Illustrating the choppy waters that can surround a nationwide injunction, in December, Fifth Circit judges reached three different conclusions about whether to stay the Corporate Transparency Act and related administrative rules. The motions-panel majority held:

Illustrating the choppy waters that can surround a nationwide injunction, in December, Fifth Circit judges reached three different conclusions about whether to stay the Corporate Transparency Act and related administrative rules. The motions-panel majority held:

The district court concluded that both are unconstitutional and issued nationwide injunctions against each, despite no party requesting it do so and despite every other court to have considered this issue tailoring relief to the parties before it or denying relief altogether.

The third member of the motions panel concurred in part:

[She] agrees for an expedited appeal and agrees that a national injunction is not appropriate here, so she would grant a temporary stay of the preliminary injunction pending the decision of the merits panel regarding whether to deny a stay pending appeal as to the non-parties. However, she would deny the temporary stay as to the parties (while, of course, deferring to the merits panel on this point as well), including the members of NFIB, as long as their identities are disclosed to the government.

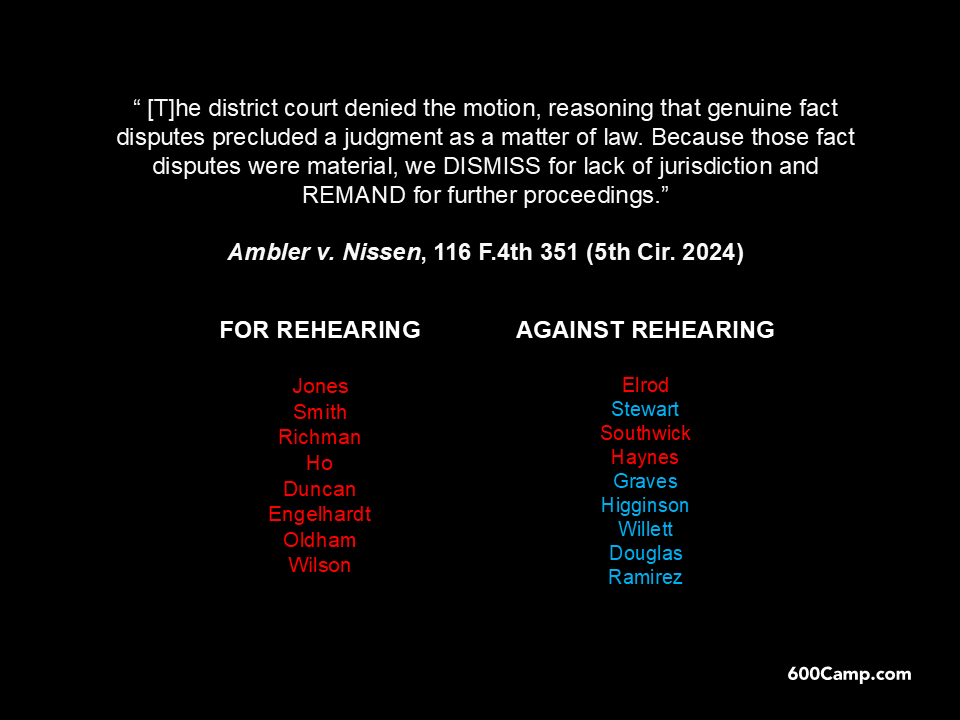

A later per curiam order, which may have issued from the merits panel, or may simply reflect communication with that panel, reached a different conclusion:

The merits panel now has the appeal, which remains expedited, and a briefing schedule will issue forthwith. However, in order to preserve the constitutional status quo while the merits panel considers the parties’ weighty substantive arguments, that part of the motions-panel order granting the Government’s motion to stay the district court’s preliminary injunction enjoining enforcement of the CTA and the Reporting Rule is VACATED.

These changes show how minor variations in panel makeup can have profound consequences when nationwide equitable relief is at issue. (The party-presentation issue referred to by the motions-panel majority is also addressed in my recent Cornell Law Review essay.)

Bruen, Rahimi, and their history-focused perspective on the Second Amendment led to a firearms restriction being held unconstitutional because:

Bruen, Rahimi, and their history-focused perspective on the Second Amendment led to a firearms restriction being held unconstitutional because: