive review of every aspect of an FTC antitrust decision about a merger:

Illumina, Inc. v. FTC provides a comprehensive review of every aspect of an FTC antitrust decision about a merger:

To sum up, Illumina’s constitutional challenges to the FTC’s authority are foreclosed by binding Supreme Court precedent, and substantial evidence supported the Commission’s conclusions that (1) the relevant market is the market for the research, development, and commercialization of MCED tests in the United States; (2) Complaint Counsel carried its initial burden of showing that the Illumina-Grail merger is likely to substantially lessen competition in that market under either the ability-and-incentive test or looking to the Brown Shoe factors; and (3) Illumina had not identified cognizable efficiencies to rebut the anticompetitive effects of the merger. However, in considering the Open Offer, the Commission used a standard that was incompatible with the plain language of the Clayton Act.

No. 23-60167 (Dec. 15, 2023). The “Open Offer” issue involved a dispute about precisely where an agreement, entered to stave off competition-based challenges to this merger, should be considered in the context of the relevant burdens of proof.

The concurrent causation doctrine precluded recovery under an insurance policy for alleged hurricane damage in Shree Rama, LLC v. Mt. Hawley Ins. Co.:

The concurrent causation doctrine precluded recovery under an insurance policy for alleged hurricane damage in Shree Rama, LLC v. Mt. Hawley Ins. Co.:

Shree Rama did not carry its burden under the concurrent causation doctrine. The policy issued by Mt. Hawley explicitly covers damage from wind and explicitly excludes damage from wear and tear. Viewing the facts in the light most favorable to Shree Rama, it is possible that some damage to the hotel roof came from Hurricane Hanna and some from wear and tear. But the concurrent causation doctrine requires Shree Rama to provide the jury with “a reasonable basis” for allocating the damage between wind and wear and tear. . Shree Rama provided no reasonable basis. To the contrary, Shree Rama admitted at the district court level that its causation expert “could not definitively attribute [specific damages to the roof] to Hurricane Hanna when deposed.” Without a basis for allocating damages between covered and non- covered causes, Mt. Hawley was entitled to summary judgment.

No. 23-40123 (Dec. 14, 2023) (citations omitted).

Smith v. Edwards examined whether a preliminary injunction should be vacated when the dispute became moot on appeal:

Smith v. Edwards examined whether a preliminary injunction should be vacated when the dispute became moot on appeal:

“[H]istorically, the established rule was to vacate the judgment if the case became moot on appeal.” However, in U.S. Bancorp Mortgage Co. v. Bonner Mall Partnership, “[t]he Supreme Court made clear and emphasized that vacatur is an ‘extraordinary’ and equitable remedy . . . to be determined on a case-by-case basis.” One principal consideration “is whether the party seeking relief from the judgment . . . caused the mootness by voluntary action.” “Thus, for example, ‘vacatur must be granted where mootness results from the unilateral action of the party who prevailed in the [district] court.’”

The equitable principles espoused in U.S. Bancorp and recognized by Staley apply in this case. Though Defendants complied with the preliminary injunction by removing the youths from BCCY-WF, they did not cause mootness by voluntary action. And though the injunction automatically expired under the PLRA, Plaintiffs could have sought an extension to extend its duration. . Having been “frustrated by the vagaries of circumstance, [Defendants] ought not in fairness be forced to acquiesce in the judgment.

No. 23-30634 (Dec. 19, 2023).

Start the New Year out right with “Get the Last Word in an Effective Reply Brief,” which I recently co-wrote for the Bar Association of the Fifth Federal Circuit with my skillful colleague Campbell Sode – available here along with many other valuable practice pointers by members of that great bar association.

Reiterating a recent holding in a near-identical lawsuit, in Bourque v. State Farm the Fifth Circuit rejected the certification of a class of insureds who were dissatisfied with the amount paid by State Farm for their wrecked cars:

Reiterating a recent holding in a near-identical lawsuit, in Bourque v. State Farm the Fifth Circuit rejected the certification of a class of insureds who were dissatisfied with the amount paid by State Farm for their wrecked cars:

Plaintiffs contended that they had met this standard because any class member who was paid less than the [National Automobile Dealers’ Association] value of their vehicle necessarily received less than [Actual Cash Value] and therefore suffered an injury. But we rejected that premise, explaining that NADA value was just one of many statutorily acceptable methods for calculating ACV, and therefore pinning ACV to NADA value constituted an impermissibly arbitrary choice of a liability model.

No. 22-30126 (Dec. 22, 2023).