Continuing an earlier post about how to sign documents, the issue of effective consent again appeared in Berry v. Fannie Mae, No. 14-10474 (April 17, 2015, unpublished). A mortgage servicer sent a trial payment plan to a borrower, which said: “This Plan will not take effect unless and until both the Lender and I sign it and Lender provides me with a copy of this Plan with the Lender’s signature.” Rejecting an argument that the servicer’s letter acknowledging the borrower’s signature waived this language, the Court enforced it and affirmed dismissal of the borrower’s claims. A similar analysis led to a similar result in Williams v. Bank of America, No. 14-20520 (May 7, 2015, unpublished).

Category Archives: Contracts

In Angus Chemical Co. v. Glendora Plantation, Inc., an industrial facility had an easement that gave it “the right to construct, maintain, inspect, operate, protect, alter, repair, replace and change” a pipeline. No. 14-30416 (March 24, 2015). The company plugged and abandoned its original 12″ pipeline in favor of a new 16″ one. The key appellate issue was whether the right to “replace” a pipeline allowed the company to simply substitute one pipeline for another, or whether it also “impl[ied] a corresponding duty to remove” the old one. The Fifth Circuit found the term “replace” was ambiguous in this context, and that there was a material fact issue in the extrinsic evidence about which meaning should prevail. Therefore, it reversed the district court’s summary judgment in favor of the chemical company. This topic — the role of extrinsic evidence in contract disputes — was most recently before the Court in a major case in the “Whoomp! There it is” litigation, and as detailed in a link from that post, frequently leads to disagreement between the trial courts and the Fifth Circuit.

In Angus Chemical Co. v. Glendora Plantation, Inc., an industrial facility had an easement that gave it “the right to construct, maintain, inspect, operate, protect, alter, repair, replace and change” a pipeline. No. 14-30416 (March 24, 2015). The company plugged and abandoned its original 12″ pipeline in favor of a new 16″ one. The key appellate issue was whether the right to “replace” a pipeline allowed the company to simply substitute one pipeline for another, or whether it also “impl[ied] a corresponding duty to remove” the old one. The Fifth Circuit found the term “replace” was ambiguous in this context, and that there was a material fact issue in the extrinsic evidence about which meaning should prevail. Therefore, it reversed the district court’s summary judgment in favor of the chemical company. This topic — the role of extrinsic evidence in contract disputes — was most recently before the Court in a major case in the “Whoomp! There it is” litigation, and as detailed in a link from that post, frequently leads to disagreement between the trial courts and the Fifth Circuit.

Fed. R. Civ. P. 60, titled “Grounds for Relief from a Final Judgment, Order, or Proceeding,” is generally invoked to vacate a judgment because of alleged misconduct, mistake, newly-discovered evidence, or other equitable reasons. Clause (5) of that rule also allows relief if “the judgment has been satisfied, released, or discharged; it is based on an earlier judgment that has been reversed or vacated; or applying it prospectively is no longer equitable.” That provision — and specifically, its rarely-litigated first clause — was at issue in Frew v. Janek, in which the Texas Health and Human Services Commission argued that it had fully performed under a consent decree related to the operation of a Medicaid program. No. 14-40048 (March 5, 2015). Construing the decree “according to ‘general principles of contract interpretation,'” and declining to apply the law of the case doctrine to the interpretation of the decree by the judge who entered the order, the Fifth Circuit found no error in the district court’s ruling that the defendants had complied with the order and performed fully.

Fed. R. Civ. P. 60, titled “Grounds for Relief from a Final Judgment, Order, or Proceeding,” is generally invoked to vacate a judgment because of alleged misconduct, mistake, newly-discovered evidence, or other equitable reasons. Clause (5) of that rule also allows relief if “the judgment has been satisfied, released, or discharged; it is based on an earlier judgment that has been reversed or vacated; or applying it prospectively is no longer equitable.” That provision — and specifically, its rarely-litigated first clause — was at issue in Frew v. Janek, in which the Texas Health and Human Services Commission argued that it had fully performed under a consent decree related to the operation of a Medicaid program. No. 14-40048 (March 5, 2015). Construing the decree “according to ‘general principles of contract interpretation,'” and declining to apply the law of the case doctrine to the interpretation of the decree by the judge who entered the order, the Fifth Circuit found no error in the district court’s ruling that the defendants had complied with the order and performed fully.

The L/B Nicole Eymard (right) became stuck while servicing a well in the Gulf of Mexico. The owner of the boat sued the contractor that hired the boat, in addition to the well owner, and both were found liable for charter fees while the vessel was unable to move. The well owner obtained indemnity from the contractor because the contractor had agreed to indemnify it for

The L/B Nicole Eymard (right) became stuck while servicing a well in the Gulf of Mexico. The owner of the boat sued the contractor that hired the boat, in addition to the well owner, and both were found liable for charter fees while the vessel was unable to move. The well owner obtained indemnity from the contractor because the contractor had agreed to indemnify it for  claims “based upon personal injury or death or property damage or loss.” Unpaid charter fees are a “loss” within the meaning of that language, even without proof of damage to property. Offshore Marine Contractors, LLC v. Palm Energy Offshore, LLC, No. 14-30059 (March 2, 2015).

claims “based upon personal injury or death or property damage or loss.” Unpaid charter fees are a “loss” within the meaning of that language, even without proof of damage to property. Offshore Marine Contractors, LLC v. Palm Energy Offshore, LLC, No. 14-30059 (March 2, 2015).

Superior MRI Services sued for tortious interference with contract; the defendant argued that Superior lacked standing because it never acquired rights under the relevant contracts, and the Fifth Circuit agreed. Superior MRI Services, Inc. v. Alliance Imaging, Inc., No. 14-60087 (Feb. 18, 2015). The record showed that P&L Imaging, a bankruptcy debtor, listed “MRI service agreements” on its schedule of assignments to Superior, with an assignment date of October 1, 2011. Superior, however, did not exist as a legal entity until November 28, 2011. No evidence showed that Superior ratified the contract after its formation, and the Court was unwilling to accept Mississippi’s approval of Superior as a vendor as evidence of a ratification. The Court distinguished the recent case of Lexmark, Int’l v. Static Control Components, 134 S. Ct. 1377 (2014), as relating to another aspect of the standing requirement.

Superior MRI Services sued for tortious interference with contract; the defendant argued that Superior lacked standing because it never acquired rights under the relevant contracts, and the Fifth Circuit agreed. Superior MRI Services, Inc. v. Alliance Imaging, Inc., No. 14-60087 (Feb. 18, 2015). The record showed that P&L Imaging, a bankruptcy debtor, listed “MRI service agreements” on its schedule of assignments to Superior, with an assignment date of October 1, 2011. Superior, however, did not exist as a legal entity until November 28, 2011. No evidence showed that Superior ratified the contract after its formation, and the Court was unwilling to accept Mississippi’s approval of Superior as a vendor as evidence of a ratification. The Court distinguished the recent case of Lexmark, Int’l v. Static Control Components, 134 S. Ct. 1377 (2014), as relating to another aspect of the standing requirement.

In an earlier opinion, the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment in favor of an insured, finding a fact issue as to whether late notice caused prejudice to the carrier. “Berkley I,” Berkley Regional Ins. Co. v. Philadelphia Indemnity Ins. Co., 690 F.3d 342 (5th Cir. 2012). After further proceedings, the district court granted summary judgment to the carrier and the Court affirmed. “Berkley II,” Berkley Regional Ins. Co. v. Philadelphia Indemnity Ins. Co., No. 13-51180 c/w No. 14-50099 (Jan. 27, 2015, unpublished). The key issue was whether notice to the broker sufficed to give notice the the carrier; the Court reasoned that even if the broker had a limited agency relationship with the carrier, notice of claims fell outside its scope: “Under the 2002 Agreement, Philadelphia expressly allowed [Agent] to act as an insurance broker and sell Philadelphia policies as Philadelphia’s representative, subject to Philadelphia’s approval. The 2002 Agreement is silent as to whether [Agent] had the ability to accept notice of claims on behalf of Philadelphia. Thus, [Agent] did not have express authority to accept notice of claims.” For the same reasons, an implied agency theory was also rejected.

The insurance coverage case of Mt. Hawley Ins. Co. v. Advance Products & Systems, Inc. illustrates the recurring differences of opinion between the Fifth Circuit and district courts about contract ambiguity. 14-30068 (Jan. 27, 2015, unpublished). When APS made a claim on its commercial property policy with Mt. Hawley, APS’s recovery was limited by a “coinsurance provision” that applies if it “has not insured the full value of its income.” The parties differed on whether “income” referred to projected or actual net income; the district court found ambiguity, and the Fifth Circuit reversed: “Although APS has a point—the language used in calculating the coinsurance penalty is imprecise—it does not render the contract ambiguous.” Based on the relationship between this provision and other parts of the policy, and the general purposes of coinsurance clauses, the Court reversed a summary judgment for the insured.

The insurance coverage case of Mt. Hawley Ins. Co. v. Advance Products & Systems, Inc. illustrates the recurring differences of opinion between the Fifth Circuit and district courts about contract ambiguity. 14-30068 (Jan. 27, 2015, unpublished). When APS made a claim on its commercial property policy with Mt. Hawley, APS’s recovery was limited by a “coinsurance provision” that applies if it “has not insured the full value of its income.” The parties differed on whether “income” referred to projected or actual net income; the district court found ambiguity, and the Fifth Circuit reversed: “Although APS has a point—the language used in calculating the coinsurance penalty is imprecise—it does not render the contract ambiguous.” Based on the relationship between this provision and other parts of the policy, and the general purposes of coinsurance clauses, the Court reversed a summary judgment for the insured.

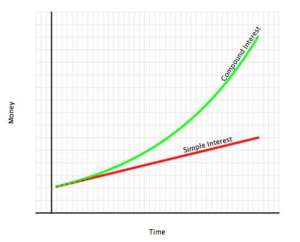

The note said: “So long as an Event of Default remains outstanding: (a) interest shall accrue at the Default Rate and, to the extent not paid when due, shall be added to the Principal Amount . . . .” The lender said this language meant that interest should be compounded, and the lower courts agreed — in the amount of almost $5 million. The borrower argued that this language only meant “that any unpaid interest will be added

The note said: “So long as an Event of Default remains outstanding: (a) interest shall accrue at the Default Rate and, to the extent not paid when due, shall be added to the Principal Amount . . . .” The lender said this language meant that interest should be compounded, and the lower courts agreed — in the amount of almost $5 million. The borrower argued that this language only meant “that any unpaid interest will be added

to the principal amount as the total debt due.” The Fifth Circuit disagreed, finding that this reading would impermissibly make the provision redundant “because it would operate only to label the accrued interest as money owed by [borrower] to [lender], and the interest was already owed. TCI Courtyard, Inc. v. Wells Fargo Bank, N.A., No. 14-10635 (Jan. 22, 2015, unpublished).

The case of AAA Bonding Agency v. United States Dep’t of Homeland Security involved the seldom-seen world of “immigration bonds” — a type of surety bond that allows release of an alien from custody while deportation proceedings are ongoing. No. 14-20057 (Jan. 12, 2015, unpublished). The Fifth Circuit has previously held that “DHS may only enforce an immigration bond against a surety company or bonding agent that has received notice demanding delivery of the alien covered by the bond.” This case involved 23 bonds where (1) AAA, the bonding agency, was liable on the bond with Surety National, an insurance company, (2) only AAA had received notice from DHS, and (3) Surety National had settled with DHS, and as part of the settlement, agreed that AAA would not be liable to DHS on these bonds if a court held that AAA’s obligation was joint and several with Surety National’s. The Court concluded that its prior holding did not alter the joint and several liability of AAA and Surety National as set forth in the language of the bonds, and ruled for AAA.

The case of AAA Bonding Agency v. United States Dep’t of Homeland Security involved the seldom-seen world of “immigration bonds” — a type of surety bond that allows release of an alien from custody while deportation proceedings are ongoing. No. 14-20057 (Jan. 12, 2015, unpublished). The Fifth Circuit has previously held that “DHS may only enforce an immigration bond against a surety company or bonding agent that has received notice demanding delivery of the alien covered by the bond.” This case involved 23 bonds where (1) AAA, the bonding agency, was liable on the bond with Surety National, an insurance company, (2) only AAA had received notice from DHS, and (3) Surety National had settled with DHS, and as part of the settlement, agreed that AAA would not be liable to DHS on these bonds if a court held that AAA’s obligation was joint and several with Surety National’s. The Court concluded that its prior holding did not alter the joint and several liability of AAA and Surety National as set forth in the language of the bonds, and ruled for AAA.

The same week as  the en banc vote in the whooping crane litigation, the Fifth Circuit analyzed “Whoomp! (There It Is).” The unfortunate song has been mired in copyright infringement litigation for a decade; the district court entered judgment for the plaintiff for over $2 million, and it was affirmed in Isbell v. DM Records, Inc., Nos. 13-40787 and 14-40545 (Dec. 18, 2014). [The opinion notes: “The word “‘Whoomp!’ appears to be a neologism, perhaps a variant of ‘Whoop!,’ as in a cry of excitement.”]

the en banc vote in the whooping crane litigation, the Fifth Circuit analyzed “Whoomp! (There It Is).” The unfortunate song has been mired in copyright infringement litigation for a decade; the district court entered judgment for the plaintiff for over $2 million, and it was affirmed in Isbell v. DM Records, Inc., Nos. 13-40787 and 14-40545 (Dec. 18, 2014). [The opinion notes: “The word “‘Whoomp!’ appears to be a neologism, perhaps a variant of ‘Whoop!,’ as in a cry of excitement.”]

The main appellate issue was a variant of a frequently-litigated topic — the role of extrinsic evidence in contract interpretation. The assignment in question was governed by California law, which the Court found to “employ[] a liberal parol evidence rule” with respect to consideration of extrinsic evidence. The appellant argued that the district  court erred “in interpreting the Recording Agreement without asking the jury to make any findings on the extrinsic evidence.” The Court disagreed, finding that the record did not present “a question of the credibility of conflicting extrinsic evidence” (emphasis in original): “The only dispute is over the meaning of the Recording Agreement and the inferences that should be drawn from the numerous undisputed pieces of extrinsic evidence. This is a question of law for the court, not for a jury.”

court erred “in interpreting the Recording Agreement without asking the jury to make any findings on the extrinsic evidence.” The Court disagreed, finding that the record did not present “a question of the credibility of conflicting extrinsic evidence” (emphasis in original): “The only dispute is over the meaning of the Recording Agreement and the inferences that should be drawn from the numerous undisputed pieces of extrinsic evidence. This is a question of law for the court, not for a jury.”

As chronicled in the sister blog 600Commerce (following business cases in the Dallas Court of Appeals), the issue of whether a guarantor can waive the “fair market value” offset right provided by the Texas Property Code — a problem that arises frequently after foreclosure sales — was hotly-litigated until the Texas Supreme Court settled the matter in Moyaedi v. Interstate 35/Chisam Road, L.P, 438 S.W.3d 1 (Tex. 2014), finding that the right was waivable.

The Fifth Circuit acknowledged and applied that holding in Hometown 2006-1 1925 Valley View, LLC v. Prime Income Asset Management LLC, finding that the waiver there was even clearer than in Moyaedi. In Moyaedi, the guarantor waived “every . . . defense”; here, the guarantor waived “any . . . offset, claim or defense,” and the guaranty also had a provision saying: “Guarantor WAIVES each and every right to which it may be entitled by virtue of any suretyship law, including any rights it may have pursuant to . . . Section

51.005 of the Texas Property Code.” No. 14-10182 (Dec. 11, 2014, unpublished).

Sundown Energy could access its oil and gas production facility via the Mississippi River, but had to cross Haller’s land to access it from the highway. They litigated about Sundown’s rights and reached a settlement, which their counsel read into the record on the day set for trial. The Fifth Circuit found that the parties had reached a settlement, which the district court had the authority to enforce pursuant to their agreement. The Court reversed, though, as to the district court’s resolution of several logistical issues: “Here, the district court erred by imposing several terms which either conflicted with or added to the agreement read into the record by the parties. Although the parties gave the district court the authority to enforce and interpret the settlement agreement, the district court did not have the power to change the terms of the settlement agreed to by the parties.” Sundown Energy L.P. v. Haller, No. 13-30294 et al. (Dec. 8, 2014).

Can a note be endorsed with a photocopied signature? Yes. Whittier v. Ocwen Loan Servicing, LLC, No. 13-20639 (Dec. 3, 2014, unpublished) (citing Tex. Bus. & Com. Code § 1.201(b)(37)) (“Signed” includes using any symbol executed or adopted with present intention to adopt or accept a writing.”)

Can a note be endorsed with a photocopied signature? Yes. Whittier v. Ocwen Loan Servicing, LLC, No. 13-20639 (Dec. 3, 2014, unpublished) (citing Tex. Bus. & Com. Code § 1.201(b)(37)) (“Signed” includes using any symbol executed or adopted with present intention to adopt or accept a writing.”)

Can a “deed of trust . . . upon a homestead exempted from execution,” which “shall not be valid or binding unless signed by the spouse of the owner,” be signed in separate but identical documents? Yes. Avakian v. Citibank, N.A., No. 14-60175 (Dec. 9, 2014) (citing Duncan v. Moore, 7 So. 221, 221-22 (Miss. 1890)) (“There is much force in the  argument of defendant’s counsel that the statute does not require a joint deed of husband and wife for the conveyance of the husband’s homestead . . . that the substantial thing is the written evidence of such consent; and that this may be as certainly shown by a separate instrument as by signing the deed of the husband.”)

argument of defendant’s counsel that the statute does not require a joint deed of husband and wife for the conveyance of the husband’s homestead . . . that the substantial thing is the written evidence of such consent; and that this may be as certainly shown by a separate instrument as by signing the deed of the husband.”)

In tour de force reviews of Louisiana’s Civil Code and civilian legal tradition, a plurality and dissent — both written by Louisiana-based judges — reviewed whether a 1923 deed created a “predial servitude” with respect to a right of access. The deed at issue said: “It is understood and agreed that the said Texas & Pacific Railway Company shall fence said strip of ground and shall maintain said fence at its own expense and shall provide three crossings across said strip at the points indicated on said Blue Print hereto attached and made part hereof, and the said Texas and Pacific Railway hereby binds itself, its successors and assigns, to furnish proper drainage out-lets across the land hereinabove conveyed.”

In tour de force reviews of Louisiana’s Civil Code and civilian legal tradition, a plurality and dissent — both written by Louisiana-based judges — reviewed whether a 1923 deed created a “predial servitude” with respect to a right of access. The deed at issue said: “It is understood and agreed that the said Texas & Pacific Railway Company shall fence said strip of ground and shall maintain said fence at its own expense and shall provide three crossings across said strip at the points indicated on said Blue Print hereto attached and made part hereof, and the said Texas and Pacific Railway hereby binds itself, its successors and assigns, to furnish proper drainage out-lets across the land hereinabove conveyed.”

The analysis involved citation to the Revised Civil Code of Louisiana of 1870 (the Code in effect at the time of conveyance), the 1899 treatise Traité de Droit Civil-Des Biens, and the 1893 work, Commentaire théorique & pratique du code civil. Despite the arcane overlay, the opinions turn on practical observations. The plurality notes that the deed uses “successors and assigns” language only with respect to drainage — not access — while the dissent observes that a “personal” access right, limited only to the parties to the conveyance and that does not run with the land, is impractical. Franks Investment Co. v. Union Pacific R.R. Co., No. 13-30990 (Dec. 2, 2014).

A mortgage servicer sued two individuals, alleging a conspiracy to defraud; the defendants argued that the servicer lacked standing because the notes in question were not properly conveyed. The case settled during trial, and as part of the settlement “the parties stipulated to several facts, including the fact that the Trusts were the owners and holders of the Loans at issue.” An agreed judgment followed. BAC Home Loans Servicing, L.P. v. Groves, No. 13-20764 (Nov. 3, 2014, unpublished).

The defendants then moved to vacate under FRCP 60(b), arguing that the plaintiff lacked standing. The district court denied the motion and the Fifth Circuit affirmed. It first noted that “the court will generally enforce valid appeal waivers, [but] a party cannot waive Article III standing by agreement . . .” Further noting that “parties may stipulate to facts but not legal conclusions,” the Court held: “That is exactly what happened here. [Defendants] conceded facts that establish [plainitiff’s] status; thus, the district court appropriately reached the resulting legal conclusion that [plaintiff] has standing.”

EnCana Oil & Gas hired Seiber as a general contractor, who in turn hired Holt and TAUG as subcontractors. Seiber failed to make timely payments. EnCana interpleaded the funds at issue, and Seiber then filed for bankruptcy — before entry of a final order in the interpleader case. Holt Texas, Ltd. v. Zayler, No. 13-41153 (Nov. 3, 2014).

EnCana Oil & Gas hired Seiber as a general contractor, who in turn hired Holt and TAUG as subcontractors. Seiber failed to make timely payments. EnCana interpleaded the funds at issue, and Seiber then filed for bankruptcy — before entry of a final order in the interpleader case. Holt Texas, Ltd. v. Zayler, No. 13-41153 (Nov. 3, 2014).

Holt and TAUG alleged that they had materialmen’s liens under Texas law that removed the funds from Seiber’s bankruptcy estate; Seiber’s bankruptcy trustee argued that the filing of the interpleader action “automatically satisfied its liability to Seiber, thus transferring legal possession of the funds to Seiber and the bankruptcy estate.”

The Fifth Circuit disagreed with the trustee and reversed the bankruptcy court, reasoning: “If this were so, the interpleader would be the final judge of its own legal obligations relative to the dispute, by depositing a sum solely determined by it, washing its hands of any relationship to the dispute and walking away whistling Yankee Doodle.”

Uretek USA developed a process for pavement repair, which it sublicensed to Uretek Mexico under an agreement signed in 2003. In 2010, the principals of the two companies met to try and resolve disputes about that agreement and other business dealings. During the meeting, the parties initialed an amended sublicense agreement, and Uretek USA accepted four checks from Uretek Mexico with these amounts and memo lines:

- $10 “As per First Amendment to Sublicense Agreement”

- $76,950.90 for “Full Payment on Technical Assistance”

- $225,471.05 for “Full Payment on Royalties”

- $10 for “Full Release [Uretek USA] to [Uretek Mexico]

Uretek USA later sued to dispute the enforceability of the amendment. The jury found that Uretek USA ratified it by conduct, principally by cashing these checks. While Uretek USA made several arguments against that finding on appeal, the number of checks and specificity of the notations on them was sufficient to sustain the verdict. Uretek (USA), Inc. v. Ureteknologia de Mexico S.A. de C.V., No. 13-20430 (Oct. 29, 2014, unpublished).

Pioneer suffered an oil well blowout and paid millions to restore order. It sued for reimbursement under its umbrella policy and the Fifth Circuit affirmed judgment for the insurer, based largely on the broad language of the relevant exclusions. Pioneer Exploration LLC v. Steadfast Ins. Co., No. 13-30802 (Sept. 22, 2014). Pioneer argued that the “owned, rented or occupied” exclusion did not apply to a mineral lease. The Court disagreed, noting that the mineral lease gave Pioneer some control over surface land, and that the broad language of the exclusion reached activity associated with oil production (citing Aspen Ins. UK, Ltd. v. Dune Energy, Inc., No. 10-30335 (5th Cir. Nov. 8, 2010, unpublished)). Further, noting that Louisiana law allowed debate as to whether an “owned property” exclusion reached remediation costs incurred to minimize liability to third parties, the Court found that this exclusion “specifically excludes containment costs” (reviewing Norfolk Southern Corp. v. California Union Ins., 859 So. 2d 167 (La. App. 2003)).” Finally, as to another exclusion, the Court found that the insured could not meaningfully allocate expense “between controlling costs and plugging costs.”

This summer, the Fifth Circuit declined to apply the Texas “one satisfaction rule” in a fraudulent transfer case, where the plaintiff had also settled a contract dispute with the seller of the business involved in the transfer. GE Capital Commercial, Inc. v. Worthington National Bank, No. 13-10171 (June 10, 2014). The court returned to the one-satisfaction rule in Structural Metals, Inc. v. S&C Electric Co., in which the jury awarded roughly $300,000 for a breach of warranty (measured as the difference in value between the goods as received, and the goods as warranted). The plaintiff also received an insurance payment for fire damage involving the goods. Again, the Court declined to apply the rule, finding that the plaintiff had suffered two distinct injuries. No. 13-50332 (Oct. 6, 2014, unpublished). Interestingly, in both cases, the Court focused on the one-satisfaction rule rather than the closely-related doctrine of the collateral source rule.

Boxcars Properties, the operator of an apartment complex, sued its neighboring landowners West Hills Park and Home Depot in Texas state court, complaining about development activity that led to a “lack of lateral support” and made the complex uninhabitable. Williams v. Home Depot, Inc. (Sept. 22, 2014, unpublished). Boxcars settled with Home Depot and obtained a $2.4 million verdict against West Hills, which then filed for bankruptcy.

West Hills sought indemnity from Home Depot, and the district court and Fifth Circuit rejected its request. The indemnity provision contained an exclusion for “the tortious acts of . . . other parties” — such as West Hills. Noting that “[t]he express negligence doctrine alone may be sufficient to deny [debtor’s] claim,” the Court decided on the basis of issue preclusion, agreeing with the district court that “the negligence finding was essential to the judgment because only that finding allowed for the damages for improvements to land included in the state court verdict.”

In Ferrara Fire Apparatus, Inc. v. JLG Industries, Inc., the Fifth Circuit returned to ground surveyed by the American Law Institute’s Restatement (Third) of Restitution, which the Court recently visited in cases about a faithless employee and the payment of benefits to a seaman. Here, Gradall Industries manufactured a specialized boom called the “Strong Arm,” designed for firefighting, and Ferrara Fire Apparatus contracted to serve as its exclusive sales representative. The relationship soured, Gradall terminated the contract, and Ferrara sued. Ferrara obtained judgment for unjust enrichment for $1 million. The Fifth Circuit reversed, finding no evidence of “an absence of justification or legal cause for the enrichment” as required by Louisiana law: “Gradall was simply competing in the market, which it was entitled to do after ending its exclusive contract with Ferrara.” No. 13-30600 (Sept. 9, 2014, unpublished).

CAP agreed to sell a security to VPRO. Their contract said: “The purchase price is $400,000 and this amount is to be paid to you within 10 business days from the date of transfer of the [security t]o: CITIBANK NY DTC 908 Account 089154 CSC73464, Further Credit to: [CAP], Beneficiary Deposit Account NR. 840 BSI SPA San Marino.” Collective Asset Partners, LLC v. Vtrader Pro, LLC, No. 13-20619 (Aug. 15, 2014, unpublished).

CAP hired a broker, who successfully transferred the security to the DTC account but, because the broker provided inaccurate information, failed to transfer it on to the San Marino account. VPRO refused to pay. CAP sold the security to another buyer for $175,069.41 and sued VPRO for the difference.

Applying Texas law, the Fifth Circuit agreed with the district court that VPRO unambiguously had no payment obligation until both transfers occurred, noting both the “Further Credit to” language in the contract, and the fact that the broker in fact tried to make both transfers.

The trustee of a litigation trust formed from the bankruptcy of Idearc, Inc. sued its former parent, Verizon, alleging billions of dollars in damages in connection with its spinoff. After a bench trial and several other orders, the district court ruled in favor of defendants, and the Fifth Circuit affirmed in U.S. Bank, N.A. v. Verizon Communications, No. 13-10752 (revised Sept. 2, 2014).

The opinion, while lengthy, still only hints at the complexity of the case, and much of its analysis is fact-specific. Some of the issues addressed include:

1. A bankruptcy litigation trust does not have a right to jury trial on a fraudulent transfer claim, when the defendant creditor has filed a proof of claim in the bankruptcy, and the bankruptcy court must resolve whether a fraudulent transfer occurred to rule on that claim (analyzing and applying Langemkamp v. Culp, 498 U.S. 42 (1990), in light of Stern v. Marshall, 131 S. Ct. 2594 (2011)).

2. In the context of determining whether the district court reviewed an earlier ruling correctly, on pages 26-27, the Court provided crisp definitions of the basic concepts of dictum and holding.

3. In the course of rejecting an argument about the refusal to admit several pieces of evidence, the Court noted that the trustee “does not discuss how each specific piece of evidence was likely to affect the outcome of the trial, in light of all the evidence presented.”

4. A defense expert, without experience in the particular industry, was still qualified to speak to valuation methodology in the bench trial, and “we cannot reverse the district court for adopting one permissible view over the other.”

5. The Court thoroughly reviewed the fiduciary duties owed from a parent to a subsidiary under Delaware law, while affirming the district court’s conclusions about causation associated with their alleged breach.

One party to a settlement made the last installment payment several weeks late, triggering an acceleration clause that led to more liability. Celtic Marine Corp. v. James C. Justice Co., No. 13-30712 (July 29, 2014). The parties had this email exchange after the last payment was due and before it was made, which the party in default said modified the agreement:

A (1-5-2013): Are we being paid the $91,666.66 to settle this once and for all? I have lost faith in the agreement from your side.

A (1-7-2013): Are you paying us the $91,666.66 today?

B(1-7-2013): Fri

A (1-7-2013): o/n check correct and can’t u do it Thurs for Friday devl?

The Fifth Circuit held that this exchange did not modify the agreement, for several reasons: (1) the parties had not agreed to conduct transactions by electronic means [citing Louisiana’s version of the Uniform Electronic Transactions Act], (2) prior contracts had been “typed agreements physically signed,” and (3) factually, the email that talks about payment “to settle this for once and for all” was 1 of 15 demands for payment in a “one-sided” set of communications.

After recently reviewing the phrase “computed at the mouth of the well,” the Fifth Circuit returned to oil royalties in Potts v. Chesapeake Exploration LLC, No. 13-10601 (July 29, 2014). The lease fixed the royalty as a percentage of “the market value at the point of sale,” and would be “free and clear of all costs and expenses related to the exploration, production and marketing of oil and gas production . . . ” Since Chesapeake’s sales of gas occured at the wellhead, this language allowed it to deduct a reasonable post-production cost for delivering the gas from the wellhead under Heritage Resources, Inc. v. NationsBank, 939 S.W.2d 118 (Tex. 1996). The Court said that its conclusion was not affected, under the terms of this lease, by the fact that Chesapeake sold to an affiliate. The Court also rejected a procedural argument about whether Heritage was binding precedent after the Texas Supreme Court’s 4-4 vote on rehearing.

A 1404(a) dispute was affirmed in Empire Indemity Ins. Co. v. N-S Corp., where “almost all non-party witnesses and all sources of proof needed to determine whether damages were covered by Empire’s policy are in, or around, Texas, and subject to the district court’s compulsory subpoena power.” No. 13-40426 (June 12, 2014, unpublished). On the merits, an aggrieved car wash operator sued its parts supplier and won a verdict for over $3 million. Several months later, the parts supplier and its primary carrier settled with the plaintiff, all parties mutually released all claims against each other, and the parts supplier assigned its claims against its excess carrier to the plaintiff. The excess carrier won summary judgment and the Fifth Circuit affirmed: “Following a release, the releasor cannot sue the releasee’s insurer ‘because the release precludes the prerequisite determination of [releasee’s liablity.'” (quoting Angus Chem. Co. v. IMC Fertilizer, Inc., 939 S.W.2d 138 (Tex. 1997)).

Chesapeake’s lease obliged it to pay the Warrens a royalty based on “the amount realized by Lessee, computed at the mouth of the well.” A lease addendum said the royalty “shall be free of all costs and expenses related to the exploration, production, and marketing . . . including, but not limited to, costs of compression, dehydration, treatment and transportation.” Warren v. Chesapeake Exploration LLC, No. 13-10619 (July 16, 2014).

The addendum went on to say that “Lessor will, however, bear a proportionate part of all those expenses imposed upon Lessee by its gas sales contract to the extent incurred subsequent to those that are obligations of Lessee.” The Warrens contended that this sentence defined certain shared expenses which should not have been deducted from the royalty. The Fifth Circuit disagreed and affirmed the Rule 12 dismissal of their complaint, finding that the sentence only referred to “the cost of delivering marketable gas to a sales point other than the mouth of the well.” (distinguishing Heritage Resources, Inc. v. NationsBank, 939 S.W.2d 118 (Tex. 1996)).

The Court reversed, however, as to another pair of plaintiffs with a different lease addendum. Noting simply that it was different, the Court found that their claim should not have been dismissed, as “[i]t is not apparent from the face of the complaint or its attachments that they could not conceivably state a cause of action.”

In Bluebonnet Hotel Ventures, LLC v. Wells Fargo Bank, N.A., the Fifth Circuit considered whether there had been an “[e]rror that vitiates consent” because of a “failure of cause” about an interest rate swap agreement, so as to allow its cancellation under Louisiana contract law. No. 13-30827 (June 6, 2014). In the course of affirming summary judgment for the bank, the Court declined to consider emails written around the time of contracting, noting: “Under Louisiana law, courts may only consider parol evidence when a contract is ambiguous.” To illustrate the sharp edge that separates holdings in the area of extrinsic evidence, cf. Fruge v. Amerisure, 663 F.3d 743 (5th Cir. 2011) ( applying Louisiana law and holding: “Parol evidence is admissible to show mutual error even though the express terms of the policy are not ambiguous.”) (citations omitted).

First case: Highland Capital sued Bank of America for the alleged breach of an oral contract to sell a $15.5 million loan. After the Fifth Circuit reversed the dismissal of this claim under Rule 12(b)(6), it affirmed summary judgment for the defendant in Highland Capital Management LP v. Bank of America, No. 13-11026 (July 3, 2014). Highland relied upon standard terminology promulgated by an industry association, while the Bank pointed to evidence showing that, in this specific transaction, the Bank was not familiar with that terminology and not want it to control. “Although industry custom is extrinsic evidence a factfinder can use to determine the parties’ intent to be bound, its value is substantially diminished where, as here, other evidence overwhelmingly shows that the persons involved in the dealings were unaware of those customs.” The Court also rejected an alternative theory that a prior transaction that involved the terminology continued to govern the parties’ relationship, noting: “Whether a prior contract had a binding effect on the procedures available for future contract-formation is a legal question.”

Second case: As with the previous case, WH Holdings LLC v. Ace American Ins. Co. was remanded for development of a factual record, this time for extrinsic evidence about a contract ambiguity. No. 13-30676 (June 26, 2014, unpublished). And as with the previous case, the Fifth Circuit affirmed a summary judgment, finding that seven pieces of extrinsic evidence were either not relevant to the specific contract issue, or “equally consistent with both” readings.

The agreed protective order said: “At any time after the delivery of documents designated ‘confidential,’ counsel for the receiving party may challenge the confidential designation of any document or transcript (or portion thereof) by providing written notice thereof to counsel for the opposing party.” The producing party then has 15 days to seek protection; if it does not do so, “then the disputed material shall no longer be subject to protection as provided in this order.” Moore v. Ford Motor Co., No. 13-40761 (June 20, 2014).

Pursuant to the order, Ford produced four boxes of documents related to Volvo safety issues. These communications ensued:

- On May 11, 2004, plaintiffs’ counsel emailed to challenge the confidentiality designations of several documents.

- On June 4, Ford’s counsel asked for Bates numbers.

- On June 23, plaintiffs’ counsel responded, expanded on the confidentiality argument, and said it “will begin passing them out to any and everyone that is interested”

- In July, plaintiffs’ counsel asked: “what’s the word . . . on confidentiality?”

- The next day, Ford’s counsel withdrew its designations as to some documents, said it was “evaluating your claims” as to others, and “expects you to abide by the terms of the Protective Orders in the meantime”

- Plaintiffs’ counsel responded: “I gave Ford adequate time. I am sending the materials out. Thanks for trying.” (He did not specify what “materials”)

- On February 22, 2005, plaintiffs’ counsel asked for an update on the “confidentiality issue”

- On March 8, 2005, Ford responded that “in the spirit of cooperation” it would “officially de-designate from the Protective Order” specified other documents.

In 2012, documents surfaced in other litigation that Ford had produced pursuant to the above protective order; while the opinion does not specify what they were, it seems clear that they were documents which Ford had not formally “de-designated.” Ford moved to enforce the protective order and the district court agreed, finding no “clear written notice . . . challenging the confidential designation of these documents.”

On appeal, plaintiffs argued that the 15-day period ran from the first email, and Ford thus waived its designations by not moving for protection. The Fifth Circuit disagreed, finding the protective order ambiguous on this issue, and stating: “This interpretation may well be the better reading without more, but the parties understanding of these agreed orders bears upon the interpretation, and the actions of both parties strongly suggest” otherwise, noting the lengthy dialogue between the parties. Noting that “[a]lthough on de novo review a different outcome may obtain,” the Court found the district court’s conclusion that no waiver occurred to not be clearly erroneous.

A dissent, among other arguments, noted that (1) the 15-day provision only requires that confidentiality be “in dispute,” (2) Ford drafted the agreement so any ambiguity should be construed against it, and (3) Ford had the burden to establish confidentiality. The dissent concluded the majority opinion undermined “efficient resolution of discovery disputes” by allowing “Ford . . . to undermine this purpose through vague, non-responsive answers.”

The plaintiff in McKay v. Novartis, Inc. challenged the dismissal on preemption grounds, by an MDL court in Tennessee, of products liability claims about drugs made by Novartis. No. 13-50404 (May 27, 2014). The Fifth Circuit rejected an argument about inadequate time to get certain medical records, noting that the plaintiffs “sought formal discovery of evidence that was available to them through informal means” (citing other cases from the Court on that general topic), and also observing that two years passed from the filing of suit until Novartis sought summary judgment. The Court also affirmed the MDL court’s grant of summary judgment on Texas state law grounds about a breach of warranty claim, finding inadequate notice; as an Erie matter: “the majority of Texas intermediate courts have held that a buyer must notify both the intermediate seller and the manufacturer.”

In Songcharoen v. Plastic & Hand Surgery Associates, the district court denied cross-motions for summary judgment about the meaning of a contract and had a trial as to the terms it believed to be ambiguous. No. 13-60315 (April 2, 2014, unpublished). Even though both matters present a common issue of law, because “the ‘evidence’ presented at pretrial may well be different from the evidence presented at trial,” the Court reviewed the issue through review of the denial for judgment as a matter of law. The Court reminded: “because Rule 50 motions for judgment as a matter of law are not required following a bench trial, reviewing a district court’s denial of summary judgment is appropriate following a bench trial.” (citing Black v. J.I. Case Co., 22 F.3d 568, 570 (5th Cir. 1994), and Becker v. Tidewater, Inc., 586 F.3d 358, 365-66 n.4 (5th Cir. 2009)).

The defendant in Advanced Nano Coatings, Inc. v. Hanafin “entered into an employment agreement with [plaintiff] in which [defendant] agreed to devote 100% of his professional time and effort to [plaintiff] or its subsidiary . . . .” No. 13-20109 (Feb. 19, 2014, unpublished). “The district court . . . found that Hanafin breached his fiduciary obligations . . . a finding Hanafin does not dispute on appeal.” Quoting ERI Consulting Engineers v. Swinnea, 318 S.W.3d 867, 872 (Tex. 2010), the Fifth Circuit noted that under Texas law, “if the fiduciary . . . acquires any interest adverse to his principal, without a full disclosure, it is a betrayal of his trust and a breach of confidence, and he must account to his principal for all he has received.” The Court then held: “Accordingly, [defendant’s] breach of fiduciary duties obligates him to repay everything he gained by virtue of his position, including payments for his salary and any expenses he may have incurred.”

A restaurant showed the pay-per-view broadcast of a boxing championship without the approval of the holder of the licensing rights. J&J Sports Productions, Inc. v. Mandell Family Ventures, LLC, No. 13-10485 (May 2, 2014). The licensor sued the restaurant under the Federal Communication Act, and the district court granted summary judgment to the licensor for $350 in statutory damages and $26,730.30 in attorneys fees. The Fifth Circuit reversed, reviewing two issues. First, as to the licensor’s claim under section 553 of the Act, the Court found a fact issue as to whether the restaurant had been “specifically authorized . . . by a cable operator” to make the showing, which would bring the restaurant within a statutory safe harbor. The Court reviewed affidavit testimony of the cable company that at least showed “the Defendants did not steal, intercept, or obtain the broadcast under false pretenses.” Second, the Court rejected a claim based on section 605 of the Act, finding it limited to radio communications only (thereby siding with the Third Circuit in a split with the Seventh about the applicability of that section to cable television).

The Fifth Circuit released a slightly revised opinion in Excel Willowbrook LLC v. JP Morgan Chase Bank, No. 12-20367 (revised April 24, 2014), a dispute about the FDIC’s rights upon assigning the assets of a failed bank. Of particular interest is the new footnote 34, which observes: “[T]he continued vitality of prudential ‘standing’ is now uncertain in the wake of the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Lexmark International, Inc. v. Static Control Components, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 1377 (2014). See id. at 1388 (‘[A] court . . . cannot limit a cause of action . . . merely because “prudence” dictates.’).”

1. The Fifth Circuit vacated its panel opinion in Sawyer v. duPont to certify two questions to the Texas Supreme Court — paraphrased slightly, they were (1) whether an at-will employee can sue for fraud for loss of employment, and (2) whether a 60-day “cancellation-upon-notice” collective bargaining agreement would change a “no” answer to (1). The Texas Supreme Court has now answered those questions: “no” as to the basic question about a fraud claim arising from at-will employment, and “in the situation presented, no” to the second question about the effect of the CBA. “The Employees argue that it would contravene public policy to allow an employer to benefit from its duplicity, but public policy is not better served by allowing contracting parties to circumvent their agreement.” No. 12-0626 (Tex. April 25, 2014). (The Fifth Circuit formally adopted that reasoning and affirmed on June 11, 2014).

2. Similarly, the Court vacated its panel opinion in Ewing Construction v. Amerisure Insurance Corp. to certify the question whether a CGL policy’s “Contractual Liability Exclusion” would reach a contract in which a contractor commits to work in a “good and workmanlike manner.” The Texas Supreme Court answered “no”: “[A] general contractor who agrees to perform its construction work in a good and workmanlike manner, without more, does not enlarge its duty to exercise ordinary care in fulfilling its contract, thus it does not ‘assume liability’ for damages arising out its defective work so as to trigger the Contractual Liability Exclusion.” No. 12-0661 (Tex. Jan. 17, 2014). The opinion has been called a “significant reassurance” to policyholders in the construction business.

The plaintiff in Jonibach Management Trust v. Wartburg Enterprises sued the defendant for breach of an oral contract; specifically, an agreement to exclusively market the plaintiff’s products in the US. No. 13-20308 (April 24, 2014). The defendant made three counterclaims, two of which were dismissed because they relied on an additional oral modification to the contract and could not satisfy the Statute of Frauds. The third survived before the Fifth Circuit, however, as it was essentially the mirror image of the plaintiff’s claim — contending that the plaintiff wrongfully supplied goods to other distributors. Among other reasons for that conclusion, the Court noted that the plaintiff’s “pleadings and testimony regarding the initial contract . . . constitute judicial admissions,” and reviewed the elements of such an admission.

At issue in Hess Management Firm, LLC v. Bankston were the damages arising from the termination of a contract about the operation of a gravel pit (sadly, not a magical gravel pit of rule-against-perpetuities lore). No. 12-31016 (April 18, 2014). The dispute was whether damages were capped at 180 days — the contract term for adequate notice of closure — or whether the closure of the pit was post-breach activity that is not relevant to damage calculation. The Fifth Circuit sided with the bankruptcy court and reversed the district court’s enlargement of the damages, concluding: “A contrary result would defeat the maxim of placing a non-breaching party in the same position they would have been had breach not occurred, and award [plaintiff] more than their expectation interest.”

The Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment on a construction subcontractor’s promissory estoppel claim in MetroplexCore, LLC v. Parsons Transportation, No. 12-20466 (Feb. 28, 2014). The Court noted the specificity of the statements made to it by representatives of the general contractor, the parties’ relationship on an earlier phase of the project, and specific communications describing reliance. The Court relied heavily on the analysis of a similar claim in Fretz Construction Co. v. Southern National Bank of Houston, 626 S.W.2d 478 (Tex. 1981).

The question in Bank of New York Mellon v. GC Merchandise Mart LLC was whether the acceleration of a note triggered a $1.8 million prepayment penalty, when the debtor had ceased making payments on the note. No. 13-10461 (Jan. 27, 2014). The Fifth Circuit affirmed judgment in favor of the debtor: “The plain language of the contract does not require the payment of the Prepayment Consideration in the event of mere acceleration. Quite the opposite, in fact: the plain language plainly provides that no Prepayment Consideration is owed unless there is an actual prepayment, whether voluntary or involuntary.”

After WaMu failed, the FDIC conveyed its assets and liabilities to Chase. Several landowners sought to enforce lease terms against Chase by virtue of that conveyance. The Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for them in Excel Willowbrook LLC v. JP Morgan Chase Bank, NA, 758 F.3d 592 (5th Cir. 2014). First, the Fifth Circuit “reluctantly” followed two other Circuits which found that a “no-beneficiaries” clause in the FDIC’s assignment extinguished the landlords’ rights, noting its own belief that the lease requirements were more in the nature of primary obligations. But the Court then agreed with the district court that the landlords were in privity of estate with Chase and could enforce the leases for that reason, characterizing the FDIC’s argument to the contrary as “ignor[ing] eight centuries of legal history,” and expressly disagreeing with an Eleventh Circuit case to the contrary. As for concerns about expansive liability for FDIC assignees, the Court observed: “The FDIC can avoid its present plight in future cases by drafting contractual provisions for the right it seeks to claim.” The Court re-examined this “obscure but heavily litigated consequence of the largest bank failure in U.S. history” in Central Southwest Texas Development, LLC v. JPMorgan Chase, No. 12-51083 (March 2, 2015), resolved largely on procedural grounds.

Waltner v. Aurora Loan Services LLC welcomes the New Year with three bread-and-butter issues in business litigation. No. 12-50929 (Dec. 31, 2013, unpublished). First, a party’s failure to answer on time does not require the “drastic remedy” of a default judgment, especially when a plaintiff shows no prejudice from the failure to timely answer. The granting of a default judgment is a discretionary ruling by the district court. Second, damages for lost use of property are not reliance damages that can be recovered with a promissory estoppel claim. Rather, they are consequential losses — a form of expectation damages. Finally, while Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(g)(2) says that a court “must strike” unsigned discovery responses “unless a signature is promptly supplied” after the error is identified, the district court has discretion in determining what is “prompt” and in what weight to give the lack of prejudice to the opposing party.

The parties’ agreement said: “Upon payment of the Lease Termination Fee, TTE will not longer have any obligations under Section 9.1A.” The district court found that the structure of the agreement meant that provision did not apply to all of the relevant buildings. The Fifth Circuit disagreed: “While such a divisions may be analytically satisfying, it is unsupported by any other language in the MOU, such as, for example, a paragraph heading identifying a particular provision as only relating to one warehouse.” APL Logistics Americas, Ltd. v. TTE Technology, Inc., No. 13-10352 (Dec. 13, 2013, unpublished).

Among other issues in Farkas v. GMAC Mortgage LLC, a borrower disputed whether he had received proper notice of the servicer’s identity, arguing that only the current mortgagee could send effective notice. No. 12-20668 (Dec. 2, 2013, unpublished). The Fifth Circuit affirmed a judgment against him on the grounds of quasi-estoppel, noting: “The duration and regularity of these continued payments to mortgage servicers who had not been identified by current mortgagees constitute acquiescence to the validity of notice of transfer from one mortgage servicer to the next. The equitable relief afforded by quasi-estoppel assures that a party’s position on a given issue is more than a matter of mere convenience but is instead a stance to which it is bound.”

Seventy property owners sued St. Bernard Parish, alleging that it wrongfully demolished their properties in the wake of Hurricane Katrina (which flooded virtually every structure in that hard-hit area). The Parish’s insurer disputed coverage. Lexington Ins. Co. v. St. Bernard Parish Gov’t, No. 13-30300 (Dec. 6, 2013, unpublished). Among other arguments, the insurer argued that there was no coverage because the policy had a $250,000 retention limit per occurrence, and each demolition (none of which involved more than that amount) should be viewed as a separate occurrence. The district court and Fifth Circuit ruled for the Parish. The Fifth Circuit noted that the limit applied “separately to each and every occurrence . . . or series of continuous, repeated, or related occurrences,” and that the phrase “related” has a broad meaning in the insurance context, covering logical or causal connections between acts or occurrences. Here: “[T]he acts alleged in the underlying actions are related because they all resulted from St. Bernard’s ordinance condemning those properties that remained in disrepair following Hurricane Katrina. The fact that the properties in the underlying action were demolished at different times, in varying degrees, and at different locations, does not mean that these acts are not related.”

The plaintiff in Weeks Marine Inc. v. Standard Concrete Products Inc. fell from a crane during a bridge construction project. No. 12-20610 (Dec. 6, 2013). He sued Weeks Marine, the general contractor, who in turn sought indemnity from Standard Concrete, the manufacturer of the “concrete fender modules” for the project. The district court granted summary judgment for the manufacturer and the Fifth Circuit affirmed. A broader indemnity obligation in the original purchase order was limited by the additional terms and conditions to “actual damages relating to workmanship of Seller’s (Standard Concrete) product.” Accordingly, the plaintiff’s claims, related to a steel component of the product made by another company, were not covered: “The steel modules are a component that Standard Concrete used to make its product; they are not the product itself. Standard Concrete’s products are the pre-cast concrete fender modules. The common usage of ‘product’ distinguishes this term from components, tools, and equipment used in the manufacturing process.”

The Fifth Circuit continued its conservative approach to the construction of guaranties in McLane Foodservice Inc. v. Table Rock Restaurants, LLC, No. 12-50980 (Nov. 15, 2013). In 1997, an investor in a restaurant chain guaranteed the chain’s debts to PFS, a division of Pepsioco. Years later, McLane became the owner of PFS’s operations after a series of sales transactions. In 2010, a customer of McLane called Table Rock went out of business, owing McLane over $400,000, and sought to collect on the original guaranty. The Fifth Circuit agreed with the district court that the guaranty only reached credit extended by PFS, that McLane was not an “affiliate” of PFS, and that “successors and assigns” language in the guaranty could not expand the scope of the underlying guaranty obligation.

A subcontractor’s policy excluded “property damage” to “your work.” An endorsement added the general contractor as an additional insured “only with respect to liability for . . . ‘property damage’ . . . caused, in whole or in part, by . . . [y]our acts or omissions.” “The policy defined “you” and “your” with reference to the subcontractor and the endorsement did not purport to modify that definition. State Farm Auto Ins. v. Harrison County, No. 13-60001 (Sept. 16, 2013, unpublished). The insurer argued that the additional insured could only “stand[] in shoes no larger than those worn by the primary policyholder.” The Fifth Circuit did not disagree, but found that this specific endorsement created ambiguity when read along with the original policy, and thus affirmed the district court’s summary judgment in favor of coverage.

In an unpublished opinion that happened to come out the same day as the slightly-revised “robosigning” opinion of Reinagel v. Deutsche Bank, the Fifth Circuit briefly reviewed the requirements for a summary judgment affidavit in a note case. RBC Real Estate Finance, Inc. v. Partners Land Development, Ltd., No. 12-20692 (Oct. 30, 2013, unpublished). As to foundation, the affidavit purported to be based on personal knowledge, and said that “[a]s an account manager at RBC[, the witness] is responsible for monitoring and collecting the . . . Notes.” “Therefore, [he] is competent to testify on the amounts due . . . .” As to sufficiency, the Court quoted Texas intermediate appellate case law: “A lender need not file detailed proof reflecting the calculations reflecting the balance due on a note; an affidavit by a bank employee which sets forth the total balance due on a note is sufficient to sustain an award of summary judgment.”

CHS Inc. v. Plaquemines Holdings LLC presented the interaction of the Bankruptcy Code and an old section of the Louisiana Civil Code (involving cases from 1849, 1828, and 1913). No. 13-30028 revised (Nov. 26, 2013). The Louisiana Code provision provides: “When a litigious right is assigned, the debtor may extinguish his obligation by paying to the assignee the price the assignee paid for the assignment, with interest from the time of the assignment.” As the Fifth Circuit noted: “The law is aimed at preventing unnecessary litigation by reducing the ability of third parties to buy and sell legal claims for profit.” CHS, part owner of a tract of land along with a bankrupt company, attempted to redeem that company’s interest after it was sold as part of a dissolution case required by the bankruptcy. The Court found that the sale, conducted pursuant to bankruptcy court orders, fell within a “judicial sale” exception to the Code provision that prevented CHS from using it here.