A party sought to appeal a ruling in a forfeiture action about the M/V Galactica Star (distinct from the Battlestar Galactica, right); the Fifth Circuit dismissed for lack of jurisdiction: “Although a “Final Judgment” was signed and entered in district court, it did not reference Rule 54(b), did not include any language taken from the rule,and did not express the sentiments contained within the rule. The only document referenced in the judgment was the Government’s motion to strike, which did

A party sought to appeal a ruling in a forfeiture action about the M/V Galactica Star (distinct from the Battlestar Galactica, right); the Fifth Circuit dismissed for lack of jurisdiction: “Although a “Final Judgment” was signed and entered in district court, it did not reference Rule 54(b), did not include any language taken from the rule,and did not express the sentiments contained within the rule. The only document referenced in the judgment was the Government’s motion to strike, which did  not mention Rule 54(b), the language of the rule, partial finality, or immediate appealability.” United States v. The MV Galactica Star, No. 18-20781 (Oct. 1, 2019). Cf. Lehmann v. Har-Con Corp., 39 S.W.3d 191 (Tex. 2001) (“[W]hen there has not been a conventional trial on the merits, an order or judgment is not final for purposes of appeal unless it actually disposes of every pending claim and party or unless it clearly and unequivocally states that it finally disposes of all claims and all parties.” (emphasis added)).

not mention Rule 54(b), the language of the rule, partial finality, or immediate appealability.” United States v. The MV Galactica Star, No. 18-20781 (Oct. 1, 2019). Cf. Lehmann v. Har-Con Corp., 39 S.W.3d 191 (Tex. 2001) (“[W]hen there has not been a conventional trial on the merits, an order or judgment is not final for purposes of appeal unless it actually disposes of every pending claim and party or unless it clearly and unequivocally states that it finally disposes of all claims and all parties.” (emphasis added)).

While focused on the intricate McDonnell-Douglas burden-shifting framework (a structure described in more than one Fifth Circuit opinion as “kudzu-like“), Garcia v. Professional Contract Servcs. Inc provides general insight about creation of a genuine issue of material fact.

While focused on the intricate McDonnell-Douglas burden-shifting framework (a structure described in more than one Fifth Circuit opinion as “kudzu-like“), Garcia v. Professional Contract Servcs. Inc provides general insight about creation of a genuine issue of material fact.

As to the plaintiff’s prima facie case, all parties agreed that “proximity in time” – the passage of only 76 days between the plaintiff’s protected whistleblowing activity and termination – was sufficient to meet this burden.

As to pretext, while temporal proximity alone is not enough, the Fifth Circuit found a genuine issue of fact when the plaintiff pointed to: “(1) temporal proximity between his protected activity and his firing; (2) his dispute of the facts leading up to his termination; (3) a similarly situated employee who was not terminated for similar conduct; (4) harassment from his supervisor after the company knew of his protected whistleblowing conduct; (5) the ultimate stated reason for the company’s termination of [plaintiff] had been known to the compan y for years; and (6) the company stood to lose millions of dollars if its conduct was discovered.” The Court also disagreed with the district court about whether the “similarly situated” employee identified by the plaintiff qualified as such, noting that while they worked in different divisions: “Rodas and Garcia had identical jobs, reported to the same people, had a similar history of infractions, and both made mistakes overseeing Job 560.” No. 18-50144 (Sept. 11, 2019).

y for years; and (6) the company stood to lose millions of dollars if its conduct was discovered.” The Court also disagreed with the district court about whether the “similarly situated” employee identified by the plaintiff qualified as such, noting that while they worked in different divisions: “Rodas and Garcia had identical jobs, reported to the same people, had a similar history of infractions, and both made mistakes overseeing Job 560.” No. 18-50144 (Sept. 11, 2019).

Are unpublished opinions introducing murkiness into a legal issue? Rein them in with Garcia v. Professional Contract Servcs., Inc., No. 18-50144, (Sept. 11, 2019), which:

Are unpublished opinions introducing murkiness into a legal issue? Rein them in with Garcia v. Professional Contract Servcs., Inc., No. 18-50144, (Sept. 11, 2019), which:

- Limited their holdings: “The company points to a couple of unpublished decisions of our court that have flagged the circuit split over this issue. These decisions do not reference

the binding Fifth Circuit precedent on this point because they did not need to: both decisions resolved the cases before them on other grounds.” (citations omitted); and

the binding Fifth Circuit precedent on this point because they did not need to: both decisions resolved the cases before them on other grounds.” (citations omitted); and - Dismissed their precedential value: “To the extent some unpublished cases have introduced murkiness into the case law in this area, that confusion should be resolved by applying our binding precedent.”

600Camp and 600Commerce are recognized in the first-ever list of “Texas Trailblazers,” as just published by Texas Lawyer!

600Camp and 600Commerce are recognized in the first-ever list of “Texas Trailblazers,” as just published by Texas Lawyer!

If you are litigating a Texas contract-law case and feel the need to scratch an equitable itch – don’t: “The Supreme Court of Texas has observed that the interpretive role of judges ‘is to be neither generous nor parsimonious’ but unswervingly faithful to what the words actually say. Looser atextual readings may scratch an equitable itch, or at times seem more pragmatic. But the Texas High Court adheres to this centuries-old principle—’law, without equity, though hard and disagreeable, is much more desirable for the public good, than equity without law: which would make every judge a legislator, and introduce the most infinite confusion.’ Texas precedent is no-nonsense about giving words their most forthright, contextual meaning. Plain language forbids judicial ad-libbing. Here, the text is clear. And, at least in Texas, clear text = controlling text.” Weaver v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., No. 18-10517 (Sept. 20, 2019).

If you are litigating a Texas contract-law case and feel the need to scratch an equitable itch – don’t: “The Supreme Court of Texas has observed that the interpretive role of judges ‘is to be neither generous nor parsimonious’ but unswervingly faithful to what the words actually say. Looser atextual readings may scratch an equitable itch, or at times seem more pragmatic. But the Texas High Court adheres to this centuries-old principle—’law, without equity, though hard and disagreeable, is much more desirable for the public good, than equity without law: which would make every judge a legislator, and introduce the most infinite confusion.’ Texas precedent is no-nonsense about giving words their most forthright, contextual meaning. Plain language forbids judicial ad-libbing. Here, the text is clear. And, at least in Texas, clear text = controlling text.” Weaver v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., No. 18-10517 (Sept. 20, 2019).

On October 1, the term of Hon. Priscilla Owen begins as Chief Judge of the Fifth Circuit. The Court’s official press release provides background information. Every best wish to Chief Judge Owen in this important position.

On October 1, the term of Hon. Priscilla Owen begins as Chief Judge of the Fifth Circuit. The Court’s official press release provides background information. Every best wish to Chief Judge Owen in this important position.

In Simmons v. Pacific Bells LLC, the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment against a Taco Bell employee who claimed he was retaliated against for going to jury duty. In particular –

He raised specific facts indicating that his termination for tardiness may have been pretextual. First, Simmons was tardy less often than other coworkers, yet those coworkers were not terminated and did not suffer adverse employment action. Second, he was never once warned about his tardiness prior to his termination. Third, Simmons demonstrated that some of his tardiness resulted from Pacific Bells’s business practices. Fourth, he was terminated immediately following his jury service. Fifth, the individual who told Simmons to lie recommended his termination and was present for it. Sixth, the individual who terminated Simmons stated in an email that she had “several different routes I can go with his termination. . . . I want to focus on [his] excessive tardiness.” In sum, the timing of Simmons’s termination, combined with the arguably pretextual rationale for his firing, could lead a reasonable jury to conclude that he was fired as a result of his refusal to lie to avoid jury service.

The Court declined to address a related issue about the scope of the “interested witness” doctrine in summary-judgment practice. No. 19-60001 (Sept. 27, 2019) (unpublished).

The Fifth Circuit (minus the two Mississippi judges, who are) voted to take en banc the difficult voting rights case of Thomas v. Bryant, No. 19-60133 (as revised, Sept. 3, 2019), which also presents important issues about justiciability and appellate procedure. At the panel level, all three judges wrote opinions.

The Fifth Circuit (minus the two Mississippi judges, who are) voted to take en banc the difficult voting rights case of Thomas v. Bryant, No. 19-60133 (as revised, Sept. 3, 2019), which also presents important issues about justiciability and appellate procedure. At the panel level, all three judges wrote opinions.

The district court held a jury trial on whether Gilbert Galan had notice of Valero Energy’s (his employer) arbitration program. Valero called the arbitation program “Dialogue”; the jury charge asked whether “Valero prove[d] by a preponderance of the evidence that it gave unequivocal notice  to Gilbert Galan, Jr. of definite changes in employment terms regarding Valero’s Dialogue program[,]” Additionally, an instruction said that the “sole issue in this trial is whether Defendant[] Valero . . . notified plaintiff of the arbitration program and its mandatory nature.” Galan objected that the question did not have the word “arbitration”; “[h]is point is that the jury could have concluded Galan knew about the Dialogue Program as a whole, but not the part of it requiring arbitration.” The Fifth Circuit found no abuse of discretion in denying that request, especially given the instruction accompanying the question. Galan v. Valero Services, Inc., No. 19-400753 (Sept. 23, 2019) (unpublished).

to Gilbert Galan, Jr. of definite changes in employment terms regarding Valero’s Dialogue program[,]” Additionally, an instruction said that the “sole issue in this trial is whether Defendant[] Valero . . . notified plaintiff of the arbitration program and its mandatory nature.” Galan objected that the question did not have the word “arbitration”; “[h]is point is that the jury could have concluded Galan knew about the Dialogue Program as a whole, but not the part of it requiring arbitration.” The Fifth Circuit found no abuse of discretion in denying that request, especially given the instruction accompanying the question. Galan v. Valero Services, Inc., No. 19-400753 (Sept. 23, 2019) (unpublished).

The 600Camp blog celebrates its birthday this week, and invites you to join the festivity with some shrimp remoulade; here’s the recipe from Galatoire’s so you can spice up your week!

The 600Camp blog celebrates its birthday this week, and invites you to join the festivity with some shrimp remoulade; here’s the recipe from Galatoire’s so you can spice up your week!

Another discovery dispute in litigation about governance of the airport in Jackson, Mississippi (a previous proceeding involved a mandamus proceeding related to the deposition of the governor’s chief of staff) arose from subpoenas to several legislators, who asserted legislative privilege in response. The Fifth Circuit found that the plaintiffs lacked standing (“The plaintiffs cite no precedent supporting their theory that Jackson voters have a right to elect officials with the exclusive authority to select municipal airport commissioners”), and that this issue was properly raised even during an interlocutory appeal of a collateral order: “[E]ven nonparty witnesses refusing to comply with a discovery order may challenge standing . . . because ‘the subpoena power of a court cannot be more extensive than its jurisdiction.'” Stallworth v. Bryant, No. 18-60587 (Aug. 21, 2019).

Another discovery dispute in litigation about governance of the airport in Jackson, Mississippi (a previous proceeding involved a mandamus proceeding related to the deposition of the governor’s chief of staff) arose from subpoenas to several legislators, who asserted legislative privilege in response. The Fifth Circuit found that the plaintiffs lacked standing (“The plaintiffs cite no precedent supporting their theory that Jackson voters have a right to elect officials with the exclusive authority to select municipal airport commissioners”), and that this issue was properly raised even during an interlocutory appeal of a collateral order: “[E]ven nonparty witnesses refusing to comply with a discovery order may challenge standing . . . because ‘the subpoena power of a court cannot be more extensive than its jurisdiction.'” Stallworth v. Bryant, No. 18-60587 (Aug. 21, 2019).

Cleveland v. Bell was a wrongful death claim, asserted under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, which turned on the allegation that a prison nurse was indifferent to the decedent’s calls for help. The trial court denied qualified immunity to the nurse and the Fifth Circuit reversed: “[W]e find no evidence that . . . Nurse Bell subjectively ‘dr[e]w the inference’ that Cleveland was experiencing a life-threatening medical emergency. The record contains statements from Nurse Bell indicating that she thought there was nothing wrong with Cleveland and believed he was faking illness.But nothing suggests that these statements reflected anything other than her sincere opinion at the time. Even if we construe her statements in the light most favorable to Plaintiffs, they are insufficient to establish that Nurse Bell knew how serious the situation was.” No. 18-30968 (Sept. 13, 2019) (emphasis added).

Cleveland v. Bell was a wrongful death claim, asserted under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, which turned on the allegation that a prison nurse was indifferent to the decedent’s calls for help. The trial court denied qualified immunity to the nurse and the Fifth Circuit reversed: “[W]e find no evidence that . . . Nurse Bell subjectively ‘dr[e]w the inference’ that Cleveland was experiencing a life-threatening medical emergency. The record contains statements from Nurse Bell indicating that she thought there was nothing wrong with Cleveland and believed he was faking illness.But nothing suggests that these statements reflected anything other than her sincere opinion at the time. Even if we construe her statements in the light most favorable to Plaintiffs, they are insufficient to establish that Nurse Bell knew how serious the situation was.” No. 18-30968 (Sept. 13, 2019) (emphasis added).

A surprisingly subtle problem can arise under secction 2.316 of the UCC when a party urges a role for implied warranties, even though the parties’ agreement contains express ones. A comment to that section advises: “The situation in which the buyer gives precise and complete specifications as to the seller is not explicitly covered in this section, but this is a frequent circumstance by which the implied warranties may be excluded.” In Baker Hughes v. UE Compression, the Fifth Circuit found such a situation when:

A surprisingly subtle problem can arise under secction 2.316 of the UCC when a party urges a role for implied warranties, even though the parties’ agreement contains express ones. A comment to that section advises: “The situation in which the buyer gives precise and complete specifications as to the seller is not explicitly covered in this section, but this is a frequent circumstance by which the implied warranties may be excluded.” In Baker Hughes v. UE Compression, the Fifth Circuit found such a situation when:

. .. this Agreement included 18 single-space pages of Baker Hughes’s Specification and a 21-page responsive set of specifications comprising UE’s Quote. Baker Hughes ordered exactly what it required in the boosters. Other contractual provisions cited above confirm Baker Hughes’s ultimate responsibility for the design, its duty to supply technical information, its ability to modify specs during the fabrication, and its right to approve any drawings or specifications prepared by UE

Mo. 17-20709 (Sept. 12, 2019) (Our firm’s state-court brief on the topic in an unrelated case shows some of the potential complexities about this UCC issue.)

The Flying Dutchman is a mythical ship that forever travels the seas, unable to find a port. Conn Appliances, Inc. v. Williams presents a similar tale about a dispute involving a retail installment contract. Williams sued Conn in Tennessee, realized that he had an arbitration agreement in his contract, and then dismissed his suit in favor of arbitration in Tennessee (the clause required arbitration “near his residence”). Williams won; he filed suit in Tennessee to enforce the award while Conn filed sued in its

The Flying Dutchman is a mythical ship that forever travels the seas, unable to find a port. Conn Appliances, Inc. v. Williams presents a similar tale about a dispute involving a retail installment contract. Williams sued Conn in Tennessee, realized that he had an arbitration agreement in his contract, and then dismissed his suit in favor of arbitration in Tennessee (the clause required arbitration “near his residence”). Williams won; he filed suit in Tennessee to enforce the award while Conn filed sued in its  home state of Texas to vacate it (the clause allowed confirmation in “any court with jurisdiction”). The Fifth Circuit agreed that Williams was not subject to personal jurisdiction in Texas, and affirmed the dismissal of that action. Conn protested that it was not subject to jurisdiction in Tennessee, and the Court observed: “[E]ven if the Western District of Tennessee is not the proper forum, the lack of jurisdiction over Conn in another forum does not mean that the Southern District of Texas has personal jurisdiction over Williams.” No. 19-20139 (Sept. 4, 2019).

home state of Texas to vacate it (the clause allowed confirmation in “any court with jurisdiction”). The Fifth Circuit agreed that Williams was not subject to personal jurisdiction in Texas, and affirmed the dismissal of that action. Conn protested that it was not subject to jurisdiction in Tennessee, and the Court observed: “[E]ven if the Western District of Tennessee is not the proper forum, the lack of jurisdiction over Conn in another forum does not mean that the Southern District of Texas has personal jurisdiction over Williams.” No. 19-20139 (Sept. 4, 2019).

An accounting firm successfully defended against a malpractice claim by relying on Mississippi’s “minutes rule,” under which “Mississippi courts will not give legal effect to a contract with a public board unless the board’s approval of the contract is reflected in its minutes.” After losing a summary judgment, the plaintiff (a county hospital) “attempted to submit additional evidence into the record to prove the existence of a professional relationship with Horne—namely, minutes from the board’s regular session meetings on January 19, 2011 and March 16, 2011, as well as minutes from the board’s executive session meetings. . . . The Medical Center admitted, however, that this evidence was in fact not new at all—the Center had access to its own minutes throughout the proceedings. It nevertheless sought to excuse its tardiness on the ground that the minutes became relevant only when the district court granted summary judgment to Horne.” (emphasis added). The district court rejected that explanation, and so did the Fifth Circuit. Lefoldt v. Horne LLP, No. 18-60581 (Sept. 6, 2019).

An accounting firm successfully defended against a malpractice claim by relying on Mississippi’s “minutes rule,” under which “Mississippi courts will not give legal effect to a contract with a public board unless the board’s approval of the contract is reflected in its minutes.” After losing a summary judgment, the plaintiff (a county hospital) “attempted to submit additional evidence into the record to prove the existence of a professional relationship with Horne—namely, minutes from the board’s regular session meetings on January 19, 2011 and March 16, 2011, as well as minutes from the board’s executive session meetings. . . . The Medical Center admitted, however, that this evidence was in fact not new at all—the Center had access to its own minutes throughout the proceedings. It nevertheless sought to excuse its tardiness on the ground that the minutes became relevant only when the district court granted summary judgment to Horne.” (emphasis added). The district court rejected that explanation, and so did the Fifth Circuit. Lefoldt v. Horne LLP, No. 18-60581 (Sept. 6, 2019).

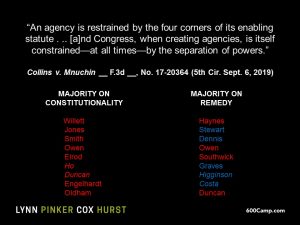

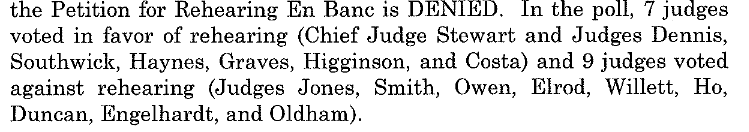

The full Fifth Circuit engaged the boundaries of the administrative state in Collins v. Mnuchin. A 9-7 majority of the en banc Court found that the FHFA (the regulator of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) was structured unconstitutionally; a different 9-7 majority found that the appropriate remedy was a go-forward restructure of the agency rather than the unwinding of a significant, previously-ordered financial transaction. (If the below is hard to read in your browser, just click on it to see it full-sized).

The full Fifth Circuit engaged the boundaries of the administrative state in Collins v. Mnuchin. A 9-7 majority of the en banc Court found that the FHFA (the regulator of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) was structured unconstitutionally; a different 9-7 majority found that the appropriate remedy was a go-forward restructure of the agency rather than the unwinding of a significant, previously-ordered financial transaction. (If the below is hard to read in your browser, just click on it to see it full-sized).

Four Republican appointees joined the majority on remedy, two of whom–Judges Owen and Duncan–had joined the majority on constitutionality.

Four Republican appointees joined the majority on remedy, two of whom–Judges Owen and Duncan–had joined the majority on constitutionality.

Among the various concurrences and dissents, Judges Ho and Oldham concurred to emphasize the significance of the case to other administrative agencies, while Judges Costa and Higginson dissented on the basis of the plaintiffs’ standing.

The diverse approaches of the Republican-appointed judges underscore the frequent observation on this blog that the term “conservative” is a broad umbrella for different perspectives on distinct aspects of the apparatus of government.

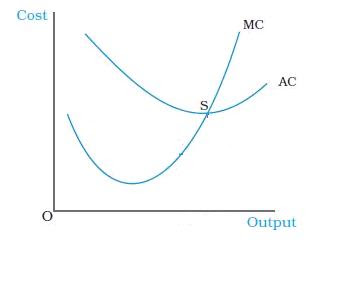

The question in French v. Linn Energy LLC was subordination; the analysis reviewed the Bankruptcy Code’s policy goals: “Section 510(b) serves to effectuate one of the general principles of corporate and bankruptcy law: that creditors are entitled to be paid ahead of shareholders in the distribution of corporate assets.” The Court reviewed this issue: “whether In this case we decide that payments owed to a shareholder by a bankrupt debtor, which are not quite dividends but which certainly look a lot like dividends, should be treated like the equity interests of a shareholder and subordinated to claims by creditors of the debtor,’ and concluded that they should be. No. 18-40369 (Sept. 3, 2019).

The question in French v. Linn Energy LLC was subordination; the analysis reviewed the Bankruptcy Code’s policy goals: “Section 510(b) serves to effectuate one of the general principles of corporate and bankruptcy law: that creditors are entitled to be paid ahead of shareholders in the distribution of corporate assets.” The Court reviewed this issue: “whether In this case we decide that payments owed to a shareholder by a bankrupt debtor, which are not quite dividends but which certainly look a lot like dividends, should be treated like the equity interests of a shareholder and subordinated to claims by creditors of the debtor,’ and concluded that they should be. No. 18-40369 (Sept. 3, 2019).

A securities-fraud class action lived to fight another day in Broyles v. Commonwealth Advisors: “The district court erred in deciding that plaintiffs lacked standing under Delaware law to bring a direct action against their investment advisers rather than initiating a derivative action in behalf of the hedge funds that the advisers had assembled and managed for fraudulent inducement purposes. The investor plaintiffs adequately supported their motion for partial summary judgment demonstrating their Article III standing with appropriate evidence of their injury-in-fact that arose :immediately upon their purchase of the falsely overvalued securities; were induced and caused by the defendant advisers’ fraudulent advice and solicitations; and likely will be redressed by a favorable decision on the merits.” No. 17-30092 (Aug. 28, 2019).

A securities-fraud class action lived to fight another day in Broyles v. Commonwealth Advisors: “The district court erred in deciding that plaintiffs lacked standing under Delaware law to bring a direct action against their investment advisers rather than initiating a derivative action in behalf of the hedge funds that the advisers had assembled and managed for fraudulent inducement purposes. The investor plaintiffs adequately supported their motion for partial summary judgment demonstrating their Article III standing with appropriate evidence of their injury-in-fact that arose :immediately upon their purchase of the falsely overvalued securities; were induced and caused by the defendant advisers’ fraudulent advice and solicitations; and likely will be redressed by a favorable decision on the merits.” No. 17-30092 (Aug. 28, 2019).

Conservative thinkers frequently express skepticism about the administrative state, and in particular, the Chevron doctrine about judicial deference to it. A powerful counterpoint to that line of thinking, and an equally orthodox part of conservative philosophy, appears in the Fifth Circuit’s recent opinion in Center for Biological Diversity v. EPA, which found a lack of standing to challenge an EPA discharge permit and reminded: “’For the federal courts to decide questions of law arising outside of cases and controversies would be inimical to the Constitution’s democratic character.’ It would improperly transform courts into ‘roving commissions assigned to pass judgment on the validity of the Nation’s laws’ and agency actions. In our Government, there are entities that address environmental issues outside of the case-or-controversy constraint. This Court is not one of them. As Judge Sentelle put it many years ago: ‘The federal judiciary is not a backseat Congress nor some sort of super-agency.’“ No. 18-60102 (Aug. 30, 2019) (citations omitted).

Conservative thinkers frequently express skepticism about the administrative state, and in particular, the Chevron doctrine about judicial deference to it. A powerful counterpoint to that line of thinking, and an equally orthodox part of conservative philosophy, appears in the Fifth Circuit’s recent opinion in Center for Biological Diversity v. EPA, which found a lack of standing to challenge an EPA discharge permit and reminded: “’For the federal courts to decide questions of law arising outside of cases and controversies would be inimical to the Constitution’s democratic character.’ It would improperly transform courts into ‘roving commissions assigned to pass judgment on the validity of the Nation’s laws’ and agency actions. In our Government, there are entities that address environmental issues outside of the case-or-controversy constraint. This Court is not one of them. As Judge Sentelle put it many years ago: ‘The federal judiciary is not a backseat Congress nor some sort of super-agency.’“ No. 18-60102 (Aug. 30, 2019) (citations omitted).

“Incentive alignment” is a well-known business concept; in law, various types of fee arrangements are often employed to align the financial motivations of lawyer and client. The law is also wary of incentives for injustice, especially when the finances of the justice system become muddled with court procedure. A recent Fifth Circuit opinion joined the list of the clearest examples of such misalignments:

“Incentive alignment” is a well-known business concept; in law, various types of fee arrangements are often employed to align the financial motivations of lawyer and client. The law is also wary of incentives for injustice, especially when the finances of the justice system become muddled with court procedure. A recent Fifth Circuit opinion joined the list of the clearest examples of such misalignments:

- Tumey v. Ohio, 273 U.S. 510 (1927), which found a due process violation when a “liquor court,” which prosecuted violations of the state Prohibition Act, allowed the mayor to serve as the judge and convict without a jury. If the mayor found the defendant guilty, some of the fine paid would go towards the mayor’s “costs in each case, in addition to his regular salary”; an acquittal, on the other hand, meant no money to the mayor;

- Brown v. Vance, 637 F.2d 272 (5th Cir. 1981), invalidating the statutory fee system for compensating Mississippi justices of the peace because those judges’ compensation depended on the number of cases filed in their courts (thus incentivizing them to rule for plaintiffs in civil cases and the prosecution in criminal ones to encourage more filings); and now

- Caliste v. Cantrell, No. 18-30954 (Aug. 29, 2019), finding a due process violation “[w]hen a defendant has to buy a commercial surety bond, [and] a portion of the bond’s value goes to a fund for judges’ expenses . . . [so] the more often the magistrate requires a secured money bond as a condition of release, the more money the court has to cover expenses.”

Double Eagle Energy Services filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection and then sued two defendants for breach of contract in federal district court. Double Eagle then assigned that claim to one of its creditors; the defendants argued that this assignment destroyed federal subject matter jurisdiction. The Fifth Circuit disagreed, relying upon the “time-of-filing” rule to find that the “related to bankruptcy” jurisdiction existing when the case was filed continued to exist after the assignment. The separate question–whether the district court should nevertheless its exercise discretion to dismiss the case–was remanded, as the Court’s “ordinary practice for discretionary decisions is remanding to ‘allow the district court to exercise its discretion in the first instance.'” Double Eagle Energy Services v. Markwest Utica EMG, No. 19-30207 (Aug. 26, 2019).

Double Eagle Energy Services filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection and then sued two defendants for breach of contract in federal district court. Double Eagle then assigned that claim to one of its creditors; the defendants argued that this assignment destroyed federal subject matter jurisdiction. The Fifth Circuit disagreed, relying upon the “time-of-filing” rule to find that the “related to bankruptcy” jurisdiction existing when the case was filed continued to exist after the assignment. The separate question–whether the district court should nevertheless its exercise discretion to dismiss the case–was remanded, as the Court’s “ordinary practice for discretionary decisions is remanding to ‘allow the district court to exercise its discretion in the first instance.'” Double Eagle Energy Services v. Markwest Utica EMG, No. 19-30207 (Aug. 26, 2019).

A vocational school (RRCC) sought to recover damages from the federal government’s civil forfeiture of $4 million from it, arguing that the seizure without notice put it out of business. the Fifth Circuit found the school’s claims barred by sovereign immunity: “Congress has provided various remedies for claimants like RRCC who assert that the United States has wrongfully seized their property in forfeiture proceedings. Under certain circumstances, claimants who “substantially prevail[ ]” in a forfeiture action may recover attorneys’ fees, costs, and interest. In some cases, they may sue the United States for property damages under the FTCA. .What claimants may not do, however, is sue the United States for constitutional torts arising out of the property seizure. Congress has not waived the United States’ sovereign immunity for damages claims of that nature. Because RRCC’s counterclaims sought precisely those kinds of damages, we hold its counterclaims are barred by sovereign immunity.” United States v. $4,480,466.16, No. 18-10801 (Aug. 22, 2019), withdrawn and revised (Nov. 5, 2019).

A vocational school (RRCC) sought to recover damages from the federal government’s civil forfeiture of $4 million from it, arguing that the seizure without notice put it out of business. the Fifth Circuit found the school’s claims barred by sovereign immunity: “Congress has provided various remedies for claimants like RRCC who assert that the United States has wrongfully seized their property in forfeiture proceedings. Under certain circumstances, claimants who “substantially prevail[ ]” in a forfeiture action may recover attorneys’ fees, costs, and interest. In some cases, they may sue the United States for property damages under the FTCA. .What claimants may not do, however, is sue the United States for constitutional torts arising out of the property seizure. Congress has not waived the United States’ sovereign immunity for damages claims of that nature. Because RRCC’s counterclaims sought precisely those kinds of damages, we hold its counterclaims are barred by sovereign immunity.” United States v. $4,480,466.16, No. 18-10801 (Aug. 22, 2019), withdrawn and revised (Nov. 5, 2019).

The Fifth Circuit confirmed a district judge’s broad discretion over discovery in JP Morgan Chase Bank v. Datatreasury, a dispute about the scope of postjudgment discovery in a licensing dispute won by Chase. The Court held that the district court did not abuse its discretion in:

The Fifth Circuit confirmed a district judge’s broad discretion over discovery in JP Morgan Chase Bank v. Datatreasury, a dispute about the scope of postjudgment discovery in a licensing dispute won by Chase. The Court held that the district court did not abuse its discretion in:

- Setting a time period for relevant information, considering the scope of the judgment and the pertinent licensing agreement;

- Focusing the relevant information by reference to the judgment itself rather than the broader definition of a “creditor” under the fraudulent-transfer statutes; and

- Evaluating the “proportionality” of the requested information in light of the expense associated with older records.

No. 18-40043 (Aug. 23, 2019).

Nearly a century ago, the unfortunate Helen Palsgraf was injured in a Long Island Railroad station; the difficult tort-law issues arising from her injury continue to challenge the courts today. Martinez v. Walgreens Co. presented the question “whether, under Texas law, a pharmacy owes a duty of care to third parties injured on the road by a customer who was negligently given someone else’s prescription.” The Fifth Circuit answered “no,” considering, inter alia: (1) “[I]t was not sufficiently foreseeable that a pharmacy customer would take the medication in a bottle intended for someone else, notwithstanding that the label listed someone else’s name and a different medication,” and (2) “[T]he Texas legislature has shown itself to be both willing and able to undertake the public policy balancing inherent in extensive regulation of pharmacies’ treatment of prescription drugs.” No. 18-40636 (Aug. 6, 2019).

Nearly a century ago, the unfortunate Helen Palsgraf was injured in a Long Island Railroad station; the difficult tort-law issues arising from her injury continue to challenge the courts today. Martinez v. Walgreens Co. presented the question “whether, under Texas law, a pharmacy owes a duty of care to third parties injured on the road by a customer who was negligently given someone else’s prescription.” The Fifth Circuit answered “no,” considering, inter alia: (1) “[I]t was not sufficiently foreseeable that a pharmacy customer would take the medication in a bottle intended for someone else, notwithstanding that the label listed someone else’s name and a different medication,” and (2) “[T]he Texas legislature has shown itself to be both willing and able to undertake the public policy balancing inherent in extensive regulation of pharmacies’ treatment of prescription drugs.” No. 18-40636 (Aug. 6, 2019).

“Resolving an issue that has brewed for several years in this circuit, we conclude that the TCPA does not apply in diversity cases.” Klocke v. Watson, No. 17-11320 (revised Aug. 29, 2019) (emphasis added). “Because the TCPA imposes evidentiary weighing requirements not found in the Federal Rules, and operates largely without pre-decisional discovery, it conflicts with those rules.”

Assuming the confirmation of Hon. Sul Ozerden of Mississippi, all active-judge positions on the Fifth Circuit will soon be filled. Of the 17 judges, 12 will have been appointed by Republican Presidents (6 by President Trump), and 5 by Democrats. 8 of the 17 judges will have previously served, for some amount of time, as a state or federal trial judge.

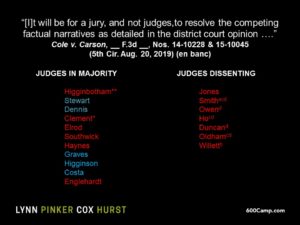

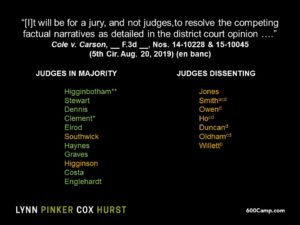

En banc votes by the Court, examined with an eye on the political party of the appointing Presidents, can show patterns. For example, in this week’s Cole v. Carson case, the Democrat-appointed judges voted the same way while the Republican-appointed judges divided. (If these slides are hard to read on your browser, clicking on them should bring them to full size and clear resolution):

All former trial judges voted the same way:

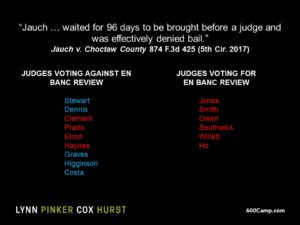

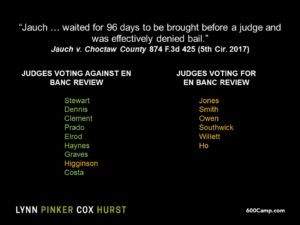

Similarly, in the 2017 case of Jauch v. Choctaw County about pretrial detention, all the Court’s Democrat-appointed judges voted against en banc review, while the Republican-appointed ones divided:

And again, all of the Court’s former trial judges voted the same way:

There are many ways to define, characterize, and otherwise describe judges and their philosophies. This quick review suggests that an exclusive focus on political-party association is too narrow.

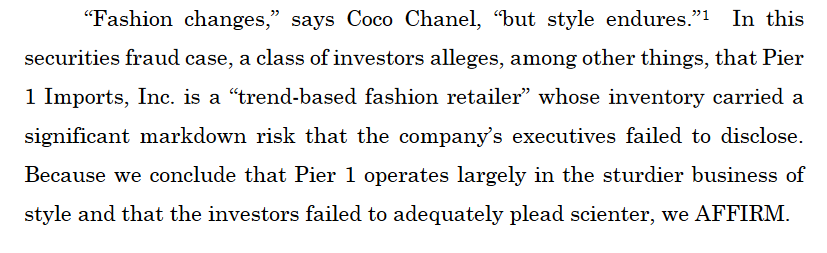

The Fifth Circuit’s published opinions this week include Municipal Employees’ Retirement System v. Pier One Imports, a large securities case involving the beleaguered stock of the “Pier One” retail chain; the second, Cole v. Carson, is a long-running, hard-fought lawsuit about a police shooting. (The fracturing of the en banc court in Cole will be the subject of an upcoming post.) Despite the gravity of these issues, the Court crafted two wonderful turns of phrase, deserving of a moment’s recognition because they are both fun and effective.

The Fifth Circuit’s published opinions this week include Municipal Employees’ Retirement System v. Pier One Imports, a large securities case involving the beleaguered stock of the “Pier One” retail chain; the second, Cole v. Carson, is a long-running, hard-fought lawsuit about a police shooting. (The fracturing of the en banc court in Cole will be the subject of an upcoming post.) Despite the gravity of these issues, the Court crafted two wonderful turns of phrase, deserving of a moment’s recognition because they are both fun and effective.

- The business question giving rise to Pier One was whether management had made wise decisions about what products to emphasize; thus, Judge Elrod began the opinion with some wise words from Coco Chanel:

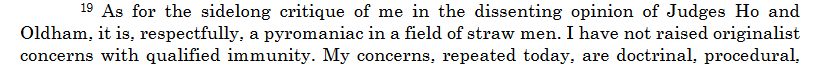

- The dissents in Cole clashed with one another as well as the majority, leading to a “fiery” retort by Judge Willett:

Texas liquor law prohibits a public corporation from holding a “P permit,” which “authorize[s] the sale of liquor, wine, and ale for off-premises consumption.” Wal-Mart successfully challenged this law as a violation of the dormant Commerce Clause.The Fifth Circuit reversed and remanded, making these observations, of general interest beyond this specific dispute, on the issue of legislative intent:

Texas liquor law prohibits a public corporation from holding a “P permit,” which “authorize[s] the sale of liquor, wine, and ale for off-premises consumption.” Wal-Mart successfully challenged this law as a violation of the dormant Commerce Clause.The Fifth Circuit reversed and remanded, making these observations, of general interest beyond this specific dispute, on the issue of legislative intent:

- “Under the law of the Fifth Circuit, evidence that legislators intended to ban potential permittees based on company form alone is insufficient to meet the purpose element of a dormant Commerce Clause claim”;

- “An admission that the drafter sought to create a law that would survive a constitutional challenge is not evidence of a discriminatory legislative purpose”;

- “[O]verreliance on ‘post-enactment testimony’ from actual legislatures is problematic, and not ‘the best indicia of the Texas Legislature’s intent'”; and

- “The motivations and lobbying efforts of the [Texas Package Store are not direct evidence of legislative purpose.”

Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission, No. 18-50299 (Aug. 15, 2019).

A long-litigated dispute about arbitrability reached its latest stage in Archer & White Sales, Inc. v. Henry Schein, Inc., on remand from the Supreme Court, in which the Fifth Circuit held: “The most natural reading of the arbitration clause at issue here states that any dispute, except actions seeking injunctive relief, shall be resolved in arbitration in accordance with the AAA rules. The plain language incorporates the AAA rules—and therefore delegates arbitrability—for all disputes except those under the carve-out. Given that carve-out, we cannot say that the Dealer Agreement evinces a ‘clear and unmistakable’ intent to delegate arbitrability.”

A long-litigated dispute about arbitrability reached its latest stage in Archer & White Sales, Inc. v. Henry Schein, Inc., on remand from the Supreme Court, in which the Fifth Circuit held: “The most natural reading of the arbitration clause at issue here states that any dispute, except actions seeking injunctive relief, shall be resolved in arbitration in accordance with the AAA rules. The plain language incorporates the AAA rules—and therefore delegates arbitrability—for all disputes except those under the carve-out. Given that carve-out, we cannot say that the Dealer Agreement evinces a ‘clear and unmistakable’ intent to delegate arbitrability.”

As for the Supreme Court’s opinion, the panel said: “We are mindful of the Court’s reminder that ‘[w]hen the parties’ contract delegates the arbitrability question to an arbitrator, the courts must respect the parties’ decision as embodied in the contract.’ But we must also heed its warning that ‘courts “should not assume that the parties agreed to arbitrate arbitrability unless there is clear and unmistakable evidence that they did so.’”‘ The parties could have unambiguously delegated this question, but they did not, and we are not empowered to re-write their agreement.” No. 16-41674 (Aug. 16, 2019).

DeJoria v. Maghreb Petroleum Exploration, S.A. presents, at first blush, an epic dispute in which “[t]he facts of this case are littered across the pages of the Federal Reporter.” A failed oil-development project in Morocco led to a $130 million judgment from the Moroccan courts. But after years of legal wrangling about the enforceability of that judgment in Texas, “despite the seeming complexity of this case—royal intrigue, a foreign proceeding, almost a billion dirhams at stake—it ends up being resolved on one of the most basic principles of appellate law: deference to the factfinder.” After confirming the correct legal framework, the Fifth Circuit found no clear error in the district court’s fact-findings. No. 18-50348 (Aug. 16, 2019).

DeJoria v. Maghreb Petroleum Exploration, S.A. presents, at first blush, an epic dispute in which “[t]he facts of this case are littered across the pages of the Federal Reporter.” A failed oil-development project in Morocco led to a $130 million judgment from the Moroccan courts. But after years of legal wrangling about the enforceability of that judgment in Texas, “despite the seeming complexity of this case—royal intrigue, a foreign proceeding, almost a billion dirhams at stake—it ends up being resolved on one of the most basic principles of appellate law: deference to the factfinder.” After confirming the correct legal framework, the Fifth Circuit found no clear error in the district court’s fact-findings. No. 18-50348 (Aug. 16, 2019).

The viability of a tort claim against T-Mobile, arising from delays in obtaining medical treatment, turned on whether this recent statement by the Texas Supreme Court was “obiter dictum” or “judicial dictum”:

Proximate cause requires both cause in fact and foreseeability. For a condition of property to be a cause in fact, the condition must serve as a substantial factor in causing the injury and without which the injury would not have occurred. When a condition or use of property merely furnishes a circumstance that makes the injury possible, the condition or use is not a substantial factor in causing the injury. To be a substantial factor, the condition or use of the property must actually have caused the injury. Thus, the use of property that simply hinders or delays treatment does not actually cause the injury and does not constitute a proximate cause of an injury.

The Fifth Circuit concluded that the statement was judicial dictum entitled to deference in an Erie analysis, and rendered summary judgment for T-Mobile. Alex v. T-Mobile USA, Inc., No. 18-10555 (June 6, 2019, unpublished) (applying City of Dallas v. Sanchez, 494 S.W.3d 722 (Tex. 2016)). (My Pepperdine Law Review article with the University of Idaho’s Wendy Couture remains a strong summary of the underlying theory.)

The complexity of the modern administrative state produces ornate procedural problems – specifically, in Wynnewood Refining Co. v. OSHRC, the challenge of two parties appealing an administrative-agency ruling to two different federal circuit courts. The solution, however, is simple, in the form of a strict “first-to-file” rule established by Congress for this problem: “Th[is] first-to-file rule governs even for petitions filed on the same day; indeed, we have applied it even when petitions were filed within a minute of each other.” The Fifth Circuit rebuffed an attempt by the agency to assert its discretion over which petition was filed first, concluding that Congress had drafted this statute to foreclose precisely such discretion. No. 19-60357 (Aug. 2, 2019).

In Brackeen v. Bernhardt, an opinion of enormous significance to Indian law, the Fifth Circuit found the Indian Child Welfare Act to be constitutional, reversing a district-court opinion that held otherwise. The Court also affirmed various Bureau of Indian Affairs regulations under the Chevron doctrine, noting, inter alia: “The mere fact that an agency interpretation contradicts a prior agency position is not fatal. Sudden and

In Brackeen v. Bernhardt, an opinion of enormous significance to Indian law, the Fifth Circuit found the Indian Child Welfare Act to be constitutional, reversing a district-court opinion that held otherwise. The Court also affirmed various Bureau of Indian Affairs regulations under the Chevron doctrine, noting, inter alia: “The mere fact that an agency interpretation contradicts a prior agency position is not fatal. Sudden and  unexplained change, or change that does not take account of legitimate reliance on prior interpretation, may be arbitrary, capricious [or] an abuse of discretion. But if these pitfalls are avoided, change is not invalidating, since the whole point of Chevron is to leave the discretion provided by the ambiguities of a statute with the implementing agency.” No. 18-11479 (Aug. 9, 2019) (citation omitted). (My colleague Paulette Miniter and I assisted Professor Seth Davis of UC-Berkeley with an amicus brief in this case, in support of the result ultimately reached by the Court.)

unexplained change, or change that does not take account of legitimate reliance on prior interpretation, may be arbitrary, capricious [or] an abuse of discretion. But if these pitfalls are avoided, change is not invalidating, since the whole point of Chevron is to leave the discretion provided by the ambiguities of a statute with the implementing agency.” No. 18-11479 (Aug. 9, 2019) (citation omitted). (My colleague Paulette Miniter and I assisted Professor Seth Davis of UC-Berkeley with an amicus brief in this case, in support of the result ultimately reached by the Court.)

After a five-week trial, three days of deliberation, and an Allen charge, the district court excused Juror No. 7. “[T]he district court found that Juror No. 7 had failed to follow instructions, exhibited a lack of candor during questioning, and had engaged in threatening behavior towards other jurors. Though defendants argue that this juror was removed for reasons that involve the deliberative process, there were sufficient independent reasons for his removal, namely, his lack of candor and his threatening behavior.” The Fifth Circuit followed Circuit precedent that “previously declined to apply the rule used by some circuits that prohibits dismissing a juror unless there is ‘no possibility’ that the failure to deliberate arises from their view of the evidence,” and instead reasons that “when the dismissal is due to a failure to be candid or a refusal to follow instructions, those are grounds that ‘do not implicate the deliberative process.’” United States v. Hodge, No. 17-20720 (Aug. 9, 2019) (applying United States v. Ebron, 683 F.3d 105 (2012)).

After a five-week trial, three days of deliberation, and an Allen charge, the district court excused Juror No. 7. “[T]he district court found that Juror No. 7 had failed to follow instructions, exhibited a lack of candor during questioning, and had engaged in threatening behavior towards other jurors. Though defendants argue that this juror was removed for reasons that involve the deliberative process, there were sufficient independent reasons for his removal, namely, his lack of candor and his threatening behavior.” The Fifth Circuit followed Circuit precedent that “previously declined to apply the rule used by some circuits that prohibits dismissing a juror unless there is ‘no possibility’ that the failure to deliberate arises from their view of the evidence,” and instead reasons that “when the dismissal is due to a failure to be candid or a refusal to follow instructions, those are grounds that ‘do not implicate the deliberative process.’” United States v. Hodge, No. 17-20720 (Aug. 9, 2019) (applying United States v. Ebron, 683 F.3d 105 (2012)).

Warren claimed that an internal investigation report for her employer, Fannie Mae, was defamatory. The Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for the defense, holding, inter alia, that the report was shielded from liability by a qualified privilege. As to Warren’s argument that the report was made with actual malice, her evidence of “things that the investigator left out of the report” did not meet the demanding standard of showing “that the report was false or recklessly disregarded the truth.” And as to her argument about excessive distribution of the report, she “offer[ed] no evidence, other than her own speculation, that any person without a valid interest received the report or was made aware of its findings.” Warren v. Fannie Mae, No. 18-11211 (Aug. 2, 2019).

Warren claimed that an internal investigation report for her employer, Fannie Mae, was defamatory. The Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for the defense, holding, inter alia, that the report was shielded from liability by a qualified privilege. As to Warren’s argument that the report was made with actual malice, her evidence of “things that the investigator left out of the report” did not meet the demanding standard of showing “that the report was false or recklessly disregarded the truth.” And as to her argument about excessive distribution of the report, she “offer[ed] no evidence, other than her own speculation, that any person without a valid interest received the report or was made aware of its findings.” Warren v. Fannie Mae, No. 18-11211 (Aug. 2, 2019).

In a remarkable letter last month, some months after an en banc argument, the federal agency at issue in the high-profile case of Collins v. Mnuchin has decided that it is in fact constitutional. The plaintiffs responded that this position shift proved their point.

In a remarkable letter last month, some months after an en banc argument, the federal agency at issue in the high-profile case of Collins v. Mnuchin has decided that it is in fact constitutional. The plaintiffs responded that this position shift proved their point.

Longoria, a truck driver in Laredo, prevailed in a 3-day jury trial about his injuries arising from an accident, and won judgment for $2.8 million in total, based on the jury’s awards as to nine types of damages. The Fifth Circuit noted these points, among others, in reviewing the defendant’s appeal of that judgment:

Longoria, a truck driver in Laredo, prevailed in a 3-day jury trial about his injuries arising from an accident, and won judgment for $2.8 million in total, based on the jury’s awards as to nine types of damages. The Fifth Circuit noted these points, among others, in reviewing the defendant’s appeal of that judgment:

- Sufficiency v. Excessiveness. “The sufficiency challenge asks only whether there is any evidence for a jury’s award; if there is, the judge’s job is at an end. An excessiveness challenge requires more extensive scrutiny, including—as will be seen—consideration of verdicts in similar cases. And we review the district court’s decision on remittitur only for an abuse of discretion. We cannot assess whether such discretion was abused if the district court was not asked to exercise it in the first instance.”

- Federal v. State. In a review for excessiveness: “The state/federal issue is presented because Texas does not use the maximum recovery rule. It instead conducts a more holistic assessment at both stages of the inquiry.”

- Pain. “This pain is significant. But an award of $1 million is ‘contrary to the overwhelming weight of the evidence,’ given that Longoria can mostly manage the pain by stretching and taking over-the-counter medicine.”

- Anguish. “Longoria points to his fear that he may be unable to keep working as a truck driver. He testified that this occupation is his ‘childhood dream’ and that without it, he could not support his family. But Longoria is cleared to work, and no doctor indicated his ability to work may change in the future. His understandable concern for the future is not the high degree of distress or frequent disruption Texas law requires.”

Longoria v. Hunter Express, No. 17-41042 (Aug. 1, 2019).

Appellants argued that it a securities-registration exemption plainly applied to a transaction; the Fifth Circuit observed: “While the Gleasons now argue that section 4(a)(1)’s applicability is so obvious that the district court committed a clear error of law or manifest injustice, their able lawyers went in a different direction when opposing summary judgment,” and affirmed. Gleason v. Markel Am. Ins. Co, No. 18-40850 (July 30, 2019, unpublished).

Appellants argued that it a securities-registration exemption plainly applied to a transaction; the Fifth Circuit observed: “While the Gleasons now argue that section 4(a)(1)’s applicability is so obvious that the district court committed a clear error of law or manifest injustice, their able lawyers went in a different direction when opposing summary judgment,” and affirmed. Gleason v. Markel Am. Ins. Co, No. 18-40850 (July 30, 2019, unpublished).

Two oft-addressed topics in 2019–the wreckage of Allen Stanford’s Ponzi scheme, and the appropriate deference to district court discretion in c omplex litigation– intersected in Zacarias v. Stanford Int’l Bank, No. 17-11703-CV (July 22, 2019).

omplex litigation– intersected in Zacarias v. Stanford Int’l Bank, No. 17-11703-CV (July 22, 2019).

The panel majority affirmed the “bar orders” entered by the district court in connection with a complicated settlement, observing: “The receiver initiated suit, negotiated, and settled with the Willis Defendants and BMB while empowered to offer global peace, that is, to deal with potential investor holdouts like the Plaintiffs-Objectors. These holdouts have been content for the receiver to pursue litigation for their benefit, then to participate as receivership claimants, collecting pro rata. Now, however, they ask to jump the queue, come what may to their fellow claimants who remain within the receivership distribution process.”

The dissent countered: “I share the majority’s appreciation for this settlement’s practical value. But in my view, the district court lacked jurisdiction to grant the bar orders. The Receiver only had standing to assert the Stanford entities’ claims. It could not release other parties’ claims, or have the court do so, in exchange for a payment to the Stanford estate. For better or worse, the objecting plaintiffs’ claims were beyond the district court’s power.”

“Ordinarily, courts must refrain from interfering with arbitration proceedings. But as our sister circuits have held, and as we now hold today, class arbitration is a ‘gateway’ issue that must be decided by courts, not arbitrators—absent clear and unmistakable language in the arbitration clause to the contrary.” 20/20 Communications, Inc. v. Crawford, No. 1810260 (July 22, 2019).

“Ordinarily, courts must refrain from interfering with arbitration proceedings. But as our sister circuits have held, and as we now hold today, class arbitration is a ‘gateway’ issue that must be decided by courts, not arbitrators—absent clear and unmistakable language in the arbitration clause to the contrary.” 20/20 Communications, Inc. v. Crawford, No. 1810260 (July 22, 2019).

An insurance company drew the Fifth Circuit’s ire (“Only an insurance company could come up with the policy interpretation advanced here”) in a dispute about coverage for a collision caused by drunk driving. The insurer argued “that drunk driving collisions are not ‘accidents,’ because the decision to drink (and then later drive) was intentional—even though there was admittedly no intent to collide with another vehicle. As Cincinnati points out, a jury found that Sanchez intentionally decided to drive while intoxicated, with ‘actual, subjective awareness’ of the ‘extreme degree of risk, considering the probability and magnitude of the potential harm to others.'” The Court found this argument inconsistent with the common meaning of the term “accident,” and further noted that under this reading of the policy: “[A] collision caused by texting while driving would also not be an accident. A collision caused by eating while driving would not be an accident. And a collision caused by doing makeup while driving would not be an accident.” Frederking v. Cincinnati Ins. Co., No. 18-50536 (July 2, 2019).

An insurance company drew the Fifth Circuit’s ire (“Only an insurance company could come up with the policy interpretation advanced here”) in a dispute about coverage for a collision caused by drunk driving. The insurer argued “that drunk driving collisions are not ‘accidents,’ because the decision to drink (and then later drive) was intentional—even though there was admittedly no intent to collide with another vehicle. As Cincinnati points out, a jury found that Sanchez intentionally decided to drive while intoxicated, with ‘actual, subjective awareness’ of the ‘extreme degree of risk, considering the probability and magnitude of the potential harm to others.'” The Court found this argument inconsistent with the common meaning of the term “accident,” and further noted that under this reading of the policy: “[A] collision caused by texting while driving would also not be an accident. A collision caused by eating while driving would not be an accident. And a collision caused by doing makeup while driving would not be an accident.” Frederking v. Cincinnati Ins. Co., No. 18-50536 (July 2, 2019).

The Fifth Circuit denied en banc review of Inclusive Communities v. Lincoln Property Co., 920 F.3d 890 (5th Cir. 2019), which affirmed (over a dissent) the Rule 12 dismissal of Fair Housing Act claims against Dallas-area apartment businesses that declined to participate in the Section 8 program. The votes were as follows:

“Respect for the state system and the strictly circumscribed nature of federal jurisdiction requires our unflagging attention to these limits. We expect the same unflagging attention from litigants who invoke our jurisdiction.” Accordingly, the Fifth Circuit remanded the case of Midcap Media Finance LLC v. Pathway Data, Inc. for further review of diversity jurisdiction. “The parties in this case failed to properly allege diversity of ciizenship. First, the alleged only that Coulter was a California resident, not that he was a California citizen. Second, because MidCap is an LLC, the pleadings needed to identify MidCap’s members and allege their citizenship.” No. 18-50650 (July 9, 2019) (citations omitted).

“Respect for the state system and the strictly circumscribed nature of federal jurisdiction requires our unflagging attention to these limits. We expect the same unflagging attention from litigants who invoke our jurisdiction.” Accordingly, the Fifth Circuit remanded the case of Midcap Media Finance LLC v. Pathway Data, Inc. for further review of diversity jurisdiction. “The parties in this case failed to properly allege diversity of ciizenship. First, the alleged only that Coulter was a California resident, not that he was a California citizen. Second, because MidCap is an LLC, the pleadings needed to identify MidCap’s members and allege their citizenship.” No. 18-50650 (July 9, 2019) (citations omitted).

A concise case study in when a jury may evaluate contractual intent appears in Apache Corp. v. W&T Offshore, No. 7-20599 (July 16, 2019), in which the parties disputed how their Joint Operating Agreement about an offshore drilling project dealt with a $40 million charge associated with using a particular drilling rig.

A concise case study in when a jury may evaluate contractual intent appears in Apache Corp. v. W&T Offshore, No. 7-20599 (July 16, 2019), in which the parties disputed how their Joint Operating Agreement about an offshore drilling project dealt with a $40 million charge associated with using a particular drilling rig.

On the one hand, section 6.2 said that the operator “shall not make any single expenditure . . . costing $200,000 or more” unless an Authorization for Expenditure (“AFE”) is approved. A related provision, about accounting, says that an “acceptable reason[] for non-payment or short payment” includes the situation “when an AFE is not approved.” The defendant cited these provisions in declining to pay, arguing that it had not an AFE on the subject of the rig.

But the operator cited section 18.4, which addresses government-mandated plugging & abandonment operations, and said that the operator “[s]hall conduct” such activity as “required by a governmental authority,” with “the Costs, risks and net proceeds . . . shared by the Participating Parties in such well . . . .” It argued that the rig was necessary to carry  out such activity.

out such activity.

The Fifth Circuit agreed with the district court that “[a]pplying Section 6.2’s expenditure provision to a government-mandated P&A undertaken pursuant to Section 18.4 would lead to an absurd consequence: namely a situation is empowered to hold an operator hostage, preventing the operator from completing a legally required P&A, in order to extract a better bargain or avoid cost-sharing altogether.” Accordingly, whether section 6.2 applied to a section 18.4 undertaking “is ambiguous and was properly put to the jury.”

Tow v. Organo Gold Int’l presented a challenge, in a trade-secrets case, to a damages model based on “avoided costs” rather than “lost profits.” Specifically: “Weingust [Plaintiff’s expert] concluded that the distributor network was worth approximately $3.451 million based on the following two methodologies: the cost approach showed AmeriSciences had incurred about $6.2 million over five years to develop the distributor network, attract new distributors, and retain existing ones. The income approach considers how long income is expected from the asset and the amount of income each year. Weingust concluded the income approach dictated the network would generate $700,327 over ten years. Weingust testified that neither valuation method was better than the other, so he averaged the two to conclude the value of the distributor network was $3.451 million.” This model was consistent with – indeed, expressly allowed by – GlobeRanger Corp. v. Software AG, 836 F.3d 477, 499 (5th Cir. 2016). No. 18-20394 (July 11, 2019).

Tow v. Organo Gold Int’l presented a challenge, in a trade-secrets case, to a damages model based on “avoided costs” rather than “lost profits.” Specifically: “Weingust [Plaintiff’s expert] concluded that the distributor network was worth approximately $3.451 million based on the following two methodologies: the cost approach showed AmeriSciences had incurred about $6.2 million over five years to develop the distributor network, attract new distributors, and retain existing ones. The income approach considers how long income is expected from the asset and the amount of income each year. Weingust concluded the income approach dictated the network would generate $700,327 over ten years. Weingust testified that neither valuation method was better than the other, so he averaged the two to conclude the value of the distributor network was $3.451 million.” This model was consistent with – indeed, expressly allowed by – GlobeRanger Corp. v. Software AG, 836 F.3d 477, 499 (5th Cir. 2016). No. 18-20394 (July 11, 2019).

After a recent en banc vote, the full Fifth Circuit will engage an important limit on the power of the administrative state. The majority and dissenting opinons in Sierra Club v. Luminant Energy grappled with the “concurrent-remedies doctrine” and whether it created a limitations bar to an action for equitable relief under the Clean Air Act. No. No. 17-10235 (order issued June 10, 2019).

After a recent en banc vote, the full Fifth Circuit will engage an important limit on the power of the administrative state. The majority and dissenting opinons in Sierra Club v. Luminant Energy grappled with the “concurrent-remedies doctrine” and whether it created a limitations bar to an action for equitable relief under the Clean Air Act. No. No. 17-10235 (order issued June 10, 2019).

Hard-fought litigation about reform to Texas’s foster-care system led to an injunction, an appeal, a limited remand to revise the injunction, and a renewed appeal. The panel majority affirmed in part and reversed in part, finding, inter alia: (i) the revised injunction exceeded the mandate of the limited remand; (ii) that a requirement affirmed in the appeal was, upon further review, in fact unnecessary; and (iii) that a provision about data use required additional confidentiality safeguards.

Hard-fought litigation about reform to Texas’s foster-care system led to an injunction, an appeal, a limited remand to revise the injunction, and a renewed appeal. The panel majority affirmed in part and reversed in part, finding, inter alia: (i) the revised injunction exceeded the mandate of the limited remand; (ii) that a requirement affirmed in the appeal was, upon further review, in fact unnecessary; and (iii) that a provision about data use required additional confidentiality safeguards.

A strong dissent protested the overall lack of deference to the district court’s discretion, focusing in particular on a provision about “an integrated computer system to rationalize record keeping.” It argued that by vacating that provision, “the majority completes its walk away from the district court’s interlaced remedial scheme, taking away provisions essential to its success . . . a decision flawed by the evidence and controlling legal principles.” The dissent further observed: “[The State’s] reflexive resistance to the federal district court’s remedial orders–both direct confrontation and a refusal to cooperate or otherwise participate in the crafting of a response–bespeaks a view of our federalism inverted to look past the unchallenged finding of this court of the State’s deliberate indifference to the constitutional rights of PMC children . . . .” M.D. v. Abbott, No. 18-40057 (July 8, 2019).

“The complaint alleges that during the April and October 2016 phone calls, the defendants negligently misrepresented to Mr. Dick that ‘reinstatement was not an option’ and that ‘there was nothing [the] Plaintiff could do to stop a foreclosure.’ The plaintiff’s claim that these misrepresentations prevented her from reinstating the loan merely repackages her claim for breach of contract based on the duty to cooperate. It is therefore barred by the economic loss rule.” Dick v. Colorado Housing Enterprises LLC, No. 18-10900 (July 5, 2019) (unpublished).

“The complaint alleges that during the April and October 2016 phone calls, the defendants negligently misrepresented to Mr. Dick that ‘reinstatement was not an option’ and that ‘there was nothing [the] Plaintiff could do to stop a foreclosure.’ The plaintiff’s claim that these misrepresentations prevented her from reinstating the loan merely repackages her claim for breach of contract based on the duty to cooperate. It is therefore barred by the economic loss rule.” Dick v. Colorado Housing Enterprises LLC, No. 18-10900 (July 5, 2019) (unpublished).