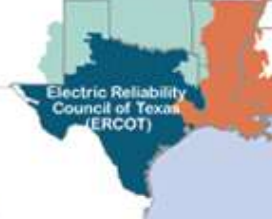

It’s been a busy fall for the Dormant Commerce Clause. In addition to the Fifth Circuit’s recent invalidation of a Texas law about the ownership of electricity-generation facilities, the Court also struck down a New Orleans residency requirement for the ownership of Vrbo-type rental properties:

It’s been a busy fall for the Dormant Commerce Clause. In addition to the Fifth Circuit’s recent invalidation of a Texas law about the ownership of electricity-generation facilities, the Court also struck down a New Orleans residency requirement for the ownership of Vrbo-type rental properties:

The district court held that the residency requirement discriminated against interstate commerce. That was the right call. But the court then applied the Pike test [for an incidental effect] to uphold the law. That was a mistake; it should have asked whether the City had reasonable nondiscriminatory alternatives to achieve its policy goals. Because there are many such alternatives, the residency requirement is unconstitutional under the dormant Commerce Clause.

Hignell-Stark v. City of New Orleans, No. 21-30643 (Aug. 22, 2022).