Six Keys to Legal Writing

I often edit legal writing, especially initial drafts prepared by associate attorneys, and this page condenses the main points that guide my writing and editing. I hope you find them useful in your work. I owe a great debt to Strunk & White and several of these items derive from their wonderful book, “The Elements of Style.” Another outstanding book about the writing process is Verlyn Klinkenborg’s “Several Short Sentences About Writing,” and Judge John Minor Wisdom’s short essay “Wisdom’s Idiosyncrasies,” 109 Yale L.J. 1273 (1999), is a classic. The following are my six main tips for quality legal writing.

I often edit legal writing, especially initial drafts prepared by associate attorneys, and this page condenses the main points that guide my writing and editing. I hope you find them useful in your work. I owe a great debt to Strunk & White and several of these items derive from their wonderful book, “The Elements of Style.” Another outstanding book about the writing process is Verlyn Klinkenborg’s “Several Short Sentences About Writing,” and Judge John Minor Wisdom’s short essay “Wisdom’s Idiosyncrasies,” 109 Yale L.J. 1273 (1999), is a classic. The following are my six main tips for quality legal writing.

1. Avoid needless words.

1. Avoid needless words.

Strunk & White: “Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that he make every word tell.”

2. Use shorter words.

3. Use shorter sentences.

Klinkenborg: “A crowded sentence . . . betrays the writer’s lassitude, [t]he lazy shuffling of words together into a single sentence [i]nstead of deciding what really matters [a]nd finding the verbal energy to construct separate sentences.”

A letter I once wrote about deposition dates illustrates the power of brevity. In a more serious vein, an excellent 2019 analysis of Robert Mueller’s writing by Thomas Dean notes: “A plain style can have political implications.”

The Voice of America has a broadcast in Basic English — a simple vocabulary of around 1,500 words. It’s remarkable how much information gets conveyed. Worth a visit.

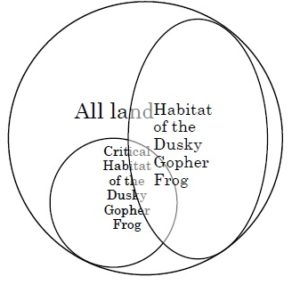

And the old adage that “a picture is worth a thousand words” still has great power; a 2017 Fifth Circuit opinion effectively uses a pair of Venn diagrams to simplify a complicated issue about the Endangered Species Act.

And the old adage that “a picture is worth a thousand words” still has great power; a 2017 Fifth Circuit opinion effectively uses a pair of Venn diagrams to simplify a complicated issue about the Endangered Species Act.

Having said that, brief does not mean dull. A young Winston Churchill offers five useful rhetorical tools in his 1897 essay, “The Scaffolding of Rhetoric” – tools that echoed in his World War II speeches, especially his “Never Surrender” address to the House of Commons. And while the playful tone of The Onion‘s 2022 Supreme Court amicus brief is not for all occasions, the writing sparkles and every sentence is a well-balanced part of the entire product.

4. Avoid passive voice.

An extreme position about passive voice appears in the concept of E-Prime. I don’t endorse its use, but E-Prime does provide valuable lessons to writers unable to shake excess ive use of the verb “be.”

ive use of the verb “be.”

In the same spirit, Rebecca Johnson’s “[verb] by zombies” test is a great way to smoke out passive voice.

My passive voice brief highlights the practical problem of a return of service that did not clearly identify the process server (the matter settled before the First Court of Appeals in Houston ruled). The Dallas Court of Appeals addresses a similar issue in U.S. Bank v. Pinkerton Consulting, agreeing with the basic position in my brief.

5. There is no good writing. Only good re-writing.

It’s not clear who said this — Internet sources generally identify Louis Brandeis, but without citation. But the statement is spot-on, especially in the age of advanced word processing. You have the technical ability to constantly revise all aspects of written work until completion, and should take full advantage of that opportunity, even if you do no more than take a free minute to change a word or two. (Or in the case of blogging, one never really completes . . .) And if you are fortunate enough to have a friend who is a gifted line editor, as described in this wonderful 2019 article in Literary Hub, by all  means keep that friend happy and ask for his or her feedback!

means keep that friend happy and ask for his or her feedback!

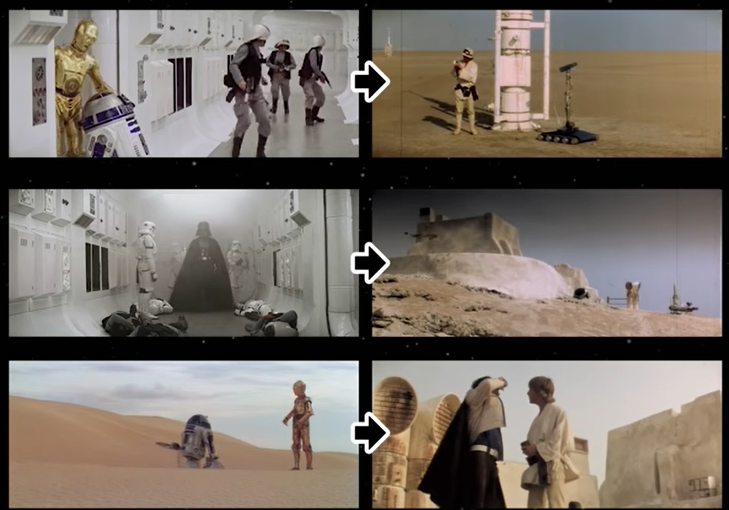

By no means are writers the only creators who must edit and revise – this excellent video explains how the post-production editors of Star Wars salvaged a hit movie from the initial, bloated and hard-to-follow rough version.

6. Look good.

A surprisingly active community writes about typography as applied to legal briefs; the Seventh Circuit’s statement of “Requirements and Suggestions” is a good summary of key points. Personally, I have preferred (a) Palatino Linotype (the official font of the Seventh Circuit’s opinions) as a font, (b) one space after a period, believing that it looks better with modern proportionally-spaced fonts than two spaces, and (c) using “citational footnotes,” although I understand and appreciate the arguments against them and often will not use them if it feels distracting for a particular brief or motion.

A surprisingly active community writes about typography as applied to legal briefs; the Seventh Circuit’s statement of “Requirements and Suggestions” is a good summary of key points. Personally, I have preferred (a) Palatino Linotype (the official font of the Seventh Circuit’s opinions) as a font, (b) one space after a period, believing that it looks better with modern proportionally-spaced fonts than two spaces, and (c) using “citational footnotes,” although I understand and appreciate the arguments against them and often will not use them if it feels distracting for a particular brief or motion.

Reasonable minds can differ about all of those preferences (except, perhaps, as to the “Comic Sans” font.) My point is simply that, especially for a reader pressed for time, good writing should also look professional and be easy on the reader’s eyes.

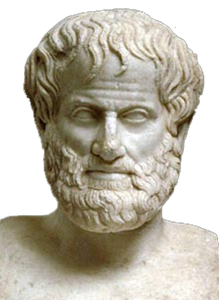

THEORY: Good writing, like all good communication, balances three factors: (1) the personal credibility of the author; (2) the logical and analytical appeal of the subject; and  (3) the emotional appeal of the subject. Aristotle called these points “ethos, logos, and pathos.”

(3) the emotional appeal of the subject. Aristotle called these points “ethos, logos, and pathos.”

Several years ago I wrote an article about how these principles apply to the highly technical issue of selecting appropriate citations to legal authority. While somewhat dry, the article shows the pervasiveness and importance of these principles in every aspect of written communication. By far, the best general work I have read on advocacy generally is Trying Cases to Win by Herbert Stern, which is based on the practical application of Aristotle’s principles in the courtroom.

On the more practical side, two short and useful references about common flaws in argument structure (“logos,” in Aristotle’s terminology) are “An Illustrated Book of Bad Arguments” by Ali Almossawi, and Darrell Huff’s 1954 classic, “How to Lie With Statistics.”