The high-stakes mandamus petition in In re DuPuy Orthopaedics, Inc., No. 17-10812 (Aug. 31, 2017), sought relief from an upcoming set of “bellweather” trials in a massive MDL proceeding about allegedly defective hip implants. After an hour-long oral argument – and despite Hurricane Harvey’s enormous impact on Houston, where all three panelists are based – the panel denied the petition a week after argument in an unusual “split decision.”

The high-stakes mandamus petition in In re DuPuy Orthopaedics, Inc., No. 17-10812 (Aug. 31, 2017), sought relief from an upcoming set of “bellweather” trials in a massive MDL proceeding about allegedly defective hip implants. After an hour-long oral argument – and despite Hurricane Harvey’s enormous impact on Houston, where all three panelists are based – the panel denied the petition a week after argument in an unusual “split decision.”

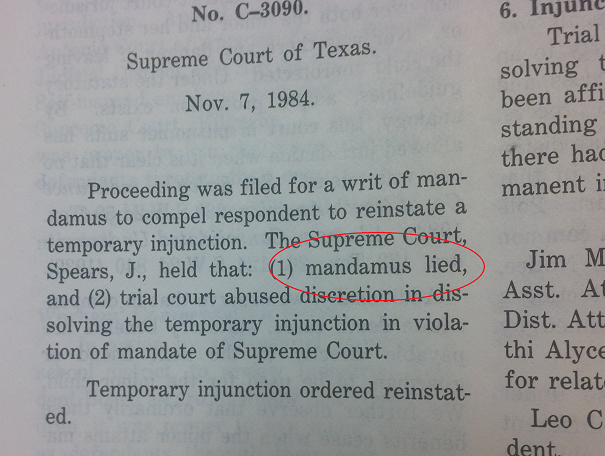

As to the underlying substantive issue – whether the trials could proceed despite strong arguments about personal jurisdiction – two of the three panelists (Judges Smith and Jones) found that a clear error had been committed. But as to mandamus relief, two of the three panelists (Judges Smith and Costa) concluded that the defendants had an adequate remedy by direct appeal.

The opinion has four implications for mandamus practice in the Fifth Circuit, generally.

First, Judge Costa now has a “track record” about mandamus petitions, and his observations in this case – consistent with his prior experience as a trial judge – suggest he has a restrictive view about its availability.

Second, if there was any doubt that mandamus is essentially limited to forum-selection disputes in the Fifth Circuit, the analysis of “adequate remedy” by the panel majority on that point should eliminate it. The unusual length and expense of the upcoming trial, coupled with its potential impact on settlement discussions for the entire MDL, was seen as the type of litigation expense and “hardship [that] may result from delay” that will not justify a mandamus petition.

Third, by detailing a panel majority’s view that the trial court had erred, the opinion continues a practice of offering something of an “advisory opinion” about the merits, despite declining to issue the writ. Indeed, footnote 4 of the opinion gives several examples of other opinions that have done so; two other recent examples include the opinions in In re: Crystal Power Co., 641 F.3d 82 (5th Cir. 2011) (“We confess puzzlement over why respondents insist on litigating this case in federal court even though . . . any judgment issued by the district court will su ely be reversed . . . . “) and In re: Trinity Industries, No. 14-41067 (Oct. 10, 2014) (“The court is compelled to note, however, that this is a close case.”)

Fourth, the opinion highlights the difference between federal and Texas state mandamus practice, despite the nominally similar tests used by the two court systems. A leading Texas Supreme Court case about the adequacy of appellate remedy observes: “Although this Court has tried to give more concrete direction for determining the availability of mandamus review, rigid rules are necessarily inconsistent with the flexibility that is the remedy’s principal virtue.” In re: Prudential Ins. Co., 148 S.W.3d 124 (Tex. 2004). The DuPuy panel majority has a different view of the point.

With most high-profile public-law litigation in the Second and Ninth Circuits at present, the recent “Venue Wars” have cooled off, but venue disputes persist. In In re Trubridge, Inc., the Fifth Circuit found no clear abuse of discretion in denying a transfer motion, even though a forum-selection clause referred to Alabama courts.

With most high-profile public-law litigation in the Second and Ninth Circuits at present, the recent “Venue Wars” have cooled off, but venue disputes persist. In In re Trubridge, Inc., the Fifth Circuit found no clear abuse of discretion in denying a transfer motion, even though a forum-selection clause referred to Alabama courts.