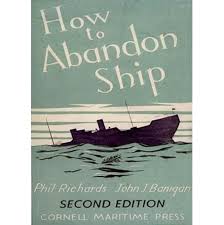

Judgment creditors garnished two oil tankers (including the M/V FMPC 30, right); the garnishees appealed as to the connection between them and the judgment debtors. After reviewing the distinction between “alter ego” theories at the jurisdictional and merits stages, the Fifth Circuit reversed. Finding that “[t]he [district court relied almost exclusively on two ‘organizational charts’ submitted by Plaintiffs (taken from Garnishees’ website),” the Court found that the charts “do not actually depict corporate structure” or ” show the functional relationship among the entities.” Accordingly, the case for “jurisdictional veil piercing” was not established and the garnishment proceeding was dismissed. Licea v. Curacao Drydock Co., No. 14-20619 (Nov. 23, 2015).

Judgment creditors garnished two oil tankers (including the M/V FMPC 30, right); the garnishees appealed as to the connection between them and the judgment debtors. After reviewing the distinction between “alter ego” theories at the jurisdictional and merits stages, the Fifth Circuit reversed. Finding that “[t]he [district court relied almost exclusively on two ‘organizational charts’ submitted by Plaintiffs (taken from Garnishees’ website),” the Court found that the charts “do not actually depict corporate structure” or ” show the functional relationship among the entities.” Accordingly, the case for “jurisdictional veil piercing” was not established and the garnishment proceeding was dismissed. Licea v. Curacao Drydock Co., No. 14-20619 (Nov. 23, 2015).

Monthly Archives: November 2015

Abandoning its reputation as a skeptic of antitrust claims, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit recently affirmed a $150 million judgment in MM Steel, L.P. v. JSW Steel (USA) Inc., a hard-fought battle among steel distributors on the Texas Gulf Coast. No. 14-20267 (Nov. 25, 2015). Judge Stephen Higginson, a relatively recent Obama appointee, wrote the opinion, joined by Judges Edith Brown Clement and Fortunato “Pete” Benavides. A likely landmark in the modern law of antitrust conspiracy, the opinion unhesitatingly applies longstanding rules about “per se” antitrust liability instead of engaging in the more complex economic analysis that has dominated in recent years. By doing so, the opinion has the potential to invigorate antitrust litigation in many situations where competing businesses allegedly join forces against another competitor.

Abandoning its reputation as a skeptic of antitrust claims, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit recently affirmed a $150 million judgment in MM Steel, L.P. v. JSW Steel (USA) Inc., a hard-fought battle among steel distributors on the Texas Gulf Coast. No. 14-20267 (Nov. 25, 2015). Judge Stephen Higginson, a relatively recent Obama appointee, wrote the opinion, joined by Judges Edith Brown Clement and Fortunato “Pete” Benavides. A likely landmark in the modern law of antitrust conspiracy, the opinion unhesitatingly applies longstanding rules about “per se” antitrust liability instead of engaging in the more complex economic analysis that has dominated in recent years. By doing so, the opinion has the potential to invigorate antitrust litigation in many situations where competing businesses allegedly join forces against another competitor.

As background, the opinion notes: “In the Gulf Coast steel industry, steel manufacturers sell about half of their steel plate to end users, including companies such as Wal-Mart, Exxon, and General Motors, and sell the other half to distributors who then resell the plate to end users.” The dispute arose when two former employees of a distributor, named Chapel Steel, formed a new distribution company called MM Steel. Chapel’s management, angry at their departure and competition, not only sued MM and its founders for violation of a non-compete agreement, but began an aggressive boycott campaign to cut off MM’s supply of steel plate and put it out of business.

Evidence showed that Chapel’s leadership enlisted other distributors in its attack on MM, and also threatened several steel manufacturers, including Nucor Corporation and JSW Steel, with a boycott if they did not refuse to deal with MM. In particular, JSW received threats from Chapel and another distributor within several weeks of each other, and shortly afterwards, cancelled a supply contract that it had earlier negotiated with MM.

MM went out of business. It sued JSW for breach of contract, and sued Chapel (and other distributors), along with Nucor, JSW, and another manufacturer. After a six-week trial, the Southern District of Texas entered judgment for over $150 million for MM, finding that the distributors formed a conspiracy in violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Act to keep steel away from MM, and that the manufacturers knowingly joined that conspiracy. The distributors settled, leaving Nucor and JSW as the only appellants by the time of the Fifth Circuit’s decision.

The opinion’s analysis began by stating the accepted legal standards in the area. A Section 1 claim requires proof that the defendants “(1) engaged in a conspiracy (2) that restrained trade (3) in a particular market.” That proof must “tend[] to exclude the possibility of independent conduct,” which in a refusal-to-deal case such as this one, means showing that the defendants’ conduct is “inconsistent with the manufacturer’s independent self-interest.”

Applying these standards, the court affirmed the liability finding as to JSW. “The fact that both [distributors’ made . . . threats within several weeks of each other was sufficient evidence for a reasonable juror to conclude that JSW was aware of the horizontal conspiracy to exclude MM from the market.” Then, when JSW responded by terminating its contract with MM, virtually guaranteeing a suit for breach, “[a] reasonable juror also could have concluded that JSW’s abrupt decision to no longer deal with MM following those threats and JSW’s statements regarding that decision tended to exclude the possibility of conduct that was independent of the distributor’s conspiracy.” While JSW contended that its actions were motivated by concern about the Chapel lawsuit against MM, the court found that “[a] reasonable juror could have concluded that JSW’s explanation for its supposedly independent refusal to deal was pretextual.”

The court reversed as to Nucor, who had received only one threat, from Chapel. In response, Nucor introduced evidence that it had an “incumbency practice,” under which it remained loyal to established customers such as Chapel, to maintain a stable supply chain. The court reasoned that “[e]ven if the jury did not credit this practice, MM did not provide evidence that when Nucor first refused to quote MM, Nucor was aware of an agreement between the distributors to foreclose MM from the market. . . . In fact, at the time Nucor first refused to quote MM, Nucor believed that JSW, its competitor, was supplying MM.”

Returning to JSW, the court observed that “[t]he Supreme Court has consistently held that the per se rule [of antitrust liability] is applicable to group boycotts identical to the boycott alleged in this case.” JSW argued that in the recent opinion of Leegin Creative Leather Products v. PSKS, 551 U.S. 877 (2007) when the Supreme Court eliminated per se liability for price-setting vertical agreements (i.e, exclusive dealing arrangements), it necessarily did so for horizontal agreements such as the one among distributors in this case. The court disagreed, concluding: “Purely vertical refusals to deal . . . frequently have procompetitive justifications, such as limiting free riding and increasing specialization. However, the crux of the group boycotts at issue in the cases in which per se liability has always applied is that members of a horizontal conspiracy use vertical agreements anticompetitively to foreclose a competitor from the market.” The court concluded by rejecting a challenge to MM’s damage model.

The MM opinion has considerable significance, both practically and theoretically. Practically, a company in a position like JSW’s is not unsympathetic – on the one hand, it has substantial contract obligations to a new customer, while on the other hand, it confronts serious threats to substantial other and longstanding business. A tough business decision becomes harder when potential Section 1 antitrust liability – which carries with it the threat of treble damages – must be considered.

Theoretically, the court’s affirmation of per se liability connects to an older school of antitrust thought that emphasized bright-line rules over case-by-case analysis. That view has received strong criticism as anachronistic; as Robert Bork wrote many years ago in a famous Yale Law Journal article: “The current shibboleth of per se illegality in existing law conveys a sense of certainty, even of automaticity, which is delusive. The per se concept does not accurately describe the law relating to agreements eliminating competition as it is, as it has been, or as it ever can be.” Yet per se rules remain in place in the antitrust laws, and the MM opinion shows that they are not going away any time soon, absent sweeping action by Congress or the Supreme Court.

After 15-plus years of litigation, the remaining issues in Art Midwest Inc. v. Clapper related to the calculation of prejudgment interest. No. 14-10973 (Nov. 9, 2015, last before the Fifth Circuit in Art Midwest Inc. v. Atl. Ltd. P’ship XII, 742 F.3d 206 (5th Cir. 2014)). The Court reversed as to the starting date for calculating interest — even though the first judgment by the district court was reversed in part, the date of that judgment was still the proper starting point under Fed. R. App. P. 37(a) and Masinter v. Tenneco Oil Co., 929 F.2d 191 (5th Cir. 1991), aff’d in relevant part, 938 F.2d 536 (5th Cir. 1991). The opinion also touches on waiver and law-of-the-case issues addressed in the 2014 appeal.

After 15-plus years of litigation, the remaining issues in Art Midwest Inc. v. Clapper related to the calculation of prejudgment interest. No. 14-10973 (Nov. 9, 2015, last before the Fifth Circuit in Art Midwest Inc. v. Atl. Ltd. P’ship XII, 742 F.3d 206 (5th Cir. 2014)). The Court reversed as to the starting date for calculating interest — even though the first judgment by the district court was reversed in part, the date of that judgment was still the proper starting point under Fed. R. App. P. 37(a) and Masinter v. Tenneco Oil Co., 929 F.2d 191 (5th Cir. 1991), aff’d in relevant part, 938 F.2d 536 (5th Cir. 1991). The opinion also touches on waiver and law-of-the-case issues addressed in the 2014 appeal.

Fortune Natural Resources made a claim in the bankruptcy of an oil exploration company for roughly $3 million related to decommisioning a lease. Fortune alleged that adjustments to a sale order hurt its right of recovery on that claim. The Fifth Circuit disagreed and found no standing, observing: “Fortune’s argument that it meets the ‘person aggrieved’ standard because it has already received a letter from . . . mandating that it decommission its Lease misses the mark. Fortune’s payment of decommissioning costs may show an injury, but it does not show that the bankruptcy court’s order caused this injury. This court’s jurisprudence states that the order of the bankruptcy court must directly and adversely affect the appellant pecuniarily. Having failed to present sufficient evidence to show that Fortune was directly and adversely affected pecuniarily by the order of the bankruptcy court, Fortune does not meet the ‘person aggrieved” test.” Fortune Natural Resources Corp. v. United States Dep’t of the Interior, No. 15-20151 (Nov. 19, 2015, unpublished).

Fortune Natural Resources made a claim in the bankruptcy of an oil exploration company for roughly $3 million related to decommisioning a lease. Fortune alleged that adjustments to a sale order hurt its right of recovery on that claim. The Fifth Circuit disagreed and found no standing, observing: “Fortune’s argument that it meets the ‘person aggrieved’ standard because it has already received a letter from . . . mandating that it decommission its Lease misses the mark. Fortune’s payment of decommissioning costs may show an injury, but it does not show that the bankruptcy court’s order caused this injury. This court’s jurisprudence states that the order of the bankruptcy court must directly and adversely affect the appellant pecuniarily. Having failed to present sufficient evidence to show that Fortune was directly and adversely affected pecuniarily by the order of the bankruptcy court, Fortune does not meet the ‘person aggrieved” test.” Fortune Natural Resources Corp. v. United States Dep’t of the Interior, No. 15-20151 (Nov. 19, 2015, unpublished).

A mortgage servicer can violate the Texas Finance Code by asserting legal rights it does not actually have. See McCaig v. Wells Fargo Bank, 788 F.3d 463 (5th Cir. 2015). But seemingly inconsistent communications by a servicer do not violate the Code:

A mortgage servicer can violate the Texas Finance Code by asserting legal rights it does not actually have. See McCaig v. Wells Fargo Bank, 788 F.3d 463 (5th Cir. 2015). But seemingly inconsistent communications by a servicer do not violate the Code:

“[Plaintiff] does not contend that any one letter is a misrepresentation in

and of itself but rather that the amounts differ, so the letters are misleading

as a whole. But the letters explicitly state that they are describing two different

types of obligations: notices of the entire outstanding obligation and notices

of the amount due to bring the loan current. Each category is internally consistent

and consistent with the other. [Plaintiff’s] amount to bring the loan current

continued to grow over time because she was not making adequate payments

and still occupied the property. The total outstanding obligation grew for the

same reason. The letters were not misrepresentations but, instead, were

accurate descriptions of two different types of obligations and were specifically

identified as such.”

Rucker v. Bank of America, 15-10373 (Nov. 20, 2015).

Cameron International, a main defendant in the Deepwater Horizon cases, successfully sued Liberty Insurance to help cover its substantial settlement costs. After affirming on the merits, the Fifth Circuit certified this question to the Texas Supreme Court: “Whether, to maintain a cause of action under Chapter 541 of the Texas Insurance Code against an insurer that wrongfully withheld policy benefits, an insured must allege and prove an injury independent from the denied policy benefits?” Cameron International Corp. v. Liberty Ins. Underwriters, Inc., No. 14-31321 (Nov. 19, 2015).

Cameron International, a main defendant in the Deepwater Horizon cases, successfully sued Liberty Insurance to help cover its substantial settlement costs. After affirming on the merits, the Fifth Circuit certified this question to the Texas Supreme Court: “Whether, to maintain a cause of action under Chapter 541 of the Texas Insurance Code against an insurer that wrongfully withheld policy benefits, an insured must allege and prove an injury independent from the denied policy benefits?” Cameron International Corp. v. Liberty Ins. Underwriters, Inc., No. 14-31321 (Nov. 19, 2015).

The district court in Naranjo v. Thompson found that Naranjo, a prisoner in the Reeves County Detention Center, had shown “exceptional circumstances” that warranted the appointment of counsel to pursue his civil rights claims about the conditions of his incarceration. (Foremost among them was the prisoner’s inability to review a number of documents that were filed under seal due to security concerns.) The court went on to conclude, however, that no local attorneys were available and that it lacked the power to make a compulsory appointment. The Fifth Circuit reversed, finding that a district court has the inherent power to make such an appointment, but reminding that “this is a power of last resort” and that “[i]nherent powers ‘must be used with great restraint and caution.'” Accordingly, the Court reversed a summary judgment for the defendants and remanded for proceedings consistent with its ruling about inherent power.

U.S. Bank sent notices of acceleration, and began foreclosure proceedings, several times before suing for judicial foreclosure. The borrowers contended that suit was time-barred. The Fifth Circuit disagreed, finding that the bank’s second notice “unequivocally manifested an intent to abandon the previous acceleration and provided the [borrowers] with an opportunity to avoid foreclosure if they cured their arrearage. As a result, the statute of limitations period under [Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code] § 16.035(a) ceased to run at that point and a new limitations period did not begin to accrue until [they] defaulted again and U.S. Bank exercised its right to accelerate thereafter.” Boren v. U.S. Nat’l Bank Ass’n. No. 14-20718 (Oct. 26, 2015).

U.S. Bank sent notices of acceleration, and began foreclosure proceedings, several times before suing for judicial foreclosure. The borrowers contended that suit was time-barred. The Fifth Circuit disagreed, finding that the bank’s second notice “unequivocally manifested an intent to abandon the previous acceleration and provided the [borrowers] with an opportunity to avoid foreclosure if they cured their arrearage. As a result, the statute of limitations period under [Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code] § 16.035(a) ceased to run at that point and a new limitations period did not begin to accrue until [they] defaulted again and U.S. Bank exercised its right to accelerate thereafter.” Boren v. U.S. Nat’l Bank Ass’n. No. 14-20718 (Oct. 26, 2015).

Robert Namer had a Louisiana business that used the name “Voice of America,” and encountered intellectual property trouble with the Voice of America information service operated by the U.S. Government. (Incidentally, I recommend some study of the VOA’s “Simple English” programming, which uses a 1,500-word vocabulary, for anyone interested in straightforward writing.) Namer lost at trial and challenged the VOA’s audience survey on appeal. The Fifth Circuit affirmed: “It was appropriate for [the VOA’s expert] to survey potential consumers of

Robert Namer had a Louisiana business that used the name “Voice of America,” and encountered intellectual property trouble with the Voice of America information service operated by the U.S. Government. (Incidentally, I recommend some study of the VOA’s “Simple English” programming, which uses a 1,500-word vocabulary, for anyone interested in straightforward writing.) Namer lost at trial and challenged the VOA’s audience survey on appeal. The Fifth Circuit affirmed: “It was appropriate for [the VOA’s expert] to survey potential consumers of  Namer’s website to determine if they might be confused into believing they were viewing the website of the government-run VOA (and 19.1% of them were confused.)” The Court also rejected a laches argument because Namer did not show prejudice; “[c]ontinued routine use of the website during the time when the Board allegedly sat on its rights is all that Namer has established.” Namer v. Voice of America, No. 14-31353 (Oct. 26, 2015, unpublished). The opinion helpfully summarizes recent Circuit authority on both the survey and laches issues.

Namer’s website to determine if they might be confused into believing they were viewing the website of the government-run VOA (and 19.1% of them were confused.)” The Court also rejected a laches argument because Namer did not show prejudice; “[c]ontinued routine use of the website during the time when the Board allegedly sat on its rights is all that Namer has established.” Namer v. Voice of America, No. 14-31353 (Oct. 26, 2015, unpublished). The opinion helpfully summarizes recent Circuit authority on both the survey and laches issues.

T reaty Energy sued for its damages after an involuntary bankruptcy petition against it was dismissed. One of its claims sought damages for losses in connection with attempts to sell its restricted stock during that period. The Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for the defendants, noting: (1) “Though the sales price of restricted shares did fluctuate, it averaged 0.5¢ immediately before, during, and after the pendency of the involuntary petition, and (2) the affiant about an alleged plan to sell restricted shares at a substantial discount lacked personal knowledge, claiming only that he “did assist in the process when requested, which included gathering information when given direct instructions by his superiors.” Treaty Energy Corp. v. Hallin, No. 15-30113 (Oct. 27, 2015, unpublished).

reaty Energy sued for its damages after an involuntary bankruptcy petition against it was dismissed. One of its claims sought damages for losses in connection with attempts to sell its restricted stock during that period. The Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for the defendants, noting: (1) “Though the sales price of restricted shares did fluctuate, it averaged 0.5¢ immediately before, during, and after the pendency of the involuntary petition, and (2) the affiant about an alleged plan to sell restricted shares at a substantial discount lacked personal knowledge, claiming only that he “did assist in the process when requested, which included gathering information when given direct instructions by his superiors.” Treaty Energy Corp. v. Hallin, No. 15-30113 (Oct. 27, 2015, unpublished).

In an opinion with enormous policy impact, the Fifth Circuit has affirmed the injunction of President Obama’s executive actions about immigration. Texas v. United States, No. 15-40238 (revised Nov. 25, 2015). Judge Smith wrote for the 2-judge majority, joined by Judge Elrod — an unsurprising outcome, since they formed the majority in the Court’s earlier opinion that denied an interim stay. Judge King dissented. A petition for Supreme Court review is a certainty. A good representative article about the decision appears in The Atlantic.

In an opinion with enormous policy impact, the Fifth Circuit has affirmed the injunction of President Obama’s executive actions about immigration. Texas v. United States, No. 15-40238 (revised Nov. 25, 2015). Judge Smith wrote for the 2-judge majority, joined by Judge Elrod — an unsurprising outcome, since they formed the majority in the Court’s earlier opinion that denied an interim stay. Judge King dissented. A petition for Supreme Court review is a certainty. A good representative article about the decision appears in The Atlantic.

The full Fifth Circuit has voted to rehear en banc the case of Flagg v. Stryker Corporation, a deceptively complicated dispute about the role of a pre-suit review process in determining how to consider a medical malpractice claim in the analysis of the parties’ citizenship.

The Pyes’ home, valued at $195,000 before Hurricane Ike, was destroyed by that storm. After they recovered under various insurance policies, the Fifth Circuit found that further recovery under a flood insurance policy would be an impermissible double recovery. Noting that federal common law applied in this area rather than Texas law, the Court nevertheless found that Texas’s emphasis on fair market value was persuasive, and set the $195,000 valuation as the cap on recovery. While reaching this result, the Court reminded that “the question of the proper measure of recovery under a policy, which is controlled by policy language when defined in the contract as it is here, as distinct from the question of how the bar on double recovery is applied.” Pye v. Fidelity Nat’l Prop. & Cas. Ins. Co., No. 14-40315 (Nov. 6, 2015).

The Pyes’ home, valued at $195,000 before Hurricane Ike, was destroyed by that storm. After they recovered under various insurance policies, the Fifth Circuit found that further recovery under a flood insurance policy would be an impermissible double recovery. Noting that federal common law applied in this area rather than Texas law, the Court nevertheless found that Texas’s emphasis on fair market value was persuasive, and set the $195,000 valuation as the cap on recovery. While reaching this result, the Court reminded that “the question of the proper measure of recovery under a policy, which is controlled by policy language when defined in the contract as it is here, as distinct from the question of how the bar on double recovery is applied.” Pye v. Fidelity Nat’l Prop. & Cas. Ins. Co., No. 14-40315 (Nov. 6, 2015).

Cordero, a district sales manager for Avon, contended that she was due a $70,850 bonus for the first quarter of 2013. Avon paid her $1,200, noting that several sales leaders who reported to her had created roughly $450,000 of fraudulent orders (although Cordero was not involved). Nevertheless, Cordero contended that the terms “met” and “achievement”

Cordero, a district sales manager for Avon, contended that she was due a $70,850 bonus for the first quarter of 2013. Avon paid her $1,200, noting that several sales leaders who reported to her had created roughly $450,000 of fraudulent orders (although Cordero was not involved). Nevertheless, Cordero contended that the terms “met” and “achievement”  in her compensation agreement referred to product that was “ordered, shipped, and notated on Avon’s quarterly report.” The Fifth Circuit agreed with Avon that those terms necessarily referred to legitimate activity; otherwise, the contract did not advance a sensible business goal. Cordero v. Avon Products, No. 15-40563 (Oct. 29, 2015, unpublished).

in her compensation agreement referred to product that was “ordered, shipped, and notated on Avon’s quarterly report.” The Fifth Circuit agreed with Avon that those terms necessarily referred to legitimate activity; otherwise, the contract did not advance a sensible business goal. Cordero v. Avon Products, No. 15-40563 (Oct. 29, 2015, unpublished).

Cardoni v. Prosperity Bank, an appeal from a preliminary injunction ruling in a noncompete case, involved a clash between Texas and Oklahoma law, and led to these noteworthy holdings from the Fifth Circuit in this important area for commercial litigators:

Cardoni v. Prosperity Bank, an appeal from a preliminary injunction ruling in a noncompete case, involved a clash between Texas and Oklahoma law, and led to these noteworthy holdings from the Fifth Circuit in this important area for commercial litigators:

- Under the Texas Supreme Court’s weighing of the relevant choice-of-law factors, Oklahoma has a stronger interest in the enforcement of a noncompete than Texas, “with the employees located in Oklahoma and employer based in Texas”;

- As also noted by that Court, “Oklahoma has a clear policy against enforcement of most noncompetition agreements,” which is not so strong as to nonsolicitation agreements;

- The district court did not clearly err in declining to enforce a nondisclosure agreement, given the unsettled state of Texas law on the “inevitable disclosure” doctrine; and

- “[T]he University of Texas leads the University of Oklahoma 61-44-5 in the Red River Rivalry.”

No. 14-20682 (Oct. 29, 2015).

The Howard Hughes Company sold lots, and provided necessary infrastructure, in a planned development near Las Vegas. The IRS did not let it take advantage of a special gain calculation for “home construction contracts,” and the Fifth Circuit agreed. The key statutory interpretation principle (after the basic one that tax exemptions are strictly construed) was “the rule against superfluities,” under which an argument about one statutory provision fails if it makes another one redundant. Howard Hughes Co. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, No. 14-60915 (revised Dec. 7, 2015).

The Howard Hughes Company sold lots, and provided necessary infrastructure, in a planned development near Las Vegas. The IRS did not let it take advantage of a special gain calculation for “home construction contracts,” and the Fifth Circuit agreed. The key statutory interpretation principle (after the basic one that tax exemptions are strictly construed) was “the rule against superfluities,” under which an argument about one statutory provision fails if it makes another one redundant. Howard Hughes Co. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, No. 14-60915 (revised Dec. 7, 2015).