Monthly Archives: August 2019

Double Eagle Energy Services filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection and then sued two defendants for breach of contract in federal district court. Double Eagle then assigned that claim to one of its creditors; the defendants argued that this assignment destroyed federal subject matter jurisdiction. The Fifth Circuit disagreed, relying upon the “time-of-filing” rule to find that the “related to bankruptcy” jurisdiction existing when the case was filed continued to exist after the assignment. The separate question–whether the district court should nevertheless its exercise discretion to dismiss the case–was remanded, as the Court’s “ordinary practice for discretionary decisions is remanding to ‘allow the district court to exercise its discretion in the first instance.'” Double Eagle Energy Services v. Markwest Utica EMG, No. 19-30207 (Aug. 26, 2019).

Double Eagle Energy Services filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection and then sued two defendants for breach of contract in federal district court. Double Eagle then assigned that claim to one of its creditors; the defendants argued that this assignment destroyed federal subject matter jurisdiction. The Fifth Circuit disagreed, relying upon the “time-of-filing” rule to find that the “related to bankruptcy” jurisdiction existing when the case was filed continued to exist after the assignment. The separate question–whether the district court should nevertheless its exercise discretion to dismiss the case–was remanded, as the Court’s “ordinary practice for discretionary decisions is remanding to ‘allow the district court to exercise its discretion in the first instance.'” Double Eagle Energy Services v. Markwest Utica EMG, No. 19-30207 (Aug. 26, 2019).

A vocational school (RRCC) sought to recover damages from the federal government’s civil forfeiture of $4 million from it, arguing that the seizure without notice put it out of business. the Fifth Circuit found the school’s claims barred by sovereign immunity: “Congress has provided various remedies for claimants like RRCC who assert that the United States has wrongfully seized their property in forfeiture proceedings. Under certain circumstances, claimants who “substantially prevail[ ]” in a forfeiture action may recover attorneys’ fees, costs, and interest. In some cases, they may sue the United States for property damages under the FTCA. .What claimants may not do, however, is sue the United States for constitutional torts arising out of the property seizure. Congress has not waived the United States’ sovereign immunity for damages claims of that nature. Because RRCC’s counterclaims sought precisely those kinds of damages, we hold its counterclaims are barred by sovereign immunity.” United States v. $4,480,466.16, No. 18-10801 (Aug. 22, 2019), withdrawn and revised (Nov. 5, 2019).

A vocational school (RRCC) sought to recover damages from the federal government’s civil forfeiture of $4 million from it, arguing that the seizure without notice put it out of business. the Fifth Circuit found the school’s claims barred by sovereign immunity: “Congress has provided various remedies for claimants like RRCC who assert that the United States has wrongfully seized their property in forfeiture proceedings. Under certain circumstances, claimants who “substantially prevail[ ]” in a forfeiture action may recover attorneys’ fees, costs, and interest. In some cases, they may sue the United States for property damages under the FTCA. .What claimants may not do, however, is sue the United States for constitutional torts arising out of the property seizure. Congress has not waived the United States’ sovereign immunity for damages claims of that nature. Because RRCC’s counterclaims sought precisely those kinds of damages, we hold its counterclaims are barred by sovereign immunity.” United States v. $4,480,466.16, No. 18-10801 (Aug. 22, 2019), withdrawn and revised (Nov. 5, 2019).

The Fifth Circuit confirmed a district judge’s broad discretion over discovery in JP Morgan Chase Bank v. Datatreasury, a dispute about the scope of postjudgment discovery in a licensing dispute won by Chase. The Court held that the district court did not abuse its discretion in:

The Fifth Circuit confirmed a district judge’s broad discretion over discovery in JP Morgan Chase Bank v. Datatreasury, a dispute about the scope of postjudgment discovery in a licensing dispute won by Chase. The Court held that the district court did not abuse its discretion in:

- Setting a time period for relevant information, considering the scope of the judgment and the pertinent licensing agreement;

- Focusing the relevant information by reference to the judgment itself rather than the broader definition of a “creditor” under the fraudulent-transfer statutes; and

- Evaluating the “proportionality” of the requested information in light of the expense associated with older records.

No. 18-40043 (Aug. 23, 2019).

Nearly a century ago, the unfortunate Helen Palsgraf was injured in a Long Island Railroad station; the difficult tort-law issues arising from her injury continue to challenge the courts today. Martinez v. Walgreens Co. presented the question “whether, under Texas law, a pharmacy owes a duty of care to third parties injured on the road by a customer who was negligently given someone else’s prescription.” The Fifth Circuit answered “no,” considering, inter alia: (1) “[I]t was not sufficiently foreseeable that a pharmacy customer would take the medication in a bottle intended for someone else, notwithstanding that the label listed someone else’s name and a different medication,” and (2) “[T]he Texas legislature has shown itself to be both willing and able to undertake the public policy balancing inherent in extensive regulation of pharmacies’ treatment of prescription drugs.” No. 18-40636 (Aug. 6, 2019).

Nearly a century ago, the unfortunate Helen Palsgraf was injured in a Long Island Railroad station; the difficult tort-law issues arising from her injury continue to challenge the courts today. Martinez v. Walgreens Co. presented the question “whether, under Texas law, a pharmacy owes a duty of care to third parties injured on the road by a customer who was negligently given someone else’s prescription.” The Fifth Circuit answered “no,” considering, inter alia: (1) “[I]t was not sufficiently foreseeable that a pharmacy customer would take the medication in a bottle intended for someone else, notwithstanding that the label listed someone else’s name and a different medication,” and (2) “[T]he Texas legislature has shown itself to be both willing and able to undertake the public policy balancing inherent in extensive regulation of pharmacies’ treatment of prescription drugs.” No. 18-40636 (Aug. 6, 2019).

“Resolving an issue that has brewed for several years in this circuit, we conclude that the TCPA does not apply in diversity cases.” Klocke v. Watson, No. 17-11320 (revised Aug. 29, 2019) (emphasis added). “Because the TCPA imposes evidentiary weighing requirements not found in the Federal Rules, and operates largely without pre-decisional discovery, it conflicts with those rules.”

Assuming the confirmation of Hon. Sul Ozerden of Mississippi, all active-judge positions on the Fifth Circuit will soon be filled. Of the 17 judges, 12 will have been appointed by Republican Presidents (6 by President Trump), and 5 by Democrats. 8 of the 17 judges will have previously served, for some amount of time, as a state or federal trial judge.

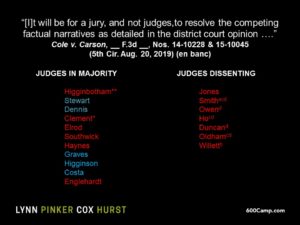

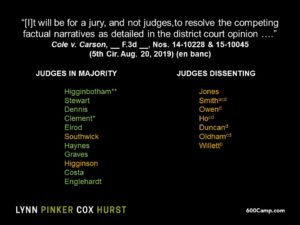

En banc votes by the Court, examined with an eye on the political party of the appointing Presidents, can show patterns. For example, in this week’s Cole v. Carson case, the Democrat-appointed judges voted the same way while the Republican-appointed judges divided. (If these slides are hard to read on your browser, clicking on them should bring them to full size and clear resolution):

All former trial judges voted the same way:

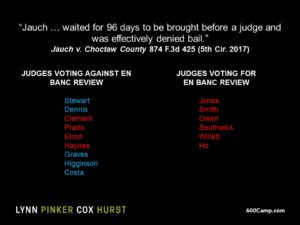

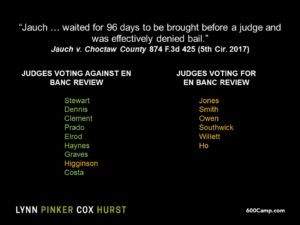

Similarly, in the 2017 case of Jauch v. Choctaw County about pretrial detention, all the Court’s Democrat-appointed judges voted against en banc review, while the Republican-appointed ones divided:

And again, all of the Court’s former trial judges voted the same way:

There are many ways to define, characterize, and otherwise describe judges and their philosophies. This quick review suggests that an exclusive focus on political-party association is too narrow.

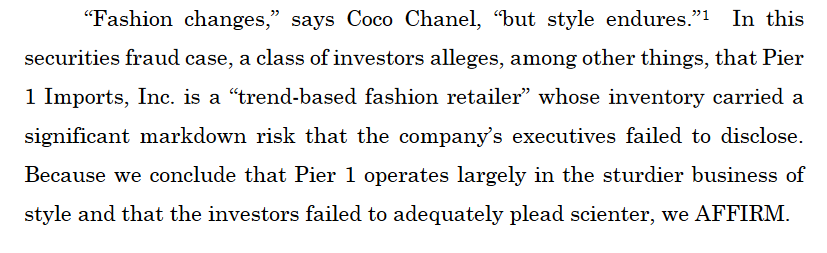

The Fifth Circuit’s published opinions this week include Municipal Employees’ Retirement System v. Pier One Imports, a large securities case involving the beleaguered stock of the “Pier One” retail chain; the second, Cole v. Carson, is a long-running, hard-fought lawsuit about a police shooting. (The fracturing of the en banc court in Cole will be the subject of an upcoming post.) Despite the gravity of these issues, the Court crafted two wonderful turns of phrase, deserving of a moment’s recognition because they are both fun and effective.

The Fifth Circuit’s published opinions this week include Municipal Employees’ Retirement System v. Pier One Imports, a large securities case involving the beleaguered stock of the “Pier One” retail chain; the second, Cole v. Carson, is a long-running, hard-fought lawsuit about a police shooting. (The fracturing of the en banc court in Cole will be the subject of an upcoming post.) Despite the gravity of these issues, the Court crafted two wonderful turns of phrase, deserving of a moment’s recognition because they are both fun and effective.

- The business question giving rise to Pier One was whether management had made wise decisions about what products to emphasize; thus, Judge Elrod began the opinion with some wise words from Coco Chanel:

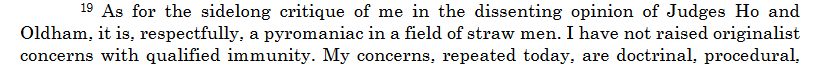

- The dissents in Cole clashed with one another as well as the majority, leading to a “fiery” retort by Judge Willett:

Texas liquor law prohibits a public corporation from holding a “P permit,” which “authorize[s] the sale of liquor, wine, and ale for off-premises consumption.” Wal-Mart successfully challenged this law as a violation of the dormant Commerce Clause.The Fifth Circuit reversed and remanded, making these observations, of general interest beyond this specific dispute, on the issue of legislative intent:

Texas liquor law prohibits a public corporation from holding a “P permit,” which “authorize[s] the sale of liquor, wine, and ale for off-premises consumption.” Wal-Mart successfully challenged this law as a violation of the dormant Commerce Clause.The Fifth Circuit reversed and remanded, making these observations, of general interest beyond this specific dispute, on the issue of legislative intent:

- “Under the law of the Fifth Circuit, evidence that legislators intended to ban potential permittees based on company form alone is insufficient to meet the purpose element of a dormant Commerce Clause claim”;

- “An admission that the drafter sought to create a law that would survive a constitutional challenge is not evidence of a discriminatory legislative purpose”;

- “[O]verreliance on ‘post-enactment testimony’ from actual legislatures is problematic, and not ‘the best indicia of the Texas Legislature’s intent'”; and

- “The motivations and lobbying efforts of the [Texas Package Store are not direct evidence of legislative purpose.”

Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission, No. 18-50299 (Aug. 15, 2019).

A long-litigated dispute about arbitrability reached its latest stage in Archer & White Sales, Inc. v. Henry Schein, Inc., on remand from the Supreme Court, in which the Fifth Circuit held: “The most natural reading of the arbitration clause at issue here states that any dispute, except actions seeking injunctive relief, shall be resolved in arbitration in accordance with the AAA rules. The plain language incorporates the AAA rules—and therefore delegates arbitrability—for all disputes except those under the carve-out. Given that carve-out, we cannot say that the Dealer Agreement evinces a ‘clear and unmistakable’ intent to delegate arbitrability.”

A long-litigated dispute about arbitrability reached its latest stage in Archer & White Sales, Inc. v. Henry Schein, Inc., on remand from the Supreme Court, in which the Fifth Circuit held: “The most natural reading of the arbitration clause at issue here states that any dispute, except actions seeking injunctive relief, shall be resolved in arbitration in accordance with the AAA rules. The plain language incorporates the AAA rules—and therefore delegates arbitrability—for all disputes except those under the carve-out. Given that carve-out, we cannot say that the Dealer Agreement evinces a ‘clear and unmistakable’ intent to delegate arbitrability.”

As for the Supreme Court’s opinion, the panel said: “We are mindful of the Court’s reminder that ‘[w]hen the parties’ contract delegates the arbitrability question to an arbitrator, the courts must respect the parties’ decision as embodied in the contract.’ But we must also heed its warning that ‘courts “should not assume that the parties agreed to arbitrate arbitrability unless there is clear and unmistakable evidence that they did so.’”‘ The parties could have unambiguously delegated this question, but they did not, and we are not empowered to re-write their agreement.” No. 16-41674 (Aug. 16, 2019).

DeJoria v. Maghreb Petroleum Exploration, S.A. presents, at first blush, an epic dispute in which “[t]he facts of this case are littered across the pages of the Federal Reporter.” A failed oil-development project in Morocco led to a $130 million judgment from the Moroccan courts. But after years of legal wrangling about the enforceability of that judgment in Texas, “despite the seeming complexity of this case—royal intrigue, a foreign proceeding, almost a billion dirhams at stake—it ends up being resolved on one of the most basic principles of appellate law: deference to the factfinder.” After confirming the correct legal framework, the Fifth Circuit found no clear error in the district court’s fact-findings. No. 18-50348 (Aug. 16, 2019).

DeJoria v. Maghreb Petroleum Exploration, S.A. presents, at first blush, an epic dispute in which “[t]he facts of this case are littered across the pages of the Federal Reporter.” A failed oil-development project in Morocco led to a $130 million judgment from the Moroccan courts. But after years of legal wrangling about the enforceability of that judgment in Texas, “despite the seeming complexity of this case—royal intrigue, a foreign proceeding, almost a billion dirhams at stake—it ends up being resolved on one of the most basic principles of appellate law: deference to the factfinder.” After confirming the correct legal framework, the Fifth Circuit found no clear error in the district court’s fact-findings. No. 18-50348 (Aug. 16, 2019).

The viability of a tort claim against T-Mobile, arising from delays in obtaining medical treatment, turned on whether this recent statement by the Texas Supreme Court was “obiter dictum” or “judicial dictum”:

Proximate cause requires both cause in fact and foreseeability. For a condition of property to be a cause in fact, the condition must serve as a substantial factor in causing the injury and without which the injury would not have occurred. When a condition or use of property merely furnishes a circumstance that makes the injury possible, the condition or use is not a substantial factor in causing the injury. To be a substantial factor, the condition or use of the property must actually have caused the injury. Thus, the use of property that simply hinders or delays treatment does not actually cause the injury and does not constitute a proximate cause of an injury.

The Fifth Circuit concluded that the statement was judicial dictum entitled to deference in an Erie analysis, and rendered summary judgment for T-Mobile. Alex v. T-Mobile USA, Inc., No. 18-10555 (June 6, 2019, unpublished) (applying City of Dallas v. Sanchez, 494 S.W.3d 722 (Tex. 2016)). (My Pepperdine Law Review article with the University of Idaho’s Wendy Couture remains a strong summary of the underlying theory.)

The complexity of the modern administrative state produces ornate procedural problems – specifically, in Wynnewood Refining Co. v. OSHRC, the challenge of two parties appealing an administrative-agency ruling to two different federal circuit courts. The solution, however, is simple, in the form of a strict “first-to-file” rule established by Congress for this problem: “Th[is] first-to-file rule governs even for petitions filed on the same day; indeed, we have applied it even when petitions were filed within a minute of each other.” The Fifth Circuit rebuffed an attempt by the agency to assert its discretion over which petition was filed first, concluding that Congress had drafted this statute to foreclose precisely such discretion. No. 19-60357 (Aug. 2, 2019).

In Brackeen v. Bernhardt, an opinion of enormous significance to Indian law, the Fifth Circuit found the Indian Child Welfare Act to be constitutional, reversing a district-court opinion that held otherwise. The Court also affirmed various Bureau of Indian Affairs regulations under the Chevron doctrine, noting, inter alia: “The mere fact that an agency interpretation contradicts a prior agency position is not fatal. Sudden and

In Brackeen v. Bernhardt, an opinion of enormous significance to Indian law, the Fifth Circuit found the Indian Child Welfare Act to be constitutional, reversing a district-court opinion that held otherwise. The Court also affirmed various Bureau of Indian Affairs regulations under the Chevron doctrine, noting, inter alia: “The mere fact that an agency interpretation contradicts a prior agency position is not fatal. Sudden and  unexplained change, or change that does not take account of legitimate reliance on prior interpretation, may be arbitrary, capricious [or] an abuse of discretion. But if these pitfalls are avoided, change is not invalidating, since the whole point of Chevron is to leave the discretion provided by the ambiguities of a statute with the implementing agency.” No. 18-11479 (Aug. 9, 2019) (citation omitted). (My colleague Paulette Miniter and I assisted Professor Seth Davis of UC-Berkeley with an amicus brief in this case, in support of the result ultimately reached by the Court.)

unexplained change, or change that does not take account of legitimate reliance on prior interpretation, may be arbitrary, capricious [or] an abuse of discretion. But if these pitfalls are avoided, change is not invalidating, since the whole point of Chevron is to leave the discretion provided by the ambiguities of a statute with the implementing agency.” No. 18-11479 (Aug. 9, 2019) (citation omitted). (My colleague Paulette Miniter and I assisted Professor Seth Davis of UC-Berkeley with an amicus brief in this case, in support of the result ultimately reached by the Court.)

After a five-week trial, three days of deliberation, and an Allen charge, the district court excused Juror No. 7. “[T]he district court found that Juror No. 7 had failed to follow instructions, exhibited a lack of candor during questioning, and had engaged in threatening behavior towards other jurors. Though defendants argue that this juror was removed for reasons that involve the deliberative process, there were sufficient independent reasons for his removal, namely, his lack of candor and his threatening behavior.” The Fifth Circuit followed Circuit precedent that “previously declined to apply the rule used by some circuits that prohibits dismissing a juror unless there is ‘no possibility’ that the failure to deliberate arises from their view of the evidence,” and instead reasons that “when the dismissal is due to a failure to be candid or a refusal to follow instructions, those are grounds that ‘do not implicate the deliberative process.’” United States v. Hodge, No. 17-20720 (Aug. 9, 2019) (applying United States v. Ebron, 683 F.3d 105 (2012)).

After a five-week trial, three days of deliberation, and an Allen charge, the district court excused Juror No. 7. “[T]he district court found that Juror No. 7 had failed to follow instructions, exhibited a lack of candor during questioning, and had engaged in threatening behavior towards other jurors. Though defendants argue that this juror was removed for reasons that involve the deliberative process, there were sufficient independent reasons for his removal, namely, his lack of candor and his threatening behavior.” The Fifth Circuit followed Circuit precedent that “previously declined to apply the rule used by some circuits that prohibits dismissing a juror unless there is ‘no possibility’ that the failure to deliberate arises from their view of the evidence,” and instead reasons that “when the dismissal is due to a failure to be candid or a refusal to follow instructions, those are grounds that ‘do not implicate the deliberative process.’” United States v. Hodge, No. 17-20720 (Aug. 9, 2019) (applying United States v. Ebron, 683 F.3d 105 (2012)).

Warren claimed that an internal investigation report for her employer, Fannie Mae, was defamatory. The Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for the defense, holding, inter alia, that the report was shielded from liability by a qualified privilege. As to Warren’s argument that the report was made with actual malice, her evidence of “things that the investigator left out of the report” did not meet the demanding standard of showing “that the report was false or recklessly disregarded the truth.” And as to her argument about excessive distribution of the report, she “offer[ed] no evidence, other than her own speculation, that any person without a valid interest received the report or was made aware of its findings.” Warren v. Fannie Mae, No. 18-11211 (Aug. 2, 2019).

Warren claimed that an internal investigation report for her employer, Fannie Mae, was defamatory. The Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for the defense, holding, inter alia, that the report was shielded from liability by a qualified privilege. As to Warren’s argument that the report was made with actual malice, her evidence of “things that the investigator left out of the report” did not meet the demanding standard of showing “that the report was false or recklessly disregarded the truth.” And as to her argument about excessive distribution of the report, she “offer[ed] no evidence, other than her own speculation, that any person without a valid interest received the report or was made aware of its findings.” Warren v. Fannie Mae, No. 18-11211 (Aug. 2, 2019).

In a remarkable letter last month, some months after an en banc argument, the federal agency at issue in the high-profile case of Collins v. Mnuchin has decided that it is in fact constitutional. The plaintiffs responded that this position shift proved their point.

In a remarkable letter last month, some months after an en banc argument, the federal agency at issue in the high-profile case of Collins v. Mnuchin has decided that it is in fact constitutional. The plaintiffs responded that this position shift proved their point.

Longoria, a truck driver in Laredo, prevailed in a 3-day jury trial about his injuries arising from an accident, and won judgment for $2.8 million in total, based on the jury’s awards as to nine types of damages. The Fifth Circuit noted these points, among others, in reviewing the defendant’s appeal of that judgment:

Longoria, a truck driver in Laredo, prevailed in a 3-day jury trial about his injuries arising from an accident, and won judgment for $2.8 million in total, based on the jury’s awards as to nine types of damages. The Fifth Circuit noted these points, among others, in reviewing the defendant’s appeal of that judgment:

- Sufficiency v. Excessiveness. “The sufficiency challenge asks only whether there is any evidence for a jury’s award; if there is, the judge’s job is at an end. An excessiveness challenge requires more extensive scrutiny, including—as will be seen—consideration of verdicts in similar cases. And we review the district court’s decision on remittitur only for an abuse of discretion. We cannot assess whether such discretion was abused if the district court was not asked to exercise it in the first instance.”

- Federal v. State. In a review for excessiveness: “The state/federal issue is presented because Texas does not use the maximum recovery rule. It instead conducts a more holistic assessment at both stages of the inquiry.”

- Pain. “This pain is significant. But an award of $1 million is ‘contrary to the overwhelming weight of the evidence,’ given that Longoria can mostly manage the pain by stretching and taking over-the-counter medicine.”

- Anguish. “Longoria points to his fear that he may be unable to keep working as a truck driver. He testified that this occupation is his ‘childhood dream’ and that without it, he could not support his family. But Longoria is cleared to work, and no doctor indicated his ability to work may change in the future. His understandable concern for the future is not the high degree of distress or frequent disruption Texas law requires.”

Longoria v. Hunter Express, No. 17-41042 (Aug. 1, 2019).