Monthly Archives: November 2024

Cocroft v. Graham addressed the constitutionality of Mississippi’s restrictions on medical marijuana advertising. Since marijuana remains illegal under federal law, including for medical purposes, Mississippi can lawfully restrict advertising related to it. The Fifth Circuit emphasized that “the First Amendment poses no obstacle to a ban on such speech” because the underlying commercial activity is not lawful under federal law.

Cocroft v. Graham addressed the constitutionality of Mississippi’s restrictions on medical marijuana advertising. Since marijuana remains illegal under federal law, including for medical purposes, Mississippi can lawfully restrict advertising related to it. The Fifth Circuit emphasized that “the First Amendment poses no obstacle to a ban on such speech” because the underlying commercial activity is not lawful under federal law.

Specifically, the Court rejected the plaintiffs’ argument that only the sovereign enacting the underlying prohibition (in this case, the federal government) could restrict related commercial speech. The Supremacy Clause ensures federal law’s primacy, making marijuana illegal in every state, including Mississippi. Therefore, Mississippi’s restrictions on medical marijuana advertising are constitutionally permissible. No. 24-60086, Nov. 22, 2024.

Jones v. Reeves grounded the long-flying litigation about governance of the Jackson Airport, observing:

Jones v. Reeves grounded the long-flying litigation about governance of the Jackson Airport, observing:

There is also a fundamental disconnect between the Plaintiffs’ theory of employment-related injury, i.e. loss of per diem and travel reimbursement, and the remedy they seek, which is an injunction preventing abolition of the [Jackson Municipal Airport Authority]. … The elimination of JMAA and its replacement by the [Jackson Metropolitan Area Airport] Authority is the crux of this case. JMAA Commissioners’ per diem and travel expenses compensate and reimburse them only for their official duties as appointees. If the seat to which these duties are owed disappears, so too does the need for any associated reimbursement or compensation. With the elimination of the JMAA, there are no official duties requiring a per diem; and in the absence of JMAA -related travel expenses, there is nothing to reimburse.

No. 24-60371 (Nov. 19, 2024). Accordingly, the Court dismissed the case because the plaintiffs lacked individual standing, as their injuries were “institutional” and not personal.

Quoted in a recent American Prospect article, I muse that the New York AG probably won’t be headed down this way to sue the Trump Administration – link here.

Contractual ambiguity is easily the #1 issue, in commercial cases, where thoughtful judges disagree. An example appears in Barrios v. Centaur LLC, where both the district court and the Fifth Circuit concluded that a maritime contract had two conflicting “escape” (i.e., “other insurance”) clauses. The district court found ambiguity, but the Fifth Circuit applied a Louisiana rule that “when faced with two escape clauses threatening coverage, courts must find them ‘mutually repugnant’ and make both policies liable for the claim” on a pro rata basis. No. 23-30892 (Nov. 15, 2024).

Contractual ambiguity is easily the #1 issue, in commercial cases, where thoughtful judges disagree. An example appears in Barrios v. Centaur LLC, where both the district court and the Fifth Circuit concluded that a maritime contract had two conflicting “escape” (i.e., “other insurance”) clauses. The district court found ambiguity, but the Fifth Circuit applied a Louisiana rule that “when faced with two escape clauses threatening coverage, courts must find them ‘mutually repugnant’ and make both policies liable for the claim” on a pro rata basis. No. 23-30892 (Nov. 15, 2024).

Texas Tribune v. Caldwell County affirms the right of public (and with it, pres) access to pretrial bail hearings, noting, inter alia:

Public access to bail hearings helps ensure, for example, that courts act fairly and justly in setting bail.46 When courts hold private proceedings, “[t]hey can . . . avoid criticism and proceed informally and less carefully.” Allowing public access encourages adequate preparation and, in turn, precision by the court. These assurances lead to “enhance[d] public confidence in the process and result” of the justice system.

The opinion also provides a sleek example of the “citational footnote” writing style that I believe significantly enhances readability. No. 24-50135 (Nov. 15, 2024).

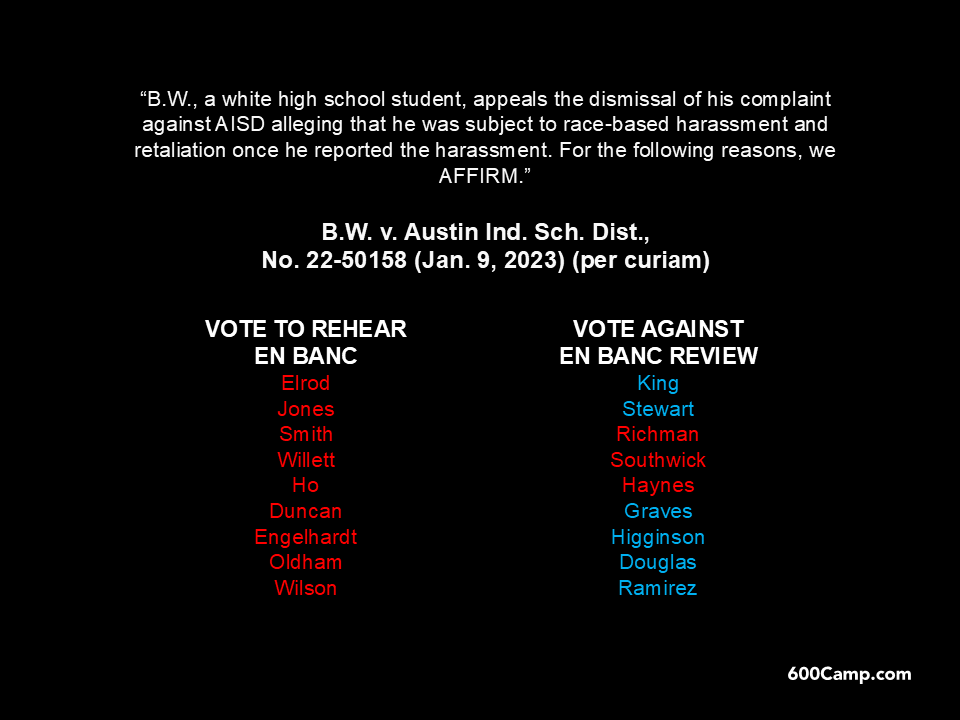

A recent en banc vote produced an unusual 9-9 tie (and thus, affirmance of the panel opinion) because a senior judge sat on the relevant panel:

The majority opinion in National Center for Public Policy Research v. SEC found that a challenge to an SEC rule about the contents of proxy ballots was not justiciable, noting, inter alia:

The majority opinion in National Center for Public Policy Research v. SEC found that a challenge to an SEC rule about the contents of proxy ballots was not justiciable, noting, inter alia:

“[C]onsider the chain of assumptions the Center’s theory requires. First, we must anticipate that third-party companies uninvolved in this litigation will choose to exclude the Center’s measure in their proxy materials. We must do so mindful that many companies have since opted to include the Center’s measure without SEC intervention.

Next, we must assume the same third-party companies will base their exclusion decision on the same grounds as Kroger and seek SEC staff advice. No matter that at least thirteen independent reasons exist for excluding proxy statements, or that the SEC staff is under no obligation to offer its advice if requested.

We must further assume that the SEC will issue the same no-action letter sent to Kroger, disregarding that staff advice is limited to each ‘particular instance.’ If SEC staff issues the letter, we must also infer that the third-party companies will ultimately follow through with their initial decision and exclude the proposal from their proxy materials.”

No. 23-60230 (Nov. 14, 2024) (emphasis added); accord FDA v. Alliance or Hippocractic Medicine, 144 S. Ct. 1540 (2024) (“The doctors have not shown that FDA’s actions likely will cause them any injury in fact. The asserted causal link is simply too speculative or too attenuated to support Article III standing.”). A dissent characterized thematter as one capable of repetition yet evading review.

Last Friday I received the inaugural “Lawyer’s Lawyer” award from the Dallas Bar Association, described by President Bill Mateja as a lawyer who “eats, breathes, and sleeps law” in comment and public thought about it. (Next to me is Courtney Marcus, filling in for Glenn West, who also received it.) Many thanks to Bill and the DBA, and to readers of this blog: longtime or new; enthusiastic or not!

Last Friday I received the inaugural “Lawyer’s Lawyer” award from the Dallas Bar Association, described by President Bill Mateja as a lawyer who “eats, breathes, and sleeps law” in comment and public thought about it. (Next to me is Courtney Marcus, filling in for Glenn West, who also received it.) Many thanks to Bill and the DBA, and to readers of this blog: longtime or new; enthusiastic or not!

Classically, judicial opinions consist of dicta and holding; the process of distinguishing the two and applying the correct rule of law in a specific case is the essence of the common-law method. A variant on that classical model sometimes arises in cases on remand from the U.S. Supreme Court, when the panel discusses that Court’s mandate; an example of which appears in the remand of NetChoice LLC v. Paxton, No. 21-51178 (Nov. 7, 2024).

The appellants in Legacy Recovery Servcs, LLC v. City of Monroe tried mightily, but was unable to persuade the Fifth Circuit that it had appellate jurisdiction over an order that partially granted and denied motions to dismiss.

The appellants argued that the ruling was an appelable collateral order. The Court saw otherwise, holding that the order did not “conclusively determine the disputed question” because it dismissed some claims while retaining others. Exercising jurisdiction over such an order risked encouraging piecemeal appeals that would require the Court to review the same intertwined claims multiple times.

Also, the issues resolved by the district court were not “completely separate from the merits of the action.” The dismissed and retained claims were based on the same statutes, and thus interwoven with the issues left before the district court.

Lastly, the Court held that the order was not “effectively unreviewable on appeal from a final judgment,” pointing out that if the appellants’ concerns were valid, the Court could vacate the judgment and order a new trial after final judgment. No. 24-30211 (Nov. 6, 2024).

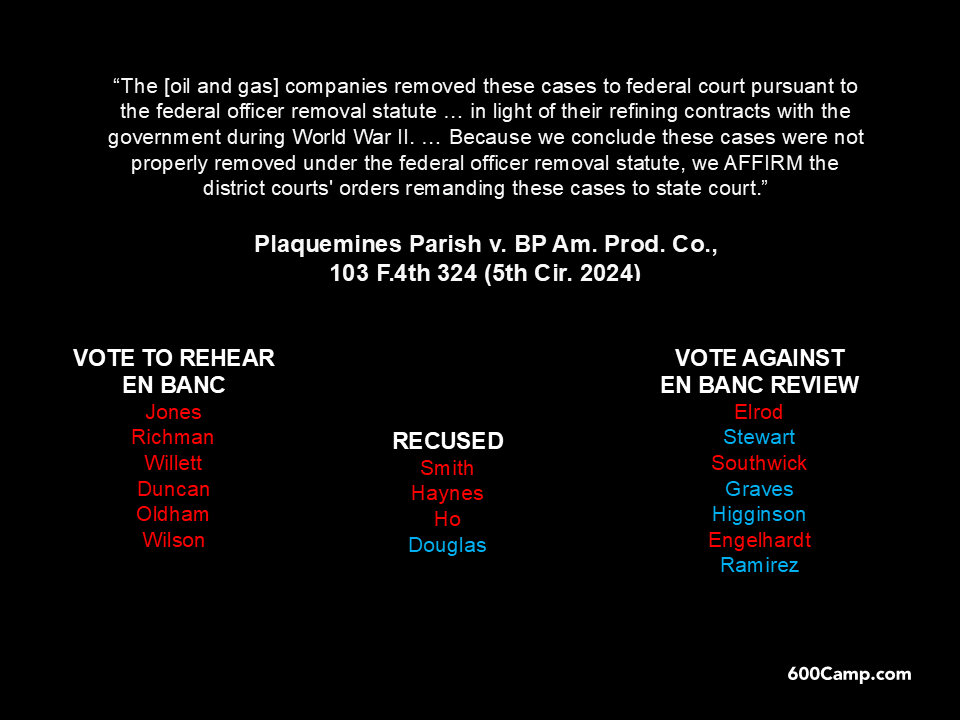

A 2-1 panel decision about an issue of federal-officer removal produced a close vote against en banc review, broken down as follows:

Even the most enthusiastic perspectives about federal-court jurisdiction have limits, as shown by Lowery v. Texas A&M Univ., a discrimination case filed by a college professor:

“Professor Lowery says that he is ‘able and ready’ to apply for lateral positions at [Texas A&M] University. But he never submitted an application to substantiate his interest. That fact is fatal in this case because there is little evidence that submitting a job application would be a futile gesture.”

No. 23-20481 (Oct. 30, 2024) (emphasis added).