The great Sherlock Holmes story The Hound of the Baskerviles took place on the English moor. The Fifth Circuit case of Diamond Services Corp. v. RLB Contracting, Inc., No. 23-40137 (Aug. 16, 2024), also involved a promlem of mooring:

The great Sherlock Holmes story The Hound of the Baskerviles took place on the English moor. The Fifth Circuit case of Diamond Services Corp. v. RLB Contracting, Inc., No. 23-40137 (Aug. 16, 2024), also involved a promlem of mooring:

Restaurant Law Center v. U.S. Dep’t of Labor presents a case study in review of an agency regulation after Loper-Bright:

Restaurant Law Center v. U.S. Dep’t of Labor presents a case study in review of an agency regulation after Loper-Bright:

“In short, as to supporting work, the Final Rule replaces the Congressionally chosen touchstone of the tip-credit analysis—the occupation—with one of DOL’s making—the timesheet.” No. 23-505762 (Aug. 23, 2024).

In Mission Pharmacal Co. v. Molecular Biologicals, Inc., the Fifth Circuit reversed the district court’s conclusion that a contract was “unambiguously silent” about certain reimbursements.

In Mission Pharmacal Co. v. Molecular Biologicals, Inc., the Fifth Circuit reversed the district court’s conclusion that a contract was “unambiguously silent” about certain reimbursements.

The case turned on the term “chargeback management.” The Court emphasized that the contract contemplated credits being issued to wholesalers, which undermined Molecular’s argument that Mission unilaterally assumed that obligation without contractual support:

“[F]aced with the question of whether the meaning of chargeback services includes reimbursement from Molecular, the fact that one answer leads to a harmonious contract, while the other leads to a dissonant one, is informative in determining the meaning of the term.”

No. 23-50321 (consolidated with No. 23-50446), August 16, 2024.

Mieco LLC v. Pioneer Natural Resources USA, Inc. involved a dispute over a natural gas supply contract affected by Winter Storm Uri.

Pioneer Natural Resources invoked the contract’s force majeure clause to excuse its failure to deliver gas during the storm. The clause defined force majeure as an “event or circumstance which prevents one party from performing its obligations,” and specified that the event must be beyond the party’s reasonable control and not due to its negligence. The clause further required the party to be “unable to overcome or avoid” the event “by the exercise of due diligence.”

The Fifth Circuit upheld the district court’s conclusion that “prevent” does not mean performance must be impossible, but can also include a significant hindrance or impediment. That said, the Court reversed summary judgment on whether Pioneer exercised the necessary “due diligence” to mitigate the storm’s effects. The clause required Pioneer to make reasonable efforts, and the Court identified factual disputes about whether Pioneer could have purchased spot market gas to fulfill its obligations, leading to a remand for further proceedings. No. 23-10575 (July 16, 2024).

In the high-profile Dallas case challenging the FTC’s new rule about noncompete enforcement, Judge Ada Brown ruled for the plaintiffs in all respects. Ryan LLC v. FTC (N.D. Tex. Aug. 20, 2024). The opinion sidesteps nagging questions about the propriety of a nationwide injunction by focusing on the plain terms of the Administrative Procedure Act:

In Canadian Standards Assoc. v. P.S. Knight Co. the Fifth Circuit resolved a copyright case about the reproduction and sale of Canadian model codes involving the Candaian electrical, propane, and oil-pipeline industries. Each of the relevant codes was fully incorporated into Canadian law in those areas.

In Canadian Standards Assoc. v. P.S. Knight Co. the Fifth Circuit resolved a copyright case about the reproduction and sale of Canadian model codes involving the Candaian electrical, propane, and oil-pipeline industries. Each of the relevant codes was fully incorporated into Canadian law in those areas.

The Court held that once these model codes were enacted into law, they lost their copyright protection under U.S. law, referencing its earlier decision in Veeck v. Southern Bldg. Code Congress, Int’l. The Court also rejected CSA’s efforts to distinguish Veeck, noting that the legal principle–incorporation into law means a loss of copyright protection–applied equally to the Canadian context. 23-50081; Aug. 15, 2024.

The Fifth Circuit addressed a range of trademark-related claims about a group of restaurants in Molzan v. Bellagreen Holdings, LLC, and reversed the grant of a Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss about them.

The Fifth Circuit addressed a range of trademark-related claims about a group of restaurants in Molzan v. Bellagreen Holdings, LLC, and reversed the grant of a Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss about them.

No. 23-20492. Aug. 12, 2024

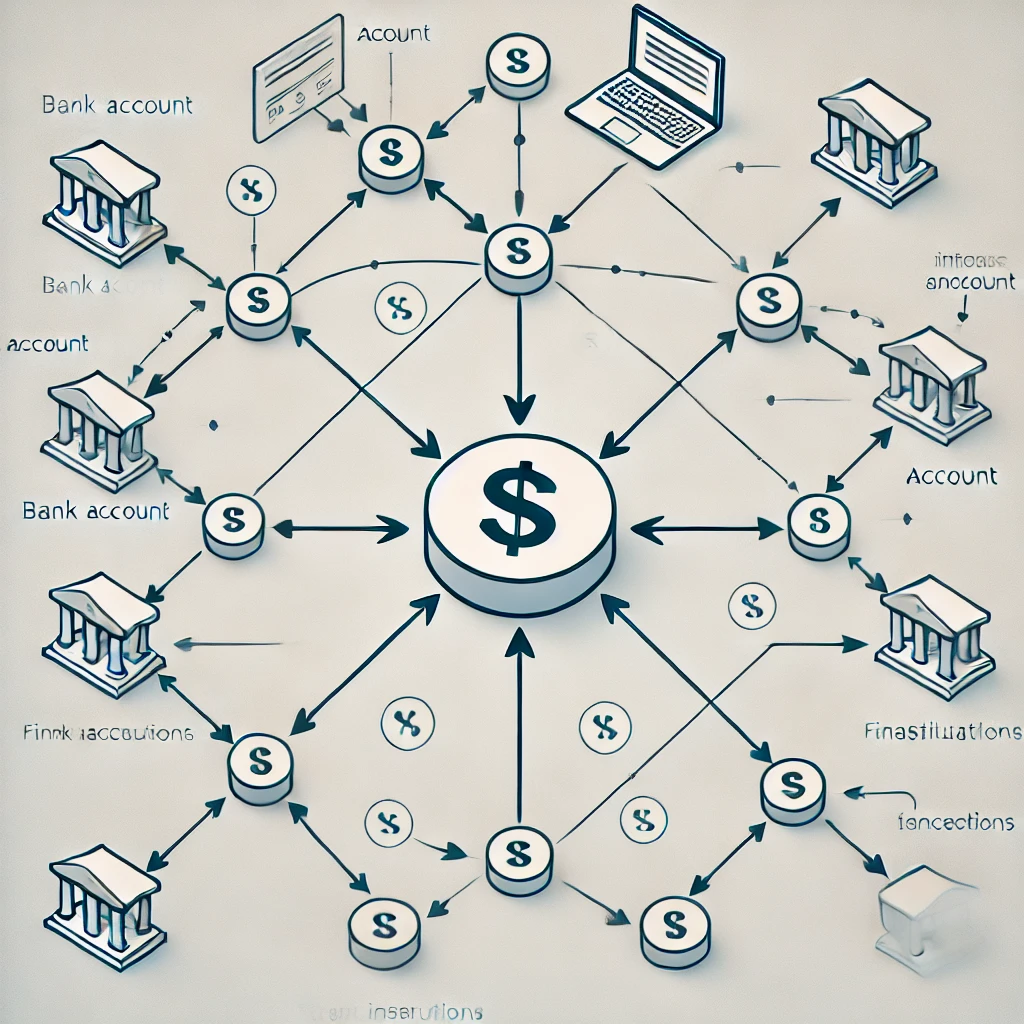

In Schmidt v. Rechnitz, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the bankruptcy court’s decision allowing a trustee to recover $10.3 million transferred to Shlomo and Tamar Rechnitz as part of a fraudulent scheme orchestrated by Mark Nordlicht, who had defrauded Black Elk Energy’s creditors.

In Schmidt v. Rechnitz, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the bankruptcy court’s decision allowing a trustee to recover $10.3 million transferred to Shlomo and Tamar Rechnitz as part of a fraudulent scheme orchestrated by Mark Nordlicht, who had defrauded Black Elk Energy’s creditors. Dickson v. Janvey clarifies the limits of a district court’s power to issue a global bar order. The Fifth Circuit held that the district court overstepped by attempting to enjoin foreign liquidators—who were not subject to its personal jurisdiction—from pursuing claims related to the Stanford Ponzi scheme in Switzerland. As the Court noted, “no in personam jurisdiction, no injunction,” rejecting the idea that a court’s in rem jurisdiction over a receivership estate could justify expansive orders against parties beyond its reach. No. 23-10726 (Aug. 15, 2024).

Dickson v. Janvey clarifies the limits of a district court’s power to issue a global bar order. The Fifth Circuit held that the district court overstepped by attempting to enjoin foreign liquidators—who were not subject to its personal jurisdiction—from pursuing claims related to the Stanford Ponzi scheme in Switzerland. As the Court noted, “no in personam jurisdiction, no injunction,” rejecting the idea that a court’s in rem jurisdiction over a receivership estate could justify expansive orders against parties beyond its reach. No. 23-10726 (Aug. 15, 2024).

The Kobayashi Maru was an impossible test used by Star Trek’s Starfleet Academy to challenge cadets. The plaintiff in Zaragoza v. Union Pacific R.R. Co. faced a similarly difficult challenge with the Ishihara test for color-blindness, leading to a dispute whether he should have been allowed to continue working as a train conductor. The Fifth Circuit held that limitations on his claim had been tolled:

The Kobayashi Maru was an impossible test used by Star Trek’s Starfleet Academy to challenge cadets. The plaintiff in Zaragoza v. Union Pacific R.R. Co. faced a similarly difficult challenge with the Ishihara test for color-blindness, leading to a dispute whether he should have been allowed to continue working as a train conductor. The Fifth Circuit held that limitations on his claim had been tolled:

“Zaragoza was included in the Harris class, as pled in February 2016 and as initially certified in February 2019. Therefore, his disability discrimination claims were tolled from the time they accrued until he asserted them, as an individual claimant, with the EEOC in March 2020.”

No. 23-50194 (Aug. 12, 2024).

Dickson v. Janvey, a dispute about the scope of an anti-litigation injunction, offers two basic reminders about the process of separating holding from dicta:

Dickson v. Janvey, a dispute about the scope of an anti-litigation injunction, offers two basic reminders about the process of separating holding from dicta:

No. 23-10726 (Aug. 9, 2024) (Enthusiasts of dicta-holding distinctions will recall that courts have discretion whether to give effect to obiter dicta–an unnecessary but thoughtful statement–under the circumstances of a particular case.)

Gibson, Inc. v. Armadillo Distribution Enterprises, Inc. presented a trademark dispute about the iconic “Flyng V” electric guitar; the appellate issue was the admissibility of evidence about third-party use before 1992–five years before the relevant party acquired the rights to the relevant marks. The Fifth Circuit held that the district court’s time limit wasn’t justified by Fed. R. Evid. 403 or the applicable trademark law, concluding that it was potentially probative as to whether the mark was “generic” and thus deserving of any protection under trademark law. No. 22-40587 (revised August 8, 2024) (applying Converse v. Int’l Trade Comm’n, 909 F.3d 1110 (Fed Cir. 2018)).

Gibson, Inc. v. Armadillo Distribution Enterprises, Inc. presented a trademark dispute about the iconic “Flyng V” electric guitar; the appellate issue was the admissibility of evidence about third-party use before 1992–five years before the relevant party acquired the rights to the relevant marks. The Fifth Circuit held that the district court’s time limit wasn’t justified by Fed. R. Evid. 403 or the applicable trademark law, concluding that it was potentially probative as to whether the mark was “generic” and thus deserving of any protection under trademark law. No. 22-40587 (revised August 8, 2024) (applying Converse v. Int’l Trade Comm’n, 909 F.3d 1110 (Fed Cir. 2018)).

The issue in Gibson, Inc. v. Armadillo Distribution Enterprises, Inc. was the admissibilty of evidence about third-party use of an alleged trademark. After concluding that the trial court erred in excluding that evidence, the Fifth Circuit considered whether the error was harmful. To illustrate that concept, the Court discussed a helpful general case on that issue, Bocanegra v. Vicmar Services, 320 F.3d 581 (5th Cir. 2003), which it summarized as follows (citations omitted):

The issue in Gibson, Inc. v. Armadillo Distribution Enterprises, Inc. was the admissibilty of evidence about third-party use of an alleged trademark. After concluding that the trial court erred in excluding that evidence, the Fifth Circuit considered whether the error was harmful. To illustrate that concept, the Court discussed a helpful general case on that issue, Bocanegra v. Vicmar Services, 320 F.3d 581 (5th Cir. 2003), which it summarized as follows (citations omitted):

In Bocanegra v. Vicmar Services, Inc., a pedestrian was fatally injured when he was struck by a streetsweeper on the median of a highway. On the eve of trial, the pedestrian’s estate sought to introduce evidence demonstrating that the driver of the streetsweeper was impaired by the use of marijuana a few hours prior to the fatal collision. Citing Rule 403 and the Daubert standard, the district court granted the driver’s motion in limine and excluded the driver’s expert testimony and an admission from the driver that he had smoked marijuana a few hours before the incident. … On appeal, this court determined that the district court’s “reliance on Rule 403 as another basis to exclude [the relevant expert] testimony concerning cognitive impairment resulting from [the driver’s] ingestion of marijuana” constituted an abuse of discretion. This court further held that the error affected the pedestrian’s substantial rights because “the jury was not presented with a complete picture of what happened on the night in question.” This court concluded that the pedestrian’s estate was left with no means of countering the driver’s argument that he “reacted reasonably and did the best he could under the circumstances.”

No. 22-40587 (Aug. 8, 2024). From there, the Court concluded that the exclusion of the third-party use evidence in the case at hand prevented the jury from getting a complete picture of the alleged trademark’s use. PREVIEW: I have an article coming out in the Texas Law Review Online this fall that uses the metaphor of a “complete picture” to analyze the past SCOTUS term’s cases about the use of history.

I take the reins in this Bloomberg article today about the U.S. Chamber of Commerce choosing to file lawsuits about administrative-agency rules in Texas / the Fifth Circuit.

A summary-judgment affidavit can clarify, but not contradict, prior testimony. In Keiland Construction LLC v. Weeks Marine Inc., the Fifth Circuit described an example of permissible clarification;

For instance, Weeks stated in its certified discovery responses that it found Keiland’s rates for its project manager and superintendent to be “excessive.” Moreover, Hafner testified that “the project manager, superintendent, and estimator are overhead people and shouldn’t be included in the [actual] cost at all.” And Hafner—at trial and in his affidavit—testified that he could not calculate the costs because of “discrepancies” in the claimed costs. So he simply hypothesized an “hourly rate . . . that [he] believed could be justified.”

Keiland fails to show how, in any of these particulars, Hafner’s affidavit “impeaches,” rather than “supplements” or “explains,” the previous testimony.

No. 23-30357 (July 25, 2024) (footnotes omitted).

Escobedo v. Ace Gathering, Inc. invovlved “Crude Haulers,” who are “drivers of large, 18-wheeled tanker trucks who drive to producers’ oil fields, load crude oil onto their trucks, and then transport that oil on public roads and highways to an ‘injection point’ on a pipeline.”

Escobedo v. Ace Gathering, Inc. invovlved “Crude Haulers,” who are “drivers of large, 18-wheeled tanker trucks who drive to producers’ oil fields, load crude oil onto their trucks, and then transport that oil on public roads and highways to an ‘injection point’ on a pipeline.”

While that activity is conducted within Texas, the pipelines carry most of the oil to customers and markets in other states. The question was whether the drivers were engaged in “interstate commerce” within the meaning of the Motor Carrier Act of 1980.

While the pathway to the present legal standard was not free from detours, the standard itself is clear–“purely intrastate transportation rises to the level of interstate commerce when the product is ultimately bound for out-of-state destinations, just as the crude oil was here,” and no evidence suggested that the oil “came to rest” at a storage facility to potentially end its interstate journey. No. 23-20494 (July 31, 2024).

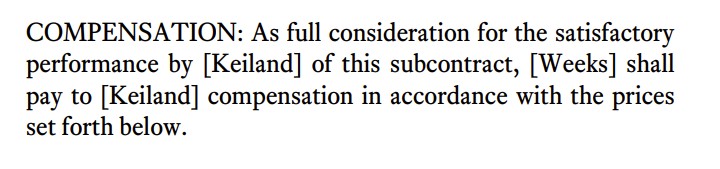

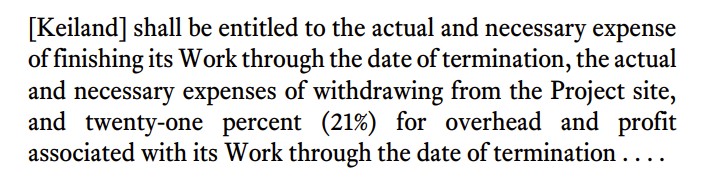

Examples of contract ambiguity don’t come along every day, so they deserve careful study when they do. Keiland Construction v. Weeks Marine found ambiguity because of tension in a contract between Section 5, titled “COMPENSATION”:

This language was followed by a schedule of lump-sum prices for various services. The other clause was Section 9, titled “TERMINATION FOR CONVENIENCE, which said in relevant part:

This language was followed by a schedule of lump-sum prices for various services. The other clause was Section 9, titled “TERMINATION FOR CONVENIENCE, which said in relevant part: The Fifth Circuit agreed with the district court that the combination of these two provisions produced ambiguity: “Keiland’s reading, that the sections required compensation for pre-termination work on a lump-sum basis and post-termination work on a cost-plus basis, is plausible. But so is Weeks’s, namely that Section 9 operated to convert all compensation due Keiland to cost-plus upon termination—particularly given that Section 9 specifies payment for 21% of costs “for overhead and profit associated with Work through the date of termination.” No. 23-30357 (July 25, 2024).

The Fifth Circuit agreed with the district court that the combination of these two provisions produced ambiguity: “Keiland’s reading, that the sections required compensation for pre-termination work on a lump-sum basis and post-termination work on a cost-plus basis, is plausible. But so is Weeks’s, namely that Section 9 operated to convert all compensation due Keiland to cost-plus upon termination—particularly given that Section 9 specifies payment for 21% of costs “for overhead and profit associated with Work through the date of termination.” No. 23-30357 (July 25, 2024).

American Warrior v. Foundation Energy Fund provides a useful reminder that “finality” can mean different things in different settings:

American Warrior v. Foundation Energy Fund provides a useful reminder that “finality” can mean different things in different settings:

AWI’s position elides the distinction between “finality” for the purposes of appealability and “finality” for the purposes of res judicata. These are related, but separate concepts. Thus, “finality for purposes of appeal is not the same as finality for purposes of preclusion.”

… Just as new facts or circumstances may warrant the modification of an injunction on behalf of a party that previously failed to obtain relief or modification, new facts or circumstances may also warrant an order modifying or lifting a bankruptcy automatic stay for a party previously denied relief. Res judicata does not tie a bankruptcy court’s hands to prevent the protection, disposition, or sale of estate property by lifting or modifying the automatic stay as changed conditions warrant.

… [P]arties may appeal the denial of a lift-stay motion, their failure to do so immediately does not prejudice their ability to obtain stay relief later, when the legal and factual landscape of the bankruptcy case changes.

No. 23-30529 (Aug. 1, 2024) (emphais removed).