The plaintiffs have responded to the United States’ motion for a stay during the pendency of Texas v. United States, No. 15-40238, so that matter is now in the hands of the Court.

Pursuant to section 965 of the Internal Revenue Code, BMC Software repatriated to the United States several hundred million dollars of income earned by a foreign subsidiary. It earned a substantial tax deduction for the year, as this provision is intended to incentivise the fresh investment of foreign cash into the U.S. by companies with international operations. BMC Software v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, No. 13-60684 (March 13, 2015). Some time later, BMC settled a dispute about the tax treatment of royalties paid to it by the same subsidiary. The IRS then took the position that BMC’s accounting for that dispute amounted to a loan, which would lead to the disallowal of some of the section 965 deduction (loaning money to a subsidiary who then returns it to the US would not be fresh investment). The Fifth Circuit rejected that position and reversed the Tax Court, finding no support for it in either the statute or the settlement document. Because the accounts receivable created as a result of the settlement were not created until after the applicable tax year, the statutory exception for loaned funds could not apply.

At issue in North Cypress Medical Center Operating Co. v. Cigna Healthcare was a basic aspect of the structure of a “preferred provider” insurance program. Under the many policies at issue, “in-network” providers receive more reimbursement than “out-of-network” ones, as an incentive to seek treatment in-network. With respect to the portion of the bill as to which patients had responsibility, certain providers provided “prompt pay” discounts. Insurers disputed whether they were then still responsible for the entire billed amount, or should have their responsibility reduced by a corresponding discount. The Fifth Circuit found that the patients, and thus the providers to whom they assigned their claims, had standing to litigate about this situation (reversing a district court ruling to the contrary). It also found that ERISA preempted state law claims about these issues, that limitations applied (without tolling) to compulsory counterclaims by insurers that sought affirmative relief rather than recoupment, and affirmed the dismissal of RICO claims by the provider. The litigation seems likely to continue, and to produce more issues about complicated and significant ERISA and procedural points. No. 12-20695 (March 10, 2015).

Allstate did not request a jury trial in its original complaint, but did in response to the defendant’s answer and counterclaim (which also included a jury demand, and which Allstate was entitled to rely upon). After a summary judgment ruling, Allstate made a limited jury waiver on the remaining issue of damages. The district court then vacated its summary judgment ruling and held a bench trial on all issues in the case — liability and damages.

Allstate did not request a jury trial in its original complaint, but did in response to the defendant’s answer and counterclaim (which also included a jury demand, and which Allstate was entitled to rely upon). After a summary judgment ruling, Allstate made a limited jury waiver on the remaining issue of damages. The district court then vacated its summary judgment ruling and held a bench trial on all issues in the case — liability and damages.

The Fifth Circuit found that, “[a]lthough deference is generally accorded to a trial judge’s interpretation of a pretrial order,” this was “[a]t the very least . . a ‘doubtful situation'” that did not support the finding of “a knowing and voluntary relinquishment of the right” to jury trial pursuant to the Seventh Amendment. The Court also found harm because Allstate’s case could survive a JNOV motion, noting that “the district court relied heavily on its weighing of the credibility of the witness’s testimony at trial” in its fact finding. Accordingly, the Court reversed and remanded for jury trial. Allstate Ins. Co. v. Community Health Center, Inc., No. 14-30506 (March 16, 2015, unpublished).

I am speaking to the Appellate Section of the Dallas Bar Association, at the Belo Mansion in downtown Dallas, at noon on Thursday March 19, with a Fifth Circuit update. The official title is “Horses, Whooping Cranes, and Eagle Feathers: the Fifth Circuit in 2014.” Here is a copy of the PowerPoint for the presentation.

Jefferson sued Delgado Community College, alleging that it was “an agency or instrumentality of the government of the State of Louisiana.” The Louisiana Attorney General appeared for the State, argued that she had not correctly named the State in the case, and suggested how to properly serve the college. Jefferson v. Delgado Community College, No. 14-30379 (March 12, 2015, unpublished). The district court denied the AG’s motion to dismiss, pointing to what the pleading said. The AG sought appellate review and the Fifth Circuit found it had no jurisdiction. The ruling was not appealable as a collateral order: “For example, personal jurisdiction implicates a defendant’s due process rights, but a defendant may not appeal the denial of a motion to dismiss based on lack of personal jurisdiction under the collateral order rule.” The Court also denied mandamus relief, noting that the district court’s ruling was not clearly erroneous given the language of the pleading, and suggesting that the parties may wish to consider the AG’s suggestion about proper service for future proceedings in the case.

Breaux sued ASC Industries for age discrimination, but died before the case resolved. Her attorney, Oglesby, filed a “suggestion of death” pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 25. ASC then obtained dismissal when the 90-day period set by that rule passed with no substitution. Breaux’s estate then sought reinstatement, pointing out that the estate representative had not been personally served pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 4 (Rule 25 provides that: “A motion to substitute, together with a notice of hearing, must be served on the parties as provided in Rule 5 and on nonparties as provided in Rule 4. A statement noting death must be served in the same manner.”) ASC countered that Oglesby also represented the estate. The Fifth Circuit sided with Breaux’s estate, finding that a personal representative is a nonparty under Rule 25, noting that is the majority position among Circuits, and distinguishing other cases that reached arguably inconsistent conclusions. Sampson v. ASC Industries, 14-10085 (March 13, 2015, unpublished).

After initially holding that the borrowers’ complaint survived a Twombly challenge as to whether the “grossly inadequate sales price” element of a wrongful foreclosure claim had been properly pleaded, the Fifth Circuit reversed field and issued a revised opinion that affirms dismissal: “We agree with the district court that Plaintiffs’ wrongful foreclosure claim should be dismissed, but for a different reason—Plaintiff’s abandoned the claim on appeal. In challenging the district court’s dismissal, Plaintiffs did not argue that their wrongful foreclosure claim should survive because they adequately pleaded a grossly inadequate sales price. They only argued that the claim should survive because they need not plead that element at all. However, our precedent requires this element in all but a specific category of cases that does not include the instant case.” Guajardo v. JP Morgan Chase, No. 13-51025 (March 10, 2015).

Allen Stanford spent close to $6 million advertising his investment firm on the Golf Channel. After his empire collapsed, the receiver sued the Golf Channel under the Texas fraudulent transfer statute. The Channel successfully defended in the district court on the ground that it gave reasonably equivalent value. Janvey v. The Golf Channel, No. 13-11305 (March 11, 2015). Unfortunately for the Channel, because the receiver proved Stanford was running a Ponzi scheme, the question was whether it gave value from the perspective of the creditors, not whether it provided quality advertising from the perspective of Stanford’s business operation. “Golf Channel argues that its advertising services did not further the Stanford Ponzi scheme and that the $5.9 million reasonably represents the market value of those services. . . . TUFTA makes no distinction between different types of services or different types of transferees, but requires us to look at the value of any services from the creditors’ perspective. We have no authority to create an exception for ‘trade creditors.'” Accordingly, the Fifth Circuit reversed.

Allen Stanford spent close to $6 million advertising his investment firm on the Golf Channel. After his empire collapsed, the receiver sued the Golf Channel under the Texas fraudulent transfer statute. The Channel successfully defended in the district court on the ground that it gave reasonably equivalent value. Janvey v. The Golf Channel, No. 13-11305 (March 11, 2015). Unfortunately for the Channel, because the receiver proved Stanford was running a Ponzi scheme, the question was whether it gave value from the perspective of the creditors, not whether it provided quality advertising from the perspective of Stanford’s business operation. “Golf Channel argues that its advertising services did not further the Stanford Ponzi scheme and that the $5.9 million reasonably represents the market value of those services. . . . TUFTA makes no distinction between different types of services or different types of transferees, but requires us to look at the value of any services from the creditors’ perspective. We have no authority to create an exception for ‘trade creditors.'” Accordingly, the Fifth Circuit reversed.

With a stay motion still pending in the district court, the United States has asked the Fifth Circuit for an emergency stay of the recent ruling that enjoins President Obama’s immigration program. No. 15-40238. A short clerk’s order, which does not reveal the identity or involvement of any judge “behind the curtain,” has set a response date of March 23. Law360 has written a good article with more detail about the current status in the district court.

In November, a Fifth Circuit panel affirmed the NLRB’s $30,000 award in a retaliation case based on the employer’s handling of a whistleblower. Halliburton Co. v. Administratve Review Board, U.S. Dep’t of Labor, No. 13-60323. The full court has now denied the petition for en banc review, by the close margin of 7 judges for review and 8 against. A 3-judge dissent criticizes the “ad hoc nature” of the panel opinion and warns that it will lead to confusion about what specific conduct can amount to a materially adverse employment action in the context of a retaliation claim.

Fed. R. Civ. P. 60, titled “Grounds for Relief from a Final Judgment, Order, or Proceeding,” is generally invoked to vacate a judgment because of alleged misconduct, mistake, newly-discovered evidence, or other equitable reasons. Clause (5) of that rule also allows relief if “the judgment has been satisfied, released, or discharged; it is based on an earlier judgment that has been reversed or vacated; or applying it prospectively is no longer equitable.” That provision — and specifically, its rarely-litigated first clause — was at issue in Frew v. Janek, in which the Texas Health and Human Services Commission argued that it had fully performed under a consent decree related to the operation of a Medicaid program. No. 14-40048 (March 5, 2015). Construing the decree “according to ‘general principles of contract interpretation,'” and declining to apply the law of the case doctrine to the interpretation of the decree by the judge who entered the order, the Fifth Circuit found no error in the district court’s ruling that the defendants had complied with the order and performed fully.

Fed. R. Civ. P. 60, titled “Grounds for Relief from a Final Judgment, Order, or Proceeding,” is generally invoked to vacate a judgment because of alleged misconduct, mistake, newly-discovered evidence, or other equitable reasons. Clause (5) of that rule also allows relief if “the judgment has been satisfied, released, or discharged; it is based on an earlier judgment that has been reversed or vacated; or applying it prospectively is no longer equitable.” That provision — and specifically, its rarely-litigated first clause — was at issue in Frew v. Janek, in which the Texas Health and Human Services Commission argued that it had fully performed under a consent decree related to the operation of a Medicaid program. No. 14-40048 (March 5, 2015). Construing the decree “according to ‘general principles of contract interpretation,'” and declining to apply the law of the case doctrine to the interpretation of the decree by the judge who entered the order, the Fifth Circuit found no error in the district court’s ruling that the defendants had complied with the order and performed fully.

I just wrote an article in the most recent Appellate Advocate – the publication of the Texas State Bar Appellate Section – about the key recent cases from the Fifth Circuit about jury charge error. I hope you enjoy it and find it useful in your practice!

Richardson alleged that he was terminated, in violation of Louisiana’s whistleblower statute, for revealing fraudulent time records and overbilling. The district court granted summary judgment and the Fifth Circuit reversed. Richardson v. Axion Logistics, No. 14-30306 (revised March 23, 2015). Applying the Twombly “plausibility” standard, the Court found adequate pleading about his employer’s knowledge of the alleged misconduct, as well as the timeline of events leading up to his termination. The pleading itself is available for review here; the specific paragraphs identified by the Court as to the employer’s knowledge are highlighted in yellow, and those identified about his termination in orange.

The L/B Nicole Eymard (right) became stuck while servicing a well in the Gulf of Mexico. The owner of the boat sued the contractor that hired the boat, in addition to the well owner, and both were found liable for charter fees while the vessel was unable to move. The well owner obtained indemnity from the contractor because the contractor had agreed to indemnify it for

The L/B Nicole Eymard (right) became stuck while servicing a well in the Gulf of Mexico. The owner of the boat sued the contractor that hired the boat, in addition to the well owner, and both were found liable for charter fees while the vessel was unable to move. The well owner obtained indemnity from the contractor because the contractor had agreed to indemnify it for  claims “based upon personal injury or death or property damage or loss.” Unpaid charter fees are a “loss” within the meaning of that language, even without proof of damage to property. Offshore Marine Contractors, LLC v. Palm Energy Offshore, LLC, No. 14-30059 (March 2, 2015).

claims “based upon personal injury or death or property damage or loss.” Unpaid charter fees are a “loss” within the meaning of that language, even without proof of damage to property. Offshore Marine Contractors, LLC v. Palm Energy Offshore, LLC, No. 14-30059 (March 2, 2015).

An insurer settled with its insured; the settlement “did not contain an admission of liability under the Policy and both parties dispute whether the Policy covered the four claims at issue.” Accordingly, the insured had no claim under the Texas Prompt Payment Act for an alleged breach of the settlement. Tremago, L.P. v. Euler-Hermes American Credit Indemnity Co., No. 13-41179 (Feb. 25, 2015, unpublished). The Court also found that a trio of statements such as “[Plainitff] has not alleged, let alone proffered any evidence of any act on [Defendant’s] part that fairly can be characterized as ‘so extreme’ that it would cause ‘injury independent of the policy claim’ was sufficient to place the plaintiff on notice that its extra-contractual claims were within the scope of the defendant’s summary judgment motion.

A design firm proved at trial that Hallmark Design Homes built hundreds of houses such as the one on the right, using its copyrighted plans without permission. Hallmark filed for bankruptcy; the remaining issue was whether the claim was “advertising injury” under Mid-Continent’s various liability policies. Mid-Continent Casualty Co. v. Kipp Flores Architects, LLC, No. 14-50649 (Feb. 26, 2015, unpublished).

A design firm proved at trial that Hallmark Design Homes built hundreds of houses such as the one on the right, using its copyrighted plans without permission. Hallmark filed for bankruptcy; the remaining issue was whether the claim was “advertising injury” under Mid-Continent’s various liability policies. Mid-Continent Casualty Co. v. Kipp Flores Architects, LLC, No. 14-50649 (Feb. 26, 2015, unpublished).

The Fifth Circuit affirmed judgment for the insured. After reminding that additional evidence can be offered in a coverage dispute about matters addressed in a prior lawsuit, the Court held: “[I]t is undisputed that Hallmark’s primary means of marketing its construction business was through the use of the homes themselves, both through model homes and yard signs on the property of infringing homes it had built, all of which were marketed to the general public . . . .” Because the homes themselves were “advertisements,” Mid-Continent’s policies covered the prior judgment.

(This post’s title comes from an exchange between Falstaff and Mistress Ford in The Merry Wives of Windsor.)

As part of a sale transaction, the board of “Gold Kist” (more widely known as Pilgrim’s Pride), decided to abandon certain securities for no consideration. For tax purposes, the company then reported a $98.6 million ordinary loss. Pilgrim’s Pride Corp. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, No. 14-60295 (Feb. 25, 2015). The IRS contended that this was a capital loss, rather than an ordinary loss, creating a tax deficiency of close to $30 million. The Court agreed with the company, finding: “By its plain terms, [26 U.S.C.] § 1234A(1) applies to the termination of rights or obligations with respect to capital assets (e.g. derivative or contractual rights to buy or sell capital assets). It does not apply to the termination of ownership of the capital asset itself.” In rejecting a contrary view of the statute, Judge Elrod gives a powerful summary of several canons of construction: “We disagree. Congress does not legislate in logic puzzles . . . “

As part of a sale transaction, the board of “Gold Kist” (more widely known as Pilgrim’s Pride), decided to abandon certain securities for no consideration. For tax purposes, the company then reported a $98.6 million ordinary loss. Pilgrim’s Pride Corp. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, No. 14-60295 (Feb. 25, 2015). The IRS contended that this was a capital loss, rather than an ordinary loss, creating a tax deficiency of close to $30 million. The Court agreed with the company, finding: “By its plain terms, [26 U.S.C.] § 1234A(1) applies to the termination of rights or obligations with respect to capital assets (e.g. derivative or contractual rights to buy or sell capital assets). It does not apply to the termination of ownership of the capital asset itself.” In rejecting a contrary view of the statute, Judge Elrod gives a powerful summary of several canons of construction: “We disagree. Congress does not legislate in logic puzzles . . . “

In 2012, the Fifth Circuit remanded a False Claims Act case with the direction: “The district court should determine whether the public disclosures identified in the motion for summary judgment reveal either (i) that Shell was deducting gathering expenses prohibited by program regulations, or (ii) that this type of fraud was so pervasive in the industry that the company’s scheme, as alleged, would have been easily identified.” Little v. Shell Exploration, 690 F.3d 282 (5th Cir. 2012). On remand, the district court again granted summary judgment for the defense, and a displeased Fifth Circuit reversed. Little v. Shell Exploration II, No. 14-20156 (Feb. 23, 2015, unpublished).

The Court found: “Not only did the district court fail to follow these explicit instructions, but the analysis set out in its short opinion is so broad, conclusory, and unsupported by the summary judgment record that we are compelled to conclude it did not comply with our instructions.” On the merits, the Court held that “the district court erred with respect to every category of supposed public disclosures.” The Court went on to order reassignment to a different district judge on remand, concluding: ” Facing a lengthy and detailed summary judgment record, the district judge issued a five-page opinion with few

citations to either record evidence or relevant legal authority—not surprising given that neither the summary judgment evidence nor the law support the conclusions he reached.”

The Fifth Circuit has now docketed the federal government’s appeal of the recent ruling that enjoins President Obama’s immigration program; meanwhile, in the district court, the plaintiffs’ response to the federal government’s motion to stay pending appeal is due by March 2.

Pennzoil has several well-known trademarks for its motor oil products. It sued Miller Oil, which operates a quick-stop oil change facility in Houston, for infringing those marks. Miller defended on the ground that after its original contract with Pennzoil lapsed in 2003, Pennzoil’s dealings with Miller amounted to an acquiescence in Miller’s use of the marks. The district court agreed but the Fifth Circuit reversed. Pennzoil-Quaker State Co. v. Miller Oil & Gas Operations, No. 13-20558 (Feb. 23, 2015).

Pennzoil has several well-known trademarks for its motor oil products. It sued Miller Oil, which operates a quick-stop oil change facility in Houston, for infringing those marks. Miller defended on the ground that after its original contract with Pennzoil lapsed in 2003, Pennzoil’s dealings with Miller amounted to an acquiescence in Miller’s use of the marks. The district court agreed but the Fifth Circuit reversed. Pennzoil-Quaker State Co. v. Miller Oil & Gas Operations, No. 13-20558 (Feb. 23, 2015).

The Court thoroughly reviewed its own, and other Circuits’, approaches to the elements of the acquiescence defense, as well as the relationship of that defense to laches. The Court concluded that an element of the defense was undue prejudice to the defendant from the plaintiff’s conduct, which usually involves “some form of ‘business building.'” Here, the defendant’s expenses associated with removing Pennzoil’s marks did not  satisfy that requirement, because they would not be related to business expansion. While the defendant’s claim about a “loss of identity” from removing Pennzoil’s marks could qualify, on this record: “Miller Oil does not proffer evidence of, for example, changes in its customer base, higher profits, or new business opportunities it was able to exploit because of the re-brand.” Accordingly, Miller Oil did not meet its burden of proof.

satisfy that requirement, because they would not be related to business expansion. While the defendant’s claim about a “loss of identity” from removing Pennzoil’s marks could qualify, on this record: “Miller Oil does not proffer evidence of, for example, changes in its customer base, higher profits, or new business opportunities it was able to exploit because of the re-brand.” Accordingly, Miller Oil did not meet its burden of proof.

In Frey v. First National Bank Southwest, No. 13-10375 (Feb. 20, 2015), an appeal that was stayed in deference to the ruling in Mabary v. Home Town Bank, N.A., 771 F.3d 820 (5th Cir. 2014), the Fifth Circuit again affirmed the certification of a class related to notice requirements about ATM fees: “The primary questions with regard to First National’s liability are whether and when First National failed to provide the on-machine fee notice in violation of the EFTA’s requirements during the class period; if so, the appropriate amount of statutory damages; and whether the bank can avail itself of either of the two statutory defenses to liability. The answers to these questions will affect all class member’s claims.”

In Frey v. First National Bank Southwest, No. 13-10375 (Feb. 20, 2015), an appeal that was stayed in deference to the ruling in Mabary v. Home Town Bank, N.A., 771 F.3d 820 (5th Cir. 2014), the Fifth Circuit again affirmed the certification of a class related to notice requirements about ATM fees: “The primary questions with regard to First National’s liability are whether and when First National failed to provide the on-machine fee notice in violation of the EFTA’s requirements during the class period; if so, the appropriate amount of statutory damages; and whether the bank can avail itself of either of the two statutory defenses to liability. The answers to these questions will affect all class member’s claims.”

The Fifth Circuit has withdrawn its high-profile opinion (as to damages) in Forte v. Wal-Mart Stores, which found that civil penalties were not available absent actual damages in a suit under a Texas statutory cause of action about optometry. The controlling issues have now been certified to the Texas Supreme Court.

Superior MRI Services sued for tortious interference with contract; the defendant argued that Superior lacked standing because it never acquired rights under the relevant contracts, and the Fifth Circuit agreed. Superior MRI Services, Inc. v. Alliance Imaging, Inc., No. 14-60087 (Feb. 18, 2015). The record showed that P&L Imaging, a bankruptcy debtor, listed “MRI service agreements” on its schedule of assignments to Superior, with an assignment date of October 1, 2011. Superior, however, did not exist as a legal entity until November 28, 2011. No evidence showed that Superior ratified the contract after its formation, and the Court was unwilling to accept Mississippi’s approval of Superior as a vendor as evidence of a ratification. The Court distinguished the recent case of Lexmark, Int’l v. Static Control Components, 134 S. Ct. 1377 (2014), as relating to another aspect of the standing requirement.

Superior MRI Services sued for tortious interference with contract; the defendant argued that Superior lacked standing because it never acquired rights under the relevant contracts, and the Fifth Circuit agreed. Superior MRI Services, Inc. v. Alliance Imaging, Inc., No. 14-60087 (Feb. 18, 2015). The record showed that P&L Imaging, a bankruptcy debtor, listed “MRI service agreements” on its schedule of assignments to Superior, with an assignment date of October 1, 2011. Superior, however, did not exist as a legal entity until November 28, 2011. No evidence showed that Superior ratified the contract after its formation, and the Court was unwilling to accept Mississippi’s approval of Superior as a vendor as evidence of a ratification. The Court distinguished the recent case of Lexmark, Int’l v. Static Control Components, 134 S. Ct. 1377 (2014), as relating to another aspect of the standing requirement.

Pearl Seas sued Lloyd’s Register North America (“LRNA”) for inadequate performance in certifying a cruise ship (the “Pearl Mist,” seen to the right.) LRNA moved to dismiss on the grounds of forum non conveniens in favor of England, citing a forum selection clause contained in its rules. The district court denied the motion without explanation and the Fifth Circuit reversed in a 2-1 panel opinion. In re Lloyd’s Register North America, Inc.. No. 14-20554 (Feb. 24, 2015), re-released after initial publication as a per curiam opinion on February 18.

Pearl Seas sued Lloyd’s Register North America (“LRNA”) for inadequate performance in certifying a cruise ship (the “Pearl Mist,” seen to the right.) LRNA moved to dismiss on the grounds of forum non conveniens in favor of England, citing a forum selection clause contained in its rules. The district court denied the motion without explanation and the Fifth Circuit reversed in a 2-1 panel opinion. In re Lloyd’s Register North America, Inc.. No. 14-20554 (Feb. 24, 2015), re-released after initial publication as a per curiam opinion on February 18.

The Court held: (1) as in the case of In re: Volkswagen, 545 F.3d 304 (5th Cir. 2008) (en banc), which involved the denial of a motion to transfer venue, mandamus is appropriate in the context of forum non conveniens; (2) it is an abuse of discretion to “grant or deny a[n FNC] motion without written or oral explanation” as to the relevant factors; and (3) the plaintiff was plainly bound by LRNA’s rules under the doctrine of direct-benefit estoppel, since its claim “referenced duties that must be resolved by reference to the classification society’s rules.” (citing Hellenic Inv. Fund v. Det Norkse Veritas, 464 F.3d 514 (5th Cir. 2006)). (A panel reached a similar result in Vloeibare Pret Limited v. Lloyd’s Register North America, Inc., No. 14-20538 (April 16, 2015, unpublished).

A dissent by Judge Elrod argued that the majority’s analysis of direct-benefit estoppel expanded the Court’s prior holdings in two areas — the degree to which the claim incorporated the relevant rules, and the timing of when the plaintiff learns of the rules. The dissent also expressed concern that the substantive claim would not be recognized in England.

The point of division between the majority and dissent — whether an error is “clear” or not — resembles a similar split between the majority and dissent in the mandamus case of In re Radmax, 720 F.3d 285 (5th Cir. 2013), which granted the writ as to the erroneous denial of an “intra-district” motion to transfer venue. Interestingly, Judge Higginson was the dissenter in Radmax, and also dissented from the denial of en banc review of that panel opinion, while here he forms part of the two-judge majority that grants mandamus relief. Judge Smith, who was in the majority of the Radmax panel opinion, is the author of this opinion after its initial release as per curiam.

In the case of In re Deepwater Horizon, the Texas Supreme Court has answered the certified questions raised in a significant insurance case about BP’s coverage related to the Deepwater Horizon disaster. (No. 130670, Tex. Feb. 13, 2015.) The issue is whether BP was an additional insured under policies obtained by Transocean, the operator of the ill-fated rig. Applying Evanston Ins. Co. v. ATOFINA Petrochemicals, Inc., 256 S.W.3d 660 (Tex. 2008), the Court held that “it is possible for a named insured to purchase a greater amount of coverage for an additional insured than an underlying service contract requires,” and that “the scope of indemnity and insurance clauses in service contracts is not necessarily congruent.” From that foundation, the court concluded: “The Drilling Contract required Transocean to name BP as an additional insured only for the liability Transocean assumed under the contract. Accordingly, Transocean had separate duties to indemnify and insure BP for certain risk, but the scope of that risk for either indemnity or insurance purposes extends only to above-surface pollution.”

Monday evening, a district judge in South Texas enjoined President Obama’s immigration program; the full text of his opinion is available here. (The case has the remarkably awkward caption of “Texas v. United States.”) An appeal has not yet been docketed with the Fifth Circuit. As with the recent gay marriage arguments, the makeup of the panel will be critical to the resolution of this extremely important case. The Washington Post story is a good example of the media coverage of the ruling.

Fernando Ramirez died after a beating by security guards at a nightclub. His estate sued the guards and the business that owned the club, as well as subsequent owners, alleging a scheme to hide assets. This lawsuit led to an insurance coverage dispute between the subsequent owners and the CGL carrier at the time of the incident. Colony Ins. Co. v. Price, No. 14-10317 (Feb. 12, 2015, unpublished). The specific allegations against the later owners in the underlying suit are far from clear, and appear to be obscured by broad use of the term “Defendants.” Nevertheless, the district court and Fifth Circuit agreed that these parties were not covered as “employees” under the policy: “Most obviously, the Price Defendants fail to explain how MTP and TOM, a partnership and a limited liability company, can be employees at all, let alone employees who falsely imprisoned Ramirez on October 1, 2008, particularly given that the Petition alleges that they were not formed until December 31 of the following year.”

1. I am speaking at the Dallas Bar Appellate Section meeting on March 19 at the Belo Mansion, with an update on recent Fifth Circuit opinions of general interest.

2. This year’s Super Lawyers nomination deadline is Wednesday, February 18 (two days from now). Take a few minutes to support the publication and your colleagues; the nomination form is here.

The defendants in a wrongful foreclosure case removed and the district court dismissed the borrower’s claims on the pleadings. The Fifth Circuit reversed for jurisdictional reasons. Smith v. Bank of America, No. 14-50256 (revised March 20, 2015, unpublished).

As to diversity jurisdiction, which was based on improper joinder of several defendants, the Court reminded: “[W]hen confronted with an allegation of improper joinder, the court must determine whether the removing party has discharged its substantial burden before proceeding to analyze the merits of the action.”

‘Blanton sued for employment discrimination, and after trial, “[t]here is no question that Blanton was subjected to egregious verbal sexual and racial harassment by the general manager of the Pizza Hut store where he worked.” Blanton v. Newton Associates, Inc., No. 14-50087 (Feb. 10, 2015, unpublished). The issue on appeal was whether the employer had established “the Ellerth/Faragher affirmative defense”; essentially, that the employer acted reasonably to stop the harassment and the employee unreasonably failed to enlist the employer’s aid. The evidence showed a lack of training about the employer’s anti-discrimination policies, and that two low-level supervisors hesitated to report the harassment for fear of retaliation by the general manager, but that “[o]nce Blanton did complain to a manager with authority over the general manager, Pizza Hut completed an investigation and fired her within four days.” Accordingly, the verdict and resulting judgment for the employer was affirmed.

The issue in Lowman v. Jerry Whitaker Timber Contractors, LLC was whether certain timber companies had vicarious liability for allegedly unlawful logging activities, in DeSoto Parish, Louisiana, in violation of that state’s timber cutting statute. Evidence showed that the loggers sold timber to the mills and in return received a “scale ticket” — a sort of commercial paper that can be bought and sold and allows small loggers immediate access to sale proceeds — which featured a description of the wood. Plaintiffs offered an affidavit from a state investigator who described the defendants’ “prior schemes involving the theft of timber and the falsifying of scale tickets,” and opined that he saw “‘the same pattern’ of activity” here. The Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for the defendants, finding that the evidence showed no connection between the tickets he reviewed and the timber at issue, much less any “right of control or supervision” by the defendants over the loggers. No. 14-30787 (Feb. 10, 2015, unpublished).

The issue in Lowman v. Jerry Whitaker Timber Contractors, LLC was whether certain timber companies had vicarious liability for allegedly unlawful logging activities, in DeSoto Parish, Louisiana, in violation of that state’s timber cutting statute. Evidence showed that the loggers sold timber to the mills and in return received a “scale ticket” — a sort of commercial paper that can be bought and sold and allows small loggers immediate access to sale proceeds — which featured a description of the wood. Plaintiffs offered an affidavit from a state investigator who described the defendants’ “prior schemes involving the theft of timber and the falsifying of scale tickets,” and opined that he saw “‘the same pattern’ of activity” here. The Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for the defendants, finding that the evidence showed no connection between the tickets he reviewed and the timber at issue, much less any “right of control or supervision” by the defendants over the loggers. No. 14-30787 (Feb. 10, 2015, unpublished).

An attorney challenged sanctions and contempt orders on appeal; one of her major points was inability to pay. The Fifth Circuit reminded that inability to pay is a defense to a charge of civil contempt, as to which “[t]he alleged contemnor bears the burden of producing evidence of his inability to comply. Failure to do so waives further consideration of this issue, even in the face of an order that added $100/day for noncompliance. Garrett v. Coventry, No. 14-10525 (Feb. 6, 2015).

BNSF Railway Co. v. Alstom Transportation presented a challenge to an arbitration award, in a contract dispute about the maintenance of rail cars. No. 13-11274 (Feb. 5, 2015). The Fifth Circuit brushed aside a number of challenges to the arbitrator’s legal analysis, quoting the Seventh Circuit: “As we have said too many times to want to repeat again, the question for decision by a federal court asked to set aside an arbitration award . . . is not whether the arbitrator or arbitrators erred in interpreting the contract; it is not whether they clearly erred in interpreting the contract; it is not whether they grossly erred in interpreting the contract; it is whether they interpreted the contract.”

BNSF Railway Co. v. Alstom Transportation presented a challenge to an arbitration award, in a contract dispute about the maintenance of rail cars. No. 13-11274 (Feb. 5, 2015). The Fifth Circuit brushed aside a number of challenges to the arbitrator’s legal analysis, quoting the Seventh Circuit: “As we have said too many times to want to repeat again, the question for decision by a federal court asked to set aside an arbitration award . . . is not whether the arbitrator or arbitrators erred in interpreting the contract; it is not whether they clearly erred in interpreting the contract; it is not whether they grossly erred in interpreting the contract; it is whether they interpreted the contract.”

Also, on procedural grounds, the Court rejected a challenge to the propriety of having arbitrated “gateway questions” of arbitrability. The district court had partially vacated the arbitrator’s award, the appellant (successfully) challenged that ruling, and BNSF had considerable latitude to defend it. But the “gateway” argument that arbitration should never have occurred, and that the award should thus be vacated in full, could not be presented on appeal absent a cross-appeal because it “asks for an expansion of the judgment.”

Also, on procedural grounds, the Court rejected a challenge to the propriety of having arbitrated “gateway questions” of arbitrability. The district court had partially vacated the arbitrator’s award, the appellant (successfully) challenged that ruling, and BNSF had considerable latitude to defend it. But the “gateway” argument that arbitration should never have occurred, and that the award should thus be vacated in full, could not be presented on appeal absent a cross-appeal because it “asks for an expansion of the judgment.”

In the press of year-end business, I neglected to cover a notable mandamus opinion in 2014 from the Federal Circuit, In re Google, Inc, No. 2014-147, 2014 WL 5032336 (Oct. 9, 2014). Reminiscent of that Court’s opinion in In re Genentech, 566 F.3d 1338 (2009), and the Volkswagen/Radmax line of cases from the Fifth Circuit, In re: Google addresses the denial of a motion to transfer patent litigation from the Eastern District of Texas.

The district court focused on “each defendant mobile phone manufacturer’s ability to modify and customize” the relevant platform. The Federal Circuit disagreed and granted mandamus relief, emphasizing the “substantial similarity involving the infringement and invalidity issues in all the suits.” That Court also rejected an argument based on the first-filed rule, finding that on these facts, “the equities of the situation do not depend on this argument.” (quoting Kerotest Mfg. Co. v. C-O-Two Fire Equip Co., 342 U.S. 180, 186 n.6 (1952). Concluding with a review of the practical considerations listed by 1404(a), the Court noted that the product at issue was developed in the Northern District of California, and thus the “bulk of the relevant evidence” is there as well.

In an earlier opinion, the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment in favor of an insured, finding a fact issue as to whether late notice caused prejudice to the carrier. “Berkley I,” Berkley Regional Ins. Co. v. Philadelphia Indemnity Ins. Co., 690 F.3d 342 (5th Cir. 2012). After further proceedings, the district court granted summary judgment to the carrier and the Court affirmed. “Berkley II,” Berkley Regional Ins. Co. v. Philadelphia Indemnity Ins. Co., No. 13-51180 c/w No. 14-50099 (Jan. 27, 2015, unpublished). The key issue was whether notice to the broker sufficed to give notice the the carrier; the Court reasoned that even if the broker had a limited agency relationship with the carrier, notice of claims fell outside its scope: “Under the 2002 Agreement, Philadelphia expressly allowed [Agent] to act as an insurance broker and sell Philadelphia policies as Philadelphia’s representative, subject to Philadelphia’s approval. The 2002 Agreement is silent as to whether [Agent] had the ability to accept notice of claims on behalf of Philadelphia. Thus, [Agent] did not have express authority to accept notice of claims.” For the same reasons, an implied agency theory was also rejected.

The insurance coverage case of Mt. Hawley Ins. Co. v. Advance Products & Systems, Inc. illustrates the recurring differences of opinion between the Fifth Circuit and district courts about contract ambiguity. 14-30068 (Jan. 27, 2015, unpublished). When APS made a claim on its commercial property policy with Mt. Hawley, APS’s recovery was limited by a “coinsurance provision” that applies if it “has not insured the full value of its income.” The parties differed on whether “income” referred to projected or actual net income; the district court found ambiguity, and the Fifth Circuit reversed: “Although APS has a point—the language used in calculating the coinsurance penalty is imprecise—it does not render the contract ambiguous.” Based on the relationship between this provision and other parts of the policy, and the general purposes of coinsurance clauses, the Court reversed a summary judgment for the insured.

The insurance coverage case of Mt. Hawley Ins. Co. v. Advance Products & Systems, Inc. illustrates the recurring differences of opinion between the Fifth Circuit and district courts about contract ambiguity. 14-30068 (Jan. 27, 2015, unpublished). When APS made a claim on its commercial property policy with Mt. Hawley, APS’s recovery was limited by a “coinsurance provision” that applies if it “has not insured the full value of its income.” The parties differed on whether “income” referred to projected or actual net income; the district court found ambiguity, and the Fifth Circuit reversed: “Although APS has a point—the language used in calculating the coinsurance penalty is imprecise—it does not render the contract ambiguous.” Based on the relationship between this provision and other parts of the policy, and the general purposes of coinsurance clauses, the Court reversed a summary judgment for the insured.

Felder’s Collision Parts sells aftermarket parts for GM cars; it sued GM and several dealers in original equipment manufactured parts made by GM, alleging that they ran a pricing and rebate program (with the unfortunate name of “Bump the Competition”) that amounted to predatory pricing. The district court dismissed and the Fifth Circuit affirmed in Felder’s Collision Parts, Inc. v. All Star Advertising Agency, No. 14-30410 (Jan. 27, 2015).

Felder’s Collision Parts sells aftermarket parts for GM cars; it sued GM and several dealers in original equipment manufactured parts made by GM, alleging that they ran a pricing and rebate program (with the unfortunate name of “Bump the Competition”) that amounted to predatory pricing. The district court dismissed and the Fifth Circuit affirmed in Felder’s Collision Parts, Inc. v. All Star Advertising Agency, No. 14-30410 (Jan. 27, 2015).

Under the program, a dealer would offer a price significantly lower than the ordinary aftermarket part price. Felder’s argued the dealer was pricing beneath average variable cost — and thus engaging in predatory pricing — and offered an example of a dealer selling a part for $119 that it bought from GM for $135. The defendants pointed out that a key part of the program was a rebate to the dealer from GM based on sales, and including that rebate in the “cost” calculation turned the seeming $15 loss in this example into a 14% profit.

The Fifth Circuit agreed: “The price versus cost comparison focuses on whether the money flowing in for a particular transaction exceeds the money flowing out. The rebate undoubtedly affects that bottom line for All Star by guaranteeing that it makes a profit on any Bump the Competition sale. That undisputed fact resolves the case, as a ‘firm that is selling at a shortrun profit maximizing (or loss-minimizing) price is clearly not a predator.'” The Court acknowledged: “Felder’s no doubt is having a tougher time selling aftermarket equivalent parts for GM vehicles . . . But antitrust law welcomes those lower prices for consumers of collision parts so long as neither GM nor its dealers is selling parts at below-cost levels.” (Or, “parts is parts . . . “)

Ratliff Ready-Mix, a creditor of Barry Pledger’s construction business, argued that its claim was not dischargeable in Pledger’s bankrupcty because it arose from a violation of the Texas Construction Trust Fund Statute. Reviewing the case law about this statute and the defenses it provides, the Fifth Circuit affirmed judgment for the debtor. To overcome Pledger’s statutory affirmative defense, “Ratliff had to establish that the payments made by Pledger were not ‘actual expenses directly related to the construction.’ Specifically, Ratliff must show that (a) these were not payments made on the project or overhead, or (b) they were made for Pledger’s own uses rather than to benefit the health of his failing business.” Ratliff Ready-Mix v. Pledger, No. 14-50023 (Jan. 23, 2015, unpublished). Here, “[i]t would be hard to argue that paying taxes, repairing vehicles and equipment, and compensating employees could be categorized as anything other than maintaining the business.”

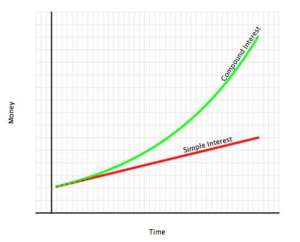

The note said: “So long as an Event of Default remains outstanding: (a) interest shall accrue at the Default Rate and, to the extent not paid when due, shall be added to the Principal Amount . . . .” The lender said this language meant that interest should be compounded, and the lower courts agreed — in the amount of almost $5 million. The borrower argued that this language only meant “that any unpaid interest will be added

The note said: “So long as an Event of Default remains outstanding: (a) interest shall accrue at the Default Rate and, to the extent not paid when due, shall be added to the Principal Amount . . . .” The lender said this language meant that interest should be compounded, and the lower courts agreed — in the amount of almost $5 million. The borrower argued that this language only meant “that any unpaid interest will be added

to the principal amount as the total debt due.” The Fifth Circuit disagreed, finding that this reading would impermissibly make the provision redundant “because it would operate only to label the accrued interest as money owed by [borrower] to [lender], and the interest was already owed. TCI Courtyard, Inc. v. Wells Fargo Bank, N.A., No. 14-10635 (Jan. 22, 2015, unpublished).

The district court dismissed a borrower’s breach of contract claim against a mortgage servicer because the borrower was in substantial arrears, and “as a general principle . . . an individual in breach cannot bring a cause of action for breach against another contracting party.” The Fifth Circuit reversed, finding that the borrower had alleged plausible claims that the servicer breached first; specially, that “the misapplication of [the borrrower’s] payments to an escrow account, resulting in default . . . constituted a material breach,” and that “Chase’s rejection of her mortgage payments, even if not a material breach, rendered performance impossible and that, as a result, any subsequent breach does not bar her claim.” Peters v. JP Morgan Chase, No. 13-50157 (Jan. 23, 2015, unpublished).

The district court dismissed a borrower’s breach of contract claim against a mortgage servicer because the borrower was in substantial arrears, and “as a general principle . . . an individual in breach cannot bring a cause of action for breach against another contracting party.” The Fifth Circuit reversed, finding that the borrower had alleged plausible claims that the servicer breached first; specially, that “the misapplication of [the borrrower’s] payments to an escrow account, resulting in default . . . constituted a material breach,” and that “Chase’s rejection of her mortgage payments, even if not a material breach, rendered performance impossible and that, as a result, any subsequent breach does not bar her claim.” Peters v. JP Morgan Chase, No. 13-50157 (Jan. 23, 2015, unpublished).

The actual pleading is available here, the key averment appears in paragaph 8: “According to the information received from the bank, Defendant believes Plaintiff is over $50,000 in arrears. According to the accounting done by Plaintiff, Plaintiff only owes $31, 437.30. Only $15,000 of this amount is on past due payments. Plaintiff believes that the disparity between the two figures is due to the fact that Chase has misapplied her payments under the mortgage to escrow fund, thereby causing her to be in default under the mortgage.”

I hope you enjoy this article on “Fact Issues in the Fifth Circuit,” which I published earlier this month in the State Bar Litigation Section’s periodical, “News for the Bar.”

The Fifth Circuit revised its original opinion in BNSF Railway Co. v. United States to expand and revise the discussion of ambiguity as part of the Chevron analysis of an IRS regulation; the outcome remained unchanged. No. 13-10014 (Jan. 15, 2015). The new discussion includes a reminder about the limited role of dictionaries, from the venerable en banc opinion about regulations for chicken processing in Mississippi Poultry Association, Inc. v. Madigan, 31 F.3d 293 (5th Cir.1994). The canon of “noscitur a sociis” (“an ambiguous term may be given more precise context by the neighboring words with which it is associated” also makes one of its infrequent appearances.

The Fifth Circuit revised its original opinion in BNSF Railway Co. v. United States to expand and revise the discussion of ambiguity as part of the Chevron analysis of an IRS regulation; the outcome remained unchanged. No. 13-10014 (Jan. 15, 2015). The new discussion includes a reminder about the limited role of dictionaries, from the venerable en banc opinion about regulations for chicken processing in Mississippi Poultry Association, Inc. v. Madigan, 31 F.3d 293 (5th Cir.1994). The canon of “noscitur a sociis” (“an ambiguous term may be given more precise context by the neighboring words with which it is associated” also makes one of its infrequent appearances.

Lexington Relocation Services sued Gum Tree Property Management and other defendants, alleging that a former employee had been hired by them to perform “substantially the same marketing and sales tasks that she had previously performed, in violation of her employment agreement.” Nationwide Mutual Ins. Co. v. Gum Tree Property Management, No. 14-60302 (Jan. 14, 2015, unpublished). Gum Tree sought defense and indemnity under several CGL and umbrella policies; the district court ruled for the insurer and the Fifth Circuit affirmed. The Court held that the insured did not successfully invoke a “narrow exception” under Mississippi law that can base coverage on “true facts” learned by the insurer beyond what a pleading says, noting that the exception does not reach “simpl[e] denials of the allegations in the complaint” or other “mere assertions.” The Court then found that the pleading did not make allegations about disparagement, invasion of privacy, or advertising injury.

Lexington Relocation Services sued Gum Tree Property Management and other defendants, alleging that a former employee had been hired by them to perform “substantially the same marketing and sales tasks that she had previously performed, in violation of her employment agreement.” Nationwide Mutual Ins. Co. v. Gum Tree Property Management, No. 14-60302 (Jan. 14, 2015, unpublished). Gum Tree sought defense and indemnity under several CGL and umbrella policies; the district court ruled for the insurer and the Fifth Circuit affirmed. The Court held that the insured did not successfully invoke a “narrow exception” under Mississippi law that can base coverage on “true facts” learned by the insurer beyond what a pleading says, noting that the exception does not reach “simpl[e] denials of the allegations in the complaint” or other “mere assertions.” The Court then found that the pleading did not make allegations about disparagement, invasion of privacy, or advertising injury.

The issue in Vine Street LLC v. Borg Warner Corp. was whether the defendant — a seller of dry cleaning equipment and supplies — intentionally discharged “PERC” (an unpleasant chemical widely used in dry cleaning) into the ground. No. 07-40440 (Jan. 14, 2015). While most of the opinion addresses technical matters about CERCLA , the discussion about the evidence of intent is of general interest. In particular, the Court noted testimony that the defendant’s employees handled PERC with care and did not intentionally spill it, and evidence that the defendant’s intent was to “sell useful chemicals to distributors and not to dispose of them” — in other words, “there is no evidence to suggest that [Defendant] engaged in subterfuge to disguise the disposal of PERC as a legitimate transaction surrounding the operation of a dry cleaning business.”

The case of AAA Bonding Agency v. United States Dep’t of Homeland Security involved the seldom-seen world of “immigration bonds” — a type of surety bond that allows release of an alien from custody while deportation proceedings are ongoing. No. 14-20057 (Jan. 12, 2015, unpublished). The Fifth Circuit has previously held that “DHS may only enforce an immigration bond against a surety company or bonding agent that has received notice demanding delivery of the alien covered by the bond.” This case involved 23 bonds where (1) AAA, the bonding agency, was liable on the bond with Surety National, an insurance company, (2) only AAA had received notice from DHS, and (3) Surety National had settled with DHS, and as part of the settlement, agreed that AAA would not be liable to DHS on these bonds if a court held that AAA’s obligation was joint and several with Surety National’s. The Court concluded that its prior holding did not alter the joint and several liability of AAA and Surety National as set forth in the language of the bonds, and ruled for AAA.

The case of AAA Bonding Agency v. United States Dep’t of Homeland Security involved the seldom-seen world of “immigration bonds” — a type of surety bond that allows release of an alien from custody while deportation proceedings are ongoing. No. 14-20057 (Jan. 12, 2015, unpublished). The Fifth Circuit has previously held that “DHS may only enforce an immigration bond against a surety company or bonding agent that has received notice demanding delivery of the alien covered by the bond.” This case involved 23 bonds where (1) AAA, the bonding agency, was liable on the bond with Surety National, an insurance company, (2) only AAA had received notice from DHS, and (3) Surety National had settled with DHS, and as part of the settlement, agreed that AAA would not be liable to DHS on these bonds if a court held that AAA’s obligation was joint and several with Surety National’s. The Court concluded that its prior holding did not alter the joint and several liability of AAA and Surety National as set forth in the language of the bonds, and ruled for AAA.

Plaintiffs — breeders of quarter horses using cloning technology — sued the American Quarter Horse Association, alleging that its bar on the registry of cloned horses was anticompetitive and violated Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act. Abraham & Veneklasen Joint Venture v. American Quarter Horse Association, No. 13-11043 (Jan. 14, 2015). The district court agreed and entered an injunction; the Fifth Circuit reversed.

Plaintiffs — breeders of quarter horses using cloning technology — sued the American Quarter Horse Association, alleging that its bar on the registry of cloned horses was anticompetitive and violated Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act. Abraham & Veneklasen Joint Venture v. American Quarter Horse Association, No. 13-11043 (Jan. 14, 2015). The district court agreed and entered an injunction; the Fifth Circuit reversed.

With respect to the Section 1 (conspiracy) claim, the Court expressed skepticism about whether the Association’s management could legally conspire with the Association, noting (without deciding): “American Needle‘s rejection of ‘single entity’ status for organizations with ‘separate economic actors’ [such as the NFL as to licensing] does not fit comfortably with the facts before us. AQHA is more than a sports league, it is not a trade association, and its quarter million members are involved in ranching, horse trading, pleasure riding and many other activities besides the ‘elite Quarter Horse’ market.” The Court then held that Plaintiffs had not shown a conspiracy, finding that their evidence about powerful members of the Association speaking out against cloning did not prove an actual agreement: “[T]he antitrust laws are not intended as a device to review the details of parliamentary procedure.” (citation omitted)

As to the Section 2 claim, the Court observed: “AQHA is a member organization; it is not engaged in breeding, racing, selling or showing elite Quarter Horses.” Thus, because “nothing in the record . . . shows that AQHA competes in the elite Quarter Horse Market,” no claim about its alleged monopolization of that market was cognizable. The Court distinguished other cases in which a trade association actually became a market participant and competitor.

As to the Section 2 claim, the Court observed: “AQHA is a member organization; it is not engaged in breeding, racing, selling or showing elite Quarter Horses.” Thus, because “nothing in the record . . . shows that AQHA competes in the elite Quarter Horse Market,” no claim about its alleged monopolization of that market was cognizable. The Court distinguished other cases in which a trade association actually became a market participant and competitor.

Waste Management sued Kattler, a former employee, for misappropriating confidential information and other related claims. A dispute about what information Kattler had in is possession expanded to include a contempt finding against Kattler’s attorney, Moore. Waste Management v. Kattler, No. 13-20356 (Jan. 15, 2015). The Fifth Circuit reversed, reasoning as follows:

Waste Management sued Kattler, a former employee, for misappropriating confidential information and other related claims. A dispute about what information Kattler had in is possession expanded to include a contempt finding against Kattler’s attorney, Moore. Waste Management v. Kattler, No. 13-20356 (Jan. 15, 2015). The Fifth Circuit reversed, reasoning as follows:

1. The order setting a hearing referenced a motion, by Pacer docket number, that only sought relief against Kattler and not the attorney. It was not an adequate “show-cause order naming [both] Moore and Kattler as alleged contemnors[.]”

2. On the merits, the Court found that Kattler had misled Moore as to the existence of a particular “San Disk thumb drive,” that Moore had acted prudently in consulting ethics counsel and withdrawing after he learned of the untruthfulness, and that new counsel made a prompt disclosure about the drive that avoided unfair prejudice. This part of the opinion reviews Circuit authority about the failure to correct incorrect court filings.

3. Also on the merits, “while Moore clearly failed to comply with the terms of the December 20 preliminary injunction by not producing the iPad image directly to [Waste Management] by December 22, this failure is excusable because the order required Moore to violate the attorney-client privilege.” Further, the relevant order only “required Kattler to produce an image of the device only, not the device itself,” which created a “degree of confusion” that excused the decision not to produce the actual iPad.

Law360 has also reported on this decision, and an expanded version of this article appears in the Texas Lawbook.

Eastman Chemical, the manufacturer of a plastic resin used in water bottles and food containers, successfully sued Plastipure under the Lanham Act, alleging that Plastipure falsely advertised that Eastman’s resin contained a dangerous and unhealthy additive. Eastman Chemical Co. v. Plastipure, Inc., No. 13-51087 (Dec. 22, 2014). Relying on ONY, Inc. v. Cornerstone Therapeutics, Inc., 720 F.3d 490 (2d Cir. 2013), Plastipure argued that “commercial statements relating to live scientific controversies should be treated as opinions for Lanham Act purposes.” The Fifth Circuit disagreed, noting that Plastipure made these statements in commercial ads rather than scientific literature, and observing: “Otherwise, the Lanham Act would hardly ever be enforceable — ‘many, if not most, products may be tied to public concerns with the environment, energy, economic policy, or individual health and safety.'” The Court also rejected challenges to the jury instructions and to the sufficiency of the evidence as to falsity.

Eastman Chemical, the manufacturer of a plastic resin used in water bottles and food containers, successfully sued Plastipure under the Lanham Act, alleging that Plastipure falsely advertised that Eastman’s resin contained a dangerous and unhealthy additive. Eastman Chemical Co. v. Plastipure, Inc., No. 13-51087 (Dec. 22, 2014). Relying on ONY, Inc. v. Cornerstone Therapeutics, Inc., 720 F.3d 490 (2d Cir. 2013), Plastipure argued that “commercial statements relating to live scientific controversies should be treated as opinions for Lanham Act purposes.” The Fifth Circuit disagreed, noting that Plastipure made these statements in commercial ads rather than scientific literature, and observing: “Otherwise, the Lanham Act would hardly ever be enforceable — ‘many, if not most, products may be tied to public concerns with the environment, energy, economic policy, or individual health and safety.'” The Court also rejected challenges to the jury instructions and to the sufficiency of the evidence as to falsity.

While affirming the dismissal of the borrowers’ other claims related to a foreclosure, the Fifth Circuit reversed as to a claim for wrongful foreclosure, reasoning: “Under Texas law, a claim for wrongful foreclosure generally requires: (1) ‘a defect in the foreclosure sale proceedings;’ (2) ‘a grossly inadequate selling price;’ and (3) ‘a causal connection between the defect and grossly inadequate selling price.’ In their Third Amended

Complaint, Plaintiffs allege that JPMC failed to comply with the notice procedures required for a foreclosure sale,and that, as a result, they lost the opportunity to obtain cash or to find a buyer for the Property before JPMC foreclosed. Plaintiffs also specifically allege that the Property sold for a grossly inadequate sales price.” Guajardo v. JP Morgan Chase Bank, N.A., No. 13-51025 (Jan. 12, 2015, unpublished) (citations omitted). Notably, while the pleading describes the type of notice required and avers that it did not occur, it does not provide detail about the sales price and why it was not adequate.