In a return trip to the Fifth Circuit, the defamation case of Block v. Tanenhaus again sidestepped the question of whether state anti-SLAPP laws apply in federal courrt, allowing that elephant to remain in the Erie room for awhile longer. Here, assuming that the Lousiana state law applied, the panel reversed and remanded the dismissal of a professor’s claim that the New York Times misquoted him. Jess Krochtengel summarizes the underlying Erie question and its implications in a recent Law360 article. No. 16-30966 (Aug. 15, 2017).

In a return trip to the Fifth Circuit, the defamation case of Block v. Tanenhaus again sidestepped the question of whether state anti-SLAPP laws apply in federal courrt, allowing that elephant to remain in the Erie room for awhile longer. Here, assuming that the Lousiana state law applied, the panel reversed and remanded the dismissal of a professor’s claim that the New York Times misquoted him. Jess Krochtengel summarizes the underlying Erie question and its implications in a recent Law360 article. No. 16-30966 (Aug. 15, 2017).

Category Archives: Erie

Guilbeau bought real property and sued Hess Corporation for alleged contamination resulting from oil and gas drilling done several years before. Acknowledging that the Louisiana Supreme Court had not ruled on the precise issue presented – whether the “subsequent purchaser” rule applied to mineral interests – the Fifth Circuit concluded that Louisiana law would bar Guilbeau’s claim. A consensus of Louisiana intermediate courts, applying the most analogous authority from that state’s Supreme Court, reasoned “that while mineral rights in the lessee are real rights, a lessor’s rights, including the right to sue for damages, are personal and do not automatically transfer with the property” absent an assignment. Guilbeau v. Hess Corp., No. 16-30971 (April 18, 2017).

Guilbeau bought real property and sued Hess Corporation for alleged contamination resulting from oil and gas drilling done several years before. Acknowledging that the Louisiana Supreme Court had not ruled on the precise issue presented – whether the “subsequent purchaser” rule applied to mineral interests – the Fifth Circuit concluded that Louisiana law would bar Guilbeau’s claim. A consensus of Louisiana intermediate courts, applying the most analogous authority from that state’s Supreme Court, reasoned “that while mineral rights in the lessee are real rights, a lessor’s rights, including the right to sue for damages, are personal and do not automatically transfer with the property” absent an assignment. Guilbeau v. Hess Corp., No. 16-30971 (April 18, 2017).

In Ocwen Loan Servicing LLC v. Berry, a dispute about a home equity loan, the Fifth Circuit confirmed that “we now must follow the Texas Supreme Court’s holding in [Wood v. HSBC Bank USA, N.A., 505 S.W.3d 542 (Tex. 2016)] that no statute of limitations applies to a borrower’s allegations of violations of section 50(a)(6) of the Texas Constitution in a quiet title action, rather than our prior holding in [Priester v. JP Morgan Chase Bank, N.A., 708 F.3d 667 (5th Cir. 2013)].” In so doing, the Court reminded that “the issues-not-briefed-are-waived rule is a prudential construct that requires the exercise of discretion,” and addressed the applicability of Wood notwithstanding the appellant not discussing the case in its opening brief, noting that the underlying issues had been briefed, and that the Court had received supplemental briefing on the pure question of law presented about the application of Wood. No. 16-10604 (March 29, 2017).

In Ocwen Loan Servicing LLC v. Berry, a dispute about a home equity loan, the Fifth Circuit confirmed that “we now must follow the Texas Supreme Court’s holding in [Wood v. HSBC Bank USA, N.A., 505 S.W.3d 542 (Tex. 2016)] that no statute of limitations applies to a borrower’s allegations of violations of section 50(a)(6) of the Texas Constitution in a quiet title action, rather than our prior holding in [Priester v. JP Morgan Chase Bank, N.A., 708 F.3d 667 (5th Cir. 2013)].” In so doing, the Court reminded that “the issues-not-briefed-are-waived rule is a prudential construct that requires the exercise of discretion,” and addressed the applicability of Wood notwithstanding the appellant not discussing the case in its opening brief, noting that the underlying issues had been briefed, and that the Court had received supplemental briefing on the pure question of law presented about the application of Wood. No. 16-10604 (March 29, 2017).

Gatheright bought sweet potatoes from Clark, paying with two post-dated checks. When they were returned for insufficient funds, Clark instituted criminal proceedings against Gatheright, which were ultimately dismissed after Gatheright spent several weeks in jail. Gatheright then sued Clark for malicious prosecution and abuse of process. The Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for Clark, observing that “$16,000 in bad checks . . . [is] a sum greater than what the Mississippi Supreme Court has previously found would prompt a reasonable person to institute criminal proceedings.” Based on that observation, the Court rejected arguments about whether a post-dated

Gatheright bought sweet potatoes from Clark, paying with two post-dated checks. When they were returned for insufficient funds, Clark instituted criminal proceedings against Gatheright, which were ultimately dismissed after Gatheright spent several weeks in jail. Gatheright then sued Clark for malicious prosecution and abuse of process. The Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for Clark, observing that “$16,000 in bad checks . . . [is] a sum greater than what the Mississippi Supreme Court has previously found would prompt a reasonable person to institute criminal proceedings.” Based on that observation, the Court rejected arguments about whether a post-dated  check was a proper basis for a “false pretenses” prosecution in Mississippi, and about the effect of Gatheright’s filing for personal bankruptcy. Gatheright v. Clark, No. 16-60364 (Feb. 23, 2017, unpublished).

check was a proper basis for a “false pretenses” prosecution in Mississippi, and about the effect of Gatheright’s filing for personal bankruptcy. Gatheright v. Clark, No. 16-60364 (Feb. 23, 2017, unpublished).

Last year, the Fifth Circuit certified these two questions to the Texas Supreme Court:

Last year, the Fifth Circuit certified these two questions to the Texas Supreme Court:

1. Does a lender or holder violate Article XVI, Section 50(a)(6)(Q)(vii) of the Texas Constitution, becoming liable for forfeiture of principal and interest, when the loan agreement incorporates the protections of Section 50(a)(6)(Q)(vii), but the lender or holder fails to return the cancelled note and release of lien upon full payment of the note and within 60 days after the borrower informs the lender or holder of the failure to comply?

2. If the answer to Question 1 is “no,” then, in the absence of actual damages, does a lender or holder become liable for forfeiture of principal and interest under a breach of contract theory when the loan agreement incorporates the protections of Section 50(a)(6)(Q)(vii), but the lender or holder, although filing a release of lien in the deed records, fails to return the cancelled note and release of lien upon full payment of the note and within 60 days after the borrower informs the lender or holder of the failure to comply?

The T exas Supreme Court answered both questions “no” in Garofolo v. Ocwen Loan Servicing, No. 15-0437 (Tex. May 20, 2016). Accordingly, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of the plaintiff’s contract claim in Garofolo v. Ocwen Loan Servicing, No. 14-51156 (Oct. 3, 2016, unpublished).

exas Supreme Court answered both questions “no” in Garofolo v. Ocwen Loan Servicing, No. 15-0437 (Tex. May 20, 2016). Accordingly, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of the plaintiff’s contract claim in Garofolo v. Ocwen Loan Servicing, No. 14-51156 (Oct. 3, 2016, unpublished).

Hays, a cardiologist suffering from epilepsy, sued HCA for wrongful discharge as a result of mishandling his illness. The Fifth Circuit agreed that his tortious interference claim against HCA had to be arbitrated, because its viability depended on reference to the employment agreement between him and the specific hospital where he worked. It also affirmed on the theory of “intertwined claims estoppel,” making an Erie guess that the Texas Supreme Court would recognize this theory, and concluding that “Hays’s current efforts to distinguish amongst defendants and claims are the archetype of strategic pleading intended to avoid the arbitral forum, precisely what intertwined claims estoppel is designed to prevent.” Hays v. HCA Holdings, No. 15-51002 (Sept. 29, 2016).

Hays, a cardiologist suffering from epilepsy, sued HCA for wrongful discharge as a result of mishandling his illness. The Fifth Circuit agreed that his tortious interference claim against HCA had to be arbitrated, because its viability depended on reference to the employment agreement between him and the specific hospital where he worked. It also affirmed on the theory of “intertwined claims estoppel,” making an Erie guess that the Texas Supreme Court would recognize this theory, and concluding that “Hays’s current efforts to distinguish amongst defendants and claims are the archetype of strategic pleading intended to avoid the arbitral forum, precisely what intertwined claims estoppel is designed to prevent.” Hays v. HCA Holdings, No. 15-51002 (Sept. 29, 2016).

The Fifth Circuit recently denied en banc review — by a “photo finish” 8-7 vote — of Passmore v. Baylor Health System, which concluded that Texas’s expert report requirements for medical malpractice cases were procedural and did not apply in federal court under the Erie doctrine. A dissent argued that this vote was inconsistent with the recent en banc opinion in Flagg v. Stryker Corp. that analyzed a comparable requirement of Louisiana law.

The Fifth Circuit recently denied en banc review — by a “photo finish” 8-7 vote — of Passmore v. Baylor Health System, which concluded that Texas’s expert report requirements for medical malpractice cases were procedural and did not apply in federal court under the Erie doctrine. A dissent argued that this vote was inconsistent with the recent en banc opinion in Flagg v. Stryker Corp. that analyzed a comparable requirement of Louisiana law.

For some time, the Golf Channel and the receiver for Allen Stanford’s affairs have disputed whether the Channel gave value in exchange for the purchase of roughly $6 million in advertising. The Channel contended that it did by giving exactly the advertising that Stanford ordered; the receiver disagreed, noting that Stanford was running a valueless Ponzi scheme. On certification from the Fifth Circuit, the Texas Supreme Court sided with the Channel, holding that under the Texas version of the Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Act, the Channel gave value from an objective perspective. The Fifth Circuit accepted that holding as to this case, but noted: “The Supreme Court of Texas’s answer interprets the concept of ‘value’ under TUFTA differently than we have understood ‘value’ under other states’ fraudulent transfer laws and under section 548(c) [of] the Bankruptcy Code.” Janvey v. Golf Channel, No. 13-11305 (Aug. 22, 2016).

For some time, the Golf Channel and the receiver for Allen Stanford’s affairs have disputed whether the Channel gave value in exchange for the purchase of roughly $6 million in advertising. The Channel contended that it did by giving exactly the advertising that Stanford ordered; the receiver disagreed, noting that Stanford was running a valueless Ponzi scheme. On certification from the Fifth Circuit, the Texas Supreme Court sided with the Channel, holding that under the Texas version of the Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Act, the Channel gave value from an objective perspective. The Fifth Circuit accepted that holding as to this case, but noted: “The Supreme Court of Texas’s answer interprets the concept of ‘value’ under TUFTA differently than we have understood ‘value’ under other states’ fraudulent transfer laws and under section 548(c) [of] the Bankruptcy Code.” Janvey v. Golf Channel, No. 13-11305 (Aug. 22, 2016).

Presenting a textbook Erie problem, Passmore sued Baylor Regional Medical Center about his back surgeries in federal court based on bankruptcy jurisdiction. The defendants obtained dismissal on the expert report requirements in section 74.351 of the Texas Civil Practice & Remedies Code. Reviewing the requirements of that statute, the requirements of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure governing discovery, and district court opinions on the matter, the Fifth Circuit reversed, holding: “Section 74.351’s regulation of discovery and discovery-related sanctions sets it apart from the pre-suit requirements in the cases cited by the defendants and brings it into direct collision with Rules 26 and 37.” Passmore v. Baylor Health Care System, No. 15-10358 (May 19, 2016).

Presenting a textbook Erie problem, Passmore sued Baylor Regional Medical Center about his back surgeries in federal court based on bankruptcy jurisdiction. The defendants obtained dismissal on the expert report requirements in section 74.351 of the Texas Civil Practice & Remedies Code. Reviewing the requirements of that statute, the requirements of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure governing discovery, and district court opinions on the matter, the Fifth Circuit reversed, holding: “Section 74.351’s regulation of discovery and discovery-related sanctions sets it apart from the pre-suit requirements in the cases cited by the defendants and brings it into direct collision with Rules 26 and 37.” Passmore v. Baylor Health Care System, No. 15-10358 (May 19, 2016).

After a bad start in the Fifth Circuit, the Golf Channel ultimately prevailed in the Texas Supreme Court in a fraudulent transfer case against the Allen Stanford receiver. The Channel ran advertisements for Stanford’s golf business in exchange for payments of roughly $6 million. The issue was whether the “value” of those ads, for purposes of the Channel’s defenses under TUFTA, “became valueless based on the true nature of the debtor’s business as a Ponzi scheme or the debtor’s subjective reasons for procuring otherwise lawful services.” The Texas Supreme Court ruled for the Channel, finding that “TUFTA does not contain separate standards for assessing ‘value’ and ‘reasonably equivalent’ value based on whether the debtor was operating a Ponzi scheme. . . . “[V]alue must be determined objectively at the time of the transfer and in relation to the individual exchange at hand rather than viewed in the context of the debtor’s entire enterprise, . . . the debtor’s perspective, or . . . a retrospective evaluation of the impact it had on the debtor’s estate.” Janvey v. Golf Channel, No. 15-0489 (Tex. Apr. 1, 2016).

After a bad start in the Fifth Circuit, the Golf Channel ultimately prevailed in the Texas Supreme Court in a fraudulent transfer case against the Allen Stanford receiver. The Channel ran advertisements for Stanford’s golf business in exchange for payments of roughly $6 million. The issue was whether the “value” of those ads, for purposes of the Channel’s defenses under TUFTA, “became valueless based on the true nature of the debtor’s business as a Ponzi scheme or the debtor’s subjective reasons for procuring otherwise lawful services.” The Texas Supreme Court ruled for the Channel, finding that “TUFTA does not contain separate standards for assessing ‘value’ and ‘reasonably equivalent’ value based on whether the debtor was operating a Ponzi scheme. . . . “[V]alue must be determined objectively at the time of the transfer and in relation to the individual exchange at hand rather than viewed in the context of the debtor’s entire enterprise, . . . the debtor’s perspective, or . . . a retrospective evaluation of the impact it had on the debtor’s estate.” Janvey v. Golf Channel, No. 15-0489 (Tex. Apr. 1, 2016).

In another case that defly manuevers around the thorny Erie issues presented by state anti-SLAPP laws, the Fifth Circuit reminded that Louisiana’s law imposes a burden that “is the same as that of a non-movant opposing summary judgment under Rule 56.” (applying Lozovyy v. Kurtz, No. 15-30086 (5th Cir. Dec. 29, 2015)). The Court assumed the law would apply, but noted: “We do not conclusively resolve today whether Article 971 applies in diversity cases.” Block v. Tanenhaus, No. 15-30459 (March 7, 2016).

In another case that defly manuevers around the thorny Erie issues presented by state anti-SLAPP laws, the Fifth Circuit reminded that Louisiana’s law imposes a burden that “is the same as that of a non-movant opposing summary judgment under Rule 56.” (applying Lozovyy v. Kurtz, No. 15-30086 (5th Cir. Dec. 29, 2015)). The Court assumed the law would apply, but noted: “We do not conclusively resolve today whether Article 971 applies in diversity cases.” Block v. Tanenhaus, No. 15-30459 (March 7, 2016).

The Texas anti-SLAPP law (the “TCPA”) imposes a number of deadlines that can fit awkwardly with federal practice. The panel majority in Cuba v. Pylant concluded that when no hearing is held on a TCPA motion as required by the statute (hearings being common in Texas state practice but not in federal court), appeal-related deadlines that start from the hearing date do not begin to run. A dissent said: “Applying an Erie analysis, I conclude that the TCPA is procedural and must be ignored.” Nos. 15-10212 & -10213 (Feb. 23, 2016).

The Texas anti-SLAPP law (the “TCPA”) imposes a number of deadlines that can fit awkwardly with federal practice. The panel majority in Cuba v. Pylant concluded that when no hearing is held on a TCPA motion as required by the statute (hearings being common in Texas state practice but not in federal court), appeal-related deadlines that start from the hearing date do not begin to run. A dissent said: “Applying an Erie analysis, I conclude that the TCPA is procedural and must be ignored.” Nos. 15-10212 & -10213 (Feb. 23, 2016).

Cameron International, a main defendant in the Deepwater Horizon cases, successfully sued Liberty Insurance to help cover its substantial settlement costs. After affirming on the merits, the Fifth Circuit certified this question to the Texas Supreme Court: “Whether, to maintain a cause of action under Chapter 541 of the Texas Insurance Code against an insurer that wrongfully withheld policy benefits, an insured must allege and prove an injury independent from the denied policy benefits?” Cameron International Corp. v. Liberty Ins. Underwriters, Inc., No. 14-31321 (Nov. 19, 2015).

Cameron International, a main defendant in the Deepwater Horizon cases, successfully sued Liberty Insurance to help cover its substantial settlement costs. After affirming on the merits, the Fifth Circuit certified this question to the Texas Supreme Court: “Whether, to maintain a cause of action under Chapter 541 of the Texas Insurance Code against an insurer that wrongfully withheld policy benefits, an insured must allege and prove an injury independent from the denied policy benefits?” Cameron International Corp. v. Liberty Ins. Underwriters, Inc., No. 14-31321 (Nov. 19, 2015).

Cardoni v. Prosperity Bank, an appeal from a preliminary injunction ruling in a noncompete case, involved a clash between Texas and Oklahoma law, and led to these noteworthy holdings from the Fifth Circuit in this important area for commercial litigators:

Cardoni v. Prosperity Bank, an appeal from a preliminary injunction ruling in a noncompete case, involved a clash between Texas and Oklahoma law, and led to these noteworthy holdings from the Fifth Circuit in this important area for commercial litigators:

- Under the Texas Supreme Court’s weighing of the relevant choice-of-law factors, Oklahoma has a stronger interest in the enforcement of a noncompete than Texas, “with the employees located in Oklahoma and employer based in Texas”;

- As also noted by that Court, “Oklahoma has a clear policy against enforcement of most noncompetition agreements,” which is not so strong as to nonsolicitation agreements;

- The district court did not clearly err in declining to enforce a nondisclosure agreement, given the unsettled state of Texas law on the “inevitable disclosure” doctrine; and

- “[T]he University of Texas leads the University of Oklahoma 61-44-5 in the Red River Rivalry.”

No. 14-20682 (Oct. 29, 2015).

Employees of the Stanford Financial Group sought coverage for attorneys fees incurred in defending federal criminal charges. The district court held the policy ambiguous and found coverage under the contra proferentem doctrine. The insurer sought reversal based on the “sophisticated insured” exception to that doctrine under Texas law. (A previous panel certified the question whether this exception existed in Texas to the Texas Supreme Court, who declined to answer it by resolving that case on other grounds.) Concluding that if Texas were to recognize the exception, it would

Employees of the Stanford Financial Group sought coverage for attorneys fees incurred in defending federal criminal charges. The district court held the policy ambiguous and found coverage under the contra proferentem doctrine. The insurer sought reversal based on the “sophisticated insured” exception to that doctrine under Texas law. (A previous panel certified the question whether this exception existed in Texas to the Texas Supreme Court, who declined to answer it by resolving that case on other grounds.) Concluding that if Texas were to recognize the exception, it would  apply a “middle-ground approach,” the majority affirmed: “Absent any information about the content of the negotiations, how the contracts were prepared, or other indicators of relative bargaining power, [the insurer] did not present evidence that the insured did or could have influenced the terms of the exclusion.” A dissent would have sidestepped saying anything about the exception, preferring to affirm on the ground that the policy unambiguously provided coverage. Certain Underwriters at Lloyds v. Perraud, No. 14-10849 (Aug. 12, 2015, unpublished).

apply a “middle-ground approach,” the majority affirmed: “Absent any information about the content of the negotiations, how the contracts were prepared, or other indicators of relative bargaining power, [the insurer] did not present evidence that the insured did or could have influenced the terms of the exclusion.” A dissent would have sidestepped saying anything about the exception, preferring to affirm on the ground that the policy unambiguously provided coverage. Certain Underwriters at Lloyds v. Perraud, No. 14-10849 (Aug. 12, 2015, unpublished).

Cox Operating incurred significant expenses in cleaning up pollution and debris at its oil-and-gas facilities after Hurricane Katrina. Its insurer disputed coverage. After a lengthy trial, the district court awarded $9,465,103.22 in damages and $13,064,948.28 in penalty interest under the Texas Prompt Payment Act. The Fifth Circuit affirmed in Cox Operating LLC v. St. Paul Surplus Lines Ins. Co., No. 13-20529 (July 30, 2015).

Cox Operating incurred significant expenses in cleaning up pollution and debris at its oil-and-gas facilities after Hurricane Katrina. Its insurer disputed coverage. After a lengthy trial, the district court awarded $9,465,103.22 in damages and $13,064,948.28 in penalty interest under the Texas Prompt Payment Act. The Fifth Circuit affirmed in Cox Operating LLC v. St. Paul Surplus Lines Ins. Co., No. 13-20529 (July 30, 2015).

After finding that the one-year reporting requirement in Cox’s policy was not an unwaivable limitation on coverage, the Court confronted a “disturbing inconsistency” about the Act. On the one hand, the penalty-interest provision applies generally “[i]f an insurer that is liable for a claim under an insurance policy is not in compliance with this subchapter.” On the other hand, of the Act’s variously deadlines, only one expressly ties its violation to the penalty provision. The Fifth Circuit found for the insured, finding “the construction urged by St. Paul . . . would seem to transform all but one of the Act’s deadlines from commands backed by the threat of penalty interest to suggestions backed by nothing at all.”

An earlier panel opinion found the Golf Channel liable for $5.9 million under the Texas Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Act (“TUFTA”), even though it delivered airtime with that market value, because the purchaser was Allen Stanford while running a Ponzi scheme. Accordingly, the airtime had no value to creditors, despite its market value. On rehearing, the Fifth Circuit vacated its initial opinion and certified the controlling issue to the Texas Supreme

An earlier panel opinion found the Golf Channel liable for $5.9 million under the Texas Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Act (“TUFTA”), even though it delivered airtime with that market value, because the purchaser was Allen Stanford while running a Ponzi scheme. Accordingly, the airtime had no value to creditors, despite its market value. On rehearing, the Fifth Circuit vacated its initial opinion and certified the controlling issue to the Texas Supreme  Court: “Considering the definition of ‘value’ in section 24.004(a) of the Texas Business and Commerce Code, the definition of ‘reasonably equivalent value’ in section 24.004(d) of the Texas Business and Commerce Code, and the comment in the Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Act stating that ‘value’ is measured ‘from a creditor’s viewpoint,’ what showing of ‘value’ under TUFTA is sufficient for a transferee to prove the elements of the affirmative defense under section 24.009(a) of the Texas Business and Commerce Code?” Janvey v. The Golf Channel, No. 13-11305 (June 30, 2015).

Court: “Considering the definition of ‘value’ in section 24.004(a) of the Texas Business and Commerce Code, the definition of ‘reasonably equivalent value’ in section 24.004(d) of the Texas Business and Commerce Code, and the comment in the Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Act stating that ‘value’ is measured ‘from a creditor’s viewpoint,’ what showing of ‘value’ under TUFTA is sufficient for a transferee to prove the elements of the affirmative defense under section 24.009(a) of the Texas Business and Commerce Code?” Janvey v. The Golf Channel, No. 13-11305 (June 30, 2015).

Three counties sued MERS (“Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems, Inc.”) for violations of various statutes related to the recording of deeds of trust (the Texas equivalent of a mortgage). In a nutshell, MERS is listed as the “beneficiary” on a deed of trust while the note is executed in favor of the lender. “If the lender later transfers the promissory note (or its interest in the note) to another MERS member, no assignment of the deed of trust is created or recorded because . . . MERS remains the nominee for the lender’s successors and assigns.” The counties argued that this arrangement avoided significant filing fees. The Fifth Circuit affirmed judgment for MERS, finding (1) procedurally, that the Texas Legislature did not create a private right of action to enforce the relevant statute and (2) substantively, that the statute was better characterized as a “procedural directive” to clerks rather than an absolute rule. Other claims failed for similar reasons. Harris County v. MERSCORP Inc., No. 14-10392 (June 26, 2015).

Three counties sued MERS (“Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems, Inc.”) for violations of various statutes related to the recording of deeds of trust (the Texas equivalent of a mortgage). In a nutshell, MERS is listed as the “beneficiary” on a deed of trust while the note is executed in favor of the lender. “If the lender later transfers the promissory note (or its interest in the note) to another MERS member, no assignment of the deed of trust is created or recorded because . . . MERS remains the nominee for the lender’s successors and assigns.” The counties argued that this arrangement avoided significant filing fees. The Fifth Circuit affirmed judgment for MERS, finding (1) procedurally, that the Texas Legislature did not create a private right of action to enforce the relevant statute and (2) substantively, that the statute was better characterized as a “procedural directive” to clerks rather than an absolute rule. Other claims failed for similar reasons. Harris County v. MERSCORP Inc., No. 14-10392 (June 26, 2015).

Building on In re Deepwater Horizon, ___ S.W.3d ___, 2015 WL 674744 (Tex. Feb. 13, 2015), in Ironshore Specialty Ins. Co. v. Aspen Underwriting, the Fifth Circuit addressed whether the following insurance policy provision limited the excess insurer’s obligations to a $5 million that the insured was obliged to provide under another contract: “The word ‘Insured,’ wherever used in this Policy, shall mean . . . any person or entity to whom [Insured] is obliged by a written ‘Insurance Contract’ entered into before any relevant ‘Occurrence’ and/or ‘Claim’ to provide insurance such as is afforded by this Policy.” The Court found that it did, even though the contract at issue in Deepwater Horizon had additional provisions that bore on this question. No. 13-51027 (June 10, 2015).

Disputes between borrowers and mortgage servicers are common; jury trials in those disputes are rare. But rare events do occur, and in McCaig v. Wells Fargo Bank, 788 F.3d 463 (5th Cir. 2015), a servicer lost a judgment for roughly $400,000 after a jury trial.

The underlying relationship was defined by a settlement agreement in which “Wells Fargo has agreed to accept payments from the McCaigs and to give the McCaigs the opportunity to avoid foreclosure of the Property; as long as the McCaigs make the required payments consistent with the Forbearance Agreement and the Loan Agreement.” Unfortunately, Wells’s “‘computer software was not equipped to handle’ the settlement and forbearance agreements meaning ‘manual tracking’ was required.” This led to a number of accounting mistakes, which in turn led to unjustified threats to foreclose and other miscommunications.

In reviewing and largely affirming the judgment, the Fifth Circuit reached several conclusions of broad general interest:

- The “bona fide error” defense under the Texas Debt Collection Act allows a servicer to argue that it made a good-faith mistake; Wells did not plead that defense here, meaning that its arguments about a lack of intent were not pertinent to the elements of the Act sued upon by plaintiffs;

- The economic loss rule did not bar the TDCA claims, even though the alleged misconduct breached the parties’ contract: “[I]f a particular duty is defined both in a contract and in a statutory provision, and a party violates the duty enumerated in both sources, the economic loss rule does not apply”;

- A Casteel – type charge issue is not preserved if the objecting party submits the allegedly erroneous question with the comment “If I had to draft this over again, that’s the way I’d draft it”;

- The plaintiffs’ lay testimony was sufficient to support awards for mental anguish; and

- “[A] print-out from [plaintiffs’] attorney’s case management system showing individual tasks performed by the attorney and the date on which those tasks were performed” was sufficient evidence to support the award of attorneys fees.

A dissent took issue with the economic loss holding, and would find all of the plaintiffs’ claims barred; “[t]he majority’s reading of these [TDCA] provisions specifically equates mere contract breach with statutory violations[.]”

Dan Peterson sued his former employer, Bell Helicopter Textron, for age discrimination under the TCHRA. The jury found that age was a motivating factor in his termination, but also found that Bell would have terminated him even without consideration of his age. The district court awarded no damages, but imposed an injunction on Bell about future age discrimination, and awarded Peterson attorneys fees of approximately $340,000. The Fifth Circuit reversed. Noting that the TCHRA allowed an injunction even in light of the unfavorable causation finding, the Court found that plaintiff’s request came too late, as Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(c) “assumes that a plaintiff’s entitlement to relief not specifically pled has been tested adversarially, tried by consent, or at least developed with meaningful notice to the defendant.” Here, Bell showed that it would have tried the case differently had it known an injunction was at issue. Accordingly, the fee award was also vacated. Peterson v. Bell Helicopter Textron, Inc., No. 14-10249 (June 4, 2015). A revised opinion honed the opinion’s analysis as to a potential alternative ground of fee recovery; the same day it issued, the full Court denied en banc review over a lengthy dissent.

Dan Peterson sued his former employer, Bell Helicopter Textron, for age discrimination under the TCHRA. The jury found that age was a motivating factor in his termination, but also found that Bell would have terminated him even without consideration of his age. The district court awarded no damages, but imposed an injunction on Bell about future age discrimination, and awarded Peterson attorneys fees of approximately $340,000. The Fifth Circuit reversed. Noting that the TCHRA allowed an injunction even in light of the unfavorable causation finding, the Court found that plaintiff’s request came too late, as Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(c) “assumes that a plaintiff’s entitlement to relief not specifically pled has been tested adversarially, tried by consent, or at least developed with meaningful notice to the defendant.” Here, Bell showed that it would have tried the case differently had it known an injunction was at issue. Accordingly, the fee award was also vacated. Peterson v. Bell Helicopter Textron, Inc., No. 14-10249 (June 4, 2015). A revised opinion honed the opinion’s analysis as to a potential alternative ground of fee recovery; the same day it issued, the full Court denied en banc review over a lengthy dissent.

Withdrawing an earlier panel opinion, the Fifth Circuit certified two insurance questions to the Louisiana Supreme Court in 2014, which have now been answered:

1. Whether an insurer can be liable for a bad-faith failure-to-settle claim when it never received a firm settlement offer. (The Fifth Circuit noted that a revised statute imposed “an affirmative duty . . . to make a reasonable effort to settle claims,” drawing into question prior case law in the area.) The Louisiana Supreme Court said: “Having determined that the plain language supports the existence of a cause of action in favor of the insured under [the revised statute], we answer this question affirmatively.”

2. Whether an insurer can be liable for “misrepresenting or failing to disclose facts that are not related to the insurance policy’s coverage” — namely, the status of a claim and related settlement negotiations. The answer: ” An insurer can be found liable under [the statute] for misrepresenting or failing to disclose facts that are not related to the insurance policy’s coverage; the statute prohibits the misrepresentation of ‘pertinent facts,’ without restriction to facts ‘relating to any coverages.'”

Accordingly, the Fifth Circuit remanded for further proceedings in Kelly v. State Farm, No. 12-31064 (May 29, 2015, unpublished).

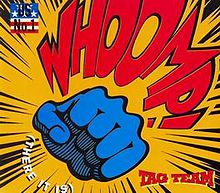

The same week as  the en banc vote in the whooping crane litigation, the Fifth Circuit analyzed “Whoomp! (There It Is).” The unfortunate song has been mired in copyright infringement litigation for a decade; the district court entered judgment for the plaintiff for over $2 million, and it was affirmed in Isbell v. DM Records, Inc., Nos. 13-40787 and 14-40545 (Dec. 18, 2014). [The opinion notes: “The word “‘Whoomp!’ appears to be a neologism, perhaps a variant of ‘Whoop!,’ as in a cry of excitement.”]

the en banc vote in the whooping crane litigation, the Fifth Circuit analyzed “Whoomp! (There It Is).” The unfortunate song has been mired in copyright infringement litigation for a decade; the district court entered judgment for the plaintiff for over $2 million, and it was affirmed in Isbell v. DM Records, Inc., Nos. 13-40787 and 14-40545 (Dec. 18, 2014). [The opinion notes: “The word “‘Whoomp!’ appears to be a neologism, perhaps a variant of ‘Whoop!,’ as in a cry of excitement.”]

The main appellate issue was a variant of a frequently-litigated topic — the role of extrinsic evidence in contract interpretation. The assignment in question was governed by California law, which the Court found to “employ[] a liberal parol evidence rule” with respect to consideration of extrinsic evidence. The appellant argued that the district  court erred “in interpreting the Recording Agreement without asking the jury to make any findings on the extrinsic evidence.” The Court disagreed, finding that the record did not present “a question of the credibility of conflicting extrinsic evidence” (emphasis in original): “The only dispute is over the meaning of the Recording Agreement and the inferences that should be drawn from the numerous undisputed pieces of extrinsic evidence. This is a question of law for the court, not for a jury.”

court erred “in interpreting the Recording Agreement without asking the jury to make any findings on the extrinsic evidence.” The Court disagreed, finding that the record did not present “a question of the credibility of conflicting extrinsic evidence” (emphasis in original): “The only dispute is over the meaning of the Recording Agreement and the inferences that should be drawn from the numerous undisputed pieces of extrinsic evidence. This is a question of law for the court, not for a jury.”

In tour de force reviews of Louisiana’s Civil Code and civilian legal tradition, a plurality and dissent — both written by Louisiana-based judges — reviewed whether a 1923 deed created a “predial servitude” with respect to a right of access. The deed at issue said: “It is understood and agreed that the said Texas & Pacific Railway Company shall fence said strip of ground and shall maintain said fence at its own expense and shall provide three crossings across said strip at the points indicated on said Blue Print hereto attached and made part hereof, and the said Texas and Pacific Railway hereby binds itself, its successors and assigns, to furnish proper drainage out-lets across the land hereinabove conveyed.”

In tour de force reviews of Louisiana’s Civil Code and civilian legal tradition, a plurality and dissent — both written by Louisiana-based judges — reviewed whether a 1923 deed created a “predial servitude” with respect to a right of access. The deed at issue said: “It is understood and agreed that the said Texas & Pacific Railway Company shall fence said strip of ground and shall maintain said fence at its own expense and shall provide three crossings across said strip at the points indicated on said Blue Print hereto attached and made part hereof, and the said Texas and Pacific Railway hereby binds itself, its successors and assigns, to furnish proper drainage out-lets across the land hereinabove conveyed.”

The analysis involved citation to the Revised Civil Code of Louisiana of 1870 (the Code in effect at the time of conveyance), the 1899 treatise Traité de Droit Civil-Des Biens, and the 1893 work, Commentaire théorique & pratique du code civil. Despite the arcane overlay, the opinions turn on practical observations. The plurality notes that the deed uses “successors and assigns” language only with respect to drainage — not access — while the dissent observes that a “personal” access right, limited only to the parties to the conveyance and that does not run with the land, is impractical. Franks Investment Co. v. Union Pacific R.R. Co., No. 13-30990 (Dec. 2, 2014).

Dawna Casey’s family sued Toyota, alleging that the airbag in a 2010 Highlander did not remain inflated for six seconds and caused her death in an accident. The district court granted judgment as a matter of law and the Fifth Circuit affirmed. Casey v. Toyota Motor Engineering & Manufacturing, No. 13-11119 (Oct. 20, 2014).

As to the claim of manufacturing defect, the Court observed: “Casey . . . established only that the air bag did not remain inflated for six seconds,” and relied on alleged violations of Toyota’s performance standards to prove a defect (rather than a technical explanation of the bag’s performance). The Court rejected those allegations under Texas law and precedent from other jurisdictions: “Each piece of evidence submitted by Casey on this point is result-oriented, not manufacturing-oriented, and provides no detail on how the airbag is constructed.”

As to the claim of design defect, Casey relied primarily on a patent application for an allegedly superior design, which the Court rejected as not having been tested under comparable conditions, and as lacking a real-world track record as to feasibility, risk-benefit, and other such matters. Law360 has written a summary of the opinion.

ExxonMobil sued US Metals, alleging over $6 million in damages from defects in a set of 350 “weld neck flanges.” US Metals sought CGL coverage from Liberty. U.S. Metals, Inc. v. Liberty Mutual Group, Inc., No. 1320433 (Sept. 19, 2014, unpublished). Liberty denied US Metals’s request, based on the “your product” and “impaired” property exclusions in the policy, which turned on the terms “physical injury” and “replacement” in those exclusions. The Fifth Circuit noted a lack of Texas authority as to whether those terms are ambiguous in this context, and no clear answer in other opinions that have addressed them. Accordingly, the Court certified two questions to the Texas Supreme Court: (1) whether those terms, as used in these exclusions, are ambiguous; and (2) if so, whether the insured’s interpretation is reasonable. The Court observed that the interpretation of these terms “will have far-reaching implications” and “affect a large number of litigants.” That Court accepted the certification request today.

A vessel sank while in the harbor for repairs. Afterwards, the insurer sued its insured (the harbor operator) and the vessel owner, to dispute coverage. National Liab. & Fire Ins. Co. v. R&R Marine, Inc., No. 10-20767 (June 30, 2014). The insurer argued that the vessel owner had no standing under Texas law when it made a claim against the insurer, as there was no final judgment establishing the insured’s liability at that time. The plaintiff countered that it was “forced” to assert its claim as a compulsory counterclaim under the Federal Rules. The Fifth Circuit concluded that — although Texas state law barred the timing of the vessel owner’s counterclaim, it arose out of the same occurrence as and had a logical relationship to the coverage dispute. Accordingly, the counterclaim was compulsory. Treating it as such also “permitted the district court to efficiently address all disputes arising from the litigation” and was consistent with the Rules’ goal of only “alter[ing] the mode of enforcing state-created rights.”

In Lemoine v. Wolfe, the Fifth Circuit certified an important question of malicious prosecution law to the Louisiana Supreme Court; namely, whether dismissal of a prosecution constitutes a “bona fide termination in his favor” as required by that tort. No. 13-30178 (July 18, 2014, unpublished). “For example, in a case such as this one, the dismissal served almost as a determination of the merits. The dismissal of [the] cyberstalking charge was expressly based on the fact that the district attorney had determined that there was ‘insufficient credible, admissible, reliable evidence remaining to support a continuation of the prosecution.'”

The Fifth Circuit addressed the Texas rules about settlement credits in two cases this summer:

1. Credit. An employee stole a number of checks by endorsing them to himself. The Court found “that the one satisfaction rule obtains . . ., for while there are multiple checks at issue, there is but a single injury.” Coastal Agricultural Supply, Inc. v. JP Morgan Chase Bank, N.A., No. 13-20293 (July 21, 2014). It then remanded for analysis of the appropriate allocation; a dissent would have dismissed this interlocutory appeal into a complex area of Texas law. The Court also affirmed that section 3.405 of the UCC — the “padded payroll” defense — provided an affirmative defense for the relevant bank to a common law claim for “money had and received.”

2. No credit. The victim of a fraudulent scheme sued the seller of the relevant business for breach of warranty, and the participants in the scheme for a fraudulent transfer. It settled with the seller and recovered a multi-million dollar judgment against the bank that participated in the transfer. Held, no credit for the bank: “Citibank’s alleged contractual breach and the TUFTA action against Worthington may share common underlying facts—the three fraudulent transfers from CitiCapital to Worthington totaling $2.5 million, induced by Wright & Wright. But such factual commonality does not suffice to count the contractual dispute’s settlement against TUFTA’s limit on recovery for a single avoidance ‘claim,’ Tex. Bus. & Comm. Code § 24.009(b), or to render Citibank a joint tortfeasor for one-satisfaction rule purposes.” GE Capital Commercial, Inc. v. Worthington National Bank, No. 13-10171 (June 10, 2014). The Court also held that Texas would apply an objective “good faith” test under its fraudulent transfer statute rather than a subjective test referred to in an older Texas Supreme Court opinion. (LTPC and this blog’s author represented the successful plaintiff/appellee in this case.)

The coverage dispute in Wiszia Co. v. General Star Indemnity Co. involved a lawsuit in which “Jefferson Parish essentially asserted Wisznia improperly designed a building and did not adequately coordinate with the builders during its construction.” No. 13-31125 (July 16, 2014). Reviewing the allegations under Louisiana’s eight-corners rule, and summarizing the extensive Louisiana jurisprudence on the topic, the Fifth Circuit found that the claim fell within the policy’s professional services exclusion. Under those authorities, mere use of the word “‘negligence’ is insufficient to obligate a professional liability insurer to defend the insured,” and “the factual allegations in the Jefferson Parish petition here do not give rise to an ordinary claim for negligence—such as an unreasonably dangerous work site.”

A subtle Erie issue flashed by when Andrews alleged premises liability claims against BP, and the Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for BP under a Texas statute. Terry v. BP Amoco, No. 12-40913 (June 27, 2014, unpublished). BP won summary judgment: “Exhibits C and D are the only evidence that Andrews identified as raising a material issue of fact as to BP’s responsibility for the explosion. Those exhibits are a Safety Bulletin issued by the United States Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board (CSB) and a CSB press release discussing the bulletin. The statute creating the CSB, however, prohibits Andrews from using the documents as evidence in this case. Additionally, both CSB documents also likely constitute inadmissible hearsay under the Federal Rules of Evidence.” The question not raised is how much substantive effect this type of federal statute must have in a state law tort claim, removed to federal court under diversity jurisdiction, so as to raise an Erie issue.

The plaintiffs in Garziano v. Louisiana Log Home, Inc. made 88 percent of the installment payments for a build-it-yourself log cabin kit, and then defaulted. No. 13-60291 (May 29, 2014, unpublished). The log cabin company won summary judgment against several contract and tort claims by the purchasers. Before final judgment was entered, however, it came to light that the company had resold several of the logs and actually was ahead on the transaction overall. The district court denied a Rule 59(e) motion about this information and entered judgment. The Fifth Circuit reversed, finding that the district court should not have focused on plaintiffs’ erroneous characterization of the issue as “unjust enrichment,” and by doing so, “essentially granted LLH an impermissible double recovery—making the earnest money provision an unenforceable penalty.” The Court remanded “with instructions for the district court to make findings on the amount of actual damages that LLH suffered and to amend the judgment to remit to the Garzianos any monies paid to LLH under the contract that were in excess of LLH’s actual damages.” (The defendant offers several packages for log homes, all of which look elegant and cost-effective to this author.)

The plaintiff in McKay v. Novartis, Inc. challenged the dismissal on preemption grounds, by an MDL court in Tennessee, of products liability claims about drugs made by Novartis. No. 13-50404 (May 27, 2014). The Fifth Circuit rejected an argument about inadequate time to get certain medical records, noting that the plaintiffs “sought formal discovery of evidence that was available to them through informal means” (citing other cases from the Court on that general topic), and also observing that two years passed from the filing of suit until Novartis sought summary judgment. The Court also affirmed the MDL court’s grant of summary judgment on Texas state law grounds about a breach of warranty claim, finding inadequate notice; as an Erie matter: “the majority of Texas intermediate courts have held that a buyer must notify both the intermediate seller and the manufacturer.”

At issue in Hess Management Firm, LLC v. Bankston were the damages arising from the termination of a contract about the operation of a gravel pit (sadly, not a magical gravel pit of rule-against-perpetuities lore). No. 12-31016 (April 18, 2014). The dispute was whether damages were capped at 180 days — the contract term for adequate notice of closure — or whether the closure of the pit was post-breach activity that is not relevant to damage calculation. The Fifth Circuit sided with the bankruptcy court and reversed the district court’s enlargement of the damages, concluding: “A contrary result would defeat the maxim of placing a non-breaching party in the same position they would have been had breach not occurred, and award [plaintiff] more than their expectation interest.”

A law firm argued that the Texas “anti-SLAPP” statute protected its efforts to solicit former patients of a dental clinic as clients. NCDR, LLC v. Mauze & Bagby PLLC, No. 12-41243 (March 11, 2014). (This statute has led to a great deal of litigation about communication-related disputes, often in areas that the Legislature may not have fully anticipated — this blog’s sister details such litigation in the Dallas Court of Appeals.) In a detailed analysis, the Fifth Circuit agreed that the district court’s ruling against the firm was appealable as a collateral order. The Court then sidestepped an issue as to whether the anti-SLAPP statute was procedural and thus inapplicable in federal court, finding it had not been adequately raised below. Finally, on the merits, the Court affirmed the ruling that the law firm’s activity fell within the “commercial speech” exception to the statute: “Ultimately, we conclude that the Supreme Court of Texas would most likely hold that M&B’s ads and other client solicitation are exempted from the TCPA’s protection because M&B’s speech arose from the sale of services where the intended audience was an actual or potential customer.”

Taylor sued his employer in state court for violations of Texas law. Taylor v. Bailey Tool & Manufacturing Co., No. 13-10715 (March 10, 2014). Later, he amended his pleading to add federal claims. Defendant removed and moved to dismiss on limitations grounds. Under Texas law, Taylor’s new claims would not relate back because the original state law claims were barred by limitations when suit was filed. Under Fed. R. Civ. P. 15(c), however, the claims would relate back because they “arose out of the conduct, transaction, or occurrence set out” in the original pleading. Noting that Rule 81(c) says the Federal Rules “apply to a civil action after it is removed,” the Fifth Circuit concluded that they did not “provide for retroactive application to the procedural aspects of a case that occurred in state court prior to removal to federal court.” Accordingly, it affirmed dismissal.

Mississippi law allows a “bad faith” claim relating to handling of workers’ compensation; Alabama law does not. Williams, a Mississippi resident, was injured in Mississippi while working for an Alabama resident contract. Williams v. Liberty Mutual, No. 11-60818 (Jan. 28, 2014). The Fifth Circuit reversed the choice-of-law question, finding that section 145 of the Restatement (governing tort claims) applied rather than other provisions for contract claims. Under that framework, Mississippi would give particular weight to the place of injury, and thus apply Mississippi law. The opinion highlights the importance of the threshold issue of properly characterizing a claim before beginning the actual choice-of-law analysis.

Boyett v. Redland Ins. Co. examined whether a forklift is a “motor vehicle” within the meaning of Louisiana’s uninsured motorist statute, and concluded that it is one. No. 12-31273 (Jan. 27, 2014). Its Erie analysis illustrates a feature of Louisiana’s civil law system that bedevils outsiders. On the one hand, a court “must look first to Louisiana’s Constitution, its codes, and statutes, because the ‘primary basis of law for a civilian is legislation, and not (as in the common law) a great body of tradition in the form of prior decisions of the courts.’ Unlike in common law systems, ‘[s]tare decisis is foreign to the Civil Law, including Louisiana.'” On the other hand, “[W]hile a single decision is not binding on [Louisiana’s] courts, when a series of decisions form a constant stream of uniform and homogenous rulings having the same reasoning, jurisprudence constante applies and operates with considerable persuasive authority.”

In Coleman v. H.C. Price Co., a toxic tort case, the Fifth Circuit certified to the Louisiana Supreme Court the question whether that state’s one-year limitations statute for survival actions is “prescriptive” (limitations does not run until the cause of action accrues, based on the plaintiff’s actual or constructive knowledge), or or “preemptive” (the cause of action is extinguished even if it has not accrued). No. 13-30150 (Dec. 18, 2013, unpublished). The issue is significant, as the opinion says: “the answer will define the time period governing all survival actions brought in Louisiana . . . .”

After a recent example of attorneys fees that were not “inextricably intertwined” under Texas law, the Fifth Circuit followed this month with a practical example of the Texas requirement of “presentment” of a contract claim before fees may be recovered. In Playboy Enterprises, Inc. Sanchez-Campuzano, the Court reminded that the pleading of presentment is procedural, and thus not a requirement in the federal system. No. 12-40544 (Dec. 23, 2013, unpublished). It is, however, a substantive requirement. In this case, sending a “Notice of Default” under a primary obligation was enough to “present” a claim for liability on a guaranty, noting the “flexible, practical understanding” of the requirement by Texas courts. The Court distinguished Jim Howe Homes v. Rodgers, 818 S.W.2d 901 (Tex. App.-Austin 1991, no writ), which found that service of a DTPA complaint was not presentment of a later-filed contract claim, on the ground that the “Notice” here went beyond mere service of a pleading. For thorough review of this principle, and other key points about fee awards, please consult the book “How to Recover Attorneys Fees in Texas” by my colleagues Trey Cox and Jason Dennis.)

While nominally about a limited issue of workers compensation law, Austin v. Kroger Texas LP analyzes basic issues of an “Erie guess,” Texas premises liability law, and the types of negligence claims available in Texas. No. 12-10772 (Sept. 27, 2013). Austin, a Kroger employee, slipped while cleaning an oily liquid with a mop. Contrary to store policy, a product called “Spill Magic” was not available to him that day. After a thorough discussion of the interplay between the common law of premises liability and the Texas workers compensation statutes (Kroger being a non-subscriber), the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment for Kroger that was based on Austin’s subjective awareness of the spill. “Section 406.033(a) of the Texas Labor Code takes the employee’s own negligence off of the table for a non-subscriber like Kroger . . . ” The Court went on to find fact issues about Kroger’s negligence in not having Spill Magic available, and about Kroger’s knowledge of the spill. The Court affirmed dismissal of the gross negligence claim, and in the remand, asked the district court to consider the specific type of negligence claim that Austin asserted under Texas law.

The insured estimated loss from a hailstorm at a shopping center at close to $1 million; the insurer estimated $17,000. TMM Investments v. Ohio Casualty Insurance, No. 12-40635 (Sept. 17, 2013). The insurer invoked its contractual right for an appraisal, which came in around $50,000. The insured sued, alleging that the appraisal improperly excluded damages to the HVAC system and that the panel exceeded its authority by considering causation issues. Applying State Farm Lloyds v. Johnson, 290 S.W.3d 886 (Tex. 2009), the Fifth Circuit agreed on the HVAC issue, but did not see that as a reason to invalidate the entire award, and reasoned that the appraisers were within their authority when they “merely distinguished damage caused by pre-existing conditions from damage caused by the storm . . . .”

In a high-profile “data breach” case, the district court dismissed several banks’ claims against a credit card processor after hackers entered its system and stole confidential information. Lone Star National Bank v. Heartland Payment Systems, No. 12-20648 (Sept. 3, 2013). The banks did not have a contract with the processor. They sought money damages for the cost of replacing compromised credit cards and reimbursing customers for wrongful charges. Applying New Jersey law, the Fifth Circuit found that the economic loss rule did not bar a negligence claim on these facts at the Rule 12 stage. These banks were an “identifiable class,” Heartland’s liability would not be “boundless” but run only to the banks, and the banks would otherwise have no remedy. The Court also noted that it was not clear whether the risk could have been allocated by contract. The Court declined to affirm dismissal on several other grounds such as choice-of-law and collateral estoppel, “as they are better addressed by the district court in the first instance.”

The plaintiffs in Young v. United States alleged that the Interior Department negligently prepared two studies which led to flooding along Interstate 12 in Louisiana, bringing federal litigation in 2008 when the last major flood was in 1983. No. 13-30094 (August 21, 2013). Plaintiff argued that the “continuing tort” doctrine saved the claim from limitations because the improperly-designed highway remained in place. The Fifth Circuit affirmed dismissal, noting two controlling Louisiana Supreme Court cases. The first, Hogg v. Chevron, involved leaking underground gasoline storage tanks and “rejected the plaintiffs’ contention that the failure to contain or remediate the leakage constituted a continuing wrong, suspending the commencement of the running of prescription . . . [explaining] that ‘the breach of a duty to right an initial wrong simply cannot be a continuing wrong that suspends the running of prescription, as that is the purpose of every lawsuit and the obligation of every tortfeasor.'” 45 So.3d 991 (La. 2010). Similarly, the second held: “[T]he actual digging of the canal was the operating cause of the injury[, and t]he continued presence of the canal and the consequent diversion of water from the ox-bow [were] simply the continuing ill effects arising from a single tortious act.” Crump v. Sabine River Authority, 737 So.2d 720 (La. 1999).

2013 has seen a steady stream of unpublished opinions favoring mortgage servicers, followed by a published opinion affirming a MERS assignment, and now a second published opinion rejecting arguments about the alleged “robosigning” of assignment documents. In Reinagel v. Deutsche Bank, a suit arising out of foreclosure on a Texas home equity loan, the Fifth Circuit held: (1) borrowers could challenge the validity of assignments to the servicer, since they were not asserting affirmative rights under those instruments; (2) alleged technical defects in the signature on the relevant assignment created rights only for the servicer and lender, not the borrower; (3) the assignment did not have to be recorded, mooting challenges to defects in the acknowledgement; and (4) a violation of the relevant PSA related to the transfer of the note did not create rights for the borrower. The opinion concluded with two important caveats: it was not deciding whether the Texas Supreme Court would adopt the “note-follows-the-mortgage” concept, and it reminded: “We do not condone ‘robo-signing’ more broadly and remind that bank employees or contractors who commit forgery or prepare false affidavits subject themselves and their supervisors to civil and criminal liability.” 735 F.3d 220 (5th Cir. 2013).

In Temple v. McCall, the Fifth Circuit confronted a series of property conveyances with ambiguous language about whether mineral rights were included. No. 12-30661 (June 20, 2013). The Court affirmed, approving the weight given by the district court to expert testimony about “customary interpretation” of similar deed language in Louisiana. The Court discussed the proper weight that Erie gives to an intermediate state appellate opinion, but ultimately found the relevant Louisiana case distinguishable on its facts. (The proper role of extrinsic evidence in contract cases is a recurring issue in the Court’s diversity cases, although the express finding of ambiguity in this dispute simplifed the analysis on that point.)

In its first published opinion of 2013 about the merits of a wrongful foreclosure claim, the Fifth Circuit rejected the plaintiff’s “show-me-the-note” and “split-the-note” arguments. Martins v. BAC Home Loans Servicing LP, 722 F.3d 249 (5th Cir. 2013). In footnote 2, the Court noted that much of the relevant law is federal because of diversity between the borrower and the foreclosing entity. As to the first theory, the court cited authority that allowed an authenticated photocopy to prove a note, and said: “We find no contrary Texas authority requiring production of the ‘original’ note.” As to the second, acknowledging some contrary authority, the Court reviewed the relevant statute and held: “The ‘split-the-note’ theory is . . . inapplicable under Texas law where the foreclosing party is a mortgage servicer and the mortgage has been properly assigned. The party to foreclose need not possess the note itself.” An unpublished opinion, originally released a day before Martins, was revised to closely follow its analysis and result. Casterline v. OneWest Bank, No. 13-50067 (revised July 5, 2013, unpublished).

On June 18, two separate panels — one addressing a chemical spill, the other a vessel crash into an oil well — reached the same conclusion in published opinions: when an insured fails to give notice within the agreed-upon period, as required by a “negotiated buyback” endorsement to a policy, the insurer does not have to show prejudice to void coverage. Settoon Towing LLC v. St. Paul Surplus Lines Ins. Co., No. 11-31030; Starr Indemnity & Liability Co. v. SGS Petroleum Service Corp., No. 12-20545. The notice provision was seen as part of the basic bargain struck about coverage. Both opinions — especially Starr, arising under Texas law — recognized the continuing viability of Matador Petroleum v. St. Paul Surplus Lines Ins. Co., 174 F.3d 653 (5th Cir. 1989), in this situation, notwithstanding later Texas Supreme Court cases requiring prejudice in other contexts arising from the main body of a policy. Settoon went on to address other issues under Louisiana insurance law, including whether the Civil Code concept of “impossibility,” which focuses on a failure to perform an obligation, applies to a failure to perform a condition precedent such as giving notice.

A lawyer’s letter making a settlement offer contained a paragraph accusing the other side of giving a witness money for favorable testimony. The accused party then sued for defamation. In Lehman v. Holleman, applying Mississippi law, the Fifth Circuit affirmed that such statements are absolutely privileged from liability because they are “plainly related” to an underlying judicial proceeding. No. 12-60814 (April 15, 2013, unpublished).

A company leased a railcar, and undertook to return it “cleaned of commodities,” which was defined to mean (among other things) “safe for human entry.” Sampson v. GATX Corporation, No. 12-30406 (March 19, 2013, unpublished). The district court concluded that this provision was only part of the contract devoted to allocation of the cost of cleaning. The Fifth Circuit disagreed, and found that the plaintiff had raised a fact issue about whether this contractual duty could give rise to tort liability to someone injured in the car, pursuant to section 324A of the Second Restatement of Torts.