Abandoning its reputation as a skeptic of antitrust claims, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit recently affirmed a $150 million judgment in MM Steel, L.P. v. JSW Steel (USA) Inc., a hard-fought battle among steel distributors on the Texas Gulf Coast. No. 14-20267 (Nov. 25, 2015). Judge Stephen Higginson, a relatively recent Obama appointee, wrote the opinion, joined by Judges Edith Brown Clement and Fortunato “Pete” Benavides. A likely landmark in the modern law of antitrust conspiracy, the opinion unhesitatingly applies longstanding rules about “per se” antitrust liability instead of engaging in the more complex economic analysis that has dominated in recent years. By doing so, the opinion has the potential to invigorate antitrust litigation in many situations where competing businesses allegedly join forces against another competitor.

Abandoning its reputation as a skeptic of antitrust claims, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit recently affirmed a $150 million judgment in MM Steel, L.P. v. JSW Steel (USA) Inc., a hard-fought battle among steel distributors on the Texas Gulf Coast. No. 14-20267 (Nov. 25, 2015). Judge Stephen Higginson, a relatively recent Obama appointee, wrote the opinion, joined by Judges Edith Brown Clement and Fortunato “Pete” Benavides. A likely landmark in the modern law of antitrust conspiracy, the opinion unhesitatingly applies longstanding rules about “per se” antitrust liability instead of engaging in the more complex economic analysis that has dominated in recent years. By doing so, the opinion has the potential to invigorate antitrust litigation in many situations where competing businesses allegedly join forces against another competitor.

As background, the opinion notes: “In the Gulf Coast steel industry, steel manufacturers sell about half of their steel plate to end users, including companies such as Wal-Mart, Exxon, and General Motors, and sell the other half to distributors who then resell the plate to end users.” The dispute arose when two former employees of a distributor, named Chapel Steel, formed a new distribution company called MM Steel. Chapel’s management, angry at their departure and competition, not only sued MM and its founders for violation of a non-compete agreement, but began an aggressive boycott campaign to cut off MM’s supply of steel plate and put it out of business.

Evidence showed that Chapel’s leadership enlisted other distributors in its attack on MM, and also threatened several steel manufacturers, including Nucor Corporation and JSW Steel, with a boycott if they did not refuse to deal with MM. In particular, JSW received threats from Chapel and another distributor within several weeks of each other, and shortly afterwards, cancelled a supply contract that it had earlier negotiated with MM.

MM went out of business. It sued JSW for breach of contract, and sued Chapel (and other distributors), along with Nucor, JSW, and another manufacturer. After a six-week trial, the Southern District of Texas entered judgment for over $150 million for MM, finding that the distributors formed a conspiracy in violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Act to keep steel away from MM, and that the manufacturers knowingly joined that conspiracy. The distributors settled, leaving Nucor and JSW as the only appellants by the time of the Fifth Circuit’s decision.

The opinion’s analysis began by stating the accepted legal standards in the area. A Section 1 claim requires proof that the defendants “(1) engaged in a conspiracy (2) that restrained trade (3) in a particular market.” That proof must “tend[] to exclude the possibility of independent conduct,” which in a refusal-to-deal case such as this one, means showing that the defendants’ conduct is “inconsistent with the manufacturer’s independent self-interest.”

Applying these standards, the court affirmed the liability finding as to JSW. “The fact that both [distributors’ made . . . threats within several weeks of each other was sufficient evidence for a reasonable juror to conclude that JSW was aware of the horizontal conspiracy to exclude MM from the market.” Then, when JSW responded by terminating its contract with MM, virtually guaranteeing a suit for breach, “[a] reasonable juror also could have concluded that JSW’s abrupt decision to no longer deal with MM following those threats and JSW’s statements regarding that decision tended to exclude the possibility of conduct that was independent of the distributor’s conspiracy.” While JSW contended that its actions were motivated by concern about the Chapel lawsuit against MM, the court found that “[a] reasonable juror could have concluded that JSW’s explanation for its supposedly independent refusal to deal was pretextual.”

The court reversed as to Nucor, who had received only one threat, from Chapel. In response, Nucor introduced evidence that it had an “incumbency practice,” under which it remained loyal to established customers such as Chapel, to maintain a stable supply chain. The court reasoned that “[e]ven if the jury did not credit this practice, MM did not provide evidence that when Nucor first refused to quote MM, Nucor was aware of an agreement between the distributors to foreclose MM from the market. . . . In fact, at the time Nucor first refused to quote MM, Nucor believed that JSW, its competitor, was supplying MM.”

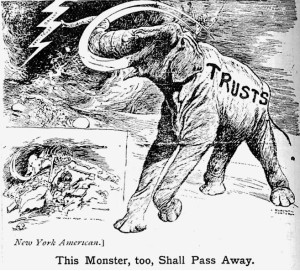

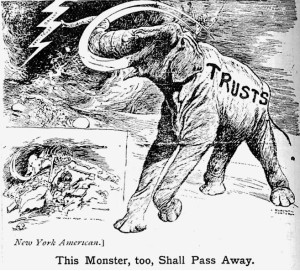

Returning to JSW, the court observed that “[t]he Supreme Court has consistently held that the per se rule [of antitrust liability] is applicable to group boycotts identical to the boycott alleged in this case.” JSW argued that in the recent opinion of Leegin Creative Leather Products v. PSKS, 551 U.S. 877 (2007) when the Supreme Court eliminated per se liability for price-setting vertical agreements (i.e, exclusive dealing arrangements), it necessarily did so for horizontal agreements such as the one among distributors in this case. The court disagreed, concluding: “Purely vertical refusals to deal . . . frequently have procompetitive justifications, such as limiting free riding and increasing specialization. However, the crux of the group boycotts at issue in the cases in which per se liability has always applied is that members of a horizontal conspiracy use vertical agreements anticompetitively to foreclose a competitor from the market.” The court concluded by rejecting a challenge to MM’s damage model.

The MM opinion has considerable significance, both practically and theoretically. Practically, a company in a position like JSW’s is not unsympathetic – on the one hand, it has substantial contract obligations to a new customer, while on the other hand, it confronts serious threats to substantial other and longstanding business. A tough business decision becomes harder when potential Section 1 antitrust liability – which carries with it the threat of treble damages – must be considered.

Theoretically, the court’s affirmation of per se liability connects to an older school of antitrust thought that emphasized bright-line rules over case-by-case analysis. That view has received strong criticism as anachronistic; as Robert Bork wrote many years ago in a famous Yale Law Journal article: “The current shibboleth of per se illegality in existing law conveys a sense of certainty, even of automaticity, which is delusive. The per se concept does not accurately describe the law relating to agreements eliminating competition as it is, as it has been, or as it ever can be.” Yet per se rules remain in place in the antitrust laws, and the MM opinion shows that they are not going away any time soon, absent sweeping action by Congress or the Supreme Court.