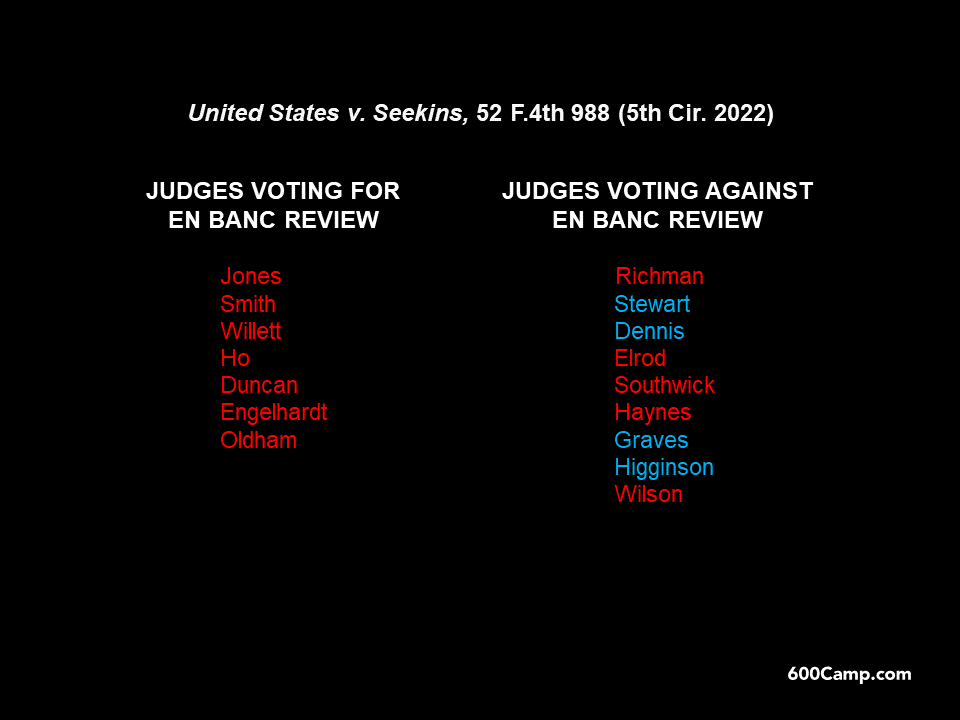

By a 9-7 vote, the Fifth Circuit declined to review en banc the panel opinion in Seekins v. United States. Under well-established Circuit precedent, Seekins presented a straightforward application of a criminal statute about possession of ammunition that had moved in interstate commerce. The petitioner directly challenged that precedent, arguing that it rested on an overly broad reading of Congress’ power to regulate interstate commerce. Plainly, the close vote signals the Court’s willingness to reconsider longstanding concepts about that constitutional provision. The breakdown of votes is below:

By a 9-7 vote, the Fifth Circuit declined to review en banc the panel opinion in Seekins v. United States. Under well-established Circuit precedent, Seekins presented a straightforward application of a criminal statute about possession of ammunition that had moved in interstate commerce. The petitioner directly challenged that precedent, arguing that it rested on an overly broad reading of Congress’ power to regulate interstate commerce. Plainly, the close vote signals the Court’s willingness to reconsider longstanding concepts about that constitutional provision. The breakdown of votes is below:

Monthly Archives: November 2022

In a straightforward application of its class-certification and Daubert case law, the Fifth Circuit rejected the certification of a class of aggrieved buyers of tickets to fly on 737 Max planes operated by Southwest Airlines, finding that the buyers suffered no cognizable injury:

[T]he plaintiffs in this suit have not plausibly alleged that they’re any worse off financially because defendants’ fraud allowed Southwest and American Airlines to keep flying the MAX 8 during the class period. If anything, plaintiffs are likely better off financially. If the MCAS defect had been widely exposed earlier, the MAX 8 flights plaintiffs chose would have been unavailable and they’d have had to take different, more expensive (or otherwise less desirable) flights instead.

The Court reasoned that if information about the MAX’s problems had become publicly known earlier than it did, then some combination of Boeing, Southwest, and the FAA would have grounded the MAX (as in fact happened), thus reducing the available supply of tickets and raising prices. Earl v. The Boeing Co., No. 21-40720 (Nov. 21, 2022).

In federal court, “the Fifth Amendment Takings Clause as applied to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment does not provide a right of action for takings claims against a state,/” but in state court, “[t]he Supreme Court of Texas recognizes takings claims under the federal and state constitutions, with differing remedies and constraints turning on the character and nature of the taking ….” Devillier v. State of Texas, No. 21-40750 (Nov. 28, 2022) (footnotes omitted).

The Fifth Circuit concluded that an effort to collect a judgment in federal court failed for lack of a sufficient amount in controversy:

… As pre-judgment interest has completely accrued during the prior case, this sum can be precisely calculated and does not vary depending on the other awards and when the plaintiff files suit. Because pre-judgment interest is an accrued component of the judgment sued upon at the time the claim to enforce the judgment arose, and because pre-judgment interest’s value does not depend on the passage of time after entry of the state court judgment, pre-judgment interest can be fairly said to constitute an ‘essential ingredient in the . . . principal claim.

As to the post-judgment interest accruing after entry of the Texas Judgment, however, we conclude that it may not be included in determining the amount in controversy in an action to enforce that Judgment. Excluding post-judgment interest from the calculation furthers § 1332(a)’s statutory purpose of preventing plaintiffs from delaying in filing suit until sufficient interest has accrued such that they can reach the jurisdictional amount.

Cleartrac LLC v. Lantrac Contractors, LLC, No. 20-30076 (Nov. 17, 2022).

The plaintiffs in National Horsemen’s Benevolent & Protective Ass’n v. Black sought to rein in the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority, a private entity created by Congress in 2020 – nominally under FTC oversight – to nationalize the regulation of thoroughbred horseracing. The Fifth Circuit scratched HISA, finding it facially unconstitutional as an excessive private delegation of federal-government power:

The plaintiffs in National Horsemen’s Benevolent & Protective Ass’n v. Black sought to rein in the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority, a private entity created by Congress in 2020 – nominally under FTC oversight – to nationalize the regulation of thoroughbred horseracing. The Fifth Circuit scratched HISA, finding it facially unconstitutional as an excessive private delegation of federal-government power:

A cardinal constitutional principle is that federal power can be wielded only by the federal government. Private entities may do so only if they are subordinate to an agency. But the Authority is not subordinate to the FTC. The reverse is true. … HISA restricts FTC review of the Authority’s proposed rules. If those rules are “consistent” with HISA’s broad principles, the FTC must approve them. And even if it finds inconsistency, the FTC can only suggest changes. … An agency does not have meaningful oversight if it does not write the rules, cannot change them, and cannot second-guess their substance.

No. 22-10387 (Nov. 18, 2022) (citations omitted, emphasis added).

For those who had doubts about the matter, Foley Bey v. Prator confirms that the search of a fez is protected by qualified immunity if conducted as part of courthouse security, notwithstanding the plaintiffs’ appeal to the U.S.-Morocco Friendship Treaty of 1836. (The digital image to the right could be called a hi-res fez.) No. 21-30489 (Nov. 17, 2022).

For those who had doubts about the matter, Foley Bey v. Prator confirms that the search of a fez is protected by qualified immunity if conducted as part of courthouse security, notwithstanding the plaintiffs’ appeal to the U.S.-Morocco Friendship Treaty of 1836. (The digital image to the right could be called a hi-res fez.) No. 21-30489 (Nov. 17, 2022).

With #RIPTwitter trending as the top hashtag on that platform, it seemed like a good time to reflect on the phenomenon that is/was #appellatetwitter, and recall the remarkable talent of now-Judge @JusticeWillett for legal tweeting:

With #RIPTwitter trending as the top hashtag on that platform, it seemed like a good time to reflect on the phenomenon that is/was #appellatetwitter, and recall the remarkable talent of now-Judge @JusticeWillett for legal tweeting:

“Foreseeability is a fundamental prerequisite to the recovery of consequential damages for breach of contract.” T & C Devine, Ltd. v. Stericycle, Inc., No. 21-20310 (Nov. 15, 2022) (citation omitted); see also Hadley v. Baxendale, [1854] EWHC J70.

“Foreseeability is a fundamental prerequisite to the recovery of consequential damages for breach of contract.” T & C Devine, Ltd. v. Stericycle, Inc., No. 21-20310 (Nov. 15, 2022) (citation omitted); see also Hadley v. Baxendale, [1854] EWHC J70.

Consistent with that principle, the Fifth Circuit affirmed a summary judgment on a consequential-damage claim when the parties’ contract said that “[a]ll information obtained by [Plaintiff] in any Annual Report . . . shall be retained in the highest degree of confidentiality,” and went on to say: “Neither party may disclose the other party’s Confidential Information to any third party without the other party’s prior written approval.”

Thus: “Devine’s damages were not a probable consequence of the breach from Stericycle’s perspective at the time of contracting because it was not foreseeable that failing to provide confidential cost and expense data would deprive Devine of the opportunity to share that information with potential licensees.”

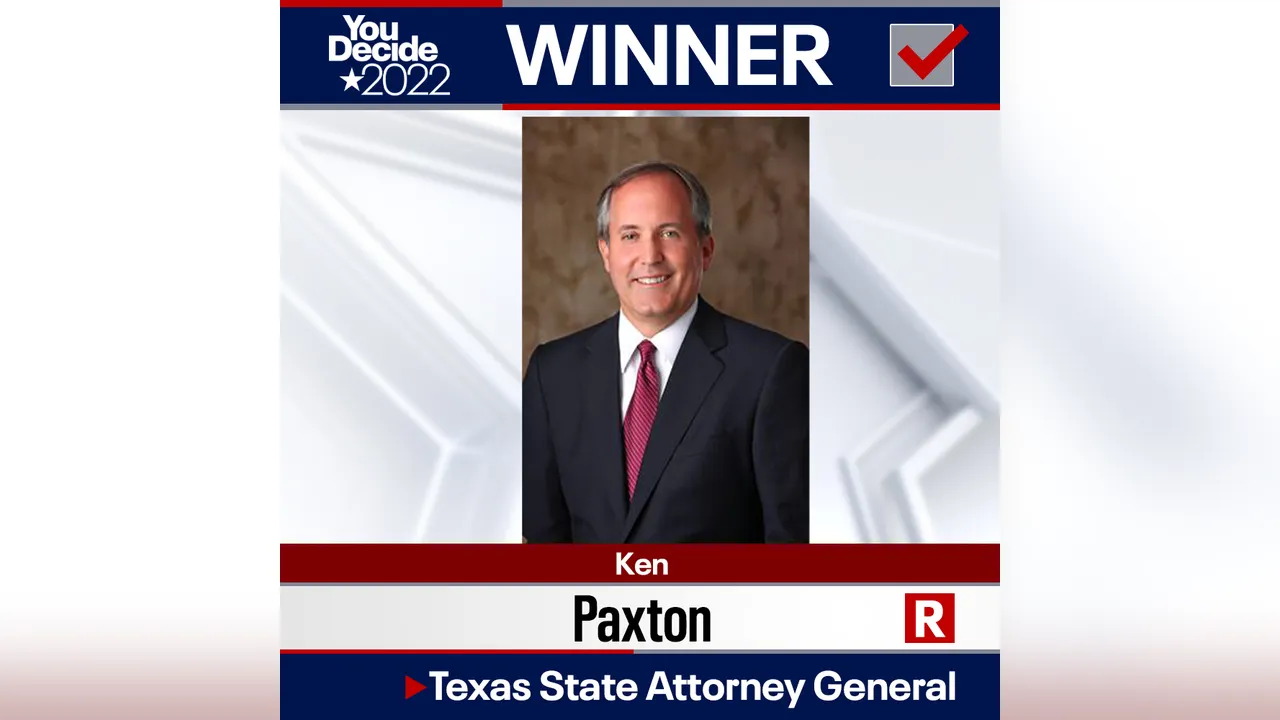

The Fifth Circuit granted mandamus relief as to an effort to subpoena Texas AG Ken Paxton for a deposition in a case about potentially overzealous enforcement of now-constitutional antiabortion laws.

The Fifth Circuit granted mandamus relief as to an effort to subpoena Texas AG Ken Paxton for a deposition in a case about potentially overzealous enforcement of now-constitutional antiabortion laws.

The panel majority concluded: (1) that the district court lacked subject matter jurisdiction and thus could not require his testimony, citing a recent Circuit case involving discovery and qualified immunity; (2) that the subpoena sought an inappropriate “apex” deposition; and (3) that plaintiffs overreached by opposing mandamus relief (because of a potential remedy by appeal), while also seeking to dismiss Paxton’s interlocutory appeal on immunity grounds (thus, extinguishing same).

A concurrence would have focused on the apex issue and not the broader dispute about jurisdiction, at least at this stage of the proceedings. In re Paxton, No. 22-50882 (Nov. 14, 2022) — REVISED, (Feb. 14, 2023).

Stringer v. Remington Arms, No. 18-60590 (Nov, 7, 2022), presents an instructive analysis of failure-to-disclose allegations, in the context of alleged fraudulent nondisclosure of a design defect in a popular rifle design.

The panel majority found a failure to satisfy Rule 9(b):

“In [plaintiffs’] complaint, they explain that they have found public resources that contradict Remington’s public statements regarding the safety of the XMP trigger. They also allege that Remington had “actual and/or physical knowledge of manufacturing, and/or, design deficiencies in the XMP Fire Control years before the death of Justin Stringer” and that the company received customer complaints regarding trigger malfunctions as early as 2008. But Plaintiffs do not make the leap to fraudulent concealment. They say merely that Remington “ignored” notice of a safety related problem.“

(applying Tuchman v. DSC Commc’ns Corp., 14 F.3d 1061, 1068 (5th Cir. 1994) (“If the facts pleaded in a complaint are peculiarly within the opposing party’s knowledge, fraud pleadings may be based on information and belief. However, this luxury ‘must not be mistaken for license to base claims of fraud on speculation and conclusory allegations.'”).

The dissent would have found that rule satisfied, based in part of the detail provided about what Remington knew: “The complaint’s allegations indicate that Remington knew about problems with the X-Mark Pro trigger before the recall but did not disclose its knowledge of those problems during the limitations period. And, contrary to Defendants’ assertion that the complaint allegations relate only to the “Walker” trigger, the deposition testimony cited in the complaint expressly references the “XMP” trigger at issue here.”

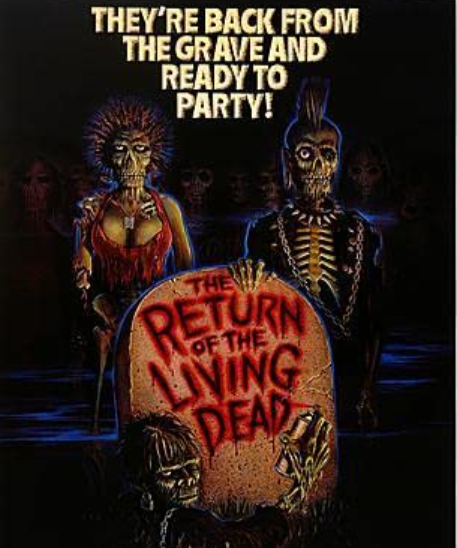

In the 1985 classic, “Return of the Living Dead,” a rainstorm spreads a zombie-creating chemical throughout a city. In 2022, the Supreme Court’s relentless focus on originalism in cases like Dobbs has also awakened long-dead legal doctrines (even as it put to bed the prospects for a “Red Wave” in 2022’s Congressional elections).

In the 1985 classic, “Return of the Living Dead,” a rainstorm spreads a zombie-creating chemical throughout a city. In 2022, the Supreme Court’s relentless focus on originalism in cases like Dobbs has also awakened long-dead legal doctrines (even as it put to bed the prospects for a “Red Wave” in 2022’s Congressional elections).

Such a resurrection can be seen in the concurrence from Golden Glow Tanning Salon v. City of Columbus, No. 21-60898 (Nov. 8, 2022), which advocates an examination of a “right to earn a living” in light of how such economic matters were understood in the late 1700s.

Of course, that phrasing is precisely how the Supreme Court described the issue in Lochner v. New York, the long-discredited 1905 opinion that struck down a maximum-hour restriction in the baking industry:

“Statutes of the nature of that under review, limiting the

hours in which grown and intelligent men may labor to earn their living, are mere meddlesome interferences with the rights of the individual ….”

The Supreme Court abandoned Lochner in the 1930s when laissez-faire ideas proved useless in the face of a systemic failure of capitalism itself. There is, of course, ample room for argument about the proper role of government in the economy. But the invocation of “originalism” to simply ignore Lochner ‘s failure is not consistent with the recognized best practices for battling zombies.

The slippery statutory-interpretation question in United States v. Palomares, briefly summarized in Monday’s post, presented a concurrence by Judge Andy Oldham. In it, he reminded of the importance of “textualism” in statutory interpretation, while cautioning against “hyper-literalism”:

The slippery statutory-interpretation question in United States v. Palomares, briefly summarized in Monday’s post, presented a concurrence by Judge Andy Oldham. In it, he reminded of the importance of “textualism” in statutory interpretation, while cautioning against “hyper-literalism”:

“‘[W]ords are given meaning by their context, and context includes the purpose of the text.’ As Justice Scalia once quipped, without context, we could not tell whether the word draft meant a bank note or a breeze. Such nuance is lost on the hyper-literalist.”

(citations omitted). He further observed:

“[H]yper-literalism … opens textualism to the very criticism that necessitated textualism in the first place. In one of the most influential law review articles ever written, Karl Llewellyn denigrated the late nineteenth century ‘Formal Period,’ in which ‘statutes tended to be limited or even eviscerated by wooden and literal reading, in a sort of long-drawn battle between a balky, stiff-necked, wrongheaded court and a legislature which had only words with which to drive that court.'”

(emphasis added, quoting Karl M. Llewellyn, “Remarks on the Theory of Appellate Decision and the Rules or Canons about How Statutes Are to Be Construed,” 3 Vanderbilt L. Rev. 395 (1950)).

The prefix “hyper-” is well chosen; Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulations developed the concept of “hyperreality,” by which “simulacra” of reality can supplant reality itself–precisely the scenario described by Llewellyn and Judge Oldham’s concurrence:

The prefix “hyper-” is well chosen; Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulations developed the concept of “hyperreality,” by which “simulacra” of reality can supplant reality itself–precisely the scenario described by Llewellyn and Judge Oldham’s concurrence:

If we were able to take as the finest allegory of simulation the Borges tale where the cartographers of the Empire draw up a map so detailed that it ends up exactly covering the territory (but where, with the decline of the Empire this map becomes frayed and finally ruined, a few shreds still discernible in the deserts – the metaphysical beauty of this ruined abstraction, bearing witness to an imperial pride and rotting like a carcass, returning to the substance of the soil, rather as an aging double ends up being confused with the real thing), this fable would then have come full circle for us, and now has nothing but the discrete charm of second-order simulacra.

Bloomberg Law provides a good summary of yesterday’s arguments in SEC v. Cochran, addressed by the en banc Fifth Circuit in 2021, as to the appropriate places to advance constitutional challenges to SEC enforcement actions.

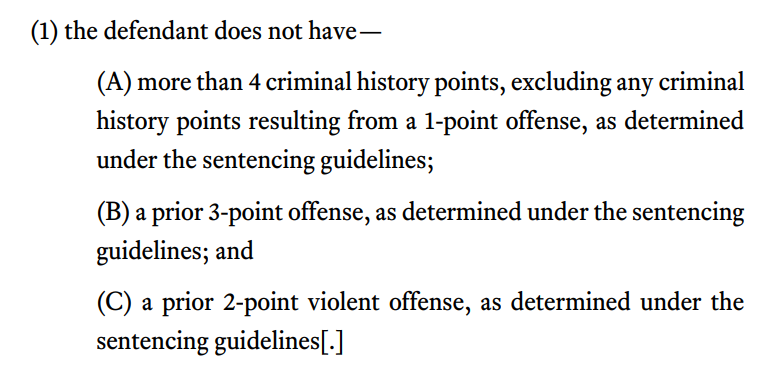

Nonami Palomares received a 120-month, mandatory-minimum sentence for smuggling heroin. She sought a lower sentence under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f), which allows a drug offender with a sufficiently minor criminal history to receive relief from a mandatory minimums if certain criteria are satisfied.

Nonami Palomares received a 120-month, mandatory-minimum sentence for smuggling heroin. She sought a lower sentence under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f), which allows a drug offender with a sufficiently minor criminal history to receive relief from a mandatory minimums if certain criteria are satisfied.

So far, simple enough. That statute, however, is extremely difficult to read. It has produced a circuit split, as well as three separate opinions from the panel members in United States v. Palomares, No. 21-40247 (Nov. 2, 2022).

Try your hand, if you dare, at reading the below law, and then compare your conclusion to the panel members’. To obtain sentencing relief, did Palomares have to negate all three matters in (A)-(C), or only one of them?

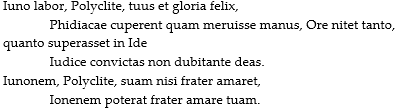

The recent en banc vote in Wearry v. Foster featured discussion of a “dubitante” opinion filed by a panel member. Unfamiliar with the term, I learned from Wikipedia that this phrase has a long and distinguished – if somewhat obscure – history in judicial opinions as a way for a judge to note his or her doubts about the rule of decision.

I then consulted my friend Brent McGuire, the pastor of Our Redeemer Lutheran Church in Dallas, who gave me further detail:

“Dubitante would literally mean ‘having doubts’ or “with a wavering [mind].’ It’s the singular participial form of the verb dubitō, dubitāre, which means to doubt or to waver. But that ‘e’ ending means it’s the ablative case, which is basically the adverbial case, that is to say, the case the noun or adjective takes when used to describe in some way a verb, adjective, or other adverb.”

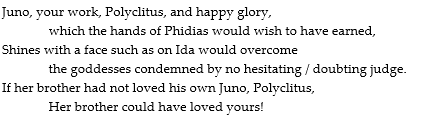

To illustrate its historical use, Pastor Maguire offered this epigram from Martial, found on the Tufts classical search engine:

which he translates roughly as:

Pastor Maguire explains: “Martial is telling the sculptor Polyclitus that his statute of Juno is so beautiful that Paris (at that most fateful beauty pageant on Ida) would have picked it over Venus (Aphrodite) and Minerva (Athena) without hesitation. Moreover, if Jupiter had not already fallen for his actual sister Juno, he would have fallen in love for Polyclitus’s statue of her.” Conversely, then, a “dubitante” judge may have joined Paris’s conclusion, but with nagging doubts about the eternal beauty of the goddesses.

The Fifth Circuit denied mandamus relief in In re Planned Parenthood, noting, in particular, that:

The Fifth Circuit denied mandamus relief in In re Planned Parenthood, noting, in particular, that:

The district court also stressed the lateness of Petitioners’ motion to transfer. It concluded that the motion was “inexcusably delayed,” observing that Petitioners “filed their motion seven months after this case was unsealed and months into the discovery period.” The district court was within its discretion to conclude that Petitioners’ failure to seek relief until late in the litigation weighed against transfer. This conclusion is only strengthened by the fact that Petitioners waited to seek transfer until after the district court denied their motion to dismiss and motion for reconsideration.

No. 22-11009 (Oct. 31, 2022) (citations omitted). In a part of the opinion joined by two judges, the Court also favorably reviewed the district court’s analysis of the underlying forum-transfer issue.