“Grafting ‘manifest disregard of the law’ as a basis for a losing party at arbitration to prevail under § 10(a)(4) would risk tension with Hall Street—and would run headlong into Oxford Health—by forcing us to conduct a less deferential review of a panel’s award than the FAA contemplates. Indeed, adopting [Appellant’s] reading essentially would rewrite the question a judge must ask from ‘whether the arbitrators construed the contract at all’ to ‘whether they construed it correctly.'” No. 24-10833 (Apr. 28, 2025).

“Grafting ‘manifest disregard of the law’ as a basis for a losing party at arbitration to prevail under § 10(a)(4) would risk tension with Hall Street—and would run headlong into Oxford Health—by forcing us to conduct a less deferential review of a panel’s award than the FAA contemplates. Indeed, adopting [Appellant’s] reading essentially would rewrite the question a judge must ask from ‘whether the arbitrators construed the contract at all’ to ‘whether they construed it correctly.'” No. 24-10833 (Apr. 28, 2025).

Category Archives: Arbitration

In Baker Hughes Saudi Arabia Co. Ltd. v. Dynamic Indus., Inc., the Fifth Circuit addressed the issue of arbitrability under a subcontract for an oil-and-gas project in Saudi Arabia. It reversed the district court’s decision that denied a motion to compel arbitration, holding that the dissolution of the “DIFC-LCIA” (the arbitral authority specified in the agremeent) did not make the arbitration agreement unenforceable.

In Baker Hughes Saudi Arabia Co. Ltd. v. Dynamic Indus., Inc., the Fifth Circuit addressed the issue of arbitrability under a subcontract for an oil-and-gas project in Saudi Arabia. It reversed the district court’s decision that denied a motion to compel arbitration, holding that the dissolution of the “DIFC-LCIA” (the arbitral authority specified in the agremeent) did not make the arbitration agreement unenforceable.

The Court emphasized that the parties’ dominant purpose was to arbitrate disputes generally, rather than to arbitrate exclusively before the DIFC-LCIA, so “the forum-selection clause (if it is one) is not integral to the subcontract ….” The Court further clarified that even if the DIFC-LCIA was unavailable as a forum, the district court should have considered whether the DIFC-LCIA rules could be applied by another available forum. No. 23-30827 (Jan. 27, 2025).

In RSM Prod. Corp. v. Gaz du Cameroun, S.A., the Fifth Circuit reversed the district court’s decision to vacate a revised arbitral award that reduced the damages awarded from $10.5 million to $6.5 million. The Court held that the arbitral tribunal had the authority to correct “computational errors” in its initial award and to determine what constituted such errors under the International Chamber of Commerce Rules, which the parties’ agreements incorporated. Applying the highly deferential standard of review for such issues, the Court held that the tribunal “arguably construed the parties’ contracts” when it issued the corrected award, even if it made a mistake in its interpretation.

In RSM Prod. Corp. v. Gaz du Cameroun, S.A., the Fifth Circuit reversed the district court’s decision to vacate a revised arbitral award that reduced the damages awarded from $10.5 million to $6.5 million. The Court held that the arbitral tribunal had the authority to correct “computational errors” in its initial award and to determine what constituted such errors under the International Chamber of Commerce Rules, which the parties’ agreements incorporated. Applying the highly deferential standard of review for such issues, the Court held that the tribunal “arguably construed the parties’ contracts” when it issued the corrected award, even if it made a mistake in its interpretation.

The Court rejected RSM’s argument that the tribunal exceeded its powers by reconsidering the merits of RSM’s claims. Distinguishing RSM’s authority, the Court noted that the ICC rules allowed this tribunal to correct any “clerical, computational or typographical error, or any errors of similar nature contained in [the] award.” The Court emphasized that “[t]he potential for … mistakes is the price of agreeing to arbitration” and that “[t]he arbitrator’s construction holds, however good, bad, or ugly.” No. 23-20583, Sept. 19, 2024.

Cure & Assocs., P.C. v. LP Fin., LLC addreses whether nonsignatories to an arbitration agreement can be compelled to arbitrate under state-law equitable estoppel principles. The Fifth Circuit held that these nonsignatories could be compelled, because they received direct benefits from the contractual relationship between the two signatories. Specifically, the Court noted that one of the nonsignatories was formed specifically to facilitate one signatory’s business with the other, sharing clients, employees, and office space. Under both California and Texas law, a nonsignatory can be compelled to arbitrate if it “deliberately seeks and obtains substantial benefits from the contract” with an arbitration clause. No. 23-40519, Oct. 1, 2024.

Cure & Assocs., P.C. v. LP Fin., LLC addreses whether nonsignatories to an arbitration agreement can be compelled to arbitrate under state-law equitable estoppel principles. The Fifth Circuit held that these nonsignatories could be compelled, because they received direct benefits from the contractual relationship between the two signatories. Specifically, the Court noted that one of the nonsignatories was formed specifically to facilitate one signatory’s business with the other, sharing clients, employees, and office space. Under both California and Texas law, a nonsignatory can be compelled to arbitrate if it “deliberately seeks and obtains substantial benefits from the contract” with an arbitration clause. No. 23-40519, Oct. 1, 2024.

Applying the international convention about arbitration, the Fifth Circuit found an abuse of discretion in not compelling arbitration because of equitable estoppel, reasoning:

While Bufkin was certainly free to name and then dismiss the foreign insurers, the district court was not free to disregard them in considering the domestic insurers’ motion to compel arbitration. Yet in focusing on Bufkin’s dismissal of the foreign insurers, the district court neglected to consider the foreign insurers’ part in the seamless coverage agreement struck by the parties, and Bufkin’s interactions with the insurers. Honing in, that coverage arrangement included the arbitration clause that afforded the insurers–foreign and domestic—“predictability in resolving disputes dealing with the substantial risks presented by a surplus lines insurance policy.” … The upshot is that indulging Bufkin’s pleading-and-then-dismissing gamesmanship by denying arbitration turns on its head the axiom that “[t]he linchpin for equitable estoppel is equity—fairness.”

Bufkin Enterprises, LLC v. Indian Harbor Ins. Co., No. 23-30171 (March 4, 2024) (emphasis added).

Michael Cloud, a former NFL running back, sued the NFL’s retirement fund for additional disability benefits. The Fifth Circuit reversed a trial-court ruling in his favor, noting the one-sided nature of the plan’s operations, but concluding:

Michael Cloud, a former NFL running back, sued the NFL’s retirement fund for additional disability benefits. The Fifth Circuit reversed a trial-court ruling in his favor, noting the one-sided nature of the plan’s operations, but concluding:

Cloud’s claim fails because he did not and cannot show any changed circumstances entitling him to reclassification to the highest tier of benefits. He could have appealed the 2014 denial of reclassification to Active Football status—but he did not do so. Instead, Cloud filed another claim for reclassification in 2016, which subjected him to a changed-circumstances requirement that he cannot meet—and did not try to meet. He therefore forfeited the issue at the administrative level and at any rate has not pointed to any clear and convincing evidence supporting his claim.

The district court’s findings about the NFL Plan’s disregard of players’ rights under ERISA and the Plan are disturbing. Again, this is a Plan jointly managed by the league and the players’ union. And we commend the trial court judge for her diligent work chronicling a lopsided system aggressively stacked against disabled players. But we also must enforce the Plan’s terms in accordance with the law.

Cloud v. Bell-Rozelle NFL Player Retirement Plan, No. 22-10710 (revised March 17, 2024).

An explosion on the M/V FLAMINIA (right) led to a $200 million arbitration award, which in turn led to an action to confirm that award in New Orleans federal court. The Fifth Circuit reversed for a lack of personal jurisdiction, concluding:

An explosion on the M/V FLAMINIA (right) led to a $200 million arbitration award, which in turn led to an action to confirm that award in New Orleans federal court. The Fifth Circuit reversed for a lack of personal jurisdiction, concluding:

- Forum. “When assessing personal jurisdiction in a confirmation action under the New York Convention, a Convention, a federal court should consider contacts related to the parties’ underlying dispute and not only contacts related to the arbitration proceeding itself. That holding aligns our court with every other circuit to address this issue.”

- Waiver. Unlike the facts of an earlier case involving a “letter of understanding,” the defendant’s LOU in tihs case said that it was “given without prejudice to any and all rights or defenses MSC, its agents or affiliates have or may have in the Proceedings.”

- Contacts. “[T]he dispute’s sole contact with the forum—the DVB’s shipping from the Port of New Orleans—did not occur as a result of MSC’s ‘own choice.’ … [The fact that the DVB was loaded onto the FLAMINIA in New Orleans was the result of “the unilateral activity” of other parties, not MSC.” (citations omitted).

No. 22-30808 (Jan. 29, 2024).

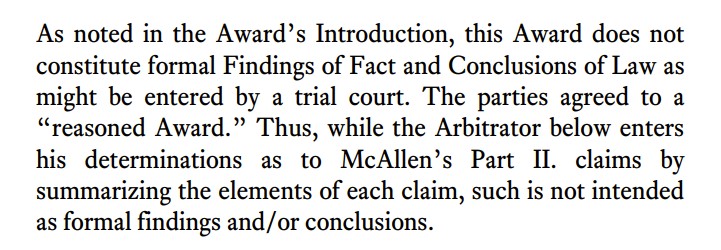

The arbitration award in Amberson v. McAllen said:

along with some additional explanation of the difference between a “reasoned award” and “Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law.” The Fifth Circuit rejected the argument that the arbitrator’s drawing of this distinction kept the award from having collateral-estoppel effect. No. 22-50788 (July 12, 2023).

along with some additional explanation of the difference between a “reasoned award” and “Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law.” The Fifth Circuit rejected the argument that the arbitrator’s drawing of this distinction kept the award from having collateral-estoppel effect. No. 22-50788 (July 12, 2023).

Dream Medical Group v. Old South Trading Co. reminds how hard it is to challenge the merits of an arbitration award.

Dream Medical Group v. Old South Trading Co. reminds how hard it is to challenge the merits of an arbitration award.

Dream Medical bought medical face masks from Old South. They had a contract dispute that went to arbitration with the AAA. Dream Medical won and Old South opposed confirmation.

Among other arguments, Old South complained that its fraudulent-inducement claim was mishandled, in that the panel violated a AAA rule by not fully considering Old South’s fraudulent-inducement claim, and thus came within the FAA’s provision about arbitrators who “exceeded their powers.”

The Fifth Circuit rejected that argument as an invitation for us to reasses the merits of the Panel’s decision.” It also noted that “manifest disregard of the law” is not a viable, nonstatutory basis for opposing confirmation under Fifth Circuit precedent. No. 22-20286 (March 6, 2023) (unpublished).

Addressing a basic but delicate issue about franchise law, the Fifth Circuit stated its test for enforcement of an arbitration agreement based on “close relationship” principles in Franlink Inc. v. BACE Servcs., Inc.:

Borrowing from the precedents, including the Third and Seventh Circuits, we extract a few fundamental factors applicable here that we will consider in determining whether these nonsignatories are closely related: (1) common ownership between the signatory and the non-signatory, (2) direct benefits obtained from the contract at issue, (3) knowledge of the agreement generally and (4) awareness of the forum selection clause particularly. Of course, the closely-related doctrine is context specific and is determined only after weighing the significance of the facts relevant to the particular case at hand.

No. 21-20316 (Sept. 28, 2022) (citations omitted, emphasis added).

The well-known poem Antigonish begins:

Yesterday, upon the stair,

I met a man who wasn’t there

He wasn’t there again today

I wish, I wish he’d go away.

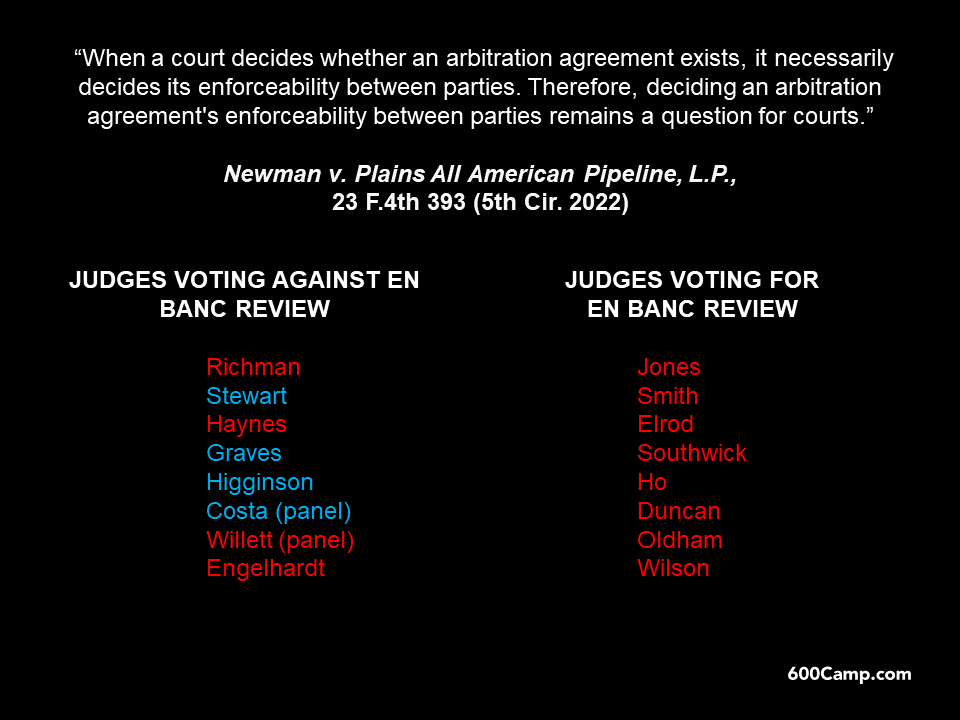

In that general spirit, in recent days, both the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and the Court of Appeals for the Fifth District at Dallas had close en banc votes involving questions of arbitrability, as to a party who “wasn’t there”–who had not signed an arbitration agreement, but was nevertheless potentially subject to it. (The Dallas case is discussed here; the Fifth Circuit’s, here.)

Whether the timing is an example of synchronicity I will leave to others. The courts’ difficulty with these issues shows the strong feelings provoked by the issue of court access, even among very sophisticated jurists, in an area of the law with well-developed case law on many key points.

By an 8-8 vote over a dissent, the full Fifth Circuit declined to review Newman v. Plains All Am. Pipeline, L.P., a case about a court’s power to determine arbitrability when a nonsignatory seeks to enforce an arbitration clause. The breakdown of votes was as follows (Senior Judge King was the third panel member):

By an 8-8 vote over a dissent, the full Fifth Circuit declined to review Newman v. Plains All Am. Pipeline, L.P., a case about a court’s power to determine arbitrability when a nonsignatory seeks to enforce an arbitration clause. The breakdown of votes was as follows (Senior Judge King was the third panel member):

Preble-Rich, a Haitian company, had a contract with a Haitian government agency to deliver fuel. A payment dispute developed and Preble-Rich started an arbitration in New York, pursuant to a broad clause in the parties’ contract (“In the event of a dispute between the [Parties] under this Contract, the dispute shall be submitted by either party to arbitration in New York. … The decision of the arbitrators shall be final, conclusive and binding on all Parties. Judgment upon such award may be entered in any court of competent jurisdiction.”).

Preble-Rich, a Haitian company, had a contract with a Haitian government agency to deliver fuel. A payment dispute developed and Preble-Rich started an arbitration in New York, pursuant to a broad clause in the parties’ contract (“In the event of a dispute between the [Parties] under this Contract, the dispute shall be submitted by either party to arbitration in New York. … The decision of the arbitrators shall be final, conclusive and binding on all Parties. Judgment upon such award may be entered in any court of competent jurisdiction.”).

Preble-Rich obtained “a partial final award of security” from the arbitration panel requiring the posting of $23 million in security. Litigation to enforce that award led to Preble-Rish Haiti, S.A. v. Republic of Haiti, No. 22-20221, which held that the above clause was not an explicit waiver of immunity from attachment as required by the Foreign Sovereign Immunity Act, 28 U.S.C. § 1610(d). “The arbitration clause is relevant to whether BMPAD waived its sovereign immunity from suit generally, but a waiver of immunity from suit has ‘no bearing upon the question of immunity from prejudgment attachment.’” (citation omitted).

Important arbitration-waiver case today from SCOTUS:

Important arbitration-waiver case today from SCOTUS:

“Most Courts of Appeals have answered that question by applying a rule of waiver specific to the arbitration context. Usually, a federal court deciding whether a litigant has waived a right does not ask if its actions caused harm. But when the right concerns arbitration, courts have held, a finding of harm is essential: A party can waive its arbitration right by litigating only when its conduct has prejudiced the other side. That special rule, the courts say, derives from the FAA’s ‘policy favoring arbitration.’ We granted certiorari to decide whether the FAA authorizes federal courts to create such an arbitration-specific procedural rule. We hold it does not.”

Morgan v. Sundance Inc., No. 21-328 (May 23, 2022).

Badgerow v. Walters recently returned to the Fifth Circuit after the Supreme Court’s clarification that a “‘look-through’ approach to determining federal jurisdiction does not apply to requests to confirm or vacate arbitral awards under Sections 9 and 10 of the FAA.” No. 19-30766 (May 11, 2022).

Badgerow v. Walters recently returned to the Fifth Circuit after the Supreme Court’s clarification that a “‘look-through’ approach to determining federal jurisdiction does not apply to requests to confirm or vacate arbitral awards under Sections 9 and 10 of the FAA.” No. 19-30766 (May 11, 2022).

The Urban Dictionary associates the phrase “been had” with the buyer of an unintendedly green ring. The Fifth Circuit associates the phrase with the “buyer” of a JAMS arbitration:

Here the parties’ arbitration agreements called for arbitration pursuant to JAMS Comprehensive Arbitration Rules and Procedures, which included the right of JAMS to terminate the arbitration proceedings for nonpayment of fees by any party. Exercising this right, JAMS terminated the arbitration proceeding following the Fund’s nonpayment. Following the lead of our sister circuits, we conclude that arbitration ‘has been had.’ Even though the arbitration did not reach the final merits and was instead terminated because of a party’s failure to pay its JAMS fees, the parties still exercised their contractual right to arbitrate prior to judicial resolution in accordance with the terms of their agreements.

Noble Capital Fund Mgmnt. LLC v. US Capital, No. 21-50609 (April 13, 2022) (footnotes omitted) (emphasis added).

“To be sure, the order on appeal is the district court’s order denying Doe’s motion to re-open the case and sever the cost-splitting provision of the arbitration agreement—not its order compelling arbitration. But that makes no difference for our purposes. As both parties acknowledge, Doe’s motion to re-open and sever was, in effect, nothing more than a motion to reconsider the merits of part of the district court’s order compelling arbitration. And we have no more jurisdiction to review an order declining to reconsider an order compelling arbitration than we do to review the order compelling arbitration itself.” Doe v. Tonti Mgmnt. Co., No. 21-30295 (Jan. 31, 2022).

In Newman v. Cypress Env. Mgmnt.:

- Newman, a pipeline inspector, had an Employment Agreement with Cypress, a business that supplied pipeline inspectors for client projects, and that agreement had an arbitration clause;

- A Cypress affiliate entered a contract to supply services to Plains, a pipeline company

- Newman brought an FLSA action against Plains for unpaid overtime, and Plains sought to compel arbitration, citing the provision of the Newman-Cypress contract.

The Fifth Circuit held that Plains was not a third-party beneficiary of that contract and could not enforce it, noting: “First, Newman’s incorporated-by-reference Pay Letter [between the Cypress affiliate and Plains] did not clearly and fully spell out that Plains could take legal action if either Newman or Cypress breached its terms. To the extent that it named Plains at all, the Pay Letter merely list ‘Plains-Pipeline’ as the ‘Client.’ … [and] Second, the Employment Agreement itself did not clearly and fully spell out that Plains could take legal action if Newman decided to breach its other terms.” No. 21-5023 (Jan. 7, 2022) (emphasis in original).

“Federal courts can enforce an arbitration agreement only if they could hear the underlying ‘controversy between the parties.’ 9 U.S.C. § 4. In Vaden v. Discover Bank, 556 U.S. 49 (2009), the court told us to define that ‘controversy’ by looking to the whole dispute, including any state-court pleadings.” ADT, LLC v. Richmond, No. 21-10023 (Nov. 10, 2021).

ADT presented the question whether that technique for definition also applies to the parties in the case–a material issue in that case, because federal diversity jurisdiction over the arbitration suit depended on how the court treated nondiverse parties in the underlying state-court lawsuit.

The Fifth Circuit concluded that Vaden did not apply,, based on the plain language of section 4: “Having agreed to arbitrate its claims against a diverse defendant, a plaintiff may not escape our power by joining to its state-court suit nondiverse persons whom it could not hale into arbitration. ‘Parties,’ in § 4, means the parties to the § 4 suit–not everyone against whom one party claims relief.” (emphasis added).

In Gezu v. Charter Communications, “the record show[ed] a valid modification to [plaintiff’s] employment contract–i.e., notice and acceptance,” when:

- Notice. “On October 6, 2017, Charter sent an email notice to Gezu of its new Program aimed at ‘efficiently resolv[ing] covered employment-related legal disputes through binding arbitration.’ … The email stated that by participating, the recipient and Charter ‘both waive[d] the right to initiate or participate in court litigation … involving a covered claim’ and that recipients ‘would be automatically enrolled in the Program unless they chose to ‘opt out of participating … within … 30 days.’ This language, along with the referenced links to additional information about the Program provided in the email, was sufficient to notify Gezu unequivocally of the arbitration agreement.” (emphasis added); and

- Acceptance. “The October 6, 2017 email ‘conspicuously warned that employees were deemed to accept’ the Program unless they opted out within 30 days. In re Dillard Dep’t Stores, Inc., 198 S.W.3d 778, 780 (Tex. 2006). The email also provided recipients with directions on how to opt out. Nonetheless, Gezu did not opt out of the Program and continued working for Charter for over a year until he was terminated in May 2019.”

No. 21-10198 (Nov. 2, 2021).

Forby v. One Technologies presented the unusual situation of an arbitration waiver by the defendant, followed by an arbitration waiver the plaintiff as to a newly asserted claim: “We again address a class action claiming that One Technologies, L.P. (“One Tech”), duped consumers into signing up for ‘free’ credit reports that were not really free. The last time around, we ruled One Tech waived its right to arbitrate the plaintiffs’ state-law claims. Forby v. One Technologies., 909 F.3d 780 (5th Cir. 2018) [hereinafter Forby I]. Now, we consider whether One Tech also waived its right to arbitrate federal claims added after remand. Adhering to our precedent that waivers of arbitral rights are evaluated on a claim-by-claim basis, see Subway Equip. Leasing Corp. v. Forte, 169 F.3d 324, 328 (5th Cir. 1999), we hold that One Tech did not waive its right to arbitrate the new federal claims.” No. 20-10088 (Sept. 14, 2021) (citing, inter alia, Collado v. J&G Transp., Inc., 820 F.3d 1256 (11th Cir. 2016)).

Forby v. One Technologies presented the unusual situation of an arbitration waiver by the defendant, followed by an arbitration waiver the plaintiff as to a newly asserted claim: “We again address a class action claiming that One Technologies, L.P. (“One Tech”), duped consumers into signing up for ‘free’ credit reports that were not really free. The last time around, we ruled One Tech waived its right to arbitrate the plaintiffs’ state-law claims. Forby v. One Technologies., 909 F.3d 780 (5th Cir. 2018) [hereinafter Forby I]. Now, we consider whether One Tech also waived its right to arbitrate federal claims added after remand. Adhering to our precedent that waivers of arbitral rights are evaluated on a claim-by-claim basis, see Subway Equip. Leasing Corp. v. Forte, 169 F.3d 324, 328 (5th Cir. 1999), we hold that One Tech did not waive its right to arbitrate the new federal claims.” No. 20-10088 (Sept. 14, 2021) (citing, inter alia, Collado v. J&G Transp., Inc., 820 F.3d 1256 (11th Cir. 2016)).

The defendant in IMA, Inc. v. Medical City Dallas sought to compel arbitration under a “direct-benefits estoppel” theory. It argued that the plaintiff’s claim, which involved a series of related contracts, necessarily implicated an agreement that contained an arbitration clause. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the denial of its motion to compel arbitration, agreeing that the defendant lacked “knowledge of the contract’s ‘basic terms,’ and noting: “IMA neither was shown to have, nor needed, knowledge of the Hospital Agreement in order to fulfill its obligations to the Health Plan and the IMAPPOplus Agreement; rather IMA could process the claims with ‘a copy of the [Health] Plan and the PPO Contract Rates.'” No. 20-20032 (June 17, 2021).

The defendant in IMA, Inc. v. Medical City Dallas sought to compel arbitration under a “direct-benefits estoppel” theory. It argued that the plaintiff’s claim, which involved a series of related contracts, necessarily implicated an agreement that contained an arbitration clause. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the denial of its motion to compel arbitration, agreeing that the defendant lacked “knowledge of the contract’s ‘basic terms,’ and noting: “IMA neither was shown to have, nor needed, knowledge of the Hospital Agreement in order to fulfill its obligations to the Health Plan and the IMAPPOplus Agreement; rather IMA could process the claims with ‘a copy of the [Health] Plan and the PPO Contract Rates.'” No. 20-20032 (June 17, 2021).

A party in Int’l Energy Ventures Mgmnt, LLC v. United Energy Group, Ltd. “recognize[d] the general proposition that litigation-conduct waiver is an issue that should be decided by the court,” but “contend[ed] that the general rule does not apply here for three reasons.” The Fifth Circuit rejected each one:

- Incorporation of AAA rules. Yes, the parties’ agreement gave the arbitrator “the power to rule on its own jurisdiction,” but it did not “clearly and unmistakably” confer the power to decided litigation-conduct waiver.

- Waiver. Again, the Court found that activity during the arbitration did not “clearly and unmistakably” result in the “submission” of this issue, noting reservations made by the relevant party and the arbitrator’s own actions.

- “Unique facts.” The Court did not find key cases inapplicable because of the party who sought arbitration: “‘Arbitration is a matter of contract,'” reasoned the Court, and “[e]xtra-contractual factors–like where an issue first arises and who initiates arbitration–are not part of the interpretive analysis.”

No. 20-20221 (May 28, 2021).

In an arbitrability dispute, the Fifth Circuit reviewed the basis for federal jurisdiction, noting: “[Vaden v. Discover Bank, 556 U.S. 49 (2009)] then went on to point out a wrinkle. ‘As for jurisdiction over controversies touching arbitration, however, the [Federal Arbitration] Act is something of an anomaly in the realm of federal legislation: It bestows no federal jurisdiction but rather requires for access to a federal forum an independent jurisdictional basis over the parties’ dispute.'” Applied to the case at hand: “Under that “look through” analysis, we hold that this underlying dispute presents a federal question. Polyflow’s arbitration demand included at least three federal statutory claims under the Lanham Act …. What matters is that a federal question—the Lanham Act claims—animated the underlying dispute, not whether Polyflow listed them in its original complaint.” Polyflow LLC v. Specialty RTP LLC, No. 20-20416 (March 30, 2021).

In an arbitrability dispute, the Fifth Circuit reviewed the basis for federal jurisdiction, noting: “[Vaden v. Discover Bank, 556 U.S. 49 (2009)] then went on to point out a wrinkle. ‘As for jurisdiction over controversies touching arbitration, however, the [Federal Arbitration] Act is something of an anomaly in the realm of federal legislation: It bestows no federal jurisdiction but rather requires for access to a federal forum an independent jurisdictional basis over the parties’ dispute.'” Applied to the case at hand: “Under that “look through” analysis, we hold that this underlying dispute presents a federal question. Polyflow’s arbitration demand included at least three federal statutory claims under the Lanham Act …. What matters is that a federal question—the Lanham Act claims—animated the underlying dispute, not whether Polyflow listed them in its original complaint.” Polyflow LLC v. Specialty RTP LLC, No. 20-20416 (March 30, 2021).

The question whether “manifest disregard of the law” allows a court to vacate an arbitration award lingered in the case law since Hall Street Assocs. v. Mattel, Inc., 552 U.S. 576 (2008), which held that an arbitration agreement cannot create a ground for vacatur or modification beyond those set out in the FAA.

The question whether “manifest disregard of the law” allows a court to vacate an arbitration award lingered in the case law since Hall Street Assocs. v. Mattel, Inc., 552 U.S. 576 (2008), which held that an arbitration agreement cannot create a ground for vacatur or modification beyond those set out in the FAA.

Jones v. Michaels Stores provided “an opportunity to resolve at least one thing that we have directly resolved [about Hall Street]: ‘manifest disregard of the law as an independent, nonstatutory ground for setting aside an award must be abandoned and rejected.” No. 20-30428 (March 15, 2021) (quoting Citigroup Global Markets, Inc. v. Bacon, 562 F.3d 349, 358 (5th Cir. 2009)).

But what of McKool Smith, P.C. v. Curtis Int’l, Ltd., 650 F. App’x 208 (5th Cir. 2016) (per curiam)? Jones clarified that McKool Smith was a case “in which a party argued that an arbitrator’s manifest disregard of the law showed that he had ‘exceeded [his] powers within the meaning of 9 U.S.C. § 10(a)(4).” In that case, “[b]eecause of uncertainty about whether the manifest-disregard standard could still be used as a means of establishing one of the statutory factors, McKool Smith assumed arguendo that it could because the standard was not met in any event.” In this case, however, “[a]s Jones does not invoke any statutory ground for vacatur, Citigroup Global was dispositive of Jones’s challenge to the arbitration award.

The Fifth Circuit reversed on an issue about arbitrator disclosure, observing, inter alia: “OOGC hypothesizes that these possible, incidental harms to FTS flowing from a unanimous arbitration panel ruling would make [the arbitrator] think that he needed to rule in FTS’s favor or else it would take him personally to task by declining to retain him in future matters. This is simply too much conjecture. Accepting OOGC’s argument would create an ‘incentive to conduct intensive, after-the-fact investigations to discover the most trivial of relationships,’ undercutting the purpose of arbitration ‘as an

efficient and cost-effective alternative to litigation.'” OOGC America v. Chesapeake Exploration, No. 19-20002 (Sept. 14, 2020).

A dispute about an allegedly malfunctioning power generator led to an ingenious but flawed attempt to resolve it in Imperial Indus. Supply Co. v.. Thomas, in two steps:

A dispute about an allegedly malfunctioning power generator led to an ingenious but flawed attempt to resolve it in Imperial Indus. Supply Co. v.. Thomas, in two steps:

- “[Thomas] began by sending Imperial a document titled “ConditionalAcceptance for the Value/For Proof of Claim/Agreement” (“Alleged Agreement”) which purported to be a “binding self-executing irrevocable contractual agreement” evidencing Thomas’s acceptance of Imperial’s offer. , , , The Alleged Agreement further provided that Imperial would need to propound fifteen different “Proofs of Claim” to Thomas in order to avoid (1) breaching the Alleged Agreement; (2) admitting, by “tacit acquiescence,” that the generator caused the fire; and (3) participating in arbitration proceedings.”

- “Then, Thomas sent Imperial two notices related to the Alleged Agreement. The first notice purported that Imperial breached the Alleged Agreement by failing to provide the proofs of claim. This notice allowed Imperial to cure the alleged breach by providing the proofs of claim within three days. In addition, the notice stated that Imperial’s refusal to follow the curing mechanism would result in Imperial’s admission and confessed judgment to the alleged breach. The second notice stated that Imperial owed the balance for the “entire contract value”1 because it did not cure the breach.”

Thomas than obtained a favorable arbitration award against Imperial. Unimpressed, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the district court’s order that vacated the award, noting: “If Thomas’s argument was valid, it would turn the notion of mutual assent on its head in ordinary purchase cases like this one: buy an item from a dealer or manufacturer, then mail a letter saying “you agree if you don’t object,” and you can have whatever deal you want if the dealer/manufacturer doesn’t respond. Thomas fails to cite a single case that would support such a ridiculous notion.” No. 20-60121 (Sept. 2, 2020).

The parties’ arbitration agreement adopted certain AAA rules; among them, Rule 52(e) says: “Parties to an arbitration under these rules may not call the arbitrator . . . as a witness in litigation or any other proceeding relating to the arbitration” and that an arbitrator is “not competent to testify as [a] witness[] in such proceeding.”

The parties’ arbitration agreement adopted certain AAA rules; among them, Rule 52(e) says: “Parties to an arbitration under these rules may not call the arbitrator . . . as a witness in litigation or any other proceeding relating to the arbitration” and that an arbitrator is “not competent to testify as [a] witness[] in such proceeding.”

The appellant in Vantage Deepwater Co. v. Petrobras, facing an award of close to $700 million, sought the deposition of the dissenter on a 3-judge panel, noting his unusual statement that “the entire arbitration, ‘the prehearing, hearing, and posthearing processes,’ denied Petrobras ‘fundamental fairness and due process protections.'”

The Fifth Circuit held otherwise: “We have not discovered any court of appeals decision holding that a district court abused its discretion in denying discovery from an arbitrator about the substance of the award. We see nothing in this record to cause us to be the first.” No. 19-20435 (July 16, 2020).

O’Shaughnessy v. Young Living Essential Oils presents the classic contract-law problem of an agreement contained in more than one document; here, it led to the Fifth Circuit rejecting the defendant’s effort to compel arbitration. O’Shaughnessey’s “Member Agreement” with Young Living had three salient features:

O’Shaughnessy v. Young Living Essential Oils presents the classic contract-law problem of an agreement contained in more than one document; here, it led to the Fifth Circuit rejecting the defendant’s effort to compel arbitration. O’Shaughnessey’s “Member Agreement” with Young Living had three salient features:

- A “Jurisdiction and Choice of Law” clause – “The Agreement will be interpreted and construed in accordance with the laws of the State of Utah applicable to contracts to be performed therein. Any legal action concerning the Agreement will be brought in the state and federal courts located in Salt Lake City, Utah.”

- A merger clause – “The Agreement constitutes the entire agreement between you and Young Living and supersedes all prior agreements; and no other promises,

representations, guarantees, or agreements of any kind will be valid unless in writing and signed by both parties.” - And it incorporated by reference a “Policies and Procedures” document.

The Policies and Procedures, in turn, had an arbitration clause with a carve-out for certain kinds of injunctive relief. The Court held: “The arbitration clause’s exemption of certain litigatory rights from its purview does not cure its inherent conflict with the Jurisdiction and Choice of Law provision. The two provisions irreconcilably conflict and for this reason, we agree that there was no ‘meeting of the minds’ with respect to arbitration in this case.” No. 19-51169 (April 28, 2020). (The above picture, BTW, is Mary Astor playing Brigid O’Shaughnessey in 1941’s The Maltese Falcon.)

After recently addressing a party’s rights to oral argument in a dispute about enforcement of an arbitration award, the Fifth Circuit then returned to Sun Coast Resources v. Conrad to review the prevailing party’s motion for sanctions under Fed. R. App. 38 for a frivolous appeal.The Court observed:

After recently addressing a party’s rights to oral argument in a dispute about enforcement of an arbitration award, the Fifth Circuit then returned to Sun Coast Resources v. Conrad to review the prevailing party’s motion for sanctions under Fed. R. App. 38 for a frivolous appeal.The Court observed:

“[T]he case for Rule 38 sanctions is strongest in matters involving malice, not incompetence. And our decision on Sun Coast’s appeal was careful not to assume the former. As to the merits of its appeal—including the company’s

failure to disclose that it cited Opalinski II rather than Opalinski I to the arbitrator—we observed that ‘[t]he best that may be said for Sun Coast is that it badly misreads the record.’ As to its demand for oral argument, we stated that ‘Sun Coast’s motion misunderstands the federal appellate process in more ways than one.’

Perhaps Sun Coast earnestly (if mistakenly) believed it had a valid legal claim to press. Or perhaps it was bad faith—maximizing legal expense to drive a less-resourced adversary to drop the case or settle for less. Or perhaps its decisions were driven by counsel. But we must resolve the pending motion based on facts and evidence—not speculation. We sympathize with Conrad . . . [b]ut we conclude that this is a time for grace, not punishment.”

No. 19-20058 (May 7, 2020) (citations omitted).

While the timing is coincidental, the case is an instructive companion to the Texas Supreme Court’s recent opinion in Brewer v. Lennox Hearth Products LLC, which reversed a sanctions award. That Court noted that “while the absence of authoritative guidance is not a license to act with impunity, bad faith is required to impose sanctions under the court’s inherent authority,” and this held that “the sanctions order in this case cannot stand because evidence of bad faith is lacking.” No. 18-0426 (Tex. April 24, 2020) (footnotes omitted).

Sun Coast Resources Inc. v. Conrad, No. 19-20058 (April 16, 2020), involved a challenge to an arbitration award. The challenging party did not agree with the Fifth Circuit’s decision to proceed without oral argument, and filed a motion seeking an oral argument. It was denied and the Court’s explanation is instructive:

Sun Coast Resources Inc. v. Conrad, No. 19-20058 (April 16, 2020), involved a challenge to an arbitration award. The challenging party did not agree with the Fifth Circuit’s decision to proceed without oral argument, and filed a motion seeking an oral argument. It was denied and the Court’s explanation is instructive:

- “Sun Coast’s motion misunderstands the federal appellate process in

more ways than one. To begin, the motion claims that ‘oral argument is the

norm rather than the exception.’ Not true. ‘More than 80 percent of federal

appeals are decided solely on the basis of written briefs. Less than a quarter

of all appeals are decided following oral argument.'”; - “Sun Coast suggests that deciding this case without oral argument would be ‘akin to . . . cafeteria justice.’ The Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure state otherwise. They authorize “a panel of three judges who have examined the briefs and record” to ‘unanimously agree[] that oral argument is unnecessary for any of the following reasons”—such as the fact that “the dispositive issue or issues have been authoritatively decided,” or that “the facts and legal arguments are adequately presented in the briefs and record, and the decisional process would not be significantly aided by oral argument.””; and

- “[A]nother tactic powerful economic interests sometimes use against

the less resourced is to increase litigation costs in an attempt to bully the

opposing party into submission by war of attrition—for example, by filing a

meritless appeal of an arbitration award won by the economically weaker

party, and then maximizing the expense of litigating that appeal. Dispensing with oral argument where the panel unanimously agrees it is unnecessary, and where the case for affirmance is so clear, is not cafeteria justice—it is simply justice.” (citations omitted and emphasis added in all the above quotes).

The arbitration clause in Bowles’s employment contract had a provision delegating to the arbitrator, “any legal dispute . . . arising out of, relating to, or concerning the validity, enforceability or breach of this Agreement, shall be resolved by final and binding arbitration.” Bowles argued that disparity of bargaining power during her contract negotiations amounted to procedural unconscionability. “Bowles’s challenge to the Arbitration Agreement as procedurally unconscionable was a challenge to the Agreement’s enforceability, not to its existence. For that reason, under the delegation clause in the Agreement that sends all enforcement challenges to an arbitrator, the district court correctly referred this challenge to the arbitrator.” Bowles v. OneMain Fin. Group, No. 18-60749 (April 2, 2020).

A union protested that an arbitrator, in the guise of correcting a “technical” error with his original award, in fact revised its substance in a way contrary to the applicable arbitration rules. The Fifth Circuit disagreed: “To the contrary, he cited [AAA] Rule 40, classified his error as a “technical” one capable of correction, and held that his correction did not violate Rule 40, notwithstanding the Union’s argument that he was “redetermin[ing] the merits” of CWA’s claim against the Company. Even if the arbitrator made a mistake in reaching his conclusion, “[t]he potential for . . . mistakes is the price of agreeing to arbitration. . . . The arbitrator’s construction holds, however good, bad, or ugly.” Communication Workers of America v. Southwestern Bell, No. 19-50686 (March 27, 2020) (citations omitted).

A union protested that an arbitrator, in the guise of correcting a “technical” error with his original award, in fact revised its substance in a way contrary to the applicable arbitration rules. The Fifth Circuit disagreed: “To the contrary, he cited [AAA] Rule 40, classified his error as a “technical” one capable of correction, and held that his correction did not violate Rule 40, notwithstanding the Union’s argument that he was “redetermin[ing] the merits” of CWA’s claim against the Company. Even if the arbitrator made a mistake in reaching his conclusion, “[t]he potential for . . . mistakes is the price of agreeing to arbitration. . . . The arbitrator’s construction holds, however good, bad, or ugly.” Communication Workers of America v. Southwestern Bell, No. 19-50686 (March 27, 2020) (citations omitted).

An unsuccessful motion to compel arbitration did not fare better on appeal when:

- The question of who decides arbitrability was not raised in the motion (and was thus forfeited for appeal purposes);

- Equitable estoppel was briefed in the motion with reference to authority about “concerted misconduct estoppel” – theory rejected by the Texas Supreme Court;

- Direct benefits estoppel was unavailable because the plaintiffs sued under federal employment law, not their state-law employment agreements;

- Third party beneficiary status was not available because the movant was not named in the agreement, while the entity that actually had hired the plaintiffs was.

Hiser v. NZone Guidance LLC, No. 19-50353 (March 24, 2020) (unpublished).

The arbitration clause in Kemper Corporate Servcs., Inc. v. Computer Sciences Corp., No. 18-11276 (Jan. 10, 2020), said that “decisions shall be in writing and shall state the findings of fact and conclusions of law upon which the decision is based, provided that such decision may not (i) award consequential, punitive, special, incidental or exemplary damages or any amounts in excess of the limitations delineated in” other provisions of the parties’ contracts (emphasis added). The unsuccessful party questioned whether the arbitrator had authority to “categorize damages as consequential or direct,” but the Fifth Circuit disagreed, concluding: “For the arbitrator to resolve the dispute between CSC and Kemper, which could include awarding damages, he had to categorize the potential damages into the permitted and the prohibited categories.” The Court then affirmed under the highly-deferential standard of review as stated in BNSF R.R. Co. v. Alstom Transp., 777 F.3d 785 (5th Cir. 2015).

The arbitration clause in Kemper Corporate Servcs., Inc. v. Computer Sciences Corp., No. 18-11276 (Jan. 10, 2020), said that “decisions shall be in writing and shall state the findings of fact and conclusions of law upon which the decision is based, provided that such decision may not (i) award consequential, punitive, special, incidental or exemplary damages or any amounts in excess of the limitations delineated in” other provisions of the parties’ contracts (emphasis added). The unsuccessful party questioned whether the arbitrator had authority to “categorize damages as consequential or direct,” but the Fifth Circuit disagreed, concluding: “For the arbitrator to resolve the dispute between CSC and Kemper, which could include awarding damages, he had to categorize the potential damages into the permitted and the prohibited categories.” The Court then affirmed under the highly-deferential standard of review as stated in BNSF R.R. Co. v. Alstom Transp., 777 F.3d 785 (5th Cir. 2015).

Catic USA challenged a $63 million arbitration award about a Chinese wind-energy venture, complaining inter alia, that the panel was assembled unfairly: “[O]ne side (the plaintiffs) appointed five arbitrators, the other side (Catic USA and Thompson) only two.'” The Fifth Circuit disagreed, noting that the parties’ contract identified “seven total, signatory ‘Members,'” each of whom had the right to name an arbitrator in the event of a dispute. “This case involves two sides, but, more importantly, it features seven members; suppose Eris had tossed the Apple of Discord into a Soaring Wind conference room, prompting a free-for-all among the parties–the arbiter selection process would have remained the same.” Soaring Wind Energy LLC v. Catic USA Inc., No. 18-11192 (Jan. 7, 2020). The Court reminded that as a general matter: “It is not the court’s role to rewrite the contract between sophisticated market participants, allocating the risk of an agreement after the fact, to suit the court’s sense of equity or fairness.”

Catic USA challenged a $63 million arbitration award about a Chinese wind-energy venture, complaining inter alia, that the panel was assembled unfairly: “[O]ne side (the plaintiffs) appointed five arbitrators, the other side (Catic USA and Thompson) only two.'” The Fifth Circuit disagreed, noting that the parties’ contract identified “seven total, signatory ‘Members,'” each of whom had the right to name an arbitrator in the event of a dispute. “This case involves two sides, but, more importantly, it features seven members; suppose Eris had tossed the Apple of Discord into a Soaring Wind conference room, prompting a free-for-all among the parties–the arbiter selection process would have remained the same.” Soaring Wind Energy LLC v. Catic USA Inc., No. 18-11192 (Jan. 7, 2020). The Court reminded that as a general matter: “It is not the court’s role to rewrite the contract between sophisticated market participants, allocating the risk of an agreement after the fact, to suit the court’s sense of equity or fairness.”

“The district court’s order to stay and administratively close [Appellant]’s case is not a final order for purposes of [Federal Arbitration Act] § 16(a)(3); the collateral order doctrine does not apply to orders concerning arbitration governed by the FAA; and § 1292(a)(3) is inapplicable to referrals to arbitration in admiralty cases that do not determine a party’s substantive rights or liabilities.” Psara Energy, Ltd. v. Advantage Arrow Shipping, LLC, No. 19-40071 (Jan. 9, 2020).

“The district court’s order to stay and administratively close [Appellant]’s case is not a final order for purposes of [Federal Arbitration Act] § 16(a)(3); the collateral order doctrine does not apply to orders concerning arbitration governed by the FAA; and § 1292(a)(3) is inapplicable to referrals to arbitration in admiralty cases that do not determine a party’s substantive rights or liabilities.” Psara Energy, Ltd. v. Advantage Arrow Shipping, LLC, No. 19-40071 (Jan. 9, 2020).

Walker and Ameriprise Financial, pursuant to their agreement, arbitrated their dispute under FINRA rules. Walker argued that the panel “exceeded its powers,” and thus fell within a statutory ground for vacatur of the arbitration award. The Fifth Circuit disagreed: “’An arbitrator exceeds his powers [under § 10(a)(4)] if he acts contrary to express contractual provisions.’ Walker does not argue that the panel violated any express provisions of the arbitration agreement, but only that it incorrectly applied [FINRA] Rule 13504.” Walker v. Ameriprise Fin. Servcs., Inc., No. 18-11641 (Oct. 9, 2019) (unpublished).

Walker and Ameriprise Financial, pursuant to their agreement, arbitrated their dispute under FINRA rules. Walker argued that the panel “exceeded its powers,” and thus fell within a statutory ground for vacatur of the arbitration award. The Fifth Circuit disagreed: “’An arbitrator exceeds his powers [under § 10(a)(4)] if he acts contrary to express contractual provisions.’ Walker does not argue that the panel violated any express provisions of the arbitration agreement, but only that it incorrectly applied [FINRA] Rule 13504.” Walker v. Ameriprise Fin. Servcs., Inc., No. 18-11641 (Oct. 9, 2019) (unpublished).

The district court held a jury trial on whether Gilbert Galan had notice of Valero Energy’s (his employer) arbitration program. Valero called the arbitation program “Dialogue”; the jury charge asked whether “Valero prove[d] by a preponderance of the evidence that it gave unequivocal notice  to Gilbert Galan, Jr. of definite changes in employment terms regarding Valero’s Dialogue program[,]” Additionally, an instruction said that the “sole issue in this trial is whether Defendant[] Valero . . . notified plaintiff of the arbitration program and its mandatory nature.” Galan objected that the question did not have the word “arbitration”; “[h]is point is that the jury could have concluded Galan knew about the Dialogue Program as a whole, but not the part of it requiring arbitration.” The Fifth Circuit found no abuse of discretion in denying that request, especially given the instruction accompanying the question. Galan v. Valero Services, Inc., No. 19-400753 (Sept. 23, 2019) (unpublished).

to Gilbert Galan, Jr. of definite changes in employment terms regarding Valero’s Dialogue program[,]” Additionally, an instruction said that the “sole issue in this trial is whether Defendant[] Valero . . . notified plaintiff of the arbitration program and its mandatory nature.” Galan objected that the question did not have the word “arbitration”; “[h]is point is that the jury could have concluded Galan knew about the Dialogue Program as a whole, but not the part of it requiring arbitration.” The Fifth Circuit found no abuse of discretion in denying that request, especially given the instruction accompanying the question. Galan v. Valero Services, Inc., No. 19-400753 (Sept. 23, 2019) (unpublished).

The Flying Dutchman is a mythical ship that forever travels the seas, unable to find a port. Conn Appliances, Inc. v. Williams presents a similar tale about a dispute involving a retail installment contract. Williams sued Conn in Tennessee, realized that he had an arbitration agreement in his contract, and then dismissed his suit in favor of arbitration in Tennessee (the clause required arbitration “near his residence”). Williams won; he filed suit in Tennessee to enforce the award while Conn filed sued in its

The Flying Dutchman is a mythical ship that forever travels the seas, unable to find a port. Conn Appliances, Inc. v. Williams presents a similar tale about a dispute involving a retail installment contract. Williams sued Conn in Tennessee, realized that he had an arbitration agreement in his contract, and then dismissed his suit in favor of arbitration in Tennessee (the clause required arbitration “near his residence”). Williams won; he filed suit in Tennessee to enforce the award while Conn filed sued in its  home state of Texas to vacate it (the clause allowed confirmation in “any court with jurisdiction”). The Fifth Circuit agreed that Williams was not subject to personal jurisdiction in Texas, and affirmed the dismissal of that action. Conn protested that it was not subject to jurisdiction in Tennessee, and the Court observed: “[E]ven if the Western District of Tennessee is not the proper forum, the lack of jurisdiction over Conn in another forum does not mean that the Southern District of Texas has personal jurisdiction over Williams.” No. 19-20139 (Sept. 4, 2019).

home state of Texas to vacate it (the clause allowed confirmation in “any court with jurisdiction”). The Fifth Circuit agreed that Williams was not subject to personal jurisdiction in Texas, and affirmed the dismissal of that action. Conn protested that it was not subject to jurisdiction in Tennessee, and the Court observed: “[E]ven if the Western District of Tennessee is not the proper forum, the lack of jurisdiction over Conn in another forum does not mean that the Southern District of Texas has personal jurisdiction over Williams.” No. 19-20139 (Sept. 4, 2019).

A long-litigated dispute about arbitrability reached its latest stage in Archer & White Sales, Inc. v. Henry Schein, Inc., on remand from the Supreme Court, in which the Fifth Circuit held: “The most natural reading of the arbitration clause at issue here states that any dispute, except actions seeking injunctive relief, shall be resolved in arbitration in accordance with the AAA rules. The plain language incorporates the AAA rules—and therefore delegates arbitrability—for all disputes except those under the carve-out. Given that carve-out, we cannot say that the Dealer Agreement evinces a ‘clear and unmistakable’ intent to delegate arbitrability.”

A long-litigated dispute about arbitrability reached its latest stage in Archer & White Sales, Inc. v. Henry Schein, Inc., on remand from the Supreme Court, in which the Fifth Circuit held: “The most natural reading of the arbitration clause at issue here states that any dispute, except actions seeking injunctive relief, shall be resolved in arbitration in accordance with the AAA rules. The plain language incorporates the AAA rules—and therefore delegates arbitrability—for all disputes except those under the carve-out. Given that carve-out, we cannot say that the Dealer Agreement evinces a ‘clear and unmistakable’ intent to delegate arbitrability.”

As for the Supreme Court’s opinion, the panel said: “We are mindful of the Court’s reminder that ‘[w]hen the parties’ contract delegates the arbitrability question to an arbitrator, the courts must respect the parties’ decision as embodied in the contract.’ But we must also heed its warning that ‘courts “should not assume that the parties agreed to arbitrate arbitrability unless there is clear and unmistakable evidence that they did so.’”‘ The parties could have unambiguously delegated this question, but they did not, and we are not empowered to re-write their agreement.” No. 16-41674 (Aug. 16, 2019).

“Ordinarily, courts must refrain from interfering with arbitration proceedings. But as our sister circuits have held, and as we now hold today, class arbitration is a ‘gateway’ issue that must be decided by courts, not arbitrators—absent clear and unmistakable language in the arbitration clause to the contrary.” 20/20 Communications, Inc. v. Crawford, No. 1810260 (July 22, 2019).

“Ordinarily, courts must refrain from interfering with arbitration proceedings. But as our sister circuits have held, and as we now hold today, class arbitration is a ‘gateway’ issue that must be decided by courts, not arbitrators—absent clear and unmistakable language in the arbitration clause to the contrary.” 20/20 Communications, Inc. v. Crawford, No. 1810260 (July 22, 2019).

AccentCare sent an arbitration agreement to Trammell’s home; “[t]he district court applied the ‘mailbox rule’ to presume that Trammell received the company’s proffered arbitration agreement even though she testified that she never received the contract and indicated to her employer that she was experiencing difficulties in receiving and sending mail.” This showing, especially given that AccentCare could not produce a signed agreement or otherwise rebut her claims about problems with mail, the Fifth Circuit reversed: “Because Trammell created a genuine issue of material fact regarding whether an arbitration agreement was formed, she is entitled to a jury trial under Section 4 of the FAA.” Trammell v. AccentCare, Inc., No 18-50872 (June 7, 2019, unpublished).

AccentCare sent an arbitration agreement to Trammell’s home; “[t]he district court applied the ‘mailbox rule’ to presume that Trammell received the company’s proffered arbitration agreement even though she testified that she never received the contract and indicated to her employer that she was experiencing difficulties in receiving and sending mail.” This showing, especially given that AccentCare could not produce a signed agreement or otherwise rebut her claims about problems with mail, the Fifth Circuit reversed: “Because Trammell created a genuine issue of material fact regarding whether an arbitration agreement was formed, she is entitled to a jury trial under Section 4 of the FAA.” Trammell v. AccentCare, Inc., No 18-50872 (June 7, 2019, unpublished).

(The specific FAA provision, often referred to but rarely used, says: “. . . the party alleged to be in default may, except in cases of admiralty, on or before the return day of the notice of application, demand a jury trial of such issue, and upon such demand the court shall make an order referring the issue or issues to a jury in the manner provided by the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, or may specially call a jury for that purpose”).

A recurring question in commercial arbitration is the amount of detail required for a “reasoned award’ – described generally as “something short of findings and conclusions but more than a simple result.” The Fifth Court provides a helpful example in YPF S.A. v. Apache Overseas, Inc., which quotes the relevant part of the arbitrator’s award and holds: “KPMG noted that it based its analysis on the parties’ statements and accounting records, pointed to its finding on the accrual of liabilities, and explained what documentation it found relevant in evaluating the proper refund amount.” No. 17-20802 (May 24, 2019).

A recurring question in commercial arbitration is the amount of detail required for a “reasoned award’ – described generally as “something short of findings and conclusions but more than a simple result.” The Fifth Court provides a helpful example in YPF S.A. v. Apache Overseas, Inc., which quotes the relevant part of the arbitrator’s award and holds: “KPMG noted that it based its analysis on the parties’ statements and accounting records, pointed to its finding on the accrual of liabilities, and explained what documentation it found relevant in evaluating the proper refund amount.” No. 17-20802 (May 24, 2019).

While “[t]he Texas Supreme Court has not had occasion to determine whether a contract that is unsigned but otherwise enforceable may incorporate an unsigned document by reference,” that was the issue presented in Int’l Corrugated & Packing Supplies, Inc. v. Lear Corp. But in the context of an interlocutory appeal from denial of a motion to compel arbitration, the Fifth Circuit “declined[d] to resolve this novel question of Texas law here because the district court has not yet ruled on the enforceability of Lear’s purchase orders. Specifically, . . . how the parties entered the agreements at issue in this case—either through purchase orders, or phone calls or emails prior to the sending of purchase orders, or some other conduct—nor has it determined what effect, if any, the parties’ course of dealing has on such agreements [under the UCC].” No. 18-50167 (May 3, 2019) (unpublished).

While “[t]he Texas Supreme Court has not had occasion to determine whether a contract that is unsigned but otherwise enforceable may incorporate an unsigned document by reference,” that was the issue presented in Int’l Corrugated & Packing Supplies, Inc. v. Lear Corp. But in the context of an interlocutory appeal from denial of a motion to compel arbitration, the Fifth Circuit “declined[d] to resolve this novel question of Texas law here because the district court has not yet ruled on the enforceability of Lear’s purchase orders. Specifically, . . . how the parties entered the agreements at issue in this case—either through purchase orders, or phone calls or emails prior to the sending of purchase orders, or some other conduct—nor has it determined what effect, if any, the parties’ course of dealing has on such agreements [under the UCC].” No. 18-50167 (May 3, 2019) (unpublished).

An arbitration panel, organized under the rules of the Houston Bar Association, awarded a substantial sum to an attorney in a fee dispute with his former client. The client sought vacatur on the ground that it not know the non-attorney member of the panel worked for a large law firm (to paraphrase Claude Rains’s character in Casablanca, it was shocked, SHOCKED to make this discovery). The Fifth Circuit found this argument waived, and did not accept the client’s argument that waiver should be limited to vacatur based on conflicts of interest: “We therefore conclude that Light-Age waived its objection to Davis’s participation on the panel. Light-Age had constructive knowledge that Davis worked for a law firm at the time of the arbitration hearing; it could have discovered that Jackson Walker was a law firm simply by clicking on the link provided in Davis’s email signature or running a brief internet search. It is reasonable to expect even a pro se litigant to perform such basic research into its arbitrator.” Ashcroft-Smith v. Light-Age, Inc., No. 18-20098 (April 25, 2019) (emphasis added).

An arbitration panel, organized under the rules of the Houston Bar Association, awarded a substantial sum to an attorney in a fee dispute with his former client. The client sought vacatur on the ground that it not know the non-attorney member of the panel worked for a large law firm (to paraphrase Claude Rains’s character in Casablanca, it was shocked, SHOCKED to make this discovery). The Fifth Circuit found this argument waived, and did not accept the client’s argument that waiver should be limited to vacatur based on conflicts of interest: “We therefore conclude that Light-Age waived its objection to Davis’s participation on the panel. Light-Age had constructive knowledge that Davis worked for a law firm at the time of the arbitration hearing; it could have discovered that Jackson Walker was a law firm simply by clicking on the link provided in Davis’s email signature or running a brief internet search. It is reasonable to expect even a pro se litigant to perform such basic research into its arbitrator.” Ashcroft-Smith v. Light-Age, Inc., No. 18-20098 (April 25, 2019) (emphasis added).

Papalote, a wind-power producer, had a dispute with the Lower Colorado River Authority; a key issue was whether a $60 million limitation-of-liability clause applied. Their contract had an arbitration provision that applied “if any dispute arises with respect to either Party’s performance.” The Fifth Circuit found that the dispute was not subject to arbitration, as it “is a dispute related to the the interpretation of the Agreement, not a performance-related dispute . . . ..” Papalote Creek II v. Lower Colorado River Authority, No. 17-50852 (March 15, 2019).

Papalote, a wind-power producer, had a dispute with the Lower Colorado River Authority; a key issue was whether a $60 million limitation-of-liability clause applied. Their contract had an arbitration provision that applied “if any dispute arises with respect to either Party’s performance.” The Fifth Circuit found that the dispute was not subject to arbitration, as it “is a dispute related to the the interpretation of the Agreement, not a performance-related dispute . . . ..” Papalote Creek II v. Lower Colorado River Authority, No. 17-50852 (March 15, 2019).

Justice Kavanaugh’s first signed Supreme Court opinion was a 9-0 reversal of the Fifth Circuit in Schein v. Archer & White, 17-1272 (Jan. 8, 2019). The Fifth Circuit opinion found that the district court, rather than the arbitrator, could make a decision about arbitrability when the request for arbitration was “wholly groundless”; the Supreme Court rejected that line of authority and held that this language vested the arbitrator with sole authority over such disputes:

Justice Kavanaugh’s first signed Supreme Court opinion was a 9-0 reversal of the Fifth Circuit in Schein v. Archer & White, 17-1272 (Jan. 8, 2019). The Fifth Circuit opinion found that the district court, rather than the arbitrator, could make a decision about arbitrability when the request for arbitration was “wholly groundless”; the Supreme Court rejected that line of authority and held that this language vested the arbitrator with sole authority over such disputes:

“Disputes. This Agreement shall be governed by the laws of the State of North Carolina. Any dispute arising under or related to this Agreement (except for actions seeking injunctive relief and disputes related to trademarks, trade secrets, or other intellectual property of [Schein]), shall be resolved by binding ar- bitration in accordance with the arbitration rules of the American Arbitration Association [(AAA)]. The place of arbitration shall be in Charlotte, North Carolina.”

The Fifth Circuit found a waiver of the right to arbitrate in Forby v. One Technologies, finding as to the requirement of prejudice: “The district court erred in concluding that Forby failed to establish prejudice to her legal position. When a party will have to re-litigate in the arbitration forum an issue already decided by the district court in its favor, that party is prejudiced.” No.17-10883 (Nov. 28, 2018).

The Fifth Circuit found a waiver of the right to arbitrate in Forby v. One Technologies, finding as to the requirement of prejudice: “The district court erred in concluding that Forby failed to establish prejudice to her legal position. When a party will have to re-litigate in the arbitration forum an issue already decided by the district court in its favor, that party is prejudiced.” No.17-10883 (Nov. 28, 2018).

Griggs was ordered to arbitrate his dispute with Stream Energy. Griggs refused to do so. When asked by the district court for a status report, in an echo of Bartleby the Scrivener’s famous “I would prefer not to,” Griggs responded in relevant part:

Griggs was ordered to arbitrate his dispute with Stream Energy. Griggs refused to do so. When asked by the district court for a status report, in an echo of Bartleby the Scrivener’s famous “I would prefer not to,” Griggs responded in relevant part:

“Griggs anticipated that this Court would have already dismiss[ed] this case for want of prosecution because this Court left him only an arbitration which he has not pursued. So, Griggs states the following for the Court’s consideration: 1. Griggs understands and appreciates this Court’s order compelling arbitration. Griggs believes that the Court cons[idered] all arguments before it ruled. 2. However, Griggs disagrees with this Court’s conclusion that this matter must go to arbitration. 3. Griggs will not pursue arbitration. 4. Griggs stands ready to litigate this case before this Court to a conclusion.”

The district court then dismissed the case without prejudice. After review of the various kinds of dismissals addressed by Fed. R. Civ. P. 41, the Fifth Circuit treated the dismissal order as one for “delay or contumacious conduct” under Rule 41(b) – and thus, declined to reach the merits of the arbitration ruling: “Griggs should not be permitted, through recalcitrance, to obtain the review of the arbitration clause that he was expressly denied in the district court, a review that Congress has foreclosed under the Federal Arbitration Act.” Griggs v. SGE Management LLC, No. 17-50655 (Sept. 27, 2018).

Huckaba signed an arbitration agreement with her employer, Ref-Chem – but Ref-Chem did not sign the agreement. The agreement had signature blocks for both parties, referred to the “signature affixed hereto” and the legal effect of “signing this agreement,” and also said that it “may not be changed, except in writing and signed by all parties.” The Fifth Circuit concluded that the agreement was not enforceable, focusing on the distinction between acceptance of the offer, and the separate requirement of “execution and delivery of the contract with intent that it be mutual and binding.” Huckaba v. Ref-Chem, L.P., No. 17-50341 (June 11, 2018).

Huckaba signed an arbitration agreement with her employer, Ref-Chem – but Ref-Chem did not sign the agreement. The agreement had signature blocks for both parties, referred to the “signature affixed hereto” and the legal effect of “signing this agreement,” and also said that it “may not be changed, except in writing and signed by all parties.” The Fifth Circuit concluded that the agreement was not enforceable, focusing on the distinction between acceptance of the offer, and the separate requirement of “execution and delivery of the contract with intent that it be mutual and binding.” Huckaba v. Ref-Chem, L.P., No. 17-50341 (June 11, 2018).

A vigorously-litigated line  of Texas authority, often in the context of employment relationships defined by multiple documents, addresses whether an arbitration agreement is an illusory promise and thus unenforceable. In Arnold v. Homeaway, Inc. the Fifth Circuit addressed whether such a challenge went to “validity” (and could thus be resolved by an arbitrator under a “gateway” arbitration provision), or to “formation,” and could not. Drawing an analogy to Mississippi’s “minutes role” about the required documentation for contracts with public entities, the Court concluded that the challenge went to validity. Nos. 17-50088 and 17-50102 (May 15, 2018).

of Texas authority, often in the context of employment relationships defined by multiple documents, addresses whether an arbitration agreement is an illusory promise and thus unenforceable. In Arnold v. Homeaway, Inc. the Fifth Circuit addressed whether such a challenge went to “validity” (and could thus be resolved by an arbitrator under a “gateway” arbitration provision), or to “formation,” and could not. Drawing an analogy to Mississippi’s “minutes role” about the required documentation for contracts with public entities, the Court concluded that the challenge went to validity. Nos. 17-50088 and 17-50102 (May 15, 2018).

The Supreme Court has stayed further proceedings in Archer & Daniels Sales v. Henry Schein Inc., a dispute about the arbitrability of a substantial antitrust case about dental equipment. The application and response are an interesting window into this seldom-seen aspect of civil practice.

The Supreme Court has stayed further proceedings in Archer & Daniels Sales v. Henry Schein Inc., a dispute about the arbitrability of a substantial antitrust case about dental equipment. The application and response are an interesting window into this seldom-seen aspect of civil practice.

The Louisiana Department of Natural Resources complained that it was not able to call live witnesses at an arbitration with FEMA, conducted under federal regulations by the Civilian Board of Contract Appeals. Agreeing that the regulations allowed oral presentation of evidence, but also noting the fulsome written submission received without objection, the Fifth Circuit observed: “Vacatur . . . is warranted when the panel refuses to hear material, not just any, evidence; similarly, there is no indication oral presentation ‘might have altered the outcome of the arbitration.'” Louisiana Dep’t of Natural Resources v. FEMA, No. 17-30140 (Jan. 29, 2018, unpublished) (emphasis added).

The Louisiana Department of Natural Resources complained that it was not able to call live witnesses at an arbitration with FEMA, conducted under federal regulations by the Civilian Board of Contract Appeals. Agreeing that the regulations allowed oral presentation of evidence, but also noting the fulsome written submission received without objection, the Fifth Circuit observed: “Vacatur . . . is warranted when the panel refuses to hear material, not just any, evidence; similarly, there is no indication oral presentation ‘might have altered the outcome of the arbitration.'” Louisiana Dep’t of Natural Resources v. FEMA, No. 17-30140 (Jan. 29, 2018, unpublished) (emphasis added).

Plaintiffs alleged antitrust violations by distributors of dental equipment; seeking damages and injunctive relief. The defendants sought to compel arbitration, based on this arbitration clause in a relevant contract:

Plaintiffs alleged antitrust violations by distributors of dental equipment; seeking damages and injunctive relief. The defendants sought to compel arbitration, based on this arbitration clause in a relevant contract:

Disputes. This Agreement shall be governed by the laws of the State of North Carolina. Any dispute arising under or related to this Agreement (except for actions seeking injunctive relief and disputes related to trademarks, trade secrets, or other intellectual property of Pelton & Crane), shall be resolved by binding arbitration in accordance with the arbitration rules of the American Arbitration Association [(AAA)]. The place of arbitration shall be in Charlotte, North Carolina.

The issue was whether arbitrability was for the courts to decide or the arbitrator. The Fifth Circuit applied “the two-step inquiry adoped in Douglas v. Regions Bank[, 757 F.3d 460 (5th Cir. 2014),] under which the first question is whether the parties “clearly and unmistakably” intended to delegate the question of arbitrability to an arbitrator. Finding that “the interaction between the AAA Rules and the [injunctive relief] carve-out is at best ambiguous,” the Court chose not to resolve that issue, concluding that the second Douglas question was dispositive. That question asks whether the “assertion of arbitrability is wholly groundless,” which the Court found to be the case:

The arbitration clause creates a carve-out for ‘actions seeking injunctive relief.’ It does not limit the exclusion to ‘actions seeking only injunctive relief,’ nor ‘actions for injunction in aid of an arbitrator’s award.’ Nor does it limit itself to only claims for injunctive relief. . . . The mere fact that the arbitration clause allows Archer to avoid arbitration by adding a claim for injunctive relief does not change the clause’s plain meaning.

Archer & White Sales v. Henry Schein, Inc., No. 16-41674 (Dec. 21, 2017) (emphasis added).

In a 2-1 decision, the Fifth Circuit found that Ezekiel Elliott failed to exhaust remedies within the NFL’s dispute-resolution process before filing suit, meaning that the federal courts lacked subject matter jurisdiction over his complaints. A dissent found a sufficient question about the adequacy of the process to justify the exercise of jurisdiction under the relevant authorities. NFLPA v. NFL, No. 17-40936 (Oct. 12, 2017). While of enormous interest to Cowboys fans, so far as arbitration goes, the opinion is centered on issues unique to collective bargaining agreements.

In a 2-1 decision, the Fifth Circuit found that Ezekiel Elliott failed to exhaust remedies within the NFL’s dispute-resolution process before filing suit, meaning that the federal courts lacked subject matter jurisdiction over his complaints. A dissent found a sufficient question about the adequacy of the process to justify the exercise of jurisdiction under the relevant authorities. NFLPA v. NFL, No. 17-40936 (Oct. 12, 2017). While of enormous interest to Cowboys fans, so far as arbitration goes, the opinion is centered on issues unique to collective bargaining agreements.

The parties in IQ Products Co. v. WD-40 Co.disputed whether an arbitration agreement was limited to “propane/butane-propelled produicts” or also “carbon dioxide-propelled products.” The party who prevailed in the arbitration relied mainly on the parties’ subsequent conduct to justify the broader reading, and the Fifth Circuit agreed (applying California law): “Considering . . . ‘the words used . . . as well as extrinsic evidence of such objective matters and the surrounding circumstances under which the parties negotiated [and] entered into the contract; the object, nature and subject matter of the contract; and the subsequent conduct of the parties . . . WD-40’s assertion is . . . not wholly groundless.” No. 16-20595 (Sept. 13, 2017).

The parties in IQ Products Co. v. WD-40 Co.disputed whether an arbitration agreement was limited to “propane/butane-propelled produicts” or also “carbon dioxide-propelled products.” The party who prevailed in the arbitration relied mainly on the parties’ subsequent conduct to justify the broader reading, and the Fifth Circuit agreed (applying California law): “Considering . . . ‘the words used . . . as well as extrinsic evidence of such objective matters and the surrounding circumstances under which the parties negotiated [and] entered into the contract; the object, nature and subject matter of the contract; and the subsequent conduct of the parties . . . WD-40’s assertion is . . . not wholly groundless.” No. 16-20595 (Sept. 13, 2017).