The Fifth Circuit reversed the dismissal of a securities claim against Six Flags involving its public statements about an expansion effort in China, concluding that as to some of the challenged statements, the plaintiff had satisfied the PSLRA’s demanding requirements. Oklahoma Firefighters Pension & Retirement System v. Six Flags Entertainment Corp., No. 21-10865 (Jan. 18, 2022). The opinion provides detailed discussion of just is required to adequately plead falsity and scienter, especially in the context of forward-looking statements. It also provides what appears to be the first reference in the Federal Reporter to vexillology (the study of flags):

Category Archives: Securities

In a change from the constitutional issues that have plagued the SEC in court of late, in SEC v. World Tree Financial, LLC, the Fifth Circuit affirmed a securities-fraud judgment based on “a fraudulent ‘cherry-picking’ scheme, in which [defendants] allocated favorable trades to themselves and favored clients and unfavorable trades to disfavored clients.” Proof of this scheme required sophisticated statistical analysis, summarized as follows:

In a change from the constitutional issues that have plagued the SEC in court of late, in SEC v. World Tree Financial, LLC, the Fifth Circuit affirmed a securities-fraud judgment based on “a fraudulent ‘cherry-picking’ scheme, in which [defendants] allocated favorable trades to themselves and favored clients and unfavorable trades to disfavored clients.” Proof of this scheme required sophisticated statistical analysis, summarized as follows:

To analyze World Tree’s allocation data, [the SEC’s expert] divided the client accounts into three categories: (1) accounts controlled by Perkins, Gilmore, or both (“Favored-Perkins accounts”); (2) accounts owned by World Tree clients other than Matthew LeBlanc and his business Delcambre Cellular (“Favored-Client accounts”); and (3) accounts owned by LeBlanc and Delcambre (“Disfavored accounts”). She then measured several performance measures and subsets of trades: most and least profitable trades, day trades, average first-day returns, earnings-day trades, overlapping stocks, and trades after LeBlanc complained to Perkins about his accounts’ poor performance. According to her analysis, from July 2012 to July 2015, Perkins methodically allocated trades with favorable first-day returns to the FavoredPerkins and Favored-Client accounts, while allocating trades with unfavorable first-day returns to the Disfavored accounts.

[She] opined that the “evidence overwhelmingly indicates that Perkins engaged in cherry-picking.” Though she acknowledged at trial that the data reflected only a pattern and that she did not “have the ability to identify individual trades that may or may not be improper,” the data in the aggregate showed a “one in one million chance that these patterns could have occurred if allocations were being made without regard to first-day return.”

No. 21-30063 (Aug. 4, 2022).

A sweeping analysis of different types of disgorgement led to this conclusion about the securities laws in SEC v. Hallam: “[W]e conclude that Sections 78u(d)(3) and (d)(7) authorize legal ‘disgorgement’ apart from the equitable ‘disgorgement’ permitted by Liu. That answers the question which ‘soil,’ came with the ‘term of art,’ that Congress used.” No. 21-10222 (July 19, 2022) (citations omitted). While focused on a precise issue about the most recent amendments to federal securities law, Hallam offers a detailed history and summary of approaches to disgorgement of ill-gotten gains, in both law and equity.

A sweeping analysis of different types of disgorgement led to this conclusion about the securities laws in SEC v. Hallam: “[W]e conclude that Sections 78u(d)(3) and (d)(7) authorize legal ‘disgorgement’ apart from the equitable ‘disgorgement’ permitted by Liu. That answers the question which ‘soil,’ came with the ‘term of art,’ that Congress used.” No. 21-10222 (July 19, 2022) (citations omitted). While focused on a precise issue about the most recent amendments to federal securities law, Hallam offers a detailed history and summary of approaches to disgorgement of ill-gotten gains, in both law and equity.

In the movie “Girls! Girls! Girls!” Elvis  Presley enthusiastically sang “Return to Sender.” In that general spirit, the Fifth Circuit affirmed a disgorgement award in SEC v. Blackburn when “[f]irst, the disgorgement amounts are the profits defendants received from their securities fraud,” and “[s]econd, the district court concluded that the SEC has identified the victims and created a process for the return of disgorged funds” to the victims. (emphasis added). In so doing, the SEC avoided the “the issue [Liu v. SEC, 140 S. Ct. 1936 (2020)] left open: whether

Presley enthusiastically sang “Return to Sender.” In that general spirit, the Fifth Circuit affirmed a disgorgement award in SEC v. Blackburn when “[f]irst, the disgorgement amounts are the profits defendants received from their securities fraud,” and “[s]econd, the district court concluded that the SEC has identified the victims and created a process for the return of disgorged funds” to the victims. (emphasis added). In so doing, the SEC avoided the “the issue [Liu v. SEC, 140 S. Ct. 1936 (2020)] left open: whether

disgorgement is ‘awarded for victims’ when the money is put into a

Treasury fund that helps “pay whistleblowers reporting securities fraud and

to fund the activities of the Inspector General.” No. 20-30464 (Oct. 12, 2021).

While applying a Louisiana statute, the Fifth Circuit reviewed federal securities law in Firefighters’ Retirement System v. Citco Group Ltd. and concluded that the defendants were not “control persons.” The substantive issue involved “material omissions from [an] offering memorandum”; thus, “to establish that the [defendants] were control persons, the pension plans must show that they had the ability to control the content of the offering memorandum.” The Court noted evidence that (a) the defendants “provided back-office administrative services” to the company at issue and could have stopped providing those services, (b) had made a loan that could have been called, and (c) “held … voting shares for administrative convenience” in a relevant entity, and found this evidence insufficient. No. 20-30654 (March 31, 2021).

While applying a Louisiana statute, the Fifth Circuit reviewed federal securities law in Firefighters’ Retirement System v. Citco Group Ltd. and concluded that the defendants were not “control persons.” The substantive issue involved “material omissions from [an] offering memorandum”; thus, “to establish that the [defendants] were control persons, the pension plans must show that they had the ability to control the content of the offering memorandum.” The Court noted evidence that (a) the defendants “provided back-office administrative services” to the company at issue and could have stopped providing those services, (b) had made a loan that could have been called, and (c) “held … voting shares for administrative convenience” in a relevant entity, and found this evidence insufficient. No. 20-30654 (March 31, 2021).

The Fifth Circuit affirmed a summary judgment in favor of a business that had been accused of being a “control person” under Louisiana securities laws. “As the district court recognized, the contract between STC and SEI is strong evidence that SEI was unable to control STC’s primary violations. The contract made STC responsible for pricing the SIBL CDs and for providing accurate information to SEI. The contract does not assign any role to SEI in the sale or valuation of SIBL CDs. Further, as the district court noted, the investors’ ‘pleadings contain no evidence demonstrating that the relationship between the companies differed from that contemplated in the

The Fifth Circuit affirmed a summary judgment in favor of a business that had been accused of being a “control person” under Louisiana securities laws. “As the district court recognized, the contract between STC and SEI is strong evidence that SEI was unable to control STC’s primary violations. The contract made STC responsible for pricing the SIBL CDs and for providing accurate information to SEI. The contract does not assign any role to SEI in the sale or valuation of SIBL CDs. Further, as the district court noted, the investors’ ‘pleadings contain no evidence demonstrating that the relationship between the companies differed from that contemplated in the

contract.'” The Court then reviewed, and rejected, evidence about the types of work done by the defendant as a service provider. Ahders v. SEI Private Trust Co., No. 20-30186 (Dec. 3, 2020).

“Appellants argue that, by finding disgorgement a ‘penalty’ under [28] § 2462, Kokesh necessarily also decided that disgorgement is not an equitable remedy courts may impose in SEC enforcement proceedings. We disagree. Kokesh itself expressly declined to address that question, and so our precedent upholding district court authority to order disgorgement controls.” SEC v. Team Resources Inc., No. 18-10931 (Nov. 5, 2019).

“Appellants argue that, by finding disgorgement a ‘penalty’ under [28] § 2462, Kokesh necessarily also decided that disgorgement is not an equitable remedy courts may impose in SEC enforcement proceedings. We disagree. Kokesh itself expressly declined to address that question, and so our precedent upholding district court authority to order disgorgement controls.” SEC v. Team Resources Inc., No. 18-10931 (Nov. 5, 2019).

A securities-fraud class action lived to fight another day in Broyles v. Commonwealth Advisors: “The district court erred in deciding that plaintiffs lacked standing under Delaware law to bring a direct action against their investment advisers rather than initiating a derivative action in behalf of the hedge funds that the advisers had assembled and managed for fraudulent inducement purposes. The investor plaintiffs adequately supported their motion for partial summary judgment demonstrating their Article III standing with appropriate evidence of their injury-in-fact that arose :immediately upon their purchase of the falsely overvalued securities; were induced and caused by the defendant advisers’ fraudulent advice and solicitations; and likely will be redressed by a favorable decision on the merits.” No. 17-30092 (Aug. 28, 2019).

A securities-fraud class action lived to fight another day in Broyles v. Commonwealth Advisors: “The district court erred in deciding that plaintiffs lacked standing under Delaware law to bring a direct action against their investment advisers rather than initiating a derivative action in behalf of the hedge funds that the advisers had assembled and managed for fraudulent inducement purposes. The investor plaintiffs adequately supported their motion for partial summary judgment demonstrating their Article III standing with appropriate evidence of their injury-in-fact that arose :immediately upon their purchase of the falsely overvalued securities; were induced and caused by the defendant advisers’ fraudulent advice and solicitations; and likely will be redressed by a favorable decision on the merits.” No. 17-30092 (Aug. 28, 2019).

The Fifth Circuit revised its original opinion in SEC v. Arcturus Corp., reaching the same result (reversal of a summary judgment for the SEC about whether certain investment contracts were securities), while adding significant factual and legal detail about the sophistication of the relevant investors – the issue on which the Court found summary judgment to have been inappropriate. SEC v. Arcturus Corp. (revised), No. 17-10503.

The Fifth Circuit revised its original opinion in SEC v. Arcturus Corp., reaching the same result (reversal of a summary judgment for the SEC about whether certain investment contracts were securities), while adding significant factual and legal detail about the sophistication of the relevant investors – the issue on which the Court found summary judgment to have been inappropriate. SEC v. Arcturus Corp. (revised), No. 17-10503.

In SEC v. Stanford Int’l Bank, Ltd., the Fifth Circuit reviewed an intricate, court-supervised settlement between the receiver for Stanford International Bank and several D&O carriers, and “conclude[d] the district court lacked authority to approve the Receiver’s settlement to the extent it (a) nullified the coinsureds’ claims to the policy proceeds without an alternative compensation scheme; (b) released claims the Estate did not possess; and (c) barred suits that could not result in judgments against proceeds of the Underwriters’ policies or other receivership assets.”

In SEC v. Stanford Int’l Bank, Ltd., the Fifth Circuit reviewed an intricate, court-supervised settlement between the receiver for Stanford International Bank and several D&O carriers, and “conclude[d] the district court lacked authority to approve the Receiver’s settlement to the extent it (a) nullified the coinsureds’ claims to the policy proceeds without an alternative compensation scheme; (b) released claims the Estate did not possess; and (c) barred suits that could not result in judgments against proceeds of the Underwriters’ policies or other receivership assets.”

The Court observed: “By ignoring the distinction between Appellants’ contractual and extracontractual claims against Underwriters, the district court erred legally and abused its discretion in approving the bar orders. These claims . . . lie directly against the Underwriters and do not involve proceeds from the insurance policies or other receivership assets. . . . [R]eceivership courts have no authority to dismiss claims that are unrelated to the receivership estate. That the district court was ‘looking only to the fairness of the settlement as between the debtor and the settling claimant [and ignoring third-party rights] contravenes a basic notion of fairness.'” No. 17-10663 (June 17, 2019).

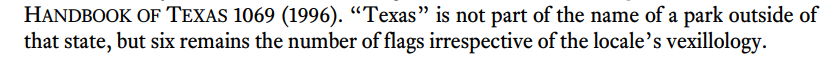

Life Partners’ Creditors’ Trust v. Cowley, No. 17-11477 (May 31, 2019), reviewed the dismissal of several highly-technical claims brought by a bankruptcy trustee about the sale of “viaticals” (investments in life insurance policies sold to third parties by the insureds). For each claim, the Fifth Circuit reviewed whether FRCP 9(b) or 8(a) applied, and then assessed the pleaded allegations, reaching these conclusions:

A remarkably long-lived case about the collapse of Enron came to an end in Lampkin v. UBS Fin. Servs., Inc.: “[Plaintiffs[‘] Securities Act claims fail because their participation in the Employee Stock Option Plan was compulsory and employees furnished no value, or tangible and definable consideration in exchange for the option grants. The Court in [Int’ Brotherhood of Teamsters v. Daniel, 439 U.S. 551 (1979)] rejected the idea that the exchange of labor was sufficient consideration in the context of a compulsory, non-contributory pension plan—the same logic applies to the option plan at issue here. Plaintiffs made no investment decision in the grant of the options, the Enron plans were compulsory and non-contributory. The fact that plaintiffs would eventually make an affirmative investment decision—whether to exercise the option or let it expire—at some point in the future is of no consequence. Plaintiffs’ claims are based explicitly on the grant of the option, not the exercise of that option.” No. 17-20608 (May 24, 2019) (emphasis added).

A remarkably long-lived case about the collapse of Enron came to an end in Lampkin v. UBS Fin. Servs., Inc.: “[Plaintiffs[‘] Securities Act claims fail because their participation in the Employee Stock Option Plan was compulsory and employees furnished no value, or tangible and definable consideration in exchange for the option grants. The Court in [Int’ Brotherhood of Teamsters v. Daniel, 439 U.S. 551 (1979)] rejected the idea that the exchange of labor was sufficient consideration in the context of a compulsory, non-contributory pension plan—the same logic applies to the option plan at issue here. Plaintiffs made no investment decision in the grant of the options, the Enron plans were compulsory and non-contributory. The fact that plaintiffs would eventually make an affirmative investment decision—whether to exercise the option or let it expire—at some point in the future is of no consequence. Plaintiffs’ claims are based explicitly on the grant of the option, not the exercise of that option.” No. 17-20608 (May 24, 2019) (emphasis added).

Alaska Electrical Pension Fund v. Flotek Industries shows how demanding the federal securities laws are as to the issue of “scienter,” The plaintiffs alleged misrepresentations by the defendant about the viability of its software product called “FracMax,” which analyzes data about hydraulically-fractured oil and gas wells. These four alleged misrepresentations were not sufficient to produce the required “strong inference of scienter:

Alaska Electrical Pension Fund v. Flotek Industries shows how demanding the federal securities laws are as to the issue of “scienter,” The plaintiffs alleged misrepresentations by the defendant about the viability of its software product called “FracMax,” which analyzes data about hydraulically-fractured oil and gas wells. These four alleged misrepresentations were not sufficient to produce the required “strong inference of scienter:

- “Defendants’ repeated use of the term “conclusive” in describing FracMax’s effect, which Plaintiffs characterize as tantamount to assuring that FracMax’s data was irrefutable”;

- “Defendants’ reference to FracMax data as “unadjusted” when, in fact, FracMax used an algorithm to adjust certain data”;

- “Defendant Chisholm [the CEO]’s presentation at the September 11, 2015, conference of direct comparisons between several wells that used CnF [a technology measured by FracMax] versus several that did not, which Defendants concede relied on incorrect data for the non-CnF wells”; and

- “Chisholm’s representation at this same conference that this data was ‘back check[ed] and validate[d],’ when Defendants later admitted that ‘Flotek had no internal controls in place to ensure the integrity of the FracMax database.'”

No. 17-20308 (Feb. 7, 2019).

In a counterpoint to last month’s decision in SEC v. Sethi, the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment about whether oil-and-gas investment contracts qualified as “securities” for purposes of 10(b)(5) and 15(a) liability: “Fifteen investors also submitted affidavits declaring that they had the power to, and did in fact, vote on a variety of decisions. And the record does not show that Arcturus or Aschere took any significant actions without the investors’ prior approval. The fact that the investors voted and took actions to manage the drilling projects makes this case different than others where the district court appropriately granted summary judgment.” SEC v. Arcturus Corp., No. 17-10503 (Jan. 7, 2019).

In a counterpoint to last month’s decision in SEC v. Sethi, the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment about whether oil-and-gas investment contracts qualified as “securities” for purposes of 10(b)(5) and 15(a) liability: “Fifteen investors also submitted affidavits declaring that they had the power to, and did in fact, vote on a variety of decisions. And the record does not show that Arcturus or Aschere took any significant actions without the investors’ prior approval. The fact that the investors voted and took actions to manage the drilling projects makes this case different than others where the district court appropriately granted summary judgment.” SEC v. Arcturus Corp., No. 17-10503 (Jan. 7, 2019).

“Sethi sold in terests in an oil and gas joint venture.” The SEC then sued Sethi for selling unregistered securities, and the Fifth Circuit agreed with the SEC’s position that the joint venture interests at issue qualified as securities under federal law. That legal analysis turned on a 3-part test for whether an investment contract is a security: “(1) an investment of money; (2) in a common enterprise; and (3) on an expectation of profits to be derived solely from the efforts of individuals other than the investor,” followed by a flexible, multi-factor analysis of the term “solely,” designed “to ensure that the securities laws are not easily circumvented by agreements requiring a ‘modicum of effort’ on the part of investors.” SEC v. Sethi, No. 17-41022 (Dec. 4, 2018) (applying, inter alia, Williamson v. Tucker, 645 F.2d 404 (5th Cir. 1981)).

terests in an oil and gas joint venture.” The SEC then sued Sethi for selling unregistered securities, and the Fifth Circuit agreed with the SEC’s position that the joint venture interests at issue qualified as securities under federal law. That legal analysis turned on a 3-part test for whether an investment contract is a security: “(1) an investment of money; (2) in a common enterprise; and (3) on an expectation of profits to be derived solely from the efforts of individuals other than the investor,” followed by a flexible, multi-factor analysis of the term “solely,” designed “to ensure that the securities laws are not easily circumvented by agreements requiring a ‘modicum of effort’ on the part of investors.” SEC v. Sethi, No. 17-41022 (Dec. 4, 2018) (applying, inter alia, Williamson v. Tucker, 645 F.2d 404 (5th Cir. 1981)).

Whole Foods admitted to mislabeling certain prepackaged foods, which in addition to other legal problems, drew a securities fraud claim. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the rejection of that claim, observing: “The relationship between the weights-and-measures fraud and the plaintiffs’ loss (the decline in the stock price) is causal; the relationship between the alleged securities fraud and the plaintiffs’ loss is spurious. Whole Foods’ overcharging caused (1) the alleged accounting problems and (2) the public-relations problems. The public-relations problems arguably led to slowed sales and the loss in stock price. But the accounting problems did not cause the public-relations problem, nor do the plaintiffs allege that the accounting problems caused a separate loss in stock price.” Employers’ Retirement System v. Whole Foods Market, No. 17-50840 (Oct. 3, 2018).

Whole Foods admitted to mislabeling certain prepackaged foods, which in addition to other legal problems, drew a securities fraud claim. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the rejection of that claim, observing: “The relationship between the weights-and-measures fraud and the plaintiffs’ loss (the decline in the stock price) is causal; the relationship between the alleged securities fraud and the plaintiffs’ loss is spurious. Whole Foods’ overcharging caused (1) the alleged accounting problems and (2) the public-relations problems. The public-relations problems arguably led to slowed sales and the loss in stock price. But the accounting problems did not cause the public-relations problem, nor do the plaintiffs allege that the accounting problems caused a separate loss in stock price.” Employers’ Retirement System v. Whole Foods Market, No. 17-50840 (Oct. 3, 2018).

The plaintiffs in Alaska Elec. Pension Fund v. Asar alleged securities fraud about the affairs of Hanger, Inc., the nation’s largest provider of orthotic and prosthetic patient care. The Fifth Circuit largely affirmed dismissal, but as to one defendant found adequate allegations of scienter based primarily on statements in an audit committee report, which “support the inference that McHenry shared the objectives of improperly enhancing Hanger’s financial results, or that he at least knew that others were doing so. A dissent would have also dismissed as to him, noting that “the complaint makes no effort to demonstrate which portions of the Report show that McHenry, or any other defendant, had the requisite scienter.” No. 17-50162 (Aug. 6, 2018).

The plaintiffs in Alaska Elec. Pension Fund v. Asar alleged securities fraud about the affairs of Hanger, Inc., the nation’s largest provider of orthotic and prosthetic patient care. The Fifth Circuit largely affirmed dismissal, but as to one defendant found adequate allegations of scienter based primarily on statements in an audit committee report, which “support the inference that McHenry shared the objectives of improperly enhancing Hanger’s financial results, or that he at least knew that others were doing so. A dissent would have also dismissed as to him, noting that “the complaint makes no effort to demonstrate which portions of the Report show that McHenry, or any other defendant, had the requisite scienter.” No. 17-50162 (Aug. 6, 2018).

In a seemingly immortal case about the failure of Enron,  Plaintiffs sought to characterize several UBS business entities as one. The Fifth Circuit rejected this argument under the applicable Delaware test for a joint venture: “Plaintiffs fail to explain how the allegations identified in their brief on appeal support finding a joint venture under this test. None of the allegations allude to profit sharing, or loss sharing, right to control the purported joint venture.” (citations omitted). “Plaintiffs’ allegations—principally references to Defendants’ vague corporate platitudes about their integration as a firm—may logically support that Defendants shared a community of interest in their business activities, but this alone is insufficient to support joint venture liability.” Giancarlo v. UBS Fin. Servcs., No. 16-20663 (Feb. 26, 2018).

Plaintiffs sought to characterize several UBS business entities as one. The Fifth Circuit rejected this argument under the applicable Delaware test for a joint venture: “Plaintiffs fail to explain how the allegations identified in their brief on appeal support finding a joint venture under this test. None of the allegations allude to profit sharing, or loss sharing, right to control the purported joint venture.” (citations omitted). “Plaintiffs’ allegations—principally references to Defendants’ vague corporate platitudes about their integration as a firm—may logically support that Defendants shared a community of interest in their business activities, but this alone is insufficient to support joint venture liability.” Giancarlo v. UBS Fin. Servcs., No. 16-20663 (Feb. 26, 2018).

Plaintiffs sued under ERISA about the handling of company stock in RadioShack employees’ 401K plans. The Fifth Circuit affirmed dismissal. As to the claims based on ERISA’s duty of prudence, the Court reminded: “Dudenoeffer establishes that for publicly-traded stocks, ‘allegations that a fiduciary should have recognized from publicly available information alone that the market was over- or undervaluing the stock are implausible as a general rule, at least in the absence of special circumstances.'” Here: “Plaintiffs argue

Plaintiffs sued under ERISA about the handling of company stock in RadioShack employees’ 401K plans. The Fifth Circuit affirmed dismissal. As to the claims based on ERISA’s duty of prudence, the Court reminded: “Dudenoeffer establishes that for publicly-traded stocks, ‘allegations that a fiduciary should have recognized from publicly available information alone that the market was over- or undervaluing the stock are implausible as a general rule, at least in the absence of special circumstances.'” Here: “Plaintiffs argue  that Dudenhoeffer addressses only allegations that public information showed that a stock was overvalued, not claims that the stock was excessively risky. This distinction between claims that stock is overvalued and claims that stock is excessively risky is ‘illusory.’ In an efficient market, market price accounts for risk. Plan fiduciaries cannot be expected to outperform the market or predict future stock performance using publicly available information.” Singh v. RadioShack Corp., 882 F.3d 137 (5th Cir. 2018) (applying Fifth Third Bancorp v. Dudenhoeffer, 134 S. Ct. 2459 (2014)).

that Dudenhoeffer addressses only allegations that public information showed that a stock was overvalued, not claims that the stock was excessively risky. This distinction between claims that stock is overvalued and claims that stock is excessively risky is ‘illusory.’ In an efficient market, market price accounts for risk. Plan fiduciaries cannot be expected to outperform the market or predict future stock performance using publicly available information.” Singh v. RadioShack Corp., 882 F.3d 137 (5th Cir. 2018) (applying Fifth Third Bancorp v. Dudenhoeffer, 134 S. Ct. 2459 (2014)).

ERISA litigation about investment management presents a tension between the administrators’ fiduciary obligations, on the one hand, and discouraging needless litigation, on the other. After the Supreme Court’s most recent guidance about an ERISA fiduciary’s “duty of prudence” in Amgen Inc. v. Harris, 136 S. Ct. 758 (2016), the Fifth Circuit found that the plaintiffs in Whitley v. BP. PLC failed to meet their pleading burden: “The amended complaint states that BP’s stock was overvalued prior to the Deepwater Horizon explosion due to “numerous undisclosed safety breaches” known only to insiders. In other words, the stockholders theorize that BP stock was overpriced because BP had a greater risk exposure to potential accidents than was known to the market. Based on this fact alone, it does not seem reasonable to say that a prudent fiduciary at that time could not have concluded that (1) disclosure of such information to the public or (2) freezing trades of BP stock—both of which would likely lower the stock price—would do more harm than good. In fact, it seems that a prudent fiduciary could very easily conclude that such actions would do more harm than good.” No. 15-20282 (Sept. 26, 2016).

ERISA litigation about investment management presents a tension between the administrators’ fiduciary obligations, on the one hand, and discouraging needless litigation, on the other. After the Supreme Court’s most recent guidance about an ERISA fiduciary’s “duty of prudence” in Amgen Inc. v. Harris, 136 S. Ct. 758 (2016), the Fifth Circuit found that the plaintiffs in Whitley v. BP. PLC failed to meet their pleading burden: “The amended complaint states that BP’s stock was overvalued prior to the Deepwater Horizon explosion due to “numerous undisclosed safety breaches” known only to insiders. In other words, the stockholders theorize that BP stock was overpriced because BP had a greater risk exposure to potential accidents than was known to the market. Based on this fact alone, it does not seem reasonable to say that a prudent fiduciary at that time could not have concluded that (1) disclosure of such information to the public or (2) freezing trades of BP stock—both of which would likely lower the stock price—would do more harm than good. In fact, it seems that a prudent fiduciary could very easily conclude that such actions would do more harm than good.” No. 15-20282 (Sept. 26, 2016).

In Local 731 Pension Trust Fund v. Diodes, Inc., the Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of securities claims related to the alleged nondisclosure of labor problems at a Shanghai manufacturing plant, finding a failure to adequately allege scienter. Most basically, the Court observed — “It is important to note the curious nature of the Fund’s claims. To recap the relevant facts: during the class period, Diodes repeatedly warned investors of a labor shortage that would affect its output in the first two quarters of 2011; Diodes accurately warned the precise impact this labor shortage would have on its financial results, not once, but twice. Yet the Fund contends that more disclosure was required.” The Court went on to reject arguments about the unique knowledge of the relevant executives, the company’s decision to make an early product shipment (noting this would have made the labor problem worse and more apparent), and circumstances of an insider’s stock sales. No. 14-41141 (Jan. 13, 2016).

In Local 731 Pension Trust Fund v. Diodes, Inc., the Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of securities claims related to the alleged nondisclosure of labor problems at a Shanghai manufacturing plant, finding a failure to adequately allege scienter. Most basically, the Court observed — “It is important to note the curious nature of the Fund’s claims. To recap the relevant facts: during the class period, Diodes repeatedly warned investors of a labor shortage that would affect its output in the first two quarters of 2011; Diodes accurately warned the precise impact this labor shortage would have on its financial results, not once, but twice. Yet the Fund contends that more disclosure was required.” The Court went on to reject arguments about the unique knowledge of the relevant executives, the company’s decision to make an early product shipment (noting this would have made the labor problem worse and more apparent), and circumstances of an insider’s stock sales. No. 14-41141 (Jan. 13, 2016).

In the wake of the Deepwater Horizon accident, plaintiffs sought to bring two class actions against BP alleging violations of federal securities law — one regarding BP’s representations about its pre-spill safety procedures, and one about BP’s post-accident statements as to the flow rate of oil after the spill occurred. The district court certified the post-spill class, concluding that the plaintiffs had established a model of damages consistent with their liability case and capable of measurement across the class, and refused to certify the pre-spill class, finding that it had not satisfied the “common damages” burden established by the Supreme Court in Comcast Corp. v. Behrend, 133 S. Ct. 1426 (2013). The Fifth Circuit affirmed. As to the post-spill class, the Court reviewed BP’s criticisms of the plaintiffs’ damages expert, and found that they were not so potent as to invalidate his theory at the class certification stage. As to the pre-spill class, however, the Court agreed that the expert failed to exclude class members who would have bought the stock even with full knowledge of the alleged risks, making his analysis infirm for certification purposes. Ludlow v. BP, PLC, No. 14-20420 (revised Sept.15, 2015).

In the wake of the Deepwater Horizon accident, plaintiffs sought to bring two class actions against BP alleging violations of federal securities law — one regarding BP’s representations about its pre-spill safety procedures, and one about BP’s post-accident statements as to the flow rate of oil after the spill occurred. The district court certified the post-spill class, concluding that the plaintiffs had established a model of damages consistent with their liability case and capable of measurement across the class, and refused to certify the pre-spill class, finding that it had not satisfied the “common damages” burden established by the Supreme Court in Comcast Corp. v. Behrend, 133 S. Ct. 1426 (2013). The Fifth Circuit affirmed. As to the post-spill class, the Court reviewed BP’s criticisms of the plaintiffs’ damages expert, and found that they were not so potent as to invalidate his theory at the class certification stage. As to the pre-spill class, however, the Court agreed that the expert failed to exclude class members who would have bought the stock even with full knowledge of the alleged risks, making his analysis infirm for certification purposes. Ludlow v. BP, PLC, No. 14-20420 (revised Sept.15, 2015).

The Texas Securities Act has a five-year statute of repose. The issue in FDIC v. RBS Securities was whether that statute was preempted by a 3-year “extender” provision in FIRREA, which “works by hooking any claims that are alive at the time of the FDIC’s appointment as receiver and pulling them forward to a new, federal, minimum limitations period — six years for contract claims, three years for tort claims.” No. 14-51055 (Aug. 10, 2015).

The Texas Securities Act has a five-year statute of repose. The issue in FDIC v. RBS Securities was whether that statute was preempted by a 3-year “extender” provision in FIRREA, which “works by hooking any claims that are alive at the time of the FDIC’s appointment as receiver and pulling them forward to a new, federal, minimum limitations period — six years for contract claims, three years for tort claims.” No. 14-51055 (Aug. 10, 2015).

The Fifth Circuit concluded that the Texas statute of repose was preempted, and reversed a judgment on the pleadings in a securities fraud suit arising out of the failure of Guaranty Bank, holding: “The text, structure, and purpose of the FDIC Extender Statute all evince a Congressional intent to grant the FDIC a three-year grace period after its appointment as receiver to investigate potential claims. Therefore, the statute displaces any limitations period that would interfere with that reprieve — whether characterized as a statute of limitations or as a statute of repose.” The Court distinguished the analysis of a CERCLA limitations provision in CTS Corp. v. Waldburger, 134 S. Ct. 2175 (2014), finding that “many of the considerations that the [Supreme] Court found disfavored preemption in CTS suggest preemption when applied to the FDIC Extender Statute.”

The plaintiffs in Owens v. Jastrow sued officers of Guaranty Bank for securities fraud, alleging that their SEC filings and public comments misstated the vulnerability of the bank’s mortgage-related holdings. No. 13-10928 (June 12, 2015). The Fifth Circuit affirmed dismissal in a detailed opinion, holding, procedurally, that:

The plaintiffs in Owens v. Jastrow sued officers of Guaranty Bank for securities fraud, alleging that their SEC filings and public comments misstated the vulnerability of the bank’s mortgage-related holdings. No. 13-10928 (June 12, 2015). The Fifth Circuit affirmed dismissal in a detailed opinion, holding, procedurally, that:

- “A district court may best make sense of scienter allegations by first looking to the contribution of each individual allegation to a strong inference of scienter, especially in a complicated case such as this one. Of course, the court must follow this initial step with a holistic look at all the scienter allegations”; and

- “Group pleaded” allegations were properly disregarded, although the Court declined to adopt “a strict rule requiring outright dismissal for any group or puzzle pleading[.]”

And on the merits:

- Knowledge of undercapitalization showed motive and opportunity, but does not by itself establish scienter;

- “Defendants’ disclosure of the ‘red flags’ [cited by Plainitiffs] and candidness about the uncertainly underlying its models neutralize any scienter inference from ‘red flags'”; and

- “An inference of severe recklessness is more likely when a statement violates an objective rule than when GAAP permits a range of acceptable outcomes.”

Therefore: “Considered holistically, plaintiffs’ allegations of knowledge of Guaranty’s undercapitalization, a large misstatement, red flags, and ignorance of internal warnings, do not raise a strong inference of severe recklessness that is equally as likely as the competing inference that [Defendants] negligently relief on the AAA ratings and believed that Guaranty’s internal models were accurate.”

Plaintiffs sued for securities fraud about their investments in a business that auctioned antiques. Heck v. Triche, No. 14-30146 (Dec. 23, 2014). They won on many claims at trial and the Fifth Circuit affirmed, largely on procedural grounds:

Plaintiffs sued for securities fraud about their investments in a business that auctioned antiques. Heck v. Triche, No. 14-30146 (Dec. 23, 2014). They won on many claims at trial and the Fifth Circuit affirmed, largely on procedural grounds:

1. Appeal Deadline Extended. As a threshold matter, the plaintiffs’ motion for attorneys fees tolled the deadline for the notice of appeal, because the district court entered an order under Fed. R. Civ. P. 83(e) that stayed the deadline until the disposition of the motion. The Court noted some tension between its analysis of this issue and that of the Second Circuit’s in Mendes Junior Int’l Co. v. Banco Do Brasil, S.A., 215 F.3d 306 (2000).

2. Invited Charge Error. The Court agreed that the district court’s verdict form erroneously conflated the elements of a federal 10b-5 claim with those of a Louisiana securities claim. It found, however, that the plaintiffs invited this error by advocating for this part of the charge (citing United States v. Gray, 626 F.2d 494, 501 n.2 (5th Cir. 1980) [“The invited error doctrine bars reversal even if the instruction constituted plain error.”])

3. Cross-Appeal Needed. The plaintiffs argued that the district court erred by imposing liability under state law, not 10b-5. The Court found this argument waived, because its acceptance would change the amount of the judgment as well as its basis, and the plaintiffs did not cross-appeal.

Plaintiffs alleged that Amedisys, a provider of home health services, concealed billing improprieties, causing a drop in its stock value when they were revealed. Public Employees’ Retirement System of Mississippi v. Amedisys, Inc., No. 13-30580 (Oct. 2, 2014). The Fifth Circuit reversed the district court’s dismissal on the pleadings, finding adequate allegations of loss causation. It based its holding on the alleged cumulative effect of the five pleaded disclosures of the allegedly concealed information: “This holding can best be understood by simply observing that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” In its discussion of the Supreme Court’s treatment of this pleading issue in Dura Phamaceuticals, Inc. v. Broudo, 544 U.S. 336 (2005), the Court pointed out that Dura relied on Conley v. Gibson for its summary of pleading requirements — perhaps inviting a reassessment of that holding in light of later developments under Twombly and Iqbal.

Plaintiffs sued for securities fraud, alleging misrepresentations about a company’s capabilities and plans about drilling for oil. Spitzberg v. Houston American Energy Corp.. No. 13-20519 (July 15, 2014). Emphasizing the plaintiffs’ arguments about “the industry definitions of . . . terms” and the timing of events giving rise to an inference of scienter, the Fifth Circuit reversed the dismissal of their claims under the PSLRA,. The Court also found adequate pleading of loss causation. (The significance of industry terminology echoes the reversal of a Rule 12 dismissal about the sale of a loan in Highland Capital Management LP v. Bank of America, although that claim ultimately lost at the summary judgment stage.)

After the Deepwater Horizon disaster, BP’s share price declined and several employee benefits sustained major losses. An ERISA lawsuit on behalf of the beneficiaries was dismissed, noting that an ERISA fiduciary’s to maintain an investment in company stock receives a “presumption of prudence,” sometimes referred to as the Moench presumption. Whitley v. BP, P.L.C., No. 12-20670 (July 15, 2014, unpublished). In June 2014, the Supreme Court eliminated that presumption and held that ERISA fiduciaries managing a plan invested in company stock are subject to the same duty of prudence as any other ERISA fiduciary, “except that they need not diversify the fund’s assets.” Fifth Third Bancorp v. Dudenhoeffer, No. 12-751 (U.S. June 25, 2014). Accordingly, the Fifth Circuit vacated the district court’s dismissal and remanded the appeal for reconsideration in light of that opinion.

The SEC settled an enforcement action except as to the issue of potential disgorgement. SEC v. Halek, No. 12-11045 (August 5, 2013). Negotiations then broke down because the SEC did not accept the financial information provided by the defendants. The district court then entered an order to disgorge over $20 million. In affirming the district court, the Fifth Circuit: (1) found no abuse of discretion in reopening the case, noting that “[a]n administrative closure is more akin to a stay than a dismissal,” (2) reminded that “[d]istrict courts have ‘broad discretion in fashioning the equitable remedy of a disgorgement order,'” and (3) found no clear error in the court’s determinations about joint and several liablity, the reasonableness of the ordered amount as an approximation of the defendants’ unlawful gain, or its decision not to credit settlement payments against the ordered amount.

The plaintiff in Asadi v. G.E. Energy (USA), LLC was terminated after making an internal report of a potential securities law violation. No. 12-20522 (July 17, 2013). The Fifth Circuit affirmed the Rule 12 dismissal of his whistleblower claim based on Dodd-Frank: “Based on our examination of the plain language and structure of the whistleblower-protection provision, we conclude that the whistleblower protection provision unambiguously requires individuals to provide information relating to a violation of the securities laws to the SEC to qualify for protection . . . . (emphasis in original)” The Court acknowledged a more expansive SEC regulation on the point, but found it was not entitled to Chevron deference given the clarity of the statute.

A putative plaintiff class alleged violations of federal securities law by alleged misstatements about asbestos liabilities, the quality of certain receivables and the claimed benefits of a merger. Erica P. John Fund Inc. v. Halliburton, Inc., No. 12-10544 (April 30, 2013). Reviewing recent Supreme Court cases about relevant evidence at the certification stage, including one that reversed the Fifth Circuit about proof of loss causation, the Court held: “price impact fraud-on-the-market rebuttal evidence should not be considered at class certification. Proof of price impact is based upon common evidence, and later proof of no price impact will not result in the possibility of individual claims continuing.” (citing Amgen, Inc. v. Connecticut Retirement Plans and Trust Funds, ___ U.S. ___ (Feb. 27, 2013)) The Court rejected a policy argument about the potential “in terrorem” effect of not considering such potentially dispositive evidence about the merits at the certification stage. The district court ruling about this evidence, and the resulting class certification, were affirmed.

An unpublished opinion reversed the vacating of a FINRA arbitration award in Morgan Keegan v. Garrett, No. 11-20736 (Oct. 23, 2012). The Court reversed a finding of fraudulent testimony “because the grounds for [the alleged] fraud were discoverable by due diligence before or during the . . . arbitration.” Id. at 8. The Court also deferred to the panel’s conclusions about the scope of the arbitration as consistent with the authority given by the FINRA rules. Id. at 10-12. Throughout, the opinion summarizes Circuit authority about the appropriate level of deference to the panel in a confirmation seting.

An unpublished opinion affirmed a ruling that an SEC suit about backdating was barred by limitations and the discovery rule did not apply. SEC v. Microtune, No. 11-10594 (Aug. 7, 2012). An interesting analysis of the opinion and its potential broader significance appears in the August 11, 2012 Texas LawBook.

In a detailed opinion that surveyed differing Circuit opinions on several topics, the Court found that “the purchase or sale of securities (or representations about the purchase or sale of securities) is only tangentially related to the fraudulent scheme alleged” in state class actions about the Allen Stanford scandal. Roland v. Green (March 19, 2012). Therefore, the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act (SLUSA) did not preclude those actions. The opinion will likely have a significant influence on future cases about the scope of SLUSA in the Fifth Circuit.