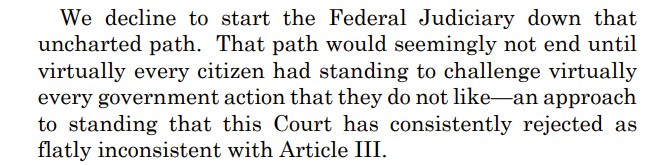

In Deep South Center of Environmental Justice v. EPA, the Fifth Circuit addressed the requirements for organizational standing and the limits of remote injury, implementing the Supreme Court’s recent decision in FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine as follows:

In Deep South Center of Environmental Justice v. EPA, the Fifth Circuit addressed the requirements for organizational standing and the limits of remote injury, implementing the Supreme Court’s recent decision in FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine as follows:

- An organization cannot establish standing just by diverting resources to oppose a government action or by incurring costs for advocacy in response to that action: “An organizational plaintiff ‘cannot spend its way into standing simply by expending money to gather information and advocate against the defendant’s action.’”

- Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine requires a “concrete and demonstrable injury to the organization’s activities,” not just a “setback to [its] abstract social interests.” Thus, direct interference with an organization’s core business activities (as in other precedent) is distinct from voluntary changes in programming or advocacy, which are not enough.

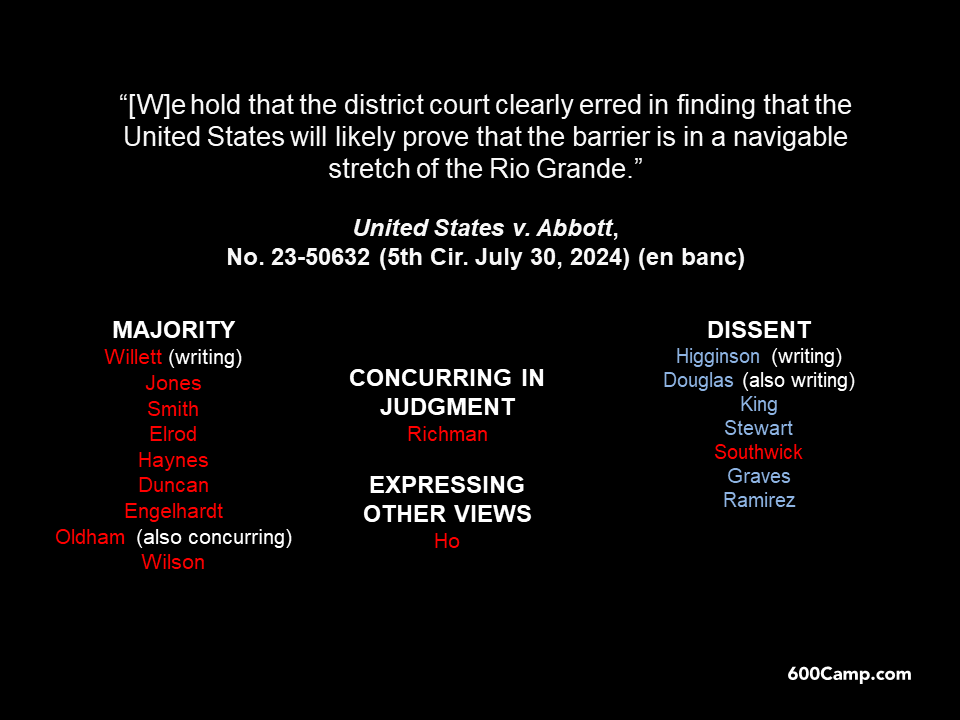

- The panel majority described the petitioners’ claims of future economic, health, property, aesthetic, and recreational injuries as resting on a multi-step chain: a party would have to apply for a permit, the state would have to issue it, a well would have to be constructed and operated, and then some mishap would have to occur that would directly harm the petitioners or their members. And even where some steps had already occurred (such as the filing of permit applications), the other ones—such as the likelihood of a well malfunctioning at a time and place and injuring a specific member—remained speculative.

A dissent concurred in the judgment but questioned the extent of the majority’s holdings about the impact of Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine. No. 24-60084, May 21, 2025.