Ramirez v. Paloma Energy, No. 21-30536 (Oct. 12, 2022, unpublished), provides a clean example of affirmance on a ground presented by the record, independent of the district court’s opinion:

Category Archives: Summary Judgment Procedure

Seigler v. Wal-Mart Stores LLC presented the question whether a summary-judgment  affidavit in a slip-and-fall case was an impermissible “sham” that contradicted prior deposition testimony.

affidavit in a slip-and-fall case was an impermissible “sham” that contradicted prior deposition testimony.

The district court “identified four discrepancies between Seigler’s deposition testimony and affidavit pertaining to (1) the substance’s color, (2) its temperature and consistency, (3) its size, and (4) whether she touched the substance,” and struck the affidavit.

The Fifth Circuit disagreed, reviewing each of the claimed inconsistencies. In particular, as to the issue of “temperature and consistency,” the Court reasoned:

” Wal-Mart argues that Seigler’s affidavit testimony that the substance was ‘cold,’ ‘congealed,’ and ‘thicken[ed] up’ contradicted her deposition testimony because Seigler testified at her deposition that (1) she had no ‘personal knowledge’ or ‘evidence’ of how long the grease had been on the floor and (2) that the substance was ‘liquid.’ However, we disagree that there was a contradiction. First, we agree with Seigler that a non lawyer deponent is not expected to understand the legal significance of the terms ‘personal knowledge’ and ‘evidence.’ Second, while the discrepancies between Seigler’s deposition and affidavit may call her credibility into question, we do not think they rise to the level of a contradiction or an inherent inconsistency, because the testimony can be reconciled.

Seigler described the substance as ‘some sort of greasy liquid’ at her deposition, but she was not asked questions about its temperature or consistency. Later, in her affidavit, she described the grease as ‘cold,’ ‘congealed,’ and ‘thicken[ed] up.’ These descriptions are not mutually exclusive, nor are they necessarily contradictory. In other words, it is possible that ‘some sort of greasy liquid’ could also be ‘cold,’ ‘congealed’ and ‘thicken[ed] up.’ Thus, we think the proper course in this case is to allow a jury to evaluate the testimony’s credibility.”

No. 20-11080 (April 6, 2022) (citations omitted).

An argument that a summary-judgment motion was granted prematurely failed when:

An argument that a summary-judgment motion was granted prematurely failed when:

“[T]he response did not ‘identify specific facts below that would alter the district court’s analysis’ or in any way /demonstrate . . . how the additional discovery would likely create a genuine [dispute] of material fact.’ Rather, it simply asserted that ‘no depositions have been held, nor have interrogatories, requests for admission, nor requests for documents been exchanged between the parties’ and that the ‘defendant has repeatedly failed to provide evidence of its allegations despite numerous opportunities to do so.'”

MDK v. Proplant, No.21-20207(Feb. 9, 2022) (mem. op.).

Key aspects of an asbestos-exposure case presented genuine issues of material fact, rather than impermissible speculation, and made summary judgment inappropriate:

- Potential exposure to airborne material. “[T]he MDL court accepted that Williams worked, for some amount of time, in a building that had asbestos, and expert testimony indicates the asbestos was deteriorating and becoming airborne during his tenure. An inference taken in favor of the non-moving party would be that Williams, who for some amount of time had to breathe in the spaces where asbestos was deteriorating, was exposed to this airborne asbestos. The MDL court, though, found that there was ‘no evidence that [Williams] was ever exposed to respirable asbestos dust at any location in the facility'” (the Court also noted expert testimony on this point);

- Location at a key time. “[I]n a summary judgment order rendered that same day regarding another defendant, the MDL court relied on evidence that Williams saw individuals in moon suits to assume he was present during the asbestos remediation. Just the opposite seems to have been inferred here, as the MDL court in Boeing’s summary judgment order stated that there was ‘no evidence that [Williams] was working nearby (or in that building at all) when that remediation work was performed”;

- Excluding alternative possible locations at the key time. “[T]he MDL court also found that the evidence that Williams primarily worked in Building 350 was not ‘sufficiently specific’ to allow a jury to conclude he was exposed to asbestos during an abatement project because ‘[t]he evidence that Decedent primarily worked in Building 350 does not exclude the possibility that he was not working there during the asbestos abatement project.’ Finding to the contrary, the MDL court found, ‘would be impermissibly speculative.’ We conclude that ‘speculation’ would not be involved, only a potentially reasonable inference.”

Williams v. Boeing Co., No. 18-31158 (Jan. 18, 2022).

In a coverage dispute between two excess carriers, the Fifth Circuit observed: “At bottom, the allocation issue depends upon the sufficiency of Great American’s summary judgment evidence. To support its allocation theory and establish that the covered claims were worth at least $7 million, Great American submitted the affidavits of (1) Brent Anderson, Liberty Tire’s attorney in the Underlying Litigation, and (2) Carol Euwema, Great American’s lead adjuster for the relevant claims.” Great Am. Ins. Co. v. Employers Mut. Cas. Co. The trial court found those affidavits conclusive, but the Fifth Circuit disagreed; they provide good references for summary-judgment practice generally. No. 20-11113 (Nov. 17, 2021).

In a coverage dispute between two excess carriers, the Fifth Circuit observed: “At bottom, the allocation issue depends upon the sufficiency of Great American’s summary judgment evidence. To support its allocation theory and establish that the covered claims were worth at least $7 million, Great American submitted the affidavits of (1) Brent Anderson, Liberty Tire’s attorney in the Underlying Litigation, and (2) Carol Euwema, Great American’s lead adjuster for the relevant claims.” Great Am. Ins. Co. v. Employers Mut. Cas. Co. The trial court found those affidavits conclusive, but the Fifth Circuit disagreed; they provide good references for summary-judgment practice generally. No. 20-11113 (Nov. 17, 2021).

The dispute in Guzman v. Allstate Assurance Co. was whether the insured was a smoker when he applied for insurance; the Fifth Circuit concluded that “self-serving” affidavits by family members were sufficient to raise a fact issue and avoid summary judgment. The details offer an excellent, general example about this sort of affidavit:

The dispute in Guzman v. Allstate Assurance Co. was whether the insured was a smoker when he applied for insurance; the Fifth Circuit concluded that “self-serving” affidavits by family members were sufficient to raise a fact issue and avoid summary judgment. The details offer an excellent, general example about this sort of affidavit:

“Mirna’s and Martha’s affidavits are competent summary judgment evidence. They are based on personal knowledge, set out facts that are admissible in evidence, are given by competent witnesses, and are particularized rather than vague or conclusory. Mirna and Martha testify about their personal experiences with Guzman. In her deposition and affidavit, Mirna claimed that Guzman was not a smoker; that she was often with Guzman and would know if he smoked; that she is “able to tell whether [people] use tobacco because they have a peculiar and specific smoke smell”; and that neither Guzman nor his belongings, including his clothes and truck, ever smelled like smoke. Martha made substantially similar claims in her own affidavit. Though self-serving, this testimony is sufficient to—and does— create a genuine dispute of material fact.”

No. 21-10023 (Nov. 10, 2021).

“[T]he district court erred by failing to give notice to the parties. We ask, then, whether that error was harmless. Lexon argues that, had it received notice, it would have submitted different evidence of the value of its ‘lost collateral’—less than the full amount of the letters of credit. Lexon argues that the lost collateral, while perhaps not being worth the full value of the letters of credit, ‘had at least some economic value.’ However, Lexon never pleaded nor argued in the district court that its damages could be anything less than the full value of the letters of credit—$9,985,500. If the district court did not have an opportunity to rule on an argument, we will not address it on appeal.” Lexon Ins. Co. v. FDIC, No. 20-30173 (Aug. 2, 2021) (footnote and citation omitted) (emphasis added).

There’s always “that” customer, who brings rude remarks and behavior along with repeat business. In Sansone v. Jazz Casino Co., No. 20-30640 (Sept. 1, 2021), “that” customer led to a prima facie case about a hostile work environment: “The unidentified Harrah’s customer frequently asked Sansone about her sex life and expressed his desire to sleep with her. He commented on her breasts and physical appearance and directed sexual gestures towards her. His comments were made in the presence of others and occurred at least two times a week for a significant period of time. This contrasts with instances where we have held a smaller stint within a lengthy period of employment was not sufficiently pervasive to support a hostile work environment claim.” (citations omitted, applying Farpella-Crosby v. Horizon Health Care, 97 F.3d 803, 806 (5th Cir. 1996)).

There’s always “that” customer, who brings rude remarks and behavior along with repeat business. In Sansone v. Jazz Casino Co., No. 20-30640 (Sept. 1, 2021), “that” customer led to a prima facie case about a hostile work environment: “The unidentified Harrah’s customer frequently asked Sansone about her sex life and expressed his desire to sleep with her. He commented on her breasts and physical appearance and directed sexual gestures towards her. His comments were made in the presence of others and occurred at least two times a week for a significant period of time. This contrasts with instances where we have held a smaller stint within a lengthy period of employment was not sufficiently pervasive to support a hostile work environment claim.” (citations omitted, applying Farpella-Crosby v. Horizon Health Care, 97 F.3d 803, 806 (5th Cir. 1996)).

The practical problems cause by conversion of a Rule 12 motion to one for summary judgment were examined in Lexon Ins. Co. v. FDIC, where the nonmovant argued that “had it received [proper] notice, it would have submitted different evidence of the value of its ‘lost collateral,'” but the Fifth Circuit rejected that argument because the nonmovant “never pleaded nor argued in the district court that its damages could be anything less than the full value of the letters of credit ….” No. 20-30173 (Aug. 2, 2021).

A triable fact issue on the issue of pretext arose in Lindsey v. Bio-Medical Applications: “As anyone who has ever worked in an office environment can attest, there are real deadlines and hortatory ones—and everyone understands the difference between the two. Missing real deadlines results in actual adverse consequences for employer and employee alike—while failing to meet hortatory deadlines does not. BMA does not point to any adverse impact that Lindsey’s tardy reports had on the company. And in any event, there is no evidence BMA ever warned Lindsey that failure to submit the reports on time could jeopardize her job. So there is a genuine issue of material fact as to whether BMA’s assertion that it fired Lindsey for this reason is ‘unworthy of credence.'” No. 20-30289 (Aug. 16, 2021).

A triable fact issue on the issue of pretext arose in Lindsey v. Bio-Medical Applications: “As anyone who has ever worked in an office environment can attest, there are real deadlines and hortatory ones—and everyone understands the difference between the two. Missing real deadlines results in actual adverse consequences for employer and employee alike—while failing to meet hortatory deadlines does not. BMA does not point to any adverse impact that Lindsey’s tardy reports had on the company. And in any event, there is no evidence BMA ever warned Lindsey that failure to submit the reports on time could jeopardize her job. So there is a genuine issue of material fact as to whether BMA’s assertion that it fired Lindsey for this reason is ‘unworthy of credence.'” No. 20-30289 (Aug. 16, 2021).

While Olivarez v. T-Mobile involved the high-profile topic of Title VII’s protection for transgendered individuals, it turned on a basic and common proof problem in such cases: “Olivarez has failed to plead any facts indicating less favorable treatment than others ‘similarly situated’ outside of the asserted protected class. In fact, the Second Amended Complaint does not contain any facts about any comparators at all. The complaint simply indicates that Olivarez took six months of leave from September 2017  to February 2018—including an extension granted by T-Mobile and Broadspire—and that when Olivarez requested additional leave in March 2018, T-Mobile denied the request and terminated Olivarez’s employment in April 2018. Notably, there is no allegation that any non-transgender employee with a similar job and supervisor and who engaged in the same conduct as Olivarez received more favorable treatment.” No. 20-20463 (May 12, 2021) (emphasis added).

to February 2018—including an extension granted by T-Mobile and Broadspire—and that when Olivarez requested additional leave in March 2018, T-Mobile denied the request and terminated Olivarez’s employment in April 2018. Notably, there is no allegation that any non-transgender employee with a similar job and supervisor and who engaged in the same conduct as Olivarez received more favorable treatment.” No. 20-20463 (May 12, 2021) (emphasis added).

Douglas v. Wells Fargo Bank notes two different approaches that the Fifth Circuit has taken to an aspect of summary-judgment practice: “We have previously addressed the issue of new claims raised for the first time in response to a motion for summary judgment. We have taken two different approaches. The first approach states that a ‘claim which is not raised in the complaint but, rather, is raised only in response to a motion for summary judgment is not properly before the court.’ The second approach

instructs the district court to treat a new claim raised in response to a motion for summary judgment as a request for leave to amend. The district court must then determine whether leave should be granted.” No. 18-11567 (March 26, 2021) (footnotes omitted).

An unusual procedural path, winding through a bankruptcy proceeding, led the Fifth Circuit to review a state-court summary judgment. On the issue of the state court’s evidentiary rulings, the Court applied a federal-court approach to a standard form of Texas practice, reasoning: “The grant of these objections improperly excluded important evidence from consideration. To start, the state trial court offered no explanation as to why it granted the objections. It simply checked boxes on a form saying that the objections were sustained. Since a trial court can abuse its discretion by failing to explain the reasons for excluding evidence, the lack of a reasoned explanation weighs in favor of overturning the objections. Courts also typically consider evidence unless the objecting party can show that it could not be reduced to an admissible form at trial.” Cohen v. Gilmore, No. 19-20152 (Dec. 15, 2020) (citations omitted).

An unusual procedural path, winding through a bankruptcy proceeding, led the Fifth Circuit to review a state-court summary judgment. On the issue of the state court’s evidentiary rulings, the Court applied a federal-court approach to a standard form of Texas practice, reasoning: “The grant of these objections improperly excluded important evidence from consideration. To start, the state trial court offered no explanation as to why it granted the objections. It simply checked boxes on a form saying that the objections were sustained. Since a trial court can abuse its discretion by failing to explain the reasons for excluding evidence, the lack of a reasoned explanation weighs in favor of overturning the objections. Courts also typically consider evidence unless the objecting party can show that it could not be reduced to an admissible form at trial.” Cohen v. Gilmore, No. 19-20152 (Dec. 15, 2020) (citations omitted).

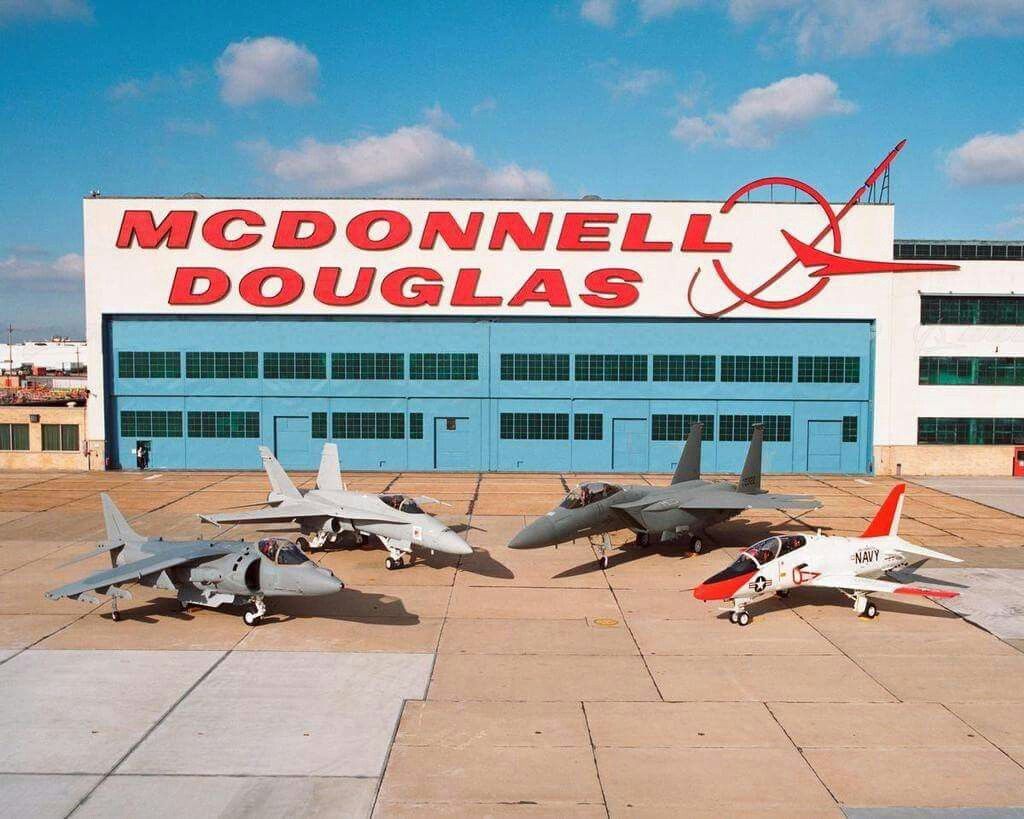

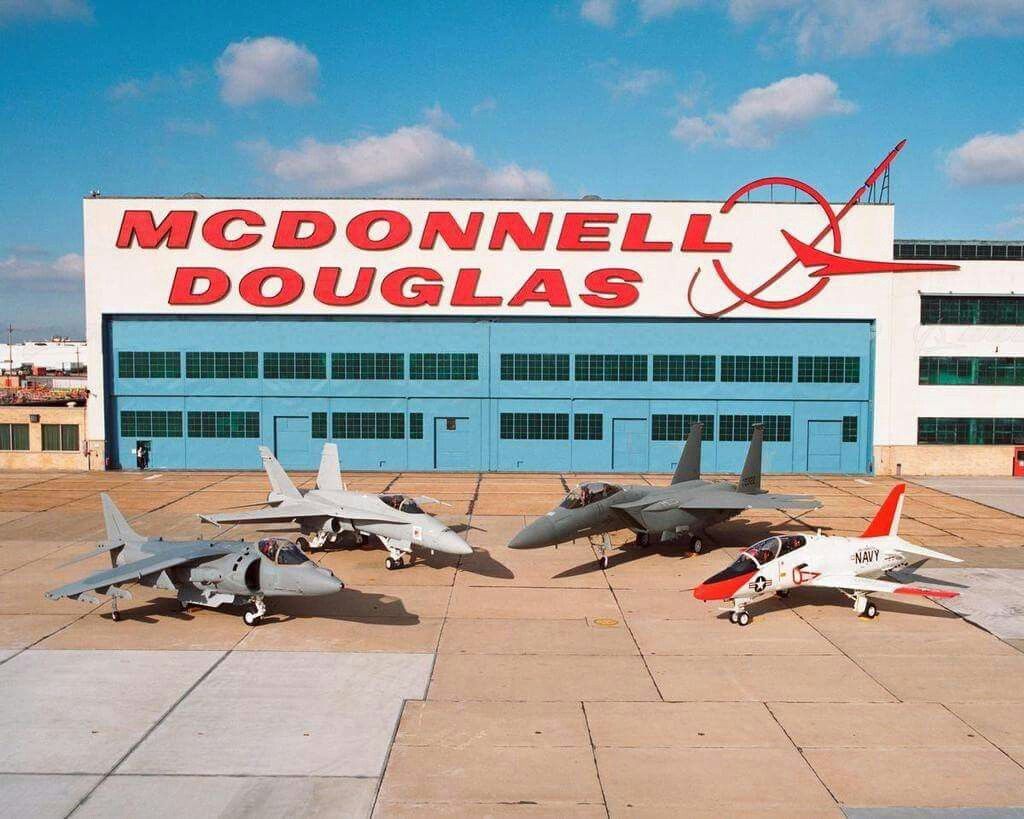

The complexities of the McDonnell-Douglass framework were not at issue in Lindsley v. TRT Holdings, Inc., No. 10-`10623 (Jan. 7, 2021), in which the Fifth Circuit found that the appellant established a prima facie case of sex discrimination:

The complexities of the McDonnell-Douglass framework were not at issue in Lindsley v. TRT Holdings, Inc., No. 10-`10623 (Jan. 7, 2021), in which the Fifth Circuit found that the appellant established a prima facie case of sex discrimination:

It is undisputed that Lindsley was paid less than her three immediate predecessors as food and beverage director of Omni Corpus Christi. As a result, she has established a prima facie case of pay discrimination, and the district court erred in concluding otherwise.

First, it is undisputed that Lindsley was paid $4,149 less than Walker and $6,149 less than Pollard. It is also undisputed that Lindsley held the same job title at the same Omni hotel as those men. What’s more, Omni agrees that Lindsley established a prima facie case of pay discrimination as to Cornelius, who held the position directly after Pollard and Walker—and there is no evidence that the position has changed since then. This establishes a prima facie case of pay discrimination.

The district court therefore erred in concluding that Lindsley failed to establish a prima facie case because she “provide[d] no evidence that her job as Food and Beverage Director was in any way similar to Pollard and Walker’s jobs, aside from the fact that they shared the same job title.” Far from failing to show that her job was “in any way similar,” Lindsley showed that she held the same position as Walker and Pollard did, at the same hotel, just a few years after they did—and that she was paid lessthan they were. No more is needed to establish a prima facie case.

Billy Joel disputed causation about starting the fire. So did the parties in Coastal Bridge Co. v. Heatec, in which the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment, holding: “Here, genuine disputes of material fact exist as to: (1) the significance of the heating pumps; (2) what

Billy Joel disputed causation about starting the fire. So did the parties in Coastal Bridge Co. v. Heatec, in which the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment, holding: “Here, genuine disputes of material fact exist as to: (1) the significance of the heating pumps; (2) what  equipment was disassembled and disposed of; (3) the origin of the subject fire and whether the inlet pipe moved; and (4) the extent of communication4 that occurred between the parties before the formal notice of the fire. These factual disputes cannot be resolved without weighing the evidence and making credibility determinations, which are matters for the factfinder.” No. 19-31030 (Nov. 6, 2020, revised).

equipment was disassembled and disposed of; (3) the origin of the subject fire and whether the inlet pipe moved; and (4) the extent of communication4 that occurred between the parties before the formal notice of the fire. These factual disputes cannot be resolved without weighing the evidence and making credibility determinations, which are matters for the factfinder.” No. 19-31030 (Nov. 6, 2020, revised).

Badgerow v. REJ Properties, Inc., No 19-30584 (Sept. 11, 2020), applying the McDonnell-Douglas burden-shifting framework, reached the issue of whether there was a fact question on pretext and concluded that there was:

Badgerow v. REJ Properties, Inc., No 19-30584 (Sept. 11, 2020), applying the McDonnell-Douglas burden-shifting framework, reached the issue of whether there was a fact question on pretext and concluded that there was:

“The timing of Badgerow’s firing is highly indicative of motive. According to Badgerow’s version of events the day she was fired, she received a call from Walters who said that he had ‘just got off the phone with Marc Cohen’ and would call her back. When Walters called Badgerow back, he asked her to travel from her office in Houma to his office in Thibodaux so that he could speak with her in person. During their in-person meeting, Walters terminated Badgerow’s employment. Thus, Badgerow’s firing occurred in the immediate aftermath of Walters being informed of Badgerow’s complaints to Cohen. And Badgerow has adduced other significant evidence of pretext. For example, although REJ states that Walters fired Badgerow due to constant complaints from her coworkers, Badgerow asserts that the only explanation he gave for her firing was that she had ‘dinged his perfect . . . record’ with Ameriprise. And Walters admits that immediately before firing Badgerow he ‘told her that Cohen had said he needed to hire a labor attorney and asked “[d]o I have to worry about you suing me?” Finally, although Walters testified that Badgerow’s coworkers had been complaining to him about her behavior for months, Walters seemed determined to keep Badgerow as one of his AFAs until his conversation with Cohen. A reasonable fact finder could infer from this evidence that REJ’s proffered reason for Badgerow’s firing was pretext for unlawful retaliation.”

(citation omitted, emphasis added).

In Six Dimensions, Inc. v. Perficient, Inc., the Fifth Circuit concluded that under California noncompete law, the parties’ “2014 Agreement” was unenforceable. A key question was whether their “2015 Agreement” was also subject to that conclusion, or whether it was separate and the arguments against it had been waived in the trial court. The Court found no waiver, concluding that the below language was insufficient notice that the plaintiff was seeking summary judgment about that contract.

In Six Dimensions, Inc. v. Perficient, Inc., the Fifth Circuit concluded that under California noncompete law, the parties’ “2014 Agreement” was unenforceable. A key question was whether their “2015 Agreement” was also subject to that conclusion, or whether it was separate and the arguments against it had been waived in the trial court. The Court found no waiver, concluding that the below language was insufficient notice that the plaintiff was seeking summary judgment about that contract.

“Defendant argues that Brading was permitted to engage in this wrongful conduct because the contract that she signed, contained a provision that is not allowed under California law. Defendant argues that even though the Amended Complaint does not accuse Brading of breaching the non-competition portion of the 2014 Agreement [Dkt 10-2], that its presence in the 2014 Agreement invalidates that agreement. Texas has no such provision. It is respectfully submitted, as asserted in the Complaint, that the law of Texas applies and as such, the 2014 Agreement is clearly breached by Brading’s undisputed conduct in violating both portions of the 2014 Agreement. Further, there is no noncompetition portion for the Termination Certification signed by Brading in June of 2015 and as such, under the law of either State, Brading is responsible for violating the 2015 Agreement.”

No. 19-20505 (Aug. 7, 2020) (emphasis added).

Hoover Panel Systems contracted with HAT Contract to design a component for office desks. The Fifth Circuit found their contract ambiguous, noting the tension between its introductory and first-numbered paragraphs. While both address confidentiality, the introduction is general and paragraph 1 describes a particular process:

Hoover Panel Systems contracted with HAT Contract to design a component for office desks. The Fifth Circuit found their contract ambiguous, noting the tension between its introductory and first-numbered paragraphs. While both address confidentiality, the introduction is general and paragraph 1 describes a particular process:

“Both parties agree that all information disclosed to the other party, such as inventions, improvements, know-how, patent applications, specifications, drawings, sample products or prototypes,[]engineering data, processes, flow diagrams, software source code, business plans, product plans, customer lists, investor lists, and any other proprietary information shall be considered confidential and shall be retained in confidence by the other party.

1. Both parties agree to keep in confidence and not use for its or others benefit all information disclosed by the other party, which the disclosing party indicates is confidential or proprietary or marked with words of similar import (hereinafter INFORMATION). Such INFORMATION shall include information disclosed orally, which is reduced to writing within five (5) days of such oral disclosure and is marked as being confidential or proprietary or marked with words of similar import.”

The Court noted “[s]everal plausible interpretations” of these paragraphs:

- Different materials. “Hoover reads the opening paragraph to apply to the prototype, the primary property the confidentiality agreement was entered into to protect. Hoover argues that the first numbered paragraph applied to other information and communications that were not obviously confidential under the opening paragraph.”

- General v. specific. “HAT reads the opening paragraph to speak generally about the content of the agreement, and the first numbered paragraph to provide the specific instructions needed to put the confidentiality agreement into effect.”

- Different procedures. “[Another possible] interpretation is that under the agreement, proprietary information is automatically confidential while all other information must be marked. The opening paragraph states that “proprietary material shall be considered confidential,” and in the first numbered paragraph, “all information . . . which the disclosing party indicates is confidential or proprietary or marked with words of similar import” is considered confidential.”

- Substance v. housekeeping. “Another plausible reading is that the opening paragraph provides the scope for all information that is confidential while the first numbered paragraph functions as a housekeeping paragraph, providing instruction on how to mark information as confidential, but not requiring labeling as a condition precedent.”

Hoover Panel Systems, Inc. v. HAT Contract, Inc., No. 19-10650 (June 17, 2020).

Katherine P. v Humana Health Plan, an ERISA dispute about hospitalization to treat an eating disorder, turned on a specific criterion: whether “[t]reatment at a less intense level of care has been unsuccessful in controlling” the disorder. The Fifth Circuit found a fact issue, noting:

Katherine P. v Humana Health Plan, an ERISA dispute about hospitalization to treat an eating disorder, turned on a specific criterion: whether “[t]reatment at a less intense level of care has been unsuccessful in controlling” the disorder. The Fifth Circuit found a fact issue, noting:

“[T]here is evidence in the administrative record that suggests Katherine P. satisfied that requirement. For example, in her last appeal Humana, Katherine P. provided a declaration describing her history of failed treatment. In it, she listed past failed treatment regimens, including outpatient treatment. Her mother likewise provided a declaration making essentially the same point. Furthermore, Katherine P.’s physicians said she was ‘unable to follow a weight gain meal plan and to abstain from symptoms of purging and restricting while she was at a lower level of care.’”

(citations omitted). The court also noted evidence cutting the other way:

Her same declaration, for example, shows that she participated in an eight-week intensive outpatient program in late 2010 that failed due to external trauma—not because the treatment was ineffective. And Humana noted that the 2010 treatment was her most recent course of treatment prior to her admittance to Oliver-Pyatt about a year and a half later. A factfinder could therefore conclude that Katherine P. failed to show that she met [the criterion].

Katherine P. v Humana Health Plan, No. 19-50276 (May 14, 2020).

The Fifth Circuit reversed a defense summary judgment in a products case in Certain Underwiters at Lloyd’s v. Axon Pressure Prods., Inc., noting:

Procedurally, a lack of explanation as to key Daubert rulings and related elements of the plaintiff’s claim, characterizing them as “pithy to the point of being incomplete.”

Procedurally, a lack of explanation as to key Daubert rulings and related elements of the plaintiff’s claim, characterizing them as “pithy to the point of being incomplete.”- Substantively, a fact issue on causation, given

conflicting testimony on (a) the handling of the relevant piece of equipment, (b) the reasons for material continuing to flow through that equipment at the time of the accident.

conflicting testimony on (a) the handling of the relevant piece of equipment, (b) the reasons for material continuing to flow through that equipment at the time of the accident.

No. 18-20453 (Feb. 21, 2020).

Gonzales cited two Texas Supreme Court cases, decided after a summary judgment against her, holding that an insurer’s payment of an appraisal award does not preclude a Texas Prompt Payment of Claims Act (“TPPCA”) claim. The Fifth Circuit found that she failed to preserve this argument in the district court. The Court noted that “a change in law . . . does not permit a party to raise an entirely new argument that could have been articulated below”–a rule that applies when a party “could have made the same ‘general argument’ to the district court, but had not done so.” As for the state of the law at the time of the summary-judgment briefing, the Court observed:

Gonzales cited two Texas Supreme Court cases, decided after a summary judgment against her, holding that an insurer’s payment of an appraisal award does not preclude a Texas Prompt Payment of Claims Act (“TPPCA”) claim. The Fifth Circuit found that she failed to preserve this argument in the district court. The Court noted that “a change in law . . . does not permit a party to raise an entirely new argument that could have been articulated below”–a rule that applies when a party “could have made the same ‘general argument’ to the district court, but had not done so.” As for the state of the law at the time of the summary-judgment briefing, the Court observed:

We recognize that several courts, including our own, had previously concluded a TPPCA claim was extinguished as a matter of law after the payment of an appraisal award. But the Supreme Court of Texas granted review in [the two relevant cases] on January 18, 2019, seven days after Allstate moved for summary judgment and thirteen days before Gonzales filed her response to the motion. This fact undermines her assertion here that she “could not have made a good faith argument in the trial court that payment of the appraisal award did not preclude her from recovering under the TPPCA as a matter of law.”

Gonzales v. Allstate Vehicle & Property Ins. Co., No. 19-40250 (Feb. 11, 2020) (emphasis added, footnote omitted).

While focused on the intricate McDonnell-Douglas burden-shifting framework (a structure described in more than one Fifth Circuit opinion as “kudzu-like“), Garcia v. Professional Contract Servcs. Inc provides general insight about creation of a genuine issue of material fact.

While focused on the intricate McDonnell-Douglas burden-shifting framework (a structure described in more than one Fifth Circuit opinion as “kudzu-like“), Garcia v. Professional Contract Servcs. Inc provides general insight about creation of a genuine issue of material fact.

As to the plaintiff’s prima facie case, all parties agreed that “proximity in time” – the passage of only 76 days between the plaintiff’s protected whistleblowing activity and termination – was sufficient to meet this burden.

As to pretext, while temporal proximity alone is not enough, the Fifth Circuit found a genuine issue of fact when the plaintiff pointed to: “(1) temporal proximity between his protected activity and his firing; (2) his dispute of the facts leading up to his termination; (3) a similarly situated employee who was not terminated for similar conduct; (4) harassment from his supervisor after the company knew of his protected whistleblowing conduct; (5) the ultimate stated reason for the company’s termination of [plaintiff] had been known to the compan y for years; and (6) the company stood to lose millions of dollars if its conduct was discovered.” The Court also disagreed with the district court about whether the “similarly situated” employee identified by the plaintiff qualified as such, noting that while they worked in different divisions: “Rodas and Garcia had identical jobs, reported to the same people, had a similar history of infractions, and both made mistakes overseeing Job 560.” No. 18-50144 (Sept. 11, 2019).

y for years; and (6) the company stood to lose millions of dollars if its conduct was discovered.” The Court also disagreed with the district court about whether the “similarly situated” employee identified by the plaintiff qualified as such, noting that while they worked in different divisions: “Rodas and Garcia had identical jobs, reported to the same people, had a similar history of infractions, and both made mistakes overseeing Job 560.” No. 18-50144 (Sept. 11, 2019).

In Simmons v. Pacific Bells LLC, the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment against a Taco Bell employee who claimed he was retaliated against for going to jury duty. In particular –

He raised specific facts indicating that his termination for tardiness may have been pretextual. First, Simmons was tardy less often than other coworkers, yet those coworkers were not terminated and did not suffer adverse employment action. Second, he was never once warned about his tardiness prior to his termination. Third, Simmons demonstrated that some of his tardiness resulted from Pacific Bells’s business practices. Fourth, he was terminated immediately following his jury service. Fifth, the individual who told Simmons to lie recommended his termination and was present for it. Sixth, the individual who terminated Simmons stated in an email that she had “several different routes I can go with his termination. . . . I want to focus on [his] excessive tardiness.” In sum, the timing of Simmons’s termination, combined with the arguably pretextual rationale for his firing, could lead a reasonable jury to conclude that he was fired as a result of his refusal to lie to avoid jury service.

The Court declined to address a related issue about the scope of the “interested witness” doctrine in summary-judgment practice. No. 19-60001 (Sept. 27, 2019) (unpublished).

An accounting firm successfully defended against a malpractice claim by relying on Mississippi’s “minutes rule,” under which “Mississippi courts will not give legal effect to a contract with a public board unless the board’s approval of the contract is reflected in its minutes.” After losing a summary judgment, the plaintiff (a county hospital) “attempted to submit additional evidence into the record to prove the existence of a professional relationship with Horne—namely, minutes from the board’s regular session meetings on January 19, 2011 and March 16, 2011, as well as minutes from the board’s executive session meetings. . . . The Medical Center admitted, however, that this evidence was in fact not new at all—the Center had access to its own minutes throughout the proceedings. It nevertheless sought to excuse its tardiness on the ground that the minutes became relevant only when the district court granted summary judgment to Horne.” (emphasis added). The district court rejected that explanation, and so did the Fifth Circuit. Lefoldt v. Horne LLP, No. 18-60581 (Sept. 6, 2019).

An accounting firm successfully defended against a malpractice claim by relying on Mississippi’s “minutes rule,” under which “Mississippi courts will not give legal effect to a contract with a public board unless the board’s approval of the contract is reflected in its minutes.” After losing a summary judgment, the plaintiff (a county hospital) “attempted to submit additional evidence into the record to prove the existence of a professional relationship with Horne—namely, minutes from the board’s regular session meetings on January 19, 2011 and March 16, 2011, as well as minutes from the board’s executive session meetings. . . . The Medical Center admitted, however, that this evidence was in fact not new at all—the Center had access to its own minutes throughout the proceedings. It nevertheless sought to excuse its tardiness on the ground that the minutes became relevant only when the district court granted summary judgment to Horne.” (emphasis added). The district court rejected that explanation, and so did the Fifth Circuit. Lefoldt v. Horne LLP, No. 18-60581 (Sept. 6, 2019).

The Fifth Circuit revised its original opinion in SEC v. Arcturus Corp., reaching the same result (reversal of a summary judgment for the SEC about whether certain investment contracts were securities), while adding significant factual and legal detail about the sophistication of the relevant investors – the issue on which the Court found summary judgment to have been inappropriate. SEC v. Arcturus Corp. (revised), No. 17-10503.

The Fifth Circuit revised its original opinion in SEC v. Arcturus Corp., reaching the same result (reversal of a summary judgment for the SEC about whether certain investment contracts were securities), while adding significant factual and legal detail about the sophistication of the relevant investors – the issue on which the Court found summary judgment to have been inappropriate. SEC v. Arcturus Corp. (revised), No. 17-10503.

Hira, a guarantor, argued that the lender’s calculation of the amount due should not have been accepted as a basis for summary judgment against her. The Fifth Circuit disagreed:

Hira, a guarantor, argued that the lender’s calculation of the amount due should not have been accepted as a basis for summary judgment against her. The Fifth Circuit disagreed:

Hira never proposed her own calculations, a step she was required to take by Texas law and the district court’s summary judgment order. RBC Real Estate Fin. v. Partners Land Dev., Ltd.543 F. App’x 477, 480 (5th Cir. 2013) (per curiam) (unpublished) (upholding a grant of summary judgment because the appellants “did not provide any controverting summary judgment evidence to the district court”); 8920 Corp. v. Alief Alamo Bank, 722 S.W.2d 718, 720 (Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.] 1986, writ ref’d n.r.e.) (granting a motion for summary judgement because the appellants “presented no controverting affidavits that could raise a fact issue as to appellee’s method of computation and the accuracy of its figures.”). Without providing a competing calculation, Hira failed to raise a genuine issue of material fact.

Pacific Premier Bank v. Hira, No. 18-10611 (April 15, 2019, unpublished).

The panel majority in Waste Management, Inc. v. River Birch, Inc.reversed a defense summary judgment in a civil RICO case, on the question whether an alleged bribe was the cause of an action by the disgraced former mayor Ray Nagin. The opinion detailed the circumstantial evidence both about the alleged bribe and its alleged effect, and found that a jury question had been presented: “Noting that It is rare in public bribery cases that there is definitive ‘smoking gun’ evidence to show a payment was made to an official to influence the official to perform some act—and there is no such evidence here. It is critical in cases such as this that inferences from circumstantial evidence about intent and motives about which reasonable minds could differ be sorted out by the jury.” (footnotes omitted). The dissent observed: “I don’t like granting summary judgment to campaign-finance violators. Nor do I like giving the benefit of the doubt to disgraced ex-government officials. But, in the absence of evidence, it’s what the law commands,” relying primarily on the Supreme Court’s Matsushita summary-judgment opinion. (Judge Davis wrote the majority opinion joined by Judge Costa; Judge Oldham dissented). A brief opinion on rehearing noted that the parties had not cited Matsushita so the court “therefore decline[s] to consider that case now.”

The panel majority in Waste Management, Inc. v. River Birch, Inc.reversed a defense summary judgment in a civil RICO case, on the question whether an alleged bribe was the cause of an action by the disgraced former mayor Ray Nagin. The opinion detailed the circumstantial evidence both about the alleged bribe and its alleged effect, and found that a jury question had been presented: “Noting that It is rare in public bribery cases that there is definitive ‘smoking gun’ evidence to show a payment was made to an official to influence the official to perform some act—and there is no such evidence here. It is critical in cases such as this that inferences from circumstantial evidence about intent and motives about which reasonable minds could differ be sorted out by the jury.” (footnotes omitted). The dissent observed: “I don’t like granting summary judgment to campaign-finance violators. Nor do I like giving the benefit of the doubt to disgraced ex-government officials. But, in the absence of evidence, it’s what the law commands,” relying primarily on the Supreme Court’s Matsushita summary-judgment opinion. (Judge Davis wrote the majority opinion joined by Judge Costa; Judge Oldham dissented). A brief opinion on rehearing noted that the parties had not cited Matsushita so the court “therefore decline[s] to consider that case now.”

Wease established ambiguity in two as pects of a deed of trust. With respect to when a servicer could pay the borrower’s property taxes by the servicer, the key provision used the fact-specific phrase “reasonable or appropriate”; other provisions both suggested that the power was limited to back taxes, but also that it could be made “at any time.” Accordingly, “Wease was entitled to proceed to trial on his claim that Ocwen breached the contract by paying his 2010 taxes before the tax lien attached and before they became delinquent.” This analysis led to finding a triable fact issue as to whether Ocwen provided adequate notice of its actions. Wease v. Ocwen Loan Servicing, No. 17-01574 (Jan. 4, 2019). A revised opinion eliminated some statements about tax liens and when they took effect.

pects of a deed of trust. With respect to when a servicer could pay the borrower’s property taxes by the servicer, the key provision used the fact-specific phrase “reasonable or appropriate”; other provisions both suggested that the power was limited to back taxes, but also that it could be made “at any time.” Accordingly, “Wease was entitled to proceed to trial on his claim that Ocwen breached the contract by paying his 2010 taxes before the tax lien attached and before they became delinquent.” This analysis led to finding a triable fact issue as to whether Ocwen provided adequate notice of its actions. Wease v. Ocwen Loan Servicing, No. 17-01574 (Jan. 4, 2019). A revised opinion eliminated some statements about tax liens and when they took effect.

Nall, who worked for BNSF as a trainman, suffered from Parkinson’s disease, and sued BNSF for disability discrimination. The panel majority noted that BNSF had provided different descriptions of a trainman’s duties at different times, and that a key BNSF witness agreed with a version that helped Nall’s position. It thus found a fact issue, specifically described as follows:

Nall, who worked for BNSF as a trainman, suffered from Parkinson’s disease, and sued BNSF for disability discrimination. The panel majority noted that BNSF had provided different descriptions of a trainman’s duties at different times, and that a key BNSF witness agreed with a version that helped Nall’s position. It thus found a fact issue, specifically described as follows:

We emphasize that our inquiry on the issue of objective reasonableness does not ask whether BNSF’s conclusion that Nall could not perform his job duties safely was a reasonable medical judgment. Instead, we ask whether BNSF actually exercised that judgment. In other words, the question on appeal is not whether it was reasonable for BNSF to conclude that Parkinson’s disease symptoms prevented Nall from safely performing his duties; the question is whether BNSF came to that conclusion via a reasonable process that was not, as Nall alleges, manipulated midstream to achieve BNSF’s desired result of disqualifying him. More precisely, the question is whether there is any evidence in the record which, if believed, would be sufficient to support a jury finding.

(emphasis in original). A dissent observed: “There is no basis for imposing liability under the ADA based on process concerns alone. There is liability only if the employer’s determination of a direct threat is objectively unreasonable.” A concurrence noted the “kudzu-like creep” of the McDonnell-Douglas burden-shifting framework, and as to dissent, observed that it “reminds me of the baseball player who said, ‘They should move back first base a step to eliminate all those close plays.'” Nall v. BNSF Railway Co., No. 17-20113 (Dec. 27, 2018).

(emphasis in original). A dissent observed: “There is no basis for imposing liability under the ADA based on process concerns alone. There is liability only if the employer’s determination of a direct threat is objectively unreasonable.” A concurrence noted the “kudzu-like creep” of the McDonnell-Douglas burden-shifting framework, and as to dissent, observed that it “reminds me of the baseball player who said, ‘They should move back first base a step to eliminate all those close plays.'” Nall v. BNSF Railway Co., No. 17-20113 (Dec. 27, 2018).

In Kiewit Offshore v. Dresser-Rand, the Fifth Circuit affirmed a summary judgment for the plaintiff in a large construction matter; as the final point addressed, the Court observed: “Dresser-Rand contends, for the first time on appeal, that Kiewit submitted insufficient, conclusory summaries of the work reflected in Invoices DR-04b, 05, and 06, preventing the district court from verifying the total amount of damages Kiewit claimed. Dresser-Rand failed to raise this argument below, and we therefore decline to consider it here.” The Court also noted that “it was undisputed that the invoices accurately reflected actual costs incurred . . . for work performed and accepted . . . .” It is a fair question whether the same result would obtain under Texas state practice, which among other matters distinguishes between “substantive” and “form” objections to summary judgment affidavits – “form” issues requiring objection, but not substantive ones. See Seim v. Allstate Texas Lloyds, No. 17-0488, 2018 WL 3189568, at *3 (Tex. June 29, 2018) (per curiam).

In Kiewit Offshore v. Dresser-Rand, the Fifth Circuit affirmed a summary judgment for the plaintiff in a large construction matter; as the final point addressed, the Court observed: “Dresser-Rand contends, for the first time on appeal, that Kiewit submitted insufficient, conclusory summaries of the work reflected in Invoices DR-04b, 05, and 06, preventing the district court from verifying the total amount of damages Kiewit claimed. Dresser-Rand failed to raise this argument below, and we therefore decline to consider it here.” The Court also noted that “it was undisputed that the invoices accurately reflected actual costs incurred . . . for work performed and accepted . . . .” It is a fair question whether the same result would obtain under Texas state practice, which among other matters distinguishes between “substantive” and “form” objections to summary judgment affidavits – “form” issues requiring objection, but not substantive ones. See Seim v. Allstate Texas Lloyds, No. 17-0488, 2018 WL 3189568, at *3 (Tex. June 29, 2018) (per curiam).

While cleaning ventilation equipment at the L’Auberge Casino in Lake Charles, Renwick fell from a defective ladder and later sued the property owner for his injuries. The Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment for the defense, noting “that it is th[e] combination of evidence–[Defendant’s] control of work-site access, its specific instructions about how to reach the vents, its rejection of an alternate access route, and the dispute over who provided the access ladder–that creates a jury issue on operational control.” (emphasis in original0 The Court reminded: “To be sure, a fact finder could ultimately reach a different conclusion. All we decide is that the evidence –viewed, as it must be, in the light most favorable to Renwick– would permit a reasonable trier of fact to resolve the operational control issue either way, and that the district court therefore erred in granting summary judgment.” Renwick v. PNK Lake Charles LLC, No. 17-30767 (Aug. 27, 2018).

While cleaning ventilation equipment at the L’Auberge Casino in Lake Charles, Renwick fell from a defective ladder and later sued the property owner for his injuries. The Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment for the defense, noting “that it is th[e] combination of evidence–[Defendant’s] control of work-site access, its specific instructions about how to reach the vents, its rejection of an alternate access route, and the dispute over who provided the access ladder–that creates a jury issue on operational control.” (emphasis in original0 The Court reminded: “To be sure, a fact finder could ultimately reach a different conclusion. All we decide is that the evidence –viewed, as it must be, in the light most favorable to Renwick– would permit a reasonable trier of fact to resolve the operational control issue either way, and that the district court therefore erred in granting summary judgment.” Renwick v. PNK Lake Charles LLC, No. 17-30767 (Aug. 27, 2018).

The “equal inference” rule has played an important role in Texas law about sufficiency of the evidence, especially after the memorable hypothetical in City of Keller v. Wilson, 168 S.W.3d 802, 814 (Tex. 2005): “Thus, for example, one might infer from cart tracks in spilled macaroni salad that it had been on the floor a long time, but one might also infer the opposite—that a sloppy shopper recently did both.” But that rule did not control in a slip-and-fall case involving the residue from an “autoscrubber” (right). The Fifth Circuit reasoned: “[Plaintiff’s] position is that the [security] video and Wal-Mart policies together suggest that (a) Wal-Mart used the machine to place slippery liquid on the floor, (b) the liquid was likely to collect in low-lying areas, (c) the machine paused over a low-lying area, (d) no Wal-Mart personnel checked for or took the requisite steps to remove it, and (e) [Plaintiff] slipped just where the machine had paused. This plausibly suggests the spill came from the auto-scrubber.” Garcia v. Wal-Mart, No. 17-20429 (June 18, 2018).

The “equal inference” rule has played an important role in Texas law about sufficiency of the evidence, especially after the memorable hypothetical in City of Keller v. Wilson, 168 S.W.3d 802, 814 (Tex. 2005): “Thus, for example, one might infer from cart tracks in spilled macaroni salad that it had been on the floor a long time, but one might also infer the opposite—that a sloppy shopper recently did both.” But that rule did not control in a slip-and-fall case involving the residue from an “autoscrubber” (right). The Fifth Circuit reasoned: “[Plaintiff’s] position is that the [security] video and Wal-Mart policies together suggest that (a) Wal-Mart used the machine to place slippery liquid on the floor, (b) the liquid was likely to collect in low-lying areas, (c) the machine paused over a low-lying area, (d) no Wal-Mart personnel checked for or took the requisite steps to remove it, and (e) [Plaintiff] slipped just where the machine had paused. This plausibly suggests the spill came from the auto-scrubber.” Garcia v. Wal-Mart, No. 17-20429 (June 18, 2018).

A photographer sued a business for using his copyrighted pictures. The defendant assert its licensing rights as a defense; specifically, as a sublicensee of the industry group that obtained a license from the photographer. The Fifth Circuit observed: “The right to bring a copyright infringement action comes from federal copyright law,” which is “a separate question from whether [the defendant] can prove (under state law)

A photographer sued a business for using his copyrighted pictures. The defendant assert its licensing rights as a defense; specifically, as a sublicensee of the industry group that obtained a license from the photographer. The Fifth Circuit observed: “The right to bring a copyright infringement action comes from federal copyright law,” which is “a separate question from whether [the defendant] can prove (under state law)  that it has a meritorious license defense. Based on that observation, the Court concluded that the district court had incorrectly conflated the plaintiff’s right to sue on the license under state law with its standing to raise copyright claims under federal law, and reversed a summary judgment for the defendant. As to the scope of the sublicense, the Court found a triable fact issue presented by an affiant’s assertion about the duration of that license, which was not completely supported by the dates on the documents submitted with that affidavit. Stross v. Redfin Corp., No. 17-50046 (April 9, 2018) (While issued per curiam, certain turns of phrase in the opinion suggest the handiwork of newly-arrived Judge Willett, who was on the panel.)

that it has a meritorious license defense. Based on that observation, the Court concluded that the district court had incorrectly conflated the plaintiff’s right to sue on the license under state law with its standing to raise copyright claims under federal law, and reversed a summary judgment for the defendant. As to the scope of the sublicense, the Court found a triable fact issue presented by an affiant’s assertion about the duration of that license, which was not completely supported by the dates on the documents submitted with that affidavit. Stross v. Redfin Corp., No. 17-50046 (April 9, 2018) (While issued per curiam, certain turns of phrase in the opinion suggest the handiwork of newly-arrived Judge Willett, who was on the panel.)

Castrellon sought to enforce a loan modification agreement; the defendants asserted a mutual mistake about Castrellon’s ability to sign the agreement without also obtaining the agreement of her ex-husband. Noting that she could be left empty-handed otherwise, the Fifth Circuit found a fact issue on that defense: “[T]he mere fact that the agreement may ultimately leave [her] empty-handed does not compel the conclusion that there was a mutual mistake . . . . [N]onetheless, it does support an inference that the parties mistakenly believed they could modify the loan agreement without [him] – an inference that we are required to draw at this juncture.” Castrellon v. Ocwen Loan Servicing, No. 17-40193 (Feb. 21, 2018, unpublished).

Castrellon sought to enforce a loan modification agreement; the defendants asserted a mutual mistake about Castrellon’s ability to sign the agreement without also obtaining the agreement of her ex-husband. Noting that she could be left empty-handed otherwise, the Fifth Circuit found a fact issue on that defense: “[T]he mere fact that the agreement may ultimately leave [her] empty-handed does not compel the conclusion that there was a mutual mistake . . . . [N]onetheless, it does support an inference that the parties mistakenly believed they could modify the loan agreement without [him] – an inference that we are required to draw at this juncture.” Castrellon v. Ocwen Loan Servicing, No. 17-40193 (Feb. 21, 2018, unpublished).

Cox v. Provident Life involved a dispute about the cause of the plaintiff’s knee problems: “Under the policies, Cox is entitled to receive disability benefits for life if, and only if, his disability resulted from injury rather sickness.” The record showed that:

Cox v. Provident Life involved a dispute about the cause of the plaintiff’s knee problems: “Under the policies, Cox is entitled to receive disability benefits for life if, and only if, his disability resulted from injury rather sickness.” The record showed that:

Shelton, the treating physician, gave deposition testimony that, ‘to a reasonable degree of medical probability,’ ‘the trauma to [Cox’s] left knee when he fell in the hole on December 26, 2010, caused or contributed to the cause of his disability.’ In the same deposition, Shelton reaffirmed that ‘[e]ven though [Cox] may have had some pre-existing arthritis or chondromalacia,’ the injury ‘contributed to and caused part of [Cox’s] disability.’ The district court never grappled with these unequivocal

statements, instead embracing contrary evidence presented by Provident suggesting Cox’s injury did not accelerate his arthritis. That was error. This is a classic ‘battle of the experts,’ the winner of which must be decided by a jury.

No. 16-60831 (revised Jan. 2, 2018).

A longshoreman died after stepping through a hole on an oil platform. The district court granted summary judgment, finding no fact issue about the “open and obvious” nature of the hole – a necessary element for recovery under the LHWCA. The Fifth Circuit reversed, finding conflicting testimony on the issue, and commenting on pictures of the scene (right): “True, the pictures taken directly over the hole, as one might expect, depict a visible opening. But the pictures taken from an angle–similar to the point of view of a person approaching the hole–depict the way in which the platform’s grating, in [a witness’s] words, can ‘play tricks on your eyes’ and make the opening difficult to see.” The Court reminded that even though the case would be tried to the bench: “Judicial efficiency is a noble goal, to be sure. But when an evidentiary record contains a material factual dispute (as this one does), we simply cannot bypass the role of the fact-finder, whoever that may be.” Manson Gulf LLC v. Modern American Recycling Service, Inc., No. 17-30007 (Dec. 18, 2017).

A longshoreman died after stepping through a hole on an oil platform. The district court granted summary judgment, finding no fact issue about the “open and obvious” nature of the hole – a necessary element for recovery under the LHWCA. The Fifth Circuit reversed, finding conflicting testimony on the issue, and commenting on pictures of the scene (right): “True, the pictures taken directly over the hole, as one might expect, depict a visible opening. But the pictures taken from an angle–similar to the point of view of a person approaching the hole–depict the way in which the platform’s grating, in [a witness’s] words, can ‘play tricks on your eyes’ and make the opening difficult to see.” The Court reminded that even though the case would be tried to the bench: “Judicial efficiency is a noble goal, to be sure. But when an evidentiary record contains a material factual dispute (as this one does), we simply cannot bypass the role of the fact-finder, whoever that may be.” Manson Gulf LLC v. Modern American Recycling Service, Inc., No. 17-30007 (Dec. 18, 2017).

Griffin v. Hess Corp. involved a summary judgment for the defense on the statute of limitations, based on deposition admissions about the plaintiffs’ knowledge of relevant facts. Their testimony differed in response to the summary judgment motion, and the Fifth Circuit agreed that the different testimony did not raise a sufficient issue of fact: “Appellants’ explanation—that the deposition testimony was only meant to speak of what they knew in the present tense and not to their knowledge prior to the actual filing of the complaint—does not remedy or sufficiently explain the contradiction in light of the repeated questions about the particular date certain events took place concerning their royalty claims accruing from the Property. The deposition questions, as Appellees counsel repeatedly indicated and Appellants affirmed, related to the Property and royalties accruing from the production of oil on the Property.” No. 17-30165 (Nov. 3, 2017, unpublished).

Griffin v. Hess Corp. involved a summary judgment for the defense on the statute of limitations, based on deposition admissions about the plaintiffs’ knowledge of relevant facts. Their testimony differed in response to the summary judgment motion, and the Fifth Circuit agreed that the different testimony did not raise a sufficient issue of fact: “Appellants’ explanation—that the deposition testimony was only meant to speak of what they knew in the present tense and not to their knowledge prior to the actual filing of the complaint—does not remedy or sufficiently explain the contradiction in light of the repeated questions about the particular date certain events took place concerning their royalty claims accruing from the Property. The deposition questions, as Appellees counsel repeatedly indicated and Appellants affirmed, related to the Property and royalties accruing from the production of oil on the Property.” No. 17-30165 (Nov. 3, 2017, unpublished).

Wildman sued about a Medtronic device implanted in his back to relieve pain, contending that the device did not last as long as the company warranted. Medtronic argued that this claim was preempted by federal law. The question, then, is whether that warranty claim imposes requirements “different from” those of the FDA – put differently, whether it would “undermine FDA regulation or reinforce it.” The Fifth Circuit found that it was not preempted, reasoning that Medtronic made a warranty of “the longevity of the entire [d]evice,” which “goes beyond what the FDA evaluated in its approval process,” as that procees focused specifically on the testing of batteries. The Court thus reversed a summary judgment for Medtronic and remanded, noting that on remand the district could consider “another argument challenging the plausibility of Wildman’s claim: that he did not allege reliance on the warranty.” Wildman v. Medtronic, Inc., No. 17-50010 (Oct. 31, 2017).

Wildman sued about a Medtronic device implanted in his back to relieve pain, contending that the device did not last as long as the company warranted. Medtronic argued that this claim was preempted by federal law. The question, then, is whether that warranty claim imposes requirements “different from” those of the FDA – put differently, whether it would “undermine FDA regulation or reinforce it.” The Fifth Circuit found that it was not preempted, reasoning that Medtronic made a warranty of “the longevity of the entire [d]evice,” which “goes beyond what the FDA evaluated in its approval process,” as that procees focused specifically on the testing of batteries. The Court thus reversed a summary judgment for Medtronic and remanded, noting that on remand the district could consider “another argument challenging the plausibility of Wildman’s claim: that he did not allege reliance on the warranty.” Wildman v. Medtronic, Inc., No. 17-50010 (Oct. 31, 2017).

The concept of a “genuine issue of material fact” is largely unquantifiable, but occasionally a case does set a quantitative landmark. In Shirey v. Wal-Mart Stores Texas, LLC, the Fifth Circuit addressed a personal injury claim asserting that a Wal-Mart store had constructive notice of a grape on the floor, holding:

The concept of a “genuine issue of material fact” is largely unquantifiable, but occasionally a case does set a quantitative landmark. In Shirey v. Wal-Mart Stores Texas, LLC, the Fifth Circuit addressed a personal injury claim asserting that a Wal-Mart store had constructive notice of a grape on the floor, holding:

Photographic and video evidence demonstrate that the grape was, as the district court noted, almost invisible on the off-white floor. The evidence also fails to establish that any Wal-Mart employee was in proximity to the grape for a sufficient period of time. The few seconds during which the employee passed by the grape did not provide an objectively reasonable opportunity for him to see it, notwithstanding his employer’s policy that he perform visual “sweeps” for hazards. Under these circumstances, the seventeen minutes during which the inconspicuous grape was on the floor did not afford Wal-Mart a reasonable time to discover and remove the hazard.

No. 17-20298 (Oct. 30, 2017, unpublished) (emphasis added).

In a reminder of the surprising complexity that can surround litigation about a party’s standing to bring a claim, in Intrepid Ship Mgmnt v. Malin Int’l Ship Repair, the Fifth Circuit noted a source of potential confusion about the applicable procedure: “Although a dismissal for lack of standing is appropriately judged under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(1), which allows a court to make limited findings of fact, the parties have argued this case under the standards applicable to ordinary summary judgment motions. Compare Lane v. Halliburton, 529 F.3d 548, 557 (5th Cir. 2008) (explaining that the district court can resolve disputed facts as necessary to decide a challenge to subject atter jurisdiction), withInt’l Marine LLC v. Integrity Fisheries, Inc., 860 F.3d 754, 759 (5th Cir. 2017) (applying de novo review to summary judgment cases, explaining that “[s]ummary judgment is appropriate when ‘there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact.’”)”. No. 16-41074 (Oct. 11, 2017) (unpublished).

In a reminder of the surprising complexity that can surround litigation about a party’s standing to bring a claim, in Intrepid Ship Mgmnt v. Malin Int’l Ship Repair, the Fifth Circuit noted a source of potential confusion about the applicable procedure: “Although a dismissal for lack of standing is appropriately judged under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(1), which allows a court to make limited findings of fact, the parties have argued this case under the standards applicable to ordinary summary judgment motions. Compare Lane v. Halliburton, 529 F.3d 548, 557 (5th Cir. 2008) (explaining that the district court can resolve disputed facts as necessary to decide a challenge to subject atter jurisdiction), withInt’l Marine LLC v. Integrity Fisheries, Inc., 860 F.3d 754, 759 (5th Cir. 2017) (applying de novo review to summary judgment cases, explaining that “[s]ummary judgment is appropriate when ‘there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact.’”)”. No. 16-41074 (Oct. 11, 2017) (unpublished).

In Hills v. Entergy Operations, Inc., a case about overtime pay for security guards, the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment based upon a conclusion about two guards’ lack of damage. While the Court’s holding was based upon technical issues of employment law, its underlying reasoning is of broader applicability: “We reverse the district court’s summary judgment that the fluctuating workweek method applies here as a matter of law. The underlying factual issue upon which the applicabilty of that method is predicated, what the employees clearly understood, should be decided at trial in due course.” No. 16-30924 (Aug. 4, 2017). Also, in a ruling of general interest about administrative law, the Court declined to follow an interpretive letter by the Department of Labor.

In Hills v. Entergy Operations, Inc., a case about overtime pay for security guards, the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment based upon a conclusion about two guards’ lack of damage. While the Court’s holding was based upon technical issues of employment law, its underlying reasoning is of broader applicability: “We reverse the district court’s summary judgment that the fluctuating workweek method applies here as a matter of law. The underlying factual issue upon which the applicabilty of that method is predicated, what the employees clearly understood, should be decided at trial in due course.” No. 16-30924 (Aug. 4, 2017). Also, in a ruling of general interest about administrative law, the Court declined to follow an interpretive letter by the Department of Labor.

McCarty fell outside a restaurant kitchen; her subsequent lawsuit against the restaurant for premises liability failed for lack of evidence. The Fifth Circuit distinguished the Texas appellate authority she cited by observing: “The evidence in each of these cases provided context for how long the hazardous condition had existed, in the form of either a discrete and readily documented antecedent event (e.g., a rainfall) or an attribute of the hazard (e.g., a puddle’s size, from which the jury could reasonably infer how long the puddle had been growing). In this case, by contrast, no evidence would permit the jury to trace the alleged slip risk to a particular antecedent event. Nor could a jury infer from any attributes of the alleged hazard that it had been growing over any length of time.” McCarty v. Hillstone Restaurant Group, No. 16-11519 (July 18, 2017).

McCarty fell outside a restaurant kitchen; her subsequent lawsuit against the restaurant for premises liability failed for lack of evidence. The Fifth Circuit distinguished the Texas appellate authority she cited by observing: “The evidence in each of these cases provided context for how long the hazardous condition had existed, in the form of either a discrete and readily documented antecedent event (e.g., a rainfall) or an attribute of the hazard (e.g., a puddle’s size, from which the jury could reasonably infer how long the puddle had been growing). In this case, by contrast, no evidence would permit the jury to trace the alleged slip risk to a particular antecedent event. Nor could a jury infer from any attributes of the alleged hazard that it had been growing over any length of time.” McCarty v. Hillstone Restaurant Group, No. 16-11519 (July 18, 2017).

Duncan, a Wal-Mart employee, slipped on a mat near an ice freezer in the store. She sued for her injuries and the Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for the defense, noting several ways in which her proof of a dangerous condition was lacking: “In Duncan’s deposition—the only evidence she and Johnson submitted in support of their claim—she repeatedly explained that she did not know how water developed under the mat on which she slipped. Duncan couldn’t say whether water had ‘somehow leaked or spilled underneath the mat’ or whether ‘something on top of the mat . . . leaked through it.’ No one at Wal-Mart told her that they knew there was water in that area before she fell, and she didn’t know whether water had ever accumulated in that area before. Duncan also said that in the four years she worked at Wal-Mart, she had never heard of the Reddy Ice machine leaking, even though she knew other appliances, like the ‘Coke machine,’ leaked. ” Duncan v. Wal-Mart Louisiana LLC, No. 16-31223 (July 14, 2017).

Lee sued for his injuries from a fall on the M/V BALTY (right). In resolving the defendant’s summary judgment motion, “[t]he district court dismissed Captain Jamison’s report solely because it was not sworn without considering Lee’s argument that Captain Jamison would testify to those opinions at trial and without determining whether such opinions, as testified to at trial, would be admissible.” The Ffith Circuit remanded for reconsideration in light of a 2010 amendment to Fed. R. Civ. P. 56 that says (as summarized by Moore’s Federal Practice): “Although the substance or content of the evidence submitted to support or dispute a fact on summary judgment must be admissible . . . , the material may be presented in a form that would not, in itself, be admissible at trial.” Lee v. Offshore Logistical No. 16-31049 (revised July 5, 2017).

Lee sued for his injuries from a fall on the M/V BALTY (right). In resolving the defendant’s summary judgment motion, “[t]he district court dismissed Captain Jamison’s report solely because it was not sworn without considering Lee’s argument that Captain Jamison would testify to those opinions at trial and without determining whether such opinions, as testified to at trial, would be admissible.” The Ffith Circuit remanded for reconsideration in light of a 2010 amendment to Fed. R. Civ. P. 56 that says (as summarized by Moore’s Federal Practice): “Although the substance or content of the evidence submitted to support or dispute a fact on summary judgment must be admissible . . . , the material may be presented in a form that would not, in itself, be admissible at trial.” Lee v. Offshore Logistical No. 16-31049 (revised July 5, 2017).

In Austin v. Kroger Texas LP, the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment for the defendant in a slip-and-fall case. On the merits, among other holdings of general interest, the Court noted:

In Austin v. Kroger Texas LP, the Fifth Circuit reversed a summary judgment for the defendant in a slip-and-fall case. On the merits, among other holdings of general interest, the Court noted:

- “[A] janitor with fifteen years’ experience is competent to testify about the effectiveness of cleaning products and methods.”;

- When coupled with evidence from “Kroger’s handbook” and the manager’s testimony about “the safety practice at the store,” the plaintiff raised a fact issue;

- “[T]he fact that [Plaintiff] had successfuly cleaned a much smaller spill . . . with a dry mop does not conclusively demonstrate that Spill Magic was not necessary for [him] to safely clean a much larger and more serious spill.”

Procedurally, the Court instructed that the trial court should proceed under “the more flexible Rule 54(b)” on remand rather than “the heightened standard of Rule 59(e),” asking that it “construe the procedural rules with a preference toward resolving the case on the merits and avoiding any dismissal based on a technicality.” No. 16-10502 (April 14, 2017).

Several crawfishermen sued about the effects of canal dredging on the Atchafalaya Basin fisheries. As to one defendant company, the Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment in its favor, reviewing each of the documents cited by plaintiffs and finding that none raised a genuine issue of material fact as to actual dredging activity by that company, on the pipelines at issue in this case. As to another, the Court reversed on procedural grounds, finding that the district court should have considered a deposition transcript and responses to requests for admissions offered by the plaintiffs when (1) their proffer had a foundation in the terms of the case management order, (2) the evidence was probative, and (3) it was information obtained from that defendant. In re Louisiana Crawfish Producers, No. 16-30353 (March 28, 2017). (The opinion notes that crawfish are known by several other names, including “yabbies,” a tidbit that was not known to this author.)

Several crawfishermen sued about the effects of canal dredging on the Atchafalaya Basin fisheries. As to one defendant company, the Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment in its favor, reviewing each of the documents cited by plaintiffs and finding that none raised a genuine issue of material fact as to actual dredging activity by that company, on the pipelines at issue in this case. As to another, the Court reversed on procedural grounds, finding that the district court should have considered a deposition transcript and responses to requests for admissions offered by the plaintiffs when (1) their proffer had a foundation in the terms of the case management order, (2) the evidence was probative, and (3) it was information obtained from that defendant. In re Louisiana Crawfish Producers, No. 16-30353 (March 28, 2017). (The opinion notes that crawfish are known by several other names, including “yabbies,” a tidbit that was not known to this author.)

Defendants moved for summary judgment, on the ground of qualified immunity, in a case arising from a fatal police shooting. The district court “disregarded the testimony of [Officer] Copeland and two eyewitnesses, finding that because there was ‘no video evidence of the actual shooting[,]’ the ‘testimony of Copeland, the eyewitness, and the 9-1-1 caller . . . should not be accepted until subjected to cross examination.'” The Fifth Circuit reversed; in addition to a ground based on qualfied immunity law, the Court held that under general Rule 56 principles: ”There is no evidence to suggest that the pair was biased, and the district court specifically found that the heirs ‘[did] not offer any evidence to contradict the eyewitnesses’ statements.’ Because their testimony was ‘uncontradicted and unimpeached,’ the district court was required to give it credence. Failure to do so amounted to an inappropriate ‘credibility determination[].'” Orr v. Copeland, No. 16-50023 (Dec. 22, 2016).

Defendants moved for summary judgment, on the ground of qualified immunity, in a case arising from a fatal police shooting. The district court “disregarded the testimony of [Officer] Copeland and two eyewitnesses, finding that because there was ‘no video evidence of the actual shooting[,]’ the ‘testimony of Copeland, the eyewitness, and the 9-1-1 caller . . . should not be accepted until subjected to cross examination.'” The Fifth Circuit reversed; in addition to a ground based on qualfied immunity law, the Court held that under general Rule 56 principles: ”There is no evidence to suggest that the pair was biased, and the district court specifically found that the heirs ‘[did] not offer any evidence to contradict the eyewitnesses’ statements.’ Because their testimony was ‘uncontradicted and unimpeached,’ the district court was required to give it credence. Failure to do so amounted to an inappropriate ‘credibility determination[].'” Orr v. Copeland, No. 16-50023 (Dec. 22, 2016).