The once-obscure Court of International Trade – once an Article I tribunal, but “promoted” to Article III status in 1956 – took issue with the legal basis for many of the Trump Administration’s tariffs.

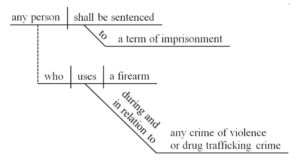

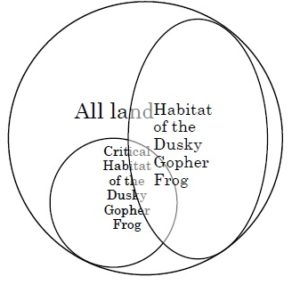

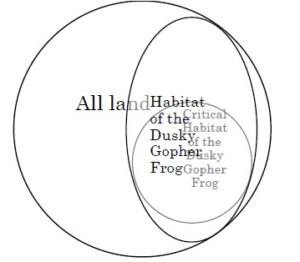

Specifically, in V.O.S. Selections, Inc. v. United States, that court held that the International Emergency Economic Powers Act’s authorization for the President to “regulate . . . importation” does not confer unbounded tariff authority: “[T]his court reads ‘regulate . . . importation’ to provide more limited authority so as to avoid constitutional infirmities and maintain the ‘separate and distinct exercise of the different powers of government’ that is ‘essential to the preservation of liberty.'”

The opinion went on to distinguish between the President’s emergency powers and more narrowly tailored statutory authorities, such as those found in the Trade Act of 1974, which specifically limit the President’s ability to impose tariffs in response to trade deficits or other economic concerns. Nos. 25-00066 & 25-00077, May 28, 2025