An earlier panel opinion found the Golf Channel liable for $5.9 million under the Texas Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Act (“TUFTA”), even though it delivered airtime with that market value, because the purchaser was Allen Stanford while running a Ponzi scheme. Accordingly, the airtime had no value to creditors, despite its market value. On rehearing, the Fifth Circuit vacated its initial opinion and certified the controlling issue to the Texas Supreme

An earlier panel opinion found the Golf Channel liable for $5.9 million under the Texas Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Act (“TUFTA”), even though it delivered airtime with that market value, because the purchaser was Allen Stanford while running a Ponzi scheme. Accordingly, the airtime had no value to creditors, despite its market value. On rehearing, the Fifth Circuit vacated its initial opinion and certified the controlling issue to the Texas Supreme  Court: “Considering the definition of ‘value’ in section 24.004(a) of the Texas Business and Commerce Code, the definition of ‘reasonably equivalent value’ in section 24.004(d) of the Texas Business and Commerce Code, and the comment in the Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Act stating that ‘value’ is measured ‘from a creditor’s viewpoint,’ what showing of ‘value’ under TUFTA is sufficient for a transferee to prove the elements of the affirmative defense under section 24.009(a) of the Texas Business and Commerce Code?” Janvey v. The Golf Channel, No. 13-11305 (June 30, 2015).

Court: “Considering the definition of ‘value’ in section 24.004(a) of the Texas Business and Commerce Code, the definition of ‘reasonably equivalent value’ in section 24.004(d) of the Texas Business and Commerce Code, and the comment in the Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Act stating that ‘value’ is measured ‘from a creditor’s viewpoint,’ what showing of ‘value’ under TUFTA is sufficient for a transferee to prove the elements of the affirmative defense under section 24.009(a) of the Texas Business and Commerce Code?” Janvey v. The Golf Channel, No. 13-11305 (June 30, 2015).

Category Archives: Bankruptcy

A revised Templeton v. O’Cheskey did not alter the Fifth Circuit’s analysis about proof of a Ponzi scheme, but slightly clarified the scope of its holding about “good faith” under the fraudulent transfer provision of the Bankruptcy Code. That holding was that the “good faith test under Section 548(c) is generally presented as a “two-step inquiry” into (1) whether the transferee had “inquiry notice” of the transferor’s possible insolvency or possible fraud and (2) if so, whether the transferee then satisfied a “diligent investigation” requirement. No. 14-10563 (June 8, 2015). (The Fifth Circuit addressed the related “good faith” requirement under TUFTA in GE Capital v. Worthington National Bank, 754 F.3d 297 (5th Cir. 2014)).

Adler, the distributing agent for a bankrupt business, sought to sue a law firm for allegedly mishandling its affairs and causing its financial problems. The business’s Third Amended Plan of Reorganization had a provision that retained its standing to pursue avoidance and fraudulent transfer actions against a list of named defendants (which did not include the law firm). The Plan also had a provision reserving “[a]ny and all other claims and causes of action which may have been asserted by the Debtor prior to the Effective Date.” The Fifth Circuit held that this was “exactly the sort of blanket reservation that is insufficient to preserve the debtor’s standing.” (citing Dynasty Oil & Gas LLC v. Citizens Bank, 540 F.3d 551 (5th Cir. 2008)). On waiver grounds, he Court declined to consider whether such a reservation would be sufficient if “(1) the defendant is a non-creditor [and thus not entitled to vote on the plan] and (2) the reorganization plan clearly identifies how the proceeds of the claim will be distributed.” Adler v. Frost, No. 14-31109 (June 11, 2015, unpublished).

As a counterpoint to the recent case of Alonso v. Abide — which required leave of court to sue a bankruptcy trustee for alleged negligence in handling a claim against a debtor’s insurer — in Carroll v. Abide, the Fifth Circuit reversed the dismissal of a claim against a trustee because leave was not required. No. 14-31230 (June 11, 2015). The debtors sued, alleging that the trustee violated their Fourth Amendment rights in seizing a computer. Again applying Barton v. Barbour, 104 U.S. 126 (1881), the Court concluded: “[B]ecause the [debtors] complain of the bankruptcy trustee’s conduct while carrying out district court orders, we conclude that the plaintiffs were not required to seek permission from the bankruptcy court before filing suit in the district court regarding the challenged conduct.” (emphasis added).

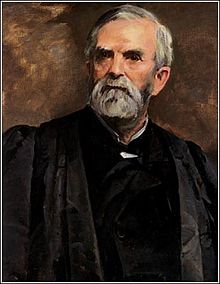

Former bankruptcy debtors sued their trustee, alleging that he failed to sue an insurer who could have satisfied many creditors’ claims. The district court dismissed because the plaintiffs did not first get leave from the bankruptcy court that appointed the trustee, and the Fifth Circuit affirmed under Barton v. Barbour, 104 U.S. 126, 128 (1881) (an opinion by the otherwise unmemorable William Burnham Woods, right).

Former bankruptcy debtors sued their trustee, alleging that he failed to sue an insurer who could have satisfied many creditors’ claims. The district court dismissed because the plaintiffs did not first get leave from the bankruptcy court that appointed the trustee, and the Fifth Circuit affirmed under Barton v. Barbour, 104 U.S. 126, 128 (1881) (an opinion by the otherwise unmemorable William Burnham Woods, right).

The debtors contended that Stern v. Marshall implicitly overruled Barton, in part, because the bankruptcy court would lack final adjudicative authority over their state law tort claims. The Fifth Circuit disagreed, holding that under Barton: “If a bankruptcy court concludes that the claim against a trustee is one that the court would not itself be able to resolve under Stern, that court can make the initial decision on the procedure to follow. Once a bankruptcy court makes such a determination, this court can review the utilized procedure.” Villegas v. Schmidt, No. 14-40423 (May 28, 2015).

In Harris v. Viegelahn, No. 14-400 (May 18, 2015), the Supreme Court resolved a split between the Third and Fifth Circuits and held 9-0 (contrary to the Fifth’s position) that “by excluding postpetition wages from the converted Chapter 7 estate (absent a bad-faith conversion), 11 U.S.C. § 348(f) removes those earnings from the pool of assets that may be liquidated and distributed to creditors.”

Among several issues addressed in the complicated bankruptcy appeal of Templeton v. O’Cheskey, the Fifth Circuit considered whether the “ordinary course of business” defense applied to alleged preferential transfers. The Court noted that a “true” Ponzi scheme is one with “operations build on the collection of funds from new investments to pay off prior investors.” Here, “only a portion of the funds controlled by [Debtor] ([Creditor] estimates 9%) was used to pay Ponzi-like returns to investors,” and the

Among several issues addressed in the complicated bankruptcy appeal of Templeton v. O’Cheskey, the Fifth Circuit considered whether the “ordinary course of business” defense applied to alleged preferential transfers. The Court noted that a “true” Ponzi scheme is one with “operations build on the collection of funds from new investments to pay off prior investors.” Here, “only a portion of the funds controlled by [Debtor] ([Creditor] estimates 9%) was used to pay Ponzi-like returns to investors,” and the  “record is clear that [Debtor] engaged in substantial legitimate business–owning or controlling approximately 14,000 housing units.” Therefore, the defense could apply, and these transfers were remanded for further consideration. No. 14-10563 (revised May 12, 2015).

“record is clear that [Debtor] engaged in substantial legitimate business–owning or controlling approximately 14,000 housing units.” Therefore, the defense could apply, and these transfers were remanded for further consideration. No. 14-10563 (revised May 12, 2015).

The Cantus filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, and after their case was converted to Chapter 7, sued their bankruptcy attorney for malpractice. That suit settled for roughly $300,000, leading to a dispute between the Cantus and the Chapter 7 Trustee as to who should receive the proceeds. The Fifth Circuit found that the estate suffered pre-conversion injury as a result of the alleged misconduct, including diversion of assets, time wasted with an unconfirmable Chapter 11 plan, and additional attorneys fees. Therefore, the causes of action against the attorney “accrued prior to conversion and belong to the estate.” Cantu v. Schmidt, No. 14-40597 (April 17, 2015).

A law firm sought $130,000 in fees for representing a bankruptcy debtor; the bankruptcy court awarded $20,000, noting the firm’s lack of success in delivering a measurable benefit to the estate. While a Fifth Circuit panel affirmed, citing the test in In re: Pro-Snax Distributors, Inc., 157 F.3d 414 (5th Cir. 1998), all three judges called for en banc reconsideration of that opinion. That request was granted unanimously in Barron & Newburger, P.C. v. Texas Skyline, Ltd., which recognized that the “retrospective, ‘material benefit’ standard enunciated in Pro–Snax conflicts with the language and legislative history of § 330, diverges from the decisions of other circuits, and has sown confusion in our circuit.” Accordingly, the full Court overturned Pro–Snax’s attorney’s-fee rule to “adopt the prospective, ‘reasonably likely to benefit the estate’ standard endorsed by our sister circuits.” While the division of some en banc votes can offer insight on subtle aspects of judges’ philosophies, this unanimous decision shows that sometimes, the full court will simply fix what it regards as an earlier mistake, if that mistake has sufficiently far-reaching consequences within the Circuit.

A law firm sought $130,000 in fees for representing a bankruptcy debtor; the bankruptcy court awarded $20,000, noting the firm’s lack of success in delivering a measurable benefit to the estate. While a Fifth Circuit panel affirmed, citing the test in In re: Pro-Snax Distributors, Inc., 157 F.3d 414 (5th Cir. 1998), all three judges called for en banc reconsideration of that opinion. That request was granted unanimously in Barron & Newburger, P.C. v. Texas Skyline, Ltd., which recognized that the “retrospective, ‘material benefit’ standard enunciated in Pro–Snax conflicts with the language and legislative history of § 330, diverges from the decisions of other circuits, and has sown confusion in our circuit.” Accordingly, the full Court overturned Pro–Snax’s attorney’s-fee rule to “adopt the prospective, ‘reasonably likely to benefit the estate’ standard endorsed by our sister circuits.” While the division of some en banc votes can offer insight on subtle aspects of judges’ philosophies, this unanimous decision shows that sometimes, the full court will simply fix what it regards as an earlier mistake, if that mistake has sufficiently far-reaching consequences within the Circuit.

In Wellness Wireless, Inc. v. Infopia America, LLC, the district court dismissed a suit on a note for lack of subject matter jurisdiction, noting the potential effect on the estate of a company in bankruptcy. The Fifth Circuit faulted this reasoning as “plainly wrong,” noting that Article III courts have jurisdiction over bankruptcy matters and simply refer them to bankruptcy courts as a matter of course. The Court also disagreed as to an alternative ground for dismissal, based on the debtor being a necessary party under Fed. R. Civ. P. 19, noting that the debtor had disclaimed any interest in the funds at issue during the bankruptcy case. No. 14-20024 (March 24, 2015, unpublished).

Satterwhite appealed an adverse ruling from the bankruptcy court, and then to the district court. In the district court, after judgment, he filed a motion for new trial, to modify the judgment, and for findings of fact and conclusions of law. After the trial court denied those motions, he filed a notice of appeal that would have been timely in an “ordinary” appeal under Fed. R. App. P. 4. Unfortunately, this bankruptcy appeal fell under Fed. R. App. P. 6, which only allows a motion for rehearing filed within 14 days of judgment to extend the appellate deadline. Satterwhite v. Guin, No. 14-20430 (March 31, 2015, unpublished).

Allen Stanford spent close to $6 million advertising his investment firm on the Golf Channel. After his empire collapsed, the receiver sued the Golf Channel under the Texas fraudulent transfer statute. The Channel successfully defended in the district court on the ground that it gave reasonably equivalent value. Janvey v. The Golf Channel, No. 13-11305 (March 11, 2015). Unfortunately for the Channel, because the receiver proved Stanford was running a Ponzi scheme, the question was whether it gave value from the perspective of the creditors, not whether it provided quality advertising from the perspective of Stanford’s business operation. “Golf Channel argues that its advertising services did not further the Stanford Ponzi scheme and that the $5.9 million reasonably represents the market value of those services. . . . TUFTA makes no distinction between different types of services or different types of transferees, but requires us to look at the value of any services from the creditors’ perspective. We have no authority to create an exception for ‘trade creditors.'” Accordingly, the Fifth Circuit reversed.

Allen Stanford spent close to $6 million advertising his investment firm on the Golf Channel. After his empire collapsed, the receiver sued the Golf Channel under the Texas fraudulent transfer statute. The Channel successfully defended in the district court on the ground that it gave reasonably equivalent value. Janvey v. The Golf Channel, No. 13-11305 (March 11, 2015). Unfortunately for the Channel, because the receiver proved Stanford was running a Ponzi scheme, the question was whether it gave value from the perspective of the creditors, not whether it provided quality advertising from the perspective of Stanford’s business operation. “Golf Channel argues that its advertising services did not further the Stanford Ponzi scheme and that the $5.9 million reasonably represents the market value of those services. . . . TUFTA makes no distinction between different types of services or different types of transferees, but requires us to look at the value of any services from the creditors’ perspective. We have no authority to create an exception for ‘trade creditors.'” Accordingly, the Fifth Circuit reversed.

This summer, in the panel opinion of Barron & Newburger, P.C. v. Texas Skyline, Ltd., No. 13-50075 (July 15, 2014), the Fifth Circuit affirmed the partial denial of a fee application based on its earlier opinion of In re: Pro-Snax Distributors, Inc., 157 F.3d 414 (5th Cir. 1998). That earlier opinion rejected a “reasonableness” test in the application of Bankruptcy Code § 330 — which would have asked “whether the services were objectively beneficial toward the completion of the case at the time they were performed” — in favor of a “hindsight” approach, asking whether the professionals’ work “resulted in an identifiable, tangible, and material benefit to the bankruptcy estate.” All three panel members joined a special concurrence asking the full Court to reconsider Pro-Snax en banc, and that invitation was recently accepted by a majority of active judges. Law360 provides some good additional commentary about the en banc vote.

EnCana Oil & Gas hired Seiber as a general contractor, who in turn hired Holt and TAUG as subcontractors. Seiber failed to make timely payments. EnCana interpleaded the funds at issue, and Seiber then filed for bankruptcy — before entry of a final order in the interpleader case. Holt Texas, Ltd. v. Zayler, No. 13-41153 (Nov. 3, 2014).

EnCana Oil & Gas hired Seiber as a general contractor, who in turn hired Holt and TAUG as subcontractors. Seiber failed to make timely payments. EnCana interpleaded the funds at issue, and Seiber then filed for bankruptcy — before entry of a final order in the interpleader case. Holt Texas, Ltd. v. Zayler, No. 13-41153 (Nov. 3, 2014).

Holt and TAUG alleged that they had materialmen’s liens under Texas law that removed the funds from Seiber’s bankruptcy estate; Seiber’s bankruptcy trustee argued that the filing of the interpleader action “automatically satisfied its liability to Seiber, thus transferring legal possession of the funds to Seiber and the bankruptcy estate.”

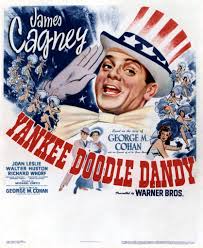

The Fifth Circuit disagreed with the trustee and reversed the bankruptcy court, reasoning: “If this were so, the interpleader would be the final judge of its own legal obligations relative to the dispute, by depositing a sum solely determined by it, washing its hands of any relationship to the dispute and walking away whistling Yankee Doodle.”

The meaning of the word “value,” a seemingly simple word, lies at the heart of most economic theory. In the Fifth Circuit, in the context of a defense under section 548(c) of the Bankruptcy Code to a fraudulent transfer claim, “value” is measured “from the perspective of the transferee: How much did the transferee ‘give’?” Williams v. FDIC, No. 12-20687 (Oct. 16, 2014) (discussing Jimmy Swaggart Ministries v. Hayes, 310 F.3d 796 (5th Cir. 2002)). (Although, as footnote 3 of Williams observes, the answer may be different under state law.)

In Williams, a debtor company paid $367,681.35 to a bank, on an obligation owed entirely by the individual who owed the debtor. The bankruptcy trustee proved these payments were a fraudulent transfer, but the bank won below by showing two items of value: (1) forbearance as to eviction, which had substantial value to the debtor’s business, and (2) roughly $250,000 in “reasonable rental rate” for the period when the debtor occupied the premises in question. The Fifth Circuit disregarded the first as irrelevant from the debtor’s perspective under Swaggart. As to the second, the Court required “netting” of the loan payments received by the bank, against the rent the bank could have received, and rendered judgment for the trustee for the difference. This holding turns on a detailed analysis of the term “value” in 548(c), as distinguished from “reasonably equivalent value” in a defense elsewhere in the Code.

On October 2, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in ASARCO v. Baker Botts, L.L.P., a Fifth Circuit case about enhancement of professional fees for a “rare and extraordinary” result in bankruptcy fraudulent transfer litigation.

Earlier this year, the Fifth Circuit ordered the remand to state court of litigation between Vantage Drilling and Hsin-Chi Su. Vantage Drilling Co. v. Su, 741 F.3d 535 (5th Cir. 2014). Meanwhile, several marine shipping companies, owned in whole or in part by Su, filed for Chapter 11 protection in the Southern District of Texas, and Vantage intervened in those proceedings. TMT Procurement Corp. v. Vantage Drilling Co., No. 13-20622 (Sept. 3, 2014). The district court entered several orders related to DIP financing and shares of Vantage stock, which Vantage appealed.

The Fifth Circuit rejected a mootness challenge, concluding that the DIP lender’s awareness of Vantage’s claim removed the appeal from certain Code provisions that limit appellate rights. The Court then held that (1) the shares at issue were not estate property — even though the district court’s orders had tied them to the business affairs of the debtor, and (2) the ongoing state court litigation was not “related to” the estate because it was an action “between non-debtors over non-estate property.” Accordingly, the lower courts lacked jurisdiction to enter the orders challenged by Vantage, and the Fifth Circuit vacated them.

In Flooring Systems, Inc. v. Chow, these events led to a dispute about whether a preferential transfer occurred:

- June 2007: Flooring Systems, Inc. obtains a Texas state court judgment against Eric Poston.

- October 26, 2007: State court appoints a receiver to collect assets to satisfy the judgment.

- November 20, 2007: Flooring Systems serves Plain Capital Bank with a certified copy of the receivership order.

- December 18, 2007: Bank turns over $22,923.05 check.

- January 15, 2008: Receiver pays Flooring Systems $18,529.64

- January 31, 2008. Poston files for bankruptcy, Chow appointed as trustee.

If the transfer was made on October 26, it did not implicate the 90-day preferential transfer period in the Bankruptcy Code; if made on the 20th, it did. Citing a Texas statute that provides: “[T]he rights of a receiver . . . do not attach until the financial institution receives service of a certified copy of the order of receivership . . . ,” the Fifth Circuit held that the transfer did not occur until the date of service on the bank, and affirmed. No. 13-41050 (Aug. 28, 2014).

In Galaz v. Galaz, a bankruptcy debtor sued her ex-husband for the fraudulent transfer of a royalty interest in the works of the Ohio Players, a popular funk band in the 1970s. Nos. 13-50781, 50783 (Aug. 25, 2014). Her ex-husband brought third-party claims against a music producer, who in turn brought counterclaims. The resulting litigation produced judgments in favor of both the debtor and the producer against the ex-husband. On appeal, in a landscape formed by the legacy of Stern v. Marshall, 131 S. Ct. 2594 (2011), the Fifth Circuit held:

1. While the debtor’s fraudulent transfer claim was not the “paradigmatic” case where assets are transferred out of the estate, it could still “conceivably” affect the estate, and the bankruptcy court thus had statutory jurisdiction because these non-core claims related to her bankruptcy;

2. The producer’s counterclaims, however, had no connection to the estate and the bankruptcy court had no statutory jurisdiction over them;

3. Under Stern, in light of the present posture of cases from this Circuit and one awaiting Supreme Court review, the implied consent of the parties cannot confer constitutional jurisdiction on the bankruptcy court to enter final judgment such as the debtor’s claim here.

Accordingly, the Court reversed and remanded, hinting that the bankruptcy court could prepare proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law for the district court as to the debtor’s claims. The Court also noted that the debtor had standing as a creditor under the Texas Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Act even though her personal interest in the royalties flowed through a business she partly owned.

A bankruptcy court entered judgment against Defendants, who the filed a new federal lawsuit for a declaratory judgment that the bankruptcy court lacked jurisdiction. Jacuzzi v. Pimienta, No. 13-41111 (August 5, 2014). The district court found that it lacked jurisdiction over that suit, and the Fifth Circuit reversed. Noting that as a general matter, it is procedurally proper to attack a judgment for lack of jurisdiction in a collateral proceeding, the Court found that the lawsuit raised federal questions about due process rights and compliance with the federal rules for service of process. Accordingly, there was federal jurisdiction to hear the challenge to the bankruptcy court judgment.

The trustee of a litigation trust formed from the bankruptcy of Idearc, Inc. sued its former parent, Verizon, alleging billions of dollars in damages in connection with its spinoff. After a bench trial and several other orders, the district court ruled in favor of defendants, and the Fifth Circuit affirmed in U.S. Bank, N.A. v. Verizon Communications, No. 13-10752 (revised Sept. 2, 2014).

The opinion, while lengthy, still only hints at the complexity of the case, and much of its analysis is fact-specific. Some of the issues addressed include:

1. A bankruptcy litigation trust does not have a right to jury trial on a fraudulent transfer claim, when the defendant creditor has filed a proof of claim in the bankruptcy, and the bankruptcy court must resolve whether a fraudulent transfer occurred to rule on that claim (analyzing and applying Langemkamp v. Culp, 498 U.S. 42 (1990), in light of Stern v. Marshall, 131 S. Ct. 2594 (2011)).

2. In the context of determining whether the district court reviewed an earlier ruling correctly, on pages 26-27, the Court provided crisp definitions of the basic concepts of dictum and holding.

3. In the course of rejecting an argument about the refusal to admit several pieces of evidence, the Court noted that the trustee “does not discuss how each specific piece of evidence was likely to affect the outcome of the trial, in light of all the evidence presented.”

4. A defense expert, without experience in the particular industry, was still qualified to speak to valuation methodology in the bench trial, and “we cannot reverse the district court for adopting one permissible view over the other.”

5. The Court thoroughly reviewed the fiduciary duties owed from a parent to a subsidiary under Delaware law, while affirming the district court’s conclusions about causation associated with their alleged breach.

A large group of Dallas firefighters and police officers, involved in class action litigation against the City, filed a declaratory judgment action in the bankruptcy case of a law firm that had once represented them. They sought a declaration that neither the firm, nor the bankruptcy trustee, continued to represent them in their litigation or was entitled to any fee in that litigation. Caton v. Payne, No. 13-41182 (July 16, 2014, unpublished). After reminding in a lengthy footnote one that the final judgment rule for bankruptcy appeals is viewed “in a practical, less technical light,” the Fifth Circuit nevertheless agreed that the appeal from the ruling on that declaration was not ripe: “It is undisputed that the Class Action Lawsuits remain pending, that no recovery has been made, and that there may never be a recovery, which would preclude any contingent fee award as to which [bankrupt firm] (through the Trustee) may or may not be entitled to a share. Moreover, the Trustee has not yet demanded a fee, or threatened legal action to recover a fee.”

A law firm appealed the partial denial of its bankruptcy fee application. The bankrupty court said “its ruling was informed by the bad conduct of the Debtors themselves, which should have lead [the firm] to withdraw from the case sooner than it ultimately did.” The district court said the record showed that “this bankruptcy proceeding was doomed at the outset, and arguably could not have been filed in good faith under Chapter 11.” Barron & Newburger, P.C. v. Texas Skyline, Ltd., No. 13-50075 (July 15, 2014). The Fifth Circuit affirmed, noting that its earlier opinion of In re: Pro-Snax Distributors, Inc., 157 F.3d 414 (5th Cir. 1998) rejected a “reasonableness” test in the application of Bankruptcy Code § 330 — which would have asked “whether the services were objectively beneficial toward the completion of the case at the time they were performed” — in favor of a “hindsight” approach, asking whether the professionals’ work “resulted in an identifiable, tangible, and material benefit to the bankruptcy estate.” That said, all three panel members joined a special concurrence asking the full Court to reconsider Pro-Snax en banc, observing that its outright rejection of forward-looking reasonableness “appears to conflict with the language and legislative history of § 330, diverges from the decisions of other circuits, and has sown confusion in our circuit.”

1. Creditors get the money. Debtor filed for Chapter 13 personal bankruptcy. He made payments to the Trustee for some time. He then converted to Chapter 7, leaving the Trustee holding money paid under the Chapter 13 plan. “[W]ages paid to the trustee pursuant to the Chapter 13 plan should be distinguished from the debtor’s other property acquired after the date of filing.” Viegelahn v. Harris, No. 13-50374 (July 7, 2014)

2. Creditors get the money. The stay lifted. Secured Creditor foreclosed. Under federal law, its attorneys fees were subject to the customary review under the Bankruptcy Code. Under state law, its attorneys fees were fixed by contract. Held: federal law controls, and the case was remanded for review under federal standards. In re 804 Congress LLC, No. 12-50382 (June 23, 2014)

Placid Oil filed for bankruptcy and the claim bar date, published in the Wall Street Journal, passed in 1987. “By the early 1980s, Placid was aware, generally, of the hazards of asbestos exposure and, specifically, of Mr. Williams’s exposure in the course of

his employment. Prior to the Plan’s confirmation, no asbestos-related claims

had ever been filed against Placid, and the Williamses did not file any proof of

claim.” Williams v. Placid Oil Co., No. 12-11120 (May 27, 2014). Applying In re: Crystal Oil, 158 F.3d 291 (5th Cir. 1998), the Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment in the Williamses subsequent tort suit against Placid: “Although Placid knew of the dangers of asbestos and Mr. Williams’s exposure, such information suggesting only a risk to the Williamses does not make the Williamses known creditors. Here, Placid had no specific knowledge of any actual injury to the Williamses prior to its bankruptcy plan’s confirmation.” (Donald Rumsfeld’s 2002 discussion of the broader philosophical point is reviewed here.)

In United States ex rel Spicer v. Navistar Defense, LLC, the Fifth Circuit found that bankruptcy debtors failed to make adequate disclosure of a potential False Claims Act claim as an estate asset. No. 12-10858 (May 5, 2014). Accordingly, the trustee was the real party in interest and was able to take over the administration of the claim, even though he did not learn of it until after the bankruptcy closed and long after suit was filed on the claim. The review of the debtors’ disclosure is of broad general interest. As to the merits, the Court affirmed dismissal, reminding that “a false certification of compliance, without more, does not give rise to a false claim for payment unless payment is conditioned on compliance.”

At issue in Asarco v. Baker Botts. L.L.P. was a fee enhancement associated with an exceptional recovery in fraudulent transfer litigation for a bankruptcy estate. No. 12-40997 (April 30, 2014). The Fifth Circuit credited the bankruptcy court’s detailed findings about the quality of the law firms’ work and the “rare and extraordinary” result. In so doing, the Court reminded that “[b]ecause this court, like the Supreme Court, has not held that reasonable attorneys’ fees in federal court have been ‘nationalized,’ the bankruptcy court’s charts comparing general hourly rates of out-of-state firms and rates charged in cases pending in other circuits are not relevant.” The Court rejected the firms’ request for compensation from the estate for defending their fee applications, reasoning that the Code had sufficient protections against vexatious litigation, and declining to further expand the American Rule about defendants’ fees.

A law firm appealed the disposition of its fee application. The district court affirmed the bankruptcy court in part, vacated in part, and remanded for the firm to make another fee request that provided more necessary information. Okin Adams & Kilmer v. Hill, No. 13-20035 (March 24, 2014). The firm appealed to the Fifth Circuit, which concluded it had no appellate jurisdiction because the order was not final: “Given that the bankruptcy court must perform additional fact-finding and exercise discretion when determining an appropriate attorney’s fee award, the district court’s order requires the bankruptcy court to perform judicial functions upon remand.” A detailed dissent concluded that, while the district court’s order required “more than a mechanical entry of judgment,” “it also involves only mechanical and computational tasks that are ‘unlikely to affect the issue that the disappointed party wants to raise on appeal.'” Accordingly, it warned that “refusing to hear this appeal undermines the long-recognized, salutary purpose of allowing appeals in discrete issues well before a final order in bankruptcy.”

When a homestead is permanently exempted from a bankruptcy estate, are any proceeds from a subsequent sale of the homestead also permanently exempt? Viegelahn v. Frost found they were not. No. 12-50811 (March 5, 2014). Frost argued that In re Zibman, 268 F.3d 298 (5th Cir. 2001), was distinguishable because he sold his homestead after petitioning for bankruptcy, when the homestead was already exempted, while Zimban concerned homestead proceeds obtained before bankruptcy. The Fifth Circuit found that distinction immaterial, concluding that once a debtor sells his homestead the essential character of the homestead changes from “homestead” to “proceeds,” placing it under a more limited six month exemption. Accordingly, when a debtor does not reinvest the proceeds within that period, they are removed from the protection of Texas law and are no longer exempt from the estate.

In Credit Union Liqudity Services, LLC v. Green Hills Devel. Co. LLC, the Fifth Circuit found that a creditor lacked standing under section 303(b) of the Bankruptcy Code to file an involuntary bankruptcy proceeding, because the creditor’s debt was subject to a ‘bona fide dispute.’ No. 12-60784 (Feb. 3, 2014). The Court first held that the debtor had not waived arguments about 303(b) by failing to file a conditional cross-appeal from the district court’s dismissal order, finding that the arguments fell under the rule allowing affirmance on any argument supported by the record. In reaching its conclusion, the Court noted that the claim had been subject to “unresolved, multiyear litigation.” The Court also observed that 2005 amendments to the Code defined a bona fide dispute as one “to liability or amount,” a change which drew into question earlier authority that focused only on liability. That change can allow consideration of counterclaims related to the creditor’s claim.

Federal Rule of Bankruptcy Procedure 8002(a) says that the notice of appeal from bankruptcy to district court must be filed within 14 days of the judgment or order at issue. Here, Smith filed his notice of appeal to district court thirty days after entry of final judgment. Smith v. Gartley, No. 13-50154 (Dec. 16, 2013). After reviewing the continuing validity of its older precedent of In re Stangel, 219 F.3d 498 (5th Cir. 2000), which held that this deadline is jurisdictional, the Fifth Circuit looked to In re Latture, 605 F.3d 830 (10th Cir. 2010), which reached the same conclusion. Because “the statute defining jurisdiction over bankruptcy appeals, 28 U.S.C. § 158, expressly requires that the notice of appeal be filed under the time limit provided in Rule 8002,” the time limit is jurisdictional.

In Croft v. Lowry, the debtor filed for bankruptcy after judgment was entered against him for attorneys fees and sanctions in two lawsuits. No. 13-50020 (Dec. 10, 2013). The debtor sought to lift the stay to pursue appeals of those judgments; the adverse parties in the lawsuits opposed, arguing that the debtor’s defensive appellate rights were estate property and could be sold. The district court ruled for the debtor and the Fifth Circuit reversed. Noting that only two courts have addressed this issue, and reached different results, the Court concluded that the rights had quantifiable value and were thus “property” under Texas law. The Court noted that the rights had value to the estate, since appellate success would reduce liability, as well as the judgment creditors, who may be willing to pay some amount to avoid litigation expense and reversal risk. “Whether the defensive appellate rights are sold depends upon whether the parties can agree on the value of those rights, not whether they have any value at all.” (emphasis in original)

Plaintiffs sued Blackburn for breach of contract with respect to three promissory notes and for fraud in a stock transaction. Highground, Inc. v. Blackburn, No. 13-30248 (Sept. 25, 2013, unpublished). Plaintiffs recovered on the notes but not the fraud claim, and the bankruptcy court awarded $25,000 as a “fair fee” for that result. Plaintiffs appealed, seeking fees for the fraud claim as well, arguing that their litigation was “inextricably intertwined” with the note claims. Applying Tony Gullo Motors I, L.P. v. Chapa, 212 S.W.3d 299 (Tex. 2006), the Fifth Circuit agreed with the lower court: “Appellants prevailed on the notes claim because Blackburn signed the notes without authority to do so, not because of the allegations of fraud relating to other aspects of the purchase agreement . . . .” The case presents a clean example of claims against the same party that are nevertheless not “inextricably intertwined” for purposes of an attorneys fee award. (For thorough review of this principle, and other key points about fee awards, please consult the book “How to Recover Attorneys Fees in Texas” by my colleagues Trey Cox and Jason Dennis.)

The plaintiff in a personal injury case was found to be judicially estopped from asserting the claim because it was not properly disclosed in her personal bankruptcy, even though it arose post-petition. Flugence v. Axis Surplus Ins. Co., No. 13-30073 (Oct. 4, 2013). The trustee, however, could pursue the claim and its counsel could recover professional fees. Accordingly, the Court declined to declare that the trustee’s recovery was capped at the amount owing to creditors. (applying Reed v. City of Arlington, 650 F.3d 571 (5th Cir. 2011) (en banc)).

Devon Enterprises was not re-approved as a charter bus operator for the Arlington schools after the 2010 bid process. Devon Enterprises v. Arlington ISD, No. 13-10028 (Oct. 8, 2013, unpublished). Devon argued that it was rejected solely because of its bankruptcy filing in violation of federal law; in response, the district cited safety issues and insurance problems. An email by the superintendent said “[Alliance] was the company that [AISD] did not award a bid to for charter bus services because they are currently in bankruptcy.” Calling this email “some, albeit weak, evidence” that the filing was the sole reason for the decision, the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment for the school district.

Attorneys filed fee applications in a bankruptcy and the debtor responded with tort counterclaims. Frazin v. Haynes and Boone, No. 11-10403 (Oct. 1, 2013). The bankruptcy court entered judgment for the attorneys. The Fifth Circuit found a lack of jurisdiction over the DTPA counterclaim and remanded. It reasoned that Stern v. Marshall, 131 S. Ct. 2594 (2011), had overruled prior circuit precedent saying that bankruptcy courts could enter final judgments in all “core” proceedings. Applying Stern to these claims, the Court reasoned (1) the malpractice claim was intertwined with the fee application, (2) the fiduciary duty action was as well, as it sought fee forfeiture, but (3) “it was not necessary to decide the DTPA claim to rule on the Attorneys’ fee applications” (including whether the claim was an impermissible “fracturing” of a professional negligence claim under Texas law) The court noted that the district court may have jurisdiction to enter final judgment on the claim. A dissent would not remand “because no harm is done, at least in this case, and the district court will no doubt simply dismiss whatever has been remanded.”

An unsecured creditor contended that the gross negligence of a bankruptcy trustee allowed a key asset to escape the estate. The court agreed and ordered payment from Liberty Mutual’s bond for the trustee. The Fifth Circuit affirmed, finding: (1) the relevant limitations period was set by a 4-year federal statute rather than a 2-year state one, (2) the finding of gross negligence was not clearly erroneous, and (3) expert testimony was not necessary to establish gross negligence in this situation: “While the precise course of action the Trustee should have taken may be subject to reasonable debate, it requires no technical or expert knowledge to recognize that she affirmatively should have undertaken some form of action to acquire for the bankruptcy estate the assets to which it was entitled.” Liberty Mutual v. United States, No. 12-10677 (revised August 20, 2013).

Acceptance Loan had a lien on a Mississippi office building, which was the principal asset of S. White Transportation (“SWT”) when it went into bankruptcy. Acceptance Loan Co. v. S. White Transportation, No. 12-60648 (August 5, 2013). Acceptance received notice of SWT’s bankruptcy several times. After plan confirmation, Acceptance sought a declaration that its lien survived. The Fifth Circuit held that “passive receipt of notice” did not constitute “participation” in the bankruptcy under In re Ahern Enterprises, 507 F.3d 817, 822 (5th Cir. 2007). Therefore, the general rule applied that “a secured creditor with a loan secured by a lien on the assets of the debtor who becomes bankrupt before the loan is repaid may ignore the bankruptcy proceeding and look to the lien for satisfaction of the debt.”

“Equitable mootness” is a prudential doctrine that balances a litigant’s interest in appellate review against the need for finality of a bankruptcy plan. It has three elements: (i) whether a stay has been obtained, (ii) whether the plan has been ‘substantially consummated,’ and (iii) whether the relief requested would affect either the rights of parties not before the court or the success of the plan.” Official Committee of Unsecured Creditors v. Moeller, Nos. 12-50718, 50805 (July 24, 2013). The Fifth Circuit declined to apply the doctrine in this case, finding that Chase had at best shown only “speculative” harm to other parties. Dicta in the opinion expresses skepticism that the doctrine can apply to an adversary proceeding.

Creditors sought to assert state law tort claims that had at one point belonged to a bankruptcy estate. Wooley v. Haynes & Boone LLP No. 11-51106 (Apr. 18, 2013). The Fifth Circuit found that the reservation language in the reorganization plan was too vague to satisfy the requirements of the Code as to these claims: “Neither the Plan nor the disclosure statement references specific state law claims for fraud, breach of fiduciary duty, or any other particular cause of action. Instead, the Plan simply refers to all causes of action, known or unknown. As noted, such a blanket reservation is not sufficient to put creditors on notice.” The opinion reviews the handful of Fifth Circuit opinions that establish the guidelines on this basic topic in bankruptcy litigation, and contrasts with another recent opinion that found a set of avoidance claims had been properly reserved.

Smyth, a partner in a bankrupt entity, complained that the bankruptcy court had no jurisdiction to authorize the sale of claims he sought to assert individually. Smyth did not obtain a stay of the sale order, however, rendering the appeal moot: “When an appeal is moot because an appellant has failed to obtain a stay, this court cannot reach the question of whether the bankruptcy court had jurisdiction to sell the claims.” Smyth v. Simeon Land Development LLC (April 18, 2013, unpublished).

Contractors who worked on a bankrupt hospital project disputed their relative lien priorities. First National Bank v. Crescent Electrical Supply, No. 12-10386 (April 5, 2013). The threshold question under Texas law was when work was “visible from inspection,” and was not “preliminary or preparatory.” (citing Tex. Prop. Code §§ 53.123 and 53.124 and Diversified Mortgage Investors v. Lloyd D. Blaylock General Contractor, 576 S.W.2d 794 (Tex. 1978)). In affirming the district court’s reversal of the bankruptcy court, the Fifth Circuit credited a stipulation by a party that was signed by counsel of record for another company, noting this was a “unique circumstance[],” where “the parties’ interests were significantly aligned and [the] party did not have record counsel of its own . . . .” The Court also found that the force of the stipulation overcome later testimony by the party’s president, when he admitted that the company had not yet obtained a permit at the time of its earliest work.

Teta v. Chow involved a WARN Act claim asserted by a putative class in bankruptcy court. No. 12-40271 (March 29, 2013, revised April 19, 2013). The Fifth Circuit began its review by comparing the rules for adversary proceedings, which automatically adopt Fed. R. Civ. P. 23, with those for a class proof of claim, which would not automatically implicate that rule. Applying Rule 23, the Court agreed that factors unique to the bankruptcy process can be considered in certification of a class by a bankruptcy court, but remanded for additional explanation by the district court on the issues of numerosity and superiority. A dissent would simply reverse the denial of class certification.

The secured lender held a $39 million claim in the bankruptcy of a hotel development; a reorganization plan was approved over its objection in a “cram-down” that called for repayment of the debt over ten years at 5.5 percent interest (1.75 percent above prime on the date of confirmation). Wells Fargo v. Texas Grand Prairie Hotel Realty LLC (No. 11-11109, March 1, 2013). The parties agreed that this “prime-plus” approach was appropriate under the plurality in Till v. SCS Credit Corp., 541 U.S. 465 (2004), but disputed the proper rate. The Court rejected a threshold challenge based upon “equitable mootness” because it reasoned that the appeal could be resolved with “fractional relief” rather than rejection of the plan. On the merits, the Court reaffirmed that it would review the choice of a cramdown rate for clear error rather than de novo, citing In re: T-H New Orleans Limited Partnership, 116 F.3d 790 (5th Cir. 1997)). After a thorough review of Till and subsequent cases, the court found no clear error in this prime-plus rate in this factual context.

A creditor successfully made a “credit bid” under the Bankruptcy Code for assets of a failed golf resort. Litigation followed between the creditor and guarantors of the debt, ending with a terse summary judgment order for the guarantors: “This is not rocket science. The Senior Loan has been PAID!!!!” Fire Eagle LLC v. Bischoff, No. 11-51057 (Feb. 28, 2013). The Fifth Circuit affirmed in all respects, holding: (1) the bankruptcy court had jurisdiction over the dispute with the guarantors because it had a “conceivable effect” on the estate; (2) the issue of the effect of the credit bid was within core jurisdiction and did not raise a Stern v. Marshall issue; (3) core jurisdiction trumped a forum selection clause on the facts of this case; (4) a transfer into the bankruptcy court based on the first-to-file rule was proper; and (5) the creditor’s bid extinguished the debt. On the last holding, the Court noted that the section of the Code allowing the credit bid did not provide for fair-market valuation of the assets, unlike other Code provisions.

The Bankruptcy Code requires that a plan receive a favorable vote from “at least one class of claims that is impaired under the plan.” 11 U.S.C. § 1129(a)(10). In Western Real Estate Equities LLC v. Village at Camp Bowie I, LP, thirty-eight unsecured trade creditors of a real estate venture voted to approve the debtor’s plan, while the secured creditor voted against it. No. 12-10271 (Feb. 26, 2013). The secured creditor complained that the consent was not valid because the plan “artificially” impaired the unsecured claims, paying them over a three-month period when the debtor had enough cash to pay them in full upon confirmation. Recognizing a circuit split, the Fifth Circuit held that section 1129 “does not distinguish between discretionary and economically driven impairment.” The Court conceded that the Code imposes an overall “good faith” requirement on the proponent of a plan, but held that the secured creditor’s argument here went too far by “shoehorning a motive inquiry and materiality requirement” into the statute without support in its text.

Earlier this year, the Fifth Circuit affirmed a fee enhancement in the Pilgrim’s Pride bankruptcy pursuant to section 330 of the Code. In ASARCO LLC v. Barclays Capital, the Court reversed an enhancement under section 328. No. 11-41010 (Dec. 11, 2012). “Section 328 applies when the bankruptcy court approves a particular rate . . . at the outset of the engagement, and § 330 applies when the court does not do so.” Id. at 13. A “necessary prerequisite” to section 328 enhancement is that the professional’s work was “not capable of anticipation.” Here, the Court found that the length of the ASARCO bankruptcy and the exodus of its employees after filing led to “commendable” work by Barclays that was still “capable of being anticipated.” See id. at 19 (analogizing Barclays to a car buyer who finds a new Corvette “needed far more than a car wash”).

The Fifth Circuit makes a major contribution to the law of international insolvency proceedings in Ad Hoc Group of Vitro Noteholders v. Vitro SAB de CV, Nos. 12-10542, 12-10869, 12-10750 (Nov. 28, 2012, rev’d Jan. 7, 2013). The opinion affirms a series of rulings under Chapter 15 of the Bankruptcy Code (which implements the UNCITRAL model law on cross-border insolvency): that (1) recognized the legitimacy of the Mexican reorganization proceeding involving Vitro (the largest glassmaker in Mexico with over $1 billion in debt), (2) recognized the validity of the foreign representatives appointed as a result of that proceeding, analogizing their appointment process to the management of a debtor in possession in the U.S., and (3) denied to enforce the plan on the grounds of comity. The detailed comity analysis turns on the U.S. bankruptcy system’s disfavor for non-consensual, non-debtor releases. The framework of the opinion is broadly applicable to a wide range of cross-border insolvency situations and addresses issues of first impression about the scope of relief available under Chapter 15. A representative article about the case in Businessweek appears here.