In Hills v. Entergy Operations, Inc., a case about overtime pay for security guards, the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment based upon a conclusion about two guards’ lack of damage. While the Court’s holding was based upon technical issues of employment law, its underlying reasoning is of broader applicability: “We reverse the district court’s summary judgment that the fluctuating workweek method applies here as a matter of law. The underlying factual issue upon which the applicabilty of that method is predicated, what the employees clearly understood, should be decided at trial in due course.” No. 16-30924 (Aug. 4, 2017). Also, in a ruling of general interest about administrative law, the Court declined to follow an interpretive letter by the Department of Labor.

In Hills v. Entergy Operations, Inc., a case about overtime pay for security guards, the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment based upon a conclusion about two guards’ lack of damage. While the Court’s holding was based upon technical issues of employment law, its underlying reasoning is of broader applicability: “We reverse the district court’s summary judgment that the fluctuating workweek method applies here as a matter of law. The underlying factual issue upon which the applicabilty of that method is predicated, what the employees clearly understood, should be decided at trial in due course.” No. 16-30924 (Aug. 4, 2017). Also, in a ruling of general interest about administrative law, the Court declined to follow an interpretive letter by the Department of Labor.

Category Archives: Administrative Law

Sun-Tzu famously counseled, “[a]ll armies prefer high ground to low and sunny places to dark.” The defendant airline in Conservation Force v. Delta Air Lines artfully changed the ground for conflict in a case about its policies toward shipments involving big game hunts. The plaintiff complained that the airlines’ policy of not accepting the shipment of lion, leopard, elephant, rhino and buffalo hunting trophies violated the airlines’ legal duty to treat all shippers equally. The Fifth Circuit agreed with the district court’s conclusion “that, despite a duty to treat all shippers equally, a common carrier does not have to treat all cargo equally.” No. 16-11062 (March 20, 2017, unpublished).

Sun-Tzu famously counseled, “[a]ll armies prefer high ground to low and sunny places to dark.” The defendant airline in Conservation Force v. Delta Air Lines artfully changed the ground for conflict in a case about its policies toward shipments involving big game hunts. The plaintiff complained that the airlines’ policy of not accepting the shipment of lion, leopard, elephant, rhino and buffalo hunting trophies violated the airlines’ legal duty to treat all shippers equally. The Fifth Circuit agreed with the district court’s conclusion “that, despite a duty to treat all shippers equally, a common carrier does not have to treat all cargo equally.” No. 16-11062 (March 20, 2017, unpublished).

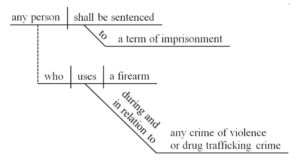

Press coverage of Judge Neil Gorsuch’s nomination to the Supreme Court has noted his intelligent and accessible writing style, including use of a sentence diagram (left) in a criminal case that turned on what elements of the crime

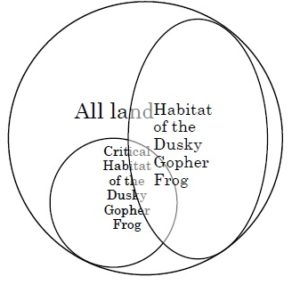

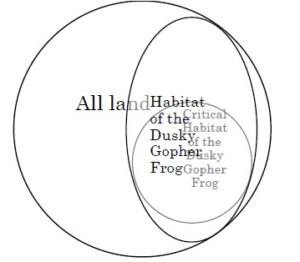

Press coverage of Judge Neil Gorsuch’s nomination to the Supreme Court has noted his intelligent and accessible writing style, including use of a sentence diagram (left) in a criminal case that turned on what elements of the crime  required proof of intent. In the same spirit, in dissent from the denial of en banc rehearing in a highly technical case about protection of the dusky gopher frog (right), Judge Edith Jones used a pair of Venn diagrams to illustrate her view of how the Endangered Species Act should operate (below left), contrasted with the panel opinion’s (below right). Markle Interests v. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, No. 14-31008 (Feb. 14, 2017).

required proof of intent. In the same spirit, in dissent from the denial of en banc rehearing in a highly technical case about protection of the dusky gopher frog (right), Judge Edith Jones used a pair of Venn diagrams to illustrate her view of how the Endangered Species Act should operate (below left), contrasted with the panel opinion’s (below right). Markle Interests v. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, No. 14-31008 (Feb. 14, 2017).

A detailed review of tax statutes and other authorities resulted in affirmance of a judgment against Bombardier related to the taxation of its “Flexjet” program; the Court summarized: “Because the law and its application to the real world is continually evolving, it is only natural that guidance in Revenue Rulings evolves too. We find a consistent theme, though, in the IRS’s guidance from the earliest Revenue Rulings grappling with this issue: where an entity is responsible for nearly every service and precondition necessary to transport persons in an aircraft, and it charges for those services, it is providing taxable transportation – even if the bona fide owner of the aircraft itself is the person traveling.” Bombardier Aerospace Corp. v. United States, No. 15-10468 (July 25, 2016).

A detailed review of tax statutes and other authorities resulted in affirmance of a judgment against Bombardier related to the taxation of its “Flexjet” program; the Court summarized: “Because the law and its application to the real world is continually evolving, it is only natural that guidance in Revenue Rulings evolves too. We find a consistent theme, though, in the IRS’s guidance from the earliest Revenue Rulings grappling with this issue: where an entity is responsible for nearly every service and precondition necessary to transport persons in an aircraft, and it charges for those services, it is providing taxable transportation – even if the bona fide owner of the aircraft itself is the person traveling.” Bombardier Aerospace Corp. v. United States, No. 15-10468 (July 25, 2016).

In an uncommon example of a successful application for an appellate stay, the Fifth Circuit stayed the EPA’s rulings about Texas’s haze reduction plans. The Court found a likelihood of success on the merits, based on, inter alia, the degree of deference required by EPA, the lack of on-point authority supporting its position, and statutory limits on its power. As to irreparable injury, the Court noted the substantial compliance costs faced by power companies (to the point of risking

In an uncommon example of a successful application for an appellate stay, the Fifth Circuit stayed the EPA’s rulings about Texas’s haze reduction plans. The Court found a likelihood of success on the merits, based on, inter alia, the degree of deference required by EPA, the lack of on-point authority supporting its position, and statutory limits on its power. As to irreparable injury, the Court noted the substantial compliance costs faced by power companies (to the point of risking  “unemployment and the permanent closure plants”), and the lack of any mechanism for them to recover those costs if the EPA’s rule was invalidated. The Court also noted “the threat of grid instability and potential brownouts,” as well as the potential injury from a violation of the federalism principles in the Clean Air Act. Finally, the court “agree[s] with Petitioners that the public’s interest in ready access to affordable electricity outweighs the inconsequential visibility differences that the federal implementation plan would achieve in the near future.” Texas v. EPA, No. 16-60118 (July 15, 2016).

“unemployment and the permanent closure plants”), and the lack of any mechanism for them to recover those costs if the EPA’s rule was invalidated. The Court also noted “the threat of grid instability and potential brownouts,” as well as the potential injury from a violation of the federalism principles in the Clean Air Act. Finally, the court “agree[s] with Petitioners that the public’s interest in ready access to affordable electricity outweighs the inconsequential visibility differences that the federal implementation plan would achieve in the near future.” Texas v. EPA, No. 16-60118 (July 15, 2016).

In a significant and technical dispute about Clean Air Act liability related to emissions at Exxon’s complex in Baytown Texas, the Fifth Circuit touched on a matter of broader interest about restitution/calculation of “benefit.” In its analysis of a proper civil penalty, the Court noted that “the effect of spending money to achieve compliance is often not mitigation of economic benefit — rather, plaintiffs may point to such expenditures as evidence of the regulated entity’s economic benefit to the extent the delay in making those expenditures allowed the regulated entity to use the money it saved productively.” Environment Texas Citizens Lobby v. ExxonMobil Corp., No. 15-20030 (May 27, 2016).

In a significant and technical dispute about Clean Air Act liability related to emissions at Exxon’s complex in Baytown Texas, the Fifth Circuit touched on a matter of broader interest about restitution/calculation of “benefit.” In its analysis of a proper civil penalty, the Court noted that “the effect of spending money to achieve compliance is often not mitigation of economic benefit — rather, plaintiffs may point to such expenditures as evidence of the regulated entity’s economic benefit to the extent the delay in making those expenditures allowed the regulated entity to use the money it saved productively.” Environment Texas Citizens Lobby v. ExxonMobil Corp., No. 15-20030 (May 27, 2016).

The Houston Professional Towing Association, a persistent if unsuccessful litigant, brought its third challenge to the City of Houston’s “SafeClear” freeway towing program. It argued that recent changes to those ordinances had changed the facts enough to remove a res judicata bar from a previous lawsuit. The Fifth Circuit disagreed, concluding that the purpose of the law remained the same (“to promote safety by expeditiously clearing stalled and wrecked vehicles”), and statistics about collisions after the program began were either indeterminate or showed that it enhanced safety. Houston Professional Towing Association v. City of Houston, No. 15-20117 (Feb. 3, 2016).

The Houston Professional Towing Association, a persistent if unsuccessful litigant, brought its third challenge to the City of Houston’s “SafeClear” freeway towing program. It argued that recent changes to those ordinances had changed the facts enough to remove a res judicata bar from a previous lawsuit. The Fifth Circuit disagreed, concluding that the purpose of the law remained the same (“to promote safety by expeditiously clearing stalled and wrecked vehicles”), and statistics about collisions after the program began were either indeterminate or showed that it enhanced safety. Houston Professional Towing Association v. City of Houston, No. 15-20117 (Feb. 3, 2016).

Dr. Barrash, a member of a professional association of neurosurgeons, testified against Dr. Oishi, who was also a group member. Dr. Oishi settled his case and filed a complaint with the association about Dr. Barrash, alleging (among other claims) that Dr. Barrash failed to review all relevant records. The association censured Dr. Barrash, who then sued the association, claiming a denial of due process and a breach of the association’s contract with its members.

Dr. Barrash, a member of a professional association of neurosurgeons, testified against Dr. Oishi, who was also a group member. Dr. Oishi settled his case and filed a complaint with the association about Dr. Barrash, alleging (among other claims) that Dr. Barrash failed to review all relevant records. The association censured Dr. Barrash, who then sued the association, claiming a denial of due process and a breach of the association’s contract with its members.

The district court found a denial of due process as to part of the censure, which the association did not appeal. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the Rule 12 dismissal of the rest of Dr. Barrash’s claims: “Dr. Barrash received sufficient due process, including notice, a hearing, and multiple levels of appeal, before he was censured for failing to review all pertinent and available records prior to testifying. Because the district court found only one basis of the censure to be unsupported by due process, the district court was correct in setting aside only that portion of the censure. Furthermore, no Texas court has recognized a breach of contract challenge to a private association’s disciplinary process.” Barrash v. American Association of Neurological Surgeons, No. 14-20764 (Feb. 3, 2016).

The district court abstained under the “primary jurisdiction” doctrine in deference to a FERC proceeding. On the threshold question of appellate jurisdiction, the Court concluded that Hines v. D’Artois, 531 F.2d 726 (5th Cir. 1976) was still good law, and allowed it to consider an otherwise-interlocutory appeal: “[T]he district court’s order resulted in Occidental being ‘effectively out of court’ and therefore functioned as a final decision.” On the merits, the Court remanded with instructions to not stay the court case indefinitely, but to instead stay for 180 days and assess the status then. Occidental Chem. Corp. v. Louisiana Public Service Comm’n, No. 15-30100 (Jan. 4, 2016).

The district court abstained under the “primary jurisdiction” doctrine in deference to a FERC proceeding. On the threshold question of appellate jurisdiction, the Court concluded that Hines v. D’Artois, 531 F.2d 726 (5th Cir. 1976) was still good law, and allowed it to consider an otherwise-interlocutory appeal: “[T]he district court’s order resulted in Occidental being ‘effectively out of court’ and therefore functioned as a final decision.” On the merits, the Court remanded with instructions to not stay the court case indefinitely, but to instead stay for 180 days and assess the status then. Occidental Chem. Corp. v. Louisiana Public Service Comm’n, No. 15-30100 (Jan. 4, 2016).

Susan Rothkamm sued for wrongful levy, after the IRS seized a CD in her name to satisfy a tax liability of her husband. The Fifth Circuit reversed the dismissal of her claim, finding that she had standing as a “taxpayer” under the broad definition of 7701 of the Internal Revenue Code: “The term ‘taxpayer’ means any person subject to any internal revenue tax.” The Court also found that limitations was tolled during the pendency of her application for a Taxpayer Assistance Order, and that the IRS did not have discretion to affect the length of that tolling period. Rothkamm v. United States, No. 14-31164 (Sept. 21, 2015). A dissent warned: “I dissent from the majority’s newly minted tolling rule. While this creativity is driven by a desire to achieve fairness, it suffers the vice common to such endeavors – it does the opposite by disrupting a carefully structured regime for the resolution of disputes between the IRS and property owners.”

The issue in United States v. CITGO was whether an “equalization tank” — a holding tank that plays a role in the process for handling oil refinery wastewater — is an “oil-water separator” within the meaning of the regulations implementing the Clean Water Act. The jury instructions quoted the regulation’s definition of an oil-water separator and then added: “[t]he definition of oil-water separator does not require that [it] have any or all of the ancillary equipment mentioned such as forebays, weirs, grit chambers, and sludge hoppers . . . . An oil-water separator is defined by how it is used.” The Fifth Circuit found an abuse of discretion in that additional sentence and reversed CITGO’s convictions: “This purely functional explanation is not what [the regulation] says, however: it defines an oil-water separator by how it is used and by its constituent parts. . . . Although the jury was also provided the exact text of Subpart QQQ, the court’s instruction told them what it means and thus undoubtedly affected the verdict. For this harmful error, the Clean Air Act convictions must be reversed.” No. 14-40128 (Sept. 4, 2015).

The issue in United States v. CITGO was whether an “equalization tank” — a holding tank that plays a role in the process for handling oil refinery wastewater — is an “oil-water separator” within the meaning of the regulations implementing the Clean Water Act. The jury instructions quoted the regulation’s definition of an oil-water separator and then added: “[t]he definition of oil-water separator does not require that [it] have any or all of the ancillary equipment mentioned such as forebays, weirs, grit chambers, and sludge hoppers . . . . An oil-water separator is defined by how it is used.” The Fifth Circuit found an abuse of discretion in that additional sentence and reversed CITGO’s convictions: “This purely functional explanation is not what [the regulation] says, however: it defines an oil-water separator by how it is used and by its constituent parts. . . . Although the jury was also provided the exact text of Subpart QQQ, the court’s instruction told them what it means and thus undoubtedly affected the verdict. For this harmful error, the Clean Air Act convictions must be reversed.” No. 14-40128 (Sept. 4, 2015).

The Department of Agriculture fined Bodie Knapp (d/b/a “The Wild Side”) $395,000 for violations of regulations about the purchase and sale of exotic animals. The Fifth Circuit largely affirmed, reviewing several basic concepts of administrative law in the process:

The Department of Agriculture fined Bodie Knapp (d/b/a “The Wild Side”) $395,000 for violations of regulations about the purchase and sale of exotic animals. The Fifth Circuit largely affirmed, reviewing several basic concepts of administrative law in the process:

- A clear regulation about a regulatory exemption trumps an arguably inconsistent summary of the regulation in an agency publication.

- Even in an environment of considerable deference, an agency ALJ must provide enough explanation so the appellate court can “reasonably discern the reason” for his ruling. Accordingly, the Court remanded for further findings as to whether “aoudad, alpaca, and miniature donkeys are ‘animals’ . . . and not ‘farm animals,'” and about the purchasers’ intentions to display “one alpaca, one auodad, two zebras, one wildebeest, two addax, seven buffalo, three nilgai, four chinchilla and one axis deer.” (No partridge in a pear tree was involved in the case.)

- It is a “heavy burden” to prove estoppel from statements made by an agency employee, and proof of a misrepresentation is only one element of that defense.

- A sale of two lemurs (as opposed to a donation) can be proven with evidence of the receipt of two zebras shortly after the delivery of the lemurs.

The opinion also affirmed on several challenges to the penalties, finding the agency’s position to not be unreasonable. Knapp v. U.S. Dep’t of Agriculture, No. 14-60002 (July 31, 2015).

Hamsher was admitted to “Timberline Knolls Residential Treatment Center” for mental health care; her employer did not pre-authorize her treatment. Unfortunately for the employer, its right under its healthcare plan to insist on precertification applied only to care in a “hospital,” and the Fifth Circuit concluded: “the administrative file contains only claim forms, none of which provide an indication as to whether Timberline is a ‘hospital’ as defined under the Plan. The name is suggestive, of course, but title alone does not constitute the type of ‘substantial evidence’ that [the employer] must put forward.” Accordingly, the Court rendered judgment for the employee, in a rare appellate reversal of an ERISA dispute.

Hamsher was admitted to “Timberline Knolls Residential Treatment Center” for mental health care; her employer did not pre-authorize her treatment. Unfortunately for the employer, its right under its healthcare plan to insist on precertification applied only to care in a “hospital,” and the Fifth Circuit concluded: “the administrative file contains only claim forms, none of which provide an indication as to whether Timberline is a ‘hospital’ as defined under the Plan. The name is suggestive, of course, but title alone does not constitute the type of ‘substantial evidence’ that [the employer] must put forward.” Accordingly, the Court rendered judgment for the employee, in a rare appellate reversal of an ERISA dispute.

In a 2-1 decision, the Fifth Circuit has denied the federal government’s request to stay the district court’s injunction against key elements of President Obama’s immigration policy. Texas v. United States, No. 15-40238 (May 26, 2015). Judge Higginson’s dissent concludes that the issues before the Court are nonjusticiable. Judge Smith’s majority (joined by Judge Elrod), made these key points:

In a 2-1 decision, the Fifth Circuit has denied the federal government’s request to stay the district court’s injunction against key elements of President Obama’s immigration policy. Texas v. United States, No. 15-40238 (May 26, 2015). Judge Higginson’s dissent concludes that the issues before the Court are nonjusticiable. Judge Smith’s majority (joined by Judge Elrod), made these key points:

- On standing — “Texas’s forced choice between incurring costs and changing its fee structure is itself an injury: A plaintiff suffers an injury even if it can avoid that injury by incurring other costs. And being pressured to change state law constitutes an injury,”‘

- On the statutory merits — “[E]ven granting ‘special deference,’ the INA provisions cited by the government for that proposition cannot reasonably be construed, at least at this early stage of the case, to confer unreviewable discretion,” and

- On the APA issue — “But a rule can be binding if it is ‘applied by the agency in a way that indicates it is binding,’ and the states offered evidence from DACA’s implementation that DAPA’s discretionary language was pretextual.”

The Fifth Circuit revised its original opinion in BNSF Railway Co. v. United States to expand and revise the discussion of ambiguity as part of the Chevron analysis of an IRS regulation; the outcome remained unchanged. No. 13-10014 (Jan. 15, 2015). The new discussion includes a reminder about the limited role of dictionaries, from the venerable en banc opinion about regulations for chicken processing in Mississippi Poultry Association, Inc. v. Madigan, 31 F.3d 293 (5th Cir.1994). The canon of “noscitur a sociis” (“an ambiguous term may be given more precise context by the neighboring words with which it is associated” also makes one of its infrequent appearances.

The Fifth Circuit revised its original opinion in BNSF Railway Co. v. United States to expand and revise the discussion of ambiguity as part of the Chevron analysis of an IRS regulation; the outcome remained unchanged. No. 13-10014 (Jan. 15, 2015). The new discussion includes a reminder about the limited role of dictionaries, from the venerable en banc opinion about regulations for chicken processing in Mississippi Poultry Association, Inc. v. Madigan, 31 F.3d 293 (5th Cir.1994). The canon of “noscitur a sociis” (“an ambiguous term may be given more precise context by the neighboring words with which it is associated” also makes one of its infrequent appearances.

The issue in Vine Street LLC v. Borg Warner Corp. was whether the defendant — a seller of dry cleaning equipment and supplies — intentionally discharged “PERC” (an unpleasant chemical widely used in dry cleaning) into the ground. No. 07-40440 (Jan. 14, 2015). While most of the opinion addresses technical matters about CERCLA , the discussion about the evidence of intent is of general interest. In particular, the Court noted testimony that the defendant’s employees handled PERC with care and did not intentionally spill it, and evidence that the defendant’s intent was to “sell useful chemicals to distributors and not to dispose of them” — in other words, “there is no evidence to suggest that [Defendant] engaged in subterfuge to disguise the disposal of PERC as a legitimate transaction surrounding the operation of a dry cleaning business.”

But all these years that I’ve been here, ain’t nobody got past Red – except Article III.

October 29, 2014“Those who prefer to hunt deer without the use of dogs (still-deer hunters) complain that

dog-deer hunting is disruptive and unsportsmanlike. Adjacent landowners complain that dog-deer hunting leads to shooting near houses and from roads, fights between dog-deer hunters and landowners, roads being blocked by dog-deer hunters, dogs running across private property, and trespass. Dog-deer hunters defend the practice based on its history as a traditional method of hunting in Louisiana dating back to the colonial period.” The plaintiffs in Louisiana Sportsmen Alliance, LLC v. Vilsack sought to enjoin the U.S. Forest Service from banning dog-deer hunting in the Kisatchie National Forest. The Forest Service won on the merits in the district court, and for the first time on appeal, argued that the plaintiff organization lacked standing. Expressing vexation: “The district court was ill-served by the Forest Service in this regard, because the Forest Service never argued that the Alliance lacked organizational standing until this appeal,” the Court nevertheless considered the issue because “Article III standing is a jurisdictional requirement that cannot be waived,” and then dismissed the appeal because the plaintiff association had not shown its standing to bring suit. No.13-31260 (Oct. 28, 2014, unpublished).

The Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board served administrative subpoenas on Transocean in connection with the Deepwater Horizon disaster. United States v. Transocean Deepwater Drilling, Inc., No. 13-20243 (Sept. 18, 2014). Transocean contended that the Board lacked jurisdiction because the ill-fated rig was not a “stationary source” within the meaning of the Board’s enabling statute; the majority disagreed, concluding that at the time of the accident, the rig “was physically connected (though not anchored) at that site and maintained a fixed position.”

Transocean also contended that this sentence deprived the Board of jurisidiction: “The Board shall not be authorized to investigate marine oil spills, which the National Transportation Safety Board is authorized to investigate.” After a foray into the grammatical thicket of “which” v. “that,” the majority concluded that the Board was not categorically barred from investigating oil spills in light of the “overall regulatory scheme.”

A dissent disagreed with both conclusions, reminded that “[f]or the sake of maintaining limited government under the rule of law, courts must be vigilant to sanction improper administrative overreach,” and noted that at least 17 other investigations were conducted into the accident.

The Public Utilities Regulatory Policies Act (“PURPA”) directs the FERC to encourage alternative energy providers, called “Qualifying Facilities” under that statute. In a novel arrangement that encourages flexibility but also can raise “troublesome” Tenth Amendment concerns, PURPA directs state agencies — such as the Texas PUC — to adopt rules that comply with FERC’s regulations and help implement PURPA. Exelon Wind 1, LLC v. Nelson, No. 12-51228 (Sept. 8, 2014) (quoting Power Resource Group v. Public Utility Comm’n of Texas, 422 F.3d 231 (5th Cir. 2005), and FERC v. Mississippi, 456 U.S. 742 (1982)).

The Public Utilities Regulatory Policies Act (“PURPA”) directs the FERC to encourage alternative energy providers, called “Qualifying Facilities” under that statute. In a novel arrangement that encourages flexibility but also can raise “troublesome” Tenth Amendment concerns, PURPA directs state agencies — such as the Texas PUC — to adopt rules that comply with FERC’s regulations and help implement PURPA. Exelon Wind 1, LLC v. Nelson, No. 12-51228 (Sept. 8, 2014) (quoting Power Resource Group v. Public Utility Comm’n of Texas, 422 F.3d 231 (5th Cir. 2005), and FERC v. Mississippi, 456 U.S. 742 (1982)).

The Texas PUC, acknowledging this mandate as well as the vagaries of wind power generation in the Texas Panhandle, enacted a rule limiting the pricing benefits of PURPA to “Qualifying Facilities able to forecast when they will deliver energy to the utility.” Exelon, a wind power producer, challenged the validity of this rule under PURPA.

The Fifth Circuit first rejected a jurisdictional challenge, finding that Exelon’s attack on the rule was an “as-applied” challenge — over which federal courts have jurisdiction – as opposed to a “facial” challenge reserved to state courts. In so reasoning, the Court declined to give Chevron deference to a “Declaratory Order” by FERC. On the merits, — again declining to give the FERC letter deference — the Court upheld the PUC regulation: “The PUC had the discretion to determine the specific parameters for ehwn a wind farm can form a Legally Enforceable Obligation, and . . . left open the possibility that other wind farms might be able to provide firm power . . . .”

A dissent, agreeing with the jurisdictional analysis, differed on the merits, finding that the PUC rule conflicts on its face with the applicable FERC regulation, and that deference was due to the “FERC’s reasonable interpretation of that regulation according to well-established principles of adminstrative deference.”

The unfortunate taxpayer in Whitehouse Hotel Limited Partnership v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue lost a multi-million dollar dispute about the value of an easement, related to the spectacular Ritz-Carlton on Canal Street in New Orleans, and as a result faced a substantial penalty. No. 13-60131 (June 11, 2014). The Fifth Circuit affirmed the Tax Court on the merits but reversed as to the penalty, noting: “We are particularly persuaded by [Taxpayer’s] argument that the Commissioner, the Commissioner’s expert, and the tax court all reached different conclusions” on the core valuation issue. Acknowledging that this area is fact-specific, the Court held as to the taxpayer’s conduct: “Obtaining a qualified appraisal, analyzing that appraisal, commissioning another appraisal, and submitting a professionally-prepared tax return is sufficient to show a good faith investigation as required by law.”

Aransas Project v. Shaw presented a challenge to an injunction against the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, prohibiting the TCEQ from issuing new permits to withdraw water from rivers that feed the estuary where whooping cranes live. No. 13-40317 (June 30, 2014). The whooping crane, described in the opinion as a “majestic bird that stands five feet tall,” is an endangered species, and the only known wild flock lives in Texas during winter.

The Fifth Circuit first rejected an argument for Burford abstention, finding that this case presented a “broader grant of administrative and judicial authority by state law to remedy environmental grievances” than a prior opinion where it allowed abstention in a similar sort of environmental dispute. Cf. Sierra Club v. City of San Antonio, 112 F.3d 789 (5th Cir. 1997).

The Court then reversed the injunction, finding no causation “in the face of multiple, natural, independent, unpredictable and interrelated forces affecting the cranes’ estuary environment.” While couched in language about proximate causation and environmental law, the Court’s analysis is a classic illustration of the recurring Daubert problem of excluding alternate causes. (In the course of this discussion, the butterfly effect theory makes a cameo appearance in footnote 10.)

A company received “PRP” (Potentially Responsible Party) letters from the EPA, followed by a “Unilateral Administrative Order” requiring the company to do remedial work. Its CGL insurer denied coverage, contending that these administrative communications under CERCLA were not a “suit” that triggered the duty to defend. McGinnes Industrial Maintenance Corp. v. Phoenix Ins. Co., No. 13-20360 (June 11, 2014, unpublished). The insured argued that the word “suit” was ambiguous and thus led to coverage; the insurer argued that a broad reading of “suit” was inconsistent with the word “claim” in the policy and the word “petition” in the usual phrasing of the Texas “eight corners” rule. Finding the issue important and that “the parties each make reasonable arguments” about it, the Fifth Circuit certified this question to the Texas Supreme Court: “Whether the EPA’s PRP letters and/or unilateral administrative order, issued pursuant to CERCLA, constitute a ‘suit’ within the meaning of the CGL policies, triggering the duty to defend.” That Court has now answered yes and the case has been remanded for further proceedings.

Burnett Ranches, Inc. operates the sprawling Four Sixes and Dixon Creek ranches in the Texas Panhandle; its history runs to Captain Samuel “Burk” Burnett’s land dealings in the 19th Century with Comanche chief Quanah Parker. The IRS contended that its current owner (Captain Burnett’s great-granddaughter) was subject to accrual rather than cash accounting pursuant to a law against “farm syndicate” tax shelters. Burnett Ranches v. United States, No. 13-10403 (May 22, 2014). The Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for the ranch as to an exception to that law for active farm operators: “To accept the government’s overly expansive reading of § 464 by crediting its overly narrow reading of the Active Participation Exception would be to sanction ‘administrative legislation’ by an Article II executive agency. This we decline to do, agreeing instead with the district court that the government’s efforts fail, grounded as they are in nothing more than the fact that legal title to Ms. Marion’s interest in Burnett Ranches stands in the name of her S corp.” Of general interest, the Court concluded that “interest” has a broad, nontechnical meaning so long as it does not have a “narrowing modifier.”

Even by the standards of tax cases, BNSF Railway Co. v. United States is arcane, but the underlying statutory analysis is of broad general interest. No. 13-10014 (March 13, 2014). The first issue — the taxability of certain stock options — turned on whether a Treasury regulation about the meaning of the term “compensation” was entitled to Chevron deference. The Fifth Circuit held that it was — as to the first Chevron factor, the Court found the term ambiguous, noting (1) the lack of a similar statute using the term, (2) variation among dictionary definitions, and (3) ambiguity in business usage, such as there was, at the time the relevant statute was passed in the 1920s-40s. [Unintentional capitalist wit appears in footnote 63, which refers to the “Rand House Dictionary” rather than the “Random House Dictionary” in a citation about “capital or finance.”] The Court then found the regulation reasonable, noting its general consistency with the goals and structure of the statute and its legislative history. A second holding illustrates the application of the “specific-general canon” and “the rule against superfluities.”

The plaintiff in Bradberry v. Jefferson County, Texas alleged that he was terminated from his job as a county corrections officer, in violation of federal law, because he was called to service in the Army Reserve during Hurricane Ike. No. 12-41040 (Oct. 17, 2013). A key issue was whether a county administrative proceeding about his termination had collateral estoppel effect on his later federal lawsuit. The Fifth Circuit, noting that administrative proceedings can create collateral estoppel if state law would allow it, held that the questions were different and no estoppel arose: “We conclude that a finding that Bradberry was discharged due to a disagreement about military service is not the equivalent of a finding that the County was motivated by his military status to discharge him.” While analogical reasoning from this fact-specific holding may pose challenges, it still provides a clearly-stated example of when issues become “identical” for purposes of issue preclusion.

The plaintiff in Asadi v. G.E. Energy (USA), LLC was terminated after making an internal report of a potential securities law violation. No. 12-20522 (July 17, 2013). The Fifth Circuit affirmed the Rule 12 dismissal of his whistleblower claim based on Dodd-Frank: “Based on our examination of the plain language and structure of the whistleblower-protection provision, we conclude that the whistleblower protection provision unambiguously requires individuals to provide information relating to a violation of the securities laws to the SEC to qualify for protection . . . . (emphasis in original)” The Court acknowledged a more expansive SEC regulation on the point, but found it was not entitled to Chevron deference given the clarity of the statute.

“The court subordinated the equities of a particular situation to the overmastering need for certainty in the transactions of commercial life.” Benjamin Cardozo, The Growth of the Law 111 (1924). In Medco Energi US, LLC v. Sea Robin Pipeline Co., the plaintiff — a natural gas producer — argued that the defendant pipeline company had misrepresented how long it would take to make repairs after Hurricane Ike. No. 12-30791 (July 2, 2013). The Fifth Circuit found this claim preempted by federal law under the “filed rate” doctrine, under which a rate filed with FERC is conclusive “[e]ven if a rate is misrepresented to a customer and the customer relies on that rate . . . .” (citing AT&T v. Central Office Telephone, 524 U.S. 214 (1988). Otherwise, “[b]ecause [plaintiff] only paid for interruptible service subject to these provisions, allowing recovery for damages incurred when it could not use [defendant’s] pipeline would conflict with the interruptible rate and the provisions of the [filed] tariff.”

In Nevada Partners Fund LLC v. United States, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the district court’s approval of several IRS rulings about investment arrangements. No. 10-60559 (June 24, 2013). The thorough opinion details a “straddle trade” investment, which in theory can generate profit, but here “as designed and carried out, [the trades] simply could not produce a profit; they were calculated and managed to produce offsetting gains and losses.” Various penalties based on the partnerships’ negligence and lack of care were also affirmed.

“The thirty-eight monks of St. Joseph Abbey,” unable to earn income from the abbey’s timberland after Hurricane Katrina, began to sell handmade funeral caskets at a price significantly lower than that offered by funeral homes. The Louisiana State Board of Embalmers and Funeral Directors contended that these sales violated state regulations, and the monks sought relief under the 14th Amendment, arguing that the regulations had no rational basis as applied to them. St. Joseph Abbey v. Castille, No. 11-30756 (rev’d Nov. 21, 2012). After an exceptionally thorough review of due process principles in the context of “rational basis review” of economic regulation (which Judge Haynes declined to join as unnecessary), the Court certified a question to the Louisiana Supreme Court about the scope of the relevant enabling statute.

Earlier this year, the Fifth Circuit largely affirmed a series of rulings about governmental immunity in litigation about flood damage from Hurricane Katrina, allowing some cases to proceed and finding the government immune as to others. On rehearing, the Court found that the “discretionary-function exemption” to the Federal Tort Claims Act created immunity even if the Flood Control Act did not. In re Katrina Canal Breaches Litigation at 25-26 (Sept. 24, 2012) (“Our construction of the FCA leaves undisturbed the district court’s ruling on that issue. Our application of the DFE, however, completely insulates the government from liability.”).

Finding that the EPA’s action was “[s]ixteen years tardy” and “without basis in the Clean Air Act or its implementing regulations,” the Court vacated an EPA rule that would have voided roughly 140 permits for various pollution-emitting businesses in Texas. State of Texas v. EPA, No. 10-60614 (Aug. 13, 2012).

Environmental groups challenged several plans approved by the Department of the Interior for oil exploration and development in the Gulf of Mexico after the Deepwater Horizon accident. In a group of consolidated cases, the Fifth Circuit dismissed the challenges on procedural grounds. See, e.g., Gulf Restoration Network v. Salazar, No. 10-60411 (May 30, 2012). Among other holdings, the Court found that the groups had standing as organizations to sue, op. at 8-10, and that case law about the effect of an agency’s allegedly “illegal [and] clandestine” internal policies did not excuse the groups’ failure to exhaust administrative remedies here. Op. at 29.

In a forcefully-written opinion, the Court vacated the EPA’s disapproval of Texas environmental emission regulations relevant to the power industry. Luminant Generation Co. v. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, No. 10-60891 (March 26, 2012). The Court found that the EPA erroneously invoked Texas law and applied federal law incorrectly. See Op. at 21 (“EPA disapproved the PCP Standard Permit . . . based on its purported nonconformity with three extra-statutory standards that the EPA created out of whole cloth”). The Court concluded: “Because the EPA waited until more than three years after the statutory deadline to act on Texas’s submission, we order the EPA to reconsider it expeditiously [on remand].” Id.

The Court affirmed almost all of a series of immunity rulings by the district court in the consolidated litigation against the Corps of Engineers arising from Hurricane Katrina. In re Katrina Canal Breaches Litigation (March 2, 2012). While most of the opinion focuses on issues unique to flood control, it provides a crisp summary of the requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act as to environmental impact statements, and concludes with a brief summary of the standards for mandamus relief in the federal system. Op. at 27. The Court declined to grant a writ of mandamus to stay an upcoming trial because its opinion affirmed the immunity rulings that the district court would use for that trial. (A subsequent opinion mooted the mandamus issue because it changed the disposition of the merits.)

In a complicated case about jurisdiction over a challenge to administrative action, the Court addressed the general effect of presumptions under the Federal Rules of Evidence and Rule 301 in particular. City of Arlington v. FCC (No. 10-60039, Jan. 23, 2012). The Court reminded that under the “bursting-bubble” approach of Rule 301, “the only effect of a presumption is to shift the burden of producing evidence with regard to the presumed fact.” Op. at 42. Accordingly, “once a party introduces rebuttal evidence sufficient to support a finding contrary to the presumted fact, the presumption evaporates,” and “[t]he burden of persuasion with respect to the ultimate question at issue remains with the party on whom it originally rested.” Id.

Buffalo Marine v. United States, an arcane Chevron case about cleanup expenses for an oil spill, reminds in discussion of a specific statutory defense under the Oil Pollution Act that: “While some contractual relationships are themselves contracts, other contractual relationships merely relate to contracts. The fact that no contract exists between two parties does not preclude the parties from having a ‘contractual’ relationship.” Op. at 7-8. This reminder may provide useful insight in litigation about insurance coverage and contract interpretation cases that involve the term “contractual relationship.”

The case of Texas Pipeline v. FERC involved a challenge to natural gas regulations as beyond FERC’s statutory authority. The Court found that the regulations were beyond that authority, and accordingly, did not reach any issues where agency deference under Chevron could be appropriate. See Op. at 5 (“[A]gencies cannot manufacture statutory ambiguity with semantics to enlarge their congressionally mandated border.”) The Fifth Circuit has taken a conservative view of agency opinions about statutory authority in other thoughtful opinions, see, e.g., Mississippi Poultry v. Madigan, 31 F.3d 293 (5th Cir. 1994) (en banc) (construing the term “same” in statute governing regulation of poultry processing).