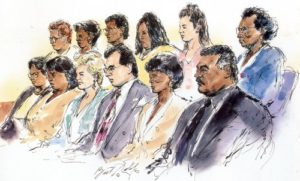

The Fifth Circuit’s recent opinion in Retractable Technologies Inc. v. Becton Dickinson Co. reversed a $340 million antitrust judgment and placed significant limits on the activity to which the antitrust laws apply. Judge Edith Jones wrote for the panel, joined by Judges Jacques Wiener and Stephen Higginson. No. 14-41384 (Dec. 2, 2016).

The Fifth Circuit’s recent opinion in Retractable Technologies Inc. v. Becton Dickinson Co. reversed a $340 million antitrust judgment and placed significant limits on the activity to which the antitrust laws apply. Judge Edith Jones wrote for the panel, joined by Judges Jacques Wiener and Stephen Higginson. No. 14-41384 (Dec. 2, 2016).

Plaintiff Retractable Technologies Inc. (“RTI”) and Defendant Beckton Dickinson (“BD”) were competing manufacturers of syringes. Retractable sued for false advertising under the Lanham Act, and alleged that BD attempted to monopolize the syringe market in violation of section 2 of Sherman Act.

As summarized by the Court, the antitrust verdict in RTI’s favor “rest[ed] upon three types of ‘deception’ by its rival: [1] patent infringement . . . [2] two false advertising claims made persistently; and [3] BD’s alleged ‘tainting the market’ for retractable syringes in which it alone competed with RTI.”

The Court found that each of these three liability theories failed.

First, as to patent infringement, the Court observed that by its very nature, a patent grants a limited monopoly. Thus, “patent infringement invades the patentee’s monopoly rights, causes competing products to enter the market, and thereby increases competition,” meaning that it “is not an injury cognizable under the Sherman Act.”

Second, the false advertising claims involved BD’s admittedly inaccurate claims to have the “world’s sharpest” needles with “low waste space.” But even these statements “may have been wrong, misleading, or debatable,’ . . . they were all “arguments on the merits, indicative of competition on the merits.” (quoting Stearns Airport Equip. Co. v. FMC Corp., 170 F.3d 518, 522 (5th Cir. 1999)).

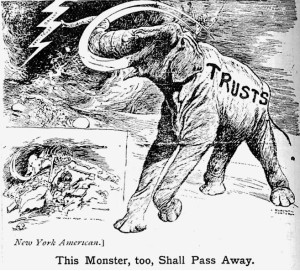

After a thorough analysis of different standards used to evaluate antitrust claims based on allegedly false advertising, the Court concluded: “The broader point . . . is the distinction embodied in our precedents between business torts, which harm competitors, and truly anticompetitive activities, which harm the market.” RTI did not make such a showing here.

After a thorough analysis of different standards used to evaluate antitrust claims based on allegedly false advertising, the Court concluded: “The broader point . . . is the distinction embodied in our precedents between business torts, which harm competitors, and truly anticompetitive activities, which harm the market.” RTI did not make such a showing here.

Finally, the “taint” claim alleged that BD refused to make needed repairs to its retractable needle design, in hopes of persuading purchasers that all such syringes – including RTI’s – were inherently unreliable, until some time after RTI’s patents expired and BD could use RTI’s design to revitalize and take over the retractable syringe market. The Court called this theory “illogical,” since selling a bad product would only serve to benefit RTI’s competitors, and would not serve BD well in any attempt to expand its brand once RTI’s technology became available.

While reversing on the antitrust claim and the substantial damages associated with it, the Court went on to remand for reconsideration of what Lanham Act remedies for false advertising might still be appropriate.

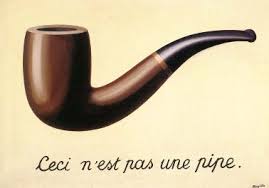

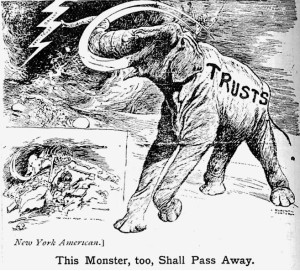

This case is a forceful reminder that a good business tort claim does not equate to a good antitrust claim – or, even any antitrust claim at all. It is also a reminder of two broader points about how the Fifth Circuit approaches business tort claims arising from federal law.

On the one hand, that Court allows vigorous litigation of federal claims within their proper boundaries, as it recently did in affirming a nine-figure judgment arising from an antitrust conspiracy claim in MM Steel LP v. JSW Steel (USA), Inc., 806 F.3d 835 (5th Cir. 2015). (Notably, Judge Stephen Higginson, who was on the panel in the Retractable case, wrote the opinion in MM Steel.)

But on the other hand, the Court carefully polices the boundaries of those claims, as it did here, and as it also did in its painstaking comparison between state law trade secret claims and federal copyright claims in GlobeRanger Corp. v. Software AG, 836 F.3d 477 (5th Cir. 2016). The “siren song” of treble damages under the Sherman Act is a compelling one, but the pathway to such damages is carefully guarded.

Sessa Capital, a hedge fund, supported the election of certain directors to the board of Ashford Prime, a hotel business. Ashford’s management rejected their applications, contending that they were incomplete. Litigation ensued, in which Sessa sought an injunction against the June 10, 2016 board election. The district court denied relief; Sessa appealed, and a motions panel of the Fifth Circuit denied an interim stay.

Sessa Capital, a hedge fund, supported the election of certain directors to the board of Ashford Prime, a hotel business. Ashford’s management rejected their applications, contending that they were incomplete. Litigation ensued, in which Sessa sought an injunction against the June 10, 2016 board election. The district court denied relief; Sessa appealed, and a motions panel of the Fifth Circuit denied an interim stay.