An unusual but intriguing coverage dispute arose after the insured’s death as a result of a bite from a mosquito infected with the dangerous West Nile virus. The Fifth Circuit reversed summary judgment for the carrier, observing in its analysis of the policy’s coverage for “accidental injury” –

An unusual but intriguing coverage dispute arose after the insured’s death as a result of a bite from a mosquito infected with the dangerous West Nile virus. The Fifth Circuit reversed summary judgment for the carrier, observing in its analysis of the policy’s coverage for “accidental injury” –

- The importance of defining the specific injury – “Instead of focusing on Melton’s bite from a WNV-infected Culex mosquito, Minnesota Life argues that a mosquito bite generally is not unexpected and unforeseen in Texas. But a bite by a generic mosquito is not the accidental injury Gloria pleaded in her complaint; instead, she says it is the bite by a WNV-infected Culex mosquito that triggers coverage. Without guidance from the policy as to how broadly or narrowly an ;’accidental bodily injury’ is to be defined, we take the facts of the alleged accidental injury as

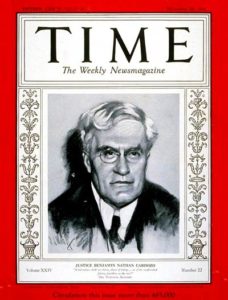

Gloria contends.” - And as to whether an injury as “accidental” – the Court quoted then-Judge Cardozo’s analysis from a 1925 opinion about inhalation of an airborne pathogen: “Germs may indeed be inhaled through the nose or mouth, or absorbed into the system through normal channels of entry. In such cases their inroads will seldom, if ever, be assignable to a determinate or single act, identified in space or time. For this as well as for the reason that the absorption is incidental to a bodily process both natural and normal, their action presents itself to the mind as a disease and not an accident.”

- But the Court distinguished the situation addressed by Judge Cardozo: “Here, however, there was a determinate, single act—the bite—that is not incidental to a bodily process. The mosquito, an external “physical” force, affirmatively acted to cause Melton harm and produce an unforeseen result. We find that inhaling a community-spread pathogen and being bitten by a mosquito can be thinly sliced so as to be distinguishable.”

Wells v. Minnesota Life, No. 16-20831 (March 22, 2018).

sed in Texas case law that we have seen.” The endorsement dealt with personal property. The district court granted summary judgment for the insured, concluding that the “actual cash value” described in the endorsement could not be proved with the insured’s affidavit about replacement cost. The Fifth Circuit disagreed and reversed, noting that the Texas Supreme Court has acknowledged that “personal effects have ‘no market value in the ordinary meaning of that term,'” meaning that “[t]he trier of facts may consider original cost and cost of replacement,” among other evidence. No. 14-51301 (Jan. 28, 2016, unpublished).

sed in Texas case law that we have seen.” The endorsement dealt with personal property. The district court granted summary judgment for the insured, concluding that the “actual cash value” described in the endorsement could not be proved with the insured’s affidavit about replacement cost. The Fifth Circuit disagreed and reversed, noting that the Texas Supreme Court has acknowledged that “personal effects have ‘no market value in the ordinary meaning of that term,'” meaning that “[t]he trier of facts may consider original cost and cost of replacement,” among other evidence. No. 14-51301 (Jan. 28, 2016, unpublished).