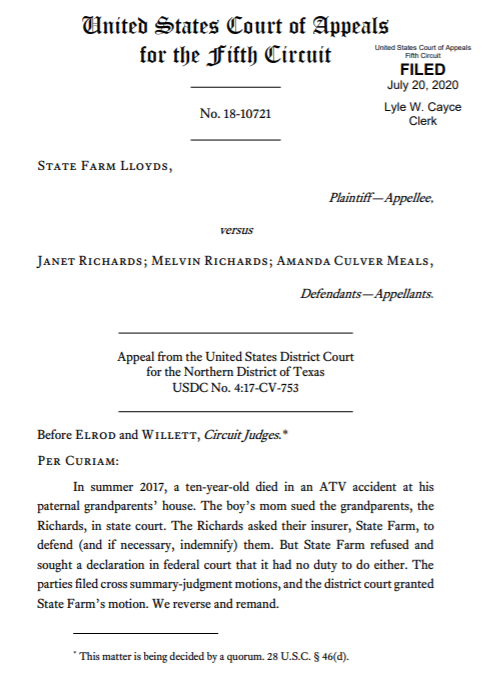

In Six Dimensions, Inc. v. Perficient, Inc., the Fifth Circuit concluded that under California noncompete law, the parties’ “2014 Agreement” was unenforceable. A key question was whether their “2015 Agreement” was also subject to that conclusion, or whether it was separate and the arguments against it had been waived in the trial court. The Court found no waiver, concluding that the below language was insufficient notice that the plaintiff was seeking summary judgment about that contract.

In Six Dimensions, Inc. v. Perficient, Inc., the Fifth Circuit concluded that under California noncompete law, the parties’ “2014 Agreement” was unenforceable. A key question was whether their “2015 Agreement” was also subject to that conclusion, or whether it was separate and the arguments against it had been waived in the trial court. The Court found no waiver, concluding that the below language was insufficient notice that the plaintiff was seeking summary judgment about that contract.

“Defendant argues that Brading was permitted to engage in this wrongful conduct because the contract that she signed, contained a provision that is not allowed under California law. Defendant argues that even though the Amended Complaint does not accuse Brading of breaching the non-competition portion of the 2014 Agreement [Dkt 10-2], that its presence in the 2014 Agreement invalidates that agreement. Texas has no such provision. It is respectfully submitted, as asserted in the Complaint, that the law of Texas applies and as such, the 2014 Agreement is clearly breached by Brading’s undisputed conduct in violating both portions of the 2014 Agreement. Further, there is no noncompetition portion for the Termination Certification signed by Brading in June of 2015 and as such, under the law of either State, Brading is responsible for violating the 2015 Agreement.”

No. 19-20505 (Aug. 7, 2020) (emphasis added).